1. Introduction

The role of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in sustainability dates back to the 1972 Stockholm Conference, which laid the foundation for integrating environmental concerns into education [

1]. In the following decades, sustainability gained increasing global attention, leading to the adoption of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 195 nations in 2015 as a universal framework for sustainable development [

2]. The SDGs consist of 17 objectives, further detailed through 169 targets and measured by 247 indicators, establishing a structured framework to address critical global challenges. However, Sustainability has faced severe setbacks caused by COVID-19, armed conflicts, climate shocks, and economic instability [

3,

4] as emphasized by the 2024 SDGs Report. The broad scope of SDGs presents considerable challenges for measuring and tracking progress. Accurate assessments rely on reliable, high-quality data. However, outdated, incomplete, or inconsistent data undermines the accuracy of SDG evaluations, impeding meaningful progress tracking. Insufficient data remain a significant barrier to effectively monitoring SDG progress over time and across countries [

5]. HEIs face similar challenges in terms of data reliability and availability as they strive to integrate sustainability goals into their academic and operational strategies [

6]. On the other hand, HEIs play a pivotal role in advancing sustainability by integrating SDGs into their curricula, research, and operations [

7,

8]. Through education, students equipped with skills to address global challenges, while their research drives innovation and systemic change [

9]. HEIs are also led by implementing institutional initiatives that optimize resources and foster collaboration. By leveraging their expertise in knowledge creation, they develop practical solutions for sustainability and align themselves with global objectives, reinforcing their transformative impact on society [

10,

11].

The need to evaluate the progress of sustainability in HEIs has been widely acknowledged, leading to the development of various sustainability assessment frameworks [

12,

13]. These systems provide valuable insights into institutional performance; however, they often face criticism for their methodological limitations, lack of transparency, and inadequate adaptation to diverse institutional contexts [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Many existing approaches emphasize global benchmarking at the expense of institution-specific insights and actionable strategies. Their focus on specific SDGs can lead to imbalances in reporting, as universities highlight strengths while underrepresenting other critical dimensions of sustainability [

18]. Additionally, inconsistencies in SDG reporting reflect regional and institutional disparities, reinforcing existing hierarchies rather than fostering meaningful change [

8,

19]. Overly standardized methodologies risk reducing universities to mere data providers rather than active contributors to sustainability transformation [

20]. A more inclusive approach, one that integrates diverse perspectives and fosters broader stakeholder participation, is essential to capture the full scope of sustainability efforts in HEIs [

11].

To address these challenges, a flexible and transparent evaluation system is required to provide recommendations for continuous improvement. A structured and context-sensitive assessment framework helps overcome the limitations of traditional ranking methodologies, offering a more accurate and equitable evaluation of HEIs’ sustainability. Emphasizing holistic sustainability assessments, this approach advocates a shift from incomplete or selective data representation to an inclusive, data-driven methodology that empowers HEIs to make informed decisions and advance their sustainability commitments effectively.

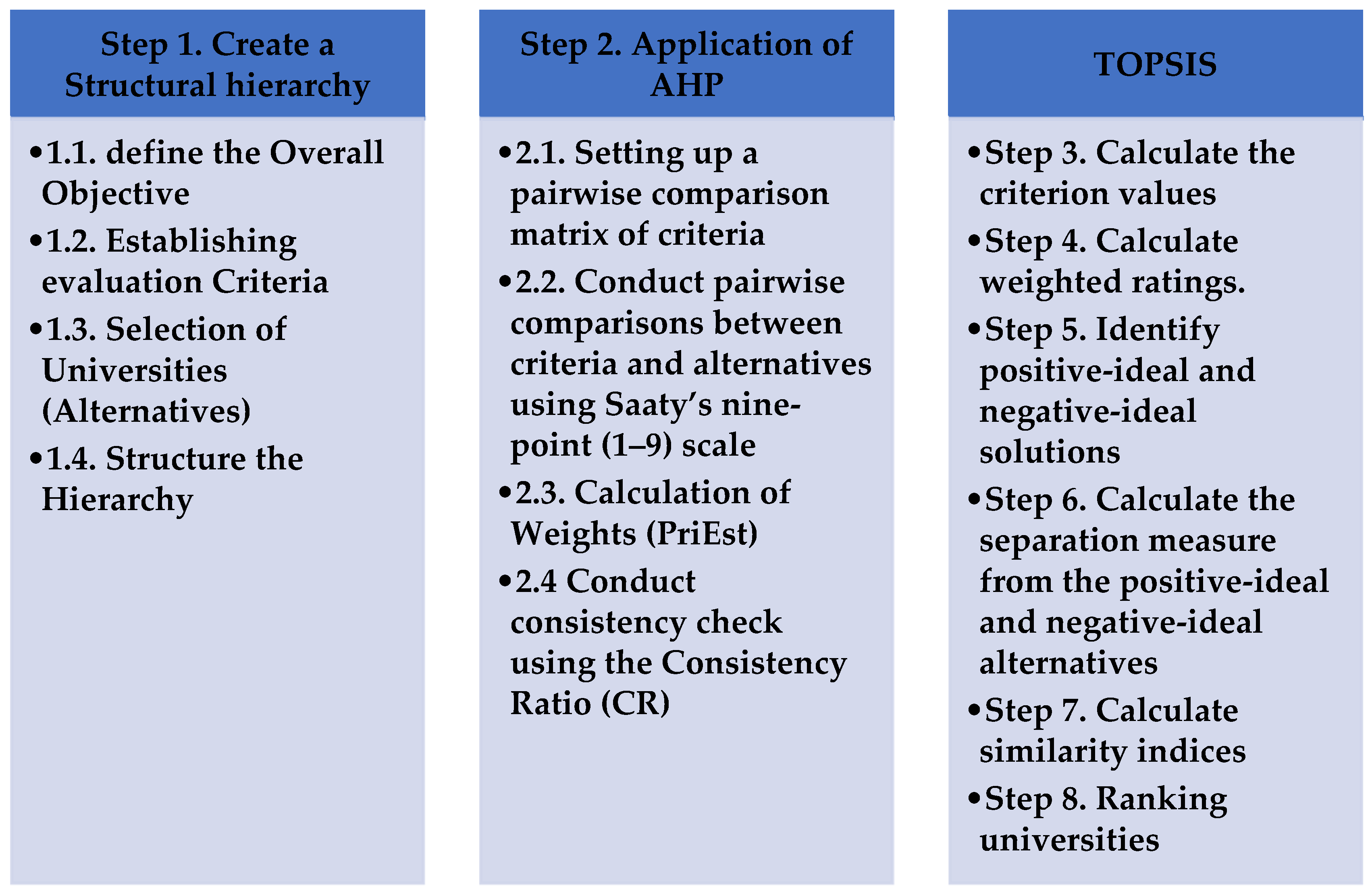

This paper introduces a structured framework for evaluating HEIs’ progress toward SDGs, offering a comprehensive assessment of institutional strengths and weaknesses. To achieve this, the framework integrates two Multi-Criteria Decision-Making/Analysis (MCDM/A) methods: the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [

21] and the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [

22,

23,

24]. To simplify the process, the proposed framework is referred to as Multi-criteria Decision-making for hEI Sustainability (MUDEIS).

