Human–AI Learning: Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Learning System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Educational Potential of AI

1.2. Purpose and Structure of This Paper

2. Educational Context

2.1. Context and Rationale

2.2. 21st-Century Graduate Skills and Dispositions

2.3. Competency-Based Education

2.4. Educating the Whole Person

3. Learning with AI

3.1. Socratic Dialogue

3.2. Formative Assessment and Learning Objectives

- •

- Substitution—technology is a direct tool substitute, without requiring any other change to teaching methods and delivery.

- •

- Augmentation—technology is a direct tool substitute, but results in functional improvements.

- •

- Modification—technology enables significant redesign of teaching delivery and learning tasks.

- •

- Redefinition—technology enables the creation of novel teaching delivery and learning tasks that were previously inconceivable.

3.3. AgenticAI and Co-Creation

- a Problem-Based Learning Activity rated at Level 2, involving a small group of medical students with assistance from AI in researching medical symptoms and generating hypotheses for diagnoses;

- an individual project rated at Level 3, in which AI assists an engineering student in the presentation of designs and calculations for a load-bearing beam;

- an individual project rated at Level 4, in which AI works with a mathematics student to research and model the behaviour of advanced hyperbolic functions;

- a workplace simulation rated at Level 5, in which AI works with a small group of students developing an online game in the identification and design of multiple outcomes;

- an online conferencing activity rated at Level 2, in which AI assists business management students in the design and presentation of slideshows to pitch for a contract;

- a face-to-face viva voce examination rated at Level 1, in which an urban design student is questioned on the safety features of a shopping mall.

4. AI-Supported Learning Systems

4.1. Learning Experience Platforms

4.2. Multi-Agent Systems

4.3. Overview of Recent AI in Education Studies

4.4. Ethical Issues and Guidelines

5. Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Co-Created Learning System

