Human-in-the-Loop AI Use in Ongoing Process Verification in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- •

- •

- •

3. State of the Art: Towards the Augmented OPV

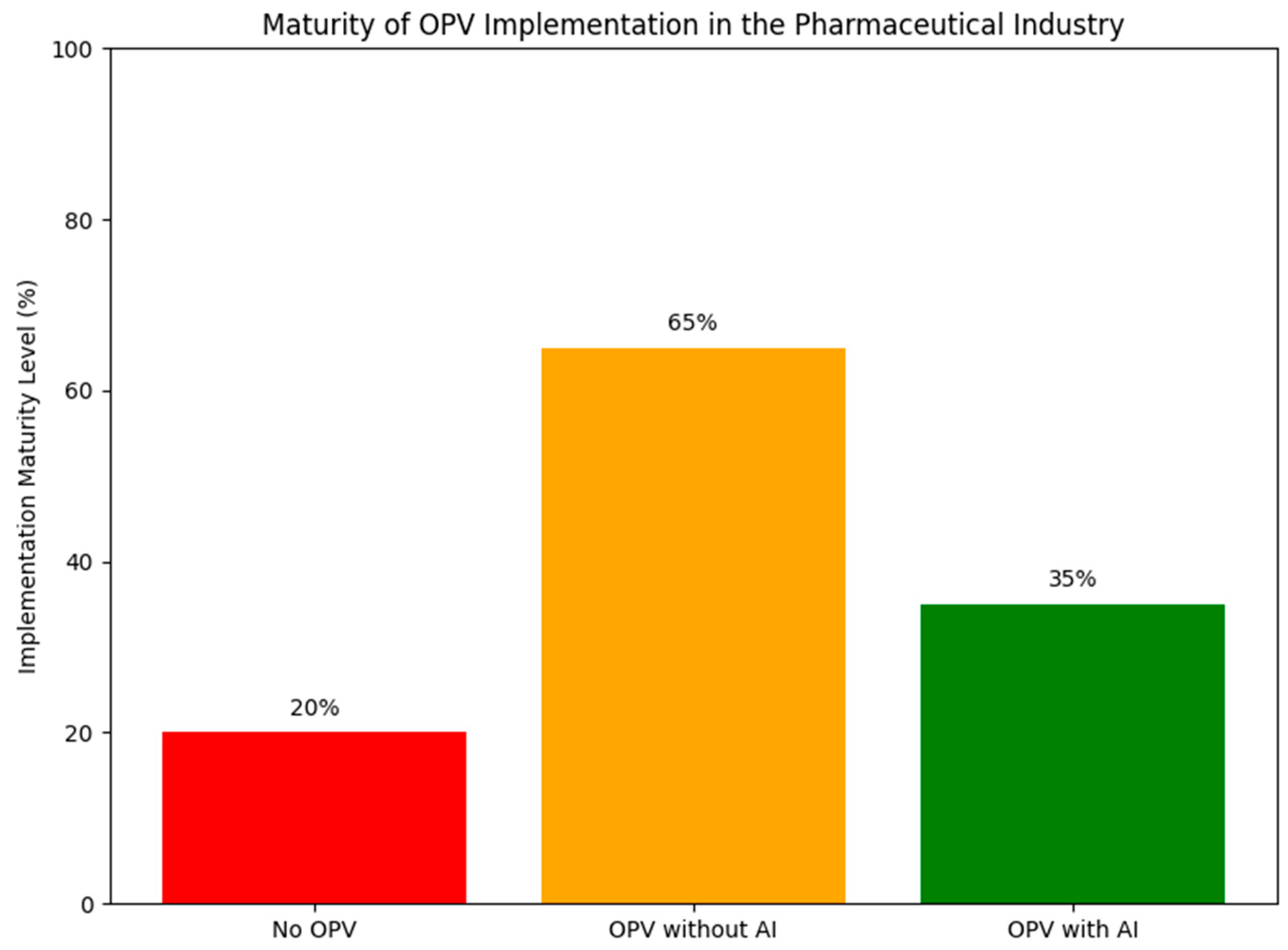

3.1. Implementation Maturity Level

3.2. Current Applications for AI in Pharmaceutical OPV

3.2.1. Real-Time Process Monitoring

3.2.2. Predictive Maintenance

3.2.3. Automated Visual Inspection

3.2.4. Deviation Analysis and CAPA Optimization

3.2.5. Digital Twins and Process Simulation

