Abstract

Analyzing 2,309,573 tweets by S&P 500 firms along with 2,498,767 public replies, we examine how firms’ ESG communication tactics on social media influence the micro-level accumulation of reputational capital. Leveraging the prior communication literature, we categorize firms’ ESG messages based on three primary communication functions: Information, Community-Building, and Action. Information-based tactics unidirectionally disseminate knowledge; community-building tactics foster engagement and relationship-building; and action-based tactics seek to mobilize stakeholders to take direct action. Our results indicate that information-focused ESG messages relate to reputational awareness, whereas community-building tactics are associated with reputational favorability. Additional analyses reveal different audience response patterns between ESG-specific and general corporate messaging as well as between B2C and B2B firms. This study provides evidence of new, non-reporting-based ESG communication tactics and illustrates how firms accumulate reputational capital on a micro, message-by-message, day-to-day level. Our findings offer insights into the strategic use of ESG communication to enhance corporate reputation.

1. Introduction

Reputation is increasingly seen as a strategic, value-enhancing asset [1,2]. While such assets have traditionally been difficult to measure, the dynamic, publicly visible nature of audience reactions to companies’ social media messages offers managers a unique opportunity to measure and track reputational capital. Social media also offers the ability to engage in a variety of communicative styles that are better than formal annual reporting at building reputation [3,4,5,6]. In fact, in an information environment increasingly driven by social media, the role of one-way, once-a-year firm reporting has become less relevant. In this new context, firms do not only disclose ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance, they also communicate [7], going beyond uni-directional reporting of ESG activities to engage stakeholders in two-way dialogic and mobilizational communication [8,9,10,11].

Yet because CSR and ESG research has been dominated by the study of formal reporting [12,13], we don’t have much evidence of how other forms of communication—either alone or in conjunction with disclosure—may be effective at improving reputational outcomes [14]. In response, our paper offers a micro-level study of the relationship between ESG communication and reputation that addresses three research questions. First, which communication tactics are used in firms’ ESG efforts on social media (RQ1)? Second, how do the different communication tactics influence the accumulation of reputational capital (RQ2)? Third, do ESG disclosures have a different reputational effect when paired with community-building and action-oriented tactics (RQ3)?

To address RQ1, the study employs a structured combination of deductive and inductive approaches, leveraging the Information–Community–Action (ICA) communication function framework from the communication literature [9] as a theoretical foundation. Analyzing ESG-focused tweets sent by S&P 500 firms from 2020–2022, we deductively categorize ESG messages into these three primary communication functions and then inductively identify eight distinct communication tactics within these categories—including four information-focused tactics and four community-building and action-oriented tactics. Using supervised machine learning techniques [15,16,17], we then classify all 2,309,573 tweets sent by S&P 500 firms from 2020–2022, including their 10,851 ESG-focused tweets, according to these eight communication tactics. RQ2 is then addressed through a series of regressions examining how these communication tactics influence the accumulation of reputational capital, operationalized along two core dimensions: awareness, as reflected in the public’s retweeting of firms’ messages; and favorability, as reflected in the sentiment in public replies to those messages (see [18,19]). RQ3 is addressed by regressions that examine how community-building and action-oriented tactics moderate the reputational effects of the ESG disclosure tactic. To identify how audience and firm context influences communication effectiveness, additional analyses extend our tests to examine both the full dataset of 2.3 million general corporate tweets and separate subsamples of B2C and B2B firms.

This study makes several contributions to the ESG and AIS literature. To start, in taking the accounting practice of ESG disclosure and expanding it to ESG communication, the study responds to calls “to move away from disclosure as a central object” of studies examining ESG and consider instead a broader range of communication approaches (see [5,10,12,20]). While a large proportion of firm messages are still classified as disclosure, we also find evidence of new, non-disclosure-focused information types—particularly “public education” messages—and a number of community-building and action-oriented communicative tactics.

Second, in examining the reputational tokens visible in public reactions to corporate ESG messages, the study helps address the identified need for greater understanding of stakeholder reactions to ESG disclosures [5,21,22] along with calls to look beyond “a narrow, shareholder-centric focus” and consider how ESG communication may “become a tool of accountability” to non-shareholder publics [23].

Third, in illustrating how ESG-based reputational capital is accumulated on a message-by-message, day-to-day level, the study responds to calls for greater understanding of the micro-foundations of ESG efforts [24,25]. Our additional analyses further suggest how audience characteristics and firm type strongly influence the relationship between ESG communication tactics and reputational capital. Given how ESG accounting and reporting practices do not operate in isolation but instead can recursively effect changes in accounting practices [26], the implications of more “communicative” and reputation-based ESG reporting models on accounting information systems are worth further investigation.

In the following section we lay out our theoretical perspectives on reputational capital and the use of ESG communication tactics to build that capital. Method and results follow, and the paper ends with a discussion of the study’s implications for ESG reporting and AIS research.

2. ESG Communication and Corporate Reputation

2.1. ESG and Reputational Capital

Reputation can be defined as a collective stakeholder assessment of a company’s performance relative to competitors [18,19,27]. This is closely in line with Fombrun and Van Riel’s [27] preferred definition: “A corporate reputation is a collective representation of a firm’s past actions and results that describes the firm’s ability to deliver valued outcomes to multiple stakeholders. It gauges a firm’s relative standing both internally with employees and externally with its stakeholders…” (p. 10). The authors also provide an exhaustive review of alternative definitions. Though the terms reputation and reputational capital are, in our view, interchangeable, our use of the term reputational capital emphasizes its role as a strategic, value-enhancing intangible asset [2]. Consistent with the accounting literature that conceptualizes corporate reputation as a non-monetized, non-financial construct [28,29], our approach focuses not on direct financial valuation but rather on empirical measurement, employing observable stakeholder responses as empirical proxies for this otherwise difficult-to-quantify construct [30]. The accounting and management literature has a long-established precedent for using non-monetary proxies to measure intangible constructs like reputation. For example, Raithel and Schwaiger [31] demonstrate that nonfinancial aspects such as product quality, workplace environment, and social responsibility contribute to measuring reputation. Similarly, survey-based rankings such as the Fortune Most Admired Companies index have been extensively used in reputation research [32]. Media sentiment [33,34] has also been used to proxy for corporate reputation.

Despite its importance, we do not have a solid understanding of how firms gain reputational capital through their ESG efforts [14,24]. First, there is little examination of the processes by which such capital is acquired; with legitimacy and reputation typically examined cross-sectionally at a single point in time, we have insights into the stock of perceptions but not the flow. Second, as noted by Moser and Martin [21] and Tsang et al. [22], there remains a dearth of understanding of “how investors and other stakeholders react” to ESG disclosures and performance. Third, as argued by Aguinis and Glavas ([24] p. 955 and [25]), given the “predominance of organizational- and institutional-level research,” there is a pressing need to examine the microfoundations of ESG. Lastly, particularly relevant in terms of the effects of audiences’ social media-based reactions and relationships, Gödker and Mertins [25] make the point that “identifying specifical behavioral drivers…and incorporating investors’ social interactions remain fundamental issues for future research” (p. 47). The present study addresses these issues by leveraging data on social media-based stakeholder reactions to examine the micro-level acquisition of ESG-based reputational capital.

