Abstract

Self-forgiveness is identified as a contributor to psychological wellbeing and may serve as a mechanism through which religiosity supports mental health. There is a dearth of research on wellbeing and the role of self-forgiveness in the English-speaking Caribbean. This preliminary study explored the relationship between religiosity, self-forgiveness, and wellbeing among persons with serious mental illness (SMI), a population largely overlooked in this context. A convenience sample of 362 out-patients receiving care in Trinidad and Tobago completed self-reported measures of self-forgiveness, the Religious Commitment Inventory, and Havard’s Flourishing Measure. Inferential statistics examined group differences in religiosity and wellbeing, and predictive relationships among key variables. Among persons with SMI, higher religiosity was significantly associated with greater wellbeing (p < 0.0001). Additionally, there was greater wellbeing among those who reported a propensity to self-forgive compared to those who did not (p < 0.0001). Self-forgiveness explained a significant part of the relationship between religiosity and wellbeing. Furthermore, among the non-highly religious, self-forgiveness was also significantly associated with greater wellbeing (p < 0.001). Our findings suggest that self-forgiveness may mediate the link between religiosity and wellbeing, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic coping mechanism for individuals with serious mental illness. This study adds to the growing literature on religious coping in mental health and underscores the need for further research to clarify the mediating role of self-forgiveness.

1. Introduction

The interplay between religiosity and wellbeing has garnered significant attention in mental health research. Religiosity, encompassing spiritual beliefs, practices, and a sense of connection to the divine, has been linked to enhanced psychological resilience, reduced psychological distress, and improved quality of life (Koenig 2012; Pargament 2011). However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain underexplored. One promising yet understudied factor is self-forgiveness—a process involving the acknowledgment of personal shortcomings, the release of self-directed negative emotions such as guilt and shame, and the cultivation of self-compassion (Hall and Fincham 2005).

1.1. Religiosity and Wellbeing

Religious commitment, reflecting the degree of religiosity, is the extent to which an individual’s religious beliefs, values, and practices are adhered to and used in day-to-day practice, with the expectation that a highly religious person would demonstrate high levels of such (Alaedein-Zawawi 2015; Worthington et al. 2003). Pargament demonstrated that religious coping can have either positive or negative outcomes; however, individuals generally tend to engage in more positive coping (Pargament et al. 1998).

Previous systematic reviews of the literature and meta-analyses have demonstrated mixed results, but religiosity and religious commitment have been largely associated with positive outcomes with respect to the wellbeing of individuals (Kane 2020; Koenig 2012; Litalien et al. 2022; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2003). Positive belief systems lead to a sense of purpose, optimism, reduced existential angst, and the provision of healthy means to cope with negative life occurrences. These, along with providing social structures and guidelines, promote healthy habits interpersonal relationships, and other adaptive qualities provided by religion. This appears to outweigh the negative complications, such as views of a punitive God, fear of judgement, rigidity in thinking, and the prejudice associated with religion, which generally shift the overall balance toward a more favourable outcome (Khumalo et al. 2023; Koenig 2012; Newman and Graham 2018; Strelan et al. 2009).

Positive effects of religiosity have been associated with life satisfaction, reduction in suicidal thoughts and behaviours, as well as reduction in delinquency, in certain populations investigated in Trinidad and Tobago (Habib et al. 2018; Mustapha 2013; Toussaint et al. 2008). Religious commitment has been described as a significant resource contributing to flourishing among Afro-Trinidadians (Skalski-Bednarz 2024).

1.2. Forgiveness and Wellbeing

1.2.1. Defining Forgiveness

While there has not been a consensus among philosophers and researchers as to what forgiveness is, it is generally agreed that it is a multi-faceted process (Worthington 2005; Mendes-Teixeira and Duarte 2021; Tucker et al. 2015). Commonly agreed upon elements include forgiveness being a process of change within an individual who has been transgressed (Worthington 2005). It is a diminishing of negative experiences, possibly combined with a concurrent increase in positive experiences toward the transgressor, following an offence (Ashton et al. 1998; Fincham et al. 2004; Worthington 2005). These experiences may be classed as affective, where there is a reduction in negative emotions, which may then be substituted for neutral and ultimately positive emotions; cognitive, where the individual may no longer desire revenge or blame the transgressor, setting aside the negative emotions they have a right to; and behavioural, where the offended party ceases to act in a vengeful manner (Enright et al. 1991; North 1987). Interpersonal forgiveness occurs between two individuals, and self-forgiveness is directed at one’s own moral failings, relieving oneself from self-condemnation, and does not involve an external party (Enright et al. 1991; Vismaya et al. 2024) State forgiveness involves the act of forgiving an offender, while trait forgiveness is the disposition to forgive (Lee and Enright 2019).

