Release of the Fourth Season of Money Heist: Analysis of Its Social Audience on Twitter during Lockdown in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Comparing the release in social media of seasons 3 and 4 of the series in question.

- Quantifying the number of tweets, likes, and replies of Money Heist account during the first month after the release of the third and fourth seasons of the series.

- Analyzing the audiovisual content of these tweets.

- Identifying the most used keywords.

- Identifying the most commonly used keywords that directly or indirectly refer to the lockdown.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Coronavirus, Television, and Platforms

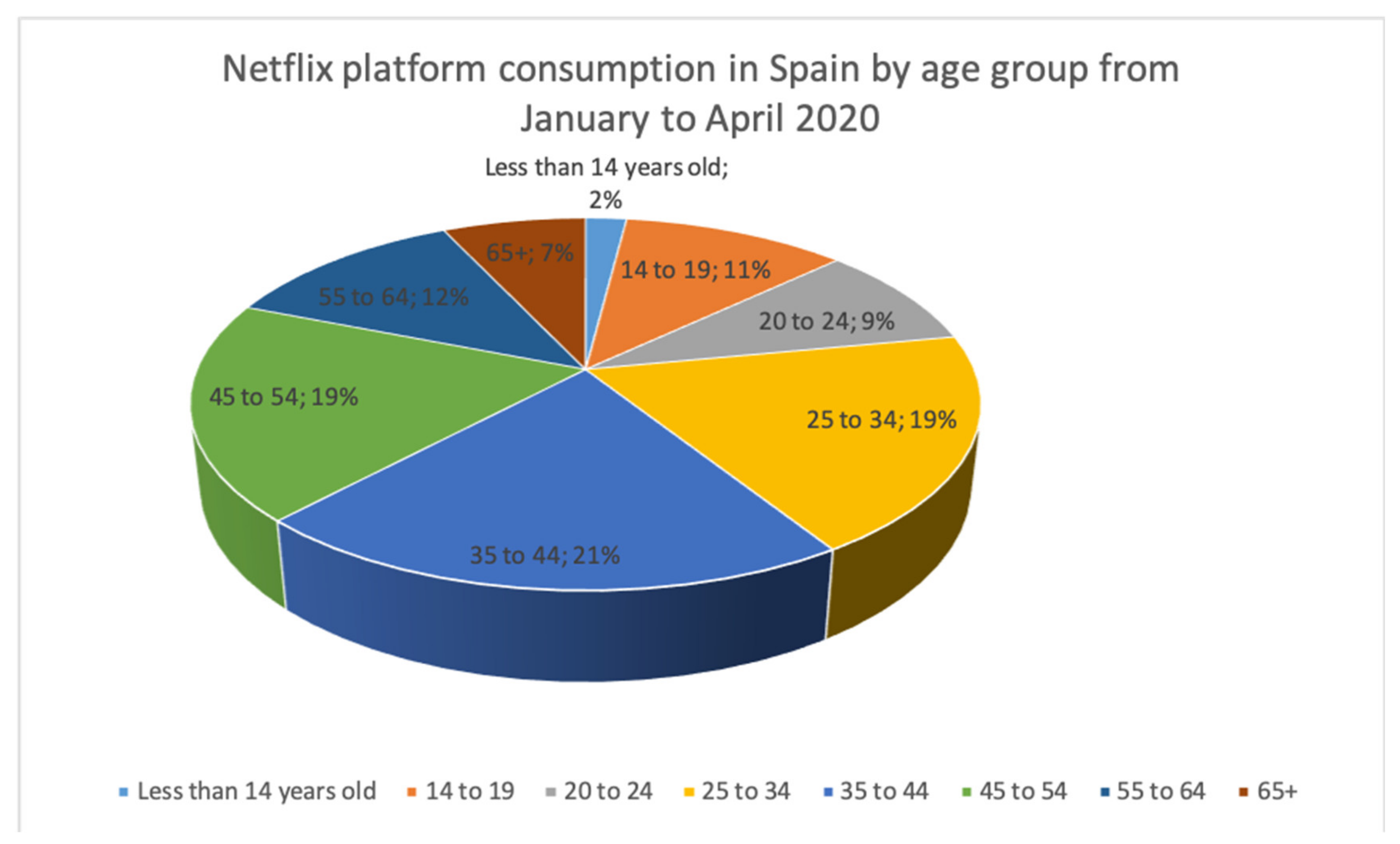

2.2. Netflix and Fiction Series in Spain

2.3. Money Heist

2.4. The Use of the Internet and Social Media during Lockdown

Twitter During the Lockdown

2.5. Transmedia Communication Strategy

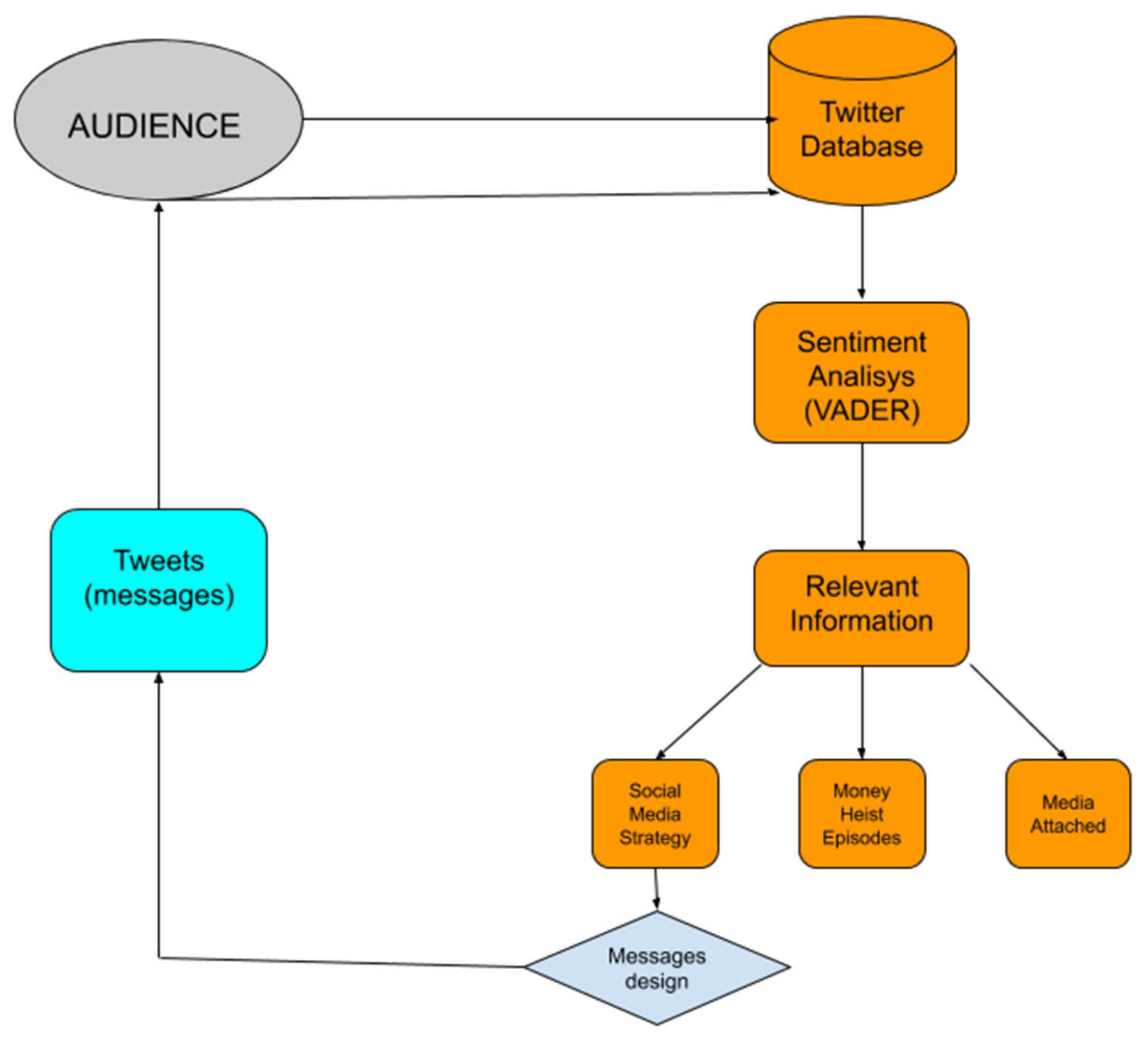

3. Materials and Methods

- ID: it indicates the URL of the tweet.

- screen_name: it indicates the username of the account that posted the tweet.

- created_at: it indicates the date and time of posting of the tweet.

- fav: it indicates the number of times the tweet was marked as a favorite.

- rt: it indicates the number of times the tweet was retweeted.

- RTed: it indicates if the post is a retweet from another account and, if so, indicates from which account.

- text: it shows the text of the post, including hashtags and URLs.

- media: it shows up to four columns, with the URLs of pictures and videos attached to the post.