Two Dimensions of Reputational Capital: Reputational Awareness and Favorability

The public visibility and interactivity present in social media [4] afford a unique opportunity for examining audience dynamics. Several recent studies have leveraged these qualities to examine a diverse array of audience reactions to firms’ ESG messages on social media, including content analyses of Facebook comments [35], audience interactivity and feedback on Twitter and Facebook [36], retweets on Twitter [20], and Facebook audiences’ use of likes, comments, shares, and “emotions” [5]. Building on this research, we first argue the public’s retweeting (sharing) of organizations’ ESG messages constitutes micro-level indicators of reputational awareness. Messages that are retweeted contain some “pass-along value” [37], and each retweet serves to expand the number of audience members that view the original message. While the organization’s number of followers on Twitter reflects the baseline number of users who potentially “see” a given firm message, each time a follower retweets that message, it is also rendered visible by the follower’s followers, which can substantially expand the message’s reach. In spreading the word, retweets thus directly impact the awareness dimension of reputational capital. Retweets have been used to capture a variety of different concepts in the literature, with some research focusing on how retweets reflect qualities of the message, such as its pass-along value [37] or validity [38], and others focusing on the outcomes of retweeting, particularly how retweets increase the dissemination [39] or diffusion of the message to a wider audience [20]. While both are valid uses of retweets, the latter is a more “direct” measure and is in line with our use of the retweet measure. At their core, retweets serve to boost dissemination by “expanding the number of people who receive a given message” [20], p. 363. and are thus tightly linked to the notion of awareness. Also known as familiarity, or prominence [18,19,40], awareness is one of the core dimensions of reputation and “reflects the degree to which opinions about an organization … are disseminated among its stakeholders” [19], p. 1038.

Awareness alone is not sufficient for capturing a firm’s ESG reputation. It is also necessary to find a way to capture the second key dimension of reputational capital, that related to the favorability [18], positive assessment [40], or perceived quality [19] of the firm’s ESG efforts. In our context, we can leverage machine learning techniques [15,16] to capture favorability through the presence of positive sentiment in audience replies to corporate ESG messages. The sentiment expressed in a public reply to a company tweet is a direct micro-level indication of the favorability with which the individual sees the firm’s message. The coding of the replies is important for another reason: like retweets, replies are linked to specific firm tweets, allowing the analyses to remain consistently focused on individual firm messages. Social media thus afford a unique opportunity for message-level analyses that examine the flow of both the awareness and favorability dimensions of CSR-driven reputational capital. This point is worth expanding on. It is only possible to develop and “see” reputational change by linking specific organizational actions to specific audience reactions. By focusing on the message level of analyses, we can generate insights into how specific individual messages engender specific reputational responses from members of the public.

In this context, we interpret retweets and replies as observable traces of audience attention and engagement—intermediate outcomes through which firms accumulate reputational capital. Retweets serve to expand message visibility and reflect reputational awareness, while positive replies indicate favorable stakeholder sentiment. This use of social media metrics as proxies for stakeholder perceptions is well established in accounting research (e.g., [38,39]).

2.2. ESG Communication on Social Media to Gain Reputational Capital

How can organizations build reputational capital? The answer: communication. There is substantial evidence that opinions and perceptions are changed not chiefly through the provision of information—such as disclosure [41]—but through the use of communicative tactics that actively shape meaning. These tactics work by educating, persuading, engaging, linking, and mobilizing stakeholders, fostering shared meanings and identities, and shifting the framing of key issues [42,43]. Social media excels in this space, with its facility at a broad range of communicative modes and styles that are better suited for persuasion and influencing public perceptions [4,16,44,45]. By providing a dynamic, “networked” environment [46], social media facilitates not only the dissemination of ESG-related information but also interactive engagement and stakeholder mobilization [7,47]. These communicative efforts also contribute to firms’ relative standing within their industries. By shaping how stakeholders perceive a firm’s values, commitments, and engagement strategies, ESG communication tactics may help distinguish the firm from its competitors, contributing to comparative reputational advantage.

Despite the growing use of social media for ESG communication, we lack a systematic understanding of non-reporting-based ESG messaging strategies and how these efforts influence public perceptions. The disclosure of ESG information is well documented in prior research [12], as is the importance of firm-stakeholder dialogue and engagement in shaping corporate reputation [10,48]. However, while existing studies have identified broad dialogic communication practices, we know relatively little about the specific communicative tactics firms use beyond simple disclosure and dialogue.

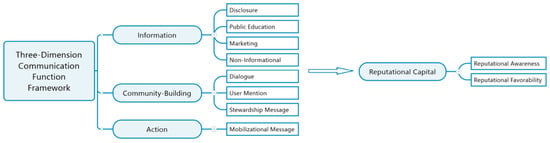

To address this gap, we adopt a communication-based perspective (for a review, see [49]) on ESG messaging, specifically drawing on the Information–Community–Action (ICA) framework [9]. This framework categorizes social media message into three primary communication functions: (1) Information-based tactics disseminate knowledge unidirectionally, often through disclosure or educational content, but do not directly engage stakeholders; (2) Community-building tactics foster engagement and relationship-building through two-way interaction, dialogue, and audience recognition; and (3) Action-based tactics seek to mobilize stakeholders to take direct action in support of ESG goals. By examining how communication tactics influence discrete audience responses—retweets and positive replies—we offer a methodological framework for tracking the incremental accumulation of reputational capital through social media engagement. This approach follows established accounting research on the measurement of intangible assets, where constructs like reputation are often captured using observable stakeholder responses (e.g., [2,38]). In this view, social media metrics act as empirical proxies for stakeholder perceptions that contribute to the development of reputational capital. Figure 1 presents our conceptual model, depicting how these three higher-level communicative functions and their eight underlying tactics (identified via inductive analysis) influence the two dimensions of reputational capital in our study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Figure shows relationship between communication tactics—including both the three higher-level dimensions and the 8 constituent tactics—and our two dimensions of reputational capital.

The first function, Information, extends beyond traditional disclosure to encompass a broader set of ESG-related messaging strategies. Prior research has primarily examined disclosure-focused ESG messaging, emphasizing the reporting of firms’ sustainability performance [12]. However, firms cannot always be “selling” their ESG performance on social media through one-way reporting; effective communication requires a mix of reporting- and non-reporting-based content [50]. While formal ESG disclosures remain central to corporate reporting, firms may also engage in public education efforts [51], knowledge-sharing [52], and promotional activities [53] to enhance their credibility and reach. Given the dearth of relevant research, we do not have a detailed understanding of what such nondisclosure information types might encompass. Prior research has looked at different ESG topics in social media messages [20,35], and also coded for the presence of disclosure [7,36,48,54], but not explicitly other information types.

The second function, Community-Building, reflects the role of stakeholder interaction, dialogue, and relationship-building in social media-based communication. In a fundamentally “networked” social media context [46] characterized by heightened firm–stakeholder communication [55], firms employ community-building tactics to strengthen relationships, foster engagement, and amplify ESG messaging [36,47]. Research suggests that such tactics, including dialogic communication and stakeholder recognition, play a crucial role in boosting awareness and spreading favorable opinions [44,56,57], the building blocks of corporate reputation (e.g., [19]). By cultivating relationships with key audiences and sustaining engagement, firms can build trust, enhance reputational capital, and expand the reach of their ESG narratives.

The third communication function, Action, goes beyond informing or engaging stakeholders to actively mobilizing them in ESG-related initiatives. Unlike Information-based tactics, which focus on disseminating knowledge, or Community-building tactics, which emphasize dialogue and relationship-building, Action-based communication seeks to motivate concrete behavioral responses from stakeholders. On social media, these tactics manifest as mobilizational messages that present a direct “call to action” to the organization’s stakeholders. In the ESG context, such mobilizational messages may encourage audiences to take such actions as participate in sustainability initiatives (e.g., corporate volunteering, climate change action), share ESG-related content to raise awareness, or take part in campaigns, petitions, or pledges. Firms that effectively leverage action-based tactics can potentially transform their sustainability messaging into tangible reputational benefits by fostering visible stakeholder participation. These tactics help organizations demonstrate commitment to ESG goals, enhance stakeholder trust, and reinforce corporate reputation through public engagement. While prior research has documented mobilization efforts in social movement and advocacy settings [43], how firms use action-based communication to build reputational capital in a corporate context remains underexplored.

