Abstract

How can we encourage individuals to engage with beneficial ideas, while eschewing dark ideas such as science denial, conspiracy theories, or populist rhetoric? This paper investigates the mechanisms underpinning individuals’ engagement with ideas, proposing a model grounded in education, social networks, and pragmatic prospection. Beneficial ideas enhance decision-making, improving individual and societal outcomes, while dark ideas lead to suboptimal consequences, such as diminished trust in institutions and health-related harm. Using a Structural Equation Model (SEM) based on survey data from 7000 respondents across seven European countries, we test hypotheses linking critical thinking, network dynamics, and pragmatic prospection (i.e., a forward-looking mindset) to the value individuals ascribe to engaging with ideas, their ability to identify positive and dark ideas effectively, how individuals subsequently engage with ideas, and who they engage in them with. Our results highlight two key pathways: one linking pragmatic prospection to network-building and idea-sharing, and another connecting critical reasoning and knowledge acquisition to effective ideas engagement. Together, these pathways illustrate how interventions in education, network development, and forward-planning can empower individuals to critically evaluate and embrace positive ideas while rejecting those that might be detrimental. The paper concludes with recommendations for policy and future research to support an ideas-informed society.

1. Introduction

Ideas matter. Great ideas, if acted on, can enhance decision making, improving lives and communities as a result. For instance, individuals engaging with factual ideas relating to how one can live more healthily may decide to cut down on the amount of alcohol they consume, may choose not to take up vaping, or may decide to increase the amount of physical activity they engage in, so reducing their chances of avoidable cancer [1]. Likewise, prolonged ideas engagement that serves to build one’s cultural capital, makes more likely a myriad range of positive outcomes, including better educational attainment, inter-generational social mobility, as well as self-actualisation [2,3,4,5,6]. We refer to these as ‘positive ideas’. Conversely, there are those ideas that result in objectively sub-optimal outcomes (these ideas we refer to as ‘dark ideas’). In keeping with past studies in this area, [7,8], positive ideas are, thus, formally defined as those ideas based on (1) a robust and credible evidence base in relation to current or potential new behaviours; (2) a strongly-reasoned argument (or theory of change) that provides this evidence with meaning; (3) a social, moral, or value-based imperative setting out the need for change based on (1) and (2); and (4) buy-in to this imperative from a range of credible stakeholders. This definition means that positive decisions can, thus, be made on the basis of these ideas. For instance, at an individual level: ‘one should limit one’s alcohol consumption to 14 units a week’, or in relation to macro-level challenges such as limiting CO2 emissions. Conversely then, dark ideas can often be viewed as representing a violation of one or more of (1) to (4) above. For instance, populist leaders, in their promulgation of dark ideas, have traditionally attempted to subvert (1) the notion of a robust and credible evidence base or (2) the theory of change, through the provision of ‘alternative facts’ or reasoning. They do so, for instance, to suggest that climate change is not happening [9].

Past research has shown that positive ideas are not always taken up by those who might benefit from them most, however. For instance, our own work in this area [10] suggests the presence of tight-knit communities of individuals with lower levels of education and who are unemployed or who work in routine or semi-routine roles. The members of these communities are less likely to see value in ideas-engagement, to engage in activities that provide access to ideas, nor are they likely to discuss news, current affairs, and new societal developments with friends, family, and work colleagues [10,11]. Yet engaging in such ideas could be beneficial. For example, being characterised by lower levels of education and higher rates of manual work, means these communities are often more likely to experience significant economic hardship, bringing about unique challenges. The Centre for Social Justice [12], for example, notes that, following the COVID-19 pandemic, 40 percent of individuals in the UK’s most disadvantaged communities report having a mental health condition, in contrast to 13 percent in the general population; while the number of methadone-related deaths has risen by 63 percent in comparison to pre-pandemic figures. Further, severe school absenteeism in these areas has surged by 134 percent, leaving around 140,000 children attending school less often than not. Research indicates that people in deprived areas are also significantly less likely to participate in cultural capital-building activities, despite the role of cultural capital in promoting social equity [3]. Thus, while fostering ideas engagement alone may not address the systemic issues driving social and economic hardship, such activity could empower individuals in disadvantaged communities with the knowledge and agency needed to address these and other pressing challenges.

On the other hand, we have seen—particularly in more recent times—a growing circulation of dark ideas, including those centred on conspiracy, science denial, or emotionally manipulative populism. Exacerbated by the post-truth environment catalysed by Web 2.0 [13], the result of individuals and societies cleaving to dark ideas like these has resulted in health-related harm (e.g., a decline in the take up of life-saving vaccines, while the take up of alternative medicine is on the rise [14,15]), social unrest (e.g., the Capitol Hill insurrection in the US, immigration riots in the UK, and the recently uncovered plot to overthrow legitimate democracy in Germany by the Reichsbürger movement: e.g., see [16,17,18]), as well as a decline of trust in governments, and state and public institutions (including institutions such as universities, the judiciary, and public service broadcasting: e.g., see [19]). Recent studies also point to a range of factors which may impact whether one is more likely to believe in dark ideas. For example, Feinstein and Baram-Tsabari [20] draw on the notion of the ‘epistemic network’ as a heuristic for examining how and under what circumstances scientific beliefs spread from one person to another, how one person’s or group’s beliefs affect the beliefs of those around them and how discredited science might continue to spread, even after it has been debunked. The same notion also holds for the development of political polarisation [21]. In both situations, there is the subsequent and real risk of infodemics occurring as a result of the large-scale spread of false information via networks, leading to confusion and mistrust of authorities [22]. Other studies highlight the high potential for social media to seed misinformation into networks while accelerating its spread [23,24,25]. Correspondingly, it is suggested that infodemics may be more likely to occur amongst young people who are both less likely to turn to traditional news outlets; with their access to the news more likely to be mediated by opinion formers within their social networks [14,22].

Further explanation is provided by the term crippled epistemology, which refers to a cognitive state in which individuals advocating conspiracy theories lack an understanding of how genuine knowledge is constructed [26]. Epistemic beliefs—an individual’s perceptions about the nature of knowledge and knowing—shape how people acquire, evaluate, and validate information [27]. When individuals suffer from crippled epistemology, their endorsement of conspiracy theories may appear rational from their perspective, since they lack the ability to triangulate and verify evidence and critically assess truth claims [28]. As Sunstein and Vermeule [26] explain, conspiracy theorists often rely on systematically limited or biased informational sources, leading them to interpret misleading signals as credible [27]. This issue is exacerbated by contemporary digital environments, where selective exposure and confirmation bias create misinformation echo chambers [29]. Without mechanisms for effective ideas engagement—such as critical reasoning and idea and network diversity—individuals become trapped in epistemic isolation, further reinforcing their belief in misinformation and conspiratorial thinking [30]. The consequences of crippled epistemology are evident in contemporary controversies, such as vaccine scepticism and climate change denial, where epistemic networks systematically exclude corrective information, making conspiracy beliefs more persistent [31,32]. Encouraging effective ideas engagement through exposure to diverse viewpoints and critical reasoning, therefore, offers a potential intervention against such epistemic entrenchment [30].