- Sentiment: it is divided into four columns where an algorithm classifies the messages, depending on if they are positive, negative, or neutral, and adds them a value named Compound.

- Date of tweet

- Number of likes

- Number of retweets

- Number of replies

- Full text

- Number of multimedia links

- Keywords referring to lockdown.

- Content of tweet: If it is a retweet, if it is about the content of the series, about the characters, if it is advertising.

- Emotional component: positive, negative, and neutral

4. Results

4.1. Results of Content Analysis

4.2. Results of the Interviews

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Transmedia strategies must be included in the initial marketing and communication strategy concept. They are, nowadays, a basic element.

- These strategies must be based on different languages and different platforms. It is not only a question of transmitting the same message with the same language on different platforms

- Even the strategy within the same social network, such as Twitter, should not be univocal. The different audiovisual languages must be understood in order to develop strategies in those languages that are considered relevant: video, audio, photos, gifs, or tweet threads.

- In the specific case of Twitter, the dialogue can be improved. The creation of accounts related to characters that interact with each other and with the main user will make the transmedia strategy more realistic.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barlovento Comunicación. Balance del Consumo de Televisión Durante el Estado de Alarma. Available online: https://bit.ly/3fMBMnZ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Martínez, A. Los medios de Comunicación y la Sociedad de la Información. Available online: https://bit.ly/34Zl813 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Blanes, P.; Cadena Ser. HBO es la Plataforma que más Crece en el Confinamiento y Netflix la más Vista en la Cuarentena. Available online: https://bit.ly/2CfwPpO (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Solomando, S.; (Screenwriter, Málaga, Spain). Personal Communication, 2020.

- Romero, J. Coronavirus Superestrella. El Impacto del Covid-19 en la Sociedad a través de los Medios de Comunicación. Available online: https://bit.ly/2DU6Uo0 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Ojer Goñi, T.; Capapé, E. Nuevos Modelos de Negocio en la Distribución de Contenidos Audiovisuales: El Caso de Netflix. Available online: http://www.revistacomunicacion.org/pdf/n10/mesa1/015.Nuevos_modelos_de_negocio_en_la_distribucion_de_contenidos_audiovisuales-el_caso_de_Netflix.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Barlovento Comunicación. OTT y Plataformas de Pago en España. Available online: https://bit.ly/33LHaVN (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Entrega de Resultados EGM 1ª ola 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/2XMyr1Q (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Tyler, A. Análisis de la Representación de la Mujer en la Serie las Chicas del Cable (Netflix 2017-20xx). Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books/about/AN%C3%81LISIS_DE_LA_REPRESENTACI%C3%93N_DE_LA_MU.html?id=Z-TcxgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Quintas, J.; (Cinema Director, Málaga, Spain). Personal Communication, 2020.