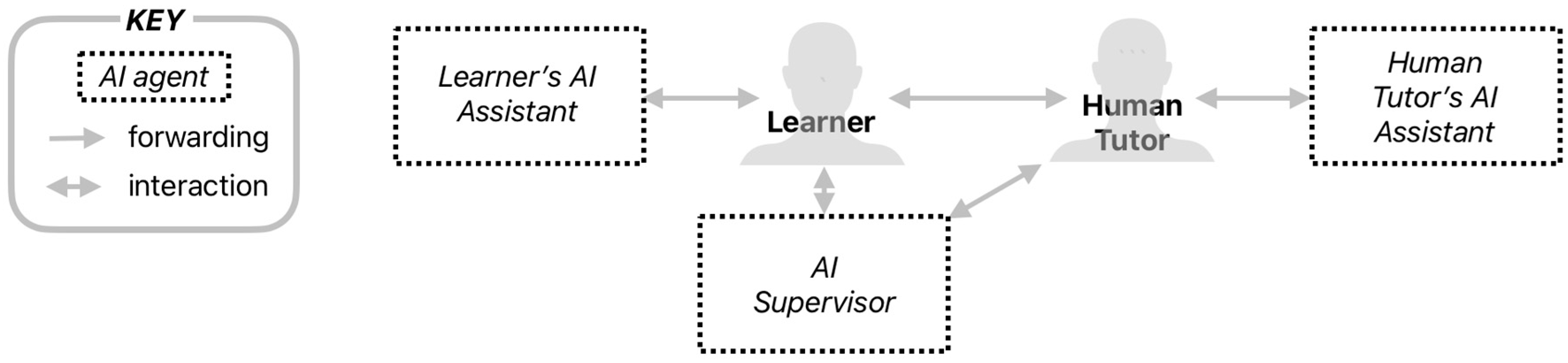

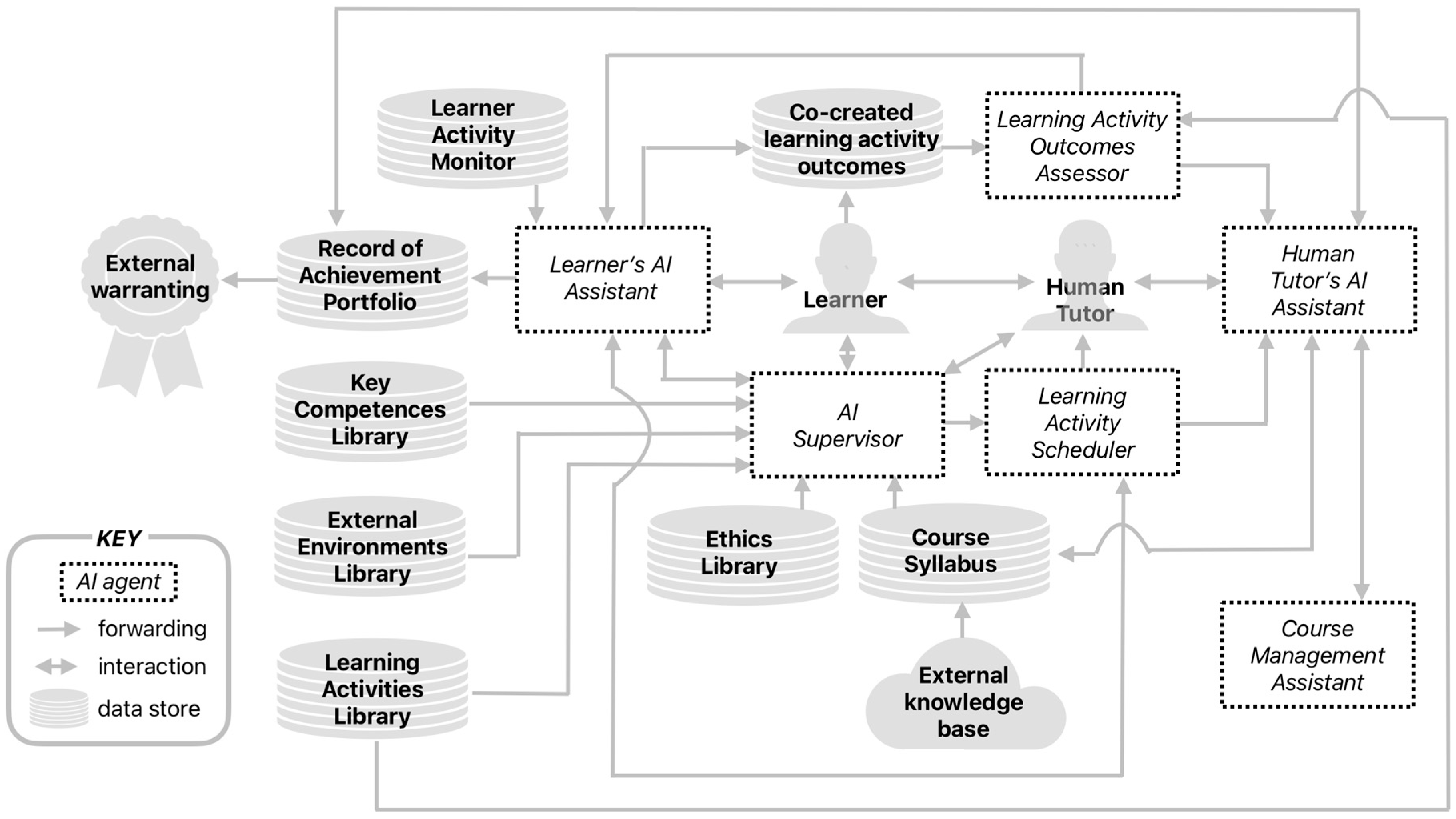

5.1. Principal Agents of the HCLS

5.2. Overview of HCLS Processes

- •

- The AI Supervisor consults the Course Syllabus and relevant libraries to select a learning activity for the Learner. The difficulty level and suitability are determined in consultation with the Learner’s AI Assistant and the details are passed to the Learning Activity Scheduler. This agent specifies a learning activity which is forwarded to the Learner’s AI Assistant and the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant.

- •

- The Learner’s AI Assistant cues the activity with the Learner at an opportune time, supports the Learner in completing the learning activity, and forwards the outcomes to the Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor.

- •

- The Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor evaluates the outcomes against the specification and reports to the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant.

- •

- The Human Tutor’s AI Assistant reports to the Human Tutor and forwards evidence of competence levels to the Learner’s Record of Achievement Portfolio. This is then made available to external systems for academic warranting and awards.

