Abstract

Introduction: Nature-based therapy (NBT) has shown positive effects on different health-related outcomes and is becoming a more frequent approach in various rehabilitative interventions. Economic evaluations are widely used to inform decision makers of cost-effective interventions. However, economic evaluations of NBT have not yet been reviewed. The aim of this review was to uncover existing types and characteristics of economic evaluations in the field of nature-based therapeutic interventions. Methods: In this scoping review available knowledge about the topic was mapped. A comprehensive search of selected databases (MEDLINE; EMBASE; CINAHL; Scopus; Cochrane; PSYCinfo; Web of Science) and grey literature was conducted in November 2021. Data was synthesised in a thematic presentation. Results: Three papers met the inclusion criteria, containing differences in design, types and dose of nature-based therapeutic interventions, outcome measures and target groups (n = 648). The papers showed tendencies toward a good treatment effect and positive economic effect in favour of NBT. Conclusions: Three different cohort studies have tried calculating the economic impact of NBT indicating a good effect of the NBT. The evidence on the economic benefits of NBT is still sparse though promising, bearing the limitations of the studies in mind. Economic evaluation of NBT is a new area needing more research, including high-quality research studies where the economic evaluation model is included/incorporated from the beginning of the study design. This will enhance the credibility and usefulness to policy makers and clinicians.

1. Introduction

Natural environments provide humans many and varied benefits, called ecosystem services, ranging from, e.g., provision of food and freshwater, regulating climate and stormwater to pollination, and supporting soil formation [1]. Cultural services are non-material benefits obtained from ecosystem services, and include e.g., nature-based recreation which is important in relation to maintaining mental health [2]. In many indigenous cultures the health beneficial relationships between human and natural environments have deep and well integrated roots that go beyond the pragmatic, material, healing and economic aspects [3]. Over the last decades the number of non-communicable diseases like mental illness, dementia, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stress have had a substantial increase in incidence [4,5,6,7]. Research indicates that nature exposure may reduce mortality [8], increase levels of physical activity [9], affects longevity of the elderly [10], improve mental health [11], and may help people with mental illnesses [12]. Poor mental health entails large costs globally [13], and it has therefore been suggested that visiting natural environments could have an additional economic value through the improved mental health of people getting NBT [14]. Due to the various health benefits of natural environments these are also used in therapeutic interventions.

The interest in and evidence of nature-based therapeutic (NBT) interventions are growing [15]. NBT is here understood as a physical, mental and social rehabilitative intervention fully or partially led by health professionals, in which natural environments and its nature elements are actively and/or symbolically used as therapeutic means [16,17,18] in terms of activities, narrative and storytelling, adapted to a specific target group to promote defined treatment goals [19,20,21,22]. NBT is a complex intervention since it is composed of various interrelated elements that, in isolation or combination, may generate the desired effect of the intervention [23]. The interrelatedness among the components included in NBT are e.g., natural environment type, season, weather, within-group dynamics, therapists and activities. All this makes the NBT a complex intervention both to provide and to measure [24]. NBT has been incorporated into healthcare services as a complementary means of treating physical, mental and cognitive disorders by occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers and psychologists [25,26,27]. NBT differs from conventional therapy by taking place outdoors in and with connection to the natural environment [27,28,29]. The environment may range from wilder nature to therapy gardens specifically designed to support the treatment. Previous literature has shown that NBT has a positive effect on a number of health-related outcomes [30,31,32].

In developing and executing NBT healthcare interventions, outcome-focus has often been towards the effects of reducing symptoms, mortality, hospitalization, medication intake or higher level of self-dependent functionality or quality of life. Health economic exploration of the beneficial effect relative to the costs seems not to have been in focus when designing the intervention studies. As it is, however, this outcome measure is highly relevant to include in order to more fully understand the potential benefits of this kind of intervention [14,15]. Especially since economic evaluations are highly relevant when deciding whether an intervention is to be implemented into society [28,29,30]. Economical evaluation is also a significant contribution to evidence-based practice and in developing clinical guidelines. The methods of health economic evaluations of more traditional therapy-based intervention for mental and physical problems are well established (e.g., stress [31] cardiovascular diseases [32] and depression [33]). At present, it seems that economic evaluations have not yet become integrated in the NBT research [34], and knowledge is sparse on the economic value of NBT both on its own [15] and in comparison to conventional treatment options.

