Abstract

Religious and spiritual (r/s) struggles entail tension and conflict regarding religious and spiritual aspects of life. R/s struggles relate to distress, but may also relate to growth. Growth from struggles is prominent in Islamic spirituality and is sometimes referred to as spiritual jihad. This work’s main hypothesis was that in the context of moral struggles, incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset would relate to well-being, spiritual growth, and virtue. The project included two samples of U.S. Muslims: an online sample from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) worker database website (N = 280) and a community sample (N = 74). Preliminary evidence of reliability and validity emerged for a new measure of a spiritual jihad mindset. Results revealed that Islamic religiousness and daily spiritual experiences with God predicted greater endorsement of a spiritual jihad mindset among participants from both samples. A spiritual jihad mindset predicted greater levels of positive religious coping (both samples), spiritual and post-traumatic growth (both samples), and virtuous behaviors (MTurk sample), and less depression and anxiety (MTurk sample). Results suggest that some Muslims incorporate a spiritual jihad mindset in the face of moral struggles. Muslims who endorse greater religiousness and spirituality may specifically benefit from implementing a spiritual jihad mindset in coping with religious and spiritual struggles.

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have investigated the beneficial effects of religion and spirituality on health and well-being (Seybold and Hill 2001; Miller and Thoresen 2003). While religious and spiritual involvement can yield various benefits, they can also be a source of struggle. Religious and spiritual (r/s) struggles transpire when a person’s beliefs, practices, or experiences regarding r/s matters cause conflict or distress (for reviews, see Exline 2013; Exline and Rose 2013; Pargament 2007; Stauner et al. 2016).

There are several forms of general r/s struggles (Exline et al. 2014). Divine struggles occur when one experiences negative thoughts or feelings about God. Demonic struggles involve concerns about being attacked by a devil or various forms of evil spirits. Interpersonal struggles refer to conflicts surrounding religious people, groups, or institutions. Moral struggles involve concerns about obedience to moral principles and guilt surrounding violations of those principles. Doubt-related struggles involve concerns about religious doubts and questions. Finally, ultimate meaning struggles involve concerns regarding a perceived absence of meaning or purpose in life (Exline et al. 2014).

Many individuals experience r/s struggles. For example, in a study of undergraduates from U.S. colleges and universities (Astin et al. 2005), a majority of first-year students reported occasionally feeling distant from God (65%) and questioning their religious beliefs (57%). Furthermore, recent studies have documented r/s struggles among diverse cultural and religious groups. For example, self-reports on the Religious and Spiritual Struggles (RSS) scale among Israeli-Jewish university students indicated as many as 30% of students experience r/s struggles (Abu-Raiya et al. 2016). Religious and spiritual struggles have also been reported among broad samples of U.S. adults (Stauner et al. 2015/2016). Using a large, nationally representative sample of adults, Ellison and Lee (2010) examined troubled relationships with God, negative social encounters within religious contexts, and chronic religious doubt and found that most people reported low levels of these struggles; nevertheless, the struggles were positively associated with psychological distress. Similarly, Abu-Raiya et al. (2015) found that, although participants that reported low levels of r/s struggle on average, all forms of struggle were positively related to depressive and anxious symptomology.

R/s struggles often imply tension and conflict regarding one’s core beliefs and behaviors. Thus, it is not surprising that many studies have found r/s struggles to be linked with psychological distress (e.g., Ellison and Lee 2010; Exline et al. 2000). A meta-analysis on religious coping and psychological adjustment revealed a direct link between r/s struggles and indicators of distress such as anxiety, anger, and depression (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005). Such links with psychological distress have been found even after controlling demographic variables such as race and socioeconomic status (Ellison and Lee 2010). R/s struggles have also been associated with greater thoughts of suicide (Exline et al. 2000), lower levels of life satisfaction (Abu-Raiya et al. 2016; Abu-Raiya et al. 2015), and less happiness, even after controlling overall religiousness, personality factors, and social isolation (Abu-Raiya et al. 2015). Although there is not enough evidence to infer a causal relationship between r/s struggles and emotional distress, research suggests a strong connection between the two domains.

In contrast to the significant body of research on the distressing aspects of r/s struggles, relatively little attention has been given to the potential of r/s struggles to promote personal growth. The existing research on the relationship between r/s struggles and growth is mixed (for a review, see Pargament et al. 2006). Although some researchers have found a connection (Pargament et al. 2000), others have not (e.g., Phillips and Stein 2007), and some studies have even found negative links between struggle and growth (e.g., Park et al. 2009). The lack of concurrent findings in the literature suggest that it may be the actual coping response to the r/s struggle, rather than the struggle itself, that predicts spiritual growth or decline (Exline and Rose 2013; Exline et al. 2017). Similarly, growth from struggle has been linked with positive religious coping (Exline et al. 2017), perception of a secure relationship with God (for a review, see Granqvist and Kirkpatrick 2013), integrating religion into everyday life (Desai 2006), having religious support (Desai 2006), and perceived support or intervention from God (Pargament et al. 2006; Wilt et al. 2017).

Although studies have demonstrated that r/s struggles can be linked with growth-related outcomes, more research needs to be conducted to examine the growth processes that could accompany r/s struggles. Looking at the process of growth from a religious perspective, individuals may intentionally embrace the experience of struggle for a greater purpose, such as for the sake of becoming closer to God or eliminating their perceived shortcomings; such struggles may be intentional in nature for the purpose of spiritual growth. People of faith who may desire to become more devoted believers may embrace struggle as a medium through which they can develop a stronger relationship with the Divine. Struggling for growth purposes is prominent in the religion of Islam, and is sometimes referred to as spiritual jihad. Hence, a natural place to initiate an empirical investigation of such processes is within the context of the religion of Islam.

1.1. Spiritual Jihad: An Islamic Perspective

Much of the research conducted on r/s struggles has made use of predominantly Christian samples. The aim of the current project was to focus primarily on struggles and growth among Muslims, framed in terms of spiritual jihad. A brief review of relevant Islamic theology and psychological research will be addressed. The Arabic noun “jihad” is derived from the Arabic verb “jahada”, which is translated as “struggle” or “hardships” (Al-Khalil 1986). Some traditions within Islam, such as the Sufi tradition, categorize jihad into two types: the greater and the lesser jihad. The greater jihad (al-jihad al-akbar), contrary to popular thought, refers to an internal spiritual struggle in the path of God against the various trials of life (Nizami 1997). On the other hand, the lesser jihad (al-jihad al-asghar) refers to an external endeavor for the sake of Islam (Al-Zabidi 1987). Examples of the lesser jihad include fighting for God’s cause on the battlefield, stepping out of a conversation due to religious objections, or speaking out for God’s sake. Notably, the lesser jihad (often simply referred to as “jihad”) has become increasingly aligned with popular views of Muslims in recent years (Amin 2015; Afsaruddin 2013). The term jihad has particularly become increasingly associated with acts of terrorism, thereby promoting the notion that terrorism is a fundamental aspect of Islam (Turner 2007). Such interpretations of the term jihad not only ignore the majority of forms of the lesser jihad that are completely nonviolent, but also fail to acknowledge the meaning of greater jihad for many Muslims. Islamic spirituality, as reflected largely in the Sufi heritage, considers the greater spiritual jihad a fundamental component of spiritual growth and development. Spiritual jihad is a process that requires a conscious effort in “struggling against the soul (al-nafs) for the sake of God” (Picken 2011). In Islam, the nafs are thought to be responsible for a wide variety of dangerous, unsocialized impulses; this psychological influence is roughly analogous to the Freudian (1923/1962) concept of the id. For further information regarding the role of the nafs in the process of spiritual jihad, please request a copy of Saritoprak et al. (2018).

