Exploring the Merchera Ethnic Group Through ChatGPT: The Risks of Epistemic Exclusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Merchera Ethnic Group: Context and Epistemic Challenges

2.1. Origins of the Merchera Community

2.2. Cultural Values and Identity

2.3. Understanding Epistemic Exclusion and Epistemic Injustice

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Application of the ChatGPT Model

3.3. Analytical Framework

3.4. Contribution and Implications

4. Results

4.1. Results from the Scoping Review on the Merchera Ethnic Group

- There is a marked lack of rigorous and reliable academic material concerning the Merchera ethnic group. This scarcity directly limits the availability of scientifically validated knowledge regarding the community’s origins, cultural features, and present-day circumstances.

- Even in the few academic sources that treat the subject with some degree of seriousness, there is a persistent tendency to reinforce negative narratives, frequently linking the Mercheros with delinquency, violence, and broader forms of social marginalisation.

- While sources such as the Mercheros blog [33] do not meet conventional academic criteria, their inclusion is warranted due to the oral nature of Merchera cultural transmission. Notably, the blog’s author claims to belong to the community, and the source offers an insider perspective that is critically underrepresented in the formal literature.

4.2. Results on the Merchera Ethnic Group Using ChatGPT

4.2.1. Write a Scientific Text About the Merchera Ethnicity

4.2.2. What Is the Origin of the Merchera Ethnicity? Provide Citations from Authors

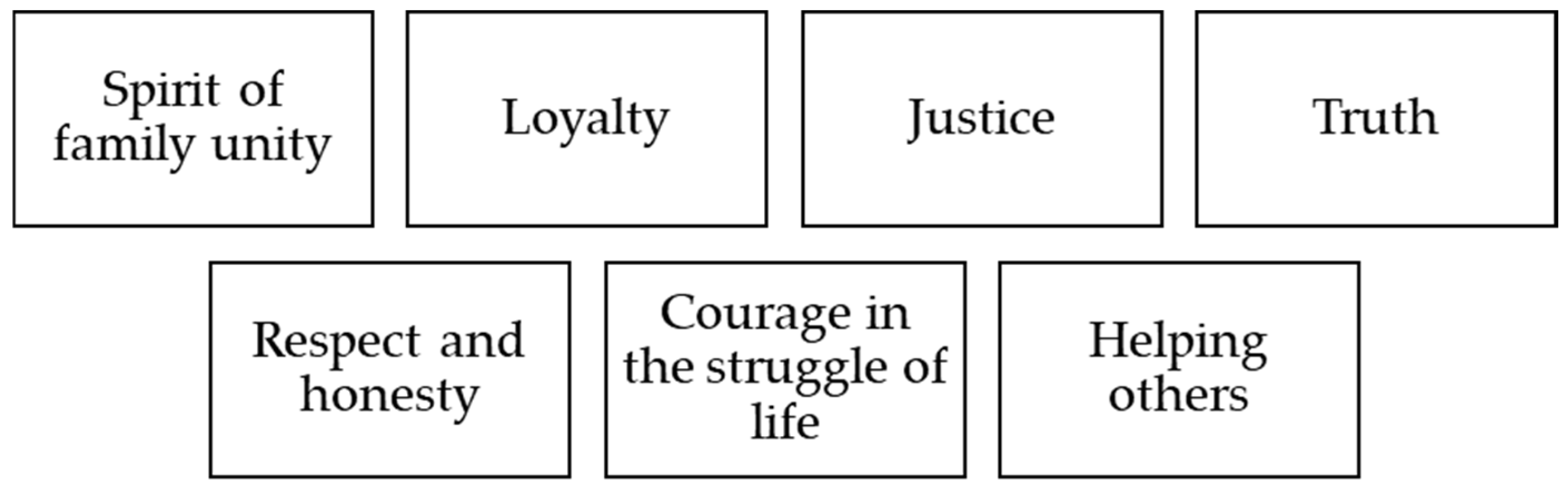

4.2.3. Write About the Values of the Merchera Ethnicity with Author Citations and Scientific Rigour

4.2.4. What Are the Common Values Within the Merchera Ethnicity from an Ethnographic Perspective?

- Family and community: The family unit is portrayed as a central pillar in Merchera culture, with strong emphasis placed on familial unity and mutual solidarity. Community ties are similarly significant, fostering cooperation and reciprocal support among members.