MUDEIS does not attempt to introduce new MCDM algorithms; instead, its contribution lies in offering a structured, transparent, and fully operationalized evaluation framework that integrates all 17 SDGs and 34 indicators into a coherent AHP–TOPSIS decision-support system tailored to HEIs. This fills a methodological gap in existing sustainability assessment tools, which typically emphasize limited SDG subsets or rely on opaque aggregation methods. MUDEIS’s innovation is practical rather than algorithmic, providing a replicable architecture that can be extended in future work with machine-learning–based dynamic weighting and big-data inputs.

AHP, developed in [

21], systematically quantifies qualitative factors through expert input and derives weights for each criterion. These weights are then used in TOPSIS, a distance-based analysis method that ranks institutions based on their proximity to an optimal solution. By combining these approaches, the framework provides a robust and equitable evaluation of HEIs’ contributions across all 17 SDGs.

Unlike existing systems that allow selective reporting, this framework requires comprehensive data across the entire spectrum of SDGs, promoting holistic assessments of institutional sustainability and enabling longitudinal tracking for continuous improvement [

7,

11]. In TOPSIS, institutions that are closer to an ideal HEI and farther from the poorest-performing HEI receive higher rankings, making this approach particularly effective for differentiating performance levels. This methodology aligns institutional efforts with global sustainability objectives, thereby driving meaningful and measurable progress in SDG integration [

24,

25]. The application of TOPSIS provides a structured and effective approach for institutions to enhance their adaptation and integration.

Each institution exhibits unique strengths and faces distinct challenges, underscoring the importance of context-specific strategies, effective resource allocation, and clear alignment of institutional priorities with SDG goals. Adopting strategic recommendations, such as fostering inclusivity, strengthening environmental initiatives, and leveraging partnerships, allows HEIs to enhance their contributions to sustainability. These insights provide a roadmap for institutions seeking to align their operations with global sustainability objectives, reinforcing their pivotal role as catalysts for positive societal and environmental changes.

AHP was selected due to its suitability for capturing expert-derived SDG priorities in a transparent and interpretable manner, supported by consistency checks (CR < 0.10). TOPSIS was chosen because it provides an intuitive similarity-to-ideal score and supports the simultaneous inclusion of benefit and cost indicators. Alternative outranking methods such as ELECTRE or PROMETHEE require preference/indifference thresholds, which are difficult to define consistently across 34 heterogeneous indicators. Therefore, the AHP–TOPSIS combination offers the most transparent, scalable, and stakeholder-friendly approach for HEIs.

The paper begins by establishing the need for an evaluation and recommendation system specifically tailored to HEIs.

Section 2 outlines MUDEIS and provides a comprehensive overview of the methodology.

Section 3 introduces the indicators and criteria for evaluating SDGs in HEIs. In

Section 4, we explain the application of AHP to systematically derive the weights assigned to the selected criteria.

Section 5 delves into the distribution and implications of these weights and highlights key trends and institutional priorities.

Section 6 describes the use of the TOPSIS in ranking and assessing HEI sustainability performance.

Section 7 presents an example of how the framework works using fictional university profiles, demonstrating its adaptability and effectiveness.

Section 8 offers an in-depth exploration of the results, emphasizing the strengths and limitations of the proposed system and providing recommendations for improvement. Finally,

Section 8 synthesizes the key findings and outlines potential areas for future research to enhance the evaluation and recommendation frameworks.