3.2.6. Data Integration and Knowledge Management

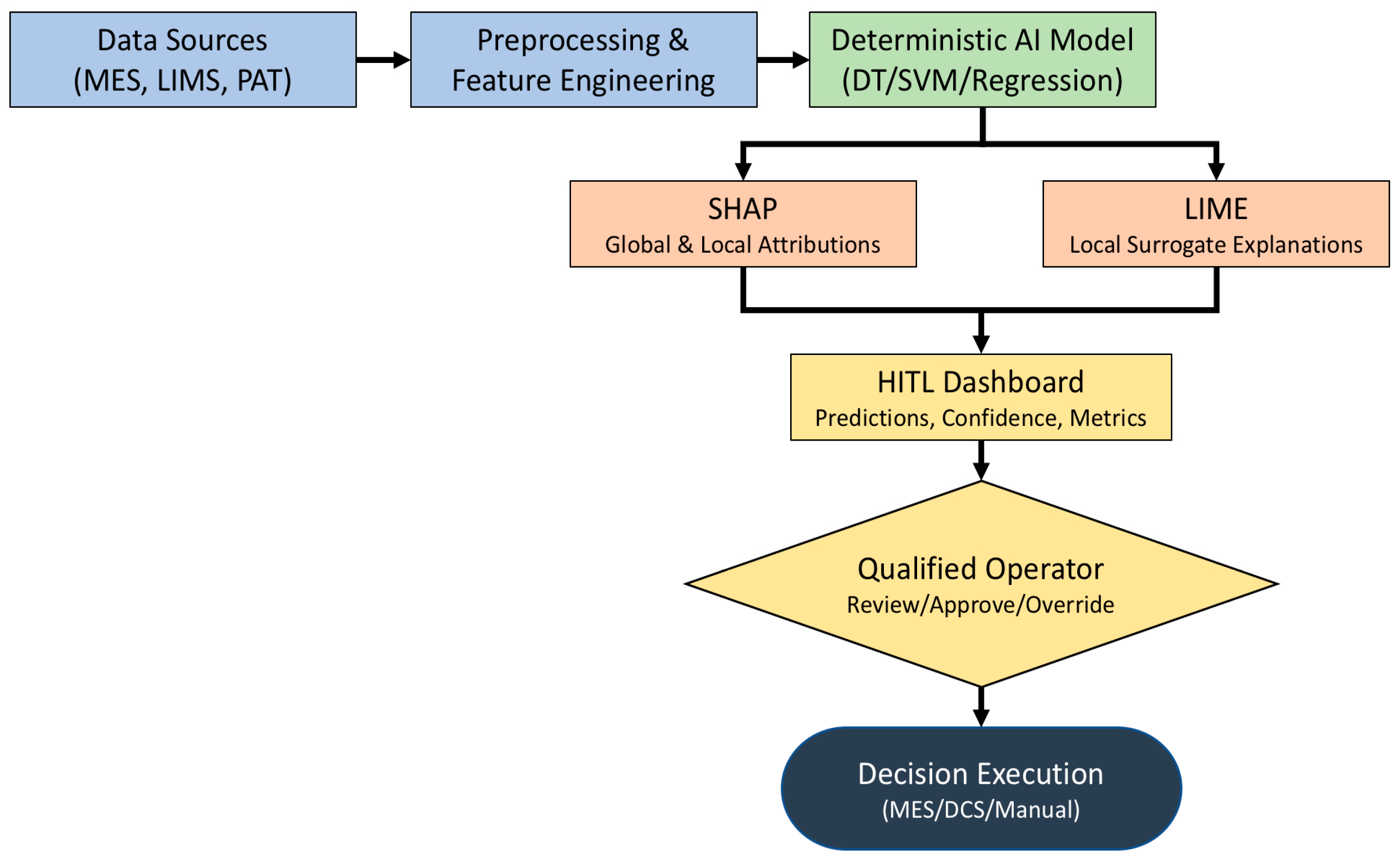

4. HITL Architecture Overview

4.1. Distinguishing HITL AI from Classical Decision-Support Systems

4.2. Architectural Layers

- •

- Data Acquisition Layer: Collects real-time process data from sensors, manufacturing execution systems (MESs), and laboratory information management systems (LIMSs). This layer ensures data integrity and traceability, complying with ALCOA+ principles.