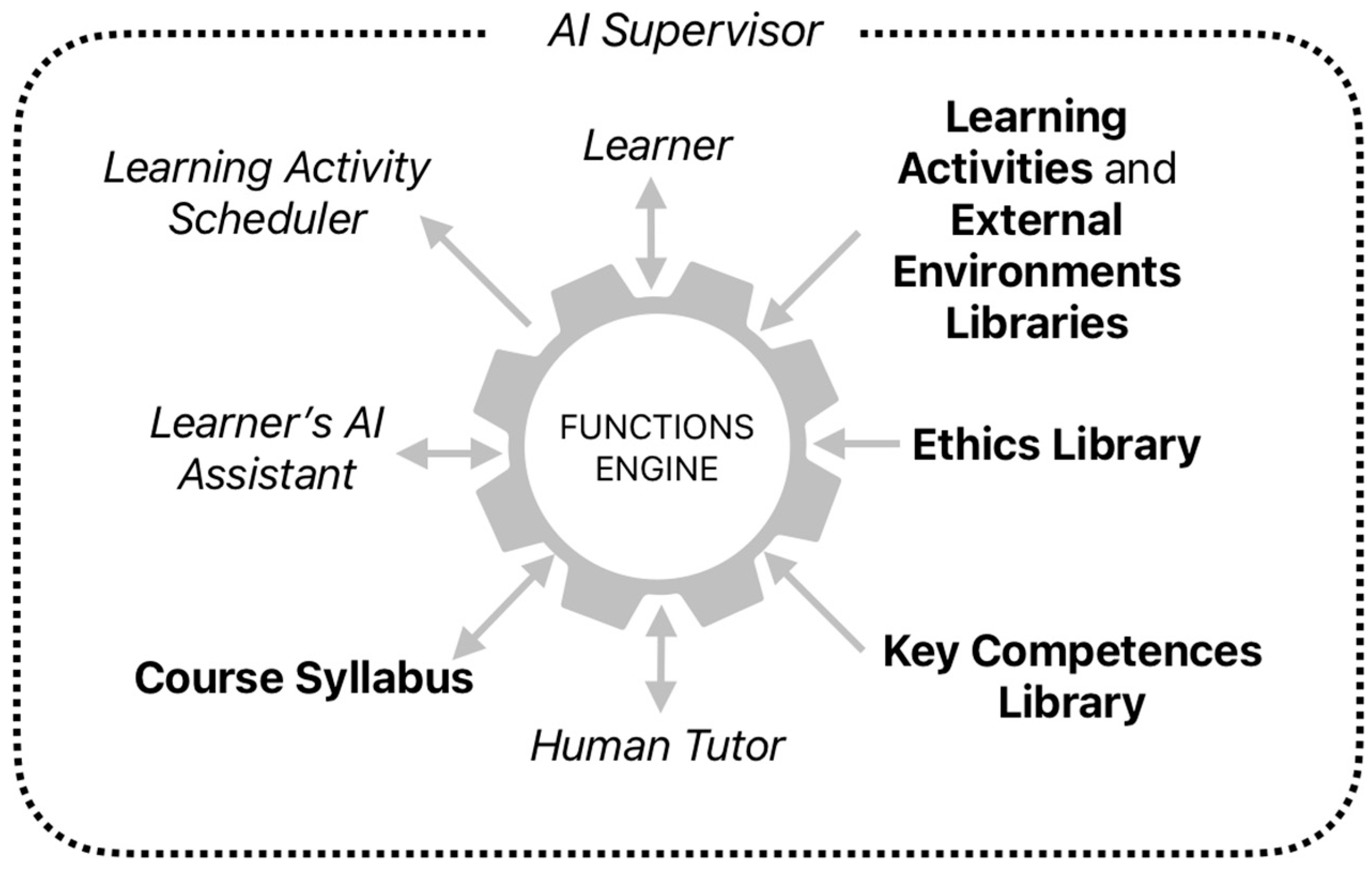

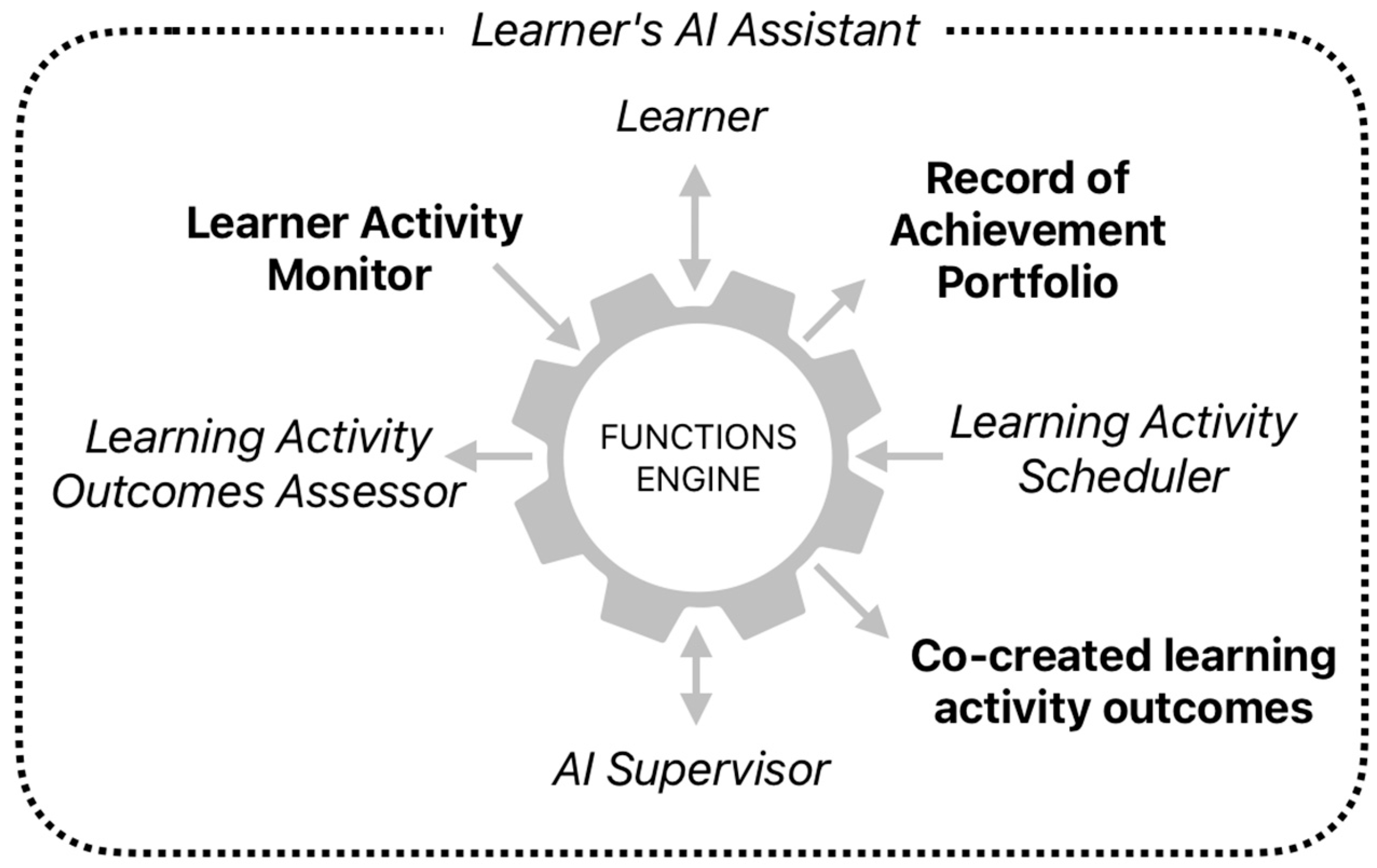

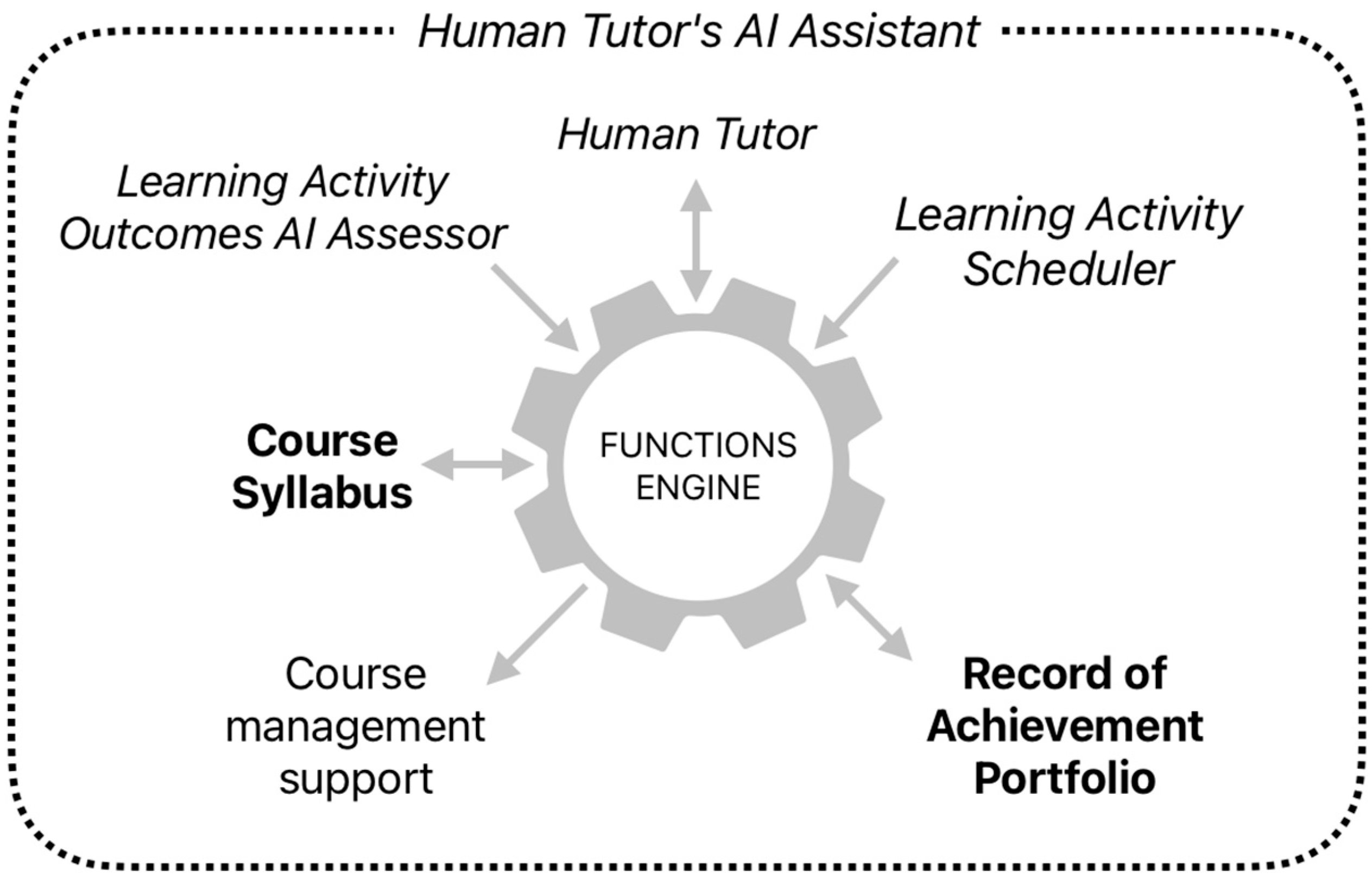

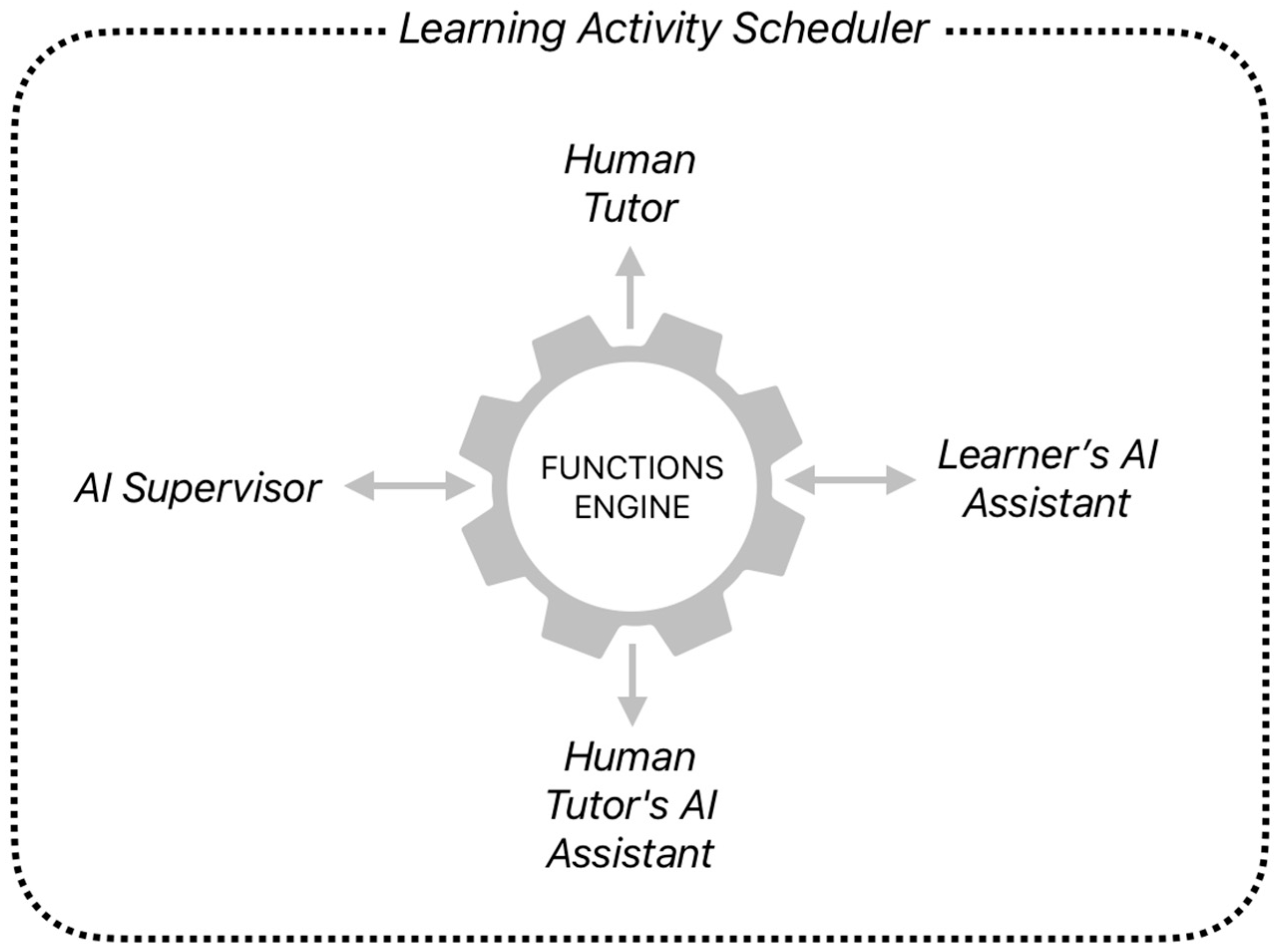

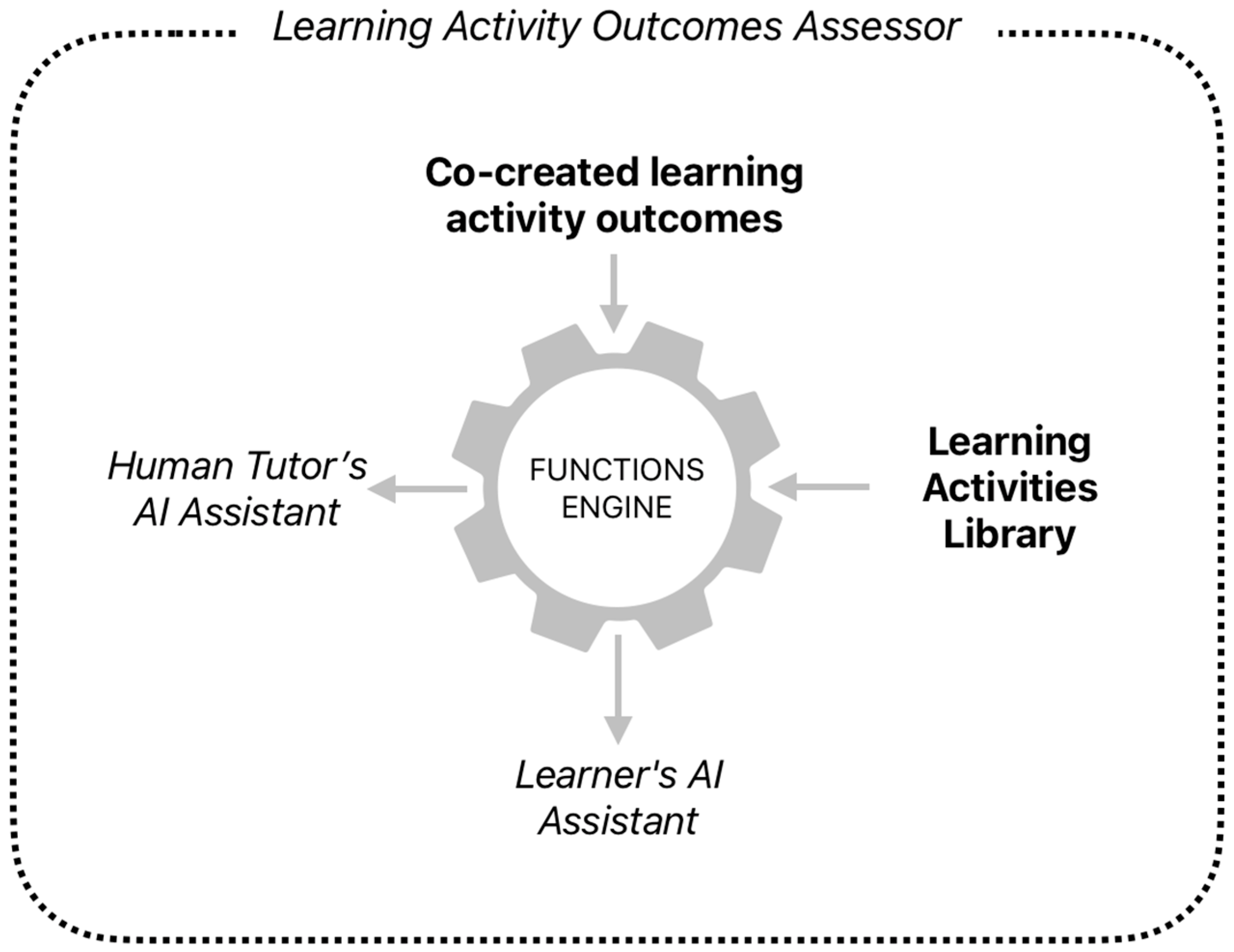

5.3. Functions of AI Agents in the HCLS

5.3.1. Functions of the AI Supervisor

5.3.2. Functions of the Learner’s AI Assistant

5.3.3. Functions of the Human Tutor’s AI Assistant

5.3.4. Functions of the Learning Activity Scheduler

5.3.5. Functions of the Learning Activity Outcomes Assessor

5.4. Feedback Paths Within the HCLS

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Evaluating the HCLS Against Educational and Ethical Criteria