4. Weights of Criteria

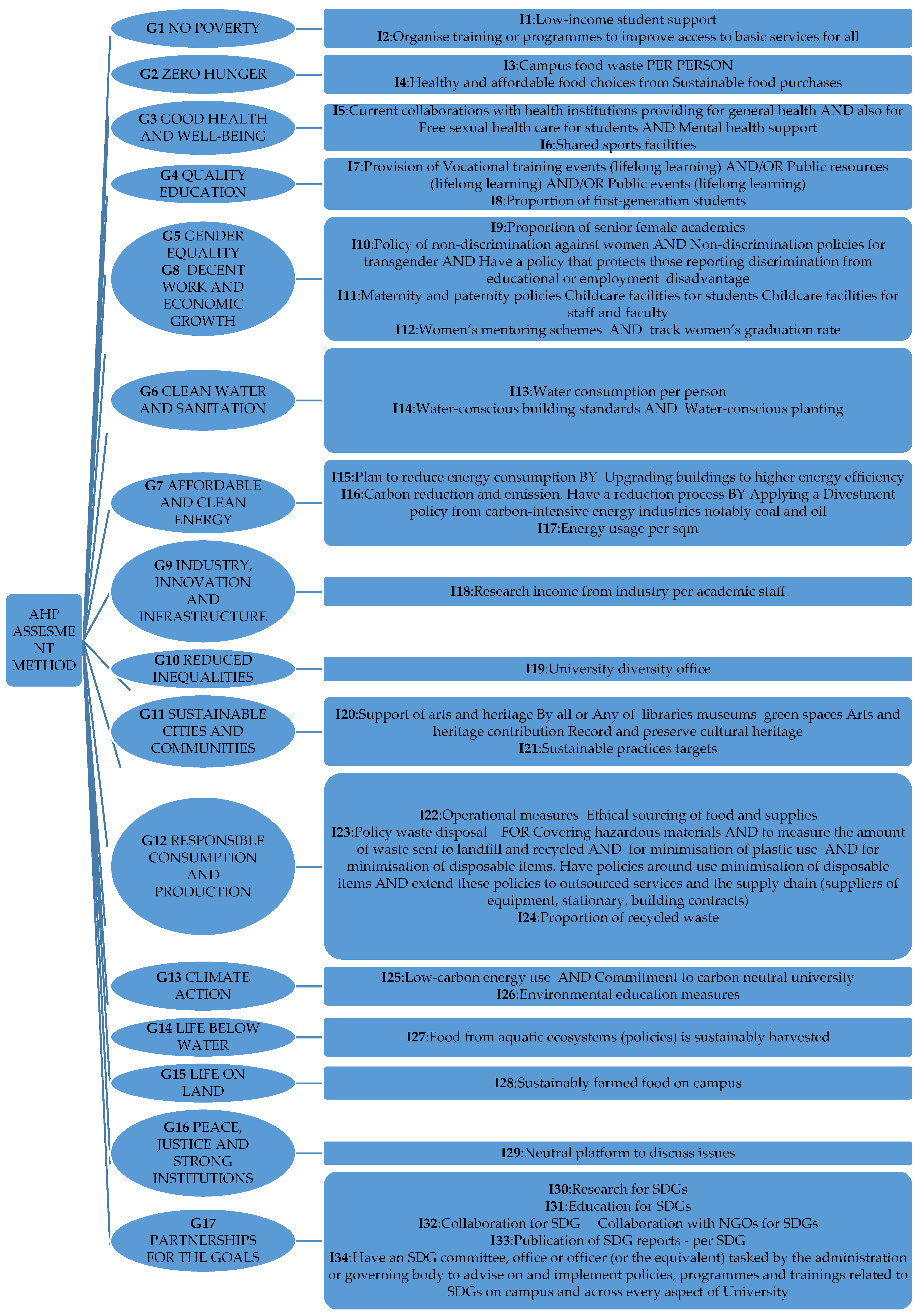

Building on a comprehensive set of 34 indicators introduced in [

26], AHP was applied to calculate the weights of the criteria. AHP is a pairwise comparison methodology that involves key stages such as establishing a goal hierarchy, developing a pairwise comparison matrix with expert input, and calculating criteria weights. This approach enabled the precise prioritization of factors, integrating both qualitative and quantitative elements to address the multifaceted challenges of sustainability assessments. For the implementation of AHP, we used PriEst software (v2017) [

28]. A detailed methodology is presented in [

27]. The resulting weights quantify the relative importance of each criterion, providing a robust foundation for ranking sustainability priorities.

Ten experts were selected using purposive sampling to ensure representation across sustainability-related domains within Greek higher education. These experts simultaneously met the following qualifications: having professional experience in the university area, more than 30 years of professional experience in sustainability matters, and over 30 years of professional administrative experience at the university. Their expertise ranged from energy matters to environmental construction projects, environmental projects, and cultural projects.

The selected professionals represented a diverse range of expertise within academia, particularly in fields related to engineering, environmental science, conservation, and administration. They held positions ranging from professors to deans, deputy directors, and vice-rectors to rectors. Their positions in the university indicate their significant experience and leadership roles within their respective departments, including mechanical engineering with a focus on energy systems, environmental protection, and optimization of production systems; electrical and electronic engineering with expertise in power electronics and renewable energy sources; conservation of antiquities and works of art and cultural heritage management; environmental management and SD; and personalized software technology with applications in environmental studies. These individuals collectively possess extensive experience, with most having over 30 years in their fields, demonstrating a deep understanding of the environmental, educational, and administrative domains. Their expertise extends beyond academia, with involvement in the consultancy and private and public sectors, reflecting their multidimensional contributions to their respective fields.

Given their extensive background, these evaluators aptly represent the prevalent practices and viewpoints of the Greek university sector. They are entrusted with evaluating the criteria and assigning relative scales to determine the importance of criteria or sub-criteria within the AHP model. Typically, a representative sample of three to seven (often five) evaluators is selected to assign relative scales, as per the literature and empirical observations. Research indicates that as the number of evaluators increases, the relative gains diminish and the complexity of collecting pairwise comparison judgments increases. Hence, ten evaluators were chosen for this assessment [

29].

To conduct pairwise comparisons, the nine-point scale, as suggested by Saaty, was used to assign relative scales [

21,

29]. Individual pairwise-comparison matrices were aggregated into a single group matrix using the geometric mean, the theoretically appropriate operator for AHP group decision-making because it preserves reciprocity [

30]. All pairwise matrices achieved acceptable consistency, with CR values ranging from 0.005 to 0.068. The top-level SDG matrix yielded CR = 0.036 (<0.10), indicating coherent and stable expert judgments.

The derived criteria weights, presented in

Table 1, illustrate the relative importance assigned to each SDG-related criterion. A geometric mean was used to consolidate the individual judgments of the ten experts to ensure consistency across the analysis. All comparisons achieved consistency ratios (CR) below 0.10, confirming the reliability of the evaluations.

MUDEIS incorporates an optional handling mechanism for SDGs that are structurally irrelevant to certain HEIs. For example, SDG 14 (Life Below Water) may not be applicable to landlocked institutions with no marine or coastal activities. In such cases, two options are available: (i) the indicator can be assigned a zero weight, or (ii) it can be marked as “Not Applicable” (NA) and excluded from the normalization process. In both cases, the remaining weights are automatically rescaled so that the total weight vector remains equal to 1.

This approach ensures that institutions are neither penalized nor rewarded for goals outside their operational mandate, while maintaining comparability across contexts. The mechanism prevents bias introduced by irrelevant indicators, supports fairness across heterogeneous HEIs, and preserves the internal logic of the AHP–TOPSIS procedure.

Key trends emerged from the analysis, with environmental management and social equity identified as the highest-priority criteria. These findings highlight the critical need to address both environmental and social dimensions to effectively advance HEI sustainability initiatives.

5. Analyzing the Priority Weights of SDGs in HEIs

The analysis of SDG priority weights in HEIs is presented in

Table 1, which offers valuable insights into how universities align their strategies with global sustainability objectives. This prioritization reflects HEIs’ institutional missions and societal responsibilities, highlighting their focus on education and the broader impacts of their efforts.

High-Priority Goals (weights from 0.210 to 0.100): SDG 4 (Quality Education).

The prioritization of SDG 4 affirms HEIs’ primary mission of fostering education and knowledge creation.

Medium-Priority Goals (Weights from 0.099–0.054): SDG 5 + 8 (Gender Equality + Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 06 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 2 (Zero hunger), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 1 (No poverty).

HEIs balance their educational focus with contributions to inclusivity, well-being, and environmental stewardship. SDG 5 and SDG 8 emphasize equity and inclusivity through policies such as non-discrimination initiatives and family-friendly practices. SDG 3 reflects HEIs’ efforts in to support mental and physical health, while SDG 7 and SDG 6 demonstrate their role in promoting resource-efficient practices and environmental responsibility.

Low-Priority Goals (weights: 0.051–0.037): SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

Goals such as SDG 13, SDG 11, SDG 16, and SDG 9 hold moderate attention, often addressed through green infrastructure projects and collaborative community efforts, still contributing to HEIs’ overall sustainability impact.

Very Low-Priority Goals (weights: 0.025–0.023): SDG 15 (Life on Land) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

SDG 15 and SDG 14 are assigned the lowest weights, reflecting their limited direct applicability to many HEIs, especially those in non-coastal regions.

