Machine Learning-Enhanced Architecture Model for Integrated and FHIR-Based Health Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

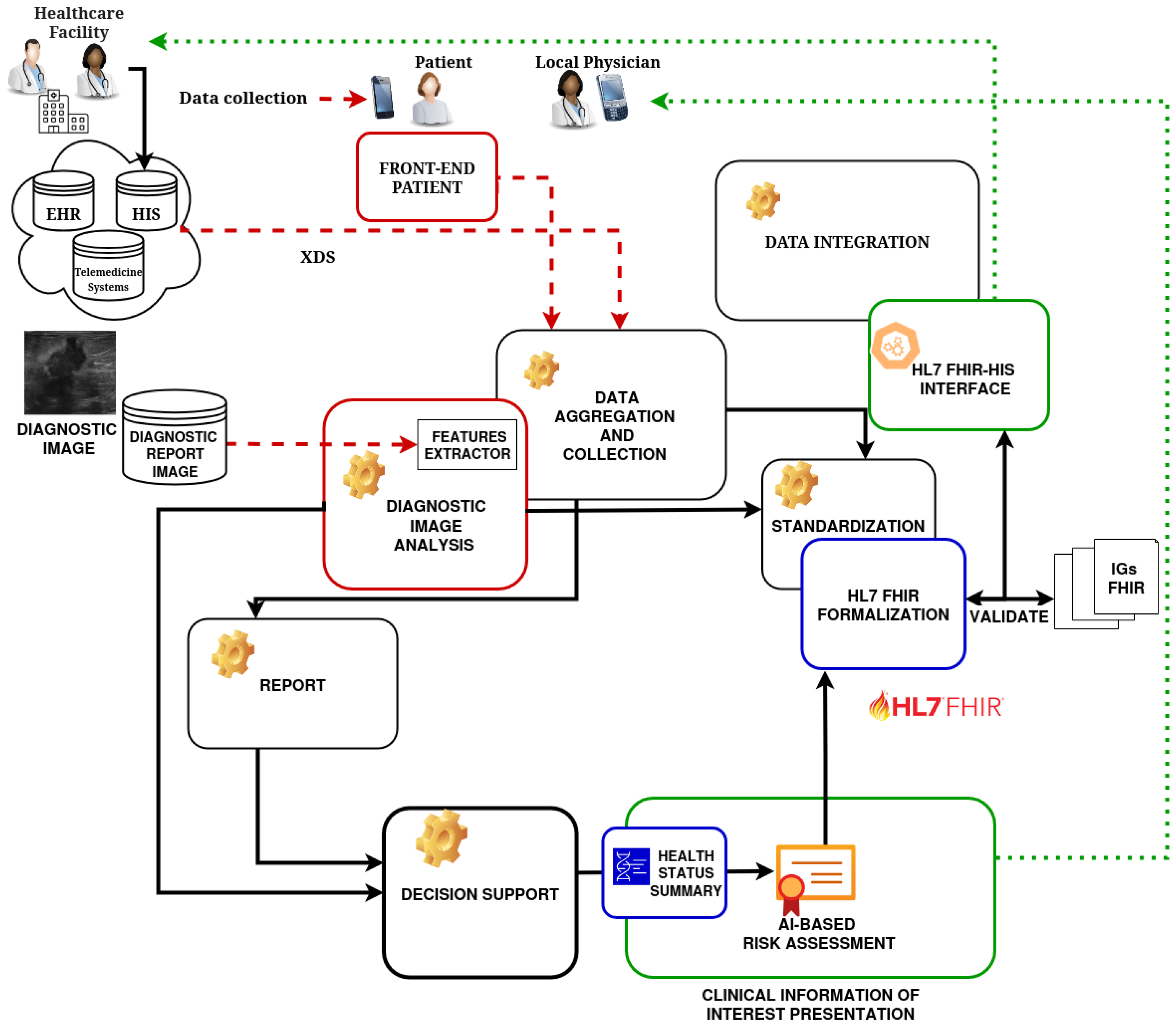

- Data Interoperability: Existing clinical systems do ot provide an integrated and patient-centered ecosystem that unifies anamnesis, structured clinical documents, diagnostic imaging, and AI-based decision support within a single workflow. The proposed architecture addresses this gap by integrating patient historical records, diagnostic imaging data, and risk assessment information originating from heterogeneous data sources. Interoperability is ensured through compliance with the HL7 FHIR standard, facilitating standardized data exchange and semantic consistency across HISs.

- Standard-driven AI integration: AI modules are integrated in compliance with recognized interoperability and transparency standards, ensuring that all AI-based results remain traceable, interpretable, and consistent with the overall system workflow.

- Bidirectional data flow: The clinical information collected from patients, encompassing medical history and diagnostic results, is semantically structured and encoded as HL7 FHIR resources. This approach enables standardized representation and supports bidirectional interoperability with heterogeneous external HIS, allowing both the retrieval of existing clinical data and the transmission of processed or newly generated information.

