1. Introduction

In a shuttered Prague apartment, Jacques Austerlitz—the central character in W.G. Sebald’s 2001 novel by the same name—strains to recall the Czech word for squirrel. The answer (

veverka) ultimately comes to him, but this act of translation stirs up more questions than it resolves. Reminiscing on his childhood habit of watching the squirrels bury and exhume acorns in Prague’s public gardens with his nanny, Austerlitz muses: “How indeed do the squirrels know, what do we know ourselves, how do we remember and what is it we find in the end?” (

Sebald 2001, p. 204).

These questions form the core around which Sebald’s final novel orbits. The story follows Austerlitz, a middle-aged art historian living in England, on his elliptical attempts to uncover a past submerged by the rubble of WWII and the genocide of European Jews. The novel is written in the first-person and begins with the unnamed, Sebald-like narrator describing his travels from England to Belgium in the 1960s.

1 On one of these trips, the narrator meets Austerlitz in an Antwerp train station and the two strike up a conversation. Over the next thirty years, the pair become friends, fall out of touch, and reconnect after Austerlitz suffers a nervous breakdown.

The text’s narrative structure is nested and labyrinthine; it speaks to the impossibilities of memory even as it is obsessed with its possibilities. The narrator recounts Austerlitz’s life story: His escape from Prague via Kindertransport to Wales, his teenage shock at the discovery that the Calvinist minister and sickly woman he grew up with are not his biological parents, his academic obsession with public architecture and, in middle age, his attempt to hunt for the traces of his Jewish parents before their disappearance into the German camps. Throughout the novel, Austerlitz suffers from sudden onrushes of memory, what James Wood describes in his introduction as “visionary experience[s].” These visions grant access to otherwise invisible histories. They also situate Austerlitz as a modernized mystic pilgrim as he follows a trail of partially submerged memories to Prague, the city of his birth. In Prague, he discovers his former nanny, Vera Ryšanová, and learns that both of his parents—Agáta Austerlitz and Maximilian Aychenwald—were interned in Nazi concentration camps.

While Austerlitz dictates the focus of the narrative, the novel is a mélange of material. Sebald weaves together Austerlitz’s biography, the narrator’s thoughts and experiences and wide-ranging, eclectic musings on history, architecture, art and philosophy. This eclectic approach includes images—photographs, maps and blueprints—which are scattered throughout the text. The provenance of these images and their connection to the plot are sometimes vague and associative but were all carefully chosen by the author. Sebald was himself a photographer and he also worked with the photographer Michael Brandon-Jones for his publications (

Sebald 2023).

Many of the photographs in the text are found images or were manipulated in other ways. In her discussion of the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery’s exhibition of Sebald’s archival materials and photographs, Anna McNay explains that “[f]requently Sebald or Brandon-Jones would rephotograph a photograph—as well as objects and works of art—occasionally manipulating them on a photocopier and rendering them almost uncanny” (

McNay 2019). In

Austerlitz, these images are diegetic; the narrator mentions that Austerlitz gave him his collection of “hundreds of pictures”, which are folded into his retelling. At the same time, the images included in the text are uncaptioned and frequently only indirectly addressed by the narrative.

Through both form and content, Austerlitz experiments with how the Holocaust and other acts of violence are remembered and contextualized. Austerlitz’s recollection of the Czech word veverka foreground both the process (“how do we remember?”) and the object (“what is it we find in the end?”) of memory. In answer to these questions, Sebald wrestles with a new memorial crisis brought about by the dwindling number of Holocaust survivors and first-person accounts of the violence of World War II.

Facing this crisis, Sebald engages in a heritage of Jewish mystical thought predating the Holocaust. This extends a project that others have already begun. James R. Martin, for example, identifies how Sebald’s critical work argued that the Holocaust “represented the culmination of a centuries-long process of [Jewish] assimilation to non-Jewish, bourgeois society” (

Martin 2013, p. 124). But, so far, almost no attention has been paid to the religious, rather than materialist, histories of European Jews and their influence on Sebald’s fiction.

In his introduction to Austerlitz, Wood alludes to the mystical, “visionary experience” of memory in the novel. This connection, between Austerlitz and mystical thought, is much more than a surface-level comparison. In what follows, I argue that Sebald’s text engages subtly but productively with aspects of Jewish mystical thinking, specifically the ilanot (Tree of Life) diagrams and Lurianic Kabbalah’s concept of tikkun (“repair” or “restoration”).

The critical mass of scholarship that has accumulated around W.G. Sebald tends to present

Austerlitz as Holocaust literature. Many scholars have focused on the importance of Sebald’s multi-media approach in relation to histories of violence, especially his inclusion of the photographic image.

2 These arguments generally focus on the possibilities (or impossibilities) of memory. Katie Fry discusses Sebald’s invocation of Proust and the metaphor of the mind as a darkroom full of photographs only to emphasize the ultimate impossibility of memory (

Fry 2018, p. 126). Stefanie Boese also discusses how Austerlitz uses material objects and images to affirm that ”remembering and forgetting the past are equally impossible” and photographs can only attest to their “having been” (

Boese 2016, p. 117). Richard Crownshaw also takes up the concept of Hirsch’s postmemory while avoiding the pitfalls of colonization because the photographs promise “not only deliverance from historicism but also the possibility of future memory work not consumed by a perfectly conceived, monumental, and therefore violent archive” (

Crownshaw 2004, p. 11).

