Abstract

With the passing of the last testimonies, Holocaust remembrance and Holocaust education progressively rely on digital technologies to engage people in immersive, simulative, and even counterfactual memories of the Holocaust. This preliminary study investigates how three prominent Holocaust museums use social media to enhance the general public’s knowledge and understanding of historical and remembrance events. A mixed-method approach based on a combination of social media analytics and latent semantic analysis was used to investigate the Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube profiles of Yad Vashem, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the Auschwitz–Birkenau Memorial and Museum. This social media analysis adopted a combination of metrics and was focused on how these social media profiles engage the public at both the page-content and relational levels, while their communication strategies were analysed in terms of generated content, interactivity, and popularity. Latent semantic analysis was used to analyse the most frequently used hashtags and words to investigate what topics and phrases appear most often in the content posted by the three museums. Overall, the results show that the three organisations are more active on Twitter than on Facebook and Instagram, with the Auschwitz–Birkenau Museum and Memorial occupying a prominent position in Twitter discourse while Yad Vashem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum had stronger presences on YouTube. Although the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibits some interactivity with its Facebook fan community, there is a general tendency to use social media as a one-way broadcast mode of communication. Finally, the analysis of terms and hashtags revealed the centrality of “Auschwitz” as a broad topic of Holocaust discourse, overshadowing other topics, especially those related to recent events.

1. Introduction

With the advent of increasingly sophisticated communication technologies and with progressive temporal departure from the historical circumstances that marked the “destruction of European Jewry” [1] about 80 years ago, the employment of digital technology has emerged as a specific topic of research in the field of Holocaust studies. As a number of scholars have highlighted, “the cosmopolitan Holocaust memory of the new millennium is synonymous with digital technology” [2] (p. 331). Efforts to save and preserve historical archives combined with attempts to safeguard the testimonies of the last survivors have resulted in numerous undertakings based on the use of advanced digital technologies. The first prominent initiative came from the USC Shoah Foundation’s Institute for Visual History and Education (formerly Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation), a non-profit organization dedicated to recording interviews with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust and other genocides [3]. Subsequently, progressive diminishment of the witness era [4] has further marked the need to preserve testimonies through digital means. One such initiative, the New Dimensions in Testimony, gathers a collection of survivor testimonies in interactive 3D format in a quest to safeguard the possibility of real-time, question-and-answer virtual dialogue with survivors to learn about and appreciate their life experiences [5,6]. In this vein, the idea of a “virtual Holocaust memory” has advanced, embracing both digital and non-digital memory related to the Holocaust and, at the same time, drawing attention to the pervasive nature of the virtuality of memory itself [7].

Overall, digital culture opens up new opportunities for externalising collective memories and, in this regard, social media settings may be considered the main arenas of mediatized memory that are increasingly globalised and transcultural [8,9,10]. Due to technological transformation and the increasingly mediated nature of communication, digital memory is progressively becoming “unanchored” from localised contexts, making both individual and collective memory timeless and spaceless [11,12].

In this light, Holocaust memorials, remembrance centres, and institutions have had a solid presence on the Internet for a considerable time now, curating websites, mailing lists, and other digital services [13,14]. Museums use and produce diverse media to transmit and communicate memorial content, including standard printed media, multimedia productions, (often hands-on) media stations, interactive software, and web-based material and services. Franken-Wendelstorf, Greisinger, and Gries [15] explained how the “learning location museum” has expanded into digital space. Furthermore, museums, libraries, and related cultural institutions have started using social media for the development of digital social archives [16]. Indeed, social media have become standard means by which Holocaust museums, memorials, and institutions disseminate knowledge and reach out to the public, e.g., for publicising upcoming local events.

Within the specific research subfield of social media memory studies [17], which investigates digital memory of historical events such as those related to the Holocaust [11,18], social media Holocaust studies have become a topic of scholarship in its own right. Some recent projects in this area, such as Eva.Stories on Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/eva.stories/) and the Anne Frank video diary on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/annefrank), have raised considerable controversy. However, the interest in engaging new generations through novel forms of agency in relation to media witnessing and mediated memory is not something that can be dismissed in principle, as they exemplify the co-creation of socially mediated experiences [19]. Although mass culture has increasingly become prominent in the provision of historical knowledge [20], some scholars argue that traditional Holocaust memory environments, such as memorials, cinema, and television, are no longer suitable for contemporary digital users; they see the need to “resurrect” Holocaust commemoration, creating immersive and more engaging memories [2].

For the most part, much critical debate about social media use has focused on so-called dark tourism at Holocaust memorial sites [21], namely visitors taking selfies and other tourist photographs and subsequently sharing them on social media with hashtags [22,23,24]. By contrast, little research has focused on proactive social media use by Holocaust institutions, such as memorials and museums [21,25,26,27]. In today’s digital age, Holocaust museums act both as physical monuments and as mediated and virtual spaces and are thus located at the intersection between commemorative memory and mediated memory [12]. In this sense, they have a multifaceted mandate that covers commemoration, engagement/education of site visitors, enlightenment of the general public’s understanding of the past, as well as strengthening or challenging of historical narratives [28]. Along with archives and libraries, Holocaust museums are public spaces that constitute prime social “memory institutions” and, today, represent the most significant repositories of national and community memories of the Nazi genocide [29].

In this vein, museums position themselves at the intersection of Holocaust memory studies and the emerging field of digital history by making content accessible beyond the physical spaces of museums, research institutions, or archives [25]. However, today, the general expansion of social media into the realm of cultural heritage, not least that of Holocaust remembrance, also raises serious concerns about competing forms of local and national memory, including the narratives conveyed through museums [30]. Despite controversial cases of “multidirectional memory” [31], museums serve to reassure patrons thanks to the legitimacy and authority that people tend to accord to these cultural institutions, especially when set against the confusion of Internet sites promoting antisemitism and treating Holocaust denial as historical truth [29,32].