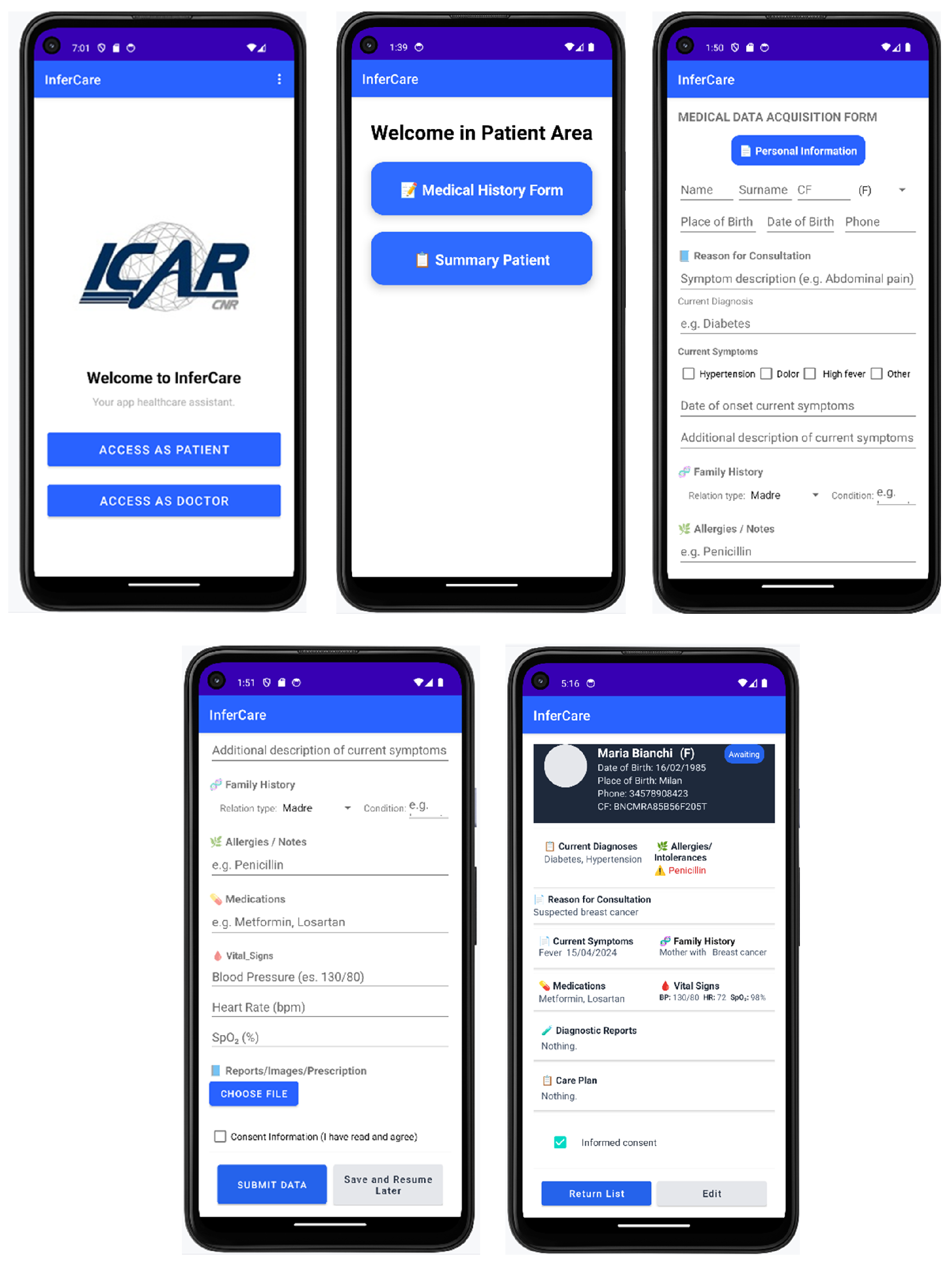

- User interaction: The InferCare application offers an intuitive interface that enables seamless interaction between patients and clinicians, effectively bridging mobile health (mHealth) solutions and institutional HIS.

- Clinical focus and validation: The interactions among the modules within the proposed architecture are demonstrated through a breast cancer case study based on US images analysis. This evaluation highlights the feasibility of integrating modules implementing ML algorithms with interoperability modules, thereby validating the system’s capacity to support clinically relevant diagnostic workflows.

2. Related Works

3. Integrated Patient Decision Support System—Architecture and Methodology

- Data Aggregation and Collection: Aggregating information from different sources, such as (i) information collected from interviews or through forms filled in by patients (medical and family history); (ii) data derived from diagnostic image analysis systems and reports; (iii) structured data obtained from HIS.

- Data Standardization: Formalizing all data (source, integrated, and processed) using the international HL7 FHIR standard to realize an interoperable solution.

- Intuitive and fast visualization of interest information: Providing integrated information of interest for healthcare professionals through an easy-to-navigate and understand user interface. Only information deemed useful is displayed for the specific diagnostic case.

- Decision Support: Generating a concise summary of the patient’s health status based on the integrated data and the use of AI algorithms to propose an AI-based risk assessment.

- Data Integration and Communication: Following data processing and integration, the architecture builds and manages HL7 FHIR-compliant resources that represent patient information, diagnostic results, and derived information. These resources are then sent to external systems such as HIS and EHR, contributing to the enrichment of patient clinical information and the overall increase in clinical knowledge related to patient health status.

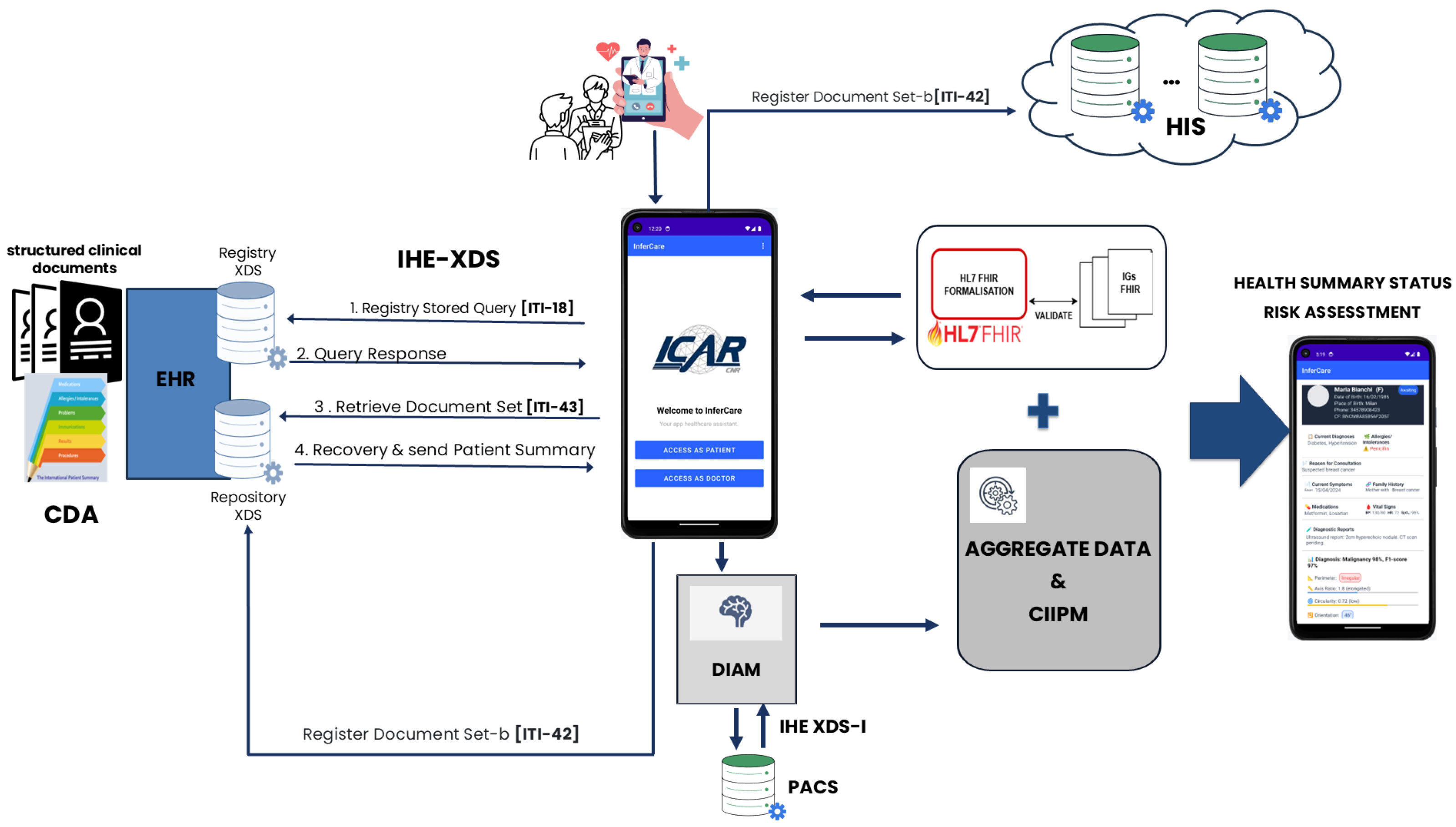

3.1. Architecture

- Front-end PatientIt allows the patient to independently collect a range of anamnestic information (possibly specific to the clinical condition). The module allows for the management of data obtained by a form presented to the patient for the collection of medical history and other relevant information (allergies, medication, family history, symptoms, etc.). This module also allows the patient to retrieve any information present in the system through interaction with the HL7 FHIR-HIS interface module.

- Diagnostic Image Analysis Module (DIAM)It performs processing and analysis of diagnostic images (e.g., detection, segmentation, classification, feature extraction) using ML algorithms or specific analysis tools. The aim of this module is to return an AI-based risk assessment.