Some also are concerned with the way the photograph works to construct time and narrative. J.J. Long considers how the networked nature of photographic postmemory “mirrors metaphorically the overall thematic of the verbal narrative” and Marie-Laure Ryan notes that the “ambiguous use of photos in texts that hover between the factual and the fictional” force the reader to ask questions about how the text is put together (

Long 2003, p. 137;

Ryan 2018, pp. 27, 43). Meanwhile, Mary Griffin Wilson’s work dispels the notion of photographic shock and instead argues for Sebald’s construction of a “non-chronological time” in the vein of Deleuze (

Wilson 2013, p. 51).

Throughout this range of work, scholars are overwhelmingly preoccupied with portraits, landscapes and cityscapes. Because they are indexical representations of people and places, these images necessarily stir up questions of factuality and documentation. They also activate a sense of presence.

3I am the last to argue against the importance of these images, but the scholarly focus on photography has, at times, overshadowed other visual media that inform Sebald’s depictions of Jewish loss. My goal is to develop the connection between

Austerlitz and the visual tradition of Jewish mysticism, a tradition with a “richness of the graphical heritage” that has often been overlooked (

Busi 2010, p. 33). As James Draney productively points out, “elegiac encounters with residual technologies informed Sebald’s literary aesthetic” (

Draney 2022, p. 155). While Draney’s focus is on the absence of new media in Sebald’s work and the importance of a handwritten, paper world, this framing opens possibilities for thinking about the Kabbalah’s hand-drawn and printed diagrams.

Reading Sebald alongside trends in Jewish mystical thought reveals a method of literary and visual representation that attends to both presence and absence via a layered temporality. In this way, the

Austerlitz considers the targets of genocide before their murders as well as the absence left in the wake of such loss. As the novel travels through museums, metro stations, archives and bazaars, the reader is confronted with memories of the Holocaust as part of a

tikkun-like process of (re)creation.

4 In this analysis, I emphasize the importance of graphic visualizations of information, especially the

ilanot, or “tree” diagrams of the Kabbalah. Both the narrative’s

tikkun-like structure and the presence of diagrams underscore an intellectual and artistic link to a Jewish history which carry broader implications for how unpacking theories of memory like Marianne Hirsch’s influential concept of postmemory (

Hirsch 2008).

2. W.G. Sebald and the Holocaust

Depictions of loss in both the literary and visual arts pose several problems, one of which is the question of how to recall a loss without artificially filling in or effacing the absence so central to its being. Revisiting the loss of the Holocaust and recalling it in a way that enables both feeling and understanding requires a paradox: the preservation of a sense of absence. Undoubtedly, first-hand testimonies will remain an invaluable asset. At the same time, forms of memory that do not rely on eye-witness testimonies also significantly contribute to a construction of the past.

Sebald’s own experience with the Holocaust was one shrouded in darkness and silence. Accordingly, in his work “the Holocaust functioned as a kind of formal black hole, drawing in characters and narratives by the force of gravity, but remaining detectable only indirectly” (

Martin 2013, p. 123). Indeed, the Holocaust was a sort of formal black hole not only in Sebald’s writing, but in his life. Born one year before the end of WWII in the small town of Wertach, the German author grew up in isolation, buffered from any knowledge of German atrocities. Considering their upbringing, Sebald’s sister explained “I never even knew what a Jew was” (

Angier 2021, p. 5). At the age of 17 he saw a film about the concentration camps in school, which greatly affected him. Shortly thereafter he moved to England for university, where he lived for the rest of his life. As an emigrant to the UK, Sebald spent much of his academic and creative career trying to unspool the silence that shrouded his parents and grandparents’ pasts, including their role in the war. Perhaps because he could “never get either of his parents to talk about the past”, he resorted to retracing the past himself, piecing together bits and pieces from archives, photographs, and films (

Angier 2021, p. 5).

Rather than address memory in terms of ability (what or how the characters are

able to remember and what this says about our own memories) as many scholars have effectively done, I propose a focus on the process of memory.

5 Sebald’s works have had an enormous impact on American academic discourses on the Holocaust, history, witnessing and the problem of memory (interestingly, his novels have not been as enthusiastically greeted in his native Germany).

6 But unlike many of the authors labeled “Holocaust writers”, Sebald is not Jewish. His work is deeply involved in the process of encountering the Holocaust’s destructive past through a cultural connection to the perpetrators of genocide rather than that of the survivors. As an adult, he looked upon the history he was taught in grade school with a sense of horror, realizing that he had grown up amongst perpetrators. With this realization, he turned, in his own scholarship, to twentieth century Jewish thinkers, especially Gershom Scholem.

Austerlitz, therefore, is a story caught somewhere between the worlds of personal memory and institutional history. Sebald describes this in-betweenness as “the history of countless places and objects which themselves have no power of memory” which similar to “straw mattresses […] had become thinner and shorter because the chaff in them disintegrated over the years” (24). Instead of an attempt to completely preserve these memories (to refill the mattresses, as it were), Sebald is interested in representing the ways in which the past disintegrates and the ripples of loss produced by violent events. Austerlitz reveals a process of memory that productively shows the possibilities of witnessing without witnesses and is, at its heart, profoundly influenced by mystical thinking.

In Sebald’s work, attending to this type of memory requires a balance between the known and the unknown, the remembered and the forgotten. It is a method which preserves the memory of those who were murdered, while also acknowledging the empty space they left behind. This serves to create an ethics of memory that swaps the glow of nostalgia for the eerie light of melancholy. It preserves loss in all its paradoxes and, through its complex temporality, requires that the reader reckon with the echoes of loss and violence, and the structures that supported such violence, as they continue to exist in the present. Simply put, Sebald presents his readers with a process of memory that refuses to stay neatly within the confines of the past and, instead, casts a questioning light on the present.