The ongoing journey of spiritual jihad may be a common experience among practicing Muslims. Numerous Qur’anic verses promote an intentional, continuous engagement in spiritual jihad, such as these: “And those who strive for us, we will surely guide them to our ways. And indeed, Allah is with the doers of good” (29:69), and, “The ones who have believed, emigrated, and striven in the cause of Allah with their wealth and their lives are greater in rank in the sight of Allah. And it is those who are the attainers [of success]” (9:20). Similarly, as narrated by Al-Bayhaqi (1996), after a successful defeat and arrival from the Battle of Badr, Prophet Muhammad stated, “We have returned from the lesser jihad to the greater jihad.” When his companions inquired about the greater jihad’s meaning, the Prophet replied, “It is the struggle that one must make against one’s carnal self (nafs).” As the Day of Judgment is one of the six articles of the Islamic faith, practicing Muslims often engage in a conscious examination of their nafs with the aim of striving to better themselves as believers in return for not only an eternal afterlife, but also for the sole sake of God. Thus, introspection regarding one’s behaviors, words, and thoughts throughout life on earth promotes a sense of preparedness for the final Judgment and a path toward spiritual refinement.

Nevertheless, despite the theological emphasis on spiritual jihad within Islam, no study to date has examined the construct of spiritual jihad within the field of psychology. A review of the current literature on r/s struggles and growth indicates a gap in both the conceptualization and measurement of spiritual jihad. As a preliminary attempt to address this gap, the aim of the current article is to investigate the process by which individuals engage in spiritual jihad and the outcomes associated with such engagement.

1.2. Spiritual Jihad: Attributing Wrongdoings to the Nafs

Attribution theory (Weiner 1985) emphasizes the need to assign responsibility for events. In the face of certain events, people often look for information regarding the cause of why an event occurred, and this is especially true for unexpected and negative events. In such cases, people may often think, “Why did this event occur?” or, “Why did I do what I did?” in attempting to explain why a particular incident took place. By seeking knowledge to explain certain outcomes, including successes and failures, the individual can learn to adapt their behavior accordingly in order to prevent or promote a certain incident in the future.

This line of research is relevant to the concept of spiritual jihad. Within a spiritual jihad framework, Muslims who are faced with certain desires or temptations may attribute such inclinations to their nafs. For example, one may think, “I have a sexual desire because my nafs wants it.” Along similar lines, in the face of perceived wrongdoings or moral failures, a Muslim may think, “I engaged in the behavior because of the desires of my nafs”, thereby attributing either thoughts or actions to such proclivities of their nafs. By attributing certain thoughts and behaviors to their nafs, Muslims incorporating a spiritual jihad approach into their life may be more likely to become aware of such inclinations in the future and engage in greater efforts in struggling against such desires. Speculatively speaking, cognitively separating the source of motivation for undesirable behaviors from one’s own consciousness may help Muslims resolve cognitive dissonance and reject their unwanted impulses.

1.3. Spiritual Jihad and Positive Religious Coping

The mechanism of meaning-making may play a role in positive emotional experiences (Folkman 1997). Because religious and spiritual beliefs and practices may play a significant role in making meaning (e.g., Park 2012), they can also be major component of the coping process (Pargament 1997). Religious coping has been proposed to play five main functions: providing a sense of comfort in times of struggle, bringing a feeling of connectedness with others, bringing meaning to a distressing life experience, providing a framework for controlling events that are beyond one’s direct personal control and resources, and providing help in making life transformations (Pargament et al. 2000). Additionally, religious coping may take both positive and negative forms.

Positive religious coping may involve being spiritually connected with the world and others, having a secure relationship with God, and/or finding a greater meaning in life (Pargament et al. 1998). On the other hand, negative religious coping methods may reflect religious/spiritual struggles such as being spiritually discontent, appraising a stressor as a punishment from God, viewing the stressor as an act of demonic forces, and/or being dissatisfied with other religious people or institutions (Pargament et al. 1998). Research has shown that negative and positive forms of religious coping can exhibit differing outcomes related to mental and physical health (e.g., Hebert et al. 2009; Trevino et al. 2010). For example, negative religious coping has been associated with greater symptoms of depression and lower quality of life, whereas positive religious coping has been linked with lower levels of psychological distress and greater well-being (Pargament et al. 1998).

Similarly, spiritual jihad may be framed as a form of positive religious coping. It may be a way in which some Muslims approach life experiences and a process that fosters making meaning of negative life events and coping in a proactive manner. In the face of adversities and struggle, Muslims may appraise the situation through a spiritual jihad-based interpretive lens. For example, they may regard a distressing life event as a test that will bring them closer to their faith, a test of their nafs that they must overcome, a way in which they can earn greater sawab (good deeds) in the afterlife, or an opportunity to ask for Divine forgiveness. Incorporating such a mindset may allow the individual to make meaning of their experience in a positive manner, and may promote perceptions of spiritual growth. Within the writings of some Islamic scholars, spiritual jihad has been considered an essential component of spiritual growth (Al-Ghazali 1982; Al-Bursawi 1990). It requires a constant and conscious struggle against one’s nafs with the aim of developing a closer relationship with God and becoming a more devout Muslim.

1.4. Spiritual Jihad: Implications for Virtues, Vices, and Well-Being

Spiritual jihad is not only intended to promote positive religious coping, but it is also intended to promote virtues. From an Islamic perspective, there are several overarching themes rooted in the Qur’an and Sunnah of the Prophet that promote actively bettering oneself in the path of God through virtuous behavior. For the purpose of this study, we will focus on patience, gratitude, and forgiveness with an emphasis on their potential links with spiritual and psychological well-being.

The cultivation of sabr (often translated from Arabic as “patience”), is an essential component in the active engagement of spiritual jihad. Differing from the traditional understanding of the English word patience, in the Islamic tradition, sabr can essentially be described as the active restraining of oneself from wrongdoings, limiting objections and complaints in the face of calamities, and putting all trust in God (Khan 2000). In order to ensure that we use the term as close as possible to the original Arabic term, herein, a nuanced presentation of the word patience is the most accurate way to present the information. One of the earliest examples of patience in Islamic history can be traced back to the time when the Prophet was being persecuted by the pagan Meccans of the time. During such times of hardship, the Qur’anic verse, “And whoever is patient and forgives…indeed, that is of the matters [requiring] determination” (42:42–43) encouraged Muslims to maintain a steadfast approach and patiently endure wrongdoings in a forgiving and non-combative manner (Afsaruddin 2007). From a psychological perspective, approaching situations in a patient manner enhances resilience in times of hardship, thereby promoting better coping ability (Connor and Zhang 2006). The act of being patient involves a proactive approach in coping with negative emotions such as anger and frustration. Therefore, it may encourage a less hostile approach to life experiences, a positive perspective, and increased resilience in the face of adversity.

Gratitude, referred to as shukr in Arabic, is an essential aspect of Islamic spirituality. Gratefulness towards God and other people is reflected through one’s appreciation and acknowledgement of the surrounding blessings. Gratitude is a manner through which one remembers God and brings a religious perspective of life to conscious awareness, which may be regarded as a vital component of spiritual jihad. Numerous themes of gratitude can be found in the Qur’an and hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad). For example, an emphasis on gratitude is evident in such sayings of the Prophet: “One who does not thank for the little does not thank for the abundant, and one who does not thank people does not thank God” (Al-Muslim 2006; hadith 2734). Psychological literature has considered gratitude to be a part of one’s larger framework of life that fosters noticing and appreciating the positive in the world (Wood et al. 2010). Gratitude has also been linked with less anger and hostility and with more warmth, altruism, and trust (Wood et al. 2008), in addition to greater happiness and positive affect (e.g., Emmons and McCullough 2003; Watkins et al. 2003).