Previous review studies in the field of NBT have identified an insufficient pool of peer-reviewed evidence on economic evaluations [35]. Therefore we found the exploratory nature of a scoping review useful for effectively and rigorously mapping current evidence [36]. Since scoping reviews include papers which do not appear in peer-reviewed journals or bibliographic databases, such papers are typically excluded from more formal systematic reviews because of a lower quality of evidence [36]. This scoping review focuses broadly on nature-based interventions and aims to bring forward an overview of existing economic evaluations of NBT. The purpose is to aid the mapping of the state of affairs and possibly provide suggestions for future research within this field.

2. Methods

The review process was guided by the methodological framework for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) developed by Peters and colleagues, which sets out different stages that govern the development and implementation of scoping reviews [36]. For details of the pre-registered study protocol, see: https://osf.io/f9mq3/ (accessed on 11 September 2021).

The review was conducted by a cross-disciplinary author team of researchers, comprising a health economist (LPK), a public health researcher (CBP), an educational psychologist (SSC), a statistician (PKN), two landscape architects (US, UKS) and two physiotherapists (DVP, HB).

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed through preliminary searches and reading of subject-specific articles, and subsequently refined through synonyms and MeSH/subject headings to cover databases with methodologically diverse publication listings. The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE and then customised for EMBASE, CINAHL, Scopus, Cochrane, PSYCinfo and Web of Science. All terms were searched as keywords and text words in title and abstract, if possible. Additionally bidirectional citation searching was done, where key papers were used to identify additional literature which was subsequently searched for [37]. The seven electronic databases were searched on 19 November 2021. For further details on search terms, see (Appendix A).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria formed the search and identification of relevant sources:

- Study population: Human participants

- Concept/Phenomena of interest: Nature-based therapeutic intervention including an economic evaluation

- Source of evidence: All types of study design; peer-reviewed articles, reports, grey literature

- No restriction towards time limit

- Papers written in English, Danish, Swedish or Norwegian

Opinion pieces, editorials, conference proceedings or similar and publication of abstract only were excluded.

2.3. Selecting Evidence

For the management and screening of abstracts, the search results were uploaded to COVIDENCE (https://www.covidence.org/home, accessed on 11 November 2021) and any duplicate studies were removed. A first screening was conducted independently by two review authors (HB, US), screening titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. If the inclusion of an article was unclear, the reviewers (HB, US) screened the full text; in case of discrepancies, consensus was reached by discussion. In the second independent screening, two reviewers (HB, US) read full-text versions of identified articles to assess their final inclusion; again, consensus was reached by discussion.

2.4. Critical Appraisal

No critical appraisal of the methodological quality of included studies was conducted.

2.5. Extracting Evidence

Data was extracted by three reviewers, using a template adapted from PRISMA-ScR [36], Drummond’s check-list for assessing economic evaluation and Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEER) [38,39], see Table 1. Data was recorded in Excel and entries were cross-checked by the three reviewers (HB, LPK, US) for consistency and accuracy.

Table 1.

Data extraction template.

2.6. Analysis and Presentation of Results

All data was analysed and gathered in a thematic presentation of the results by one of the two joint first authors (HB). This involved close reading and re-reading of the included papers.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Potential Articles

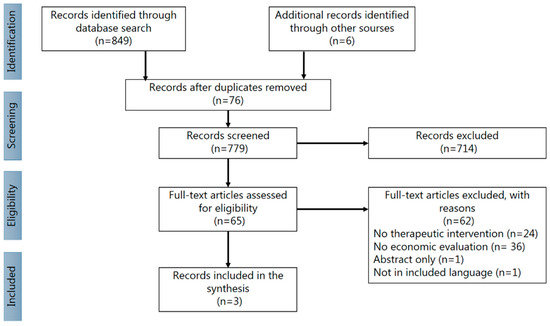

The systematic search in the seven databases revealed 849 potentially relevant titles/abstracts. Additionally six papers were found and added by chain search and search in grey literature [40]. In total, 779 titles/abstracts were screened after removal of duplicates. 714 articles were excluded (498 no economic evaluation, 216 no NBT). Subsequently, 65 full-text articles were screened for eligibility of which 62 were excluded. Accordingly, a total of three papers were included. For further details, see flow chart (see Figure 1) [41].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search procedures and study selection. Source: [41].

3.2. Characteristics of Included Articles

Three papers met the inclusion criteria [42,43,44]. Table 2 summarises key features of the interventions and Table 3 summarises key features of the economic evaluation in the included papers (n = 3).