- •

- Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Layer: Cleans, normalizes, and transforms raw data into structured inputs for AI models. Feature selection is often guided by domain experts to ensure relevance and interpretability.

- •

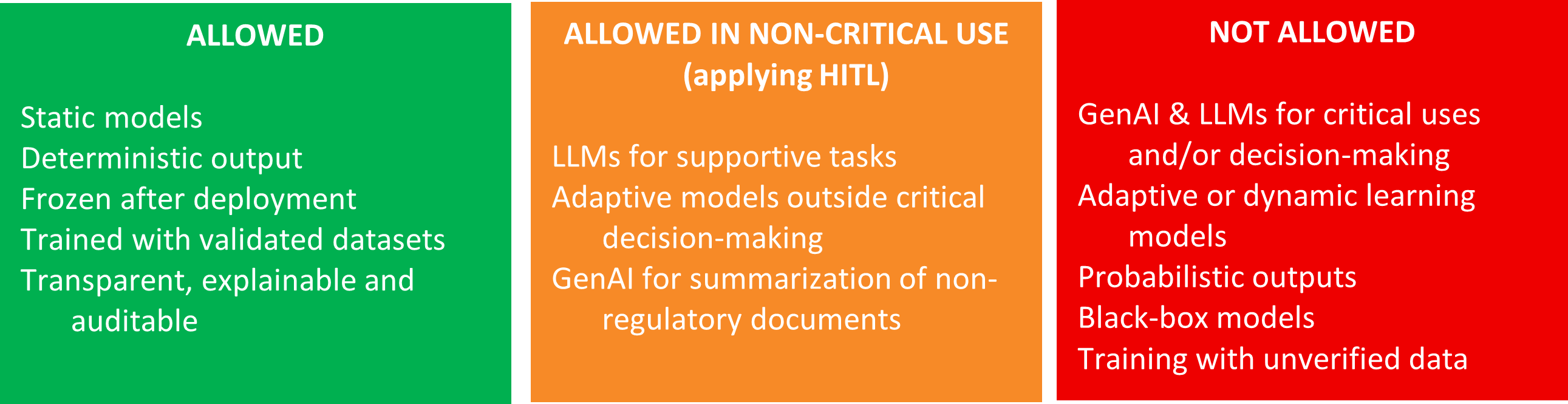

- AI Model Layer: Hosts deterministic models such as decision trees, support vector machines, or rule-based systems. These models are trained on historical data and validated against predefined acceptance criteria. Self-adaptive models are excluded per Annex 22.

- •

- Human Oversight Layer: Provides interfaces for human operators to review, validate, and override AI outputs. This layer includes dashboards, alerts, and explainability tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) that justify model decisions and display confidence scores.

- •

- Decision Execution Layer: Implements approved decisions into the manufacturing process, either manually or via automated control systems. All actions are logged and auditable.

4.3. Interaction Modes

- •

- Supervisory Mode: AI provides recommendations, and humans make final decisions. Common in batch release and deviation management.

- •

- Collaborative Mode: AI and humans jointly analyze data, with humans validating AI-generated insights. Used in root cause analysis and trend detection.

- •

- Override Mode: Humans can reject or modify AI outputs based on contextual knowledge or regulatory constraints. Essential for compliance with Annex 22.

4.4. Explainability and Transparency

- •

- SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations): Quantifies the contribution of each feature to a prediction.

- •

- LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Generates local approximations of model behavior.