The buried nature of Austerlitz’s memories—he has the compounding traumas of losing his parents at a young age and having his adopted parents obscure his true origins—alongside the nested narrative form of the novel—an unnamed Sebald-like narrator, rather than Austerlitz himself, retells the story—call into question the veracity of Austerlitz’s recollections. There are several moments in the book wherein the narrator details Austerlitz’s pursuit of a fragmented memory only to reveal that this memory is false or incorrectly contextualized. One such revelation occurs during Austerlitz’s search for an image of his mother, Agáta. After going to great lengths to procure the Nazi propaganda film of the Terezín camp (the last known location of his mother), he stops at a still in which he sees a young woman that “looks, so I tell myself as I watch, just as I imagined the singer Agáta from my faint memories and the few other clues to her appearance” (

Sebald 2001, p. 251).

This bewildering mix of imagination, memory, and detective work tells us more about the process of Austerlitz’s recollection than its product, an emphasis which is confirmed when, two pages later, the reader finds that the film still is not Agáta before being presented with a newspaper clipping of a different woman. While Austerlitz accepts this image as truthful (Vera identifies his mother for him) the reader has, at this point, been exposed to enough gaps in the recollections of others to sniff suspiciously at any object of memory that remains fixed in a singular notion of truthfulness.

3. Mysticism and the Process of Remembrance

Both

Austerlitz and Jewish mystical thought are concerned with how to imagine and engage with experiences that, while not material in the present, are nonetheless perplexingly palpable. Similar to Austerlitz’s search for his long-gone parents, the mystic’s search for God engages with “the conflict of experiencing an almost tangible object of his or her vision, on the one hand, and with the stated normative belief that God in his true nature is incorporeal and hence invisible on the other” (

Wolfson 1994, p. 3). This tension, between the visible and the invisible, the present and the absent, is, according to Kabbalah scholar J.H. Chajes, very clearly born out in the diagrammatic tradition of the

ilanot which “treated—and attempted to visualize—the invisible” (

Chajes 2022, p. 4).

Grafting this tradition onto the twentieth century reveals an analog for the structure of post-Holocaust memory. The massively scaled destruction of Germany’s genocide is both incredibly tangible (the ubiquitous images of piled shoes, the ruins of the concentration camps) and, at the same time, overwhelmingly intangible (the bodies that filled those shoes are gone, the camps are empty). In many ways, the event lies beyond comprehension.

At their core mystical thought, across traditions, are attempts to comprehend the incomprehensible. Mystical methods reveal a constant negotiation between worlds: of the tangible and the intangible, of the present and the past with the goal of (at least partial) comprehension. And it is precisely this sort of negotiation that leads Austerlitz, the narrator, and the reader through the ghostly, yet materially vibrant, pages of Sebald’s final novel.

Austerlitz, like much of Sebald’s fiction, enacts a complex archeology as it digs through layers of the past. This is an actual talking point of the book; at Liverpool Street Station, Austerlitz identifies a “kind of heartache which, as I was beginning to sense was caused by the vortex of past time” (

Sebald 2001, p. 116). He then goes on to imaginatively burrow into the past through his location in the present. From the subway station, he recollects Londoners skating on the frozen Thames during the Little Ice Age, the draining of the city’s surrounding marshes, the priories of St. Mary of Bethlehem and the Bedlam Asylum, which stood on the same spot as the main station concourse until the seventeenth century. As he circles the events of WWII, Austerlitz muses on the excavation of the Broad Street Station in 1984, which revealed:

[O]ver four hundred skeletons underneath a taxi rank. I went there quite often at the time, said Austerlitz, partly because of my interest in architectural history and partly for other reasons which I could not explain even to myself, and I took photographs of the remains of the dead. I remember falling into conversation with one of the archeologists who told me that on average the skeletons of eight people had been found in every cubic meter of earth removed from the trench.

In an interview, Sebald remarks on the use of this macro lens of history, which at times mentions everything but the Holocaust: “The only way in which one can approach these things, in my view, is obliquely, tangentially, by reference rather than direct confrontation” (

Sebald 2010). He spells out the necessity of retelling histories of violence obliquely rather than plastering horrors on every page of his texts. Instead of a direct description of the genocide of European Jews,

Austerlitz stitches together a collection of documents, quotations, visual objects, and narratives to gesture towards loss, a practice of literary collage (

Angier 2021, p. 411).

Similar to Sebald’s fiction, the esoteric tradition of Kabbalah is historically layered and draws from an eclectic spread of texts. The Kabbalah, which literally translates to “tradition,” refers to a wide-ranging mystical movement that emerged over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries from the south of France (

Fine 2002, p. 18;

Chajes 2022, p. 2). Texts like the

Zohar,

Sefer Yetzirah and

Bahir claim an ancient, oral lineage but were likely of medieval origin. After their appearance in Europe, the extensive study of Kabbalistic texts was revived in the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century and German Romanticism in the nineteenth century. This moment of renewed interest in mysticism gave “a European flavor to Jewish thought” of the twentieth century (

Busi 2010, p. 36).

In the twentieth century, Jewish historian and philosopher Gershom Scholem brought the study of Jewish mystical thought into academic and secular circles in Germany, and later in Israel. While some of the conclusions that Scholem drew, especially around messianism, are still being debated by scholars like Moshe Idel, it is nevertheless “impossible to overestimate the profound influence which the comprehensive historical schemes first proposed by Gershom Scholem have had on Jewish scholarship” (

Idel 1993, p. 79). As such, when I discuss the Kabbalah in relation to

Austerlitz, I am primarily focusing on Scholem because this is the work that Sebald was familiar with and had access to.