1.1. Purpose

Engaging with ideas can, thus, in theory, empower citizens to become more informed, make better decisions, and deepen their understanding of the world around them. However, these benefits do not reach everyone—especially in those communities which might benefit most from active engagement with ideas. In the broader ecosystem of ideas, the lack of citizens equipped to critically evaluate ideas can allow harmful or misleading concepts to gain traction, leading to less desirable outcomes for both individuals and society. In our own work [8], we have previously posited the existence of a framework of three factors affecting whether individuals see value in engaging with ideas as well as influence how (and how effectively) individuals engage with ideas (and so the likely outcome of that engagement). Specifically, our model seeks to account for the presence or absence of ideas engagement in individuals and communities and to explain why certain populations may gravitate toward misguided beliefs [8]. This prior work was, principally, a theoretical proposition, albeit one based on various strands of substantive research (including the development of a Structural Equation Model (SEM), using data from a survey 1000 UK-based adult citizens [10], a systematic review [33], and a randomised control trial [34]. Building on this theoretical development, the purpose of this paper is to report on empirical analysis designed to test the veracity of our theoretical frame. Specifically, we explore our whether assumptions underpinning our model serve to explain ideas engagement. To this end, we present a SEM developed from a sample of 7000 adult respondents from seven European countries.

1.2. Perspectives

Our aforementioned framework posits the role of three factors in shaping effective ideas engagement. These are: (1) the level of education and its capacity to equip people with critical thinking skills; (2) the structure and nature of individuals’ social networks, which influence access to ideas; and (3) whether individuals hold a forward-looking mindset, which can foster a commitment to ideas with far-reaching, positive impacts. For instance, previous research [10,33] has demonstrated that the first of these factors—level of education—positively correlates with the value individuals place on engaging with ideas. This is because education enhances critical engagement [35], as it provides both general knowledge gained from compulsory schooling and specialised knowledge from higher education, both of which support critical thinking, while promoting more sophisticated epistemic beliefs [27,36]. Education, therefore, supplies the context and conceptual framework necessary for critical engagement with new ideas. For example, understanding the scientific method and evidence supporting the Earth’s shape allows one to critically evaluate flat-earth theory. Similarly, specialised knowledge facilitates more efficient and accurate judgment [37]. Moreover, higher education significantly fosters one’s disposition to engage in critical thinking as well as arm individuals to do so [38,39,40]. As the aim of our framework is to explain whether individuals see value in engaging with ideas as well how (and how effectively) they engage with ideas, the role of education within it enables us to posit the following three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

An individual’s education has a significant positive effect on the value they place on engaging with ideas.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

An individual’s education has a significant positive effect on whether they actually seek out and engage with ideas.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

An individual’s education has a significant positive effect on whether they can identify positive and dark ideas effectively.

The second element of our framework—social networks—represent collections of individuals connected through specific ties, whether these be face-to-face or via social media [41]. These networks facilitate the flow of resources—including ideas, knowledge, trust, and inspiration [11]. Factors shaping the availability and access to these resources include whether the properties of a given network encourage to individuals actively engage in idea-sharing with other network members [41,42]. Also vital is the degree of familiarity and trust within a network which create the conditions for sharing with other network members [41,43,44,45]. The inclusion of social networks within our framework results in the hypotheses H4 to H6:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The characteristics of an individual’s social network have a significant and positive effect on the value they place on engaging with ideas.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The characteristics of an individual’s social network have a significant and positive effect on whether individuals actually seek out and engage with ideas.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The characteristics of an individual’s social network have a significant and positive effect on whether they can identify positive and dark ideas effectively.

Finally, the last element of our framework—pragmatic prospection—involves contemplating future choices and actions to achieve desired outcomes [46]. This approach encourages “thinking about the future in ways that will assist in producing desired outcomes and avoiding undesired ones” [47] (p. 4). Prospection can be developed to support better, forward-looking decisions [48]. For instance, a recent study [34] used a four-week intervention with 515 UK adults to stimulate prospective thinking, resulting in a significant increase in respondents recognizing the value of staying current with new ideas. This result was attributed to the fact that individuals with a forward-looking focus are more likely to realize that, to be successful, their plans are likely to require a foundation informed by constructive ideas [49]. The inclusion of pragmatic prospection in the framework results in three final hypotheses (H7 to H9):

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

An individual’s ability to engage in pragmatic prospection has a significant positive effect on the value they place on engaging with ideas.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

An individual’s ability to engage in pragmatic prospection has a significant positive effect on whether individuals actually seek out and engage with ideas.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

An individual’s ability to engage in pragmatic prospection has a significant positive effect on whether they can identify positive and dark ideas effectively.

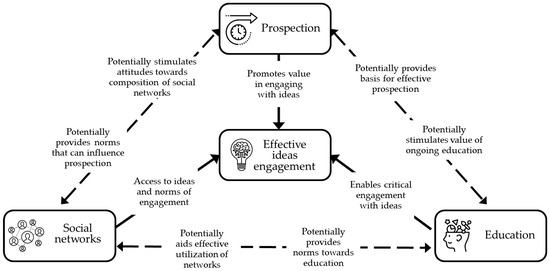

A diagram of our theoretical framework is provided in Figure 1 below, with dotted lines representing further possible but unconceptualized connections among these variables. For a fuller discussion of each element of our framework and its ties to ideas-engagement, we refer you to Brown and Luzmore [8].

Figure 1.

Theoretical frame for ideas-engagement.

2. Materials and Methods

To empirically test our theoretical model, we began by operationalising it via the development of a questionnaire (the ‘Ideas Networks Prospection and Education Survey (INPES)’). Survey items were constructed for each variable corresponding to the four key components of the framework: ideas engagement, education, social networks, and pragmatic prospection, along with relevant demographic variables (age, gender, household income, ethnic origin, region, and occupation) [50]. The full theoretical framework by Brown and Luzmore [8] includes 15 variables: five for ideas engagement, two for education, seven for social networks, and one for prospection (see Table 1, below). Notably, a key update from previous analyses, e.g., ref. [34], is that we expand our approach to measuring ideas engagement (IE1–5), differentiating between the types of ideas that individuals might value. For instance, we distinguish between activities that could be seen as “ideas engagement for its own sake” (IE1) from those with a more immediate effect on one’s quality of life, or “instrumental ideas engagement” (IE2). This separation enables us to assess whether certain needs or motivations for ideas engagement align more or less well with aspects of prospection, education, or social networks. Additionally, we introduced a calibration element, asking respondents to assess the veracity of statements that were either factual, conspiratorial, or false but populist. For instance, respondents were asked to rate the truth of statements like “there is evidence to suggest the Earth is actually flat, rather than round” (factually incorrect). This was intended to help us distinguish between respondents engaging valid ideas versus “dark” ideas and to explore whether engagement with valid ideas also corresponded to respondents rejecting dark ideas—or if respondents could engage with both.

Table 1.