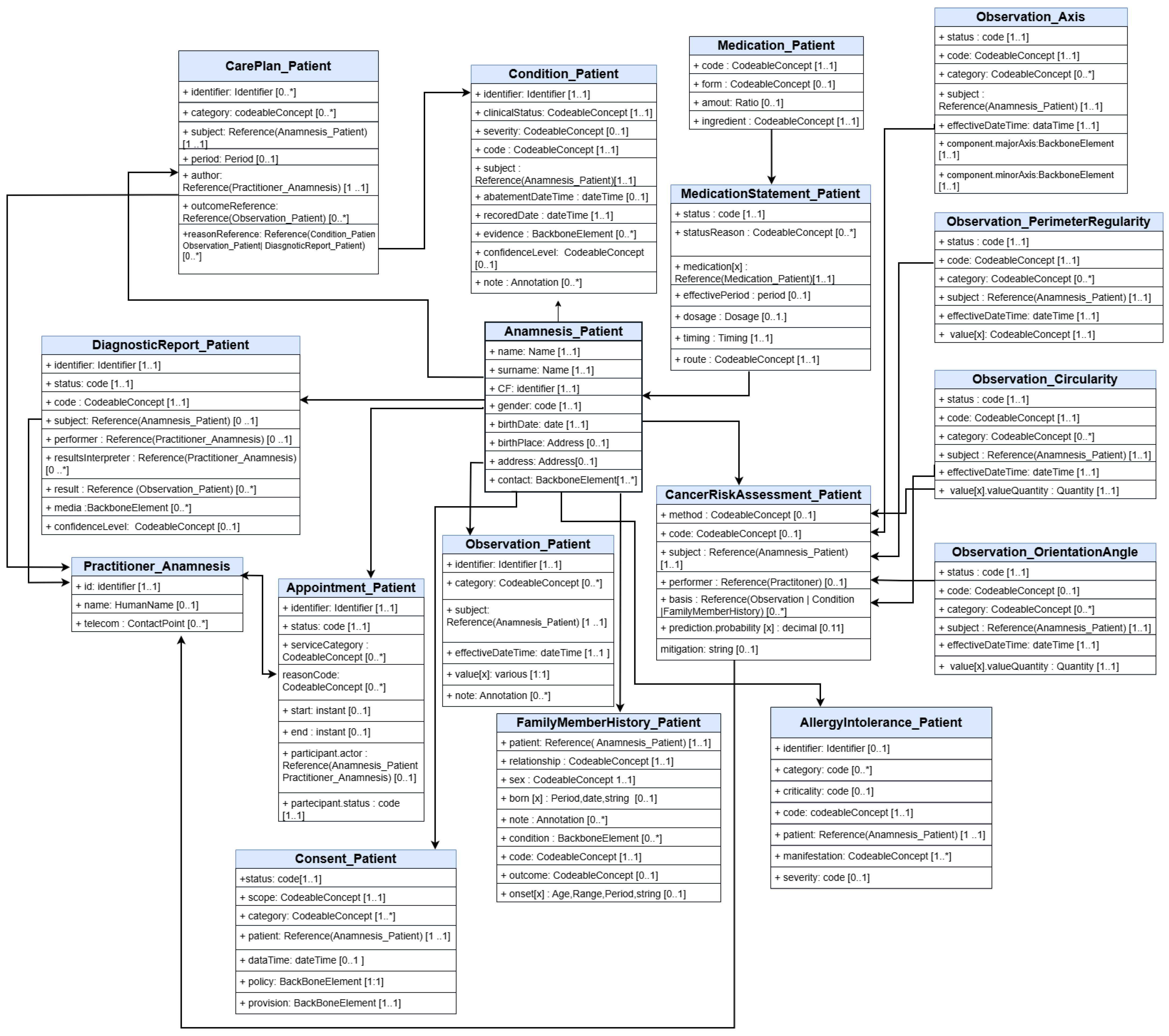

- HL7 FHIR Formalization Module (HFFM)This module allows for formalizing, through international standard HL7 FHIR profiles, the data provided by the patient during the anamnesis phase (coming from the patient’s anamnesis form), and the results of image analysis (from the DIAM). This module uses the FHIR profiles and resources (e.g., Patient, Observation, Diagnostic Report, Allergy Intolerance, Medication Statement), which are appropriately defined to ensure compliance with FHIR standards. It manages the creation of FHIR resources and carries out validation for the aim of proposed architecture.

- Clinical Information of Interest Presentation Module (CIIPM)This module allows identifying and collecting all and only the clinical information of interest for a specific diagnosis. It thus enables the presentation of an integrated and intuitive view of the information: personal data, structured medical history, and image analysis results.

- Health Status Summary ModuleIt applies logical rules and algorithms to extract and analyze integrated data (history, image results, other available data), and generates a concise summary of the patient’s health status, highlighting key information, potential risks (AI-based risk assessment), and recommendations.

- HL7 FHIR-HIS InterfaceIt enables the CIIPM to communicate with the existing platform (EHR) using the HL7 FHIR standard and supports FHIR operations such as Create, Read, Update of Patient resources, Observation, Diagnostic Report, and other relevant ones.