Table 2.

Total data extraction.

Table 3.

Data extraction of the Economic evaluation.

The three included studies will be presented one by one below.

- Pretty and Barton 2020

Pretty and Barton 2020 [42] is an economic compilation of four different NBTs on four different populations. The British healthcare system has developed an alternative to medical intervention called social prescription, aiming to support people in developing community connections and discover new opportunities to improve health and well-being [45]. All participants in this study had received such a social prescription. The patients in the first described NBT program “Green Light Trust“ were vulnerable youngsters (n = 32) receiving woodland therapy, comprising natural history learning, craft activities, preparing and cooking food, led discussions and walking in woodlands–the whole program of a duration of 10–12 weeks. In the second mentioned study-program, “Ecominds”, adults with mental health challenges (n = 328) underwent NBTs consisting of counselling sessions, cognitive behavioral therapy, or psychotherapy including informal therapy of the NBT program. No further description of the mental health challenges or of the intervention frequencies or period were found. The third study-program, “Trust Links Growing Together”, was for adults with mental health needs and/or learning or other disabilities (n = 154). All participated in therapeutic horticulture as well as a range of peer-support and vocational activities including music, art, creative writing, yoga relaxation, cooking and crafts, 1 to 2 days per week, 50–100 times per year. The last of the four studies, “Living Moment Tai Chi”, is not nature-based and is therefore not included in the data subtraction and analysis. No control groups were included.

The outcome measures were: Life satisfaction/happiness (LS/H) scale (1–10), where 1 indicate poor and 10 indicate great LS/H [46] and reduced loneliness without further description. Time points of assessments, adverse events and serious adverse events were not described. The LS/H-scores in the different programs: “Green Light Trust” program start score: 4.81 ± 2.12 (mean ± standard deviation (SD) to end score 6.17 ± 1.64 (mean ± SD) giving a margin of change of +1.36. The “Ecominds” program had a start score: 6.10 ± 2.33 (mean ± SD), end score: 6.97 ± 2.24 (mean ± SD), margin of change: +0.87, and the “Trust Links Growing Together” program had a start score of 6.22 ± 2.0 (mean ± SD), end score: 7.25 ± 1.93 (mean ± SD), margin of change: +1.03. The change of the life satisfaction/happiness (LS/H) scale (1–10) is comparable to changes that result from significant life events (e.g., new relationship or marriage, +1) [46].

The economic evaluation is an assessment of costs and benefits. Benefits are estimated based on increased life satisfaction/happiness scores and reduction in loneliness. In the “Green Light Trust” program reduced use of public services is included, with a limited description of the assessment, measurement times and follow-up. Intervention costs are reported for two of the three programs and are based on information from the Trust (£960 & £1130 per person per program). A number of economic estimates are reported in the paper. The benefit-cost ratios were calculated for year 1 and year 10 for the “Green Light Trust” program. (Benefit-cost ratio is an indicator of the relationship between the relative costs and benefits of a project) and the ratios were assessed to be 1.71 and 12.9 (for benefits restricted to prevented public health and service costs) and 15.8 and 27.1 (for total benefits). The “Trust Links Growing Together” program had benefit-ratios of 6.42 and 7.61, respectively. However, we failed to find the numbers presented in Table 5 in as in the text, page 13 [42]. The range of net present economic benefits per person from reduced public service use are reported (only in the abstract) to be £830–31,510 after 1 year, and £6450–£11,980 after 10 years. Furthermore, the total economic return to nature-based intervention/mind-body interventions is reported to be £6000–£14,000 per person after year 1, and £8600–£24,500 per person after year 10. The economic returns for prevented costs only (not counting effects on LS/H) are £800–£1500 at year 1, and £5300–£12,300 at year 10.

- 2.

- Elsey et al. 2018

The study by Elsey et al. [43] is a pilot feasibility study where probation service users, >18 years of age are undertaking community orders at either care farms or various comparisons (n = 134) allocated by geographical location of residence to one of the following three

- (I)

- Social enterprise specializing in aquaponics (cultivating aquatic plants and animals), horticulture and skills building (n = 30) or comparison: Charity warehouse sorting secondhand clothes (n = 61).

- (II)

- A religious charity with emphasis on horticulture (n = 2) or the comparison intervention: unspecified projects (n = 2).