1.2.2. Conceptualization of Forgiveness in Religion

Religion is an important component of the multicultural fabric of the society of Trinidad and Tobago, with individuals being influenced by various religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam (Forde 2024). It is a core component of Christianity, involving divine forgiveness of humans by God, essential acceptance of such, and commands to extend that to others (Khosla et al. 2020; Plante and Sherman 2001). In Islam, Allah dispenses justice and is forgiving; repenting, and asking Allah for forgiveness is virtuous; and in Hinduism, karma indicates that justice will eventually occur, if not in the current lifetime, in a future one. The application of benevolence and forgiveness is crucial in fulfilling their karma (Khosla et al. 2020; Plante and Sherman 2001).

1.3. Self-Forgiveness and Wellbeing

The positive impact of self-forgiveness on wellbeing has been well supported by empirical evidence spanning physical, social, and most notably, psychological health domains (Cornish and Wade 2015b; Davis et al. 2015; Skalski-Bednarz 2024). Both the perception and experience of having been forgiven by a benevolent God, together with therapeutic measures targeting self-forgiveness, have been linked to the strengthening of one’s mental wellbeing (Cornish and Wade 2015b; Skalski-Bednarz 2024).

1.4. Self-Forgiveness, Guilt, and Shame in Individuals with Serious Mental Illness

Guilt and shame and their relationship to self-forgiveness remain underexplored, and available evidence is mixed. Although guilt and shame have been noted to have negative consequences for mental health, guilt has been recognized as potentially adaptable when characterized as making oneself culpable for one’s actions, thus creating the opportunity for addressing erroneous and negative behaviour. Shame, however, involves directing the fault at oneself, potentially leading to a negative view of self and worthlessness (Carpenter et al. 2019; McGaffin et al. 2013). This is supported by the tendency toward guilt having a positive association with self-forgiveness, while shame has the inverse. Success in the therapeutic process of individuals with alcohol and other substance use disorders has highlighted the potential benefit of self-forgiveness in treating these conditions, by taking advantage of the benefits of positive and adaptive guilt while minimizing the harmful impact of shame (Carpenter et al. 2019; McGaffin et al. 2013).

Other established therapeutic benefits of self-forgiveness include decreasing long-standing dysfunctional guilt, shame, and self-condemnation associated with hypersexuality in individuals who viewed guilt and shame in a maladaptive context; reducing co-occurring depressive symptoms; and strengthening resolve to confront and decrease such self-destructive behaviour (Mosher et al. 2017). Self-forgiveness has even been proposed for the therapeutic benefit of reducing non-suicidal self-injury and suicide risk, and may do so by addressing the cognitive maladaptations that may result in such behaviours, inclusive of negative usage of guilt and feelings of shame (Hirsch et al. 2017). The harmful effects of self-condemnation which could present as maladaptive forms of guilt and shame have been reduced by self-forgiveness; thereby constituting a crucial component in addiction recovery, reducing suicidality, enhancing adaptive coping, and improving overall physical and mental wellbeing (Toussaint et al. 2023; Webb and Boye 2024).

1.5. Justification of the Study

There is very limited research on religious commitment and wellbeing and the role of forgiveness or self-forgiveness in the English-speaking Caribbean. To date, very few studies in the Caribbean or worldwide have investigated this relationship among persons with serious mental illness. While several research papers have been published on self-forgiveness as a promising therapeutic intervention to promote mental wellbeing, there is a paucity of similar studies in this region. This research is therefore both novel and significant and seeks to highlight the need for further investigation into self-forgiveness as a tool to assist the mental wellbeing of the people of the Caribbean and worldwide.

1.6. Conceptual Framework

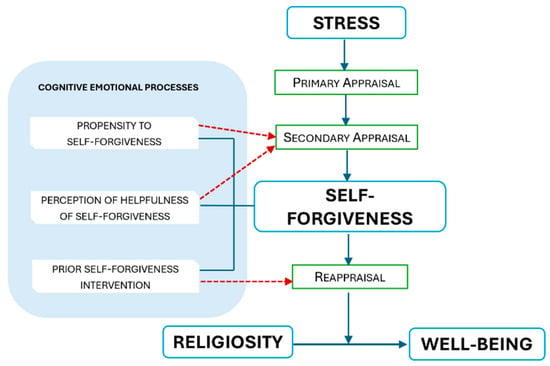

Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model of stress and coping is commonly adopted as a useful framework when exploring the relationship between forgiveness and wellbeing (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The model considers emotional responses to stress as resulting from a primary cognitive appraisal of the severity of threat posed by the stressor, and secondary appraisal and reappraisal of the coping resources available to deal with the threat. Using this framework, Worthington and Scherer posited that forgiveness might be an emotion-focused coping mechanism (Worthington and Scherer 2004). Toussaint et al. expanded this position and explained the mechanism by which self-forgiveness might enhance wellbeing (Toussaint et al. 2017). They suggested that this process reduces the stress of self-condemnation caused by personal failures, guilt, and shame, and enhances wellbeing through the mediation and moderation of negative self-directed emotions. We believe that the ability to self-forgive would be fundamental to wellness among persons with serious mental illness and could be determined by assessing their propensity to forgive themselves if they did something wrong.