The act of forgiving can be regarded as an inevitable aspect of one’s spiritual jihad and holds a distinguished place in Islamic theology. As humans are vulnerable to sins, mistakes, and transgressions, forgiveness promotes an opportunity for spiritual reformation. The act of forgiving fosters both one’s relationship with God and with other humans. The Qur’an highlights both God’s forgiveness and the act of forgiving others, as evident in the verse: “And let not those of virtue among you and wealth swear not to give [aid] to their relatives and the needy and the emigrants for the cause of Allah, and let them pardon and overlook. Would you not like that Allah should forgive you? And Allah is forgiving and merciful” (24:22). Within psychology, forgiveness has been studied as a positive and prosocial response to transgressions (for reviews, see Fehr et al. 2010; Riek and Mania 2012; Worthington 2005). Historically, researchers have found that individuals who tend to forgive others are more altruistic, caring, generous, and empathic (Ashton et al. 1998). More recent studies show that people who forgive are more likely to be in relationships described as “close”, “committed”, and “satisfactory” (Tsang et al. 2006). For a more detailed overview of virtues rooted in the Qur’an and Sunnah, please request a copy of Saritoprak et al. (2018).

Forgiveness can also take the form of self-forgiveness. Research has shown a positive association between self-forgiveness and perceived forgiveness from God (Martin 2008; McConnell and Dixon 2012). Feeling unforgiven by God may contribute to one’s general view of the self (e.g., feeling unworthy) and/or of God (e.g., punitive and angry). Such experiences may form r/s struggles (Exline et al. 2017) and adversely impact an individual’s spiritual and mental wellness. This possibility suggests another way in which forgiveness may facilitate growth: if taking a spiritual jihad mindset toward one’s r/s struggles can help a person feel forgiven by God, that perception may then lead to self-forgiveness and allow healing to occur.

In addition to promoting virtuous behaviors, the greater jihad also fosters an active strife against the everyday malevolent temptations of the nafs as a means towards improving the self in the way of God. The individual must struggle to control sinful desires for the purpose of gaining God’s favor and eternal Paradise, as evident in the verse, “But as for he who feared the position of his Lord and prevented the soul from [unlawful] inclination, then indeed, paradise will be [his] refuge” (79:40–41). Such a strife can take form against the many evils the Qur’an and Sunnah put forward. For example, the Qur’an presents numerous verses on the consequences of exhibiting arrogance and pride, such as, “And do not turn your cheek [in contempt] toward people and do not walk through the earth exultantly. Indeed, Allah does not like everyone self-deluded and boastful” (31:18). Similarly, other vices are also cautioned against among the Qur’anic verses and the life of the Prophet. For example, the Qur’an states “So fear Allah as much as you are able and listen and obey and spend [in the way of Allah]; it is better for yourselves. And whoever is protected from the stinginess of his soul—it is those who will be the successful” (64:16) highlights the strife to deter oneself from sinful traits such as greed and stinginess. Similarly, the saying of the Prophet “Do not spy upon one another and do not feel envy with the other, and nurse no malice, and nurse no aversion and hostility against one another. And be fellow-brothers and servants of Allah” (Al-Bukhari 1990) discourages Muslims from vices such as envy and hatred.

1.5. The Present Study

We are not aware of any empirical studies that have examined spiritual jihad, a growth-oriented mindset that Muslims may bring to r/s struggles. Our aim was to attempt to assess the mindset associated with spiritual jihad and to begin to examine its associations with perceptions of personal growth (including spiritual and posttraumatic growth), well-being, and virtues among U.S. Muslims. Although a mindset of spiritual jihad could be brought to almost any type of r/s struggle, we began with an emphasis on moral struggles, because these are struggles in which an internal conflict against one’s unwanted inclinations would be especially salient.

1.6. Hypotheses

We expected positive associations between endorsement of a spiritual jihad mindset and two indicators of religious engagement: general religiousness and daily spiritual experiences with God while controlling social desirability. In response to a specific moral struggle, we hypothesized that greater endorsement of a spiritual jihad mindset would relate to higher levels of positive religious coping, spiritual growth, posttraumatic growth, and lower levels of spiritual decline. In terms of general well-being, we expected that endorsement of the spiritual jihad mindset would be associated with greater life satisfaction and fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression. Finally, we predicted that endorsement of the spiritual jihad mindset would be associated with reports of more virtuous behaviors in terms of greater endorsement of traits related to patience, forgiveness, and gratitude. All hypotheses were preregistered with the Open Science Framework (Saritoprak and Exline 2017a, embargoed until 2021).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

We included participants from two samples. The first was an adult Muslim sample (N = 280) obtained from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) website. The second sample was comprised of an adult Muslim community sample (N = 74). To obtain the community sample, we contacted Muslim leaders throughout Northeast Ohio via email and asked them to forward an invitation to members of their congregations. All participants completed a battery of questionnaires assessing predictor and outcome variables related to spiritual jihad. Participants read the consent form prior to initiating the questionnaires and received a small monetary incentive for their participation (MTurk participants received $3; community participants received $10 to mitigate recruitment difficulty).

Table 1 summarizes demographic information for both samples. Both samples were comprised mostly of Middle Eastern participants, with the median age for both samples being in the range of early thirties to mid thirties. The participants in the MTurk sample comprised a larger percent of U.S.-born participants compared to the community sample, in addition to more participants identifying as single. In terms of English language proficiency, both samples were composed predominantly of native English speakers, followed by advanced English speakers.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographics.

2.2. Measures

Table 2 (which appears at the start of the Results section) lists descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, ranges) for all study variables. For a brief description of all of the measures, please see Appendix B.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and differences between MTurk and community samples for main study variables.

Demographic questionnaire. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire. The items provided further information on participants’ genders, ages, religious/spiritual traditions, ethnicities, places of birth, relationship statuses, years of residence in the United States, and degrees of proficiency in the English language.

We initially developed a 16-item measure to examine the extent to which participants endorse a spiritual jihad interpretive framework in reference to a specific struggle. Note that spiritual jihad is our technical term for the Islamic concept; items did not use the term “jihad” to avoid unwanted connotations. Items were sent to academic scholars in the field of Islamic spirituality in order to develop content validity. The three scholars provided feedback regarding the content of items. Feedback from the scholarly experts primarily involved suggestions towards developing a working definition of the term spiritual jihad, translating Arabic terminology, and the rewording of items to better align with an Islamic framework. Participants were instructed to rate each item on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) pertaining to how they viewed a specific moral struggle they recently encountered. Sample items included “It is a test that will make me closer to God” and “It is a desire of my nafs that I must work against.” Reverse-scored items such as “The struggle has no meaning for me” and “Allah plays no role in my struggle” were also included in the measure to address issues of response biases (e.g., acquiescence). As detailed in the results section, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the structure of the measure. One item was dropped as a result of the analysis, as described in the results section. The current study provided initial tests of this new measure’s reliability and validity. See Appendix A for the complete measure.