Data Model

3.2. Architecture Modules Details

3.2.1. Front-End Patient

3.2.2. Diagnostic Image Analysis Module (DIAM)

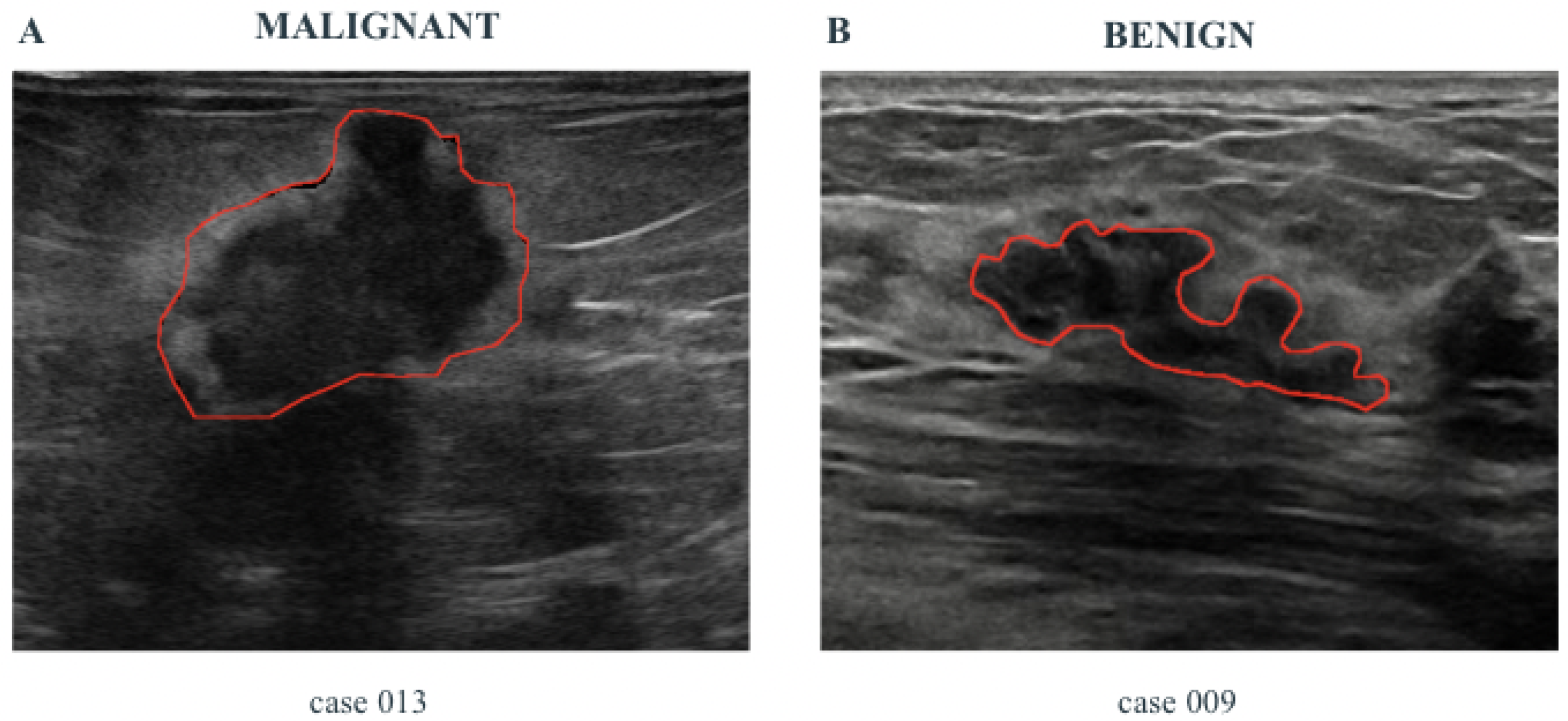

- Some specific features related to the pathology, namely Pathological Features (PFs), are automatically extracted from the images by using properly designed Computer Vision algorithms. These features are shown to the healthcare professionals and are useful to support the diagnosis.

- A risk assessment, computed by using suitably designed ML algorithms. For the computation of AI-based risk assessment, the ML methods use a set of features automatically extracted from US images, larger than PF, and called Hand-crafted Features (HFs).

3.2.3. HL7 FHIR Formalization Module (HFFM)

- Anamnestic data: information provided directly by the patient through the Front-end Patient module. This includes, for example, self-reported symptom medical conditions, self-reported symptoms, ongoing treatments, and relevant lifestyle factors.

- Clinical data derived from structured documents: information provided by external systems such as HIS/EHR.

- Clinical information derived from diagnostic images: includes results obtained through the automated analysis of diagnostic images (e.g., US images) by the DIAM. This information is then translated into formalized clinical observations according to the HL7 FHIR standard.