More recently, the restrictions posed by the COVID-19 pandemic on cultural institutions and heritage sites have accelerated the proliferation of digital memory [33]; a growing use of social media has been a natural response to the limitations posed specifically on in situ socialisation, thereby giving impetus to a shift from complex onsite digital technology to online social media. Various campaigns, such as #RememberingFromHome and #ShoahNames, were launched by Yad Vashem [34] to celebrate Israeli Holocaust Remembrance Day and to foster engagement, participation, and users’ active response through sharing, posting, and commenting, thus configuring new memory ecologies [35].

This study analyses how three Holocaust museums—Yad Vashem, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the Auschwitz–Birkenau Memorial and Museum—use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube to engage their communities both at the content-page and at relational levels. The aim is to investigate what communication strategies the three museums adopt regarding generated content, interactivity, and popularity; these are examined in terms of typology of published content as well as engaging terms and hashtags.

2. Related Literature

Among cultural heritage institutions, museums, monuments, and memorials are leading adopters of digital technologies for education and dissemination activities. These institutions are early up-takers of the Internet, driven in part by the widespread push to digitise their archives, thereby making them accessible to an increasingly wide audience. Similarly, they have turned to social media use from the early stages [25,36]. Several studies have focused on how social media has challenged the traditional flow of museum-based information and have blurred the lines traditionally dividing the roles of exhibition developers, designers, and educators [37]. Other studies have investigated the tensions and synergies between traditional and modern museum practice from the perspective of ethical issues connected to transparency, censorship, and respect for constituencies, especially with the museum relinquishing direct control over their media content [38]. At the same time, paramount importance has been stressed in encouraging different levels of public participation, ranging from merely enjoying content to exercising more participatory roles through the co-creation of new content. This participative turn in cultural policy relies on the paradigm of cultural democracy, according to which diverse social groups should obtain acknowledgement of their cultural practices and no assumption should be made of any superior imperative in the transmission of cultural expression [39].

In this light, the different degrees of engagement with cultural heritage institutions—attendance, interaction, and co-construction—are also reflected in their social media presence. The participatory culture imbued in social media [40] is also reflected in the ways that museums act as intermediaries of historical knowledge and cultural heritage through the exploitation of social media as sociotechnical systems and through leveraging their affordances [41]. The focus of recent studies has shifted from engagement to the extent to which social media contribute to the co-construction of dialogue between museums and their visitors [42]. The idea of museums as cultural intermediaries is connected with the concept of online value creation. This is manifest in at least three organizational forms in which museums may engage: (1) marketing, which promotes the face of the institution; (2) inclusivity, which nurtures a real online community; and (3) collaboration, which goes beyond communication and promotes constructive interaction with the audience [43,44].

One of the approaches taken for measuring museums’ social media presence involves gauging social media effectiveness by considering both content and relational communication strategies [45]. According to this approach, engagement is manifested in different behaviours and communication effectiveness ought to be considered in terms of three consumer engagement dimensions: popularity (e.g., the number of followers and likes); generated content (e.g., the number of posts and comments); and virality (e.g., the number of reposts/shares) [30]. Other studies have investigated post writing as a tool for ascertaining museum engagement and have explored engagement with posts and its distribution by focusing on images, hashtags, and mentions [46]. Other techniques based on topic modelling have been used to derive discourse topics in the content of museums’ posts and the interactions these generated [47].

Notwithstanding the above-reported methodological approaches, to the best of our knowledge, no research study has yet investigated social media engagement centring on major Holocaust museums and memorials. Moreover, recent studies have shown that research in the two subfields of Holocaust remembrance and Holocaust education are largely underpinned by different conceptual frameworks. While the former has become a well-established research field, there is a clear lack of empirical research on social media use for teaching and learning about the Holocaust [48]. This study provides a preliminary analysis of what type of content these three major Holocaust institutions publish on social media and how they engage their respective online communities.

3. Rationale of the Study

Holocaust museums’ current pursuit of a dual mission—as sources of cultural heritage and as institutions with an educational calling—is a phenomenon that is increasingly related to their employment of digital technologies [13]. Social media use has the potential to reach millions of people and the power to transform engrained memory paradigms about the historical contexts of national socialism and the Holocaust [49]. Although Holocaust distortion and trivialisation [50] have become increasingly pervasive on Internet sites and social media, at the same time, social media may strengthen Holocaust knowledge and raise awareness of the many forms of Holocaust distortion being propagated, in part thanks to ready (online) access to accurate historical scientific knowledge on which to judge historical facts [51].

In this sense, there is a need to raise awareness about the potential that social media channels offer to museums and memorials for Holocaust education so that they can better engage their audiences; this involves not only promoting cultural activities and initiatives but also adopting effective social media practices for disseminating accurate historical information.

This study aims to provide a preliminary analysis of social media engagement in three major Holocaust museums: Yad Vashem (YV) in Israel, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), and the Auschwitz–Birkenau Memorial and Museum (AMM) in Poland. The reasons for focusing on these museums lie in their representativeness of worldwide Holocaust heritage, their prominence in terms of the number of visitors they receive annually, and their importance as agencies in the field of Holocaust education. Moreover, despite variance in their Holocaust narratives and their differing social, cultural, and political agendas [52], they are all prominent Holocaust heritage tourist sites that play a special role in shaping the collective memory of the Holocaust [8,9,10].