Religious coping was measured with select, abbreviated (three-item) subscales from the Religious Coping Questionnaire (RCOPE; Pargament et al. 2000). The RCOPE consists of subscales assessing coping responses to stressful experiences within a religious context including Benevolent Religious Appraisal (e.g., “Thought the event might bring me closer to God”), Active Religious Surrender (e.g., “Did my best and turned the situation over to God”), Seeking Spiritual Support (e.g., “Looked to God for strength, support, and guidance”), Religious Focus (e.g., “Prayed to get my mind off problems”), Religious Purification (e.g., “Asked forgiveness for my sins”), Spiritual Connection (e.g., “Looked for a stronger connection with God”) and Religious Forgiving (e.g., “Sought help from God in letting go of my anger”). Subscale average scores and an overall average score were examined.

Islamic religiousness was measured with the five Islamic Dimensions subscales of the Psychological Measure of Islamic Religiousness (PMIR; Abu-Raiya et al. 2008): Beliefs Dimension (e.g., “I believe in the Day of Judgment”), Practices Dimension (e.g., “How often do you fast?”), Ethical Conduct-Do Dimension (e.g., “Islam is the major reason why I honor my parents”), Ethical Conduct-Do Not Dimension (e.g., “Islam is the major reason why I do not drink alcohol”), and Islamic Universality Dimension (e.g., “I identify with the suffering of every Muslim in the world”). An average score was obtained from each subscale, in addition to an overall average score, in order to measure levels of Islamic religiousness.

Daily spiritual experiences were measured with the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Underwood and Teresi 2002). The DSES examines spiritual experiences such as a perceived connection with the transcendent (e.g., “I feel God’s presence”). Our focus was on the first 15 items, which were presented in the form of a six-point scale (1 = never, or almost never, 6 = many times a day). The word “Allah” was substituted for “God” for the purpose of the current study. An overall average score was obtained, with larger scores indicating greater perceived closeness with Allah.

The short form of the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-S; Calhoun and Tedeschi 1999) assessed the extent to which participants perceived themselves as having grown from their reported crisis with 13 items (e.g., “A willingness to express my emotions”). Ratings were averaged.

Spiritual growth and decline were measured via abbreviated versions of the Spiritual Growth (e.g., “Spirituality has become more important to me”) and Spiritual Decline (e.g., In some ways I have shut down spiritually”) subscales of the Spiritual Transformation Scale (STS; Cole et al. 2008). A shortened version of the STS (eight items), using the highest-loading items from each subscale, was administered for the current study, with permission from the scale author. Similar shortened forms have been used in other published studies of religious/spiritual struggles (Exline et al. 2017; Wilt et al. 2016). Participants were asked to rate their degree of agreement regarding spiritual growth and decline on a seven-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very true). An overall average score was calculated for both subscales.

The five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) was used in order to measure satisfaction with life (e.g., “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life”). Participants responded to items on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). An overall score was obtained from all five items, including reverse-scored items, with higher scores indicating greater self-reported life satisfaction.

Generalized anxiety was measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006). The GAD-7 assesses generalized anxiety symptoms by asking participants to report their frequency of anxiety-related concerns (e.g., “Worrying too much about different things”) on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores were summed.

Depressed mood was assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Short Form (CES-D-10; Radloff 1977), which includes 10 items (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me”). Participants responded to statements measuring depressive symptoms in the past week on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all of the time). Ratings were summed.

Dispositional gratitude was measured with the Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form (GQ-6; McCullough et al. 2002). Participants responded to six items addressing gratefulness (e.g., “I have so much in life to be thankful for”). Items were answered on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Item ratings were summed.

A general tendency to forgive was measured with the Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS; Thompson and Snyder 2003), a self-report questionnaire with 18 items (e.g., “Learning from bad things that I’ve done helps me get over them”). Participants responded on a scale ranging from 1 (almost always false of me) to 7 (almost always true of me). An overall scale score was calculated from ratings of the 18 items, including reverse-scored items.

Patience was measured with the 3-Factor Patience Scale (3-FPS, Schnitker 2012). The scale is comprised of 11 items (e.g., “I am able to wait-out tough times”). A composite patience score was calculated by summing ratings of all items, including reverse-scored items.

Social desirability: the five-item short form of the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS; Reynolds 1982) was included. Items (e.g., “No matter whom I am talking to, I am always a good listener”) were rated true or false. The MCSDS has exhibited good internal consistency and test-retest reliability in prior research (Reynolds 1982). Ratings were summed, including reverse-scored items, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of socially desirable responses.

3. Results

All analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team 2017) using the psych (Revelle 2017), robustbase (Maechler et al. 2018), lmtest (Zeileis and Hothorn 2002), and car (Fox and Weisberg 2011) packages.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Frequency and descriptive statistics for the demographics and main variables were examined for the MTurk and community samples. Participants were asked to skip any questions they may feel uncomfortable answering. The ability to skip items resulted in increased missing data and lower sample sizes for various variables, particularly within the community sample. In the interest of validity, we eliminated participant responses reporting no current moral struggles and/or responding in incomprehensible ways to qualitative items (MTurk, n = 39; Community, n = 12). Preliminary analyses were performed to examine any violations of the assumptions of approximate normality. Negligible violations of normality (defined provisionally as skew and excess kurtosis ≤ 1) were observed within the MTurk sample. However, substantial violations of normality were observed (in spiritual decline, Islamic religiousness, gratitude, and daily spiritual experiences) within the community sample. In this sample, the distribution of spiritual decline had a skewness of 1.11 and kurtosis of 0.32 (i.e., excess kurtosis, which is ordinary kurtosis −3; we only refer to this excess kurtosis throughout this report). Islamic religiousness had a skewness of −1.63 and kurtosis of 3.48. Gratitude had a skewness of −1.43 and kurtosis of 1.78. Daily spiritual experiences had a skewness of −1.01 and kurtosis of 1.19. Square root transformations (except daily spiritual experiences, which was squared) reduced skew and kurtosis to less than one in magnitude for all four variables.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the main variables. Mann–Whitney U tests evaluated the evidence for any tendency of either population to score higher or lower than the other on each variable. A Benjamini and Yekutieli (2001) correction maintained α = 0.05 across this set of dependent pairwise comparisons. Specifically, in comparison to those in the MTurk sample, participants in the community sample endorsed higher levels of incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset when approaching struggles. Similarly, they reported greater religiousness and higher levels of daily spiritual experiences and life satisfaction. Those in the community sample were also significantly more likely to endorse dispositions toward forgiveness and gratitude. Finally, the community sample participants indicated lower levels of spiritual decline.

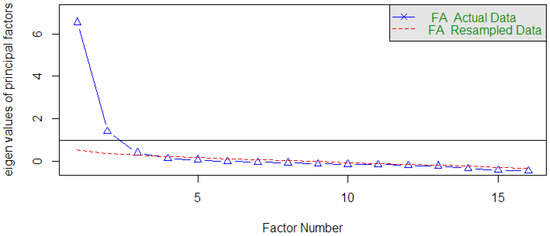

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

All 16 items from the spiritual jihad mindset questionnaire (MTurk sample) were entered into an exploratory factor analysis using ordinary least squares estimation from a polychoric correlation matrix. (A factor analysis was not conducted with the community sample data due to the small sample size.) The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin overall measure of sampling adequacy value was 0.92, indicating excellent factorability. Barlett’s sphericity test of the polychoric correlation matrix rejected the null hypothesis (χ²(120) = 2340, p < 0.001), further supporting the factor analysis. The first and second eigenvalues (6.5 and 1.4, respectively) substantially exceeded the others (eigenvalues 3–16 < 0.5), which did not differ meaningfully from each other or from resampled eigenvalues in parallel analysis (all differences < 0.3; see Figure 1). This test indicated that a two-factor model accounts for the majority of variance (51%) with optimal efficiency and parsimony.

Figure 1.

Scree plot and parallel analysis.