3.2.4. Clinical Information of Interest Presentation Module (CIIPM)

3.2.5. Health Status Summary Module

3.2.6. HL7 FHIR—HIS Interface

4. Case Study: Breast Cancer

4.1. Implementation of DIAM in the Breast Cancer Case

- Dataset description

- AI-based Risk assessment calculation

- Results

4.2. Implementation of HFFM in the Breast Cancer Case

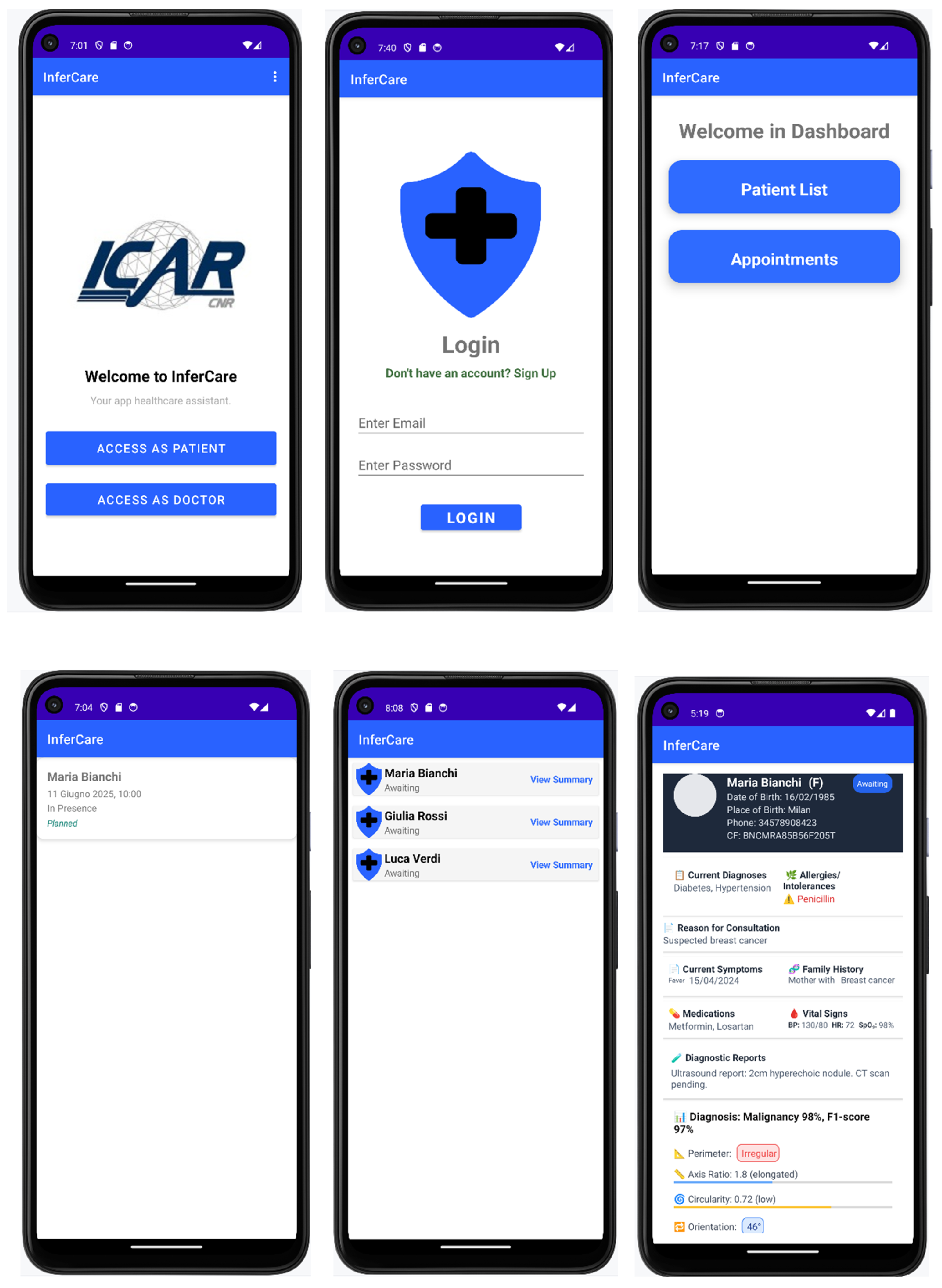

5. InferCare Android Application

5.1. IPDSS Functional Requirements

5.2. InferCare

5.3. User Actions and Interactions

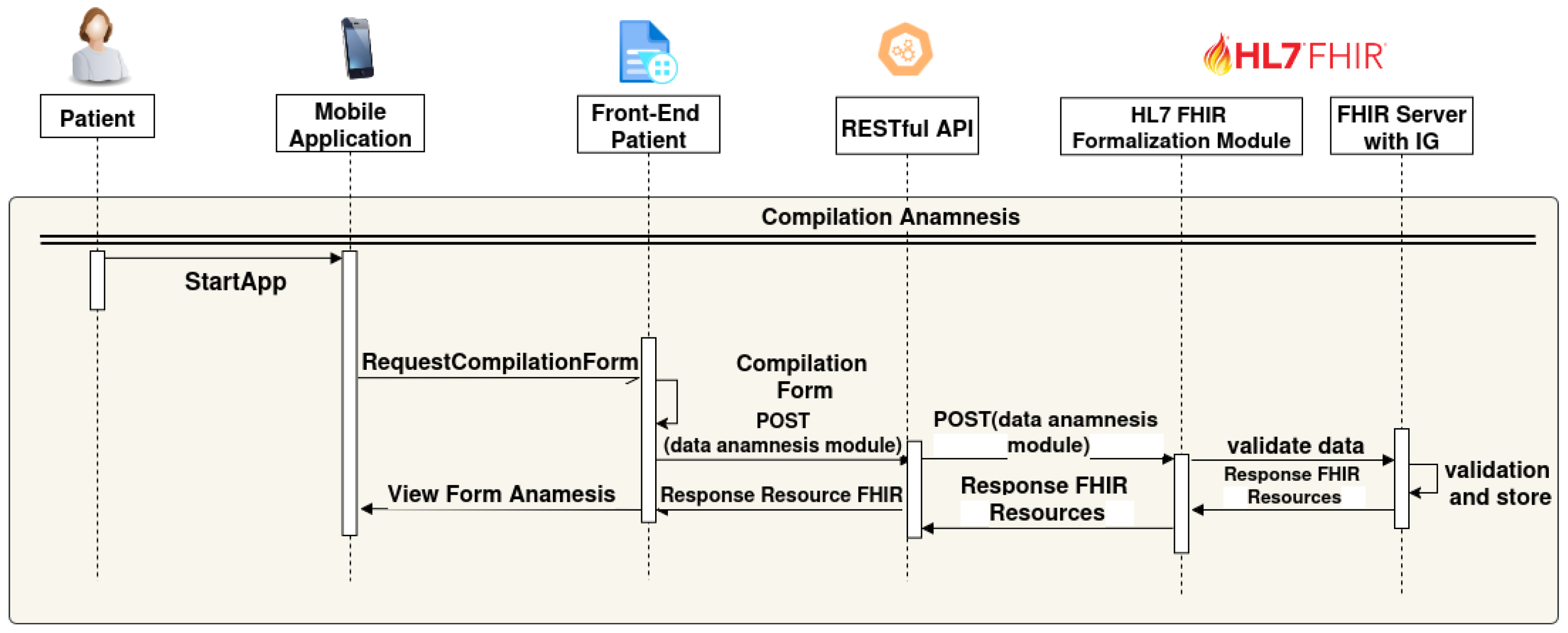

- The patient starts the mobile application (StartApp);

- A request is sent to the Front-end Patient to access the data entry form (RequestCompilationForm);

- The patient completes a digital form through the Front-end Patient interface;

- The Front-end Patient form sends the data to the Backend via a REST API (POST(data anamnesis module));

- The “RESTful API” forwards the “POST (data anamnesis module)” to the “HL7 FHIR Formalization Module”;

- The HL7 FHIR formalization module transforms the received data into FHIR resources and sends them to the “FHIR Server with IG” for data validation (“validate data”);

- FHIR Server with IG validates and stores the FHIR Resources, then data send a “Response FHIR Resources” back to the HL7 FHIR Formalization module;

- Finally, the “Front-End Patient” receives a “Response Resource FHIR” back to the mobile application as View Form anamnsesis.

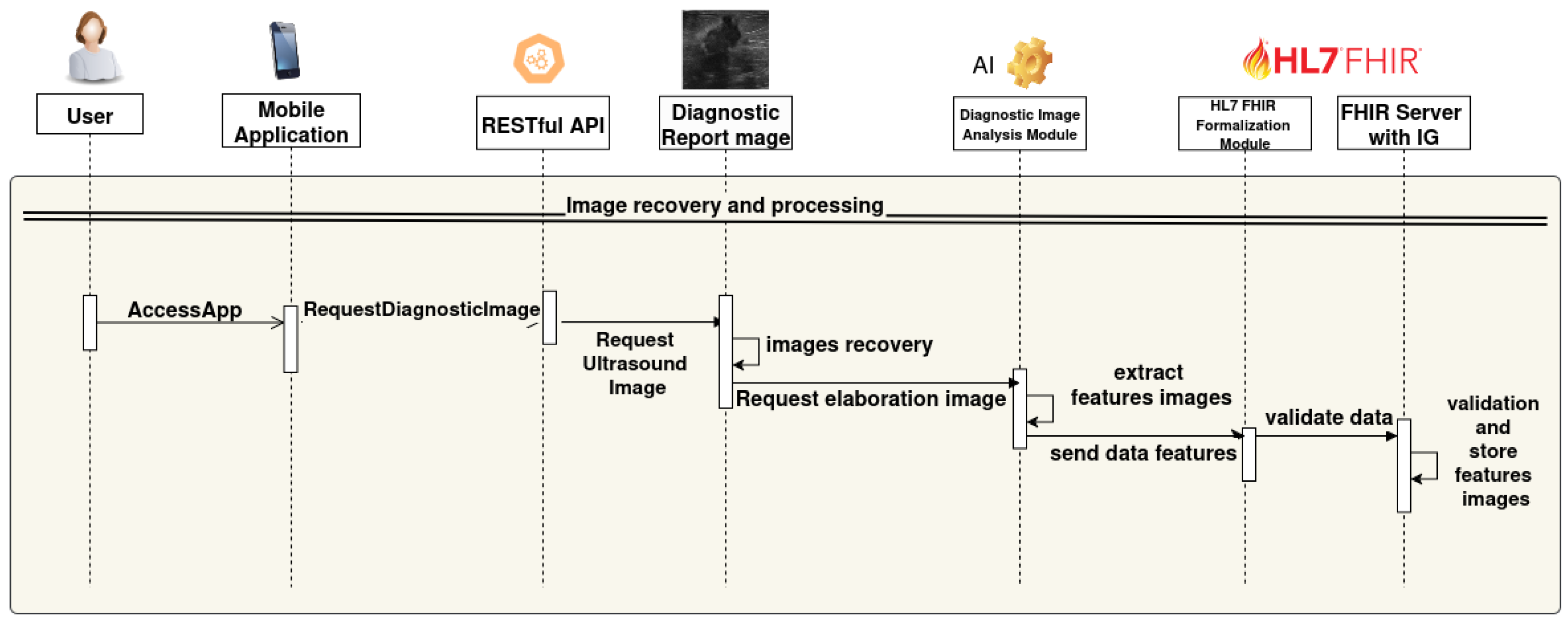

- The user accesses the mobile application (AccessApp).

- The application sends an image analysis request to the backend via RESTful API (RequestElaborationImage).

- The RESTful API performs a POST request to the module that queries the US image database.

- The database receives the request (RequestDiagnosticImage), retrieves the required US images (Images recovery), and returns them.

- The US images are sent to the AI-based image analysis module.

- The AI module extracts the clinical features from the ultrasound images (extract features images).

- The extracted data are sent to the HL7 FHIR formalization module (send data features).

- The HL7 FHIR module validates and transforms the data into FHIR format (validate data).

- Finally, the FHIR Server with IG stores the validated features (validation and store features images resource).