In the population of persons with serious mental illness, there is a high prevalence of self-directed internal stressors like guilt, shame, anger, and regret (Hirsch et al. 2017; Luoma et al. 2013). In the primary appraisal phase of Lazarus and Folkman’s model, persons with serious mental illness may appraise their past life experiences as an ongoing psychological threat, creating persistent stress even in the absence of external danger. Religio-cultural norms and other expectancies significantly shape one’s ability to forgive oneself. Woodyatt et al., for example, speak of the internal narrative of shame, which makes it more difficult to engage in successful self-forgiveness (Woodyatt et al. 2017). We therefore considered a positive appraisal of self-forgiveness, reflected as a personal conviction that self-forgiveness will be helpful to mental health, as an important concept that is likely to contribute to wellbeing. The perception that self-forgiveness is helpful can shift the secondary appraisal of coping resources, allowing persons to reframe the internal threat as an opportunity for resolution and personal growth. This may result in a reduction in the perceived severity of the stress and improved wellness. Removal of barriers to self-forgiveness can also become a therapeutic focus if it is shown that believing in its efficacy can contribute significantly to wellbeing.

The prior use of self-forgiveness in therapy may similarly enhance the secondary appraisal process by providing a learned coping strategy specifically suited to self-directed emotional pain. Persons in treatment who have successfully practiced self-forgiveness may perceive themselves as more capable of handling feelings of guilt or shame, thus improving their coping resilience and self-efficacy. Over time, repeated use of self-forgiveness as a coping strategy can result in it becoming an internalized resource for psychological distress associated with self-condemnation. For our study, capturing this aspect of prior self-forgiveness was considered a potentially important element in determining its relationship with mental wellbeing. In addition to the propensity to self-forgive, integrating the perception and prior use of self-forgiveness into the stress and coping model may therefore provide a meaningful extension, particularly for persons with serious mental illness. We would expect that among persons with serious mental illness, those with a more self-forgiving disposition are likely to experience greater wellbeing. Also, self-forgiveness is more likely to promote wellbeing when individuals perceive it as a useful coping strategy or have previously engaged in it intentionally. These cognitive-emotional processes are expected to enhance the emotional benefits of self-forgiveness as a coping mechanism, especially when it aligns with the individual’s beliefs and coping history.

If utilized as a therapeutic intervention, persons with serious mental illness may be taught to release self-condemnation and experience improved wellbeing. It may also create an opportunity for self-forgiveness to be implemented outside of a religious context, making it suitable for both religious and non-religious persons (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed exploration of the role of self-forgiveness in the relationship between religiosity and wellbeing using the stress and coping model.

1.7. Objectives of the Study

Based on the conceptual framework, we hypothesized that self-forgiveness plays a role in the relationship between religiosity and wellbeing among persons with serious mental illness. This study, therefore, investigated the following:

- The association between demographics and high religiosity among persons with serious mental illness.

- The relationship between religiosity and wellbeing among persons with serious mental illness.

- Whether cognitive-emotional processes related to self-forgiveness will enhance the emotional benefits of self-forgiveness as a coping mechanism, among both religious and non-religious persons, viz.,

- Propensity to self-forgive;

- Perception of helpfulness of self-forgiveness;

- Prior self-forgiveness intervention.

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents key demographic characteristics of 349 respondents diagnosed with serious mental illness (SMI) seeking mental health services. More than half were female (68.8%) and single (56%), over a third were within the 26–40 years age range (33.5%), while 42.4% self-identified as being of mixed descent. Almost all the respondents identified with a religion (99.7%), with Christianity being the most common (65.5%).

Table 1.

Demographics of participants with serious mental health illness, Trinidad (n = 349).

2.2. Religiosity and Wellbeing

Religious Commitment Inventory (RCI) score ranged from 10 to 50 (mean 29.3 (SD = 11.6)) and the Harvard Flourishing Measure of Wellbeing ranged from 17 to 120 (Mean 71.4 (SD = 20.6)).

Among the respondents, 21% were considered highly religious (RCI scores ≥ 41). The type of religion was significantly associated with religiosity (p = 0.003). Among the highly religious group, 80.8% identified with the Christian religion compared to 61.8% in the not highly religious group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between demographics and religiosity among persons with SMI, Trinidad.