Examination of direct oblimin-rotated factor loadings revealed one item (i.e., “I believe this struggle is ultimately weakening my faith”) that had a weak factor loading (λ = 0.38). This item was dropped from the overall measure, which improved its average interitem correlation ( = 0.03). A second factor analysis of the remaining 15 items revealed that two factors explained 54% of the variance. This model fit the data acceptably (Tucker–Lewis index = 0.908, RMSEA = 0.085, root mean square of residuals corrected for degrees of freedom = 0.05). The first factor ( = 5.40) explained 36% of the variance, and the second factor ( = 2.72) explained 18% of the variance. Table 3 shows all items’ factor loadings, which exhibit fairly simple structure (all primary λ > 0.5, all secondary |λ| < 0.2). Overall, these results were compatible with the theoretical framework proposed in development of the measure, although a second factor was not anticipated. Conceptually, we interpreted the two factors as endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset (SJM) and rejecting a SJM, respectively. These factors correlated negatively and strongly (r = −0.50, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Summary of the exploratory factor analysis of the spiritual jihad measure using ordinary least squares estimation from a polychoric correlation matrix and direct oblimin rotation.

3.3. Internal Consistency

Results from the factor analysis were used to generate subscales. Estimates of omega total were calculated for the factor analytically derived subscales. The Endorsing a Spiritual Jihad Mindset subscale revealed excellent internal consistency (ωtotal = 0.91). The Rejecting a Spiritual Jihad Mindset subscale revealed good internal consistency (ωtotal = 0.82). With both subscales combined after reversing the coding of responses to items on the Rejecting a Spiritual Jihad Mindset subscale, the total measure revealed excellent internal consistency (ωtotal = 0.92). This total score is presented as a composite that represents the overall consistency of responses with a spiritual jihad mindset—both endorsing and not rejecting it—rather than as a unidimensional latent factor, since the factor analysis indicated greater complexity than that. Item-total correlations (calculated from the polychoric correlation matrix with corrections for item overlap and scale reliability) were between 0.48 and 0.78. If the complexity was due to acquiescence bias or true ambivalence or indifference, then the distinctions between these possibilities were largely set aside in the composite score, which would have represented each of these configurations as middling scores. To best enable multiple interpretive perspectives, many of the analyses below will be examined in reference to both the two subscales and the total composite score. Each score was calculated by coding response options as consecutive integers (1–7) and averaging responses across items. Items on the Rejecting a Spiritual Jihad Mindset subscale were reverse-coded for the purposes of calculating composite scores.

3.4. Spiritual Jihad, Daily Spiritual Experiences, and Islamic Religiousness

Associations of the spiritual jihad mindset with Islamic religiousness and daily spiritual experiences were estimated as Pearson product–moment correlations (Table 4). As predicted, results within the MTurk sample revealed that incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset correlated significantly and positively with Islamic religiousness and daily spiritual experiences. Similar results were found among participants in the community sample.

Table 4.

Pearson product–moment correlations between the Spiritual Jihad Measure and main variables.

The spiritual jihad mindset composite was regressed onto Islamic religiousness (β = 0.35, t(262) = 4.41, and p < 0.001) and daily spiritual experiences (β = 0.37, t(262) = 4.18, and p < 0.001) simultaneously (adjusted R2 = 0.44) by using the iteratively reweighted least squares estimation (by default a bisquare redescending score function with other defaults suggested in Koller and Stahel 2017), revealing independent predictive effects. This model’s residuals approximated a normal distribution (|skew| and |kurtosis| = 0.11) and passed a test of independence (H0: no first-order autocorrelation; Durbin–Watson d = 2.2, p = 0.210). A Breusch–Pagan test retained the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity (χ²(2) = 0.70 and p = 0.703). The variance inflation factor (VIF = 2.3) indicated minimal multicollinearity. Effects appeared roughly linear, though exploratory analysis of a third-order polynomial model suggested positive quadratic (β = 0.19, t(262) = 4.24, and p < 0.001) and cubic (β = 0.10, t(262) = 3.42, and p < 0.001) effects of Islamic religiousness could partly explain and reduce its linear effect (β = 0.20, t(262) = 1.80, and p = 0.073) while improving the model fit significantly (robust Wald χ²(2) = 19.3, p < 0.001; ∆R²adj. = 0.04). Despite this model’s robustness to high-leverage and outlying observations, the curvilinear effects seemed to reflect the influence of a few very low scores in both Islamic religiousness and the spiritual jihad mindset, which strengthened their positive relationship at low levels of both factors. The sparseness of data at these low levels and the exploratory nature of this model precluded confident interpretation of curvilinear effects, and the model’s close resemblance to a linear relationship above low levels favored the originally predicted model of simple main effects.

Slightly stronger results were found within the community sample, where both Islamic religiousness (β = 0.55, t(47) = 6.34, and p < 0.001) and daily spiritual experiences (β = 0.30, t(47) = 3.29, and p = 0.002) predicted unique variance in the spiritual jihad mindset composite (R2adj. = 0.67). This model’s residuals were somewhat leptokurtic (kurtosis = 1.49), but independent (d = 2.1 and p = 0.734) and homoskedastic (χ²(2) = 4.07 and p = 0.131). This model had minimal multicollinearity (VIF = 1.7), and exploratory alternatives yielded insignificant evidence of any curvilinear effects.

Partial correlation analysis was used to explore the relationship between Islamic religiousness and endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset, while controlling scores on the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale within the MTurk and community samples. There was a strong, positive, partial correlation between Islamic religiousness and endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset when controlling social desirability (MTurk sample: r(264) = 0.61, p < 0.001; community sample: r(43) = 0.69, p < 0.001). Similar results were found between Islamic religiousness and participants’ composite spiritual jihad mindset score (MTurk sample: r(264) = 0.60, p < 0.001; community sample: r(43) = 0.70, p < 0.001).

3.5. Spiritual Jihad and Religious Coping

Correlations between a spiritual jihad mindset and various forms of positive religious coping (as measured by subscales of the RCOPE) were investigated (see Table 5). As expected, there were moderate to strong, positive correlations between incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset and positive religious coping subscales, with high levels of a spiritual jihad mindset associated with higher levels of all forms of positive religious coping within both the MTurk and community samples, indicating strong support for the hypotheses. Similar results were found in regard to participants’ composite spiritual jihad mindset scores. Consistently, rejecting a spiritual jihad mindset was significantly negatively correlated with all forms of positive religious coping within both samples (except religious purification coping in the community sample: r(61) = −0.23, p = 0.07).

Table 5.

Pearson product–moment correlations between the Spiritual Jihad Measure and Forms of Positive Religious Coping.

3.6. Spiritual Jihad, Growth, and Decline

As expected, significant, fairly strong, positive correlations with post-traumatic growth were found for the spiritual jihad mindset endorsement subscale and composite score in both the MTurk and community samples (Table 4). Also as expected, in the MTurk sample, a significant, moderate, negative correlation was found between the spiritual jihad mindset composite and spiritual decline, whereas rejecting a spiritual jihad mindset was positively associated with spiritual decline. Though negative in valence as hypothesized, these same correlations in the community sample between one’s spiritual jihad mindset scores and spiritual decline did not differ from zero significantly.