- (III)

- A family-run cattle farm focusing on rehabilitation (n = 18) or comparison: Different activity management: addressing alcohol misuse, domestic violence, anger management and driving under influence (n = 21). No data regarding the duration and frequency of the interventions were found.

The primary outcome was the Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE-OM). The CORE-OM includes 34 items, covering four conceptual domains: subjective well-being, problems/symptoms, life/social functioning and risk to self and others. The higher the scores, the more distress is indicated. Secondary outcomes were: CORE-6D (a utility measure) and the Waarwick-Edinberg Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) [47] measuring mental well-being. Further, The Connectedness to Nature Scale [48] and The Nature Relatedness Scale [49], both measuring human connections to nature and environment. In addition, data were collected regarding tailor-made social-care and health-resource use, smoking status, alcohol and drug use, diet and physical activity. Also, probation service data and police records were included. All outcomes were recorded at start of the community order and after 6 months. The pooled CORE-OM results for the care farms were: Start mean: 7.4 95%CI (3.5, 15.15) end mean: 6.8 95%CI (3.5, 12.6), mean change score: -0.6 and for the comparison group at start: mean 7.1 95%CI (3.8, 12.1), end mean 9.25 95%CI (3.8, 15.3), mean change score: +2.15.

The study is a pilot feasibility study that may be considered as a cost-outcome description rather than an actual economic evaluation. Intervention costs are restricted to the costs related to supervision of probation service users and travel costs. Furthermore, the estimated cost related to self-reported public health and service use within the last months was only for a subset of the study population. CORE-OM was transformed to CORE-6D and differences were calculated concerning CORE-6D utility values between the intervention groups and the control group. Estimated average costs of resource use within the past month were £95.74 for the comparison group and £67.23 for the care farms group. The total health and social services resource use costs were significantly higher for comparison users compared to care farm users. Total medication costs were marginally higher for care farm users, however not significant. Including intervention costs, the mean total cost over the last month was marginally higher, but not significant, for comparison users compared to care farm users. No significant difference was found in the mean CORE-6D index score at baseline and 6-month follow-up between the care farm group (mean 0.835 (SD 0.118)) and the control group 0.849 (SD 0.122). The study did not relate costs to effect.

- 3.

- CJC Consulting 2016

The paper by CJC Consulting [44] is a non-peer-reviewed commissioned final report to the Forestry Commission, Scotland, from the Branching Out Program. Here 305 adults with severe and enduring mental health problems, without further description, were allocated to three hours of woodland activity per week over 12 weeks. The woodland activities consisted of health walks and talks, tai chi, conservation activities, rhododendron clearance, bird box construction, bush craft, fire lighting and shelter building. There was no control intervention.

The primary outcome of the intervention was the SF-12 HRQoL questionnaire [50], assessing the impact of health (e.g., physical activities, social activities, bodily pain, mental health) on an individual’s everyday life. The 0–5 score (0 = no problem, 5 = great problem/not possible) indicates whether the participants had self-reported problems or not. These scores were collected pre-program, immediate post-program, and three months post-program. For the economic evaluation, the SF-6 was derived from the SF-12 and used in calculation of Quality of Life Years (QALY).

The economic evaluation can be categorized as a partial cost-utility analysis. The analysis compares costs relative to changes in outcome (QALY) pre- and post-program, but does not include a comparison with another alternative. The study revealed a mean QALY gain of 0.05 for the period 2011–2012, 0.0035 for the period 2014–2015 and 0.0227 for the entire period (2011–2015). The cost per person attending at least one session was £426 (2011/12) and £392 (2014/15). The cost per QALY (2011/12–based on costs £426) was £8600. When using the estimated QALY based on the entire period (2011–2015) cost per QALY was £17,276 (based on costs £392).

3.3. Summary

The above described studies provide different estimates for the economic value effect of NBT interventions. Further they entail different types of participants, use different designs, outcome measures, interventions, dosage and economic evaluations. This makes a common interpretation of the results difficult, though they all show tendencies toward a good treatment effect and positive economic effect, in favour of NBT.

4. Discussion

It has been suggested that natural environments could have an additional economic value through the improved mental health of people visiting them [14]. Nature-based therapy could likewise be characterized as a non-material benefit obtained from ecosystem services, and it is desirable to investigate the economic benefits of the improved health of patients. This scoping review mapped the available economic evaluations of NBT through a thorough systematic search in peer-reviewed databases and grey literature. Not many studies were found in this field. The three included studies have done a worthy effort to explore the field and must be credited for the pioneering effort since no previous studies were available to lean on or to build further upon.