There was a significant mean difference in wellbeing scores for age group, religiosity, and self-forgiveness (p < 0.001, respectively). Respondents with high religiosity had a significantly higher mean wellbeing score compared to those with low religiosity (83.1 ± 20.2 vs. 68.3 ± 19.6, p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean differences in wellbeing scores by selected characteristics of persons with SMI, Trinidad.

2.3. Correlational Analyses

2.3.1. Self-Forgiveness and Religiosity

There was a significant association between religiosity and the propensity for self-forgiveness (p = 0.003).

2.3.2. Self-Forgiveness and Wellbeing

Among the sample, 62.8% of persons reported a propensity towards self-forgiveness, and there was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.0001) in the mean wellbeing scores for those who had a propensity to self-forgiveness (77.4 ± 19.3) versus those who did not (61.8 ± 19.0).

Most persons (80.8%) perceived that self-forgiveness would help their mental health, while 16.3% felt it would harm or have no effect on their mental health (n = 349). Persons who perceived that self-forgiveness would benefit their mental health had significantly higher wellbeing scores compared to those who did not (73.8 ± 20.3 vs. 60.0 ± 19.0, p < 0.0001).

Approximately two-thirds (63.3%) of respondents believed that prior experience with self-forgiveness positively influenced their mental health. The average wellbeing score for this group was significantly higher at 75.9 ± 1.2, compared to 66.6 ± 2.1 for those who did not share this belief (p < 0.001).

2.4. Hierarchical Regression Analyses

2.4.1. Relationship Between Religiosity, Self-Forgiveness, and Wellbeing–Entire Sample (Table 4)

In Model 1, the inclusion of religiosity explained 8.6% of the variance in wellbeing scores, where those who were not highly religious had lower wellbeing scores (β = −14.83, p < 0.01). In Model 2, when the propensity to self-forgive was added, there was a significantly improved model fit with 18.5% of the variance explained (a 115% increase in explained variance) for a predicted increase in wellbeing score (β = −11.47, p < 0.01). Marginal increases in wellbeing score were predicted when variables that measured respondents’ perception of self-forgiveness as helpful to their mental health (β = −11.12, p < 0.01) and prior helpfulness of self-forgiveness (β = −10.85, p < 0.01) were added as predictors (see Models 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression models of relationship between religiosity, self-forgiveness, and wellbeing (entire sample).

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression models of relationship between religiosity, self-forgiveness, and wellbeing (entire sample).

| Factors | Wellbeing Score * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| β | β | β | β | |

| Religiosity | ||||

| (Not religious vs. highly religious) | −14.83 *** | −11.47 *** | −11.12 *** | −10.85 *** |

| (2.595) | (2.508) | (2.520) | (2.562) | |

| Propensity to self-forgive | ||||

| (No vs. Yes) | −14.05 *** | −12.22 *** | −11.16 *** | |

| (2.123) | (2.237) | (2.405) | ||

| Perception of self-forgiveness as helpful for mental health | ||||

| (Harm vs. Help) | −6.347 ** | −5.895 ** | ||

| (2.902) | (2.953) | |||

| Prior helpfulness of self-forgiveness | ||||

| (No vs. Yes) | −3.654 | |||

| (2.423) | ||||

| Constant | 83.10 *** | 85.85 *** | 85.87 *** | 86.58 *** |

| (2.308) | (2.247) | (2.257) | (2.284) | |

| Observations | 349 | 339 | 335 | 330 |

| R-squared | 0.086 | 0.185 | 0.192 | 0.203 |

| % Change in R-squared | +115.1% | +3.8% | 5.7% | |

| Adj (R2) | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 |

| F Test | 20.69 | 20.69 | 20.69 | 20.69 |

* Wellbeing score based on Harvard Flourishing Scale; Standard errors in parentheses *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05.

2.4.2. Sub-Group Analysis—Relationship Between Self-Forgiveness and Wellbeing Among Those Not Highly Religious

A hierarchical regression was conducted in Table 5 to examine the relationship between self-forgiveness and wellbeing. In Model 1, propensity for self-forgiveness was significantly associated with higher wellbeing scores (β = 13.90, p < 0.001), accounting for 12.1% of the variance. In Model 2, the inclusion of perception of self-forgiveness as helpful to mental health (β = 5.98, p > 0.05) improved the model fit slightly (0.7% increase), though not statistically significant. The further addition of prior self-forgiveness (β = 4.60, p > 0.05) in Model 3 was not statistically significant, but the model’s explained variance increased by 1.3% to a total R2 of 14.1%. However, the coefficient for propensity to self-forgive remained significant, albeit attenuated (Model 2: β = 12.00, p < 0.001; Model 3: β = 10.54, p < 0.001) across all models.