4.5. Governance and Lifecycle Management

5. Regulatory Challenges in AI-Driven OPV

| Aspect | FDA (U.S.) | EMA (EU/EFTA) | WHO/International |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Nature and Scope | Non-binding, risk-based guidance (e.g., 2023 SaMD Action Plan [19], 2025 AI-in-drug draft guidance [6]) | EU-centered, risk-tiered framework under MDR/IVDR; EMA reflection papers (Sept 2024) align with EU AI Act [42,43] Implemented via network-wide plan 2023–2028 [42] | Advisory, principle-based (safety, transparency) for LMICs; fosters global harmonization [44] |

| Lifecycle Governance | Emphasizes Change Control Plans (e.g., PCCP), real-world evidence, and post-market monitoring [6,19] | Reflection Paper specifies governance over drug discovery, clinical trials, post-market, data integrity, GxP compliance; MDR/IVDR uses EN 62304 lifecycle standards [42,45] | WHO recommends documentation of study design, human oversight, lifecycle validation consistent with other national frameworks [44] |

| Core Focus Areas | Contextual credibility, interpretability, and traceability of adaptive systems [15,40] | Risk-based model (“high-patient risk” vs. “high-regulatory impact”); includes bias control, explainability, and human oversight; also issues QO for AI-based diagnostics (AIM-NASH) [21,22,42] | Emphasizes oversight alignment with EU, FDA, data protection, cybersecurity, and equitable access [44] |

| Structure and Certainty | Flexible, dialog-based case-by-case approval; fosters innovation but increases unpredictability [6,19] | Structured, tiered, and formal; clarifies compliance thresholds at each lifecycle stage [42,43] | Promotes harmonization but leaves implementation to national authorities; encourages regulatory sandboxes [44] |

| Alignment Efforts | Invites public comments, collaborates under NIST AI Risk Management Framework [6,19] | Harmonized across EU via HMA–EMA workplan; EU AI Act compliance begins 2024 [42,43] | Supports cross-border standardization via EU–US, HMA, and global forums [44] |

| Industry Impact | US–EU approval divergence complicates global submission; flexible FDA promotes early collaboration [6,19] | EU’s predictability may slow early adoption but ensures stricter validation and clarity [42,43] | Convergence on risk-based principles, divergence on implementation [44] |

5.1. Scope and Model Restrictions

5.2. HITL Requirements

5.3. Validation and Performance Criteria

5.4. Proposal for Deterministic Behavior Verification in AI Models: A Suitability-Inspired Testing Framework

- Controlled Input Repetition: Repeated execution of the model using identical input data and fixed system parameters (e.g., hardware, software versions, and random seed initialization) to detect any output variability.

- Environmental Stability Assessment: Evaluation of model behavior across different but nominally equivalent computational environments (e.g., containerized deployments, virtual machines) to identify hidden dependencies or non-deterministic execution paths.

- Tolerance Threshold Definition: Establishment of acceptable output deviation margins, if applicable, particularly for models involving floating-point operations or probabilistic components. These thresholds must be justified based on domain-specific requirements.

- Logging and Traceability: Comprehensive logging of execution metadata, including system states, library versions, and runtime configurations, to facilitate reproducibility and forensic analysis in case of discrepancies.

- Benchmarking Against Reference Outputs: Comparison of current model outputs with a validated reference set to detect regressions or unintended behavioral shifts.

5.5. Data Integrity and Independence

5.6. Explainability and Confidence Scores

5.7. Operational Oversight

6. Governance Best Practices for HITL AI in GMP Environments

6.1. Multidisciplinary Oversight

- •

- Quality Assurance;

- •

- Information Technology;

- •

- Mathematics, Statistics, Data Scientists, and AI specialists;

- •

- Regulatory Affairs;

- •

- Process Engineering.

6.2. Role Definition and Accountability

- •

- Model development and validation;

- •

- Human oversight and decision review;

- •

- Data management and integrity;

- •

- Change control and lifecycle monitoring.

6.3. Lifecycle Management

- •

- Design and Development: Models must be built using GMP-compliant data and documented methodologies.

- •

- Validation: Performance must be benchmarked against predefined acceptance criteria.

- •

- Deployment: HITL interfaces must be tested for usability and reliability.

- •

- Monitoring: Ongoing performance reviews and input space validation are required.

- •

- Retirement: Decommissioning must follow formal procedures to prevent unintended use.

6.4. Documentation and Auditability

- •

- Model predictions and confidence scores;

- •

- Human decisions and overrides;

- •

- System updates and retraining events.

6.5. Risk Management

- •

- Impact of incorrect predictions;

- •

- Reliability of human oversight;

- •

- Data integrity vulnerabilities;

- •

- Regulatory non-compliance scenarios.