Although many academic studies have investigated these museums singularly or as part of a group of major heritage sites (e.g., [53,54,55,56]), very few have researched their use of social media [2,21,23,24,25,57]. All three museums run active social media profiles on several platforms in order to share news about their special events and educational initiatives as well as to publicise important dates and ceremonies. In this endeavour, they have adopted their own hashtags—#yadvashem, #USHMM, and #Auschwitz—to make it easy for people to locate their official communication. Despite the advent of this stream of activity, research has yet to produce a comprehensive overview of how these three museums use Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube as part of media-related learning and socially inherited memory.

Accordingly, this study aims to provide an answer to the following specific research questions:

- What kind of content do the three museums publish via their social media profiles?

- What kind of interaction takes place with these profiles?

- What types of content engage the fans/followers most?

4. Methods and Procedure

This study adopts a mixed-method approach grounded on established methods for social media research [58] and is based on social media analytics and latent semantic analysis. Social media analytics are considered a powerful means not only for informing but also for transforming “existing practices in politics, marketing, investing, product development, entertainment, and news media” [59]. In cultural heritage studies on museums’ use of social media, social media analytics have been used to evaluate the impact of museums’ events [60,61] and to extract inspiring pronouncements [62].

Social media analytics were employed to investigate the three institutions’ use of four different social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Specifically, Instagram was included in this group because it “encourages conversation and empathy, keeping the Holocaust visible in youth discourses” [22] (p. 160) and because it offers a different perspective on Holocaust museums’ engagement with social media. Table 1 reports the list of profiles for the three museums investigated here.

Table 1.

List of social media profiles per museum (the date of profile creation/activation is shown in brackets).

The activity around these social media profiles was analysed in terms of (1) content (e.g., post frequency and format, and type of information), (2) interactivity (e.g., user response and engagement), and (3) popularity (e.g., number of fans/followers, shares, etc.). This approach is derived from an analysis framework that distinguishes between content and relational communication strategies and that measures the effectiveness of fan pages and posts [45].

Unlike previous studies [63] that relied on the analytics provided by the Museum Analytics website (http://www.museum-analytics.org), this study uses Fanpage Karma (https://www.fanpagekarma.com/) as its reference social media data analysis platform to retrieve data from Facebook pages, Twitter profiles, Instagram profiles, and YouTube channels. Fanpage Karma is one of the leading providers of social media analytics and monitoring. It provides valuable insights into posting metrics, strategies, and the performance of profiles on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Pinterest. The service allows for the creation of dashboards and benchmarks for social media profiles as well as provides instant reports (Excel, PowerPoint, and PDF) and email updates. The trial version provides metrics for the last 28 days for public pages, while the paid service allows personalised timeframe setting. Table 2 shows a sample of metrics considered for the analysis. Data analysis covers two months of activity from 6th July to 7th September 2020.

Table 2.

List of metrics per platform.

In addition to social media analytics metrics, this study also considered latent semantic analysis (LSA) [64]. This is a technique adopted in natural language processing, in particular distributional semantics, that analyses relationships between words; in this study, it was employed to determine the topical structure of communication. LSA was applied to words and hashtags to analyse what words or strings of words are most frequently used in posts/tweets. Given the functional importance and pervasive use of hashtags in Twitter, these have been the subject of numerous studies that highlight their status as polysemic texts embodying multiple meanings and usages [65,66]. In this study, the aim is to provide an overview of the topics and phrases that appear most often and to discover which hashtags engage the fans/followers most.

5. Results

An initial analysis was conducted by inspecting social media analytics, which provided insights about how the three museums—Yad Vashem (YV), the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), and the Auschwitz–Birkenau Memorial and Museum (AMM)—used Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube in the two-month period from 6th July to 7th September 2020. Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 report the analytics related to the content, interactivity, and popularity of these three museums on the four social media platforms.

Table 3.

Content, interactivity, and popularity of museums’ Twitter profiles.

Table 4.

Content, interactivity, and popularity of museums’ Facebook pages.

Table 5.

Content, interactivity, and popularity of museums’ Instagram profiles.

Table 6.

Content, interactivity, and popularity of museums’ YouTube channels.

5.1. Content

If we look at content categories, we see that the highest number of posted content was found on Twitter (Table 3), where out of 3476 tweets, 90.2% (N = 3136) was produced by AMM, with an average of 49 tweets published per day. In terms of content types, in general, more than half of the tweets contained images and/or links. While USHMM tended to publish more original content than the other two profiles (N = 142; 96.6%), AMM republished the most content produced by other Twitter profiles (N = 2140; 68.2%).

If we look at Facebook posts (Table 4), the situation is very varied as far as the different types of content are concerned. The content published on Facebook is, on the other hand, more often published by USHMM: out of 246 posts, USHMM accounts for more than half of the content published (N = 141; 57.3%), with an average of 2.2 posts per day. While external links are prominently a feature in USHMM content, (N = 105; 74.5%), AMM and YV (to a lesser degree) make massive use of images (N = 66; 90.4%, and N = 22; 68.8%, respectively). Video content is employed more frequently by YV (N = 7; 21.9%) and USHMM (N = 22; 15.6%), although to a lesser extent than images.

As far as Instagram use is concerned (Table 5), content distribution is more homogeneous (USHMM: N = 66, 36.3%; AMM: N = 63, 34.6%; and YV: N = 53, 29.1%). Picture-posts account for most of the content, while YV also tends to publish a small amount of carousel-posts (N = 7; 13.2%). The USHMM profile also includes a small percentage of video-posts (N = 4; 6.1%).

Finally, YouTube activity (Table 5) was higher for YV (N = 11; 50%) and USHMM (N = 9; 40.9%) than for AMM (N = 2; 9.1%), although the frequency of video posting per day was quite low (N = 0.11). All three channels published original content.