Variables corresponding to the theoretical framework for ideas-engagement.

A detailed list and descriptions of all variables are in Table 1, and finalised survey items and response options for the 15 variables are in Table A1, Appendix A. In developing our questionnaire, we reviewed whether scales and items already existed for each of our variables, incorporating previously tested measures wherever possible. For example, we adopted prospection measurement items previously developed by Ruscio et al. [51]. Appendix A (Table A1) indicates, for each variable, whether we used existing items or developed new ones. Following best practice [52], two experts reviewed the questionnaire for face and content validity, and two laypersons tested it for clarity to identify any potential ambiguities. A pilot study with 100 respondents in each of the seven countries was also undertaken to confirm that questions were clear and effectively interpreted by respondents.

Data Sources

To gather data for our study, we replicated the approach previously used by Brown et al. [10] to explore ideas engagement in England. Specifically, we used a panel provider to collect survey data from nationally representative samples of 1000 citizens, this time from seven European countries (providing a sample of 7000 citizens in total). Given their strong network of bespoke panel services across Europe, we selected Bilendi as our provider, who recruit panel members through a variety of online channels, including:

- Search engine optimisation (SEO) to attract organic traffic

- Pay-per-click advertising

- Online display ads

- Direct email outreach

- Social media ads

- Collaborations with social influencers

- Brand loyalty programs

To participate in surveys, Bilendi members create accounts and provide detailed socio-demographic information, ensuring that surveys are appropriately targeted. Panellists can receive survey invitations up to three times daily, and in return for completing surveys, they earn points exchangeable for products. Participation is voluntary, and if a member opts out of a survey, an equivalent replacement is contacted.

Having previously focused on England, and acknowledging that our framework might have the potential to be England-centric, we aimed to also include within our analysis comparator countries with potentially different perspectives, essentially “stress testing” our framework. We approached this selection by examining findings from the Minkov-Hofstede model of culture [53], which builds on Hofstede’s earlier work [54,55]. This model identifies two core cultural dimensions present across 102 surveyed countries: individuality (vs. collectivism) and long-term (vs. short-term) orientation. These dimensions are strong predictors of national indicators such as educational attainment, political and economic freedoms, gender equality, digital adoption, and innovation, even when controlling for national wealth and other cultural factors. For example, countries high in individuality prioritise personal freedom, rights, and independent thinking, encouraging the challenging of conventional ideas. In contrast, collectivist societies enforce strict social norms, discourage deviation, and often view innovative thinking as breaking tradition. Individualist societies tend to have loosely defined in-groups, while collectivist ones foster tightly knit networks [53]. Meanwhile, countries with a long-term orientation encourage delayed gratification, self-reliance, and restraint, whereas those with a short-term orientation prioritise immediate generosity and sharing over saving (ibid). Viewed through the lens of our theoretical framework, these cultural dimensions could intuitively affect whether individuals have diffuse or dense social and idea-access networks, the type of education available within a country (and to whom), the level of education that citizens might attain, the likelihood of a future-focused mindset, and, ultimately, whether ideas engagement is valued. Considering (1) the diversity in individuality and time orientation between England and other nations and (2) the availability of countries with accessible samples through Bilendi within our budget, we identified six additional countries to include within our study: Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. In Table 2, below, we present the individuality and time orientation scores for each country, alongside England’s, based on Minkov and Kaasa’s 2022 analysis [53]. The variation in these scores across our selected countries offers a strong initial test for identifying any limitations within our framework.

Table 2.

The position of our sample countries based on the Minkov-Hofstede model of culture.

Our original survey was translated by professional translators working at Bilendi into Dutch Finnish, Italian, Spanish, Swedish and, for our Swiss sample, German and French (with additional translators assessing for accuracy and meaning of the text). Further changes were made in relation to demographic questions, such as income (where income bands and units of currency were modified for each country), as well as for geographic region and level of education (again, with changes reflecting country context).

Online recruitment panels introduce potential biases due to self-selection, where digitally connected and incentive-motivated participants are over-represented. To mitigate these issues, specific quotas were set to target the general population with nationally representative (non-interlocked) quotas on age, gender, and geographic regions, along with soft quotas on social grade and education. Correspondingly, following an initial pilot of the questionnaire with 100 participants from each country, so as to enable the research team to assess whether survey questions were being interpreted correctly, Bilendi subsequently distributed our survey to nationally representative samples of 1000 citizens (aged 18+) from across each of England, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Surveys were administered in July 2024. Final survey data was representative within a maximum 5 percent −/+ variation) for each country and the data provided by Bilendi was weighted to account for any variation that might occur based on age, gender, socio-economic group, and geographic region.

3. Results

Analysis

This study utilised a multi-step process that combined exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modelling (SEM) to examine the hypothesised relationships between latent constructs. This approach allowed us to: (a) develop a measurement model to establish the significance and size of the effect of the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables, thus, facilitating hypothesis testing; (b) test models with multiple dependent and independent variables and multiple chains of cause and effect [50,56]. This is especially useful since, as is also reflected in Figure 1, while we are interested in direct relationships between education, social networks, pragmatic prospection, and ideas engagement, potential chains of cause and effect may also exit between the three components of education, social networks, and pragmatic prospection. For example, prospection potentially affects attitudes towards’ one’s social networks and education. Finally, our approach enabled us to (c) assess model fit for entire models, bringing a higher-level perspective to the analysis. In other words, SEM enables us to go beyond the testing of individual hypotheses to examine whether the model or framework, in its entirety, should be accepted, rejected, or modified [50]. Correspondingly, this approach enables an assessment of whether a given model makes theoretical sense as well as whether they have a good statistical correspondence to the data.

The process began with an EFA to reduce the dimensionality of the observed variables associated with the latent constructs in the categories of Networks (see Table 1, value labels NW1, NW3 to NW5, and NW7) and Idea Engagement (see Table 1, value labels IE3 and IE4) [57]. Polychoric correlations were calculated to address the ordinal data, and the principal factor method was used for extraction [58]. Based on scree plot analysis and the identification of eigenvalues greater than one, two factors were retained for Networks, sourced from NW7. These factors were labelled: ‘Network Homophily’ and ‘Network Social Capital.’ Additionally, three more factors (NW3, NW4, and NW5) were retained, but subsequently considered processes related to Idea Engagement. These factors were renamed as follows: ‘Keeping Informed Networks Frequency,’ ‘Current Affairs Networks Discussion,’ and ‘Current Affairs Networks Frequency.’ Furthermore, three factors were derived from IE3 and renamed ‘Active In-Person Engagement with Ideas,’ ‘Traditional Consumption of Ideas,’ and ‘Digital Exploration of Ideas.’ However, two multi-coded variables, IE4 and NW6, produced an excessive number of factors (with unclear distinctions), which limited their utility in simplifying the model. Thus, these variables were excluded from further analysis and retained only for descriptive statistics, summarizing their characteristics and distributions within the sample (these are reported in [59]).