The analysis of the priority weights provides actionable insights for developing comprehensive sustainability strategies for HEIs. High-priority SDGs such as SDG 4 should remain central to institutional objectives, ensuring alignment with educational missions. Moderate-priority goals, such as SDGs 5, 8, 3, 7, 2, 10, and 1 emphasize the importance of equity and diversity, which can be integrated through policies such as inclusive hiring, student support programs, and family-friendly initiatives. HEIs can further extend their impact by addressing low-priority SDGs through targeted strategies, including partnerships with environmental organizations, interdisciplinary research, and community-focused programs. This balanced approach ensures that HEIs remain committed to their educational mission while meaningfully contributing to broader global sustainability objectives. Ultimately, this strategic alignment positions HEIs as key actors in achieving SDGs, reinforcing their role as catalysts for local and global progress.

6. Application of TOPSIS

In the proposed MUDEIS framework, TOPSIS is used to combine the values of the criteria and weights to evaluate the HEI. The steps of MUDEIS that involve the application of TOPSIS are as follows.

Step 3. Calculate the criterion values. In this step, TOPSIS is implemented to evaluate each university based on the criteria selected in Step 1.2. We run the simulation for the universities described in

Table 2. The values given for each criterion were derived from the evaluation

Table 3 and

Table 4. The university gets the values depending on the fulfillment of certain criteria so the values are comparable.

All indicators were normalized using min–max scaling, with benefit indicators increasing positively with higher values and cost indicators reversed. Standardization followed the formula:

for benefit indicators, and

for cost indicators. To support methodological transparency and ensure that each indicator is fully interpretable and reproducible, an operationalization rubric has been added. The rubric in the repository Link provides, for all 34 indicators, the definition, measurement procedure, unit or scale of evaluation, orientation (benefit or cost), data source, and NA-handling rule. This table clarifies the exact meaning and use of each indicator in MUDEIS and enables consistent application across different HEIs.

The full operationalization rubric is presented in the repository Link.

The application of TOPSIS and the following steps were conducted as described in [

31,

32], who combined AHP with TOPSIS in a completely different domain: the e-commerce domain.

Step 4. Calculate weighted ratings. The weighted value is calculated as:

where w

i is the weight and r

ij is the value of the ith criterion.

Step 5. Identify positive-ideal and negative-ideal solutions. The positive-ideal solution is the composite of all the best criteria ratings attainable, and it is denoted as:

where

is the best value for the ith criterion among all alternatives. The negative-ideal solution is the composite of all the worst criterion ratings attainable, and it is denoted as:

where

is the worst value for the ith criterion among all alternatives.

Step 6. Calculate the separation measure from the positive-ideal and negative-ideal alternatives. The separation of each alternative from the positive-ideal solution,

, is given by the

n-dimensional Euclidean distance:

where

j is the index related to the alternatives and

i is each one of the

n criteria. Similarly, the separation from the negative-ideal solution

is as follows:

shows how close the HEI is to the ideal HEI created during the implementation of the MUDEIS.

shows the closeness of the HEI evaluated with the fictional negative HEI.

Step 7. Calculate similarity indices. The similarity to the positive-ideal solution for alternative j is given by:

The alternatives can then be ranked in descending order according to

. Conclusions can be drawn by considering how close an HEI is to the ideal one or how further it is from the fictional worst.

Step 8. Ranking universities. The similarity indices are further used to rank the universities that are evaluated, and those with the higher values are categorized first.

To evaluate the functionality and adaptability of the proposed MUDEIS framework, a simulation-based approach was employed. Due to limitations in accessing complete and standardized sustainability data from actual higher education institutions (HEIs), three fictional universities were developed to simulate various institutional profiles. These simulated HEIs differ in size, academic focus, geographic location, and policy alignment with the SDGs. The purpose of this simulation is to test the framework’s ability to handle diverse institutional scenarios and assess how it responds to variations in performance across SDG-related indicators.

Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the three simulated universities. A base year (2022) was set for reference, followed by two consecutive years (2023 and 2024) to examine institutional evolution and allow comparative analysis across time and institutional types.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of simulated universities.

| | University 1

Newly Established University in Region in a Remote Area Scattered in Various Islands | University 2

Well Established University. in Central Area (Capital) Focused on a Specific Subject | University 3

Well Established in Central Region with Wide Range of Faculties |

|---|

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Campus Population | 12.000 | 12.850 | 12.750 | 4.200 | 3.850 | 4.200 | 25.850 | 26.180 | 27.950 |

| Academic Staff | 255 | 262 | 263 | 102 | 99 | 102 | 1211 | 1225 | 1225 |

Female

Senior

Academics | 77 | 86 | 87 | 38 | 43 | 34 | 389 | 502 | 450 |

| Floor Space (m2) | 46.700 | 46.700 | 46.700 | 19.888 | 22.700 | 22.700 | 112.000 | 126.700 | 126.700 |

| Student Enrollment | 1.600 | 1.750 | 1.920 | 350 | 240 | 340 | 4.300 | 5.500 | 6.320 |

| Students Completing a Degree | 980 | 1.225 | 1.978 | 289 | 202 | 289 | 4.950 | 5.700 | 4.078 |

| Sustainability Policies and Initiatives | strategic focus on implementing policies and programs aligned with the SDGs | demonstrates partial alignment with various SDGs. implementing key policies and initiatives while facing challenges in others. | has demonstrated varying levels of commitment to SDG adoption |

| -2023 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.30 |

| -2024 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

The data in this simulation were constructed to reflect plausible yet hypothetical values, based on typical performance metrics observed in higher education institutions (HEIs). The MUDEIS framework, which integrates AHP and TOPSIS, was applied to these simulated university profiles to test its functionality across varying conditions.

For this simulation, three consecutive years were used to evaluate temporal trends and institutional evolution. While the chosen years are 2022 to 2024, it is important to note that this time frame is entirely hypothetical and could represent any three-year period, as the data are fictional. The year 2022 was designated as the base year to establish a point of reference, with simulated data provided for 2023 and 2024.

This structure allows for a longitudinal comparison of institutional performance in terms of size, academic maturity, and sustainability engagement. By examining progression across three simulated years, the framework captures both inter-institutional variation and intra-institutional trends over time.

In

Table 3 and

Table 4, we present the detailed results of the TOPSIS simulation evaluations for 2023 and 2024, respectively. These include similarity indices (C

j*), which indicate each university’s relative proximity to the ideal solution. The outcomes demonstrate MUDEIS’s capacity to distinguish performance levels across institutions and validate its applicability as a decision-support tool, even in the absence of real-world data.

Table 3.