Within the MTurk sample, endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset was found to predict spiritual growth strongly and positively (β = 0.48, t(265) = 6.05, and p < 0.001) after controlling Islamic religiousness (β = 0.26, t(265) = 2.83, and p = 0.005; R²adj. = 0.45, ∆R²adj. = 0.13). Likewise, within the community sample, endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset predicted greater spiritual growth strongly, significantly (β = 0.60, t(49) = 4.81, and p < 0.001), and independently of Islamic religiousness, which had essentially no independent effect (β = 0.04, t(49) = 0.26, and p = 0.793; R²adj. = 0.38, ∆R²adj. = 0.17), though its bivariate correlation was strong (β = 0.47 as the only predictor in robust regression, t(50) = 3.57, and p < 0.001). However, these models’ residuals exhibited heteroskedasticity (MTurk χ²(2) = 10.99, p = 0.004; community χ²(2) = 1.86, p = 0.400, but a pattern was visible in a scatterplot of residuals vs. fitted values; also, community residuals’ kurtosis = −1.1), and spiritual growth in the community sample was predicted slightly better by an exploratory model with a negative quadratic effect of Islamic religiousness (β = −0.08, t(48) = −2.02, and p = 0.049; linear β = −0.09, t(48) = −0.58, and p = 0.568; R²adj. = 0.39; ∆R²adj. = 0.01, Wald χ²(1) = 4.1, and p = 0.043). These violations of regression assumptions (linear effects and homoskedastic, normally distributed residuals) may have biased the model’s primary results.

Similar results were found when examining the prediction of post-traumatic growth. Endorsing a spiritual jihad mindset was found to explain additional unique variance in post-traumatic growth after controlling Islamic religiousness within the members of the MTurk sample (β = 0.47, t(264) = 5.64, p < 0.001, R² = 0.31) and the community sample (β = 0.67, t(48) = 3.48, p = 0.001, R²adj. = 0.27). These models met all regression assumptions (|skew| and |kurtosis| of residuals < 1, Breusch–Pagan and Durbin–Watson p > 0.05, VIF < 5) except linearity of effects; an exploratory alternative improved the MTurk model with a quadratic effect of spiritual jihad endorsement (β = 0.13, t(263) = 4.11; linear β = 0.51, t(263) = 6.32; both p < 0.001; ∆R²adj. = 0.03, Wald χ²(1) = 16.9, p < 0.001).

3.7. Spiritual Jihad, Psychological Well-Being, and Life Satisfaction

When controlling Islamic religiousness, endorsement of a spiritual jihad mindset showed negative, significant, partial correlations with both anxiety and depression in the MTurk sample, but not in the community sample (Table 6). No significant correlations were found between life satisfaction and incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset within either sample.

Table 6.

Partial Pearson product–moment correlations between spiritual jihad scores, depressive symptoms, and anxiety, controlling Islamic religiousness.

3.8. Spiritual Jihad and Virtues

The correlations between a spiritual jihad mindset and virtuous behaviors such as patience, forgiveness, and gratitude were investigated. Results in the MTurk sample revealed significant, positive correlations between all virtues, patience, forgiveness, and gratitude (Table 7) and incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset, thereby providing support for hypotheses. Similarly, rejecting a spiritual jihad mindset correlated significantly and negatively with all virtues, patience, forgiveness, and gratitude in the MTurk sample. No significant correlations were found within the community sample.

Table 7.

Pearson product–moment correlations between the Spiritual Jihad Measure and virtues.

4. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to investigate the process of approaching moral struggles with a spiritual jihad mindset among Muslims living in the United States, and the outcomes associated with incorporating such a mindset. One aim was to create a new measure to assess the construct of spiritual jihad. Participants were obtained from two samples: an online platform (MTurk) and a community sample. The following sections will examine key findings of the current study, in addition to research and practical implications, and limitations and directions for future research.

4.1. Key Findings

The results of the current study provided preliminary support for the Spiritual Jihad Measure. An exploratory factor analysis revealed a two-factor solution (Endorsing SJ Mindset, Rejecting SJ Mindset). Both subscales showed good to excellent internal consistency. Examining the measure, the two subscales and the total composite scale provided complementary results regarding associations. Though we reported results using both the individual subscales and the composite scale for completeness, we suggest using the composite scale to measure respondents’ overall consistency with the spiritual jihad mindset in general applications of this measure. Internal consistency was still very good when the subscales were combined, and the inclusion of both Endorsing SJ and Rejecting SJ items may help to mitigate any influence of acquiescence bias on total scores. However, this scoring system conflates general non-endorsement (i.e., low scores on both subscales) with ambivalence (high scores on both), which might represent legitimate perspectives on the spiritual jihad mindset rather than acquiescence bias. The moderate correlation between the subscales implies that such perspectives may not be rare. Therefore, methodologists and any researchers with interests in ambivalence toward the spiritual jihad mindset or the potential for acquiescence bias in its measurement should consider the endorsement and rejection factors separately or within a bifactor model.

The findings of the present study revealed that Islamic religiousness and daily spiritual experiences both significantly predict incorporating a spiritual jihad mindset when Muslims face moral struggles, even when controlling social desirability. These close associations between greater religious devotion and a spiritual jihad mindset are consistent with the construct of spiritual jihad, which implies a conscious effort in striving to become a more devout Muslim by working against the temptations and desires of the nafs. Furthermore, the results indicated that Muslims in both samples who endorsed higher levels of a spiritual jihad mindset were more likely to make use of positive religious coping. For example, they were more likely to see stressors as beneficial for them or to view stressors as part of God’s plan. The findings provided strong support for the hypotheses in the current study.

A further key finding was that Muslims in both samples who endorsed a spiritual jihad mindset when faced with moral struggles also reported greater levels of perceived spiritual and post-traumatic growth. Importantly, the results remained significant even after controlling Islamic religiousness, implying that a spiritual jihad mindset may be contributing additional unique variance in Muslims’ perceived spiritual and post-traumatic growth experiences. Although research on the relationship between r/s struggles and growth is mixed, the current findings add preliminary evidence to proposed suggestions in the literature that the actual response to the r/s struggle, rather than the struggle itself, may be what predicts spiritual growth or decline (Exline and Rose 2013; Exline et al. 2016; Wilt et al. 2017). Similar results emerged in regard to the association between a spiritual jihad mindset and perceived spiritual decline. As expected, Muslims in the MTurk sample who were more likely to endorse a spiritual jihad mindset were also less likely to endorse perceived spiritual decline. However, this relationship was not clear for participants in the community sample.

In terms of mental health outcomes, results revealed negative associations between participants’ spiritual jihad mindset scores and their levels of anxious and depressive symptoms, as expected, within the MTurk sample. However, these results should be interpreted with caution and will need further investigation, as the associations were weak, and no significant correlations were found within the community sample. Given that moral struggles themselves are usually associated with distress (see, e.g., Exline et al. 2014), these results suggest that endorsement of a spiritual jihad mindset may not play a large role in attenuating this overall level of distress. It is important to note that the measures of anxiety and depression used here are not specific to the struggle situation, and instead represent a broader picture of recent mental health symptoms. As such, it makes sense that their associations with the struggle-specific endorsement of the spiritual jihad mindset would be modest in magnitude. In addition, it is of course possible that a person might see a struggle as personally beneficial (i.e., leading to growth) without necessarily experiencing immediate, widespread mood benefits from this mindset. This same logic may also help to explain the (unexpected) lack of conclusive evidence for an association with life satisfaction.

Finally, Muslims who were more likely to endorse a spiritual jihad mindset were found to also endorse greater levels of virtue traits such as gratitude, patience, and forgiveness, as we predicted—but only in the MTurk sample. The lack of associations within the community sample may be a result of devout Muslims portraying themselves with greater humility when inquired about virtues. On the other hand, these Muslims may be more likely to be honest regarding their negative inclinations or be more aware of their lower self-tendencies, potentially due to having very high moral standards. Granted, these are only speculations; these issues can be addressed systematically in future studies with supplementary measures such as implicit or behavioral assessments of virtues or morality.