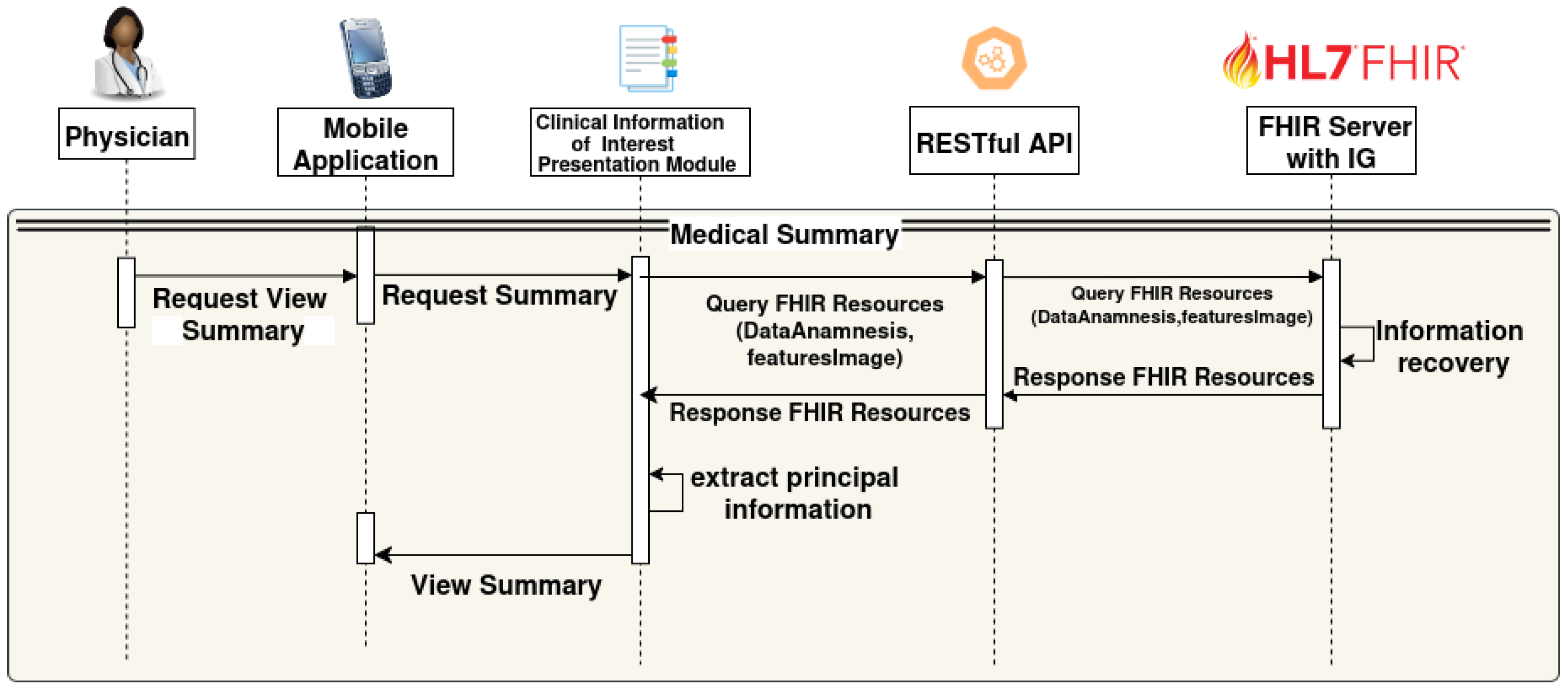

- The physician interacts with the mobile app to request the summary view (RequestViewSummary).

- The app forwards the request to the Clinical Information of Interest presentation module (RequestSummary).

- This module queries the FHIR Server through the RESTful API with a query containing the relevant data (Query FHIR Resources (DataAnamnesis, featuresImage)).

- The FHIR Server with IG retrieves the requested clinical information and returns the FHIR Resources.

- The Clinical Information of Interest presentation module extracts the main data from the received resources, creates a summary with a Health Status Summary and AI-based risk assessment, and highlights the principal information;

- The summary view is presented to the physician through the mobile interface (View Summary).

5.4. Data Flow Within the Architecture Enabled by the Developed InferCare

- Patient data collection: the process begins with the patient completing a digital medical history form through the InferCare mobile application. The guided interface enables the structured collection of personal and clinical information, including demographic data, symptoms and reasons for consultation, family and medical history, allergies, medications in use, informed consent, and the upload of relevant clinical documents.

- Retrieval of Clinical Documents (EHR–IHE-XDS): the InferCare application interfaces with the EHR through the IHE Cross-Enterprise Document Sharing (XDS) standard. Using the Registry Stored Query [ITI-18] IHE transaction, the app queries the XDS Registry to identify structured clinical documents associated with the patient. The registry provides the Query Response, allowing the system to retrieve the corresponding document set (Retrieve Document Set [ITI-43]) from the XDS Repository.

- Integration with Diagnostic Imaging Systems (IHE XDS-I/PACS): when a new diagnostic request is issued, the EHR communicates with the architecture to identify relevant imaging studies stored in multiple PACS systems. The application queries each PACS using the DICOM standard to identify and retrieve imaging objects associated with the patient. These objects are then referenced and managed using the IHE XDS-I profile, which ensures image accessibility within the EHR ecosystem. Once retrieved, the imaging data are processed by the DIAM. This module performs automated preprocessing, lesion detection, and feature extraction.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ABUS | Automated Breast Ultrasound System |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Diagnosis |

| DSS | Clinical Decision Support System |

| CIIPM | Clinical Information of Interest Presentation Module |

| CIC | Clinical Information Council |

| CIMI | Clinical Information Modeling Initiative |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DIAM | Diagnostic Image Analysis Module |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EMR | Electronic Medical Record |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| FR | Functional Requirement |

| HFFM | HL7 FHIR Formalization Module |

| HF | Hand-crafted Features |

| HIS | Health Information System |

| HL7 | Health Level Seven International |

| ICE | Integrated Clinical Environment |

| ICHOM | International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement |

| IG | Implementation Guide |

| IHE | Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise |

| IPDSS | Integrated Patient Decision Support System |

| IPS | International Patient Summary |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| mCODE | Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MDIRA | Medical Device Interoperability Reference Architecture |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| OSIRIS | Open Standards for Interoperable and Reusable Information in Oncology |

| PF | Pathological Features |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RFE | Recursive Feature Elimination |

| REST | Representational State Transfer |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| US | Ultrasound |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

| XDS | Cross-Enterprise Document Sharing |

References

- Adler-Milstein, J.; Holmgren, A.J.; Kralovec, P. Electronic Health Record Adoption and Interoperability among U.S. Hospitals. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Lentini, S.; Grosso, E.; Masala, G.L. A Comparison of Data Fragmentation Techniques in Cloud Servers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Internet, Data & Web Technologies; Barolli, L., Xhafa, F., Javaid, N., Spaho, E., Kolici, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 560–571. [Google Scholar]