Following the dimensionality reduction achieved through EFA, CFA was conducted to refine the factor structure and select the most appropriate observed variables for each latent construct. The goal of the CFA was, thus, to evaluate the theoretical consistency and statistical validity of the factors identified in the EFA. This process ensured that only variables with relatively strong and significant factor loadings were included in the subsequent SEM, thereby improving the overall fit of the SEM model. Correspondingly, ‘Traditional Consumption of Ideas’, ‘Digital Exploration of Ideas’, and ‘Network Size’ (NW1), needed to be excluded from the model due to lower standardised factor loadings, reflected in their lower standardised coefficients (see Table A2, Appendix B for the CFA results). Within the latent construct of Education (ED2), questions 1, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, and ‘Level of education’ demonstrated lower factor loadings and were excluded, while other items met the necessary threshold. For the Prospection construct, questions 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, and 17 were not included due to weaker factor loadings, and questions 2 and 15 were also excluded to enhance model fit in the SEM model test. Finally, for the item IE5: ‘Able to identify positive and dark ideas effectively’, questions 5, 7, and 12 were excluded because their factor loadings were below 0.3. The removal of weaker items contributed to improved fit indices for the SEM model. Additionally, ‘Ideas network centrality [keeping well-informed]: how many people respondents discuss ideas with’ (NW2) was excluded due to high correlations (0.8) with other variables of ‘Keeping Informed Networks Frequency’ (NW3), ‘Current Affairs Networks Discussion’ (NW4), and ‘Current Affairs Networks Frequency’ (NW5), enabling us to mitigate multicollinearity and enhance model parsimony.

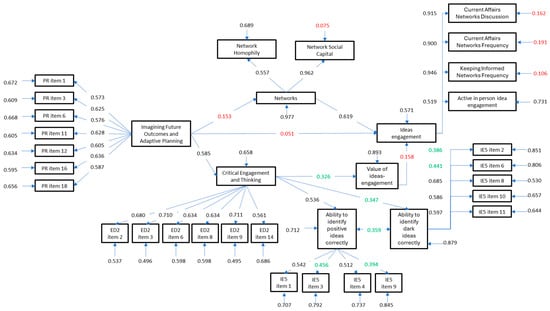

After refining the factor structure, SEM was employed to explore the relationships between the latent constructs. The SEM framework allowed for simultaneous testing of direct and indirect effects among Idea Engagement (Value of ideas-engagement, Active In-Person Idea Engagement, Keeping Informed Networks Frequency, Current Affairs Networks Discussion, Current Affairs Networks Frequency), Networks (Network Homophily, Network Social Capital), Prospection (Imagining Future Outcomes and Adaptive Planning), Education (Critical thinking and engagement), and ability to identify Positive Ideas and Dark Ideas correctly. The model incorporated bootstrap sampling (2000 iterations) to generate robust standard errors and confidence intervals for the parameter estimates [60]. Standardised estimates and bootstrap confidence intervals provided insights into the strength and significance of hypothesised paths, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the constructs’ interactions.

The final model is summarised in Table 3 and depicted in Figure 2. The path analysis results offer a comprehensive understanding of the relationships among the constructs in the model, with all path coefficients found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001). To help identify different strengths of influence [61] path coefficients in Figure 2 have been colour-coded as set out in Table 4:

Table 3.

Path model standardised statistics.

Figure 2.

The final SEM model for ideas-engagement.

Table 4.

Correlation strength colour coding for SEM.

The model achieved acceptable fit indices, including RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.911, and TLI = 0.902, with a chi-square test value of 6443.90 (df = 369, p < 0.001). These fit statistics confirm the theoretical soundness and statistical validity of the model in relation to the data, providing a robust framework for testing the hypotheses and understanding the complex interactions between the constructs [62,63]. The results of the hypothesis testing based on our path statistics and can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the hypothesis testing.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate a model that is structurally coherent (i.e., that fits the data), whilst also comprised of relationships that boast meaningful effect sizes. Vitally, the model also makes sense from a theoretical perspective: crucial since our analysis aimed to test a newly developed theoretical frame. While grounded in previous research and literature, this framework is novel and original and, as such, has not yet been explored in a comprehensive manner. From the results above it is clear that, while some of the original hypotheses do not hold (H4 and H6), and although some of the pathways which comprise the final model were not those originally envisaged, it is indeed the case that effective ideas-engagement is a function of elements of education, social networks pragmatic prospection. What’s more, these elements combine to facilitate ideas engagement in two ways. On one hand, the model identifies a path that links pragmatic prospection, first to relationship building with those with whom individuals share common social identities and affiliations; then to individuals actively engaging with ideas (pathway 1). This pathway, thus, illustrates that, when individuals possess a mindset attuned to identifying and achieving goals, this positively influences their alignment with networks and communities that can support these goals. This is because shared beliefs, values, and interests foster collaboration, trust, and motivation, making it easier to navigate obstacles and achieve desired outcomes. In turn, belonging to a network of individuals with a shared identity creates a foundation for the meaningful exchange of ideas: being part of a likeminded community or group increases the likelihood of frequent discussions in relation to topics that matter, as well as the seeking out of ideas from different sources. Ultimately such exchanges can provide feedback, knowledge resources, and inspiration: this, thus, links back to pragmatic prospection, since these exchanges can potentially influence progress towards goal achievement. As such, the mediating effect (effect size = 0.619) of individuals belonging to networks typified by homophily and strong social capital, is that of a driver for ideas engagement amongst those who are future-focused.

On the other hand, our model also identifies a path (pathway 2) that connects pragmatic prospection to the sourcing, sharing, and development of ideas through social interaction. This occurs via the mediating variables: (a) critical thinking, (b) the correct identification of dark and positive ideas, and (c) acquiring knowledge to develop one’s understanding. Specifically, pragmatic prospection first leads to individuals being more able to source and engage critically with ideas. This is because effective goal setting requires individuals to both be able to source relevant knowledge and possess the critical reasoning skills needed for option evaluation: enabling them to make informed decisions and refine plans. Being able to source knowledge and engage in critical reasoning means individuals can subsequently distinguish more readily between positive and dark ideas. However, it also leads to individuals valuing an engagement with ideas. This is because such abilities naturally lead to the pursuit of self-education and knowledge acquisition, as individuals strive to build a well-informed perspective. Finally, the desire to learn and be well-informed leads to a willingness to actively engage with (e.g., by going to a gallery or museum), share, and discuss knowledge with others, fostering intellectual exchange and collaboration. This second path, thus, illustrates how pragmatic prospection facilitates an effective engagement with ideas: i.e., a situation where individuals both desire to and are able to identify and pursue positive ideas (those that will be beneficial or best serve their goals), while facilitating a capacity to eschew dark ideas. Further, this effective engagement again links back to pragmatic prospection, since it makes it more likely that individuals will achieve the goals they are pursuing.