- Carrillo, J.; Paradigma Netflix. El Entretenimiento de Algoritmo. Available online: http://www.elboomeran.com/upload/ficheros/obras/paradigmanetflix_extracto.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Atresmedia y Netflix Cierran un Acuerdo sin Precedentes en España para la Producción Internacional de Una Nueva Temporada de ‘La Casa de Papel’. Available online: https://www.panoramaaudiovisual.com/zh/2018/04/18/atresmedia-netflix-nueva-temporada-casa-de-papel/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Rebollo-Bueno, S. Ficción Televisiva y Contrahegemonía: Análisis de La Casa de Papel y Vis a Vis. In Cultura de Masas (Serializada); Donstrup, M., Ed.; Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/87611 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Novendri, R.; Callista, A.S.; Patrama, D.N.; Puspita, C.E. Sentiment Analysis of YouTube Movie Trailer Comments Using Naïve Bayes. Bull. Comput. Sci. Electr. Eng. 2020, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimferrer, S. Netflix Informa ‘a su Manera’ de las Audiencias de ‘La Casa de Papel’. La Vanguardia. Available online: https://bit.ly/3oCv8oR (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- OBITEL. Modelos de Distribución de la Televisión por Internet: Actores, Tecnologías, Estrategias. Available online: https://bit.ly/370ObTS (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Giraldo Cuéllar, J.S.; Ospina Echeverri, J.P. Análisis del Uso táctico del Meme en la Estrategia Publicitaria de Netflix para la Tercera Temporada de la Serie” La Casa de Papel”. Available online: https://red.uao.edu.co/bitstream/10614/12371/6/T09221.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Ripoll, C.; Rodríguez, J. Un Atraco a la Realidad: Análisis de Reconocimiento de Discursos Populares Alrededor de La Casa de Papel. Available online: http://repositorio.udesa.edu.ar/jspui/bitstream/10908/16628/1/%5BP%5D%5BW%5D%20T.L.%20Com.%20Ripoll%2C%20Camila%20y%20Rodr%C3%ADguez%2C%20Jeanette.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Mastandrea, P.; Martínez, D. El lugar de la mujer en la serie La Casa de Papel. Una revisión de estereotipos que insisten. Anuario de Investigaciones de la Facultad de Psicología 2019, 4, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- González Rosero, P.A. Análisis del discurso en la serie La Casa de Papel como cuestionamiento al status quo del sistema democrático. ComHumanitas Rev. Cient. Comun. 2019, 10, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, J. La Música en las Casas: Musicalizations in La Casa de Papel and La casa de las flores and Netflix’s Global Audience. Am. Music 2019, 37, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagello, F. Images of the European Crisis: Populism and Contemporary Crime TV Series. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-review/article/abs/images-of-the-european-crisis-populism-and-contemporary-crime-tv-series/8B4F1C1FEC7E6AD98C38E7DC6F26E159 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Matos, M.A.D. A interpretacao das cores na paratraducao de paratextis audiovisuais-o vermelho na série La Casa de Papel. Trab. Linguística Apl. 2020, 59, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.P. A gestão de Pessoas: Bm Estudo a Partir da Análise da Série La Casa de Papel. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Uberlandia, Brazil, 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.ufu.br/handle/123456789/27797 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Bordin, D.; Baffi-Bonvino, M. Considerações Arespeito do Léxico Tabu na Tradução de Los Mares del sur e La Casa de Papel no par Linguístico Espanhol-Inglês. Available online: https://bit.ly/3jSeP5s (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Karageorgiou, Z.; Mavrommati, E.; Fotaris, P. Escape Room Design as a Game-Based Learning Process for STEAM Education. In Proceedings of the ECGBL 2019 13th European Conference on Game-Based Learning, Elbæk, Lars, Odense, Denmark, 3–4 October 2019; Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited: Reading, UK, 2019; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Castelló-Martínez, A. Análisis del Brand Placement en La Casa de Papel. Ámbitos Revista Internacional de Comunicación. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2020.i48.12 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Telefónica. Telefónica Registra Durante la Crisis del Covid-19 un Crecimiento en su tráfico de Internet Equivalente al de Todo el Año Pasado. Available online: https://bit.ly/3iyxkuv (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Nielsen Media. 