6.6. Ethical AI Principles

7. Case Studies on HITL AI in Pharmaceutical OPV

7.1. Case Study A: Real-Time Monitoring of Granulation Process

- •

- Outcome: Improved batch consistency and reduced deviations.

- •

- Governance: QA reviewed model outputs daily; override capability was retained.

- •

- Compliance: Model validated under Annex 22 [8]; deterministic behavior ensured.

7.2. Case Study B: Predictive Maintenance in Sterile Filling

- •

- Outcome: Reduced downtime and improved equipment reliability.

- •

- Governance: Engineering and QA jointly managed model performance.

- •

- Compliance: AI used in non-critical support role; HITL ensured no direct impact on product quality.

7.3. Case Study C: Deviation Root Cause Analysis

- •

- Outcome: Accelerated investigations and improved CAPA effectiveness.

- •

- Governance: Regulatory Affairs ensured traceability of decisions.

- •

- Compliance: AI outputs were advisory; human judgment remained primary.

7.4. Summary of Cases A, B, and C

8. Implementation Framework for HITL AI in Ongoing Process Verification

- Phase I: Feasibility and Risk Assessment

- Process Selection: Identify OPV processes suitable for AI augmentation (e.g., granulation, blending, and filling).

- Risk Analysis: Apply ICH Q9 principles to assess risks associated with AI deployment.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Involve QA, IT, regulatory, and operations teams early in the planning.

- Phase II: Model Development and Validation

- Data Preparation: Ensure data integrity, traceability, and representativeness.

- Model Design: Use deterministic algorithms (e.g., decision trees, regression models) compliant with Annex 22 [8].

- Explainability Integration: Embed SHAP or LIME for model transparency.

- Phase III: HITL Interface Design

- User Interface: Develop dashboards for human review of AI outputs.

- Override Mechanism: Implement controls for human intervention and decision logging.

- Training Programs: Educate operators on AI behavior, limitations, and responsibilities.

- Phase IV: Deployment and Monitoring

- Change Control: Document deployment procedures and approval workflows.

- Performance Monitoring: Track model accuracy, confidence scores, and override frequency.

- Audit Readiness: Maintain complete documentation and audit trails.

- Phase V: Continuous Improvement

- Feedback Loops: Use human feedback to refine model inputs and oversight protocols.

- Periodic Review: Reassess model performance and compliance annually or upon process changes.

- Scalability Planning: Evaluate potential for broader application across manufacturing sites.

9. Advantages and Limitations of AI in Ongoing Process Verification Under the Human-in-the-Loop Paradigm

9.1. Advantages

- Enhanced Data Processing and Pattern Recognition: AI algorithms can process large volumes of process data in real time, identifying subtle trends, deviations, or anomalies that may elude traditional statistical methods or human observation. This capability supports early detection of process drift and facilitates proactive interventions [34].

- Continuous Monitoring and Adaptability: Unlike static control systems, AI models can adapt to evolving process conditions, enabling dynamic verification strategies. This is particularly valuable in complex or multivariate manufacturing environments where process variability is inherent [34].

- Decision Support and Risk Mitigation: In an HITL configuration, AI serves as a decision-support tool, providing probabilistic assessments or predictive insights that inform human judgment. This reduces cognitive load and enhances the consistency of decision-making while preserving human oversight in critical scenarios [31].

- Auditability and Traceability: When properly governed, AI systems can generate detailed logs of their outputs and interactions with human operators, contributing to regulatory compliance and facilitating retrospective analysis [38].

9.2. Limitations

- Human Factors and Operational Burden: While HITL mitigates the risks of full automation, it introduces challenges related to human engagement, such as alert fatigue, over-reliance on AI outputs, or inconsistent intervention practices. Ensuring that human operators remain effectively integrated and trained is essential [8,31].

10. Conclusions and Future Outlook

- •

- Standardization of Validation Protocols: Industry-wide benchmarks for AI performance and explainability will emerge.

- •

- Integration with Advanced Analytics: HITL systems will be combined with multivariate analysis, digital twins, and real-time release testing.

- •

- Expansion Beyond OPV: Applications will extend to deviation management, CAPA effectiveness, and regulatory intelligence.