5.2. Interactivity

Interactivity was largely investigated using analytics (e.g., the number of total comments/likes or post/tweet interaction) and engagement. For Twitter (Table 3), along with a high level of variance between the number of total likes that each profile’s content attracted, we also found that AMM tweets tend to receive more likes than those of the other two profiles (N = 1296 versus 220 for USHMM and 103 for YV). However, if we look at Twitter interaction—the average number of interactions per day on a given day’s tweets in relation to the total number of followers accrued on that same day in the selected period—we can see that both YV and AMM report a similar percentage (0.17% and 0.15%, respectively). Engagement levels—the average number of interactions per day on tweets on a given day in relation to the number of followers accrued on that same day in the selected period—were found to differ significantly between the three profiles: AMM had the highest engagement among the three profiles, with 7.4% versus 0.2% for USHMM and 0.5% for YV. Finally, for the Twitter-specific metric conversations (a measure determined by the ratio of @-reply tweets to all tweets published in the selected period interacting with other Twitter profiles), YV had a higher ratio (48%) than USHMM (25%) or AMM (13%).

Turning to interactivity on Facebook (Table 4), this was gauged not only by the number of comments on posts, post interaction, and engagement but also by metrics such as the number of posts by fans, fan posts that received comments by the profile page, fan posts that received reactions from the profile page, and comments on user posts from other fans. Regarding the ratio of comments per post and the ratio of reactions per post, USHMM attracted higher activity on both counts: 64,238/141 = 455.6 and 587,231/141 = 4164.7 respectively. For post interaction—the average number of interactions per post; reactions such as Like, Love, Hahah, Thankful, Wow, Sad, and Angry; comments; and shares on posts made on a given day in relation to the number of fans accrued on the same day in the selected period—AMM attracted the most activity (1.1%). This is in line with the engagement metrics—the average number of interactions per day on posts made on a given day in relation to the number of fans accrued on the same day in the selected period—with AMM accounting for 1.3% and USHMM accounting for 1.1%. However, the situation is different when we look at the level of users’ active posting and the number of comments or reactions they receive. Here, there is a huge difference among the three profiles: while users post new content almost exclusively in USHMM (N = 141) and to a minor extent in the AMM page (N = 13), none of the users’ posts received comments by the page owner and only a limited number of posts from USHMM page users’ posts received reactions from the page itself (N = 8) or comments from other fans (N = 5).

Posts on Instagram were inspected in terms of the number of comments and likes, post interaction, and engagement (Table 5). The ratio of comments per post is higher in USHMM (6340/66 = 96.1) and AMM (5966/63 = 94.7), while the ratio of likes per post is prevalent in AMM (218,939/63 = 3475). Post interaction metrics—the average number of organic likes and comments per post on posts made on a given day in relation to the number of followers accrued on the same day in the selected period—are similar in all three profiles, ranging from YV’s 3.1% to AMM’s 3.4%. In terms of engagement—the average number of organic likes and comments per day on posts made on a given day in relation to the number of followers accrued on the same day in the selected period—was higher in USHMM and AMM, corresponding to 3.3%.

Finally, YouTube interactivity was assessed mostly through views, likes and dislikes, and comments. YV and USHMM collected higher numbers of views both globally and per video (N = 5908 and N = 4728, respectively) against only 933 for AMM. The likes vs. dislikes ratios are 86% for YV, 88% for USHMM, and 100% for AMM. The number of comments was zero in the case of USHMM and AMM, while YV collected only a very limited number of comments (N = 11).

5.3. Popularity

Popularity was measured in terms of the number of fans/followers and number of retweets or shares. In the case of Twitter (Table 3), AMM has the highest number of followers (N = 1,066,133), followed by USHMM (N = 322,781). This proportion is also reflected in the average number of retweets per tweet, with 297.6 retweets per tweet for AMM, 87.4 for USHMM, and 34.5 for YV.

Facebook popularity (Table 4) is found to be higher in USHMM, with 1,148,716 fans and the highest number of shares (N = 132,892).

Instagram popularity (Table 5) was found to be quite similar among the three profiles, with 108,254 fans for AMM, 104,893 for USHMM, and 75,231 for YV. Follower growth, that is the difference between the number of followers on the first and last days of the selected period, was found to be higher for AMM and USHMM, with 6049 and 5895 additional fans, respectively.

Finally, YouTube popularity was measured via the number of subscribers and subscriber growth. The most popular YouTube channel amongst these three museums is Yad Vashem with 60,300 subscribers, followed by USHMM with 29,900 followers. Although it is the least popular channel with 2700 subscribers, the AMM channel grew by 3.8% during the considered period.

5.4. Topic Content and Hashtag Analysis

A second, latent semantic analysis was conducted by inspecting the most commonly occurring words and hashtags used to identify conversation topics on the four social media platforms.

On Twitter, the most frequently used words by the three profiles are “educate” (N = 1.6k), “history” (N = 1.6k), “people” (N = 1.2k), “learn” (N = 1.1k), “online” (N = 1.1k), and “visit” (N = 1.1k). However, if we look at the profiles individually, we can see that these words largely coincide with those most used by the AMM profile, while “Nazi” (N = 76), “Holocaust” (N = 49), and “Jews” (N = 35) tend to prevail for USHMM and “Jews” (N = 46) and “Holocaust” (N = 43) tend to prevail for YV.