Sebald was both aware of and interested in Scholem’s scholarship. In 1972, he wrote a letter to request Scholem’s support on a project on Jewish assimilation and literary failure. While the collaboration never took place, Sebald continued to critically engage with Scholem’s writing on mysticism and messianism. Messianism, which Scholem ties to

tikkun and Lurianic Kabbalah, is the topic of Sebald’s paper “The Law of Ignominy: Authority, Messianism and Exile in

The Castle”, where he “worked closely with Scholem’s texts in analyzing the revolutionary and mystical prowess of Kafka’s characters” (

Martin 2013, p. 134).

At the same time, Scholem tended to ignore the visual aspects of Kabbalah, claiming that the diagrams hid more than they revealed. To fill in these gaps, I turn to Chajes, whose recent work on the diagrams of the Kabbalah fill in some of the gaps that Scholem left. Attending to the underlying mysticism in Sebald’s fictional work, as well as his scholarly publications, reveals ways of reading Jewish experience on its own terms by using histories and stories within the rich and varied traditions of Jewish thought and visual culture. This move, in turn, fills an important gap in the corpus of Sebald scholarship, which rarely focuses on questions of Jewish intellectual history despite his designation as a Holocaust writer.

7But beyond Sebald as an individual author, this reading lays out a methodology which traces an often-obscured heritage of Jewish mystical thought in modern literature. As an immensely citational writer, drawing from a vast archive of philosophical and artistic traditions, to read Sebald is never to simply read Sebald (

Pearson 2008). It is, instead, to engage with a reservoir of other major (and minor) intellectual and artistic forces, among them mysticism as German-Jewish messianic discourse—in the form of Ernst Bloch, Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem and Franz Kafka—was of particular and continued interest to Sebald (

Hutchins 2011). This essay is therefore not only part of a project of recovery, but renewal through an exploration of the threads of mystical thought that are reinvigorated both within and beyond Sebald’s oeuvre.

In this recovery/renewal, traces of the Kabbalah can help detangle Sebald’s mess of memory, particularly as they intersect with the framework of Marianne Hirsch’s work on postmemory, which takes the Holocaust as its driving example. Hirsch maintains that “memory”, rather than “history”, is the appropriate word for her purposes because postmemory mimics the feelings and aesthetics of personal memory, even for “those who were not actually there to live an event” (

Hirsch 2008, p. 106).

Postmemory thus “reactivate[s]” and “reembody[ies]” the “distant social/national and archival/cultural memorial structures by reinvesting them with

resonant individual and familial forms of mediation and aesthetic expression” which echo or resonate long after the original participants and their families are gone (

Hirsch 2008, p. 111, emphasis, mine). Austerlitz experiences these ghostly echoes, playing out aspects of Hirsch’s theories. Because his parents were victims, not survivors, his search for first-hand narratives of their life throughout the novel is largely in vain. The concealed nature of Austerlitz’s history, which was hidden from him after his adoption, compounded with the loss of any written or oral record of his own history, requires another method of memory. Through his unconscious, sudden vision, he embodies aspects of Pierre Nora’s idea of “true” memory, which opposes the institutional archival forms of memory of history. True memory, for Nora, “has taken refuge in gestures and habits, in skills passed down by unspoken traditions, in the body’s inherent self-knowledge, in unstudied reflexes and ingrained memories” (

Nora 1989, p. 13).

At the same time, Austerlitz becomes a ragpicker of institutional history. Guided by his sudden visions, he is forced to search through material traces left in his parents’ wake. This search mirrors the research process, and it is mostly through objects—architecture, photographs, and archival documents—rather than direct communication—stories, diary entries, or family legend—that Austerlitz experiences postmemory. To use Hirsch’s own words about Austerlitz, these memories are experienced “so deeply” that it is as if they are his own.

Hirsch is deeply preoccupied with photography’s role in postmemory. In her writing on both

Austerlitz and Art Spiegelman’s

Maus, she considers how the photo is “a uniquely powerful medium for transmission of events that remain unimaginable” thanks to “[p]hotography’s promise to offer an access to the event itself” (

Hirsch 2008, p. 107). The photograph is also central to Sebald’s writing practice. As Angier points out in her biography and numerous interviews of the author, Sebald claimed that although he wrote fiction, most of his photographs were “‘authentic’ documents” (

Angier 2021, p. 20). The photographs that most often come up in the discussion of

Austerlitz are either images of people—the portrait of a young, costumed Austerlitz, Wittgenstein’s eyes, a newspaper clipping of his mother—or city scenes and architectural interiors—Liverpool station, Austerlitz’s study, the walls of Terezin. Meanwhile, scholars, including Hirsch, have paid less attention to the diagrams, maps, and city blueprints that populate the novel’s pages.

These diagrammatic images hover somewhere between a photograph and a print. They are often reproductions of found images and objects that Sebald stumbled upon and reproduced with the help of the photographer Michael Brandon-Jones.

8 These images, then, do not offer access to an acute, singular event or a specific individual in the way that Hirsch discusses. Rather, they speak to a methodology of retracing and reexperiencing the past in a way that revitalizes Hirsch’s ideas. They act, quite literally, as mnemonic maps, showing the process, the route to memory, without showing what one will ultimately uncover.