- •

- Global Regulatory Harmonization: Other regulatory bodies may adopt similar frameworks, fostering international consistency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CAPA | Corrective and Preventive Action |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CPPs | Critical Process Parameters |

| CQAs | Critical Quality Attributes |

| EU GMP | European Union Good Manufacturing Practices |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonization |

| ISPE | International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LIMS | Laboratory Information Management Systems |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| MES | Manufacturing Execution Systems |

| OPV | Ongoing Process Verification |

| PAT | Process Analytical Technology |

| QA | Quality Assurance |

| QRM | Quality Risk Management |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SOPs | Standard Operating Procedures |

| USP | United States Pharmacopeia |

| DCS | Distributed Control System |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

Appendix A

References

- Phiri, V.J.; Battas, I.; Semmar, A.; Medromi, H.; Moutaouakkil, F. Towards enterprise-wide Pharma 4.0 adoption. Sci. Afr. 2025, 28, e02771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destro, F.; Inguva, P.K.; Srisuma, P.; Braatz, R.D. Advanced methodologies for model-based optimization and control of pharmaceutical processes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2024, 45, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.J.; Patel, A.K. Digital transformation and Industry 4.0 in pharma manufacturing: The role of IoT, AI, and big data. J. Integral Sci. 2024, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Q8(R2) Pharmaceutical Development. 2009. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q8-r2-pharmaceutical-development (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- ICH. Q14 Analytical Procedure Development. 2023. Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_Q14_Guideline_2023_1116.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. PAT—A Framework for Innovative Pharmaceutical Development, Manufacturing, and Quality Assurance. FDA. 2004. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/71012/download (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Manzano, T.; Whitford, W. Artificial Intelligence Empowering Process Analytical Technology and Continued Process Verification in Biotechnology. GEN Biotechnol. 2025, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Annex 22 Draft. EMA. 2025. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/5f38a92d-bb8e-4264-8898-ea076e926db6_en?filename=mp_vol4_chap4_annex22_consultation_guideline_en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Vora, L.; Gholap, A.; Jetha, K.; Thakur, R.; Solanki, H.; Chavda, V. Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodumuru, R.; Sarkar, S.; Parepally, V.; Chandarana, J. Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Integration in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: A Smart Synergy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huanbutta, K.; Burapapadh, K.; Kraisit, P.; Sriamornsak, P.; Ganokratana, T.; Suwanpitak, K.; Sangnim, T. The Artificial Intelligence-Driven Pharmaceutical Industry: A Paradigm Shift in Drug Discovery, Formulation Development, Manufacturing, Quality Control, and Post-Market Surveillance. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 203, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, S.; Fisher, A.; Tyner, K.; Yu, L.; Lee, S.; Kopcha, M. Industry 4.0 for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: Preparing for the Smart Factories of the Future. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 602, 120554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S. Regulatory Perspectives for AI/ML Implementation in Pharmaceutical GMP Environments. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huysentruyt, K.; Kjoersvik, O.; Dobracki, P.; Savage, E.; Mishalov, E.; Cherry, M.; Leonard, E.; Taylor, R.; Patel, B.; Abatemarco, D. Validating Intelligent Automation Systems in Pharmacovigilance: Insights from Good Manufacturing Practices. Drug Saf. 2021, 44, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muppalla, A.; Maddi, B.; Maddi, N. Artificial Intelligence in Regulatory Compliance: Transforming Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Documentation. Int. J. Drug Regul. Aff. 2025, 13, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, C.; Yerram, S.; Abishek, V.; Nizam, V.; Aglave, G.; Patnam, J.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Srivastava, S. Innovative Approaches in Regulatory Affairs: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Efficient Compliance and Decision-Making. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. EU GMP Annex 15: Qualification and Validation. 2015. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/2015-10_annex15_0.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- ISPE. Continued Process Verification in Stages 1–3. Pharmaceutical Engineering. 2020. Available online: https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering/july-august-2020/continued-process-verification-stages-1-3 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CDER’s Perspective on the Continuous Manufacturing Journey. FDA. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/173811/download (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Jeong, S.H.; Choi, D.H. Process Analytical Technology Tools for Monitoring Pharmaceutical Unit Operations: A Control Strategy for Continuous Process Verification. Pharmaceutics 2024, 13, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, C. Janssen Case Study Presentation—Continuous Process & Real-Time Release. PQRI. 2015. Available online: https://pqri.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/pdf/Sanchez.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Novartis. Towards Real-Time Release of Pharmaceutical Tablets. 2021. Available online: https://oak.novartis.com/44574/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Evans, C.; Giacoletti, K.; Hurley, D.; Levers, R.; McMenamin, M.; Wade, J. Process Validation in the Context of Small Molecule Drug Substance and Drug Product Continuous Manufacturing Processes. ISPE Concept Paper. 2024. Available online: https://ispe.org/sites/default/files/concept-papers/ISPE_PV_Context%20of%20Small%20Molecule%20DS-DP.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Pugatch Consilium. AI Readiness in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Final Report. Pugatch Consilium. 