Calculations and results for MUDEIS 2023.

| TOPSIS 2023 |

|---|

| | | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | University 1 | University 1 | University 2 | University 2 | University 3 | University 3 |

|---|

| SDG | Indicator Code | wIi ∗ Values | wIi ∗ Values | wIi ∗ Values | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 |

|---|

| SDG01 | I1 | 1.764 | 2.352 | 0.98 | 0.345744 | 0.614656 | 0 | 1.882384 | 1.882384 | 0 |

| | I2 | 0.486 | 0.648 | 0.27 | 0.026244 | 0.046656 | 0 | 0.142884 | 0.142884 | 0 |

| SDG02 | I3 | 0.728822279 | 0.623894558 | 0.709850746 | 0 | 0.011009827 | 0.011009827 | 0 | 0.000359919 | 0.007388466 |

| | I4 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 0.525 | 0 | 0.540225 | 0 | 0.540225 | 0.540225 | 0 |

| SDG03 | I5 | 1.989 | 1.49175 | 1.989 | 0 | 0.247257563 | 0.247257563 | 0 | 0 | 0.247257563 |

| | I6 | 0 | 0 | 1.011 | 1.022121 | 0 | 1.022121 | 0 | 0 | 1.022121 |

| SDG04 | I7 | 2.103 | 2.103 | 0 | 0 | 4.422609 | 0 | 4.422609 | 4.422609 | 0 |

| | I8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SDG05

+

SDG08 | I9 | 0.209799247 | 0.225012759 | 0.207428015 | 0.000231451 | 5.62274 × 10−6 | 0 | 0.000309223 | 0.000309223 | 0 |

| I10 | 0.771 | 0.771 | 0.514 | 0 | 0.066049 | 0 | 0.066049 | 0.066049 | 0 |

| I11 | 1.281 | 0 | 0.854 | 0 | 1.640961 | 1.640961 | 0 | 0.182329 | 0.729316 |

| | I12 | 0 | 0 | 0.123 | 0.015129 | 0 | 0.015129 | 0 | 0 | 0.015129 |

| SDG06 | I13 | 0.622729693 | 0.659648972 | 0 | 0.001363033 | 0.387792271 | 0 | 0.435136766 | 0.435136766 | 0 |

| | I14 | 0.896 | 1.344 | 1.344 | 0.200704 | 0 | 0 | 0.200704 | 0 | 0.200704 |

| SDG07 | I15 | 1.74 | 1.74 | 1.74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| | I16 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| | I17 | 0.176898852 | 0.232038776 | 0.199506606 | 0.003040411 | 0 | 0 | 0.003040411 | 0.001058342 | 0.000511111 |

| SDG09 | I18 | 1.111277853 | 1.75848 × 10−5 | 1.070739211 | 0 | 1.234899383 | 1.234899383 | 0 | 0.001643381 | 1.146444802 |

| SDG10 | I19 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| SDG11 | I20 | 0 | 1.04625 | 1.395 | 1.946025 | 0 | 0.121626563 | 1.094639063 | 0 | 1.946025 |

| | I21 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0 | 0 | 1.1449 | 0 | 1.1449 | 1.1449 | 0 |

| SDG12 | I22 | 0.873 | 0.873 | 0 | 0 | 0.762129 | 0 | 0.762129 | 0.762129 | 0 |

| | I23 | 1.266 | 1.266 | 0.844 | 0 | 0.178084 | 0 | 0.178084 | 0.178084 | 0 |

| | I24 | 0.268884954 | 0 | 0.319442677 | 0.002556083 | 0.072299119 | 0.102043624 | 0 | 0 | 0.102043624 |

| SDG13 | I25 | 1.178 | 0.589 | 1.178 | 0 | 0.346921 | 0.346921 | 0 | 0 | 0.346921 |

| | I26 | 1.233 | 1.233 | 0 | 0 | 1.520289 | 0 | 1.520289 | 1.520289 | 0 |

| SDG14 | I27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SDG15 | I28 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| SDG16 | I29 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SDG17 | I30 | 0.252355357 | 0.251486402 | 0.238753413 | 0 | 0.000185013 | 7.55081 × 10−7 | 0.000162129 | 0.000185013 | 0 |

| | I31 | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0 | 0 | 0.933156 | 0 | 0.933156 | 0.933156 | 0 |

| | I32 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| | I33 | 0 | 0.342 | 0 | 0.116964 | 0 | 0 | 0.116964 | 0.116964 | 0 |

| | I34 | 0.429 | 0.429 | 0.429 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| | | | | | 12.68012198 | 23.1700838 | 4.741969714 | 31.44366459 | 30.33069464 | 5.763861565 |

| | | | | | 3.56091589 | 4.813531323 | 2.177606418 | 5.607465077 | 5.507330991 | 2.400804358 |

| = /( + ) | | | | | | 0.574787947 | | 0.720284339 | | 0.303586655 |

Table 4.

Calculations and results for MUDEIS 2024.

| TOPSIS 2024 |

|---|

| | | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | University 1 | University 1 | University 2 | University 2 | University 3 | University 3 |

|---|

| SDG | Indicator

Code | wIi ∗ Values | wIi ∗ Values | wIi ∗ Values | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 | (vij − v∗)2 | (vij − v−)2 |

|---|

| SDG01 | I1 | 2.352 | 0.98 | 1.568 | 0 | 1.882384 | 1.882384 | 0 | 0.614656 | 0.345744 |

| | I2 | 0.648 | 0.27 | 0.432 | 0 | 0.142884 | 0.142884 | 0 | 0.046656 | 0.026244 |

| SDG02 | I3 | 0.805326705 | 0 | 0.855373666 | 0.002504698 | 0.648551101 | 0.731664109 | 0 | 0 | 0.731664109 |

| | I4 | 1.26 | 0.525 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.540225 | 0.540225 | 0 | 0.1764 | 0.099225 |