In short, prior ESG research in accounting has largely concentrated on a single communication tactic: disclosure. While the AIS literature has explored non-disclosure-focused messaging to a limited extent [54] and prior ESG research in communication, public relations, and management provides evidence of dialogic tactics [7,10,36,48], a comprehensive understanding of the full spectrum of ESG communication tactics on social media is still lacking. In particular, we do not have a systematic understanding of how firms balance Information, Community, and Action-based communication on social media. While firms likely employ a diverse mix of strategies across these functions, the specific nature and prevalence of these tactics remain unclear. Our first research question, therefore, is the following:

RQ1:

Which communicative tactics are used by S&P 500 firms in their ESG messages on social media?

After identifying the tactics, the next task is to examine their relationship with the accumulation of reputational capital. There is strong initial evidence a broader set of tactics is better than disclosure at fostering positive public perceptions. Yet it remains an empirical question given the limited research on non-reporting forms of ESG communication [12]. Accordingly, our second research question is to examine how the broader range of communicative tactics identified through answering RQ1 influence the two dimensions of reputational capital:

RQ2a:

How do the communication tactics employed by firms in their ESG messages relate to the acquisition of reputational awareness?

RQ2b:

How do the communication tactics employed by firms in their ESG messages relate to the acquisition of reputational favorability?

On social media, community-building and action-oriented tactics can be employed separately from or in conjunction with different types of informational tactics. This raises the possibility that the impact of the chief traditional informational tactic—namely, disclosure—varies according to the other communication tactics that are employed in a disclosure-focused message. Our third research question thus asks whether ESG disclosures have a different effect when paired with community-building and action-oriented tactics:

RQ3:

How do the community-building and action tactics employed by firms in their ESG messages condition the reputational effects of ESG disclosure?

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data

Our dataset comprises Twitter activity from the main Twitter/X accounts of firms on the S&P 500 list from 2020–2022. All data were obtained from publicly available firm and user tweets via the Twitter API, in compliance with the platform’s terms of service. No private or deleted content was accessed, and analyses were conducted at an aggregate level without identifying individual users. While public tweets are generally considered open data, we acknowledge residual ethical concerns regarding privacy expectations, user consent, and representativeness [58]. We mitigate these concerns by focusing on organizational and aggregate patterns, consistent with best practices in computational social-science ethics [9,47]. We accessed the Twitter application programming interface (API) using Python version 3.9.7 code to collect all 2,309,573 original (non-retweet) messages sent by the 443 firms with accounts active across this period, as well as 2,498,767 public replies to their tweets. These general corporate accounts engage with a broad range of topics, including company performance, product updates, customer service, and social responsibility efforts. In additional analyses, this broader dataset allows us to examine how firms’ overall communication strategies relate to reputational capital, rather than isolating ESG-focused communication. For our main analyses focusing on ESG-specific messaging, we identified 10,851 tweets that contained one or more of 133 CSR, sustainability, or ESG-related hashtags from a list we developed. Two co-authors hand-coded all hashtags that were employed in 100 or more firm tweets and identified 133 relevant hashtags considered to focus on CSR, sustainability, and ESG topics, such as #ESG, which was used in 3105 tweets, and #Sustainability, which was used in 2686 tweets. Our main sample comprises the 10,851 firm tweets that employed one or more of the 133 CSR/sustainability/ESG-focused hashtags. To provide a simple validity check for the ESG hashtag filter, we manually reviewed a random sample of 100 tweets containing ESG-related hashtags. Ninety-seven of these were clearly ESG-related based on full-text review, and the remaining three contained safety or public-service content that is tangentially related to environmental or stakeholder topics. This indicates that the hashtag approach performs well for isolating ESG communications for the purposes of this study. These include commonly used tags such as #ESG (3105 tweets) and #Sustainability (2686 tweets). Table 1 summarizes our sample selection process.

Table 1.

Sample Selection—Tweets.

3.2. Dependent Variables: Reputational Awareness and Favorability

The analyses focus on two dependent variables designed to tap, respectively, the awareness and favorability dimensions of reputational capital. To operationalize the awareness dimension, the variable Retweet Count indicates the number of retweets each firm tweet received.

To operationalize the favorability dimension, we employed a multi-stage supervised machine-learning approach [59,60] to code the sentiment in the public replies to the company tweets. First, the sentiment (negative, neutral, or positive) in 1000 random replies was manually coded. Using the codes in the 1000 hand-coded messages, we then trained a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm to code the remaining replies as having a negative, neutral, or positive sentiment. Accuracy on the SVM-coded binary positive sentiment variable compared to the hand-coded replies was 89%, with a Cohen’s kappa score of 0.817 (κ = 0.817), indicating a high level of inter-coder agreement [61]. Our sentiment analysis process involved three human coders classifying 1000 randomly selected replies as negative, neutral, or positive using a standardized coding scheme. Of these coded tweets, 71% achieved complete agreement across all three coders, 30% had two of three coders agree, and less than 1% showed complete disagreement. Each tweet’s final classification was determined by a majority vote weighted by coder confidence based on past performance. While positive replies are relatively infrequent (6.9% of tweets receive at least one positive reply), this aligns with previous findings on sentiment distribution in corporate social media communications (e.g., [5]) and suggests that achieving positive stakeholder sentiment represents a meaningful distinction between communication tactics. Because the sentiment-coding criteria rely on consistent linguistic cues that are captured efficiently by the TF–IDF and feature-selection pipeline, classifier performance plateaued well before the full set of 1000 hand-coded replies, indicating that this sample size was sufficient for reliable training and validation. In a final step, we collapsed these reply-level data to the firm tweet-level and operationalize the variable Positive Replies as a count of the number of positive replies each firm tweet received. To verify that our metrics capture genuine public engagement rather than merely organizational networking, we conducted a small audit of the accounts interacting with firms’ ESG messages. Examining a random sample of 100 tweets that received retweets or replies, we classified users as either personal or organizational based on profile descriptions, images, and posting patterns. This exploratory check revealed that 88% of accounts engaging with ESG messages were individual users, consistent with our interpretation of these interactions as meaningful indicators of stakeholder awareness and favorability rather than artifacts of business-to-business networking or automated engagement. Detailed model evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, F1, and the confusion matrix, are reported in Supplementary Materials Section S1. Definitions for all variables are provided in the Appendix A.

3.3. Independent Variables: Communicative Tactics

To code the communication tactics, we first conducted a thematic content analysis of a random sample of the companies’ tweets. Following methodological tenets outlined by Miles and Huberman [62] and Strauss and Corbin [63], we analyzed the data inductively to identify communicative features unique to the ESG context on social media. Coding thus involved a multistage, iterative process of cycling back and forth among data, the literature, and emergent conceptual categories [62]. As summarized in Figure 1 and discussed in detail in the Results section, the final coding scheme that emerged included four mutually exclusive information types (disclosure, public education, marketing, and non-informational) and four types of non-mutually exclusive community-building (dialogue, user mention, and stewardship message) and action tactics (mobilizational message). (Our inductive insights were developed by also looking at the 42 ESG-focused Twitter accounts of the 200 largest firms in the Fortune 500 index in 2014. We identified ESG-focused accounts via a qualitative assessment of each of the 200 firms’ Twitter accounts. The account purpose is generally clearly stated in each account’s profile. For example, for GE’s ESG account, @gehealthy, the profile description is “Healthymagination is GE’s innovation catalyst for solving major global health challenges, advancing brain health, enabling healthy cities and more.” Typically, these specialized “CSR/sustainability/ESG” accounts supplement a “general” company account, such as (in GE’s case) @generalelectric.)