2024. Available online: https://www.pugatch-consilium.com/reports/AI_Readiness_in_the_Pharmaceutical_Industry_Final%20report.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Valloppillil, S. AI in Pharma: Startups, VCs and Big Tech Are Reshaping the Industry. Forbes. 2025. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sindhyavalloppillil/2025/07/17/ai-in-pharma-era-where-big-tech-leads-startups-scale-and-incumbents-strategize/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Buvailo, A. How the Pharmaceutical Industry Is Adopting Artificial Intelligence to Boost Drug Research. BioPharmaTrend. 2022. Available online: https://www.biopharmatrend.com/artificial-intelligence/how-pharmaceutical-industry-is-adopting-artificial-intelligence-to-boost-drug-research-496/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System. 2008. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q10-pharmaceutical-quality-system (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Process Validation: General Principles and Practices. FDA. 2011. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Process-Validation--General-Principles-and-Practices.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Eissa, M.E. Enhancing Sterile Manufacturing with AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Equipment Maintenance. Pharma Focus America. 2025. Available online: https://www.pharmafocusamerica.com/manufacturing/enhancing-sterile-manufacturing-with-ai (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Clayton, J. Real-Time In-Line Monitoring of High Shear Wet Granulation. American Pharmaceutical Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.americanpharmaceuticalreview.com/Featured-Articles/345587-Real-Time-In-Line-Monitoring-of-High-Shear-Wet-Granulation/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- BioPhorum. Implementing AI Systems in Regulated Pharma Environments. BioPhorum. 2025. Available online: https://www.biophorum.com/download/implementing-ai-systems-in-regulated-pharma-environments-biophorum/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Altabrisa Group. AI in Pharma Deviation Management: GMP Compliance & Automation. Altabrisa Group. 2025. Available online: https://altabrisagroup.com/ai-in-pharma-deviation-management-gmp-compliance-automation/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology. CPV of the Future—AI-Powered CPV for Bioreactor Processes. 2023. Available online: https://journal.pda.org/content/77/3/146 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Seeq Corporation. Realizing the Benefits of CPV with Advanced Analytics. White Paper. 2022. Available online: https://www.seeq.com/resources/downloads/realizing-the-benefits-of-cpv-with-advanced-analytics-2/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Mosqueira-Rey, E.; Hernández-Pereira, E.; Alonso-Ríos, D.; Bobes-Bascarán, J.; Fernández-Leal, Á. Human-in-the-loop Machine Learning: A State of the Art. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 3005–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadia, H. Rule-Based vs. LLM-Based AI Agents: A Side-by-Side Comparison. TeckNexus. 2025. Available online: https://tecknexus.com/rule-based-vs-llm-based-ai-agents-a-side-by-side-comparison/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Natarajan, S.; Mathur, S.; Sidheekh, S.; Stammer, W.; Kersting, K. Human-in-the-loop or AI-in-the-loop? Automate or Collaborate? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 28594–28600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISPE. GAMP 5: A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems, 2nd ed.; ISPE: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022; Available online: https://ispe.org/publications/guidance-documents/gamp-5-guide-2nd-edition (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- EFPIA. Application of AI in a GMP/Manufacturing Environment—An Industry Approach; Version 1.0, September 2024. Available online: https://www.efpia.eu/media/vqmfjjmv/position-paper-application-of-ai-in-a-gmp-manufacturing-environment-sept2024.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- European Commission. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/196377/AI%20HLEG_Ethics%20Guidelines%20for%20Trustworthy%20AI.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- PIC/S. PI 041-1: Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments. 2021. Available online: https://picscheme.org/docview/4234 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Medicinal Product Lifecycle. EMA. 2024. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/system/files/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-use-artificial-intelligence-ai-medicinal-product-lifecycle-en.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- European Union. Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- WHO. TRS 1033, Annex 4: Guideline on Data Integrity. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/annex-4-trs-1033 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management—Scientific Guideline; EMA/CHMP/ICH/24235/2006 Corr.2. 2006. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q9-quality-risk-management-scientific-guideline (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ECA Academy. What Is ‘Human-in-the-Loop’? GMP-Compliance News, 8 September de 2025. Available online: https://www.gmp-compliance.org/gmp-news/what-is-human-in-the-loop (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP). General Chapter 1058: Analytical Instrument Qualification. USP–NF.; Rockville, MD, USA. Available online: https://online.uspnf.com/uspnf/document/1_GUID-EA8F36CE-5B60-4CA4-A3B8-51F22DE87BC6_1_en-US (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- FDA/ICH. Q2(R2)/Q14 Overview Deck. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/177718/download (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ueda, D.; Kakinuma, T.; Fujita, S.; Kamagata, K.; Fushimi, Y.; Ito, R.; Matsui, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Nakaura, T.; Fujima, N.; et al. Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Review and recommendations. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, J.; Citro, B.; Malpani, R.; Lippert, C.; Madai, V.I. A trustworthy AI reality-check: The lack of transparency of artificial intelligence products in healthcare. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1267290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Maturity Level | Description | Estimated Adoption | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| No OPV | Legacy systems without formal OPV frameworks | ~20% | Pugatch Consilium (2024) [24] |