| SDG03 | I5 | 1.989 | 0.82875 | 1.989 | 0 | 1.346180063 | 1.346180063 | 0 | 0 | 1.346180063 |

| | I6 | 1.011 | 0.42125 | 1.011 | 0 | 0.347805063 | 0.347805063 | 0 | 0 | 0.347805063 |

| SDG04 | I7 | 2.103 | 0.87625 | 0.701 | 0 | 1.965604 | 1.504915563 | 0.030712563 | 1.965604 | 0 |

| | I8 | 0.326181818 | 0 | 0.533430432 | 0.042951988 | 0.106394579 | 0.284548026 | 0 | 0 | 0.284548026 |

SDG05

+

SDG08 | I9 | 0.211431781 | 0 | 0.211495231 | 4.02588 × 10−9 | 0.044703398 | 0.044730233 | 0 | 0 | 0.044730233 |

| I10 | 0.771 | 0 | 0.771 | 0 | 0.594441 | 0.594441 | 0 | 0 | 0.594441 |

| I11 | 1.281 | 0 | 1.281 | 0 | 1.640961 | 1.640961 | 0 | 0 | 1.640961 |

| | I12 | 0.369 | 0 | 0.246 | 0 | 0.136161 | 0.136161 | 0 | 0.015129 | 0.060516 |

| SDG06 | I13 | 0.642019848 | 0 | 0.510911598 | 0 | 0.412189485 | 0.412189485 | 0 | 0.017189373 | 0.261030661 |

| | I14 | 1.344 | 0.896 | 1.344 | 0 | 0.200704 | 0.200704 | 0 | 0 | 0.200704 |

| SDG07 | I15 | 1.74 | 1.16 | 1.74 | 0 | 0.3364 | 0.3364 | 0 | 0 | 0.3364 |

| | I16 | 0.792 | 0.528 | 0.792 | 0 | 0.069696 | 0.069696 | 0 | 0 | 0.069696 |

| | I17 | 0.186114072 | 0 | 0.207821153 | 0.000471197 | 0.034638448 | 0.043189632 | 0 | 0 | 0.043189632 |

| SDG09 | I18 | 1.187187839 | 0 | 1.137720229 | 0 | 1.409414964 | 1.409414964 | 0 | 0.002447044 | 1.294407318 |

| SDG10 | I19 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| SDG11 | I20 | 1.395 | 0.58125 | 1.395 | 0 | 0.662189063 | 0.662189063 | 0 | 0 | 0.662189063 |

| | I21 | 1.605 | 1.07 | 0.535 | 0 | 1.1449 | 0.286225 | 0.286225 | 1.1449 | 0 |

| SDG12 | I22 | 0.873 | 0.582 | 0.291 | 0 | 0.338724 | 0.084681 | 0.084681 | 0.338724 | 0 |

| | I23 | 1.266 | 0.844 | 1.266 | 0 | 0.178084 | 0.178084 | 0 | 0 | 0.178084 |

| | I24 | 0 | 0.271884075 | 0 | 0.07392095 | 0 | 0 | 0.07392095 | 0.07392095 | 0 |

| SDG13 | I25 | 1.767 | 0.14725 | 1.178 | 0 | 2.623590063 | 2.623590063 | 0 | 0.346921 | 1.062445563 |

| | I26 | 1.233 | 0.822 | 0.411 | 0 | 0.675684 | 0.168921 | 0.168921 | 0.675684 | 0 |

| SDG14 | I27 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| SDG15 | I28 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SDG16 | I29 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SDG17 | I30 | 0.27879153 | 0 | 0.229481436 | 0 | 0.077724717 | 0.077724717 | 0 | 0.002431485 | 0.052661729 |

| | I31 | 0.966 | 0.4025 | 0.322 | 0 | 0.414736 | 0.31753225 | 0.00648025 | 0.414736 | 0 |

| | I32 | 0.54 | 0.225 | 0.54 | 0 | 0.099225 | 0.099225 | 0 | 0 | 0.099225 |

| | I33 | 0.342 | 0.228 | 0.114 | 0 | 0.051984 | 0.012996 | 0.012996 | 0.051984 | 0 |

| | I34 | 0.429 | 0.286 | 0.429 | 0 | 0.020449 | 0.020449 | 0 | 0 | 0.020449 |

| | | | | | 0.119848838 | 28.14662694 | 20.20011023 | 2.663936762 | 13.88738285 | 11.80254046 |

| | | | | | 0.346191909 | 5.305339475 | 4.494453274 | 1.632157089 | 3.726577901 | 3.435482565 |

| = /( + ) | | | | | 0.938743699 | | 0.266404585 | | 0.479677962 |

7. Discussion of Simulation Results

The simulation involving three fictional universities provided important insights into the application of the MUDEIS framework and its ability to assess diverse institutional approaches toward sustainable development.

Simulated University 1, a newly established institution in a geographically isolated region, was selected to demonstrate strong sustainability efforts despite facing logistical challenges. These challenges primarily involved scaling operations and maintaining infrastructure across dispersed island campuses. In this simulation, out of the 34 assessed indicators, 19 showed improvement, particularly in areas such as poverty alleviation, quality education, energy efficiency, and strategic partnerships. Additionally, 14 indicators maintained their maximum scores, reflecting sustained performance. However, the indicator for recycling (I24) exhibited simulated regression, underscoring the need for enhanced waste-management strategies within the institution’s sustainability planning.

The TOPSIS analysis provided a quantitative perspective on universities’ relative performance in aligning with the SDGs for 2023 and 2024. In 2023, a moderate score of 0.57 reflected the university’s initial position despite its unique challenges. By 2024, the score rose significantly to 0.94, highlighting the effectiveness of its strategies, strong leadership in sustainability, and improved outcomes across multiple SDGs. This upward trajectory, further supported by the growth in student enrollment (from 1750 to 1920) and students completing a degree (from 1225 to 1978), underscored the university’s potential to serve as a model for sustainable development in remote and resource-constrained contexts. This increase in the similarity index (0.57 → 0.94) is directly linked to improvements in 19 indicators, particularly those associated with SDG 1 (Poverty Alleviation), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). Substantial gains in student completion rates, energy-efficiency adoption, and strengthened partnerships contributed most strongly to the improvement, while only one indicator (I24 Recycling) showed regression.

Simulated University 2, a well-established institution with a specialized academic focus, demonstrated partial alignment with the SDGs. While the simulation projected strong performance in specific areas, it also positioned the university to face challenges in sustaining consistent progress across a broader range of indicators. TOPSIS analysis offered further insights into its performance. In 2023, the university achieved the highest score of 0.72, reflecting strengths in specific SDGs, bolstered by its centralized location and specialized focus. However, in our simulation, a steep decline to 0.27 in 2024 highlighted significant challenges in maintaining consistent progress. This simulated decline was attributed to regression in critical areas, such as resource management, accessibility, and the impact of outdated policies. Notably, a decrease in female senior academics (from 43 to 34) negatively impacted its performance in SDG 5 (Gender Equality). To reverse this trend, institutions like University 2 would need to implement targeted strategies, modernize policy frameworks, and prioritize inclusive innovation to rebuild momentum and enhance their long-term sustainability impact. The simulated drop in the similarity index (0.72 → 0.27) is explained by declines in several high-weight indicators, most notably SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The reduction in female senior academics (from 43 to 34) significantly lowered the score for SDG 5, while regression in accessibility and resource management indicators further pulled the value downward.