Working from the hand-coded set of randomly sampled tweets, we used two broad strategies for coding the remainder of the messages. First, each community-building and action tactic was coded using distinct custom algorithms that were refined until accuracy was above 90 percent. Second, the four information types were coded using supervised machine learning classification using an SVM model. In short, all firm tweets were assigned codes on a series of eight binary variables indicating one of four mutually exclusive information types and four non-mutually exclusive community-building and action tactics. Further details on all eight coding categories—including definitions, boundary criteria, and illustrative examples distinguishing Disclosure from Public Education—are provided in Supplementary Materials Section S2.

3.4. Control Variables

We also control for variables shown to be important predictors of social media outcomes in prior literature [44,64]. Notably, a firm’s time and previous effort on the platform, as well as the number of followers it has accumulated, influence the number of retweets and replies the firm receives. We include three account-level variables to control for these factors: # of Followers indicates the number of Twitter users that follow the organization, Time on Twitter measures the number of days (as of 1 January 2020) since the firm created its Twitter account, and Prior Statuses Count indicates the cumulative number of tweets the firm had sent as of 1 January 2020. It is plausible that, in the social media context, these account-level factors replace traditional “offline” firm-level and industry-level controls. Still, to check this assumption, the analyses also include logged Total Assets and prior year Sales from Compustat and a measure of ESG Risk from Sustainalytics This third-party ESG performance metric provides an independent assessment of each firm’s exposure to material ESG risks and its effectiveness in managing them. By controlling for this measure of actual ESG performance, we can better isolate the effects of communication tactics from underlying ESG activities. We also include sector fixed effects in all regressions.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

In this section we present descriptive statistics for both the control and dependent variables, followed by exploration of the independent variables to address RQ1.

4.1.1. Control Variables

Table 2 contains descriptive statistics and Table 3 a correlation matrix for our main sample. At the account level, the average number of Followers (in 1000 s) was 148.018 (s.d. = 599.817), though this ranged widely from a low of 0.357 to a high of 13,187.786. The average Time on Twitter (in 100 s of days) at the start of 2020 was 45.013 (s.d. = 7.581) and ranged from a low of 10.41 to a high of 57.72. Prior Statuses Count, in logged form, has a mean of 8.921 and a standard deviation of 1.044, with minimum and maximum values of 4.277 and 14.695, respectively, or in non-logged format an average of 15,239 cumulate tweets sent. Average logged Assets (in $ million), in turn, was 10.127, average lagged Sales was 9.511, and lagged ESG Risk was 23.035.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix.

4.1.2. Dependent Variables

The mean for Retweet Count, our proxy for reputational awareness, is 2.132 with a standard deviation of 7.214 and range from 0 to 325 retweets. This indicates substantial variation in the extent to which firm ESG messages generate audience awareness through sharing. Positive Replies, our proxy for reputational favorability, has a mean of 0.069, with a standard deviation of 0.462, and ranges from 0 to 20. These statistics suggest that while retweets are relatively common for ESG messages, receiving positive audience replies is a more selective outcome. This pattern aligns with the understanding that generating favorable sentiment requires more substantial audience engagement than simply prompting message sharing.

4.1.3. RQ1: Eight Communicative Tactics

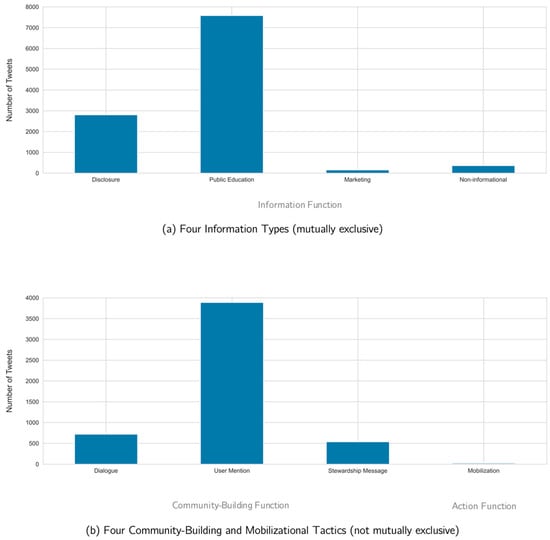

Turning to our findings for RQ1, Figure 2 shows the frequency of the eight tactics we discovered in the 10,851 firm tweets. To start, as shown in Figure 2a, each tweet was characterized as having one of four mutually exclusive information types: disclosure, public education, marketing, or non-informational.

Figure 2.

Frequency of communicative tactics in firms’ ESG messages. Note: Date from coding of 10,851 original ESG-focused tweets sent by S&P 500 Twitter from 2020–2022. Each tweet could be coded as having multiple community-building and/or action tactics but at most one of the mutually exclusive informational tactics. Of the “non-informational” messages, most (but not all) are coded for one of the community-building or mobilizational tactics.

A large proportion (25.7 percent) of tweets (n = 2789) were coded as Disclosure; such messages report information on the firm’s ESG activities. For example, @broadridge sent the following message noting its board diversity efforts:

We’re proud of our commitment to #diversity, #equality and inclusion at all levels. we know first-hand the importance & value of board diversity and we encourage other companies to rise to this moment. #theboardchallenge https://t.co/h8tmatkidi.

The second major type of information, covering 69.6 percent (n = 7552) of tweets, is what we call the Public Education tactic. As with disclosure tweets, public education tweets aim to convey information; however, unlike disclosure tweets, public education messages do not report on the company’s activities but rather seek to educate the public on a topic related to a ESG core area—such as technology, health, education, sustainability, diversity, or the environment—that the company believes will be of interest to its followers. Public education and disclosure constitute two distinct one-way informational tactics. Anything that is informational but reports on the firm’s ESG activities is classified as Disclosure; Public Education messages, in contrast, contain information (including facts, educational material, inspirational messages, etc.) on ESG-related topics that does not relate to the firm’s activities. Public education tactics seem to be a new way of building a positive reputation; similar to related findings that audiences may be built on social media by adopting a niche “expertise” role [65], focused public education efforts may help foster a large network of positively affected followers, thereby enhancing both the awareness and favorability dimensions of reputation. A good example is the following tweet from @msci_inc:

the #nasdaq inc. stock exchange’s new #diversity rules will impose a board diversity disclosure requirements on nasdaq-listed companies. will these mandatory disclosure requirements nudge companies to improve the diversity of their boards? https://t.co/h0z0ftb1ts https://t.co/sxecyhldfu.

The third information type is Marketing, reflecting messages designed to sell products or services. These tweets do not convey information on the company’s ESG-related activities, nor do they present ESG-related information that could educate the public. Marketing messages were rare—occurring in only 1.4 percent (n = 152) of tweets. A good example is the following tweet by @dte_energy marketing its “sustainable” products:

this #earthday and every day, we’re proud to partner with @energystar to deliver cost-saving #energyefficiency solutions that improve air quality and protect the climate. together, we can create a more sustainable future. #energychoicescount https://t.co/tzfkffzfcw.