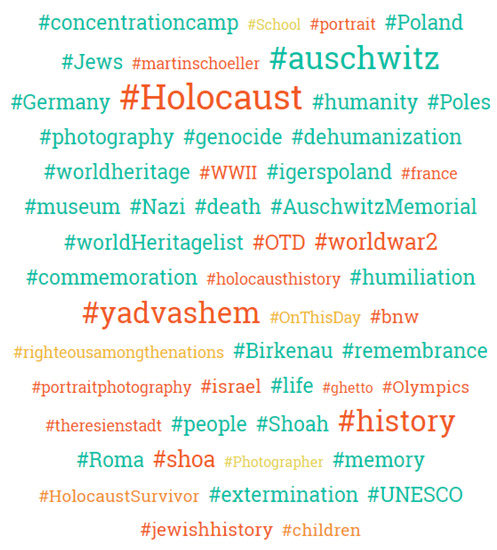

For Twitter hashtags, Figure 1 presents those most frequently used by the three Twitter profiles. We can see that #Auschwitz is clearly the most frequently used (N = 2.6k), although it does not attract a high level of engagement. Indeed, despite having a lower number of occurrences, hashtags such as #theresienstadt (N = 105) and #zigeunerlager (N = 61) generate higher engagement. Breaking down these figures by profile, we see that the use of #Auschwitz is found only on the AMM profile, while USHMM mostly used hashtags such as #otd [on this day] (N = 17) and #antisemitism (N = 8), while more frequently adopted hashtags on YV were #otd [n this day] (N = 59), #martinschoeller, (N = 19) and #75survivors (N = 18).

Figure 1.

Hashtags that the museums used most frequently on Twitter (relative frequency is expressed both by text size and by colour).

For Facebook, the most popular words employed in posts were “camp” (N = 163), “Nazi” (N = 130), “Jews” (N = 114), and “Holocaust” (N = 109). In terms of differences among the three profiles, AMM’s most frequent words were “camp” (N = 102), “prisoner” (N = 68), and “Auschwitz” (N = 50), while USHMM’s were “Nazi” (N = 101), “Holocaust” (N = 63), and “Jews” (N = 61) and YV’s were “Holocaust” (N = 37), “family” (N = 26), and “Jews” (N = 26).

Looking at the use of hashtags on Facebook (Figure 2), the most frequent were #Auschwitz (N = 45) and #backtoschool (N = 4), while the one attracting most engagement was #antisemitism (N = 5). Broken down by institution, #Auschwitz was the most frequent and engaging hashtag for AMM, while #antisemitism was the most popular and engaging (N = 5) for USHMM and #backtoschool (N = 3) was that for YV.

Figure 2.

Hashtags that the museums used most frequently on Facebook (relative frequency is expressed both by text size and by colour).

As for Instagram content analysis, the top words employed were “camp” (N = 120), “Jews” (N = 117), “deported” (N = 95), “Nazi” (N = 94), and “Jewish” (N = 93): with “camp” (N = 49) for AMM, “Nazi” (N = 88) and “Jews” (N = 57) for USHMM, and “Jews” (N = 48) and “camp” (N = 42) for YV being the most employed.

Figure 3 shows that the most commonly used Instagram hashtag was #Holocaust (N = 80) while the most engaging were #Auschwitz (N = 67), #history (N = 54), and #yadvashem (N = 53). Broken down, the most popular were #Auschwitz (N = 56) for AMM; #Holocaust (N = 28) and #history (N = 8) for USHMM; and #yadvashem (N = 53), #Holocaust (N = 41), and #history (N = 35) for YV.

Figure 3.

Hashtags that the museums used most frequently on Instagram (relative frequency is expressed both by text size and by colour).

Given the lack of hashtags use on YouTube, the analysis focused exclusively on word frequency. The results show that the posted videos cover a range of topics, with a prevalence of words such as “Holocaust” and “Auschwitz–Birkenau” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Words that the museums used most frequently words on YouTube (relative frequency is expressed both by text size and by colour).

6. Discussion

This study investigated how a sample of prominent Holocaust museums and organisations use social media to engage their audience about topics related to the Holocaust. The results of this preliminary investigation show that, in general, the three Holocaust organisations are quite active on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, although with differing capacities to attract followers and to engage with them. Overall, the three profiles are more active on Twitter than on the other two social media, and publication date does not seem to influence the capacity to attract followers or to frequently produce content. At the same time, notable differences emerged. While AMM’s activity is well established, especially on Twitter, with the highest number of followers and tweets published daily, USHMM is more (globally and daily) active and popular on Facebook; conversely, YV seems to invest more into YouTube videos. The particular popularity of AMM’s Twitter profile is highlighted by the high average number of retweets per tweet. USHMM’s Facebook page has the highest number of shared posts; they have had a presence on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube for more than 10 years now, and this testifies to their social media commitment. This prioritisation is also reflected in the declaration of the Auschwitz–Birkenau Memorial and Museum to invest in “a place for discussion which is not available on the official website” [67] and to engage with Holocaust mockers and deniers [68]. In a similar vein, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has recently released a document in which they advocate the role of social media in countering Holocaust denial and providing accurate knowledge for history lessons [69]. Instagram adoption is a more recent phenomenon, and here, no significant differences emerge between the three museums except for the more pronounced growth rate for USHMM and AMM. With respect to YouTube activity, Yad Vashem has a long tradition of video production, which is also reflected in the number of subscribers/fans and interactions related to their channel.