Simulated University 3, a large and well-established institution with a broad academic scope, demonstrated notable progress in aligning with the SDGs by leveraging its diverse offerings and growing campus population. The TOPSIS analysis offered additional insights into a university’s SDG performance. In 2023, a low score of 0.30 highlighted initial challenges in SDG alignment, likely due to the complexities associated with its multidisciplinary and expanding operational scale. By 2024, however, the university achieved a significant improvement reaching the score of 0.48 which reflected the successful implementation of more comprehensive sustainability strategies, although room for further advancement remained. These gains were supported by the simulated increase in student enrollment (from 5500 to 6320) and campus population (from 26,180 to 27,950) indicating effective resource allocation and strategic planning. Moving forward a continued focus on addressing existing gaps, fostering institutional innovation and promoting integrated sustainability initiatives will be essential for University 3 to solidify its leadership and drive further progress across the full range of SDGs. The improvement in the similarity index (0.30 → 0.48) reflects positive shifts in energy efficiency (SDG 7), decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), and infrastructure expansion. Increases in student enrollment, campus population, and academic staffing, combined with more comprehensive sustainability initiatives, contributed measurably to the upward trend.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the robustness of the MUDEIS rankings. When all AHP-derived SDG weights were perturbed by ±10%, the ranking order of the three universities remained unchanged, indicating that the framework is moderately robust to variations in expert judgments. An additional equal-weights scenario produced slightly narrower score differences but again preserved the same ranking order. These results show that MUDEIS is not overly sensitive to reasonable fluctuations in criterion weights.

The present validation is based on simulated institutional profiles due to limited access to complete, standardized SDG datasets from real universities. Although simulation allows controlled stress-testing of MUDEIS under diverse conditions, it cannot substitute for empirical validation. This limitation of external validity is therefore explicitly acknowledged.

A real-data pilot study is planned for future work in order to assess the real-world transferability of MUDEIS, improve indicator calibration, and strengthen empirical grounding. Once access to verified institutional datasets becomes available, full statistical validation procedures, including confidence-interval estimation, will also be implemented.

The simulated values used in this study were generated through proportional scaling of commonly reported HEI metrics (student enrolment, academic staff, sustainability-related policies, and infrastructure), informed by publicly available sustainability reports and adjusted using plausible annual variation (±5–10%).

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the sensitivity-analysis results. In both the ±10% perturbation test and the equal-weights scenario, no rank reversals were observed, demonstrating that MUDEIS yields stable outputs under moderate changes in criterion weights.

To further assess the robustness of the MUDEIS results, a methodological comparison was performed using the AHP–SAW model, which functions as the linear additive counterpart of the Weighted Sum Model (WSM). Because SAW and WSM share the same aggregation logic, summing weighted normalized indicator values, the AHP–SAW configuration provides an appropriate baseline against which to evaluate the stability of the MUDEIS (AHP–TOPSIS) rankings.

The comparison showed that the ranking of the three universities remained identical under both MUDEIS and AHP–SAW, despite minor differences in the magnitude of composite scores. No rank reversals occurred in either year. This consistency demonstrates that institutional ordering is not an artifact of the TOPSIS distance-based formulation and that MUDEIS preserves rank stability even when a simpler MCDM method is used. The full numerical results, including SAW normalization matrices, weighted sums, and the cross-method comparison table, are provided in the public repository Link.

The structured simulation further demonstrated how the MUDEIS framework can be used even when real institutional data are limited or unavailable. By simulating diverse institutional characteristics, the framework enabled stress-testing, benchmarking, and forecasting in a range of scenarios. This capacity was valuable for both methodological development and institutional planning.

Due to data-access restrictions, the present validation employed simulated institutional profiles to stress-test MUDEIS. This approach enabled the examination of the model under controlled and intentionally extreme conditions. For example, the simulated decline of University 2 from a TOPSIS similarity score of 0.72 to 0.27 allowed us to evaluate MUDEIS’s ability to detect and interpret sharp regressions in sustainability performance. While useful for methodological demonstration, simulated results do not replace empirical validation. Future studies will focus on applying MUDEIS to actual HEI datasets in order to assess real-world transferability, refine indicator calibration, and strengthen the framework’s generalizability. Because the dataset is simulated, statistical confidence intervals were not computed. These will be incorporated once real HEI performance datasets are available.

In the simulation, all universities highlighted the importance of targeted policies, continuous improvement, and innovative strategies for achieving SDG goals. By addressing the gaps in equity, resource management, and governance, each institution could enhance its sustainability contributions.

To support interpretability, MUDEIS allows changes in the TOPSIS similarity index () to be decomposed into indicator-level contributions. For example, the simulated decline of University 2 from 0.72 (2023) to 0.27 (2024) was primarily driven by regressions in SDG 5 (female senior academics), SDG 3 (well-being), and SDG 11 (accessibility and space utilization). This decomposition clarifies which indicators exert the largest influence on ranking shifts and enables HEIs to identify targeted areas for intervention. Future real-data applications will include graphical contribution maps to further enhance transparency and diagnostic value.

A comparison of these universities revealed several trends, offering insights into the diverse approaches of HEIs in aligning with the SDGs. Larger, established universities with broader academic scopes, such as University 3, demonstrated a stronger capacity to address diverse SDGs owing to their scale and resource availability. In contrast, smaller or specialized institutions such as University 1 and University 2, showed a deeper alignment with specific goals but encountered challenges when integrating a broader range of SDGs into their operations.

A common thread across all institutions was the prioritization of SDG 4, which reflected the core mission of HEIs to provide quality education. However, contributions to environmental and equity-related goals, such as SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) varied significantly.

Geographic and contextual factors can influence HEIs’ approaches to sustainability. Tailored policies and partnerships are essential in overcoming barriers especially in remote areas where collaboration with external organizations and investment in innovative solutions bridge resource gaps and enhance sustainability efforts.

The integration of advanced analytics provides another avenue for further progress. By using data-driven approaches to monitor performance and optimize resource allocation, all universities can enhance their sustainability initiatives. This technology-driven perspective not only can improve operational efficiency but also ensures that institutions remain adaptive and responsive to evolving sustainability demands.

The prioritization of SDG 4 (Quality Education) as the highest-weighted goal aligns with HEIs’ primary mission of education and knowledge dissemination. This emphasis highlights the transformative potential of quality education to address societal challenges, foster innovation, and equip future generations with the skills necessary to navigate complex global issues. Beyond its immediate impact, quality education generates cross-cutting benefits that extend to reducing inequalities SDG 10 and promoting decent work and economic growth in SDG 8. These interconnected outcomes reinforce its pivotal role in advancing sustainability and underscore why HEIs prioritize it as a foundational goal.