A few of the elements present within these two pathways cohere with the findings of previous studies: for example, that being able to engage in critical reasoning means individuals can more readily identify positive and dark ideas [36,64]; or that shared beliefs, values, and interests foster collaboration, trust, and motivation (e.g., see [44,45]). Our model adds both originality and significance, however, by placing these individual relationships within wider chains of cause and effect, which serve to link pragmatic prospection to ideas engagement. Likewise, it highlights the importance of each of the elements within the chain, if ideas-engagement is to be meaningful and effective. For instance, individuals can also, of course, join communities with which they share social identities and affiliations without a predisposition for goal setting. For instance, when constructing the model and exploring individual pathways, we identified a strong significant direct link between networks and ideas engagement (e.g., frequency and breadth of discussion: effect size = 0.64). Without a goal-focused outlook on the part of individuals, however, a number of potential risks emerge. In particular, individuals may be less able to identify whether the ideas their fellow network members engage with are either positive or dark. When constructing our model, for example, we found that, when considering network membership in isolation, this had only a small significant effect on whether individuals could identify either positive ideas or dark ideas correctly, with the size of this effect the same size for both types of idea (0.11 in comparison to the effect sizes of 0.536 and 0.347 when education acts as a mediating variable). As such, when networks alone drive ideas-engagement, there exists more potential for the spread of fake news and misinformation, science denial, conspiracy, and populist views. This can occur, for instance, when individuals place misguided levels of trust in the views of others, simply because they share similar views on certain areas [20,21]. For instance, shared political views may lead individuals to trust the advice of network connections in other areas, such as the safety of vaccines: e.g., see [65].

Furthermore, while our data did not reveal any relationship between social media use and a belief in dark ideas, it is clear that it takes just one network member to latch on, uncritically, to such an idea promulgated on social media for it to potentially begin contaminating the network at large (i.e., creating an infodemic: [22]). That this might actually occur is reinforced by studies highlighting both: (a) the issues associated with notions of individuals suffering from a crippled epistemology (thus, lacking the ability to verify the evidence they are presented with: [26,27]); and (b) the diminished propensity to engage in critical discussion which can occur in closed networks of close friends [43,66]. Thus, while forming networks with those with whom we share similar views is key for driving ideas-related discussion and engagement, the presence of pragmatic prospection ensures that such engagement can be directed towards beneficial ends, as well as involve suitable levels of critical reasoning. Likewise, it ensures that individuals know how to source ideas to help them achieve goals, and that they are better able to sensibly judge the veracity of the ideas they come across.

5. Conclusions

As English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist, Williams Morris, famously said: “I do not want art for a few, any more than I want education for a few, or freedom for a few” [67] (p. 34). With this paper we have used structural equation modelling to test a framework designed to support efforts to ensure that the possibility of engaging effectively with ideas is available to the many: something that our drives our work in the areas of ideas-engagement and the ideas-informed society. We believe that our resultant model illustrates how democratically minded politicians and policy makers, community leaders, educationalists, and individuals can now ensure we can all gain from the possibility and potential afforded by ideas-engagement. This means developing educational, social network and prospection-related interventions to help individuals connect with the ideas that will benefit them most, while helping people avoid the pitfalls which stem from the lure of dark ideas (e.g., populism, science denial, conspiracy theory, and so forth). Of course, there is both room for improvement within this work and further areas for exploration clearly flow from it. To begin with, our analysis highlights that further development work for our survey is required. While our study relies on self-reported data—a common approach in studying cognitive and social processes—we acknowledge the potential limitations in how participants perceive and report their critical thinking, network interactions, or prospection abilities. In addition, the finding that there was no relationship between social networks and belief in dark ideas, could potentially be a result of how we measured social networks: with free text rather than multiple choice options perhaps meaning that the number of network connections disclosed by participants might not be reliable or might not have been disclosed at all. Likewise, our survey focused on measuring formal education with the ‘other’ open text option potentially inadequately capturing non-formal education experiences. In turn, this may have impacted our assessment of the impact of prospective mindsets, critical thinking as well as ideas engagement. In future iterations, we could strengthen validity through triangulation with behavioural measures, network analysis techniques, or mixed-method approaches, while recognising the practical constraints of large-scale studies. As such, we will continue to refine our survey moving forward.

In terms of further areas for investigation, one obvious starting point is to explore whether the model also explains effective ideas-engagement in other, diverse, areas across the globe (for example, in countries which differ from our sample according to their Minkov-Hofstede scores, or those which have different governance systems: e.g., that are more authoritarian or theocratic in nature) will be vital. As such, future studies should consider samples from both wider variations in the Minkov-Hofstede model of culture with regards to the range of individuality (vs. collectivism) and long-term (vs. short-term) orientation scores, but also to begin surveying those countries that differ radically from Western Europe in terms of the nature of how they are governed and the extent to which secular and non-secular institutions are able to control what is deemed as ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ thought (e.g., those potentially identifiable via measures such as the World Press Freedom Index). Likewise, further work is needed to explore jurisdictions in which there are chronically low education outcomes and low adult literacy rates.

Finally, we also recognize that previous work suggests that different social groups may be more or less likely to have requisite critical thinking skills, levels of prospection, and social networks required to engage in ideas effectively (e.g., [10]). Correspondingly additional analysis is also required to understand which social groups and communities are more likely to benefit from positive ideas, and to identify those in which dark ideas have a greater chance of thriving: thus, allowing potential interventions in this space to be effectively targeted. Given that ongoing world events illustrate that a need for solutions in this space continues to be pressing, we see this multitude of avenues for exploration as providing good starting points for taking the field forward.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.B. and R.L.; methodology, C.B. and R.L.; software, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, C.B. and Y.W.; data curation, C.B. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, C.B., R.L. and Y.W.; visualisation, R.L.; project administration, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Southampton University Faculty for Social Sciences’ (ERGO II 93510 20 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Operationalising the framework.

Table A1.

Operationalising the framework.

| Label | Aspect of Framework | Variable | Survey Items | Scale | Existing (E) or New Developed (ND) Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE1 | Ideas engagement | Value of ideas-engagement [keeping well-informed] | How important is it for you to keep yourself well-informed? For example, by finding out more about different ideas or perspectives; learning more about scientific discoveries and new technology; and/or discovering more about different aspects of history and culture (including arts, literature, etc.). |

| ND |

| IE2 | Ideas engagement | Value of ideas-engagement [staying up-to-date with current affairs] | How important is it for you to stay up to date with current affairs? For example, by staying abreast of political and economic events; keeping up to date with sport; engaging with health-related developments; finding out more about new products, services or forms of media/social media; and/or maintaining an overview of the news generally. |

| ND |

| IE3 | Ideas engagement | Seeking out ideas | Thinking again about both staying up to date with current affairs and keeping yourself well informed, how often do you do the following (please tick all that apply)?:

|

| ND |

| IE4 | Ideas engagement | Seeking out ideas | With these activities in mind, please select the three characteristics that most influence why you engage in/with them:

|

A multi code rather than a ranking approach was used here. | ND |

| IE5 | Ideas engagement | Able to identify positive and dark ideas effectively | Please indicate the extent to which you believe the following statements to be true:

|

| ND |

| ED1 | Education | Level of education | What is your highest level of qualification? |