4. Tikkun and Fragmented Memories

When wandering through the former concentration camp and ghetto of Terezín, Austerlitz viscerally encounters the past: “It suddenly seemed to me, with the greatest clarity, that they had never been taken away after all, but were still living crammed into those buildings and basements and attics”. In this moment, it is as if he were imprisoned in Terezín alongside his mother and the sixty thousand others forced to inhabit “a built up area of one square kilometer at the most” (

Sebald 2001, p. 200). What

Austerlitz reveals in this moment is the possibility of memory located in space as much as it is in time, something akin to what Pierre Nora discusses in the concept of

les lieux de mémoire. For Nora, there is a “problem of the embodiment of memory in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists”. He goes on to explain that “there are lieux de memoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de memoire, real environments of memory” (

Nora 1989, p. 7). Austerlitz’s social environment of memory no longer exists, but an encounter with the past is still possible in memorial spaces.

Austerlitz’s spatial encounter with his mother and the “sixty-thousand others” of Terezín is more than a hazy memory or historical realization; it is a visceral experience. His sudden and claustrophobic vision defies the laws of time and space, lending a mystical flavor to Nora’s formulation of sites of memory. Austerlitz’s realization, which dawns “suddenly” and with the “greatest clarity” of the mystic in a visionary moment, enables the impossible: a tangible communion with the intangible.

Confronted with Terezín’s inhabitants, Austerlitz reflects that he feels “more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking according to a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like” (

Sebald 2001, p. 185). The reorganization of time into an inscrutable “higher order” flattens the distinction between past, present and future in favor of an interlocking spatiality. Kabbalistic scholarship identifies a similar impulse in mystical texts. Scholem explains that, for the mystic, “the past was never completely past. It is still with us, it still has a small opening to the present, or even into the future” (

Scholem 1997, p. 158).

9 In spatializing temporality and threading the past through the eye of the present, Sebald takes a page from Scholem’s book, illustrating the dynamic exchange between the dead and the living. This echoes Hirsch’s assertion: “[P]ostmemory’s connection to the past is thus not actually mediated by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation” (

Hirsch 2008, p. 105). The overlap between Scholem and Sebald’s conceptions of the past sheds new light on Hirsch because it foregrounds a past that is not only dominated by the “overwhelming inherited memories” of “traumatic events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension”, but also gestures towards an intellectual inheritance that predates WWII (

Hirsch 2008, p. 105).

The spatialization and interwoven nature of time in Sebald’s novel is also a key feature of the Lurianic concept of

tikkun. Scholem describes

tikkun, which is translated variously as “mending”, “correction”, “restoration”, as the “process of restoration of all things to their proper path and place, […] the entire world process, and of human history” (

Scholem 1997, p. 151).

10 Daniel Horowitz further elaborates on

tikkun as a series of actions which address, or rectify, the flawed nature of creation through “‘repair’ or ‘restoration’ of these flaws” (

Horowitz 2016, p. 225). This restoration, which refashions the fabric of “human history”, is by nature a temporal process: it works to mend the destruction of the past through the means of the present.

Austerlitz is flooded with attempts at this sort of recreation, and perhaps its impossibility. Vera, reflecting on several photographs of Austerlitz’s childhood, participates in a

tikkun process when she observes the way memory swells beyond the survivor: “As if the pictures had a memory of their own and remembered us, remembered the roles that we, the survivors,

and those no longer among us had played in our former lives” (

Sebald 2001, p. 182, emphasis, mine). The photograph in this scene becomes a form of posthuman memory, a way to collect the past and, in theory, attempt to piece it together despite the destruction of “those no longer among us”. Both Austerlitz and Vera’s reaction to these photographs is

tikkun-like: they try to place the images by determining the where, when and who of these photographic shadows. With this, they attempt to restore the images and their associated memories to their “proper place” within a history that is both personal and collective. But perhaps more importantly for our discussion of

tikkun, both characters creatively engage with these images: they imagine that it is “as if” the photographs have a memory, and project life onto them by suggesting “the impression […] of something stirring in them” in the form of melancholic sighs (

Sebald 2001, p. 182).

Austerlitz marks the perfection of a “unique method of literary collage,” in which history and memory are the raw materials (

Angier 2021, p. 411). Lurianic

tikkun is also an art of collage, an attempt to deal with the failure of creation via acts of recreation.

11 Tikkun is both born from brokenness and an attempt to remedy such brokenness. The result is an experience of fragmentation. Rabbi Isaac Luria, the sixteenth century mystic who most fully developed the concept of

tikkun, describes it as a response to the shattering of creation in “The Gate of Principles” from

The Tree of Life (Shaar Ha-Klalim shel Sefer Etz Haim):

But since the Base was shattered,

the light of the Base became revealed and

with the great power transmitted to Sovereignty,

Sovereignty also shattered—but not completely.

A new entity (Partzuf) was formed

after the restoration (tikkun);

and Sovereignty merited a complete entity

would be created from her,

even though she is only an atomic point (nekudah)

and not a complete molecule.12

The restoration (

tikkun) comes after a partial shattering and promises to create “a complete entity” from a fragment, “an

atomic point (nekudah) and not a complete molecule” (

Vital 2005, p. 18).

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi—a survivor of the Holocaust and a founder of the Jewish Renewal movement—offers up a helpful (and, in true Sebaldian fashion, image-based) way of conceptualizing

tikkun as a constructive, creative process even as it is couched in destruction. For him,

tikkun mimics the construction of a stained-glass window (

Horowitz 2016, p. 226). By joining shattered fragments,

tikkun works to create a new whole through a process of collage. The result is an object that is both unified and inherently fragmented; a spatialized representation of different temporalities which exist on one plane.