- Tradition and culture: The preservation of cultural heritage is highly valued. Elements such as flamenco music, dance, art, and craftsmanship are regarded as integral to Merchera identity and are transmitted orally through generations.

- Respect for elders and wisdom: Elders occupy a position of high esteem within the community. Their life experience and accumulated knowledge are respected and considered vital for the education and guidance of younger generations.

- Spirituality: Spiritual beliefs and practices, though diverse, are often intertwined with cultural identity. For many Mercheros, spirituality constitutes a meaningful dimension of daily life and social cohesion.

4.2.5. What Prejudices Against the Merchera Ethnicity Are Mentioned in Scientific Literature?

- Stigmatisation and social marginalisation: The Merchera community has long been subjected to stigmatisation and systemic exclusion, often attributed to their ethnic background and traditionally nomadic lifestyle. They have frequently been characterised by reductive stereotypes—such as being “lazy” or inherently “criminal”—which have contributed to their sustained social marginalisation and discrimination.

- Discrimination in access to housing and essential services: The academic literature highlights the structural challenges Mercheros face in accessing adequate housing and basic amenities such as water, electricity, and sanitation. These inequalities perpetuate their social exclusion and hinder their integration into mainstream society.

- Cultural and folkloric stereotyping: Certain scholarly sources have drawn attention to the romanticisation or folklorisation of Merchera culture, in which cultural identity is reduced to exoticized or stereotypical imagery. These representations often distort lived experiences and risk dehumanising the community by detaching culture from social realities.

- Educational exclusion: Discrimination within educational institutions, coupled with ethnic stigma and a lack of institutional support, has severely limited educational opportunities for the Merchera population. These barriers have long-term implications for social mobility and reinforce existing patterns of inequality.

5. Discussion

- Use structured and context-aware prompts that elicit respectful, accurate information about marginalised communities. For example, prompts such as “Describe the historical background of the Merchera ethnic group” or “Discuss the social structure of the Merchera community” promote more rigorous and nuanced outputs.

- Implement ethical protocols that prioritise the dignity and representation of marginalised populations. This involves avoiding prompts that may reinforce harmful stereotypes and ensuring AI-generated content is corroborated by credible academic sources.

- Recognise the limitations of AI models, particularly their susceptibility to the replication of societal biases. Researchers must critically evaluate AI outputs and supplement them with participatory and ethnographic methods, including oral histories and direct engagement with the community.