Regarding the first research question (content type), the data show that the three museums tend to publish new or original contents on their social media profiles except for AMM’s Twitter profile, where there is a prevalence of reposted (retweeted) contents produced by third parties. This demonstrates that the Polish museum’s Twitter profile acts as a “bridge” among other Holocaust organisations’ profiles, thus contributing to cross-referencing and network-building among Holocaust commemoration bodies. Further research might investigate how social media is used for community building among Holocaust organisations, with opportunities for the development of cooperation strategies and experiences [27]. As for content media typology, AMM and YV have a stronger tendency to publish Twitter content that contains images and/or links to external resources, while USHMM seems to prefer textual information. This trend is also reflected to some extent on Facebook, where USHMM tends to publish textual content accompanied by links to external resources while YV and AMM make extensive use of images and YV of video content. In this regard, future research might also investigate the relationship between the use of images and visual content and user engagement, following the example set by some recent forward-looking research studies [46]. Finally, as far as Instagram is concerned, the only institution to make (limited) use of video in addition to the more standard picture or carousel posts is USHMM. However, further research is needed to study Instagram’s aesthetic visual communication and how Instagram grammar [70] encourages conversation and empathy, especially in youth discourse [22].

In response to the second research question, interactivity was found to be globally higher on Instagram, where no major difference emerged among the three museums in terms of post interaction and general interactivity, although USHMM and AMM posts seem to attract more comments. More specifically, the situation changes completely when considering Twitter, where AMM has by far the highest engagement level, also borne out of the high number of likes per tweet that it attracts. However, if we look at the average number of tweet responses to tweets on a given day in relation to the number of followers (Twitter interaction), there is no significant difference between YV and AMM, showing that more content published does not necessarily mean more user interaction. On YouTube, we found a significant level of passive participation, with a high number of views and likes but no active responses in terms of comments left. However, the most interesting outcomes from the data analysis are in regards to Facebook. The multifaceted metrics available on Facebook activity such as the number of fan posts and interaction with these posts allows for a deeper analysis of how content co-construction unfolds on this social media platform. While USHMM’s Facebook page allows users to post their own photos or other content, the other two profiles do not allow active participation in their page content. Despite this, USHMM has a very low reaction rate to visitors’ posts and, more generally, there is a lack of interaction among the page users themselves. This points to a broadcast-mode use of social media, which is broadly in line with previous studies showing a tendency towards mono-directional communication [26,47]. This trend has been emphasised in other studies, which have highlighted the passivity of “Holocaust institutions whose staff members prefer one-directional communication, ‘broadcasting’ a carefully shaped, widely acceptable message via social media but refusing to engage further and bring their considerable expertise to bear on the difficult moral questions of how to develop an appropriate communicative memory of war crimes and what political consequences to draw from that memory” [2] (pp. 323–324). However, as stressed in other studies [24], the way in which AMM, for instance, engages with Instagram followers shows that it can be possible to exert less control over new channels of communication and representation, thus allowing Holocaust-focused institutions to assume an increasingly visible role in transnational social media Holocaust discourse. Nevertheless, further study and more rigorous methodological approaches are required to understand how Holocaust institutions are placing users (and their responsibility for the content they choose to post on social media) at the centre of the debate on sociohistorical agency in the digital age. In the case of this preliminary study, no specific evidence emerges that there has been an erosion of institutional power over how Holocaust organisations and Holocaust memory are presented and curated [24] or how social media users are exercising agency in the co-construction of Holocaust digital memories [42]. Further research is needed to support these claims as well as to investigate how the perceived threat and actual manifestation of antisemitic and hate speech may be factors potentially conditioning the way memorials approach and embrace social media [26].

Finally, the third research question regards the type of content that mostly strongly engages fans/followers. This entailed latent semantic analysis of the most frequently used hashtags and words. The analysis has revealed a set of terms and hashtags that refer to the basic lexicon of Holocaust history, which attests to users’ strong interest in historical knowledge and less emphasis on the recent past or on analogies between contemporary events and WWII history. In this light, as Kansteiner [2] (p. 324) has highlighted, Holocaust-themed social media pages seem mostly to represent “a cyberspace address where [the subscribers] can hang out with peers, pursue their genocide memory interests by adding a thoughtful facet to their virtual selves, and then return to their comfortable lives”. Another matter of concern relates to the centrality of Auschwitz, both as a hashtag used by Holocaust organisations and as a broad topic of Holocaust discourse. This is reflected in the dominant popular perception of the Holocaust in which Auschwitz and related imagery represents an icon of the spatiality of the Jewish genocide [71,72,73]. Whether the centrality of “Auschwitz” overshadows—and hence inhibits—topical discourses on final solution topics that are less familiar to the wider public is an issue worthy of more in-depth future research, as is whether it poses problems of the overall paucity of Holocaust remembrance, such as the Holocaust by bullets [74].

7. Limitations and Conclusions

While this study has provided some useful insights based on a combination of social media analytics and topic modelling, some limitations need to be recognised. First of all, the study sample generated for this study covered a timespan stretching across the summer of 2020, when museums were still struggling to adjust to the COVID-19 pandemic. Their social media contents and publication strategies may have been influenced by contingent circumstances, as ordinary activity was disrupted. In this respect, further research might investigate, for instance, a possible overlap of content between Facebook and YouTube to increase the provision of visual content due to the closure of museums. A second limitation concerns the adoption of the Fanpage Karma analytic service, which provides metrics and tools for analysis mostly based on a marketing approach. In future studies, other monitoring tools may be used to compare a diverse set of metrics and indications for engagement measures. Thirdly, there is also a need to use mixed-method approaches that combine quantitative tools and qualitative instruments. For example, it is important to analyse posted content through a qualitative codebook that may use predefined or inducted categories to analyse historical content, moral lessons, or contemporary events related to Holocaust topics. More sophisticated tools for (automatic) semantic analysis could complement a qualitative approach as such. Moreover, it will be important to consider diverse meanings of “engagement” applying relative weighting to the metrics adopted for determining engagement and interactivity (in our case, e.g., “YouTube interactivity was assessed mostly through views, likes and dislikes, and comments.”). These are each quite different in the nature and level of visitor engagement with the content. Finally, the content of visitors’ comments, which were not the object of this study, should be considered in future research to investigate how fans/followers interact textually or with multimedia content with institutional pages/profiles. Whatever the specific issues future research focuses on, research based on social media data will allow “unprecedented insights in the generation of historical consciousness because multi-platform consumption of historical content and explicit generation of historical interpretation can be recorded in unprecedented depth and breadth” [2] (p. 330).