6.2. Evaluating the HCLS Against Criteria for Safe Technical Operation

6.3. Potential Adoption of the HCLS in Higher Education

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niedbał, R.; Sokołowski, A.; Wrzalik, A. Students’ Use of the Artificial Intelligence Language Model in their Learning Process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 225, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, J. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education and Its Implications for Assessment. TechTrends 2024, 68, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.A.; Wittmayer, J. Transforming universities. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.M. The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date. Quant. Financ. 2014, 14, 1701–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. The Fearless Future: 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer; PwC: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/artificial-intelligence/ai-jobs-barometer.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Education. Direct Assessment (Competency-Based) Programs; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/higher-education-laws-and-policy/higher-education-policy/direct-assessment-competency-based-programs (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sturgis, C. Reaching the Tipping Point: Insights on Advancing Competency Education in New England; iNACOL: Vienna, VA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED590523.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kaliisa, R.; Rienties, B.; Mørch, A.; Kluge, A. Social Learning Analytics in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Environments: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies. Comput. Educ. Open 2022, 3, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datnow, A.; Park, V.; Peurach, D.J.; Spillane, J.P. Transforming Education for Holistic Student Development; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/transforming-education-for-holistic-student-development/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- NFER. The Skills Imperative 2035; NFER: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/the-skills-imperative-2035 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Saito, N.; Akiyama, T. On the Education of the Whole Person. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 56, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K. Educating for Wholeness, but Beyond Competences: Challenges to Key-Competences-Based Education in China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynbassarova, D.; Porta, S. Implementing the Socratic Method with AI: Opportunities and Challenges of Integrating ChatGPT into Teaching Pedagogy. 2024. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ab1cf9d86d10bcdec408489c0ae534aa944a65f4 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tapper, T.; Palfreyman, D. The Tutorial System: The Jewel in the Crown. In Oxford, the Collegiate University; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, A. Reviewing the effectiveness of the Oxford tutorial system in teaching an undergraduate qualifying law degree: A discussion of preliminary findings from a pilot study. Law Teach. 2017, 52, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissack, M.; Meagher, B. Responsible Use of Large Language Models: An Analogy with the Oxford Tutorial System. She Ji 2024, 10, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Msafiri, M.M.; Kangwa, D. Exploring the impact of integrating AI tools in higher education using the Zone of Proximal Development. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 7191–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2018, 25, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmigiani, D.; Nicchia, E.; Murgia, E.; Ingersoll, M. Formative assessment in higher education: An exploratory study within programs for professionals in education. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1366215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafa, A.; Lestariningsih, W. Formative Assessment Strategies to Increase Student Participation and Motivation. Proc. Int. Conf. Relig. Sci. Educ. 2025, 4, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sambell, K.; McDowell, L.; Montgomery, C. Assessment for Learning in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, L.H.; Bok, H.G.; de Jong, L.H.; van der Schaaf, M.F.; Kremer, W.D.; van der Vleuten, C.P. A scoping review on the notions of Assessment as Learning (AaL), Assessment for Learning (AfL), and Assessment of Learning (AoL). Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 71, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atjonen, P.; Kontkanen, S.; Ruotsalainen, P.; Pöntinen, S. Pre-Service Teachers as Learners of Formative Assessment in Teaching Practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2024, 47, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckney, P.; Thompson, J.; Vaz-Serra, P. Designing Effective Peer Assessment Processes in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2025, 44, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, B.; Panwar, R.; Chaudhary, S. AI-Driven Learning Analytics for Personalized Feedback and Assessment in Higher Education. In Using Traditional Design Methods to Enhance AI-Driven Decision Making; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarno, S.; Al Azies, H. The Effectiveness of Continuous Formative Assessment in Hybrid Learning Models: An Empirical Analysis in Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Pedagog. Teach. Educ. 2024, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Epp, C.; Chen, F.; Cui, Y. Examining change in students’ self-regulated learning patterns after a formative assessment using process mining techniques. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Weng, X.; Ouyang, F.; Jin, T.; Chiu, T. A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G.; Yankova, T.; Ruseva, M.; Kabaivanov, S. A Framework for Generative AI-Driven Assessment in Higher Education. Information 2025, 16, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideeg, A. Bloom’s Taxonomy, Backward Design, and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development in Crafting Learning Outcomes. Int. J. Linguist. 2016, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, G.; McTighe, J. Understanding by Design; Merrill-Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Puentedura, R. SAMR: Moving from Enhancement to Transformation. 2013. Available online: https://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2013/04/16/SAMRGettingToTransformation.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Sehgal, G. AI Agentic AI in Education: Shaping the Future of Learning; Medium Blog: Gurugram, Haryana, India, 2025; Available online: https://medium.com/accredian/ai-agentic-ai-in-education-shaping-the-future-of-learning-1e46ce9be0c1 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Malik, T.; Shawosh, M.; Albashrawi, M.A.; Jeon, I.; Dutot, V.; Appanderanda, M.; Crick, T.; De’, R.; et al. AI Agents and Agentic Systems: A Multi-Expert Analysis. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2025, 65, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, I. Towards hybrid human-AI learning technologies. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukurova, M. The interplay of learning, analytics and artificial intelligence in education: A vision for hybrid intelligence. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S.; Zhao, G.; Nguyen, A.; Chen, H. Hybrid Intelligence: Human-AI Co-evolution and Learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Furze, L.; Roe, J.; MacVaugh, J. The Artificial Intelligence Assessment Scale (AIAS): A Framework for Ethical Integration of Generative AI in Educational Assessment. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2024, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, P.; Nugroho, S.; Schmidt, C.; Sänger, V. Practical Use of AI-Based Learning Recommendations in Higher Education. In Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning, 14th International Conference. MIS4TEL 2024, Salamanca, Spain, 26–28 June 2024; Herodotou, C., Papavlasopoulou, S., Santos, C., Milrad, M., Otero, N., Vittorini, P., Gennari, R., Di Mascio, T., Temperini, M., De la Prieta, F., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. Artificial Intelligence for Learning: Using AI and Generative AI to Support Learner Development; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Valdiviezo, A.D.; Crawford, M. Fostering Soft-Skills Development through Learning Experience Platforms (LXPs). In Handbook of Teaching with Technology in Management, Leadership, and Business; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, C.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Veith, C.; Dobrea, R.C. Artificial Intelligence and Competency-Based Education: A Bibliometric Analysis. Amfiteatru Econ. 2024, 26, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.M.; Qureshi, A. Impact of technology-based collaborative learning on students’ competency-based education: Insights from the higher education institution of Pakistan. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 2025, 15, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cikmaz, M.