For Sebald, the

tikkun of memory embodies not only elements of mysticism, but a psychoanalytic sensibility as well. Previous works have posited a foundational relationship between Jewish mysticism and Freud’s development of psychoanalysis (

Bakan 1958) and there is a well-established basis for thinking about Sebald in psychoanalytic terms (

Santner 2006, p. 136;

Ning 2020;

Hirsch 2012). The overlap between Schachter-Shalomi’s stained-glass window and what psychoanalyst Adam Phillips calls “creative memory”—which finds “ways of making the previously unacceptable accessible through redescription or redepiction”—points to how access to the past requires a variety of viewpoints and intellectual histories (

Phillips 1994, p. 32).

Sebald’s repertoire is composed not only of personal memories but of institutional, historical objects and documents. While postmemory and creative memory are modeled after forms of individual memories (even if those memories are imaginatively constructed),

tikkun is different. It is a (re)collection of the world’s fragments, a process of mystical collection that includes institutional, historical, and cultural memories that far predate the violent event being remembered.

13 The very act of connecting Austerlitz’s memorial research with

tikkun is a part of the process in which it participates.

Similar to Schachter-Shalomi’s stained-glass analogy,

Austerlitz is full of images of fragmentation. Fragments populate the text and the narrator expresses an intense interest in the ways in which they are reintegrated (or not) into a cohesive whole. This motif resonates across the images and the language of the text, often through the invocation of glass. Glass architecture’s segmented panes gesture towards both fragmentation and unity and provide a fragmentary backdrop to Austerlitz’s peregrinations (

Figure 1). But this glass-like fragmentation is also linguistic. Descriptions and recollections of historical battles recombine fragments of history (we can think, even, of the name “Austerlitz” which is of course not only the main character, but the battle of Austerlitz in the Napoleonic wars as well as a subway station) and are “constantly forming into new patterns […] like crystals of glass in a kaleidoscope” (

Sebald 2001, p. 71).

In the same way that a kaleidoscope forms new patterns out of fragments as the viewer turns the lens, the disparate pieces of Sebald’s language form a new pattern of the past as Austerlitz continues to collect information. These kaleidoscopic images of history become the foundational structure by which Sebald conceptualizes memory. Importantly, they are both visual and verbal.

The kaleidoscope of the past is always in the process of being reconstructed. Austerlitz admits, “these fragments of memory were part of my own life”, only to “not believe that everything had really happened as it did” while watching his old nanny, Vera, struggle “to pick up broken threads” of her narrative (

Sebald 2001, pp. 141, 205). For both Austerlitz and Vera, rearranging the shattered past into a memory solicits active engagement. It also requires an acknowledgement of a gap or an emptiness, an inability to fill in all the pieces, and certainly an inability to return to an original, unbroken state.

Austerlitz’s inability to create a single, complete image of his history owes much to the violence and loss that permeate that history. Shortly after Vera confirms the existence of the sky-blue shoes Austerlitz remembers his mother wearing, he experiences even more fragmentation, rather than wholeness: “I felt as if something were shattering inside my brain” (

Sebald 2001, p. 161). Verifying his memory of his mother’s shoes paradoxically shatters Austerlitz. As he uncovers the past by drawing closer to the image of his mother (arguably the absent center of his childhood), he faces even more fragmentation. This desire to weave together bits of the past, paired with the inability to do so completely and the impossibility of returning to the original state of things, is a central element of both

tikkun and Sebald’s construction of memory.

Though Vera (a name that shares a root with the Latin verus, meaning “true”) offers Austerlitz an individual, first-person account of his childhood, much of the novel is dedicated to the exploration collective, institutional memory. Austerlitz wanders from libraries to public archives to train stations to piece together the feeling, as well as the facts, of history. The result is a multi-sensorial mix of images, touch, sound, place and language. Returning to a metro station where, according to Vera, his mother had once held him, Austerlitz tries to recreate a full-memory image of Agáta:

I could feel the touch of Agáta’s shoulder or see the picture on the front of the Charlie Chaplin comic which Vera had bought me for the journey, but as soon as I tried to hold one of these fragments fast, or get it into better focus, as it were, it disappeared into the emptiness revolving over my head.

Sebald uses the language of photography to describe Austerlitz’s fervent desire for an image of his mother. His desire to “get it into better focus”, ultimately fails, in part because the memorial mother flits about between the senses. She is tactile—he can feel her shoulder—but not visual. Instead, Charlie Chaplin, a face that was reproduced on screen, newspapers and magazines across the world, is the only visual image that sticks. Austerlitz grasps at the various sensory fragments which he has collected: from Vera, from his own body and from his surroundings. And yet, the fragments do not coalesce; they are marked by absence, the “emptiness revolving” over his head. The collection of scattered memories as well as the void into which they disappear indicate both presence and absence: a life before the Holocaust and the absence of that life after. Austerlitz’s experience of fragmentation illustrates the schism between language, sensation, and images while at the same time provocatively gesturing towards the creative potential of holding these fragments together.

Fragmentation of meaning alongside the sense that meaning is nonetheless possible, plays out in Austerlitz’s experiences with language which becomes, at times, a hopeless jumble of fragments. Language dissolves into images: “Sentences resolved themselves into a series of separate words, the words into random sets of letters, the letters into disjointed signs, and those signs into a blue-gray trail gleaming silver here and there, excreted and left behind it by some crawling creature” (

Sebald 2001, p. 124). Similar to the attempt to fuse the fragments of his mother’s shoulder and a Charlie Chaplin comic to recreate a childhood scene, the fragments of language Austerlitz describes come together to produce a negation, rather than a positive presence. The broken bits of language, the “disjointed signs”, merge, but they do so to indicate a fragmentary trace: the ghostly trail of a creature who remains inaccessible. All we can see is the materiality of what was “left behind”.