- Mercy, W.; Annabel, L.S.P. Secure Electronic Health Record Storage in the Cloud Based on Multiple Fragmentation and Reconstruction Using Blockchain with Cryptographic Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICUIS), Gobichettipalayam, India, 12–13 December 2024; pp. 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejith, R.; Senthil, S. Smart Contract Authentication assisted GraphMap-Based HL7 FHIR architecture for interoperable e-healthcare system. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramgopal, S.; Sanchez-Pinto, L.N.; Horvat, C.M.; Carroll, M.S.; Luo, Y.; Florin, T.A. Artificial intelligence-based clinical decision support in pediatrics. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 93, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda, S.N.; Kennedy, N.; Conway, D.; Cheng, A.C.; Nguyen, V.; Zayas-Cabán, T.; Harris, P.A. HL7 FHIR-based tools and initiatives to support clinical research: A scoping review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29, 1642–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, P.; Radloff, C.; Del Fiol, G.; Staes, C.; Kawamoto, K. New standards for clinical decision support: A survey of the state of implementation. Yearb. Med Inform. 2021, 30, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, R.; Tang, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, A.; Qiao, Y. A multicenter hospital-based diagnosis study of automated breast ultrasound system in detecting breast cancer among Chinese women. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2018, 30, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.K.; Lee, Y.W.; Ke, H.H.; Lee, S.H.; Huang, C.S.; Chang, R.F. Computer-aided diagnosis of breast ultrasound images using ensemble learning from convolutional neural networks. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 190, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, S.M.; Mohamed, A.E.N.A.; Hefnawy, A.A.; Zidan, H.E.; GadAllah, M.T.; El-Banby, G.M. Classification of breast ultrasound images based on convolutional neural networks-a comparative study. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Telecommunications Conference (ITC-Egypt), Alexandria, Egypt, 13–15 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seiler, S.J.; Neuschler, E.I.; Butler, R.S.; Lavin, P.T.; Dogan, B.E. Optoacoustic imaging with decision support for differentiation of benign and malignant breast masses: A 15-reader retrospective study. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2023, 220, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, M.G.; Kim, Y.; Jung, G.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Bae, H.M. Enhancing Breast Cancer Detection through Advanced AI-Driven Ultrasound Technology: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Vis-BUS. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Shen, D. Interactive computer-aided diagnosis on medical image using large language models. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Montaha, S.; Raiaan, M.A.K.; Rafid, A.R.H.; Mukta, S.H.; Jonkman, M. An automated decision support system to analyze malignancy patterns of breast masses employing medically relevant features of ultrasound images. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.; Albukhari, A.; Alyami, J.; Mansour, R.F. Ensemble deep-learning-enabled clinical decision support system for breast cancer diagnosis and classification on ultrasound images. Biology 2022, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, M.I.; Abdel-Rahman, S.; Bdair, T.M.; Al-Najar, M.S.; Al-Hawari, F.H.; Alazrai, R. Breast tumor classification in ultrasound images using combined deep and handcrafted features. Sensors 2020, 20, 6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Ramos, C.; Garcia-Avila, O.; Almaraz-Damian, J.A.; Ponomaryov, V.; Reyes-Reyes, R.; Sadovnychiy, S. Benign and malignant breast tumor classification in ultrasound and mammography images via fusion of deep learning and handcraft features. Entropy 2023, 25, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Bianconi, F.; Du, H.; Jassim, S. Hand-crafted Vs. deep CNN features to distinguish benign from malignant lesions in breast ultrasound images. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD), Barcelona, Spain, 1–3 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Abhisheka, B.; Biswas, S.K.; Purkayastha, B.; Das, S. Integrating deep and handcrafted features for enhanced decision-making assistance in breast cancer diagnosis on ultrasound images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 43263–43285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, F.; Rahbar, K. Improving breast cancer classification in fine-grain ultrasound images through feature discrimination and a transfer learning approach. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 106, 107690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Appiah, K.; Amankwaa-Frempong, E.; Kwok, S.C. Classification of 2d ultrasound breast cancer images with deep learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 5167–5173. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, J.C.; Kreda, D.A.; Mandl, K.D.; Kohane, I.S.; Ramoni, R.B. SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, B.R.; Archer, N.; Sartipi, K.; Yuan, Y. Drishti: A Sense-Plan-Act Extension to Open mHealth Framework Using FHIR. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 1st International Workshop on Software Engineering for Healthcare (SEH), Montreal, QC, Canada, 27 May 2019; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, E.B.; Cooper, T.; Silva, R. MDIRA: IEEE, IHE, and FHIR Clinical Device and Information Technology Interoperability Standards, bridging Home to Hospital to “Hospital-in-Home”. In Proceedings of the SoutheastCon 2021, Virtual, 10–14 March 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J. Design of an ECG Stream Analysis Framework Based on FHIR Data Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 Fifteenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Budapest, Hungary, 2–5 July 2024; pp. 567–569. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman, T.J.; Terry, M.; Miller, R.S. Improving Cancer Data Interoperability: The Promise of the Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE) Initiative. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, 4, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chiang, Y. Applying the Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE) to the Asia-Pacific Region. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, J.; Laizet, Y.; Le Texier, V.; Chanas, L.; Rance, B.; Koeppel, F.; Lion, F.; Gourgou, S.; Martin, A.L.; Tejeda, M.; et al. OSIRIS: A Minimum Data Set for Data Sharing and Interoperability in Oncology. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, V.J.; Wang, W.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y. Enabling AI-Augmented Clinical Workflows by Accessing Patient Data in Real-Time with FHIR. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), Houston, TX, USA, 26–29 June 2023; pp. 531–533. [Google Scholar]

- Chishtie, J.; Sapiro, N.; Wiebe, N.; Rabatach, L.; Lorenzetti, D.; Leung, A.A.; Rabi, D.; Quan, H.; Eastwood, C.A. Use of Epic electronic health record system for health care research: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e51003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretokin, V.; Basdekis, I.; Kouris, I.; Maggesi, J.; Sicuranza, M.; Su, Q.; Acebes, A.; Bucur, A.; Mukkala, V.J.R.; Pozdniakov, K.; et al. Overview of the SMART-BEAR Technical Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health, Online, 23–25 April 2022; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2022; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, T.; Sicuranza, M. Sistema FHIR-Based per la Raccolta Strutturata dell’Anamnesi in Remoto: Approccio, Standard e Implementazione; Rapporto Tecnico RT-ICAR-NA-2025-05; CNR-ICAR: Napoli, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- HL7 International. International Patient Summary (IPS) Implementation Guide. Available online: https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-ips/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Teresa Conte and Mario Sicuranza. Remote Anamnesis Implementation Guide for Technical Report. Available online: https://anamnesi.na.icar.cnr.it/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Teresa Conte and Mario Sicuranza. Remote Anamnesis Implementation Guide. Available online: http://remote-anamnesis.na.icar.cnr.it (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Guo, R.; Lu, G.; Qin, B.; Fei, B. Ultrasound imaging technologies for breast cancer detection and management: A review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2018, 44, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Magee, J.F. Decision Trees for Decision Making; Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Internal Representations by Error Propagation; Technical Report; Institute for Cognitive Science, California University San Diego: La Jolla, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Iba, W.; Thompson, K. An analysis of Bayesian classifiers. In Proceedings of the AAAI, San Jose, CA, USA, 12–16 July 1992; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 1992; Volume 90, pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 August 1995; Volume 1, pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard HL7 FHIR. HL7 Documentation. Available online: https://www.hl7.org/fhir/documentation.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- HL7. SUSHI – SUSHI Unshortens Short Hand Inputs. Available online: https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-shorthand/overview.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- HL7. IG Publisher. Available online: https://confluence.hl7.org/plugins/servlet/mobile?contentId=35718627#content/view/35718627 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Concept to Be Mapped | Source Data | FHIR Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Allergy or Intolerance | IPS CDA 2.0 | AllergyIntolerance_Patient |