A central finding is that the included studies tried to estimate the economic effect of the NBT although they had methodological limitations and incomplete availability of economical methodological details. Such insufficiency makes it difficult to determine the actual economic effect of the NBT. However, the findings add some insight to the scope of quantifying the benefits of NBT either from a clinical or cost-effectiveness/cost-beneficial standpoint. All the while highlighting that the amount of studies within this field is sparse and makes it visible that there is a need for comprehensive research and a clear elaboration of the constituents and understanding of the investigated NBT intervention.

4.1. Methodological Evaluation

The included studies are first-movers and have just started the elaboration of economic evaluation of NBT. However, they have some substantial limitations and potential bias, which should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

The congruity between study aims and methods, including data collection and interpretation, was generally low. The research was deemed ethical, but no information about ethical approval was available. Othermissing elements were methodological considerations regarding sample size calculation, in- and exclusion criteria for the included participants, blinded assessment, dropouts and intention to treat analyses. In addition, the conclusions were drawn from parts of the collected data without inclusions for the included data set a priori.

There was a lack of details/entirely missing information on, e.g., recruitment procedures [42,44], assessment time and outcome clarification [42]. Likewise no information about in- or exclusion criteria for the participants, heterogeneity between control/comparison group [42,44] or whether the comparison group was given another intervention, not knowing if it was similar to the NBT according to frequency and intensity [43]. In the case of no control group, it is not possible to assess whether the outcome change is because of the intervention, time or other factors in the participants’ lives.

4.2. Economic Evaluations in the Included Studies

It is possible that the economic evaluations in the three included studies are performed after the actual interventions, which would explain the lack of methodic economic evaluation measures included in the study design.

All three studies present considerable methodological inadequacies and do not quite follow the standard way of conducting health economic evaluations [38], but the included papers did explore various elements of economic evaluations of NBT. Pretty and Barton, 2020 calculate benefit-cost ratios, but we find it questionable to categorize the evaluations as cost-benefit analyses. None of the standard methods (e.g., Willingness to Pay and Human Capital Approach) of assessing benefits are used and public health care and service use is only included in one of the three evaluations. The approach used to estimate benefits is sparsely described and the way it is written may lead to the misunderstanding that some of the savings have been counted twice (related to loneliness and GP (family doctor) visits). Intervention costs are only available for two of the three programs and the lacking description of how they are calculated makes it difficult to assess if all relevant costs have been included. In general, the limited descriptions of the programs and the applied approach to estimate the economic measures make it difficult to assess whether all relevant costs and benefits have been included in the analyses. Several economic measures are reported by Pretty & Barton, but it is very difficult to overview what the different numbers are representing and how they relate to each other. For instance, some numbers for net present economic benefit are reported in the abstract, but not found anywhere in the main text. Finally, we are critical of the choice to report the results for those who responded only. The program is offered to all patients, regardless of whether they respond to the intervention or not, and conducting the calculation based on patients with a positive response to treatment overestimate the economic benefit of the program.

The paper by Elsey et al. 2018 is not an actual economic evaluation rather than a feasibility study with the objective to investigate the feasibility of doing a cost-effectiveness study of care farms. The feasibility study is not expected to follow the standards of Drummond’s checklist [38] and CHEER [39]; however, the description of the different elements in the study is limited, which makes it difficult for the reader to assess the applied approach. The description of the calculation of the intervention costs is insufficient, and it is unclear how the different numbers reported in the paper relate to each other.

The report by CJC Consulting 2016 is the study that comes closest to an actual health economic evaluation. However, this study also suffers from several methodological issues. The most significant point of criticism relates to the lack of a control group when calculating changes in QALY. Without a control group we cannot exclude that a similar change in QALY could occur without the patients receiving NBT. Another essential issue is that only costs related directly to the intervention are included in the evaluation. Other relevant costs such as health care utilization are not included in the assessment of the costs. Finally, nothing is mentioned about the perspective of the evaluation or considerations about discounting QALYs and costs.

In general, the three studies indicate that NBT interventions are associated with potential cost savings and increases in quality of life/life satisfaction, with the exception of the Elsey et al. study [43] which found no significant difference in utility scores between the intervention and control group. The results should, however, be assessed with much caution as the studies are associated with considerable methodological inadequacies (as described above). The findings may support that there are indications that NBT is cost effective but there is a lack of solid basis for finally being able to conclude this.