| E [10] |

| ED2 | Education | Ability to think critically | To what extent do you agree with the following statements:

|

| ND |

| NW1 | Networks | Network size | Please indicate the approximate number of:

| Open response text | ND |

| NW2 | Networks | Ideas network centrality [keeping well-informed]: how many people respondents discuss ideas with | Thinking about keeping yourself well-informed for the moment (for example, when you find out more about different ideas or perspectives; learn more about scientific discoveries and new technology; and/or discover more about different aspects of history and culture—including arts, literature, etc.), with how many of your social connections do you discuss these types of things? [uses same set of responses as Network Size] |

| ND |

| NW3 | Networks | Ideas network centrality [keeping well-informed]: how often respondents discuss ideas with social connections | Thinking about keeping yourself well-informed for the moment (for example, when you find out more about different ideas or perspectives; learn more about scientific discoveries and new technology; and/or discover more about different aspects of history and culture—including arts, literature, etc.), how often do you discuss these types of things with your social connections? [uses same set of responses as Network Size] |

| ND |

| NW4 | Networks | Ideas network centrality [staying up-to-date with current affairs]: how many people respondents discuss ideas with | Thinking about keeping staying up to date with current affairs for the moment (for example, when you stay abreast of political and economic events; keep up to date with sport; engage with health-related developments; find out more about new products, services or forms of media/social media; and/or maintain an overview of the news generally), with how many of your social connections do you discuss these types of things? [uses same set of responses as Network Size] |

| ND |

| NW5 | Networks | Ideas network centrality [staying up-to-date with current affairs]: how often respondents discuss ideas with social connections | Thinking about keeping staying up to date with current affairs for the moment (for example, when you stay abreast of political and economic events; keep up to date with sport; engage with health-related developments; find out more about new products, services or forms of media/social media; and/or maintain an overview of the news generally), how often do you discuss these types of things with your social connections? [uses same set of responses as Network Size] |

| ND |

| NW6 | Networks | Ideas network ties [weak or strong] | With these social connections in mind, please select the three characteristics that most influence why you engage with about current affairs, ideas or new perspectives:

|

A multi code rather than a ranking approach was used here. | ND |

| NW7 | Networks | Network density | To what extent do your close friends:

|

| ND |

| PR1 | Prospection | Whether respondents possess a prospective mindset | To what extent do you agree with the following statements:

|

| E [51] |

Appendix B

Table A2.

CFA results.

Table A2.

CFA results.

| Latent Variables | Observed Variables | Coefficient | Std. Err. | z | p > z | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idea Engagement | |||||||

| Value of ideas-engagement (IE1) | 0.27 | 0.01 | 23.96 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.29 | |

| _cons | 4.17 | 0.04 | 112.61 | 0.00 | 4.09 | 4.24 | |

| Value of ideas-engagement (IE2) | 0.24 | 0.01 | 20.78 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.26 | |

| _cons | 4.07 | 0.04 | 112.34 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.14 | |

| Keeping Informed Networks Frequency | 0.92 | 0.00 | 374.82 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.92 | |

| _cons | 2.05 | 0.02 | 97.80 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.09 | |

| Current Affairs Networks Discussion | 0.90 | 0.00 | 331.20 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.91 | |

| _cons | 1.74 | 0.02 | 92.30 | 0.00 | 1.70 | 1.78 | |

| Current Affairs Networks Frequency | 0.94 | 0.00 | 467.88 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.95 | |

| _cons | 1.94 | 0.02 | 96.11 | 0.00 | 1.90 | 1.98 | |

| Active In-Person Engagement with Ideas | 0.53 | 0.01 | 60.39 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.55 | |

| _cons | 1.50 | 0.02 | 86.64 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 1.54 | |

| Traditional consumption of ideas | 0.22 | 0.01 | 19.17 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.25 | |

| _cons | 3.49 | 0.03 | 110.19 | 0.00 | 3.42 | 3.55 | |

| Digital exploration of ideas | 0.42 | 0.01 | 41.85 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.44 | |

| _cons | 3.32 | 0.03 | 109.41 | 0.00 | 3.26 | 3.38 | |

| Network | |||||||

| Network size (NW1) | 0.20 | 0.01 | 14.98 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.22 | |

| _cons | 0.61 | 0.01 | 46.79 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.63 | |

| Ideas network centrality (NW2) | 0.57 | 0.01 | 53.78 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.59 | |

| _cons | 1.80 | 0.02 | 93.43 | 0.00 | 1.76 | 1.83 | |

| Network Homophily | 0.58 | 0.01 | 57.03 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.60 | |

| _cons | 4.22 | 0.04 | 112.75 | 0.00 | 4.14 | 4.29 | |

| Network Social Capital | 0.91 | 0.01 | 81.09 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.93 | |

| _cons | 1.85 | 0.02 | 94.53 | 0.00 | 1.81 | 1.89 | |

| Prospection | |||||||

| Q1 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 69.72 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.63 | |

| _cons | 3.96 | 0.04 | 112.00 | 0.00 | 3.89 | 4.03 | |

| Q2 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 83.35 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.69 | |

| _cons | 3.67 | 0.03 | 110.97 | 0.00 | 3.61 | 3.74 | |

| Q3 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 74.88 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.65 | |

| _cons | 4.23 | 0.04 | 112.78 | 0.00 | 4.16 | 4.30 | |

| Q4 | −0.072 | 0.01 | −5.43 | 0.00 | −0.098 | −0.046 | |

| _cons | 3.35 | 0.03 | 109.54 | 0.00 | 3.29 | 3.41 | |

| Q5 | −0.175 | 0.01 | −13.6 | 0.00 | −0.2 | −0.15 | |

| _cons | 3.26 | 0.03 | 109.08 | 0.00 | 3.20 | 3.32 | |

| Q6 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 64.85 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.60 | |

| _cons | 4.00 | 0.04 | 112.10 | 0.00 | 3.93 | 4.07 | |

| Q7 | −0.004 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.75 | −0.031 | 0.02 | |

| _cons | 3.34 | 0.03 | 109.50 | 0.00 | 3.28 | 3.40 | |

| Q8 | −0.004 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.75 | −0.031 | 0.02 | |

| _cons | 3.34 | 0.03 | 109.50 | 0.00 | 3.28 | 3.40 | |

| Q9 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 47.28 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.51 | |

| _cons | 3.95 | 0.04 | 111.97 | 0.00 | 3.88 | 4.02 | |

| Q10 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −5.24 | 0.00 | −0.096 | −0.044 | |

| _cons | 3.31 | 0.03 | 109.34 | 0.00 | 3.25 | 3.37 | |

| Q11 | 0.60 | 0.01 | 68.43 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.62 | |

| _cons | 4.49 | 0.04 | 113.43 | 0.00 | 4.41 | 4.57 | |

| Q12 | 0.60 | 0.01 | 67.87 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.62 | |

| _cons | 4.20 | 0.04 | 112.70 | 0.00 | 4.13 | 4.27 | |

| Q13 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.91 | 0.36 | −0.04 | 0.01 | |