4.2. Implications for Research and Practice

The proposed psychological construct of spiritual jihad and the associated findings of the present study have noteworthy implications for both research and practice. First and foremost, spiritual jihad is a construct that had never before been studied in the field of psychology. As a result of the current study, researchers can begin to learn more, not only about Islamic spirituality, but also the emerging field of Islamic psychology in a quantifiable manner. The proposed new measure also showed good internal consistency. In addition, by correlating with variables such as Islamic religiousness, daily spiritual experiences, spiritual growth, post-traumatic growth, forgiveness, patience, and gratitude, the measure shows preliminary evidence of validity for future use. Second, although we chose not to use the term jihad within the measure itself, the study may begin to highlight the importance of a more positive and beneficial understanding of the term jihad, a term that can often be misunderstood by non-Muslims and/or Muslims practicing in extremist manners.

Third, the results indicate the importance of considering Muslims’ religious beliefs and practices within therapeutic settings. The practice of spiritual jihad can be brought to attention within the therapeutic setting when working with Muslim clients who may identify themselves as practicing. This may specifically be important for practicing Muslims experiencing struggles related to their religion and spirituality. Fourth, the findings of the study add further evidence that r/s struggles do not necessarily result in only negative psychological outcomes. In circumstances such as those of Muslims who apply a spiritual jihad mindset to their moral struggles, perceived growth may follow. Finally, the results from the current study suggest the possibility of some parallels between Muslims and those of other faith traditions, as many faith traditions are likely to emphasize the idea of seeing moral struggles as a personal challenge that can lead to growth. Further similar constructs may be researched with Christians and other groups residing in the United States (see, e.g., Saritoprak and Exline 2017b). Though Islam may be unique and distinct in certain beliefs and practices, it also shares great overlap with other traditions, specifically Abrahamic traditions, which may open doors for greater cross-cultural research of theory and practice.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to note several limitations of the current study. First, we aimed to develop a self-report measure of a spiritual jihad mindset, in addition to evaluating the newly developed measure’s reliability and validity. Self-report measures have limitations such as susceptibilities to participants responding in biased ways, participants lacking adequate introspective ability to respond accurately, and participants interpreting items in unintended manners. Second, to the best of our knowledge, the construct of spiritual jihad has never been empirically assessed prior to the current study. Hence, the reported findings are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution. Third, the presented data were cross-sectional. Hence, results do not indicate any causal inferences regarding the construct of spiritual jihad. In future research, it will be important to conduct research regarding Muslims and spiritual jihad with longitudinal analyses, and it may be feasible to develop and test experimental interventions.

Fourth, the community sample was local and smaller than intended, which limited the conclusiveness and generalizability of results within the group. In addition, some community sample distributions were less approximately normal, which may have biased hypothesis tests in that sample. Subsequent studies should focus on gathering larger samples from the community, in addition to gathering clinical samples to investigate the role of spiritual jihad among Muslims seeking mental health treatment. Fifth, it is important that future research focuses on more refined and nuanced research predictors and outcomes associated with a spiritual jihad mindset. For example, what factors may mediate or moderate the relationship between Islamic religiousness and having a spiritual jihad mindset?

Additionally, future studies that utilize different research methods such as qualitative analyses and implicit or behavioral measurement can provide further tests of the hypotheses considered here. It is also recommended that researchers translate the Spiritual Jihad Measure into other languages in order to promote greater applicability for non-English speaking Muslims within or outside of the United States. Similarly, it will be important for researchers to modify the measure in regards to its specific terminology that is grounded within an Islamic framework, with the aim of better accommodating other theistic and nontheistic religious orientations. Finally, it will be important for future studies with larger sample sizes to conduct confirmatory factor analyses of the measure.

Author Contributions

S.N.S. designed the study, did the primary data analyses, and served as first author for the introduction, method, results, and discussion sections. J.J.E. gave input on the study design, collected data, and reviewed the manuscript. N.S. also did a majority of data analyses, wrote parts of the method and results sections and gave input on the manuscript draft.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the John Templeton Foundation for funding this research (Grants #36094 and 59916). We would also like to acknowledge Elliott Bazzano, Whitney Bodman, and Zeki Saritoprak for their contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Spiritual Jihad Measure

Think of a type of moral struggle you have experienced or are currently experiencing in life, how did/do you view the struggle you experienced/are experiencing?

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither | Somewhat Agree |

| Agree | Strongly Agree |

The following items are examples of moral struggles:

- I want to do more positive things, however, I’m having trouble doing them (e.g., praying the recommended prayer, tahajjud, and becoming more conscious of Allah)

- I’m struggling with the temptation to do something wrong (e.g., engaging in sexual desires, skipping my prayers, and eating unhealthy)

- I’m feeling guilty because I have done something wrong.

- I’m having trouble telling what is morally wrong and right.

- I have been thinking of my struggle as a test that will make me closer to Allah.

- I have been thinking of my struggle as a desire of my nafs (soul/self) that I must work against.

- I see the struggle as an opportunity to pray and ask Allah for guidance.

- I believe that through this struggle, my iman (faith) will become stronger.

- I have been thinking of my struggle as a trial through which I will become a better Muslim.

- I view the struggle as means of earning more thawāb (good deeds) for the afterlife.

- I know that there is khair (good) in the struggle because there is khair (good) in everything Allah does.

- The struggle is an opportunity for me to seek Allah’s forgiveness.

- I tend to think that the struggle is for my best interest because Allah is al-Alim (all-knowing).

- I believe that the struggle is a way in which I can understand my imperfect human nature.

- I do not see the struggle as part of my spiritual growth (reverse).

- The struggle has no meaning for me (reverse).

- There is no place for Islam in my struggle (reverse).

- I do not view the struggle as means to become closer to Allah (reverse).

- Allah plays no role in my struggle (reverse).

Appendix B. Measure Descriptions

| Measure | Description | Example Item |

| Spiritual Jihad Measure | A 16-item measure to examine the extent to which participants endorse a spiritual jihad interpretive framework in reference to a specific moral struggle. Participants were instructed to rate each item on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) | “I have been thinking of my struggle as a test that will make me closer to Allah” |

| Religious Coping Questionnaire (RCOPE; Pargament et al. 2000) | Abbreviated subscales of the RCOPE were used to measure coping responses to stressful experiences | “Thought the event might bring me closer to God” |

| Psychological Measure of Islamic Religiousness (PMIR; Abu-Raiya et al. 2008) | A measure of Islamic religiousness assessing five dimensions | “I believe in the Day of Judgment” |

| Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Underwood and Teresi 2002) | A 16-item measure assessing spiritual experiences such as a perceived connection with the transcendent | “I feel God’s presence” |

| Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory: Short form (PTGI-S; Calhoun and Tedeschi 1999) | A 13-item measure examining the extent to which individuals perceive themselves as having grown from a reported crisis | “A willingness to express my emotions” |

| Spiritual Transformation Scale (STS; Cole et al. 2008). | A shortened version of the STS assessing perceived spiritual growth and spiritual decline | “In some ways I have shut down spiritually” |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) | A five-item measure of satisfaction with life | “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life” |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder, seven-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006) | A seven-item measure examining frequency of anxiety-related concerns | “Worrying too much about different things” |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Short Form (CES-D-10; Radloff 1977) | A 10-item scale measuring depressive symptoms. | ”I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me” |

| Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form (GQ-6; McCullough et al. 2002) | A six-item scale addressing gratefulness | “I have so much in life to be thankful for” |

| Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS; Thompson and Snyder 2003) | An 18-item self-report questionnaire examining individuals’ general tendency to forgive | “Learning from bad things that I’ve done helps me get over them” |

| 3-Factor Patience Scale (3-FPS, Schnitker 2012) | An 11-item measure of patience | “I am able to wait-out tough times” |

| Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale, 5-item version (MCSDS; Reynolds 1982) | A five-item scale of social desirability | “No matter whom I am talking to, I am always a good listener” |