4.3. Nature-Based Therapy

As a result of the growing amount of research, more and more evidence of various benefits of NBT on human health have been generated. Hereto must be mentioned that NBT in this study and in most other studies are performed in the western-world [51]. However, there exist several definitions of terms related to NBT and just as many ways of conducting NBT, as the included studies also show. Further, NBT is a complex intervention with many active components, which can potentially affect the results. This is an inherent complexity in the field when trying to compare and review NBT interventions, which also accounts for this review, where the included studies differ substantially in the content of the interventions. In the absence of several studies that look at nature-based therapeutic interventions and economic evaluation thereof in combination, we have chosen to include the study by Elsey et al., studying care farming only with limited components of NBT, as current review understands and defines it. Further, the studies do no not define their approach or understanding of NBT, nor describe why and how the natural environment and activities are an integral part of the therapy. An elaboration of the therapeutic approach would have been beneficial when comparing the studies.

Within the public health sector there is a growing interest in and demand for transferable guidelines and corporate standards grounded in well-elaborated and defined understandings and definitions of Nature-Based Therapeutic interventions, for physical, mental and social rehabilitation.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Despite a comprehensive search strategy we may have omitted some relevant studies, such as studies published in other languages, grey literature or studies published elsewhere than the searched databases. Methodological concerns were noted in the included studies; these limit the clarity of the economic evaluations presented in the included studies. Notwithstanding, we believe this review contributes to clarifying the state of the affairs of economic evaluations in the growing field of therapeutic interventions integrating nature in health care.

5. Future Perspectives

The curiosity towards the field of NBT as an alternative treatment to treat different diseases is growing. Although NBT is a complex intervention with many components that can affect the outcome it is highly desirable to investigate possible additional effects of NBT. For instance, could NBT capture other patient groups than what conventional therapy is used for? Or can NBT have a more motivating effect on the participants’ desire to continue training after the intervention has ended? These are just some of the effects that could be interesting to look at in studies to come, as this also potentially is part of the economic gain of this treatment type.

In future research, it is highly desirable and recommendable to strive to achieve as high a quality and standard of clinical research as possible, based on the Consort statement [52]. Especially emphasising the sample size, randomisation of intervention versus control group, the intervention duration, frequency, intensity, and outcome measures covering as different aspects of the complex intervention as possible. Perhaps even a mixed-methods study when possible [53]. Also to include the economic evaluations following the standards of Drummond’s checklist [38] and integrating CHEER [39] for reporting already when designing the project. And finally, to include national clinical guidelines for the topic or patients’ category of interest. All in order to assure the quality of research and the economic evaluations to be reproducible and reliable.

6. Conclusions

This review reveals sparse trials within the field of NBT concerning the economic evaluation hereof. The included studies/trials all show tendencies toward a good treatment effect and positive economic effect in favour of NBT. However, they have substantial lacks in methodology and included information which affect the reliability of the results; further they are highly heterogeneous which makes comparisons difficult.

The review highlights the need for more evidence on the economic effect of NBT, which should be integrated in the study design of the future interventions and following recognised principles for economic evaluations along with rigorous study designs including control groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.B., S.S.C., L.P.K., C.B.P., U.S. and U.K.S. Data curation: H.B., L.P.K. and U.S. Formal analysis: H.B., U.S. and L.P.K. Funding acquisition: U.K.S. Methodology: H.B. Project administration: H.B. Visualisation: H.B. Writing–original draft: H.B. Writing review and editing: H.B., U.S., L.P.K., C.B.P., P.K.N., D.V.P. and U.K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The 15th of June Foundation (15. Juni Fonden), Denmark (grant number 2020-0882). The foundation had no involvement in the review.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the study funders, The 15th of June Foundation (15. Juni Fonden), because without their support this research would not have been possible. We also thank Thorbjørn Hein for proofreading and Anne Cathrine Trumpy for covidence introduction and support.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the other authors has any conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Medline search

MESH

“Horticulture”

“Horticultural Therapy”

“Outdoor rehab*” or “Outdoor healthcare” or “Outdoor intervention*” or “Green rehab*” or “Green healthcare” or “Green intervention*” or “Green care” or “Green exercise*” or “Horticulture” or “Horticulture” or “Therapeutic horticultur*” or “Social horticultur*” or “Horticultural therap*” or “Horticultural Therapy” or “Therapeutic gardening” or “Nature assisted therap*” or “Nature based therap*” or “Nature-based therap*” or “Naturebased therap*” or “Nature based intervention*” or