The final informational category was Non-Informational. Such tweets do not present information. Instead, they pose a question, ask readers to do something, are a response to another tweet, or just thank, mention, or congratulate another Twitter user. Most are coded for one of the community-building or action tactics outlined below. For example, @discover tweeted this message:

@tsahia sounds like a nice place! just be sure to include the hashtags #sweepstakes and #eatitforward for your nomination to count! *keegs

In addition to the four binary variables Disclosure, Public Education, Marketing, and Non-Informational, for additional tests we also created the variable Information to indicate tweets that contain any of the first three types. On this aggregate variable, 96.7 percent (n = 16,190) of tweets received a score of “1,” with the remaining 3.3 percent (n = 358) coded as “0” indicating non-informational messages.

Next, as shown in Figure 2b, we identified four community-building and action tactics. Unlike the information types, these four tactics were not found to be mutually exclusive and thus each tweet could receive a score of “1” on more than one of the variables. To start, there is the higher-level category Community-Building, comprising 43.6 percent (n = 4731) of tweets. There are three specific community-building tactics under this category: Dialogue, User Mention, and Stewardship Message. Tweets coded as Dialogue contain a conversational tactic—typically asking a question, responding to a public query, or engaging in a pre-scheduled, real-time “tweetchat.” An example of a broadly targeted call for dialogue is the following tweet from IBM announcing an upcoming tweetchat:

Pls join the #P4SPchat on citizen engagement. Starts in 45 min, Noon ET http://t.co/GobUBqy3Qe.

In contrast, the following tweet by @amazon is a question targeted at one specific user:

@dannyuseswords thank you for taking the time to share your experience with us! we’re so glad to hear our driver went above and beyond for your delivery.#deliveringsmiles.

In both examples, the tweet reflects engagement in conversational, two-way communication [44] between firm and public consistent with the notion of “dialogic accounting” [10]. We found 6.6 percent (n = 716) of tweets to be dialogic.

The second community-building tactic is the User Mention, found in 35.7 percent (n = 3874) of all tweets. In these messages, the firm employs the @USER feature to mention or “talk about” another Twitter user. For example, the following message from @hesscorporation includes mentions of two organizations, @prairie_grit and @teamminot:

hess recently donated $40,000 to @prairie_grit in our continued support of the minot, nd #community. the donation will be used to increase the clinic size to allow for more therapists, services & expanded insurance coverage options that will include @teamminot military families.

In so doing, the firm is deepening its online ties with the two Twitter users (@prairie_grit, @teamminot). This also provides the opportunity for the firm to increase awareness by reaching users who follow @prairie_grit and @teamminot; as such, it is a method for increasing its influence. The above tweet is an example of a message that contains two tactics: Disclosure, by reporting on the company’s charitable partnerships, and User Mention. As noted earlier, while the informational tactics (disclosure, public education, and marketing) are mutually exclusive, none of the community-building or action-oriented tactics are—multiple such tactics could occur in any one message.

The third community-building tactic is the stewardship message. Stewardship is a relationship cultivation approach identified in the public relations literature [57] in which publicly recognizing, thanking, or expressing gratitude to stakeholders can build loyalty and strengthen or maintain relationships. Accordingly, we coded messages as a Stewardship Message when they congratulated or expressed gratitude to a user or group of users. The following example, sent by @ nisourceinc, is showing gratitude to employees:

thank you to our hard-working #naturalgas employees and all you do to care for the safety and comfort of our communities, every day. #nguwday #gasworkersday #natgas https://t.co/dxegyaejso.

We found 4.9 percent (n = 532) of all tweets contain the Stewardship Message tactic.

The final category is what we call “action” tactics. Comprising the single Mobilizational Message tactic, action tweets were found in only 0.3 percent (n = 33) of all messages. Like dialogic tweets, Mobilization tweets aim to go beyond one-way information. Yet instead of seeking to engage members of the public in dialogue—or, in effect, to say something—mobilizational messages aim to mobilize audience members to do something [44]. The most common mobilizational messages are those asking followers to vote (e.g., in a contest) or to retweet a message, such as the following tweet from @jbhunt360:

we are proud to once again be nominated as a @womenintrucking top company for women to work for in transportation. if you think j.b. hunt is a great place for women to work, then click the link and cast your vote! #womenintransporation #inclusion https://t.co/jgqmhn9crk https://t.co/vz0zblcin8.

While such messages often receive a strong audience response, they are not common in our sample.

4.2. Tests of RQ2

Table 4 presents results from four negative binomial regressions. Our independent variables’ variance inflation factors (VIFs) in these tests remain well below conventional thresholds (all under 3.5, compared to common cutoffs of 5 or 10), indicating that multicollinearity does not substantially affect our parameter estimates or statistical inferences. Model diagnostics confirmed that negative binomial models provided the best fit for both dependent variables. For Retweet Count, the Poisson specification was rejected (χ2 = 172,241, p < 0.001), and zero-inflated models did not improve fit (AIC = 40,666 vs. 39,849; BIC = 40,819 vs. 40,003). For Positive Replies, the Poisson model was again rejected (χ2 = 25,914, p < 0.001), and ZINB models provided only marginally lower AIC (4739 vs. 4810) and BIC (4922 vs. 4963). Negative binomial models were therefore retained as the most appropriate and parsimonious specification. The two dependent variables, Retweet Count, the proxy for reputational awareness, and Positive Replies, the proxy for reputational favorability, are each regressed first on the three higher-level tactical categories Information, Community-Building, and Action (Models 1 and 3) and on the larger set of eight constituent informational, community-building, and action tactics (Models 2 and 4) to examine RQ2a and RQ2b.

Table 4.

Negative Binomial Regressions—Dependent Variables are Reputational Awareness and Favorability.

We first summarize the results for the control variables, which are consistent across the six models: Retweet Count and Positive Replies are associated with messages sent by accounts that have a higher number of followers. Time on Twitter is positively associated with Retweet Count but does not significantly affect Positive Replies. Prior Statuses Count is negatively associated with Retweet Count but positively associated with Positive Replies. For the firm-level controls, we see Size is positively associated with both dependent variables, while Sales is negatively associated with both. ESG Risk is negatively associated with Retweet Count but shows no significant relationship with Positive Replies.

Turning to the key variables of interest—the measures of informational, community-building, and action tactics—we start with a discussion of the regressions on Retweet Count in Models 1–2. Beginning with the informational tactics, the composite variable Information receives a positive and significant coefficient in Model 1, as do Disclosure, Public Education, and Marketing in Model 2. These results indicate that, compared to the baseline category of non-information-focused tweets, messages that include an informational tactic are more likely to receive more retweets from members of the public.

A different pattern occurs with the variables capturing the community-building tactics. In Model 1 the composite variable Community-Building is negatively associated with Retweet Count, as is the constituent variable Dialogue in Model 2. User Mention shows a marginally significant positive relationship with Retweet Count, while Stewardship Message is not significantly related.

For the action category, Mobilizational Message is negatively associated with Retweet Count in both Models 1 and 2, though this relationship is not statistically significant.

We see a different pattern in the regressions for Positive Reply in Models 3–4. The composite variable Information in Model 3 shows a marginal positive association with Positive Replies, but none of the constituent information tactics (Disclosure, Public Education, or Marketing) in Model 4 obtain a significant relationship.

Several community-building tactics, however, do obtain significance, yet here some of the signs differ from what was seen in Models 1–2. The composite variable Community-Building does not show a significant relationship with Positive Replies in Model 3. However, in Model 4, User Mention is positively and significantly related to Positive Replies, while Dialogue is negatively related. Stewardship Message shows a marginally positive association with Positive Replies.

The action tactic Mobilizational Message fails to obtain significance in either model predicting Positive Replies.