Table 5.

Hierarchical regression models of relationship between self-forgiveness and wellbeing among those not highly religious (sub-group).

3. Discussion

The literature is replete with support for the relationship between religiosity and wellbeing in general and in various clinical populations (Kane 2020; Litalien et al. 2022; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2003). There has been little exploration of this relationship, and the possible therapeutic application of religious coping to promote wellness in persons with serious mental illness. This study explored the association between religiosity and wellbeing among persons with serious mental illness in treatment, and whether self-forgiveness might explain any association.

In this study, conducted in a multicultural society, twenty-one percent (21%) of persons with serious mental illness were highly religious. An over-representation of persons of the Christian faith in the sample might explain the significant association between this religious group and being highly religious. Consistent with reports among other populations, religiosity was found to be associated with greater wellbeing among persons with serious mental illness (Kane 2020; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006). Individuals who were not highly religious reported significantly lower wellbeing scores, supporting the well-documented association between religiosity and positive mental health outcomes in this population. Prior reports have attributed the association as potentially due to increased social support, moral coherence, and coping mechanisms available through religious frameworks (Aggarwal et al. 2023).

In many populations, forgiveness has been cited as a possible mechanism through which this association occurs (Akhtar et al. 2017; Alaedein-Zawawi 2015; Kane 2020; Lawler-Row 2010). The dimension of self-forgiveness has been associated with psychological wellbeing for clients who have hurt others and acknowledge objective wrongdoing, often with shame and guilt (Cornish and Wade 2015b; Enright 1996; Fisher and Exline 2010). Individuals with serious mental illness often report negative self-evaluations, internalized stigma, and disproportionate feelings of shame and guilt that do not derive just from obvious wrongdoing (Hirsch et al. 2017; Luoma et al. 2013). The self-condemnation is often rooted in early experiences of being abused, invalidated or neglected. Matos et al. (2013) and others (Gilbert 2009) have found that early emotional abuse is linked to shame and self-criticism, which in turn are linked to depression and anxiety (Matos et al. 2013; Gilbert 2009). Gilbert’s compassion-focused theory posits that people with early trauma develop a strong “inner critic” leading to shame and self-attacking behaviour, and they are often unable to reconcile negative self-beliefs with an idealized self-image.

It is no surprise, therefore, that in this study, those with the propensity to self-forgive had markedly higher wellbeing scores than those who did not report such a self-forgiving trait, and self-forgiveness was significant in explaining the relationship between religiosity and wellbeing. The findings suggest that self-forgiveness can be effective in addressing the guilt, shame, and self-condemnation that are commonly experienced by persons with serious mental illness, by harnessing the positive effects of high religiosity to improve wellbeing.

Incorporating self-forgiveness, its perception and prior use into the stress and coping model resulted in a marginal increase in wellbeing among persons with higher religiosity compared to those with lower religiosity scores. Religious traditions often emphasize forgiveness, both of others and oneself, and religious individuals may internalize self-forgiveness as a value or practice that contributes to psychological resilience. Further work can clarify the mediating effect of self-forgiveness as an explanation for how religiosity confers benefits to wellbeing among religious persons with serious mental illness.

This study demonstrated that even among those with lower religiosity, it was significant that persons with SMI who were more likely to forgive themselves were found to have higher levels of wellbeing. The findings therefore support the growing recognition of self-forgiveness as a useful intervention and suggest its usefulness to improve wellbeing among all persons with serious mental illness. Therapeutic interventions that foster self-forgiveness may support wellbeing, especially in secular or religiously diverse therapeutic contexts.

Prior randomized controlled trials have documented that self-forgiveness can be effectively taught to individuals experiencing self-condemnation (Cornish and Wade 2015a; Griffin et al. 2015; Vismaya et al. 2024), including those with psychiatric disorders (Peterson et al. 2017), making this a potentially effective psychological intervention that can be incorporated into the management of psychiatric disorders (Griffin et al. 2015; Vismaya et al. 2024; Peterson et al. 2017). Mental health professionals should become aware of the potential usefulness of religious coping and be prepared to assess individual spiritual needs, and include forgiveness interventions in mental health treatment plans, to reduce psychological distress and enhance psychological wellbeing, regardless of spiritual orientation.