| Traditional OPV | OPV based on statistical process control and retrospective data analysis | ~65% | ISPE (2020) [18] FDA (2011) [28] |

| AI-Enhanced OPV | OPV integrated with AI models for real-time monitoring and predictive analytics | ~35% (pilot or partial) | BioPharmaTrend (2025) [26], Pharma Focus America (2025) [29] |

| Metric | Recommended Threshold | Purpose | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | ≥95% | Overall correctness of predictions | Annex 22 EU-GMP ISPE GAMP 5 [8] |

| Precision | ≥90% | Minimizing false positives | Annex 22 EU-GMP [8] |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | ≥90% | Minimizing false negatives | Annex 22 EU-GMP [8] |

| F1 Score | ≥0.90 | Balanced measure for imbalanced datasets | Annex 22 EU-GMP BioPhorum [8] |

| Specificity | ≥95% | Correctly identifying true negatives | Annex 22 EU-GMP [8] |

| Explainability | SHAP or LIME integration | Transparency and interpretability | Annex 22 EU-GMP [8] |

| Case Study | Key Data/Impact/Benefit | References |

|---|---|---|

| A. Real-Time Monitoring of Granulation Process |

| [30] |

| B. Predictive Maintenance in Sterile Filling |

| [29] |

| C. Deviation Root Cause Analysis |

| [32] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Obon, M.; Rouaz-El-Hajoui, K.; Sancho-Ochoa, V.; Vargas, R.; Pérez-Lozano, P.; Suñé-Pou, M.; García-Montoya, E. Human-in-the-Loop AI Use in Ongoing Process Verification in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Information 2025, 16, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121082

Romero-Obon M, Rouaz-El-Hajoui K, Sancho-Ochoa V, Vargas R, Pérez-Lozano P, Suñé-Pou M, García-Montoya E. Human-in-the-Loop AI Use in Ongoing Process Verification in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Information. 2025; 16(12):1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121082

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Obon, Miquel, Khadija Rouaz-El-Hajoui, Virginia Sancho-Ochoa, Ronny Vargas, Pilar Pérez-Lozano, Marc Suñé-Pou, and Encarna García-Montoya. 2025. "Human-in-the-Loop AI Use in Ongoing Process Verification in the Pharmaceutical Industry" Information 16, no. 12: 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121082

APA StyleRomero-Obon, M., Rouaz-El-Hajoui, K., Sancho-Ochoa, V., Vargas, R., Pérez-Lozano, P., Suñé-Pou, M., & García-Montoya, E. (2025). Human-in-the-Loop AI Use in Ongoing Process Verification in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Information, 16(12), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121082