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Intelligent Assistant for Personalized and Adaptive Learning in Higher Education. Information 2024, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, N.; Hoon, T. Exploring the Synergy of Learning Experience Platforms (LXP) with Artificial Intelligence for Enhanced Educational Outcomes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation & Entrepreneurship in Computing, Engineering & Science Education; Advances in Computer Science Research; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2024; Volume 117, pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, A.; Beltran-Velez, N.; Chu, Q.; Karlekar, S.; Kossen, J.; Gal, Y.; Cunningham, J.P.; Blei, D. Estimating the hallucination rate of generative AI. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 31154–31201. [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza, U.; Garcia, A.; Lucena, C.; Alencar, P. A generative approach for multi-agent system development. In International Workshop on Software Engineering for Large-Scale Multi-Agent Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.F.T.; Liang, M.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y. OC-HMAS: Dynamic Self-Organization and Self-Correction in Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems Using Multi-Modal Large Models. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 13538–13555. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Ma, Y.; Lang, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhong, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, F. Generative Thinking, Corrective Action: User-Friendly Composed Image Retrieval via Automatic Multi-Agent Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, B.; Buehler, M.J. MechAgents: Large language model multi-agent collaborations can solve mechanics problems, generate new data, and integrate knowledge. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2024, 67, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M.P. Understanding the S-Curve of Ambidextrous Behavior in Learning Emerging Digital Technologies. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2021, 49, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, B. ChatGPT in Computer Science Curriculum Assessment: An analysis of Its Successes and Shortcomings. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on e-Society e-Learning and e-Technologies, Portsmouth, UK, 9–11 June 2023; Volume 2023, pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, M.; Colabianchi, S.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F. Students‘use of large language models in engineering education: A case study on technology acceptance, perceptions, efficacy, and detection chances. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, F.; Levi, D.; Maczo, C.; Simonaityte, A.; Triantafyllidis, S.; Varda, G. Creative Use of OpenAI in Education: Case Studies from Game Development. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, A.; Papadopoulos, P.M.; McKenney, S.; de Jong, T. Investigating the Impact of a Collaborative Conversational Agent on Dialogue Productivity and Knowledge Acquisition. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2025, 35, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, M.; Almaatouq, A.; Malone, T. When combinations of humans and AI are useful: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 8, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovari, A. A systematic review of AI-powered collaborative learning in higher education: Trends and outcomes from the last decade. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Patiño, E.; Marulanda, C. Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Trends, Benefits, and Challenges. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkina, M.; Daniel, S.; Nikolic, S.; Haque, R.; Lyden, S.; Neal, P.; Grundy, S.; Hassan, G.M. Implementing generative AI (GenAI) in higher education: A systematic review of case studies. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Warr, M.; Islam, R. TPACK in the age of ChatGPT and Generative AI. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2023, 39, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, L.; Nie, P.; Yao, Y. Beyond Intentions: A Critical Survey of Misalignment in LLMs. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 85, 249–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, C.; Jeon, G.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H. Automated Audit and Self-Correction Algorithm for Seg-Hallucination Using MeshCNN-Based On-Demand Generative AI. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jedličková, A. Ethical Approaches in Designing Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. AI Soc. 2024, 39, 2201–2214. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose, S. The Next “Next Big Thing”: Agentic AI’s Opportunities and Risks; UC Berkeley Sutardja Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://scet.berkeley.edu/the-next-next-big-thing-agentic-ais-opportunities-and-risks/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, J. Ensuring human oversight in high-performance AI systems: A framework for control and accountability. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 20, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Artificial Intelligence Act). 12 July 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380455 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (UK). Implementing the UK’s AI Regulatory Principles: Guidance for Regulators. 5 February 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/implementing-the-uks-ai-regulatory-principles-initial-guidance-for-regulators (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Tabassi, E. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST Special Publication; AI RMF 1.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/nist.ai.100-1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. In Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Wellbeing with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems, Version 1; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/wp-content/uploads/import/documents/other/ead_v1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- IEEE Standards Association. P7999: Standard for Integrating Organizational Ethics Oversight in Projects and Processes Involving Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://sagroups.ieee.org/7999-series/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Microsoft. Microsoft Responsible AI Standard—General Requirements; Microsoft Corp.: Redmond, WA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://cdn-dynmedia-1.microsoft.com/is/content/microsoftcorp/microsoft/final/en-us/microsoft-brand/documents/Microsoft-Responsible-AI-Standard-General-Requirements.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Google. AI Principles and Google Cloud Responsible AI Guidance. 2018. Available online: https://ai.google/principles/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- OpenAI. Safety & Responsibility; Usage Policies. OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA. Available online: https://openai.com/safety/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence. The Chinese Approach to Artificial Intelligence: An Analysis of Policy, Ethics, and Regulation; BAAI: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, D. Understanding Artificial Intelligence Ethics and Safety: A Guide for the Responsible Design and Implementation of AI Systems in the Public Sector; The Alan Turing Institute: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Designing with AI: A Systematic Literature Review on the Use, Development, and Perception of AI-Enabled UX Design Tools. Adv. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 2025, 3869207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, K.V.; Lovianova, I.V.; Volkov, S.V.; Sitak, I.V.; Chumak, O.O.; Krasnoshchok, A.V.; Bohdanova, N.G.; Semerikov, S.O. UI/UX design of educational on-line courses. CTE Workshop Proc. 2022, 9, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Governors University. Available online: https://www.wgu.edu/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Capella University. FlexPath. Available online: https://www.capella.edu/capella-experience/flexpath/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Purdue Global. ExcelTrack. Available online: https://www.purdueglobal.edu/degree-programs/business/exceltrack-competency-based-mba-degree/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Koh, J.H.L.; Daniel, B.K. Shifting Online during COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Teaching and Learning Strategies and Their Outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fhloinn, E.N.; Fitzmaurice, O. Mathematics Lecturers’ Views on the Student Experience of Emergency Remote Teaching Due to COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadağ, E.; Su, A.; Ergin-Kocaturk, H. Multi-Level Analyses of Distance Education Capacity, Faculty Members’ Adaptation, and Indicators of Student Satisfaction in Higher Education during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | GenAI | AgenticAI |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Acts in response to human input | Acts autonomously in response to learner and environment |