Funding

This work was supported by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) under grant no. 2020-792 “Countering Holocaust Distortion on Social Media. Promoting the positive use of Internet Social Technologies for teaching and learning about the Holocaust”.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data were obtained through a paid service and are not freely available.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out as part of the author’s research project “Teaching and learning about the Holocaust with social media: A learning ecologies perspective”—Doctoral programme in “Education and ICT (e-learning)”, Universat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hilberg, R. The Destruction of the European Jewry, revised and definitive edition; Holes and Meir: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kansteiner, W. Transnational Holocaust Memory, Digital Culture and the End of Reception Studies. In The Twentieth Century in European Memory: Transcultural Mediation and Reception; Andersen, T.S., Törnquist-Plewa, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, Belgium, 2017; pp. 305–343. [Google Scholar]

- Shandler, J. Holocaust Memory in the Digital Age: Survivors’ Stories and New Media Practices; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wieviorka, A. The Era of the Witness; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frosh, P. The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, M. The Last Goodbye (2017): Virtualizing Witness Testimonies of the Holocaust. Spectator 2020, 40, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, V.G. What is ‘virtual Holocaust memory’? Mem. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.; Hazan, H. Marking Evil: Holocaust Memory in the Global Age; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kansteiner, W.; Presner, T. Introduction: The Field of Holocaust Studies and the Emergence of Global Holocaust Culture. In Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture; Fogu, C., Kansteiner, W., Presner, T., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.; Sznaider, N. The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, A. Media, memory, metaphor: Remembering and the connective turn. Parallax 2011, 17, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. The unanchored past: Three modes of collective memory. Mem. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Waterhouse-Watson, D. The Future of the Past: Digital Media in Holocaust Museums. Holocaust Stud. 2014, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanzelter, E. At the crossroads with public history: Mediating the Holocaust on the Internet. Holocaust Stud. 2015, 21, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken-Wendelstorf, R.; Greisinger, S.; Gries, C. Das Erweiterte Museum. Medien, Technologien und Internet; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernsen, D.; Kerber, U. Praxishandbuch Historisches Lernen und Medienbildung im digitalen Zeitalter; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Birkner, T.; Donk, A. Collective memory and social media: Fostering a new historical consciousness in the digital age? Mem. Stud. 2020, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Hansen, J.; Hoskins, A.; Reading, A. Save As Digital Memories; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henig, L.; Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T. Witnessing Eva Stories: Media witnessing and self-inscription in social media memory. New Media Soc 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, A. Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wight, A.C. Visitor perceptions of European Holocaust Heritage: A social media analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commane, G.; Potton, R. Instagram and Auschwitz: A critical assessment of the impact social media has on Holocaust representation. Holocaust Stud. 2019, 25, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziel, I. “Romantic Auschwitz”: Examples and perceptions of contemporary visitor photography at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Holocaust Stud. 2016, 22, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, M. Selfies from Auschwitz: Rethinking the Relationship between Spaces of Memory and Places of Commemoration in the Digital Age. Digit Icons 2017, 18, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lundrigan, M. #Holocaust #Auschwitz: Performing Holocaust Memory on Social Media. In A Companion to the Holocaust; Gigliotti, S., Earl, H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 639–654. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, S. Holocaust memorialisation and social media. Investigating how memorials of former concentration camps use Facebook and Twitter. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on Social Media—ECSM 2019, Brighton, UK, 13–14 June 2019; pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, M.; Manca, S.; Haake, S. Sozialen Medien als digitale Räume in der Erinnerung an den Holocaust: Eine Vorstudie zur Twitter-Nutzung von Holocaust-Museen und Gedenkstätten. Merz 2020, 6, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, L.K. Hello from the other side: Museum educators’ perspectives on teaching the Holocaust. Teach. Dev. 2018, 22, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, A. Digital interactivity in public memory institutions: The uses of new technologies in Holocaust museums. Media Cult. Soc. 2003, 25, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. Is Eastern European ‘Double Genocide’ Revisionism Reaching Museums? Dapim 2016, 30, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, M. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Topor, L. Dark Hatred: Antisemitism on the Dark Web. J. Contemp. Antisemitism 2019, 2, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaroudi, M.; Echavarria, K.R.; Perry, L. Heritage in lockdown: Digital provision of memory institutions in the UK and US of America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Virtual Name-Reading Campaign to Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day. 2020. Available online: https://www.yadvashem.org/downloads/name-reading-ceremonies.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Transformation of Holocaust Memory in Times of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.iwm.at/always-active/corona-focus/tobias-ebbrecht-hartmann-transformation-of-holocaust-memory-in-times-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Marakos, P. Museums and social media: Modern methods of reaching a wider audience. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2014, 14, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, R. Keep the Conversation Going: How Museums Use Social Media to Engage the Public. Mus. Sch. 2017, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.S. Ethical issues of social media in museums: A case study. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2011, 26, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, L.; Négrier, E. The participative turn in cultural policy: Paradigms, models, contexts. Poetics 2018, 66, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Mizuko, I. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, S. ResearchGate and Academia.edu as networked socio-technical systems for scholarly communication: A literature review. Res. Learn. Technol. 2018, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronemann, S.T.; Kristiansen, E.; Drotner, K. Mediated co-construction of museums and audiences on Facebook. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2015, 30, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, J. Enacting engagement online: Framing social media use for the museum. Inf. Technol. People 2011, 24, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Meléndez, A.; del Águila-Obra, A.R. Web and social media usage by museums: Online value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, C.; Garrido, M.-J.; San Jose, R. What Works in Facebook Content Versus Relational Communication: A Study of their Effectiveness in the Context of Museums. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Diaz, M.L.L.; Riva, P. Exploring the Importance of Facebook Post Writing as a Museum Engagement Tool. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Social Media—ECSM 2020, Larnaca, Cyprus, 2–3 July 2020; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, M.L.; Arnaboldi, M. The participative turn in Museum: The online facet. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Social Media & Society (SMSociety’20), Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–24 July 2020; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Manca, S. Bridging cultural studies and learning sciences: An investigation of social media use for Holocaust memory and education in the digital age. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, H. Geschichte im Social Web: Geschichtsnarrative und Erinnerungsdiskurse auf Facebook und Twitter mit dem kulturwissenschaftlichen Medienbegriff Medium des kollektiven Gedächtnisses’ analysieren. In Medien Machen Geschichte: Neue Anforderungen an den Geschichtsdidaktischen Medienbegriff im Digitalen Wandel; Pallaske, C., Ed.; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Y. Creating a “Usable” Past: On Holocaust Denial and Distortion. Isr. J. Foreign Aff. 2020, 14, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, H. Social Media und Holocaust Education. Chancen und Grenzen historisch-politischer Bildung. In Holocaust Education Revisited. Holocaust Education–Historisches Lernen–Menschenrechtsbildun; Ballis, A., Gloe, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rotem, S.S. Constructing Memory: Architectural Narratives of Holocaust Museums; Peter Lang AG: Bern, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum, M.; Kramer, A. The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Donals, M. Figures of Memory: The Rhetoric of Displacement at the United States Holocaust Memorial; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, C. Encountering Auschwitz: Touring the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Holocaust Stud. 2019, 25, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, L.A. Genocide and Relevance: Current Trends in United States Holocaust Museums. Dapim 2016, 30, 282–295. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, H. Erinnerungskulturen im Social Web. Auschwitz und der Europäische Holocaustgedenktag auf Twitter. In Geschichtsunterricht–Geschichtsschulbücher–Geschichtskultur. Aktuelle Geschichtsdidaktische Forschungen des Wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchses. Mit einem Vorwort von Thomas Sandkühler; Danker, U., Ed.; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2017; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, L.; Quan-Haase, A. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lassen, N.B.; la Cour, L.; Vatrapu, R. Predictive Analytics with Social Media Data. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; Sloan, L., Quan-Haase, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 328–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, J.T. #Fashionlibrarianship: A Case Study on the Use of Instagram in a Specialized Museum Library Collection. Art Docum. 2019, 38, 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Villaespesa, E. An Evaluation Framework for Success: Capture and Measure your Social-media Strategy Using the Balanced Scorecard. MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Available online: https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/an-evaluation-framework-for-success-capture-and-measure-your-social-media-strategy-using-the-balanced-scorecard/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Gerrard, D.; Sykora, M.; Jackson, T. Social media analytics in museums: Extracting expressions of inspiration. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, F.; Deltell, L. Social museums: Social media profiles in Twitter and Facebook 2012–2013. Prof. Inf. 2014, 23, 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erz, A.; Marder, B.; Osadchaya, E. Hashtags: Motivational drivers, their use, and differences between influencers and followers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuria, R. Get out of Church! The Case of #EmptyThePews: Twitter Hashtag between Resistance and Community. Information 2020, 11, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Auschwitz Launches Facebook Site. BBC News. 14 October 2009. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8307162.stm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- The Auschwitz Museum Has a Twitter Account, and this Ex-Journalist Runs It. The Times of Israel. 8 January 2017. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-auschwitz-museum-has-a-twitter-account-and-this-ex-journalist-runs-it/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- The Lessons of History and Social Media. US Holocaust Museum. 31 August 2020. Available online: https://us-holocaust-museum.medium.com/the-lessons-of-history-and-social-media-1654446ed848 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Highfield, T.; Leaver, T. Instagrammatics and digital methods: Studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji. Commun. Res. Pract. 2016, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T. Selling the Holocaust: From Auschwitz to Schindler, How History is Bought, Packaged, and Sold; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Partee Allar, K. Holocaust tourism in a post-holocaust Europe: Anne Frank and Auschwitz. In Dark Tourism and Place Identity: Managing and Interpreting Dark Places; White, L., Frew, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.; Karayianni, E. ‘The Holocaust is a place where …’: The position of Auschwitz and the camp system in English secondary school students’ understandings of the Holocaust. Holocaust Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vice, S. ‘Beyond words’: Representing the ‘Holocaust by bullets’. Holocaust Stud. 2019, 25, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Author Biography

Stefania Manca is a Research Director at the Institute of Educational Technology of the National Research Council of Italy. She has a Master’s Degree in Education and is a PhD student in Education and ICT (e-learning). She has been active in the field of educational technology, technology-based learning, distance education and e-learning since 1995. Her research interests include social media and social network sites in formal and informal learning, teacher education, professional development, digital scholarship, and Student Voice-supported participatory practices in schools. She is currently working on a three-year research project about the application of social media to Holocaust education from a learning ecologies perspective. She is author of scientific publications on various topics of educational technology, co-editor of the Italian Journal of Educational Technology (formerly TD Tecnologie Didattiche), and part of the editorial and scientific boards of international and national journals and conferences on technology-enhanced learning.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).