“Nature-based intervention*” or “Naturebased intervention*” or “Naturebased rehab*” or “Nature-based rehab*” or “Nature based rehab*” or “Ecotherap*” or “Adventure therap*” or “Nature therap*” or “Wilderness therap*” or “Garden therap*” or “Forest bathing” or “Shinrin yoku” or “Nature prescription*” or “Green prescription*” or “Nature-based recreation” or “Nature based recreation” or “Nature-based initiative*” or “Nature based initiative” or “Wildlife program*” or “Wildlife therap*”

AND

MESH

“Cost Savings”

“Cost-Benefit Analysis”

“Costs and Cost Analysis”

“Quality-Adjusted Life Years”

“Value of Life”

“Health Care Costs”

“Economic evaluation” or “Economic case” or “Economic value” or “Economic cost” or “Economic benefit*” or “Economic valu*” or “Economic impact” or “cost benefit*” or “Cost-benefit*” or “Cost-effective*” or “Cost effective*” or “Cost-Utilit*” or “Cost utilit*” or “Cost Savings” or “Cost saving*” or “Cost-Benefit Analysis” or “Cost-Benefit Analysis” or “Costs and Cost Analysis” or “Costs and Cost Analysis” or “Cost analy*” or Cost-analy* or “Social Return on Investment” or SROI or “Return on Investment” or ROI or QALY or “Quality-Adjusted Life Years” or “quality-adjusted life year*” or “Quality adjusted life year*” or “Quality-adjusted-life-year*” or “Value of Life” or “Value of Life” or “Health Care Costs” or “Health Care Costs” or Financial* or “Willingness to pay” or “Willingness-to-pay” or WTP or “Monetary value”.