In summary, the results suggest that informational tactics are generally associated with increased reputational awareness (greater retweet counts), while community-building tactics show a more complex relationship. Dialogue tends to reduce both retweet counts and positive replies, while User Mention enhances both metrics. Stewardship Message appears to have a marginally positive effect only on reputational favorability. The action tactic Mobilizational Message does not show significant effects on either dimension of reputational capital in this analysis. Overall, firms appear to face important trade-offs in their communication strategies, as tactics that maximize message spread may not necessarily generate the most favorable sentiment, and vice versa. Understanding these dynamics allows firms to tailor their approach based on specific reputational objectives.

4.3. RQ3: Testing Interactions with Disclosure

To test RQ3, Table 5 adds to the previous models a series of variables interacting Disclosure with each of the community-building and action tactics. Models 1 and 3 examine these interaction effects using the higher-level ICA categories, while Models 2 and 4 examine interactions with the specific constituent tactics.

Table 5.

Interactions with Disclosure—Dependent Variables are Reputational Awareness and Favorability.

Starting with reputational awareness (Retweet Count) in Models 1 and 2, we find interesting conditioning effects. In Model 1, the interaction between Disclosure and Community-Building is negative and significant, indicating that when disclosure is combined with community-building tactics, the positive association of disclosure with retweets is diminished. When looking at specific tactics in Model 2, the interaction Disclosure × User Mention becomes insignificant, suggesting when the targeted audience is restricted in scope, the message is less likely to be retweeted. Also, the interaction term Disclosure × Stewardship Message obtains a significant negative association, indicating that tweets combining disclosure with stewardship messages are less likely to receive retweets than disclosure-only tweets.

In contrast, the coefficient on Disclosure × Mobilizational Message is positive and significant in both Models 1 and 2; this indicates that tweets combining disclosure with mobilizational content are substantially more likely to receive retweets than tweets with only disclosure. The magnitude of this effect (coefficient of 1.50 in Model 1 and 1.39 in Model 2) suggests this combination is particularly powerful for generating message sharing.

Turning to reputational favorability (Positive Replies) in Models 3 and 4, we observe a different pattern of results. The interaction between Disclosure and Community-Building in Model 3 is not significant, suggesting no overall conditioning effect of community-building tactics on disclosure’s relationship with positive replies. Looking at the specific tactics in Model 4, neither Disclosure × Dialogue, Disclosure × User Mention, nor Disclosure × Stewardship Message obtains significance, indicating these community-building tactics do not significantly moderate the relationship between disclosure and reputational favorability.

The interaction between Disclosure and Mobilizational Message also fails to reach significance in both Models 3 and 4, though this may be partly due to the limited number of tweets employing the mobilizational tactic (only 0.3% of the sample). Because mobilizational messages make up only 0.3 percent of ESG tweets in our sample, these results should be read as illustrating the potential amplification that such calls to action can generate when they are used, rather than as reflecting a common feature of firms’ ESG communication portfolios. Relatedly, the coefficients and standard errors for mobilizational terms in the favorability models (Table 5, Models 3–4) are inflated due to the extremely low frequency of mobilizational messages and positive replies. This data sparsity produces quasi-complete separation in estimation rather than a reporting error. The pattern reinforces that mobilizational disclosures amplify diffusion (retweets) but have little consistent effect on audience favorability.

Collectively, these tests suggest that the combination of disclosure with various communication tactics has more pronounced effects on reputational awareness than on reputational favorability. The most notable finding is that combining disclosure with mobilizational messages substantially enhances the likelihood of message sharing, while combining disclosure with stewardship messages reduces it. This suggests that when firms disclose ESG information, adding a call to action significantly boosts audience sharing, while expressions of gratitude may detract from the message’s “shareability.” For reputational favorability, however, these interaction effects appear less consequential.

4.4. Additional Analyses

Examination of the core research questions raises several issues worth further investigation. In this section we report two sets of additional analyses that provide further insights into our findings. First, we examine the generalizability of our framework to a broader sample of all S&P 500 tweets beyond those focused specifically on ESG. Second, we investigate how firm type (B2C versus B2B) influences the relationship between communication tactics and the accumulation of reputational capital. These analyses help us better understand how the communication framework and tactics we identified might function in different contexts and for different types of companies.

4.4.1. Generalizability to All S&P 500 Tweets

To further explore the generalizability of our findings, we conducted additional analyses on the full set of 2,309,573 firm tweets, rather than restricting our tests to the 10,851 ESG-focused tweets. While our prior analyses examined the subset of tweets explicitly discussing CSR, sustainability, or ESG topics, this broader analysis allows us to assess whether the communication tactics identified in our study are associated with audience engagement across all corporate messaging, regardless of topic. By including all firm tweets, we can evaluate whether the relationships between information-sharing, community-building, action-based tactics and reputational capital hold when considering a more comprehensive view of corporate social media strategy.

Table 6 replicates our main regressions for the full sample of S&P 500 tweets. Looking at the reputational awareness tests (Retweet Count) in the full sample of 2,309,573 tweets in Model 1 of Table 6, we see that Information is positively associated with Retweet Count with a coefficient of 1.54, which is considerably stronger than what we observed in our ESG-focused sample. Interestingly, Community-Building obtains a significant negative coefficient of −1.78, which is also substantially larger in magnitude than in our main analysis. Mobilizational Message shows a positive relationship with retweets (coefficient of 1.01), contrary to the negative but non-significant relationship found in our ESG-focused sample.

Table 6.

All S&P 500 Firm Tweets—Dependent Variables are Reputational Awareness and Favorability.

For reputational favorability (Positive Replies) in Model 3, we find that Information obtains a significant positive association (coefficient of 0.03) with the odds of receiving positive replies. This contrasts with our ESG-focused sample where this relationship was only marginally significant. More notably, Community-Building shows a significant negative relationship with Positive Replies (coefficient of −1.36), which differs markedly from the non-significant positive relationship in our main analysis. Mobilizational Message displays a significant positive relationship (coefficient of 0.87) with positive replies, unlike the non-significant relationship in our ESG-focused sample.

These differences in results between our ESG-focused sample and the broader dataset of all corporate tweets suggest that audience responses to communication tactics vary substantially depending on the content domain. The general public appears to respond differently to information-sharing, community-building, and action-oriented tactics when they appear in general corporate communication versus specifically in ESG messaging.

Our key takeaway here is that audience context matters. A follower base interested in learning about a company’s CSR, sustainability, and ESG engagement efforts appears to respond favorably to different types of firm messages than audiences following a Twitter account to learn about products or company performance. While our main inferences regarding divergent reputation-building responses to different communicative tactics remain valid, these findings call for future research into the influence of audience characteristics and expectations when engaging with different types of corporate content.

4.4.2. B2C vs. B2B Firms

To better understand how firm type might influence audience reactions to ESG communication tactics, we conducted a supplementary analysis separating the B2C (business-to-consumer) firms from B2B (business-to-business) firms. Based on a review of SIC codes and revenue streams as in Srinivasan et al. [66], we classify 15% of the firms in our sample as B2C firms, 60.5% as B2B firms, and the remainder as a mix. Table 7 presents the results, with Models 1–4 examining reputational awareness and Models 5–8 examining reputational favorability.

Table 7.

CSR Tweets Separated by B2C and B2B Firms—Dependent Variables are Reputational Awareness and Favorability.

The analysis reveals differences in how communication tactics affect reputation-building between these firm types. Looking first at reputational awareness, Models 1–2 show that informational tactics have a much stronger positive association with retweets for B2C firms (coefficient = 1.63, p < 0.01) than for B2B firms (coefficient = 0.18, non-significant). This suggests that consumers are particularly responsive to ESG-related informational content, while business audiences appear less affected by such tactics.