Again, this mimics the structure of

tikkun. Scholem explains that

tikkun is the process by which one gathers the “sparks” of original creation which have “descended into the depth and were imprisoned there by the powers of darkness or the “shells” made from the broken vessels” (

Scholem 1997, p. 151).

The Bahir, (or Book of Bright, an early and important mystical text and midrash of the book of Genesis) describes how these sparks are emanations of God, also known as the

sefirot, which were placed into vessels at the beginning of creation. But the vessels, being imperfect, shattered and left a second layer of creation. This second creation is the fragmented shells which now populate our world (

The Bahir,

Kaplan 1979).

15In his introduction to the University of Haifa’s Ilanot Project (an online catalogue of Kabbalistic diagrams found in manuscripts and books from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century), J.H. Chajes explains that the emanations of God (the sefirot) are part of the process of tikkun. He also notes that this relationship is often visualized in the Kabbalah:

As hypostatic facets of the Divine, the sefirot also serve as addresses for intentional prayer and as the objects of human efforts to restore their lost harmony. Such assistance is known by the term tikkun, referring to the repair and enhancement of the sefirotic network. The interface between God and creation is everywhere and it is broken; this, in a nutshell, is the compelling pathos of Kabbalah. Understanding the sefirotic code underlying all things and performing such knowledge is the work of the kabbalist.

(Chajes, “A Very Brief History of the Ilan Genre”)

Sebald’s fiction creates an interface with the material world of the past and present in a way that is strikingly similar: in photographs, fortress walls, old books and discarded shoes, traces of extinguished life still glimmer. These glimmers populate the novel. Encounters with a fragmented material world catapult the characters into real and imagined histories. This fragmentation can, of course, be physical (for example, the disintegration of the Terezín propaganda film) but it can also be temporal, in which the object is severed from its past. Sebald expands on this sort of temporal fragmentation in a 1998 interview with Michaël Zeeman, where he explains that the images included in his text (which, in Austerlitz, are more often of objects, architecture, or landscapes than of people) “rescue something out of that stream of history that keeps rushing past” (

Sebald 2006).

Perhaps one of the most acute experiences of this severing/rescuing takes place as Austerlitz is standing in front of the Antikos Bazar in Terezín. Observing the hoard of anonymous objects, tossed ashore on the banks of the stream of history, he starts imaginatively engaging with the very history from which they are separated. In a lamp, he contemplates “the endless landscape painted […] in fine brushstrokes, showing a river running quietly through perhaps Bohemia or perhaps Brazil?”(

Sebald 2001, p. 196). At the same time, he hazards far-flung guesses at the details behind this material history (are we looking at Bohemia or Brazil?), Austerlitz asks questions of narrative and meaning:

[W]hat, I asked myself, said Austerlitz, might be the significance of the river never rising from any source, never flowing out into any sea, but always back into itself, what was the meaning of veverka, the squirrel forever perched in the same position, or, of the ivory-colored porcelain group of a hero on horseback turning to look back?

The cyclical nature of these images (the river that flows back into itself), language (the narrative return of

veverka) and the frozen, yet somehow extended, sliver of time they capture, come together to form a material view of an individual’s memory of history. They are not emblems of an entire cultural history, but of a personal, memorial value that is both present and absent. Austerlitz sees the sparks of past lives within these things that “for reasons one could never know had outlived their former owners and survived the process of destruction.” But he also sees a spark of the present: “I could now see my own faint shadow image barely perceptible among them” (

Sebald 2001, p. 197). The lampshade, the painting, and the sculpture are each objects which contain a spark of the past that illuminates the present.

5. Ilan and the Diagrammatic Tradition

Austerlitz’s memories are collages, a tapestry of fragments pieced together from an expansive array of media, temporalities, genres and sources of knowledge. The image-studded and citational pages of the novel align with another mystical framework: the

ilanot (“trees”), which are a diagram of the

sefirot (“the ten luminous emanations” of God).

16 In the

Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Creation), the

sefirot are visual representations of the ten emanations of God and suggest a path towards a deeper understanding of God. They are often depicted visually and function as a map for the devoted mystic’s journey.

While modern scholars of Kabbalah, like Scholem and Moshe Idel, have largely ignored the importance of the

ilan because of a “deep-rooted bias against visual forms of knowledge”, Chajes has devoted much of his career to these graphic illustrations of the divine (

Chajes 2022, p. 2). Chajes reads the

ilanot as pedagogical images that “serve devotional ends” and “invite the contemplative on a journey of imaginal pilgrimage (

Chajes 2022, p. 8). Through these diagrams, the mystic is guided on a pathway through each different aspect of God (

Keter—the Divine Crown,

Hokhmah—Wisdom,

Binah—Understanding,

Hesed—Mercy,

Din—Justice,

Tif’eret—Beauty,

Nezah—Eternity,

Hod—Glory,

Yesod—Foundation,

Shekhinah—God’s Presence in the World), which derive their meaning in relation to the other

sefirot while also retaining their individual identities.

The image below (

Figure 2) shows a simplified version of an

ilan with a Kabbalist lost in contemplation. This popular woodcut has been reproduced many times, but originally appeared as the title page of Paulus Ricius’ 1516

Portae Lucis, the Latin translation of the thirteenth-century Castilian R. Joseph Gikatilla’s

Shaarey Orah (

Chajes 2020, p. 246).