References

- Duraiappah, A.K.; Naeem, S.; Agardy, T.; Ash, N.J.; Cooper, H.D.; Diaz, S.; Faith, D.P.; Mace, G.; McNeely, J.A.; Mooney, H.A.; et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Biodiversity Synthesis; A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Available online: https://www.fao.org/ecosystem-services-biodiversity/background/cultural-services/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Hatala, A.R.; Njeze, C.; Morton, D.; Pearl, T.; Bird-Naytowhow, K. Land and nature as sources of health and resilience among Indigenous youth in an urban Canadian context: A photovoice exploration. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Bragg, R.; Pencheon, D.; Wood, C.; Depledge, M.H. Improving health and well-being independently of GDP: Dividends of greener and prosocial economies. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2016, 26, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e139–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Lo, Y.Y.C.; Wong, W.H.T.; Fung, C.S.C. The associations of body mass index with physical and mental aspects of health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Results from a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer Dement. 2016, 12, 459–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Gascon, M.; Perez-Leon, D.; Mudu, P. Green spaces and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e469–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogerson, M.; Brown, D.K.; Sandercock, G.; Wooller, J.-J.; Barton, J. A comparison of four typical green exercise environments and prediction of psychological health outcomes. Perspect. Public Health 2015, 136, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.S.; Zhu, A.; Bai, C.; Wu, C.-D.; Yan, L.; Tang, S.; Zeng, Y.; James, P. Residential greenness and mortality in oldest-old women and men in China: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e17–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.A. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Nyed, P.K.; Larsen, H.B.; Fjorback, L.O. Efficacy of nature-based therapy for individuals with stress-related illnesses: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Global Heath. Mental health matters. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Brough, P.; Hague, L.; Chauvenet, A.; Fleming, C.; Roche, E.; Sofija, E.; Harris, N. Economic value of protected areas via visitor mental health. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5005–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinde, S.; Bojke, L.; Coventry, P. The Cost Effectiveness of Ecotherapy as a Healthcare Intervention, Separating the Wood from the Trees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, L.; Mayseless, O. Therapeutic factors in nature-based therapies: Unraveling the therapeutic benefits of integrating nature in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 2021, 58, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiana, R.W.; Besenyi, G.M.; Gustat, J.; Horton, T.H.; Penbrooke, T.L.; Schultz, C.L. A Scoping Review of the Health Benefits of Nature-Based Physical Activity. J. Health Eat. Act. Living 2021, 1, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, A.; Harper, N.; Carpenter, C. Outdoor Therapy: Benefits, Mechanisms and Principles for Activating Health, Wellbeing, and Healing in Nature. In Outdoor Environmental Education in Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Poulsen, D.V.; Sidenius, U.; Gramkow, M.C.; Dorthe, D.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Konceptmanual for Nacadias Naturbaserede Terapi; Copenhagen University, Institut for Geoscience and Natural Resource Management: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Corazon, S.S.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Jensen, A.G.C.; Nilsson, K.S.B. Development of the nature-based therapy concept for patients with stress-related illness at the Danish healing forest garden nacadia. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 20, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, D.V.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Davidsen, A.S. “That Guy, Is He Really Sick at All?” An Analysis of How Veterans with PTSD Experience Nature-Based Therapy. Healthcare 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Poulsen, D.V.; Bondas, T. “I look at my own forest and fields in a different way”: The lived experience of nature-based therapy in a therapy garden when suffering from stress-related illness. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1324700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, A.M. What are the components of complex interventions in healthcare? Theorizing approaches to parts, powers and the whole intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 93, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampallil, T.G.; Schauer, G.F.; Cohen, T.; Patel, V.L. Considering complexity in healthcare systems. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhury, P.; Banerjee, D. “Recovering with Nature”: A Review of Ecotherapy and Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 604440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibholm, A.P.; Christensen, J.R.; Pallesen, H. Occupational therapists and physiotherapists experiences of using nature-based rehabilitation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J.; Grbic, M.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Vukovic, O.; Toskovic, O. Nature based solution for improving mental health and well-being in urban areas. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, P.J.; Sanders, G.D. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis 2.0. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, R. Cost-benefit analysis. BMJ 1993, 307, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elley, R.; Kerse, N.; Arroll, B.; Swinburn, B.; Ashton, T.; Robinson, E. Cost-effectiveness of physical activity counselling in general practice. N. Z. Med. J. 2004, 117, U1216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindsäter, E.; Axelsson, E.; Salomonsson, S.; Santoft, F.; Ljótsson, B.; Åkerstedt, T.; Lekander, M.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. Cost-Effectiveness of Therapist-Guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Stress-Related Disorders: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendale, P.; Hansen, D.; Berger, J.; Lamotte, M. Long-term cost-benefit ratio of cardiac rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Cardiol. 2008, 63, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Twizeyemariya, A.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Niyonsenga, T.; Bogomolova, S.; Wilson, A.; O’Dea, K.; Parletta, N. Cost effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of a group-based diet intervention for treating major depression—The HELFIMED trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.L. Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions for Anxiety and Depressive Disorders; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Coventry, P.A.; Brown, J.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, P. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI É vid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinde, S.; Spackman, E. Bidirectional citation searching to completion: An exploration of literature searching methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.F.; Sculpher, M.J.; Claxton, K.; Stoddart, G.L.; Torrance, G.W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) 2022 Explanation and Elaboration: A Report of the ISPOR CHEERS II Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2022, 25, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.A.; Ratajeski, M.A.; Bertolet, M. Grey Literature Searching for Health Sciences Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Study of Time Spent and Resources Utilized. Évid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2014, 9, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J. Nature-Based Interventions and Mind–Body Interventions: Saving Public Health Costs Whilst Increasing Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsey, H.; Farragher, T.; Tubeuf, S.; Bragg, R.; Elings, M.; Brennan, C.; Gold, R.; Shickle, D.; Wickramasekera, N.; Richardson, Z.; et al. Assessing the impact of care farms on quality of life and offending: A pilot study among probation service users in England. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CJC Consulting. Branching Out Economic Study Extension. 2016. Available online: https://forestry.gov.scot/images/corporate/pdf/branching-out-report-2016.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Dayson, C.; Bashir, N.; Bennett, E.; Sanderson, E. The Rotherham Social Prescribing Service For People with Long-Term Health Conditions; Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beatton, T. The Origins of Happiness: The Science of Well-Being over the Life Course; Andrew, E., Clark, S.F., Richard, L., Nattavudh, P., George, W., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behavior. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Guo, Y.; Shenkman, E.; Muller, K. Assessing the reliability of the short form 12 (SF-12) health survey in adults with mental health conditions: A report from the wellness incentive and navigation (WIN) study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gallegos-Riofrío, C.A.; Arab, H.; Carrasco-Torrontegui, A.; Gould, R.K. Chronic deficiency of diversity and pluralism in research on nature’s mental health effects: A planetary health problem. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The CONSORT statement. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S27–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östlund, U.; Kidd, L.; Wengström, Y.; Rowa-Dewar, N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).