Community-building tactics show a marginally significant negative effect on retweets for B2C firms (coefficient = −0.15, p < 0.10) and a stronger negative effect for B2B firms (coefficient = −0.10, p < 0.01). When examining specific tactics in Models 3–4, we find that dialogue has a substantial negative association with retweets for both firm types, though the effect is considerably stronger for B2C firms (coefficient = −3.40, p < 0.01) compared to B2B firms (coefficient = −1.33, p < 0.01).

Mobilizational messages show a significant negative association with retweets for B2C firms (coefficient = −1.59, p < 0.05) but no significant effect for B2B firms, suggesting that calls to action may be viewed differently by consumer audiences versus business audiences.

For reputational favorability, the differences are even more pronounced. Information tactics show a strong positive association with positive replies for B2C firms (coefficient = 1.64, p < 0.01) but no significant relationship for B2B firms. This pattern reinforces the finding that consumer audiences are more responsive to informational ESG content than business audiences.

Dialogue tactics show strong negative associations with positive replies for both firm types in Models 7–8. However, the effect is again more pronounced for B2C firms (coefficient = −2.71, p < 0.01) than for B2B firms (coefficient = −0.73, p < 0.05). Interestingly, user mentions have a significant positive association with positive replies for both B2C firms (coefficient = 0.60, p < 0.05) and B2B firms (coefficient = 0.24, p < 0.10), though the effect is stronger for B2C firms.

These findings highlight the importance of tailoring ESG communication strategies to specific audience types. B2C firms appear to benefit more from informational tactics when building reputation among their consumer-oriented audiences, while both firm types need to be cautious about dialogue-based approaches, which consistently show negative associations with both reputational awareness and favorability. The results reinforce our earlier observation that audience context is a critical factor in determining the effectiveness of ESG communication tactics.

4.5. Robustness Tests

We conducted comprehensive robustness testing to validate our findings across multiple specifications. First, we employed dependent variable transformations to ensure our results weren’t sensitive to the operational definition of reputational capital. Specifically, we ran alternative versions of our four main tests from Table 4 using logit regression on binary versions of our dependent variables, with Retweeted indicating tweets that received at least one retweet (59.68% of ESG tweets) and Positive Reply indicating tweets that received at least one positive reply (4.66% of ESG tweets). This approach tests whether the drivers of any engagement differ from those driving the volume of engagement. The signs for all variables across the four models are identical to what was seen in Table 4, confirming the directional consistency of our findings. We also assessed whether continuous proportion-positive and net-sentiment measures of reputational favorability altered the substantive conclusions; both yielded results for the ICA variables that closely align with those reported in Table 4 (see Supplementary Materials Table S3).

Second, we applied alternative regression methods beyond our primary negative binomial approach, including zero-inflated models and versions of the main tests with firm fixed effects and with combined firm and year–month fixed effects, to address both distributional and unobserved-heterogeneity concerns. Across these additional specifications, the signs and relative magnitudes of the ICA coefficients were similar to those in Table 4, although standard errors increased and some coefficients lost statistical significance, consistent with the reduced efficiency of the fixed-effects models given the sparsity of several tactics within firms. Third, we implemented the Impact Threshold for a Confounding Variable method [67] to quantify the strength of potential omitted variables needed to invalidate our inferences, confirming the resilience of our results to unobserved factors. We further augmented our models with additional controls at both the message and firm levels. At the message level, we incorporated tweet characteristics including character count, multimedia elements (photos), and hyperlink inclusion (URLs). At the firm level, we added controls for organizational scale (number of employees) and ownership structure (percentage of institutional ownership), among others. Across all these alternative specifications, the directional relationships between our communication tactics and reputational capital measures remained consistent, with no sign reversals for any key coefficients. While significance levels occasionally fluctuated for specific tactics across some models, the overall pattern of results remained stable, lending strong support to the robustness of our communication framework and its relationship to reputational capital accumulation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study was built around two key assumptions: (1) the reporting practice of ESG disclosure can be meaningfully expanded to ESG communication; and (2) that the amount of reputational capital acquired by any given firm is contingent on the specific communicative tactics employed. Inductive analyses of firms’ ESG tweets identified four mutually exclusive information types. A large proportion (25.7 percent) of messages, as might be expected, conveyed disclosure. While marketing messages were rare, a large proportion (69.6 percent)—in fact, the majority of messages—were classified as public education and only 3.3 percent as non-informational. We also identified four non-mutually exclusive community-building and action tactics that could be used in conjunction with or separately from the four information types. Three of these tactics (dialogue, user mentions, and stewardship) were community-building focused, while the fourth (mobilizational messages) was action-oriented. In responding to calls to push ESG reporting studies beyond the predominant focus on disclosure [5,7,10,12,20,68,69], our findings strongly suggest a focus on disclosure does not do justice to firms’ ESG reporting and communication efforts. The typical firm studied here does not just use social media to disclose its ESG activities but is assuming an ESG information/knowledge-focused “public education” role, engaging in dialogue around ESG issues with multiple stakeholders, and employing a number of community-building tactics to deepen and strengthen ties with constituents.

Our multivariate analyses revealed that reputational awareness appears to be associated with the use of information provision and, to a lesser extent, community-building tactics. Reputational favorability, in turn, is more closely related to the use of community-building tactics. Interestingly, Community-Building, driven chiefly by the role of Dialogue, though not significantly related to reputational favorability, is negatively related to reputational awareness. In hindsight this makes some sense: dialogue’s close engagement of a smaller subset of stakeholders may make it more likely to spur favorable, positive replies from those directly involved, but these conversations do not appear to be “retweetable” for those not engaged in the discussion. Our tests of the conditioning effects of disclosure for RQ3, meanwhile, suggest that disclosure has a bigger impact when it is paired with mobilizational messages—a key action tactic—and a smaller impact when paired with stewardship messages, a community-building tactic. Because mobilizational tweets often contain explicit sharing prompts (e.g., “please retweet”), part of this effect may reflect mechanical message amplification rather than reputational engagement per se. Collectively, our tests strongly suggest that firms’ ESG messaging goes well beyond disclosure, and that disclosure—the core variable, for better or worse, studied in the ESG literature in accounting—appears to have its strongest relationship to firms’ reputational awareness when paired with action-oriented tactics.

The reason for this is likely found in the link to reputation. If, as KPMG International [70] has suggested, the “business imperative” driving ESG reporting is reputation, then we are not dealing with an investor-driven nor information-driven phenomenon. Instead, we are dealing chiefly with firms’ efforts to change public perceptions. And reputations are changed not just through the provision of different types of information but by a suite of communicative tactics that are better suited to the network-building and relationship-building that communication scholars have shown to be key to the spread of ideas, opinions, and perceptions [44,47].

These patterns also vary by audience type. B2C firms—addressing broad consumer publics—are gaining reputational awareness from informational transparency. By contrast, B2B firms appear to derive greater reputational value from marketing and user-mention strategies that are designed to increase visibility and foster relationships with their narrow audience. This segmentation underscores the importance of aligning ESG communication strategies with audience composition and engagement expectations.

Our additional analyses examining both the full corpus of 2.3 million corporate tweets and the comparison between B2C and B2B firms further emphasize the critical role of audience and firm context in shaping communication effectiveness. We found that general corporate messaging elicits different response patterns than ESG-specific content, suggesting audience expectations vary by content domain. Similarly, B2C firms with consumer-facing audiences see substantially stronger effects from informational tactics on both reputational awareness and favorability compared to B2B firms. These findings suggest there is room in the dialogic accounting [10], accountability [23], and stakeholder engagement [55] literature to further emphasize the role of audience composition and expectations. In conceptualizing reputational changes as a function of audience reactions, the study also helps address concerns that “how relevant publics respond to CSR disclosure strategies remains relatively under-explored” (p. 55 [5]).