Overall, this study underscores the potential value of self-forgiveness as a therapeutic intervention among persons with serious mental illness. However, these findings derive from a very preliminary exploration. Future work should employ formal mediation analyses and explore possible moderators. The cross-sectional design and the absence of formal valid measures also limit the present study. Longitudinal studies would help clarify causality and directionality. The extent and nature of self-condemnation among persons with serious mental illness, its relationship with psychological wellbeing, and the impact and mechanism of self-condemnation on wellbeing, also need to be firmly established among this clinical population. Further research will guide the development of a self-forgiveness intervention best suited to dealing with the self-condemnation experienced by persons with serious mental illness.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study utilized a convenience sample of 362 adult patients with diagnosed serious mental illness seeking mental health services in Trinidad. Participants were recruited from private and public out-patient psychiatric clinics over a 3-month period, June to August 2024. The study recruited only persons who were already engaged in a mental health intervention but were not at the stage of therapy where the content of the questionnaire might negatively impact the therapeutic process.

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Religious Commitment Inventory-10 (RCI-10)

The RCI-10 (Worthington et al. 2003) was used to measure participants’ levels of religious commitment. This self-report instrument comprises 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true of me) to 5 (Totally true of me). The inventory evaluates two dimensions:

Intrapersonal Religious Commitment: Reflecting the internalization of religious beliefs and their significance in the individual’s personal life.

Interpersonal Religious Commitment: Reflecting the outward expression of religious beliefs through behaviours and interactions.

The RCI-10 has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.90) and robust validity across diverse populations. Scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating stronger religious commitment. In this study, the RCI-10 was used to quantify religiosity as an independent variable. An RCI score greater than one SD higher than the mean is considered highly religious (Worthington et al. 2003).

4.2.2. Harvard Flourishing Measure

The Harvard Flourishing Measure was used to assess participants’ overall wellbeing and life satisfaction. This instrument consists of 10 items that capture multiple domains of human flourishing, including physical and mental health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, social relationships, and financial and material stability. Responses are rated on a 10-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater flourishing in each domain. The Cronbach’s alpha for the Harvard Flourishing Measure is 0.89.

The Harvard Flourishing Measure has demonstrated strong reliability and validity in diverse populations and provides a comprehensive measure of wellbeing that aligns with the multidimensional nature of flourishing. For this study, the Harvard Flourishing Measure served as a dependent variable to explore its relationship with religious commitment and other factors.

4.2.3. Self-Forgiveness

A de novo questionnaire collected demographic information on sex, age, nationality, ethnicity, highest education level, marital status, employment status, and religion. The questionnaire also collected data on the respondent’s perception of and experience with forgiving others and self-forgiveness and beliefs about the effect of forgiveness on mental health.

Three questions were used to measure various cognitive-emotional dimensions of self-forgiveness. Responses were coded into dichotomous variables which served as potential mediators of the relationship between religious commitment and wellbeing. Responses were coded as 0 (No) and 1 (Yes) for analysis.

- Do you forgive yourself if you do something wrong? This was considered a proxy measure for the self-forgiveness trait, described as the propensity to self-forgive.

- How do you think forgiving will affect your mental health if you forgive yourself? Respondents who perceived self-forgiveness as helpful to mental health on a 5-point Likert scale were coded as Yes. Those who perceived self-forgiveness as having no effect or as harmful were coded as No.

- Do you think that forgiveness is already playing/has played a role in improving your mental health? Respondents self-reporting prior benefit from self-forgiveness were coded as Yes.

4.3. Procedure

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine and the North Central Regional Health Authority. Questionnaires were put into the Research Electronic Data Capture software (REDCap) and accessed through an online link. The questionnaires were administered by trained research assistants who, after obtaining informed consent, ensured that questions were clearly understood and answered. Participation was voluntary, and all data were collected anonymously.

4.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were generated to summarize the demographic characteristics of the study population and the primary variables of interest. To evaluate associations between the dependent variable (wellbeing score) and key independent variables (religiosity, religion, sex, and age group), independent sample t-tests and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted. When religiosity was treated as a categorical variable, Chi-squared tests were used to assess the associations. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were subsequently performed to assess for incremental changes in wellbeing scores by the inclusion of self-forgiveness measures in the model.