| Appointment | Physician interview and source app | Appointment_Patient |

| Risk Assessment | DIAM | CancerRiskAssessment_Patient |

| Care Plan | IPS CDA 2.0 | CarePlan_Patient |

| Condition | IPS CDA 2.0 | Condition_Patient |

| Consent of Patient | App and EHR source | Consent_Patient |

| Diagnostic Report | IPS CDA 2.0 | DiagnosticReport_Patient |

| Family Member History | IPS CDA 2.0 and physician interview | FamilyMemberHistory_Patient |

| Medication | IPS CDA 2.0 | Medication_Patient/ MedicationStatement_Patient |

| Feature Major Axis, Minor Axis | DIAM | Observation_Axis |

| Observation (symptoms, etc.) | IPS CDA 2.0 | Observation_Patient |

| Feature Orientation | DIAM | Observation_Orientation |

| Feature Circularity | DIAM | Observation_Circularity |

| Feature Perimeter Regularity | DIAM | Observation_PerimeterRegularity |

| Patient | Patient app | Anamnesis_Patient |

| Physician | App or interview | Practitioner_Anamnesis |

| Procedure | IPS CDA 2.0 | Procedure_Patient |

| CDA | FHIR |

|---|---|

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/id | AllergyIntolerance/identifier |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/text | AllergyIntolerance/text |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/statusCode | AllergyIntolerance/status |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/effectiveTime | AllergyIntolerance/recordedDate |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship /observation/code | AllergyIntolerance/type |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship /observation/effectiveTime | AllergyIntolerance/onset |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship/ observation/participant/participantRole/ playingEntity/code | AllergyIntolerance/substance |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component/ section/entry/act/entryRelationship/ observation/entryRelationship/ observation/effectiveTime | AllergyIntolerance/reaction/onset |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship/ observation/entryRelationship/observation/value | AllergyIntolerance/reaction/manifestation |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship/ observation/entryRelationship/observation/value | AllergyIntolerance/reaction/certainty |

| ClinicalDocument/structuredBody/component /section/entry/act/entryRelationship/ observation/entryRelationship/act/text | AllergyIntolerance/note |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Major Axis, Minor Axis | Provides intuitive size and shape information |

| Perimeter Regularity | Irregular contours may be indicative of malignancy |

| Orientation | An angle greater than 45° may suggest a malignant nature |

| Circularity | Lower circularity can reflect irregular lesion shapes |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Eccentricity | Indicates how elliptical the lesion is (0 = perfect circle, 1 = highly elongated ellipse) |

| Circularity | Measures how similar the lesion is to a circle (1 = perfect, <1 = more irregular) |

| Perimeter Regularity | Evaluates the complexity of the lesion boundary |

| Axis Ratio | Relationship between the axes of an ellipse or ellipsoid |

| Solidity | Ratio between the actual area and the convex area (1 = compact, <1 = irregular) |

| Extent | Ratio between the lesion area and its bounding box |

| Elongation | Indicates whether the lesion is stretched along a particular direction |

| Fractal Dimension | Quantifies the complexity of the lesion’s contour |

| Area | Number of pixels comprising the lesion |

| Perimeter | Length of the lesion’s contour |

| Convex Area | Area of the convex hull surrounding the lesion |

| Equivalent Diameter | Diameter of a circle having the same area as the lesion |

| Kurtosis | Measures the “peakedness” of the intensity distribution |

| Skewness | Measures the asymmetry of the intensity distribution |

| Entropy | Indicates the degree of randomness in the pixel intensity distribution |

| Contrast | Measures local intensity variation |

| Homogeneity | Quantifies how similar neighboring pixels are |

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | ||||

| MLP | ||||

| NB | ||||

| RF |

| Profile | Description |

|---|---|

| AllergyIntolerance_Patient | Used to represent the patient’s known allergies and intolerances |

| Anamnesis_Patient | Used to represent the personal identity and demographic information of the patient subject to the anamnesis |

| Appointment_Patient | Used to describe information about scheduled clinical appointments |

| CancerRiskAssessment_Patient | Used to represent the patient’s risk of developing cancer based on anamnesis and extracted clinical features |

| CarePlan_Patient | Used to represent a patient care or treatment plan |

| Condition_Patient | Used to represent a particular clinical condition of the patient |

| Consent_Patient | Used to represent the patient’s informed consent regarding the use and sharing of their clinical data |

| DiagnosticReport_Patient | Used to document diagnostic reports associated with the patient, such as US images |

| FamilyMemberHistory_Patient | Used to document the patient’s family medical history, with special reference to inherited diseases in family members |

| Medication_Patient | Used to describe the characteristics of drugs such as active ingredient, pharmaceutical form, and dosage |

| MedicationStatement_Patient | Used to represent the set of medications taken by the patient |

| Observation_Axis | Used to represent the orientation axis of a clinical image or structure, extracted from US or imaging data. |

| Observation_PerimeterRegularity | Used to represent the regularity of the perimeter of a lesion or structure observed in diagnostic imaging |

| Observation_Orientation | Used to represent the spatial orientation of a lesion as detected in clinical imaging. |

| Observation_Circularity | Used to represent the circularity of a lesion or structure, derived from diagnostic image analysis |

| Observation_Patient | Used to record observations of the patient’s health status such as vital parameters, symptoms, etc. |

| Practitioner_Anamnesis | Used to represent the health professional involved in patient care, e.g., the physician in charge of the examination. |

| Procedure_Patient | Used to represent medical procedures undergone by the patient, such as surgeries, biopsies, or diagnostic interventions |

| Requirement ID | Description |

|---|---|

| FR01 | IPDSS should enable patients to complete a structured form capturing personal data, teleconsultation history, family medical history, allergies, current medications, lifestyle habits, ongoing symptoms, and other clinically relevant information necessary for initial assessment. |

| FR02 | The form should support multiple input types, including free text fields, multiple-choice options, checkboxes, and date pickers, to ensure flexibility and completeness of data collection. |

| FR03 | IPDSS should implement client-side validation mechanisms to ensure data consistency, accuracy, and completeness before submission. |

| FR04 | IPDS should allow patients to save their progress during form completion and resume the process at a later time without data loss. |

| FR05 | IPDSS should ensure the confidentiality and integrity of the submitted information during data transmission through secure communication protocols (e.g., HTTPS, encryption). |

| FR06 | A secure user authentication mechanism should be provided (where applicable) to control access to the form, particularly when enabling partial form saving or editing features. |

| FR07 | IPDSS should be responsive and accessible across various devices, including tablets and smartphones, ensuring usability and inclusivity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brancati, N.; Conte, T.; De Pietro, S.; Russo, M.; Sicuranza, M. Machine Learning-Enhanced Architecture Model for Integrated and FHIR-Based Health Data. Information 2025, 16, 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121054

Brancati N, Conte T, De Pietro S, Russo M, Sicuranza M. Machine Learning-Enhanced Architecture Model for Integrated and FHIR-Based Health Data. Information. 2025; 16(12):1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121054

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrancati, Nadia, Teresa Conte, Simona De Pietro, Martina Russo, and Mario Sicuranza. 2025. "Machine Learning-Enhanced Architecture Model for Integrated and FHIR-Based Health Data" Information 16, no. 12: 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121054

APA StyleBrancati, N., Conte, T., De Pietro, S., Russo, M., & Sicuranza, M. (2025). Machine Learning-Enhanced Architecture Model for Integrated and FHIR-Based Health Data. Information, 16(12), 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121054