References

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, Andra Weissberger, and Julie Exline. 2016. An empirical examination of religious/spiritual struggle among Israeli Jews. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, Neal Krause, and Gail Ironson. 2015. Robust links between religious/spiritual struggles, psychological distress, and well-being in a national sample of American adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 85: 565–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, Annette Mahoney, and Catherine Stein. 2008. A psychological measure of Islamic religiousness: Development and evidence for reliability and validity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 18: 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsaruddin, Asma. 2013. Striving in the Path of God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Afsaruddin, Asma. 2007. Striving in the Path of God: Fethullah Gülen’s Views on Jihad. Paper presented as part of the Muslim World in Transition: Contributions of the Gülen Movement conference, London, UK; pp. 494–502. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bayhaqi. 1996. Kitab al-Zuhd al-Kabir (The Book of Great Asceticism). Edited by Amir Ahmad Haydar. Beirut: Muassasat al-Kutub al-Thaqafiyya, vol. 1, p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bukhari. 1990. Al-Sahih. Edited by Mustafa Dayb al-Bugha. Damascus: Dar Ibn Kathir, book 32, hadith 6214. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bursawi. 1990. Ruh al-Bayan. Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, vol 3, p. 424. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazali. 1982. Ihya Ulum-al-Din. Translated by al-Haj Maulana Fazul-ul-Karim. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalil. 1986. Kitab al-‘Ayn. Edited by Mahdi al-Makhzumi and Ibrahim al-Samarai. Beirut: Maktabat al-Hilal, vol. 3, p. 386. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muslim. 2006. Sahih Muslim. Edited by Muhammad Fuad Abd al-Baqi. Istanbul: al-Maktabat al-Islamiyya, Riyadh: Dar Tayba. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zabidi. 1987. Taj al-Arus. Beirut: Darul Hidaye, vol. 27, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, ElSayed M. A. 2015. Reclaiming Jihad: A Qur’anic Critique of Terrorism. Markfield: Kube Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ano, Gene G., and Erin B. Vasconcelles. 2005. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, Michael C., Sampo V. Paunonen, Edward Helmes, and Douglas N. Jackson. 1998. Kin altruism, reciprocal altruism, and the Big Five personality factors. Evolution and Human Behavior 19: 243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, Alexander W., Helen S. Astin, Jennifer A. Lindholm, Alyssa N. Bryant, K. Szelényi, and S. Calderone. 2005. The Spiritual Life of College Students: A National Study of College Students’ Search for Meaning and Purpose. Los Angeles: UCLA Higher Education Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Yoav, and Daniel Yekutieli. 2001. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. The Annals of Statistics 29: 1165–88. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Lawrence G., and Richard G. Tedeschi, eds. 1999. Facilitating Posttraumatic Growth: A Clinician’s Guide. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Brenda S., Clare M. Hopkins, John Tisak, Jennifer L. Steel, and Brian I. Carr. 2008. Assessing spiritual growth and spiritual decline following a diagnosis of cancer: Reliability and validity of the spiritual transformation scale. Psycho-Oncology 17: 112–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, Kathryn M., and Wei Zhang. 2006. Resilience: Determinants, measurement, and treatment responsiveness. CNS Spectrums 11: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, Kavita M. 2006. Predictors of Growth and Decline Following Spiritual Struggles. Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Edward D., Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Jinwoo Lee. 2010. Spiritual struggles and psychological distress: Is there a dark side of religion? Social Indicators Research 98: 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., and Michael E. McCullough. 2003. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Joshua A. Wilt, Nick Stauner, Valencia A. Harriott, and Seyma N. Saritoprak. 2017. Self-Forgiveness and Religious/Spiritual Struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Berlin: Springer, pp. 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Todd W. Hall, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Valencia A. Harriott. 2016. Predictors of growth from spiritual struggle among Christian undergraduates: Religious coping and perceptions of helpful action by God are both important. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 501–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Joshua B. Grubbs, and Ann Marie Yali. 2014. The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 208–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J. 2013. Religious and spiritual struggles. In APA Handbook of Psychology. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 497–75. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., and Eric D. Rose. 2013. Religious and spiritual struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 380–98. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Ann Marie Yali, and William C. Sanderson. 2000. Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 1481–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, Ryan, Michele J. Gelfand, and Monisha Nag. 2010. The road to forgiveness: A meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychological Bulletin 136: 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, Susan. 1997. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine 45: 1207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, John, and Sanford Weisberg. 2011. An {R} Companion to Applied Regression, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage, Available online: http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Freud, Sigmund. 1923/1962. The ego and the id. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2013. Religion, spirituality, and assessment. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, Randy, Bozena Zdaniuk, Richard Schulz, and Michael Scheier. 2009. Positive and negative religious coping and well-being in women with breast cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12: 537–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Vaḥiduddin. 2000. Patience (Sabr). In Principles of Islam. Noida: Goodword, pp. 100–2. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, Manuel, and Werner A. Stahel. 2017. Nonsingular subsampling for regression S~estimators with categorical predictors. Computational Statistics 32: 631–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maechler, Martin, Peter Rousseeuw, Christophe Croux, Valentin Todorov, Andreas Ruckstuhl, Matias Salibian-Barrera, Tobias Verbeke, Manuel Koller, Eduardo L. T. Conceicao, and Maria Anna di Palma. 2018. Robustbase: Basic Robust Statistics R Package Version 0.93-0. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=robustbase (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Martin, Alyce M. 2008. Exploring Forgiveness: The Relationship between Feeling Forgiven by God and Self-forgiveness for a Interpersonal Offense. Doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, John M., and David N. Dixon. 2012. Perceived forgiveness from God and self-forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 31: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, Michael E., Robert A. Emmons, and Jo-Ann Tsang. 2002. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, William R., and Carl E. Thoresen. 2003. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist 58: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizami, Ahmad K. 1997. The Naqshbandiyyah order. In Islamic Spirituality: Manifestations. Edited by Seyyed H. Nasr. New York: Crossroad Publishing, pp. 162–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2007. Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy: Understanding and Addressing the Sacred. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Kavita M. Desai, Kelly M. McConnell, Lawrence G. Calhoun, and Richard G. Tedeschi. 2006. Spirituality: A pathway to posttraumatic growth or decline. In Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice. New York and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa M. Perez. 2000. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 1: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2012. Religious and spiritual aspects of meaning in the context of work life. Psychology of Religion and Workplace Spirituality 1: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., Mohamad A. Brooks, and Jessica Sussman. 2009. Dimensions of religion and spirituality in psychological adjustment in older adults living with congestive heart failure. Faith and Well-Being in Later Life 2009: 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Russell E., and Catherine H. Stein. 2007. God’s will, God’s punishment, or God’s limitations? Religious coping strategies reported by young adults living with serious mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychology 63: 529–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picken, Gavin. 2011. Spiritual Purification in Islam: The Life and Works of al-Muhasibi. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: https://www.R-project.org/Version = 3.4.1 (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Radloff, Lenore S. 1977. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. 2017. Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. Evanston: Northwestern University, Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych Version = 1.7.5 (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Reynolds, William M. 1982. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 38: 119–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]