Additional analyses were conducted within the subgroup classified as non-religious to determine whether the observed associations held consistently across this specific population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.R.; methodology, S.D.R.; validation, S.D.R., S.-A.H., M.J., M.I.; formal analysis, S.-A.H. and M.I.; investigation, M.J.; resources, S.D.R., S.-A.H., M.J.; data curation, S.-A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.R., S.-A.H., M.J.; writing—review and editing, S.D.R., S.-A.H., M.J., M.I.; supervision, S.D.R.; project administration, S.D.R.; funding acquisition, S.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Campus Research and Publication Fund Committee of the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, grant number CRP.3.MAR24.05.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine (CREC-SA.2546/02/2024, 29 February 2024), and the Ethics Committee of the North Central Regional Health Authority (29 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.D.R. These data are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality of research participants and prevent any potential compromise of their privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aggarwal, Shilpa, Judith Wright, Amy Morgan, George Patton, and Nicola Reavley. 2023. Religiosity and Spirituality in the Prevention and Management of Depression and Anxiety in Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23: 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Sadaf, Alan Dolan, and Jane Barlow. 2017. Understanding the Relationship Between State Forgiveness and Psychological Wellbeing: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 450–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaedein-Zawawi, Jehad. 2015. Religious commitment and psychological well-being: Forgiveness as a mediator. European Scientific Journal ESJ 11: 117–41. Available online: https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/5180 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Ashton, Michael C., Sampo V. Paunonen, Edward Helmes, and Douglas N. Jackson. 1998. Kin Altruism, Reciprocal Altruism, and the Big Five Personality Factors. Evolution and Human Behavior 19: 243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Thomas P., Naomi Isenberg, and Jaime McDonald. 2019. The Mediating Roles of Guilt- and Shame-Proneness in Predicting Self-Forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences 145: 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, Marilyn A., and Nathaniel G. Wade. 2015a. A Therapeutic Model of Self-Forgiveness with Intervention Strategies for Counselors. Journal of Counseling Development 93: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, Marilyn A., and Nathaniel G Wade. 2015b. Working through Past Wrongdoing: Examination of a Self-Forgiveness Counseling Intervention. Journal of Counseling Psychology 62: 521–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Don E., Man Yee Ho, Brandon J. Griffin, Chris Bell, Joshua N. Hook, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Cirleen DeBlaere, Everett L. Worthington, and Charles J. Westbrook. 2015. Forgiving the Self and Physical and Mental Health Correlates: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Counseling Psychology 62: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, Robert D. 1996. Counseling Within the Forgiveness Triad: On Forgiving, Receiving Forgiveness, and Self-Forgiveness. Counseling and Values 40: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, Robert, Radhi al-mabuk, Pamela Conroy, David Eastin, Suzanne Freedman, Sandra Golden, John Hebl, Tina Huang, Younghee Park, Kim Pierce, and et al. 1991. The Moral Development of Forgiveness. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 123–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, Frank D., Steven R. H. Beach, and Joanne Davila. 2004. Forgiveness and Conflict Resolution in Marriage. Journal of Family Psychology 18: 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Mickie L., and Julie J. Exline. 2010. Moving Toward Self-Forgiveness: Removing Barriers Related to Shame, Guilt, and Regret. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 548–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, Maarit. 2024. Religions in Trinidad and Tobago. In The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Religions, Oxford Handbooks. Edited by Michelle Gonzalez Maldonado. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Paul. 2009. The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Brandon J., Everett L. Worthington, Caroline R. Lavelock, Chelsea L. Greer, Yin Lin, Don E. Davis, and Joshua N. Hook. 2015. Efficacy of a Self-Forgiveness Workbook: A Randomized Controlled Trial with Interpersonal Offenders. Journal of Counseling Psychology 62: 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, Dianne Gabriela, Casswina Donald, and Gerard Hutchinson. 2018. Religion and Life Satisfaction: A Correlational Study of Undergraduate Students in Trinidad. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1567–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, Julie H., and Frank D. Fincham. 2005. Self-Forgiveness: The Stepchild of Forgiveness Research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 24: 621–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Jameson K., Jon R. Webb, and Loren L. Toussaint. 2017. Self-Forgiveness, Self-Harm, and Suicidal Behavior: Understanding the Role of Forgiving the Self in the Act of Hurting One’s Self. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Jr., Everett L. Worthington, Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Davis Kealanohea. 2020. Forgiveness and Gratitude as Mediators of Religious Commitment and Well-Being Among Polynesian Americans. Ph.D. dissertation, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA. Available online: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/9059 (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Khosla, Meetu, Selene Khosla, and Irene Khosla. 2020. Does Religious Commitment Facilitate Forgiveness? A Study on Indian Young Adults. The International Journal of Indian Psychology 8: 1020–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, Itumeleng P., Sahaya G. Selvam, and Angelina Wilson Fadiji. 2023. The Well-Being Correlates of Religious Commitment amongst South African and Kenyan Students. South African Journal of Psychology 53: 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. International Scholarly Research Notices 2012: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler-Row, Kathleen A. 2010. Forgiveness as a Mediator of the Religiosity—Health Relationship. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yu-Rim, and Robert Enright. 