Medium-priority goals, such as SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), emphasize the responsibility of HEIs to foster inclusivity and equity. Policies such as inclusive hiring practices, family friendly initiatives, and support programs for marginalized groups are essential tools for addressing these goals. In addition to these social dimensions, HEIs also contribute to environmental sustainability through goals such as SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). Adopting resource-efficient practices and developing green infrastructure enable institutions to align their operations with global sustainability objectives while addressing pressing environmental challenges.

While medium-priority goals show significant progress, lower-priority SDGs, such as SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water), reveal areas where HEIs’ contributions are less pronounced. Although less directly relevant to institutional operations, these goals present opportunities for integration through interdisciplinary research and strategic partnerships. Collaboration with environmental organizations and community engagement initiatives provides pathways to effectively address these goals. For instance, targeted programs that focus on marine ecosystem health or biodiversity conservation can create meaningful impacts and foster a balanced approach to sustainability.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

The framework underscores the critical role of HEIs in aligning their operations, research, and teaching strategies with SDGs. By systematically evaluating the priority weights assigned to various SDGs and implementing the proposed MCDM/A framework, this study provides actionable insights into how HEIs can strategically enhance their sustainability efforts. These insights form the basis for exploring the broader implications of these findings, the strengths and limitations of the proposed framework, and the potential directions for future research. In view of the above, a new approach is introduced to evaluate how HEIs integrate the SDGs.

This study highlights the potential of structured, data-driven frameworks for guiding HEIs toward enhanced sustainability through strategic alignment with the SDGs. By prioritizing high-impact goals and addressing key areas for improvement, universities can maximize their contributions to global sustainability efforts while fulfilling their core missions. The proposed framework provides a valuable tool for institutions seeking to navigate the complexities of sustainability evaluation and serves as a roadmap for continuous improvement and meaningful progress.

The MUDEIS framework was built on MCDM/A and combined AHP and TOPSIS in a complementary manner. Given that achieving SDGs requires the coordination of diverse resources, relying solely on a single dimension, such as environmental factors, is insufficient to address the complex, multidimensional nature of sustainable development.

Among the various MCDM/A approaches, TOPSIS is widely recognized for its ability to evaluate multiple, often conflicting criteria simultaneously, providing a balanced and objective assessment of sustainability performance [

33]. However, effective decision-making also requires an accurate determination of criteria weights, as their relative importance may vary across different contexts. To address this, AHP is incorporated into MUDEIS to derive these weights, leveraging expert judgments to refine the evaluation process. By integrating AHP and TOPSIS, the framework ensures a comprehensive, structured, and context-sensitive sustainability assessment of HEIs.

The MUDEIS framework for sustainability assessment offers several advantages that enhance the decision-making processes. MUDEIS incorporates both qualitative and quantitative criteria, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation to identify the optimal solutions. By incorporating expert-derived criteria, it leverages specialized knowledge to establish robust benchmarks, thereby improving the relevance and depth of sustainability evaluations. Although expert input is valuable, it may introduce bias; however, MUDEIS mitigates this by applying quantitative methods to evaluate alternatives against ideal solutions, ensuring a more objective assessment. The structured nature of MUDEIS provides a transparent and systematic methodology for decision-making, rendering each step, from criteria weighting to final rankings, clear and understandable. Additionally, the MUDEIS framework facilitates trade-off analysis by allowing decision-makers to compare alternatives with an ideal solution, making it easier to assess competing sustainability objectives and identify the best possible compromise. By integrating expert-derived criteria with systematic and objective methodologies, HEI can conduct more reliable and comprehensive sustainability assessments, leading to informed and balanced decision-making.

Despite its strengths, the MUDEIS framework has several limitations. The reliance on expert judgments, while valuable for ensuring informed decision-making, inevitably introduces a degree of subjectivity that may influence the prioritization of specific SDGs. To enhance the representativeness and inclusivity of sustainability evaluations, expanding stakeholder participation to incorporate insights from students, policymakers, and community members would be beneficial.

A further step in mitigating subjectivity would be the integration of participatory governance models, which provide a structured approach to balancing expert perspectives with diverse stakeholder input. By actively involving students, faculty, policymakers, and local communities in the evaluation process, these models can foster a more democratic, transparent, and context-sensitive approach to sustainability assessment, ensuring that decisions reflect a broader range of experiences and priorities.

Additionally, data reliability and availability remain challenging, particularly for institutions with limited reporting mechanisms. Improving data transparency and accessibility is essential for accurate assessments. Rather than viewing data limitations as an inherent constraint, the discussion could expand on how institutions can proactively overcome these barriers through digital innovations, institutional collaborations, and policy incentives.

The MUDEIS framework not only evaluates current sustainability practices but also has the potential to track long-term impacts, making it a valuable tool for monitoring institutional progress over time. However, sustainability priorities are not static: they evolve in response to climate change, technological advancements, policy shifts, and institutional objectives. To ensure that MUDEIS remains responsive to these changing priorities, future research should focus on developing dynamic evaluation models that can adapt to these shifts.

One way to enhance MUDEIS’ adaptability is to integrate machine learning and big data analytics, which could enable real-time adjustments to sustainability criteria based on continuously updated data. This technological enhancement would not only improve the accuracy and efficiency of evaluations but also allow institutions to proactively respond to emerging sustainability challenges, such as digital inclusion, climate resilience, and global health crises. Therefore, we plan to enhance our framework with machine learning and big data analytics.

Although MUDEIS incorporates quantitative methods to enhance objectivity, sustainability assessment also involves complex trade-offs that require a human-centered perspective. Future discussions could explore how qualitative deliberative methods, such as scenario-based decision-making, stakeholder deliberation forums, and ethical impact assessments, could complement trade-off analysis. These approaches would ensure that sustainability decisions are not only data-driven but also ethically and socially informed.

Future development of MUDEIS will incorporate machine-learning and big-data capabilities to enhance predictive accuracy, automate weight adaptation, and support real-time sustainability monitoring. Data sources will include institutional SDG dashboards, annual sustainability reports, learning management systems (LMS), administrative datasets (e.g., enrolment, energy use, research outputs), and publicly available open-data repositories (e.g., Eurostat, UNESCO, OECD).

Updates are planned on a semi-annual basis, enabling the platform to incorporate newly released institutional and national sustainability data. A structured governance protocol will be implemented, including data-quality checks, version control of SDG indicators, traceability of weight updates, and a transparent log of methodological adjustments.

The integration pipeline will follow three stages: (i) data ingestion and cleaning from multiple validated sources; (ii) dynamic weighting using supervised models trained on historical data and expert inputs; and (iii) continuous model evaluation through back-testing against real HEI performance. This roadmap ensures that MUDEIS remains methodologically robust, transparent, and adaptable as higher-education sustainability datasets expand.