3 de Abril de 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/2ChBIij (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Qustodio. Los Menores Españoles Pasan un 80% Más de Tiempo Conectados Durante el Confinamiento en Horario Escolar. Available online: https://bit.ly/3kxad5x (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Cachia, R.; Compañó, R.; Da Costa, O. Grasping the potential of online social networks for foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2007, 74, 1179–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.; Martinez, M.G. Social Media: A Tool for Open Innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkova, M.; Alhakamy, A.; Cafaro, F.; Vedak, S.; Mallappa, R.; Kankara, S.R. Exploring Casual COVID-19 Data Visualizations on Twitter: Topics and Challenges. Informatics 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Twersky, S.; Ignace, K.; Zhao, M.; Purandare, R.; Bennett-Jones, B.; Weaver, S.R. Constructing and Communicating COVID-19 Stigma on Twitter: A Content Analysis of Tweets during the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gencoglu, O.; Gruber, M. Causal Modeling of Twitter Activity during COVID-19. Computation 2020, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Sánchez-Núñez, P.; Peláez, J.I. Sentiment Analysis and Emotion Understanding during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain and Its Impact on Digital Ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Medina, I.; Miquel-Segarra, S.; Navarro-Beltrá, M. El Uso De Twitter En Las Marcas De Moda. Marcas De Lujo Frente a Marcas Low-Cost. Available online: https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0719-367X2018000100055 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Cristófol, F.J.; Aramendia, G.Z.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J. Effects of Social Media on Enotourism. Two Cases Study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarreño-Aramendia, G.; Cristòfol, F.J.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J.; Ginesta, X. Social-Media Analysis for Disaster Prevention: Forest Fire in Artenara and Valleseco, Canary Islands. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țuclea, C.-E.; Vrânceanu, D.-M.; Năstase, C.-E. The Role of Social Media in Health Safety Evaluation of a Tourism Destination throughout the Travel Planning Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.-A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Alt, M.-A. Social Media Goes Green—The Impact of Social Media on Green Cosmetics Purchase Motivation and Intention. Information 2020, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, M.; Ștefănescu, L.; Ozunu, A. Keep Them Engaged: Romanian County Inspectorates for Emergency Situations’ Facebook Usage for Disaster Risk Communication and Beyond. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navalón, J.G.; Gelashvili, V.; Debasa, F. The Impact of Restaurant Social Media on Environmental Sustainability: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sierra, N.; Mondelo-González, E.; Puebla-Martínez, B. Adaptación del Universo de La Casa de Papel a Juegos y Aplicaciones móviles. Available online: https://conferences.eagora.org/index.php/imagen/VISUAL-2020/paper/view/11247 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Formoso, F.; Videla-Rodríguez, J.-J.; García-Torre, M.; Marta-Lazo, C. Análisis de la Producción Web de las Series Españolas Emitidas en Canales Generalistas; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C.J.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rayarel, K. The Impact of Donald Trump’s Tweets on Financial Markets. Available online: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/economics/documents/research-first/krishan-rayarel.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación: La Búsqueda de Significados; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olaz, A. La Entrevista en Profundidad: Justificación Metodoloógica y Guía de Actuación Praáctica; Septem Ediciones: Oviedo, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Tarodo, A. Employer Branding: Un Estudio Sobre la Construcción de la Marca del Empleador. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- B.A. Una Extremeña en la Trama Española Más Internacional. Diario Hoy Extremadura. Available online: https://bit.ly/3kuxyEW (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Moreno, M. El uso de Redes Sociales Crece un 15% en España Durante el Confinamiento. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gMpfSt (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Jenkins, H.; Ford, S.; Green, J. Cultura Transmedia: La Creación de Contenido y Valor en una Cultura en Red; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| List of Credits | |