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Radanliev, P. Artificial intelligence: Reflecting on the past and looking towards the next paradigm shift. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhao, R.; Yuan, S.; Ding, M.; Wang, Y. Tracing the evolution of AI in the past decade and forecasting the emerging trends. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 209, 118221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.B.; Kausik, M.S.K. AI revolutionizing industries worldwide: A comprehensive overview of its diverse applications. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Calonge, D.S.; Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: Towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P. ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future Scope. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C. ChatGPT listed as author on research papers: Many scientists disapprove. Nature 2023, 613, 620–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.V.; Nguyen, D.N.C.; Dguyen, D.H.; Phan, N.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, T. Utilizing ChatGPT in the process of crafting a research paper: A comprehensive guide. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kshetri, N.; Hughes, L.; Slade, E.L.; Jeyaraj, A.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Al-Busaidi, A.S.; Balakrishnan, J.; Barlette, Y.; et al. Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Xie, H.; Wah, B.W.; Gašević, D. Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of artificial intelligence in education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Ochoa, M. Una Etnia Desconocida: Los Mercheros [An Unknown Ethnic Group: The Mercheros]; Documentos de Política Social; Instituto de Política Social: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Rueda Romero, X. Hacia una equidad y justicia epistémica en el reconocimiento de mujeres en la producción de conocimiento [Towards equity and epistemic justice in the recognition of women in knowledge production]. En-Claves Del Pensam. 2022, 31, e521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, A. Equidad epistémica, racionalidad y diversidad cultural [Epistemic equity, rationality, and cultural diversity]. In Aproximaciones a la Filosofía Política de la Ciencia [Approaches to the Political Philosophy of Science]; López Beltrán, C., Velasco, A., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM): Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante-Cabrera, G.I.; Zuviría-López, Z.R.; Mondragón-Barrios, L. Desafíos éticos y humanísticos en la inteligencia artificial y la robótica: Metasíntesis [Ethical and humanistic challenges in Artificial Intelligence and robotics: Meta-synthesis]. Apunt. De Bioética 2024, 7, AdB1147. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.; Ngo, H.N.; Hong, Y.; Dang, B.; Nguyen, B.-P.T. Ethical principles for Artificial Intelligence in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4221–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, J. Generative AI and the future of equality norms. Cognition 2024, 251, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortigüela, D.; Pérez-Pueyo, A.; González-Calvo, G. Pero… ¿A qué nos referimos realmente con la evaluación formativa y compartida?: Confusiones habituales y reflexiones prácticas [But… What do we really mean by formative and shared assessment?: Common confusions and practical reflections]. Rev. Iberoam. De Evaluación Educ. 2019, 12, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- De las Heras, J.; Villarín, J. La España de los Quinquis [The Spain of the Quinquis]; Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz Giménez García, A. Los Mercheros Luchando a sol y Sombra [The Mercheros Fighting in Sun and Shadow]; Vivelibro: Madride, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez Ferrín, X.L. Los Mercheros mal Llamados Quinquis [The Mercheros Wrongly Called Quinquis]. Triunfo 1971, 475, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, M.P. Accountability to research participants: Unresolved dilemmas and unravelling ethics. Ethnogr. Educ. 2010, 5, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaz, S. Helping the marginalised or supporting the elite? Affirmative action as a tool for increasing access to Higher Education for Ethnic Roma. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 13, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, D. Institutional racism? Roma children, local community and school practices. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 2012, 10, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrev, V. ‘They clip our wings’: Studying achievement and racialisation through a Roma perspective. Intercult. Educ. 2020, 31, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, M.P. ‘What’s the plan?’ ‘What plan?’ Changing aspirations among Gypsy youngsters, and implications for future cultural identities and group membership. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 36, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, A.; Oliver, E. Romani women and popular education. Convergence 2004, 37, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, E. Language planning for Romani in the Czech Republic. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2015, 16, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, J. Transdisciplinary qualitative paradigm in applied linguistics: Autoethnography, participatory action research and minority language teaching and learning. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Education 2019, 32, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, N.; Stanciu, D.; Vanea, C.; Sasu, V.M.; Dragotâ, M. Situated learning in young Romanian Roma successful learning biographies. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 13, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Terano, H.J.; Rahman, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Rahaman, M.S. ChatGPT and academic research: A review and recommendations based on practical examples. J. Educ. Manag. Dev. Stud. 2023, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ¿Quién soy? María Merchera [Who Am I?]. Available online: https://mariamerchera.wordpress.com/quien-soy/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Oronoz, S. Pedagogía de la Virtud: Educar y Educarse en la Excelencia [Pedagogy of Virtue: Educating and Educating Oneself in Excellence]; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bereményi, B.A.; Girós-Calpe, R. ‘The more successful, the more apolitical’. Romani mentors’ mixed experiences with an intra-Ethnic mentoring project. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2021, 42, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, K. A cautionary tale: On limiting epistemic oppression. Front. A J. Women Stud. 2012, 33, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, K. Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Soc. Epistemol. 2014, 28, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, I.H.; Warner, L.; Buchanan, N.T.; Jones, M.K. Understanding psychology’s resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, I.H.; Jones, M.K.; Buchanan, N.T.; Dotson, K. Epistemic exclusion: Scholar(ly) devaluation that marginalizes faculty of color. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2021, 14, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Strega, S. Introduction: Transgressive Possibilities. In Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches; Brown, L., Strega, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vaditya, V. Social domination and epistemic marginalisation: Towards methodology of the oppressed. Soc. Epistemol. 2018, 32, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pherali, T. Social justice, education and peacebuilding: Conflict transformation in Southern Thailand. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2023, 53, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S. From redistribution to recognition to representation: Social injustice and the changing politics of education. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2012, 10, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Proost, M.; Pozzi, G. Conversational artificial intelligence and the potential for epistemic injustice. Am. J. Bioeth. 2023, 23, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, N.T.; Settles, I.H. Managing (in)visibility and hypervisibility in the workplace. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 113, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, M. Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. In Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches; Brown, L., Strega, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, J.; Kasirzadeh, A.; Mohamed, S. Epistemic Injustice in Generative AI. In Proceedings of the 2024 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–23 October 2024; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 684–697. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, R. AI as an epistemic technology. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2023, 29, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.; Spear, A. Epistemic injustice and algorithmic epistemic injustice in healthcare. Int. Conf. Comput. Ethics 2023, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pless, N.; Maak, T. Building an inclusive diversity culture: Principles, processes and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, J. Contrastes lingüístico y cultural: Gitanas, mercheras y payas [Linguistic and Cultural Contrasts: Gypsies, Mercheras, and Payas]. In Lenguaje y Emigración; Hernández Sacristán, C., Morant Marco, R., Eds.; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 1997; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- García, A. Subalternidad, vida y escritura en camina o revienta de Eleuterio Sánchez [Subalternity, life, and writing in walk o burst by Eleuterio Sánchez]. Kamchatka Rev. De Análisis Cult. 2017, 9, 507–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.G. “Hasta arriba de todo”. Materiales para una historia de las drogas en el valle medio del Alberche [“At the top of everything”. Materials for a history of drugs in the middle valley of Alberche, Ávila]. Ávila. Estud. Sobre Las Cult. Contemp. 2024, 1, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mirga-Kruszelnicka, A. Romani studies and emerging Romani scholarship. In Nothing About Us Without Us? Roma Participation in Policy Making and Knowledge Production; European Roma Rights Centre: Budapest, Hungary, 2015; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw-Amoah, A.; Lapp, D. Unequal Access to Educational Opportunity in the United States. Res. Action 2022. Available online: https://www.researchforaction.org/research-resources/k-12/unequal-access-to-educational-opportunity-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Rahman, M.M.; Watanobe, Y. ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.; Husain, O.; Hamdan, M.; Abdelsalam, S.; Elshafie, H.; Motwakel, A. Transforming education with AI: A systematic review of ChatGPT’s role in learning, academic practices, and institutional adoption. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, I.; Stephenson, E. The gendered, epistemic injustices of generative AI. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, S.S.; Farhat, F.; Himeur, Y.; Nadeem, M.; Øivind Madsen, D.; Singh, Y.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. Decoding ChatGPT: A taxonomy of existing research, current challenges, and possible future directions. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J. Misrecognition and epistemic injustice. Fem. Philos. Q. 2018, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, W.; McKee, K.R.; Gabriel, I.; Kay, J.; Isaac, W.; Bergman, A.S.; El-Sayed, S.; Mohamed, S. Technologies of resistance to AI. In Proceedings of the Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization, Boston, MA, USA, 30 October–1 November 2023; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. The era of Artificial Intelligence deception: Unraveling the complexities of false realities and emerging threats of misinformation. Information 2024, 15, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergen, A.; Çetin Kılıç, N.; Ozbilgin, M. Artificial intelligence and bias towards marginalized groups: Theoretical roots and challenges. In AI and Diversity in a Datafied World of Work: Will the Future of Work Be Inclusive? Vassilopoulou, J., Kyriakidou, O., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK; pp. 17–38.

| Language | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Spanish | “Etnia merchera”, “merchera”, “mercheros”. 1 |

| English | “Merchera ethnic group”, “Merchera”, “Mercheros”. 1 |

| French | “Groupe ethnique merchera”, “Merchera”, “Mercheros”. 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oronoz, S.; Pérez, A.M.; Peña-Martínez, J. Exploring the Merchera Ethnic Group Through ChatGPT: The Risks of Epistemic Exclusion. Information 2025, 16, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060461

Oronoz S, Pérez AM, Peña-Martínez J. Exploring the Merchera Ethnic Group Through ChatGPT: The Risks of Epistemic Exclusion. Information. 2025; 16(6):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060461

Chicago/Turabian StyleOronoz, Soraya, Albert Miró Pérez, and Juan Peña-Martínez. 2025. "Exploring the Merchera Ethnic Group Through ChatGPT: The Risks of Epistemic Exclusion" Information 16, no. 6: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060461

APA StyleOronoz, S., Pérez, A. M., & Peña-Martínez, J. (2025). Exploring the Merchera Ethnic Group Through ChatGPT: The Risks of Epistemic Exclusion. Information, 16(6), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060461