| Workflow | Automates given workflow processes | Optimises and evolves new workflow processes |

| Decision-making | Makes decisions on the basis of predictive learning analytics data | Employs self-learning for proactive decision-making |

| AI Tutor roles | ‘Secretarial support’ and dialogic engagement | Adapting and personalising activities and curriculum for the learner |

| Level 1 | No use of AI |

| Level 2 | AI used for brainstorming, creating structures, and generating ideas |

| Level 3 | AI-assisted editing, improving the quality of student-created work |

| Level 4 | Use of AI to complete certain elements of the task, with students providing a commentary on which elements were involved |

| Level 5 | Full use of AI as ‘co-pilot’ in a collaborative partnership without specification of which elements were wholly AI-generated |

| AgenticAI Support for Individual Working | AgenticAI Support for Team Working |

|---|---|

| Curating student’s study activity with notes, summaries, diary management and links to resources | Curating information and resources, team communications and liaison to support students’ team working. |

| Providing Socratic tutoring and dialogic formative assessment | Providing Socratic tutoring and dialogic formative assessment |

| Checking and improving the quality of student-created work | Identifying and curating team working and improving the quality of collaborative achievements |

| Human–AgenticAI co-creation between student and AI tutor | Supporting peer evaluations of collaborative working; engaging in ‘hybrid human-AI shared regulation in learning’ (HASRL) |

| Activities/Environments | PBL | Projects | Research | Teamwork | Presentations | Viva Voce |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flipped classroom/blended | B Level 3 | |||||

| Individual online | C Level 4 | |||||

| Collaborative online | E Level 2 | |||||

| Workplace/simulation | A Level 2 | D Level 5 | ||||

| Laboratory/workshop/studio | F Level 1 |

| Function | Learning Management Systems | Learning Experience Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Locus of control | Tutor/Administrator control. Cognitivist orientation in focus on content delivery and management. | Learner control. Constructivist orientation in focus on learner experience and engagement. |

| Personalisation | Limited personalisation of content and tasks. | AI-driven personalisation of content and activities, based on user preferences and behaviour. |

| Social and collaborative orientation | Limited social interaction features. | Flexible opportunities for social and collaborative learning. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Williams, P. Human–AI Learning: Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Learning System. Information 2025, 16, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121101

Williams P. Human–AI Learning: Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Learning System. Information. 2025; 16(12):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121101

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilliams, Peter. 2025. "Human–AI Learning: Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Learning System" Information 16, no. 12: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121101

APA StyleWilliams, P. (2025). Human–AI Learning: Architecture of a Human–AgenticAI Learning System. Information, 16(12), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121101