2019. A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Forgiveness of Others and Physical Health. Psychology Health 34: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litalien, Manuel, Dominic Odwa Atari, and Ikemdinachi Obasi. 2022. The Influence of Religiosity and Spirituality on Health in Canada: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 373–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, Jason B., Richard H. Nobles, Chad E. Drake, Steven C. Hayes, Alyssa O’Hair, Lindsay Fletcher, and Barbara S. Kohlenberg. 2013. Self-Stigma in Substance Abuse: Development of a New Measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 35: 223–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, Marcela, José Pinto-Gouveia, and Cristiana Duarte. 2013. Internalizing Early Memories of Shame and Lack of Safeness and Warmth: The Mediating Role of Shame on Depression. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 41: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaffin, Breanna J., Geoffrey C. B. Lyons, and Frank P. Deane. 2013. Self-Forgiveness, Shame, and Guilt in Recovery from Drug and Alcohol Problems. Substance Abuse 34: 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Teixeira, Ana Isabel, and Cidália Duarte. 2021. Forgiveness and Marital Satisfaction: A Systematic Review. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão 41: e200730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, Francisco Lotufo Neto, and Harold G. Koenig. 2006. Religiousness and Mental Health: A Review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 28: 242–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, David K., Joshua N. Hook, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2017. Self-Forgiveness and Hypersexual Behavior. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Cham: Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature, pp. 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, N. 2013. Religion and Delinquency in Trinidad and Tobago. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Religion-and-Delinquency-in-Trinidad-and-Tobago-Mustapha/f6444be2b597d70ca30c6af434bb1e75bec9d877 (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Newman, David B., and Jesse Graham. 2018. Religion and Well-Being. In Handbook of Well-Being. Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Newman-9/publication/322702283_Religion_and_Well-being/links/5a6a5a270f7e9b1c12d18335/Religion-and-Well-being.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- North, Joanna. 1987. Wrongdoing and Forgiveness. Philosophy 62: 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2011. Religion and Coping: The Current State of Knowledge. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Oxford Library of Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 269–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of Positive and Negative Religious Coping with Major Life Stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Sarah J., Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Stephanie D. Womack, Joshua N. Hook, Don E. Davis, and Brandon J. Griffin. 2017. The Benefits of Self-Forgiveness on Mental Health: Evidence from Correlational and Experimental Research. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, Thomas G., and Allen C. Sherman. 2001. Faith and Health: Psychological Perspectives. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skalski-Bednarz, Sebastian Binyamin. 2024. The Interplay of Forgiveness by God and Self-Forgiveness: A Longitudinal Study of Moderating Effects on Stress Overload in a Religious Canadian Sample. BMC Psychology 12: 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychological Bulletin 129: 614–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, Peter, Collin Acton, and Kent Patrick. 2009. Disappointment With God and Well-Being: The Mediating Influence of Relationship Quality and Dispositional Forgiveness. Counseling and Values 53: 202–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren, Everett L. Worthington, Jon R. Webb, Colwick Wilson, and David R. Williams. 2023. Forgiveness in Human Flourishing. In Human Flourishing: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Neuroscience, Health, Organizations and Arts. Edited by Mireia Las Heras, Marc Grau Grau and Yasin Rofcanin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren L., David R. Williams, Marc A. Musick, and Susan A. Everson-Rose. 2008. The Association of Forgiveness and 12-Month Prevalence of Major Depressive Episode: Gender Differences in a Probability Sample of U.S. Adults. Mental Health, Religion Culture 11: 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren L., Jon R. Webb, and Jameson K. Hirsch. 2017. Self-Forgiveness and Health: A Stress-and-Coping Model. In Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Edited by Lydia Woodyatt, Jr., Everett L. Worthington, Michael Wenzel and Brandon J. Griffin. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Jeritt R., Rachel L. Bitman, Nathaniel G. Wade, and Marilyn A. Cornish. 2015. Defining Forgiveness: Historical Roots, Contemporary Research, and Key Considerations for Health Outcomes. In Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health. Edited by Loren Toussaint, Everett Worthington and David R. Williams. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismaya, A., Aswathy Gopi, John Romate, and Eslavath Rajkumar. 2024. Psychological Interventions to Promote Self-Forgiveness: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychology 12: 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, Jon R., and Comfort M Boye. 2024. Self-Forgiveness and Self-Condemnation in the Context of Addictive Behavior and Suicidal Behavior. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation 15: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodyatt, Lydia, Everett L. Worthington, Michael Wenzel, and Brandon J. Griffin, eds. 2017. Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness, 1st ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, Everett L., ed. 2005. Handbook of Forgiveness. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, Everett L., and Michael Scherer. 2004. Forgiveness Is an Emotion-Focused Coping Strategy That Can Reduce Health Risks and Promote Health Resilience: Theory, Review, and Hypotheses. Psychology Health 19: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr., Nathaniel G. Wade, Terry L. Hight, Jennifer S. Ripley, Michael E. McCullough, Jack W. Berry, Michelle M. Schmitt, James T. Berry, Kevin H. Bursley, and Lynn O’Connor. 2003. The Religious Commitment Inventory—10: Development, Refinement, and Validation of a Brief Scale for Research and Counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology 50: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).