Future research could explore how the accumulation of reputational capital through ESG communication affects tangible firm outcomes. Preliminary evidence suggests that firms effective at building reputational capital through their ESG communications may experience benefits such as enhanced social media followership, improved sales performance, and better sustainability rankings. For instance, firms with higher levels of audience engagement on their ESG communications might experience faster growth in their social media audience, potentially creating a virtuous cycle that amplifies their future communications. Similarly, effective ESG communication might positively influence consumer purchasing decisions, potentially leading to improved sales performance. Future studies could attempt to establish causal relationships between social media-based reputational capital and such outcomes.

Another promising avenue for future research involves examining how audience size and network characteristics moderate the effectiveness of different communication tactics. While our study identified which tactics are most effective overall, the impact of these tactics likely varies based on a firm’s follower count, network density, and audience composition. Future research could investigate whether the optimal communication mix changes as a firm’s social media audience grows or as the composition of that audience shifts. For example, certain community-building tactics might be more effective for firms with smaller, more engaged audiences, while informational tactics might provide greater benefit to firms with larger follower counts. Understanding these dynamics would provide valuable insights for firms seeking to optimize their ESG communication strategies across different stages of audience development.

We should also be aware that in the newly identified communication tactics we may be seeing a convergence of firms’ ESG and corporate political activity (CPA) goals. Notably, like disclosure, public education is an established “informational” strategy for achieving long-term policy goals, while community-building tactics can be seen as consistent with what Hillman and Hitt [71] call the “constituency-building” CPA strategy, or ways of building an online constituency of followers that can eventually be mobilized to support the company’s policy agenda. Social media thus helps firms utilize a relationship-building approach to reputation change and an analogous relational approach [71] to CPA. This overlap between firms’ reputation-building and CPA strategies is worth further exploration.

Post hoc analyses also suggest audience characteristics and firm type strongly relate to how communication tactics translate into reputational capital. Different types of firms—particularly B2C versus B2B companies—appear to experience different returns on their ESG communication investments. These findings suggest the benefits that accrue to firms using social media to accumulate reputational capital are contingent on audience expectations and composition. Future research could verify these benefits and also dig into the costs associated with these efforts. While social media platforms themselves are free to adopt, the staff expenditures required to run a professional, cross-functional social media strategy are not insignificant. Beyond the monetary costs are the reputational risks generated by engagement on social media [72]. These risks can come not only in the form of a firm’s own communicative mis-steps but from decentralized, bottom-up and “viral” campaigns from disaffected publics, activist stakeholders, and other stakeholders [12]. Further research could examine how firms’ informational and communicative social media tactics change—and with what effect—in response to crises and other reputational risks [14].

More broadly, this study’s focus on ESG communication, rather than formal reporting, underscores a shift from regulated, assured disclosure to dynamic, strategic interaction. While communication tactics such as dialogue and mobilization expand stakeholder reach and immediacy, they also pose challenges for comparability and verification. The coexistence of disclosure- and marketing-oriented messages highlights tensions between transparency and persuasion, raising potential concerns about selective framing and greenwashing [73]. Recognizing this distinction clarifies how social-media communication complements—but does not substitute for—formal reporting in shaping perceptions of corporate accountability.

While our study provides valuable insights into ESG communication tactics and reputational capital, several limitations of our approach suggest important avenues for future research. First, while our analyses establish significant associations between communication tactics and reputational outcomes, we cannot claim direct causality nor fully rule out endogeneity concerns. The relationship between ESG communication and reputation-building is complex and potentially bidirectional, with firms’ existing reputations likely influencing how their messages are received. Moreover, specific structural features within messages may elicit different audience responses; for example, messages designed to prompt replies may generate different reaction patterns than those focused on disclosing donation activities. Second, our operationalization of reputational capital through retweets and positive replies, while empirically grounded, represents a proxy measure that captures only certain dimensions of this multifaceted construct. Future studies could triangulate these social media metrics with traditional reputation measures to validate their relationship with broader reputational outcomes. Third, our sentiment analysis approach, while validated, may not fully capture sarcasm, cultural nuance, or implicit meanings in replies—limitations common in computational text analysis. Relatedly, exploring mixed or polarized audience reactions could yield deeper insights into how stakeholders process ESG messages, as some tactics may simultaneously attract support and skepticism. This dovetails with the point that our measure of reputational favorability, operationalized as the count of positive replies, captures only one dimension of stakeholder sentiment and does not incorporate the relative frequency of neutral or negative responses. Fourth, our ESG tweet identification strategy, which relies on high-frequency hashtags, offers efficiency and precision but may exclude rare or firm-specific ESG content that does not use these tags. Future work could explore hybrid approaches combining rule-based filters with semantic or embedding-based classifiers to expand coverage. Finally, longitudinal changes in firms’ social media strategies represent an important direction for future research, particularly in understanding how organizations adjust their ESG communication following reputational shifts or crises.

In showing how reputational capital can be accumulated on a micro, message-by-message, day-to-day level through engagement with the public, the paper not only suggests ways that a core intangible “capital” can be tracked, but also how that asset fits in a communication-driven value chain. Our findings suggest a model encompassing communicative inputs categorized by the Information–Community–Action framework, reputational outputs measured through audience engagement, and potential firm-level outcomes. This model could be fleshed out to provide insights for management’s decision-making processes by identifying the social media communication tactics firms could employ to effectively communicate with stakeholders to foster the accumulation of reputational capital and, in turn, contribute to the firm’s financial as well as sustainability objectives. By examining the publics’ reactions to ESG communication on social media, firms could also identify additional information to be included in their reports. Our findings also illustrate how firms, through interactive communication, can establish a connection between external reporting initiatives and internal management. Ultimately, the connected, targeted, public, and dynamic nature of social media-based communication carries implications for ESG. Building a stakeholder audience matters and communication is key to successful and accountable engagement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/info16121063/s1, ESG Communication Tactics and Reputational Capital.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A., G.M., G.D.S. and S.Z.; methodology, T.A., G.M., G.D.S. and S.Z.; validation, T.A., G.M., G.D.S. and S.Z.; formal analysis, T.A., G.D.S. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A., G.M., G.D.S. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.A., G.M., G.D.S. and S.Z.; visualization, G.D.S. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Schulich School of Business.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The raw data includes social media posts, and Twitter/X restricts those posts from being uploaded to another site. We would be happy to post the regression data or any data that does not include the full tweets.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank seminar participants at York University and the AIS Mid-Year Meeting along with Dean Neu, Jeff Everett, Giri Kanagaretman, Den Patten, Nelson Waweru, Chao Guo, Michelle Benson, Giovanna Michelon, Marion Brivot, and Lina Gomez for helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Variable Definitions

Table A1.

Variable Definitions.

Table A1.

Variable Definitions.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variables REPUTATIONAL AWARENESS Retweet Count | The number of retweets each firm tweet received |

| REPUTATIONAL FAVORABILITY Positive Replies | The number of positive replies each firm tweet received |

| Independent Variables INFORMATION | Tweet coded as containing a disclosure, public education, or marketing tactic (0, 1) |

| Disclosure | Tweet discloses information on firm’s ESG activities (0, 1) |

| Public Education | Tweet contains information intended to educate public on ESG-related issue (0, 1) |

| Marketing | Tweet contains information marketing the company’s products or services (0, 1) |

| Non-Informational | Tweet conveys no information (0, 1) |

| COMMUNITY-BUILDING | Tweet contains dialogue and/or mobilization tactic (0, 1) |