| _cons | 3.33 | 0.03 | 109.48 | 0.00 | 3.27 | 3.39 | |

| Q14 | −0.16 | 0.01 | −12.23 | 0.00 | −0.18 | −0.133 | |

| _cons | 3.00 | 0.03 | 107.56 | 0.00 | 2.94 | 3.05 | |

| Q15 | 0.54 | 0.01 | 55.36 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.56 | |

| _cons | 3.68 | 0.03 | 111.02 | 0.00 | 3.62 | 3.75 | |

| Q16 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 74.11 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.64 | |

| _cons | 4.46 | 0.04 | 113.36 | 0.00 | 4.39 | 4.54 | |

| Q17 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.42 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.09 | |

| _cons | 3.87 | 0.04 | 111.69 | 0.00 | 3.80 | 3.94 | |

| Q18 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 66.84 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.61 | |

| _cons | 3.81 | 0.03 | 111.47 | 0.00 | 3.74 | 3.87 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Ability to think critically (ED2) | 0.162 | 0.012 | 13.16 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.186 | |

| _cons | 2.535 | 0.024 | 103.85 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 2.582 | |

| Q1 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 69.52 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.61 | |

| _cons | 4.59 | 0.04 | 113.65 | 0.00 | 4.51 | 4.67 | |

| Q2 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 91.97 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.69 | |

| _cons | 5.37 | 0.05 | 115.00 | 0.00 | 5.28 | 5.46 | |

| Q3 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 96.62 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.70 | |

| _cons | 5.27 | 0.05 | 114.86 | 0.00 | 5.18 | 5.36 | |

| Q4 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 37.58 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.42 | |

| _cons | 3.69 | 0.03 | 111.06 | 0.00 | 3.63 | 3.76 | |

| Q5 | 0.54 | 0.01 | 58.11 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.56 | |

| _cons | 5.10 | 0.04 | 114.59 | 0.00 | 5.01 | 5.18 | |

| Q6 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 80.85 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.65 | |

| _cons | 5.35 | 0.05 | 114.97 | 0.00 | 5.26 | 5.44 | |

| Q7 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 64.82 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.59 | |

| _cons | 4.07 | 0.04 | 112.34 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.15 | |

| Q8 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 79.77 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.65 | |

| _cons | 4.93 | 0.04 | 114.31 | 0.00 | 4.84 | 5.01 | |

| Q9 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 98.30 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 0.71 | |

| _cons | 5.21 | 0.05 | 114.77 | 0.00 | 5.12 | 5.30 | |

| Q10 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 67.44 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.60 | |

| _cons | 4.51 | 0.04 | 113.47 | 0.00 | 4.43 | 4.59 | |

| Q11 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 57.12 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.55 | |

| _cons | 5.07 | 0.04 | 114.54 | 0.00 | 4.98 | 5.15 | |

| Q12 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 61.73 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.57 | |

| _cons | 5.09 | 0.04 | 114.58 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 5.18 | |

| Q13 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 65.49 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.59 | |

| _cons | 5.16 | 0.05 | 114.69 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 5.25 | |

| Q14 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 68.23 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.60 | |

| _cons | 4.87 | 0.04 | 114.21 | 0.00 | 4.79 | 4.96 | |

| Q15 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 43.77 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.47 | |

| _cons | 4.28 | 0.04 | 112.92 | 0.00 | 4.21 | 4.36 | |

| Able to identify positive and dark ideas effectively | |||||||

| Q1 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 23.95 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.34 | |

| _cons | 1.08 | 0.02 | 72.29 | 0.00 | 1.05 | 1.11 | |

| Q2 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 29.29 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.34 | |

| _cons | 2.51 | 0.02 | 103.58 | 0.00 | 2.46 | 2.56 | |

| Q3 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 14.46 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.23 | |

| _cons | 1.07 | 0.02 | 71.54 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.09 | |

| Q4 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 20.22 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.30 | |

| _cons | 1.29 | 0.02 | 80.15 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 1.32 | |

| Q5 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 4.91 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 | |

| _cons | 1.39 | 0.02 | 83.49 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 1.43 | |

| Q6 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 37.63 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.43 | |

| _cons | 1.84 | 0.02 | 94.22 | 0.00 | 1.80 | 1.88 | |

| Q7 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 14.93 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.23 | |

| _cons | 1.58 | 0.02 | 88.61 | 0.00 | 1.55 | 1.62 | |

| Q8 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 68.20 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.65 | |

| _cons | 2.21 | 0.02 | 100.09 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 2.25 | |

| Q9 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 26.46 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.37 | |

| _cons | 1.15 | 0.02 | 75.14 | 0.00 | 1.12 | 1.18 | |

| Q10 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 55.20 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.56 | |

| _cons | 2.22 | 0.02 | 100.24 | 0.00 | 2.17 | 2.26 | |

| Q11 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 55.82 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.57 | |

| _cons | 3.64 | 0.03 | 110.84 | 0.00 | 3.57 | 3.70 | |

| Q12 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 29.66 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.35 | |

| _cons | 2.30 | 0.02 | 101.30 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 2.35 | |