|---|---|

| Executive Production | Jesús Colmenar and Cristina López Ferraz |

| Co-production | Javier Gómez Santander and Migue Amoedo |

| Directors | Jesús Colmenar, Koldo Serra, Álex Rodrigo and Javier Quintas |

| Writers | Luis Moya, Juan Salvador López, Ana Boyero, Emilio Díez, Esther Morales, Esther Martínez Lobato, Javier Gómez Santander and Álex Pina, coordinated by Javier Gómez Santander |

| Visual concept and directors of photography | Migue Amoedo, David Azcano and Sergi Bartroli |

| Cast | Úrsula Corberó, Álvaro Morte, Itziar Ituño, Pedro Alonso, Alba Flores, Miguel Herrán, Jaime Lorente, Esther Acebo, Enrique Arce, Darko Peric, Hovik Keuchkerian, Luka Perós, Belén Cuesta, Fernando Cayo and Rodrigo de la Serna, among others |

| S3 | S4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total of tweets | 62 | 100 |

| Average tweets per day | 2 | 3 |

| Likes | 18.735 | 111.243 |

| Average likes per tweet | 302 | 1.112 |

| Average likes per day | 625 | 3.708 |

| RT | 1.846 | 14.292 |

| Average RT per tweets | 30 | 143 |

| Average RT per day | 62 | 476 |

| Replies | 652 | 569 |

| Average replies per tweet | 10 | 6 |

| Average replies per day | 21 | 19 |

| S3 | S4 | |

| #LaCasaDePapel | 38 | 76 |

| Retweets | 5 | 27 |

| Multimedia | 3 | 26 |

| Words referring to pandemic | 0 | 13 |

| Compound | Negative | Neutral | Positive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3 | −0.073 | 0.043 | 0.938 | 0.019 |

| S4 | 0.0005 | 0.019 | 0.963 | 0.018 |

| SEASON 3 | SEASON 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Used Words | Repetitions | Used Words | Repetitions |

| Lacasadepapel | 38 | Lacasadepapel | 65 |

| Tokio | 11 | Series | 14 |

| Enjoy | 9 | Professor | 11 |

| Character | 7 | Robbery | 10 |

| Robbery | 7 | Tokio | 8 |

| Professor | 7 | Episode | 8 |

| Series | 6 | Denver | 8 |

| Season | 6 | Plan | 8 |

| Río | 5 | Coronavirus | 7 |

| Úrsula | 4 | Río | 6 |

| Finale | 4 | Úrsula | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cristófol Rodríguez, C.; Meliveo Nogués, P.; Cristòfol, F.J. Release of the Fourth Season of Money Heist: Analysis of Its Social Audience on Twitter during Lockdown in Spain. Information 2020, 11, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11120579

Cristófol Rodríguez C, Meliveo Nogués P, Cristòfol FJ. Release of the Fourth Season of Money Heist: Analysis of Its Social Audience on Twitter during Lockdown in Spain. Information. 2020; 11(12):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11120579

Chicago/Turabian StyleCristófol Rodríguez, Carmen, Paula Meliveo Nogués, and Francisco Javier Cristòfol. 2020. "Release of the Fourth Season of Money Heist: Analysis of Its Social Audience on Twitter during Lockdown in Spain" Information 11, no. 12: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11120579

APA StyleCristófol Rodríguez, C., Meliveo Nogués, P., & Cristòfol, F. J. (2020). Release of the Fourth Season of Money Heist: Analysis of Its Social Audience on Twitter during Lockdown in Spain. Information, 11(12), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11120579