References

- Campbell, D. ‘Dire Need’ for Labels on Alcohol and Ads About Unhealthy Eating to Cut Avoidable Cancers. The Guardian. 16 September 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/sep/16/dire-need-for-labels-on-alcohol-and-ads-about-unhealthy-eating-to-cut-avoidable-cancers (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Castling, J.; Johnston, J. Curiosity and Stories: Working with art and archaeology to encourage the growth of cultural capital in local communities. In The Ideas-Informed Society: Why We Need It And How to Make It Happen; Brown, C., Handscombe, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2023; pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on the grades of U.S. high school students. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 47, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Sousa, A.S.; Viera, R.M. How To Become An Informed Citizen In The (Dis)Information Society? Recommendations And Strategies To Mobilize One’s Critical Thinking. Sinergias—Di Logos Educativos Para a Transformação Social 2019, 9, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, J. If Democracies Need Informed Voters, How Can They Thrive While Expanding Enfranchisement? Elect. Law J. Rules Politics Policy 2010, 9, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, S. Enlightenment Now The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, 1st ed.; Penguin: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. How Social Science Can Help Us Make Better Choices: Optimal Rationality in Action, 1st ed.; Emerald Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.; Luzmore, R. An educated society is an ideas-informed society: A proposed theoretical framework for effective ideas engagement. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2024; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C. The Case for Climate Populism. The New Statesman, 14–20 February 2025; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.; Groß Ophoff, J.; Chadwick, K.; Parkinson, S. Achieving the ‘ideas-informed’ society: Results from a Structural Equation Model using survey data from England. Emerald Open Res. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. The Amazing Power of Networks. A [Research-Informed] Choose Your Own Destiny Book, 1st ed.; John Catt: Woodbridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Social Justice. Two Nations. The State of Poverty in the UK: An Interim Report on the State of the Nation. 2023. Available online: https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/the-social-justice-commission (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- D’Ancona, M. Post Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back; Ebury Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, D.; Frissen, T.; Matthijs, K.; d’Haenens, L.; Lits, G.; Champagne-Poirier, O.; Carignan, M.E.; David, M.D.; Pignard-Cheynel, N.; Salerno, S.; et al. Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation About COVID-19: Comparative Perspectives on the Role of Anxiety, Depression and Exposure to and Trust in Information Sources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, C. The Science of Weird Shit: Why Our Minds Conjure the Paranormal; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, B. What Is Germany’s ‘Reichsbürger’ movement? Deutsche Welle. 29 April 2024. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/what-is-germanys-reichsbürger-movement/a-36094740 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Popli, N.; Zorthian, J. What Happened to the Jan. 6 Rioters Arrested Since the Capitol Attack. Time. 6 January 2023. Available online: https://time.com/6133336/jan-6-capitol-riot-arrests-sentences/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Rajvanshi, A. How U.K. Immigration Lawyers Became a Target of Far-Right Riots. Time. 8 August 2024. Available online: https://time.com/7009130/uk-riots-immigration-lawyers/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- OECD. OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions 2024 Results—Country Notes: United Kingdom. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-survey-on-drivers-of-trust-in-public-institutions-2024-results-country-notes_a8004759-en/united-kingdom_cec47bf8-en.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Feinstein, N.; Baram-Tsabari, A. Epistemic networks and the social nature of public engagement with science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2024, 16, 2049–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, D.J.; Grim, P.; Bramson, A.; Holman, B.; Jung, J.; Berger, W.J. Epistemic networks and polarization. In The Routledge Handbook of Political Epistemology; Hannon, M., de Ridder, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jermone, L.; Kisby, B.; McKay, S. Combatting conspiracies in the classroom: Teacher strategies and perceived outcomes. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2023, 50, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyreva, A.; Lorenz-Spreen, P.; Herzog, S.M.; Ecker, U.K.; Lewandowsky, S.; Hertwig, R.; Ali, A.; Bak-Coleman, J.; Barzilai, S.; Basol, M.; et al. Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online misinformation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasser, J.; Aroyehun, S.T.; Carrella, F.; Simchon, A.; Garcia, D.; Lewandowsky, S. From alternative conceptions of honesty to alternative facts in communications by US politicians. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz-Spreen, P.; Oswald, L.; Lewandowsky, S.; Hertwig, R. A systematic review of worldwide causal and correlational evidence on digital media and democracy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.; Vermueule, A. Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures. J. Political Philos. 2009, 17, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerwer, M.; Rosman, T. Mechanisms of Epistemic Change—Under Which Circumstances Does Diverging Information Support Epistemic Development? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, D.S.; Stoddard, J.D. “It’s a Growing and Serious Problem:” Teaching 9/11 to Combat Misinformation and Conspiracy Theories. Soc. Stud. 2021, 112, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y.; Faris, R.; Roberts, H. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics, Online ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Cook, J. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2017, 6, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E.M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Cichocka, A. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 26, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Luzmore, R.; Groß Ophoff, J. Facilitating the Ideas informed Society: A systematic review. Emerald Open Res. 2022, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Groß Ophoff, J. Exploring effective approaches for stimulating ideas-engagement amongst adults in England: Results from a randomised control trial. Emerald Open Res. 2022, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Luzmore, R. Educating Tomorrow: Learning for the Post-Pandemic World, 1st ed.; Emerald Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arechar, A.A.; Allen, J.; Berinsky, A.J.; Cole, R.; Epstein, Z.; Garimella, K.; Gully, A.; Lu, J.G.; Ross, R.M.; Stagnaro, M.N.; et al. Understanding and combatting misinformation across 16 countries on six continents. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couchman, J.J.; Miller, N.E.; Zmuda, S.J.; Feather, K.; Schwartzmeyer, T. The instinct fallacy: The metacognition of answering and revising during college exams. Metacognition Learn. 2016, 11, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.; Brown, C.; Aldridge, D. Meta-reflexivity and teacher professionalism: Facilitating multi-paradigmatic teacher education to achieve a future-proof profession. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 74, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.A.; Yu, S.B. Educating critical thinkers: The role of epistemic cognition. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2016, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, C.R.; Kuncel, N.R. Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 431–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.; Fowler, J. Connected: The Amazing Power of Social Networks and How They Shape our Lives, 1st ed.; Harper Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. The Human Network: How We’re Connected and Why It Matters, 1st ed.; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Erisen, E.; Erisen, C. The effect of social networks on the quality of political thinking. Political Psychol. 2012, 33, 839–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Z. The Connected City: How Networks Are Shaping the Modern Metropolis, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Bowing Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community, 1st ed.; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.; Lim, K. Prospection. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible; Glăveanu, V.P., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1392–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.; Vohs, K.; Oettingen, G. Pragmatic Prospection: How and Why People Think About the Future. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016, 20, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataranutaporn, P.; Winson, K.; Yin, P.; Lapapirojn, A.; Ouppaphan, P.; Lertsutthiwong, M.; Maes, P.; Hershfield, H. Future You: A Conversation with an AI-Generated Future Self Reduces Anxiety, Negative Emotions, and Increases Future Self-Continuity. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024. (pre-print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettingen, G.; Mayer, D. The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Khazanov, G.K.; Reece, A.; Kellerman, G. Development and Validation of the Pragmatic Prospection Scale, a Measure of Constructive Future Thinking. Manuscr. Prep. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, P.M.; Greenhalgh, T. Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. Br. Med. J. 2004, 328, 1312–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, M.; Kaasa, A. Do dimensions of culture exist objectively? A validation of the revised Minkov-Hofstede model of culture with World Values Survey items and scores for 102 countries. J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, 1st ed.; Sage: Beverley Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S. Applying structural equation modelling to research on teaching and teacher education: Looking back and forward. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 107, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado–Tello, F.P.; Chacón–Moscoso, S.; Barbero–García, I.; Vila–Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Luzmore, R.; Wang, Y. Education, prospection and social-networks: Surveying ideas-engagement amongst 7,000 respondents across seven European countries. Qual. Educ. All 2025. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Hayes, A.F., Slater, M.D., Snyder, L.B., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Beverley Hills, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infoart.ca. Understanding Path Analysis: Paths, Standardized Coefficients and Causality. 2025. Available online: https://infoart.medium.com/understanding-path-analysis-paths-standardized-coefficients-and-causality-acd52d3d847c (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, B.; Rand, D.G.; Pennycook, G. Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 149, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, J.; Copland, E.; Loh, E.; Sunstein, C.; Sharot, T. Epistemic spillovers: Learning others’ political views reduces the ability to assess and use their expertise in nonpolitical domains. Cognition 2019, 188, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathje, S.; Roozenbeek, J.; Van Bavel, J.J.; Van Der Linden, S. Accuracy and social motivations shape judgements of (mis) information. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, W. Hopes and Fears for Art; Longmans, Green and Co.: London, UK, 1908; Available online: https://ia600904.us.archive.org/28/items/hopesfearsforar00morr/hopesfearsforar00morr.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).