Disorienting by nature, the complexities of the

sefirot are often approached visually, through diagrammatic visualizations. These arboreal schematics moved from the “classical” models, a style which reached its apotheosis with the

Magnificent Parchment in sixteenth century Italy, to the Lurianic

ilanot of the mid-seventeenth century.

17 But both versions of

ilanot seek to represent that which is intangible, “a reference to the visible power of the invisible form of the divine” (

Wolfson 1994, p. 9). The tension between the visible and invisible already discussed in relation to

tikkun is thrown into even sharper relief in the

ilanot because they are literally visualized, producing an instructive “image” of God in an otherwise iconoclastic tradition. It is exactly this turn to visualization, rather than simply relying on language, that underscores the importance of both word and image for experiences of Jewish memory and postmemory in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

18Much in the same vein as Sebald’s fiction, the diagrammatic

ilanot exist at the very intersection of word and image. Chajes argues that both printed text and visualization strategies are key to the

ilanot: “The two are mutually interdependent. Together, and only together, they establish the meaning of an

ilan” (

Chajes 2022, p. 8). Sebald’s approach to the intersection of text and images carries some of the same ambivalence found in

ilanot. Images are a necessary tool for understanding in both the novel and mystical thought. To interpret the complexities of the Kabbalah, the role of the “diagram to commentary, and of form to function” is absolutely central (

Segol 2012, p. 79).

At the same time, these images resist easy meaning-making. The ilanot have a paradoxical function. They orient the viewer and offer a map to further a human understanding of God while at the same time profoundly disorienting her, pointing to an impossible or paradoxical understanding of space. To achieve this, the diagrams remain iconoclastic in the sense that they do not function as a simple one-to-one game of representation in the way that other religious images (such as icons or depictions of saints) might. The tree diagrams are “indexical rather than iconic” and “visualize abstract relations” (Chajes, “A Very Brief History of the Ilan Genre”). Like light leaving a trace on photo-sensitive paper, the ilan points to a presence beyond itself by registering the emanations of a spiritual light.

Austerlitz points out a similarly delicate balance inherent in the image. Austerlitz’s beloved history teacher, Hilary, explains: “Our concern with history […] is a concern with preformed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered” (

Sebald 2001, p. 72). For Hilary, an image that only orients, that claims to explain (i.e., “This is how it really was”) leads viewers away from the truth. And yet, despite the risks inherent in using images to further understanding, both Sebald’s text and the

Sefer Yetzirah make use of specific forms of visualization, namely, a visualization of (dis)orientation.

The diagrams of the

sefirot and Austerlitz’s images avoid the pitfalls of the “preformed images” of history because they do not claim an unmediated, direct form of representation. Instead, they nudge their readers to discover that which lies in excess of the image, “away from it all”. While not revealing an intact, totalizing truth,

ilanot nevertheless put the reader on a searching path to understand God’s true nature by piecing together the different components of the diagram. In this way, the diagrams act less as preformed images—in the below

ilan (

Figure 3) the “image” of God is unformed in that it requires the viewer’s active participation as she learns to piece the components together—than as participatory images.

Rather than present an entirely intact divine truth, these images point to a participatory truth that remains “somewhere as yet undiscovered” (

Sebald 2001, p. 72). They encourage the act of discovery because they are opaque, ambivalent and reliant on interpretation from the conscientious kabbalist. The instructive nature at the heart of these images—their pedagogy—asks the reader/viewer to critically reflect on these images and assemble their own meanings from the abstracted, often confusing, combination of parts.

Many of Sebald’s photographs and blueprints also avoid the pitfalls of the preformed images of history and points to a truth that lies elsewhere and can only be accessed through participation. Because these images are dropped into the text without captions, the reader must imaginatively work to place them within the narrative. This (dis)orientation works to signal an absence, a missing piece, something “elsewhere” (

Sebald 2001, p. 72). In other words, Sebald’s images, similar to the mystical diagrams, seek to paradoxically represent the unrepresentable—in this case, a loss or absence—and, in so doing, produce a deeper, participatory understanding of that loss.

But the question remains: how do some images, and not others, get the reader to the “elsewhere” of Hilary’s history? I’ve discussed that, for Sebald, the “preformed” images obscure the past’s as-yet-undiscovered truth because they are treated as transparent windows onto history.

19 Thus, they inspire a passive approach. Encountering iconic (and undoubtedly important) images of the past does not require active engagement because the viewer already assumes that she knows what she is seeing (and takes for granted that what she is seeing is true, i.e., the total and whole story). This leaves little room for the questions that fuel the viewer to pursue a path of personal discovery that is often aligned with memory rather than history.

Photographs of the concentration camps are precisely the type of preformed image Hilary balks at. While these images served a critical function in documenting the horrors of the camps and spreading the knowledge of genocide in the immediate aftermath of WWII, they have now been circulated to such an extent that they have joined the ranks of the preformed images of history. Part of this comes from how photographic images circulate in our cultural consciousness, a phenomenon Susan Sontag addresses in

On Photography. As photographic images of historical horrors and atrocities become familiar to the public, they lose their novelty. The more familiar they become, the more they contribute to a sense that the past is both knowable—the public can

see what happened—and inevitable—it could not have happened any other way.

20 Photographs of mass graves, for instance, lead us to assume that we are seeing “the whole thing”, an assumption that, in fact, obscures other truths: the impossibility of seeing the whole thing precisely because of the immense absence that resulted because of this violence. In this, images blind, rather than reveal because their attempt at direct visualization obscures the fact that, when it comes to the past, there is always something missing, something ineffable, a question mark that can never wholly be dispelled.

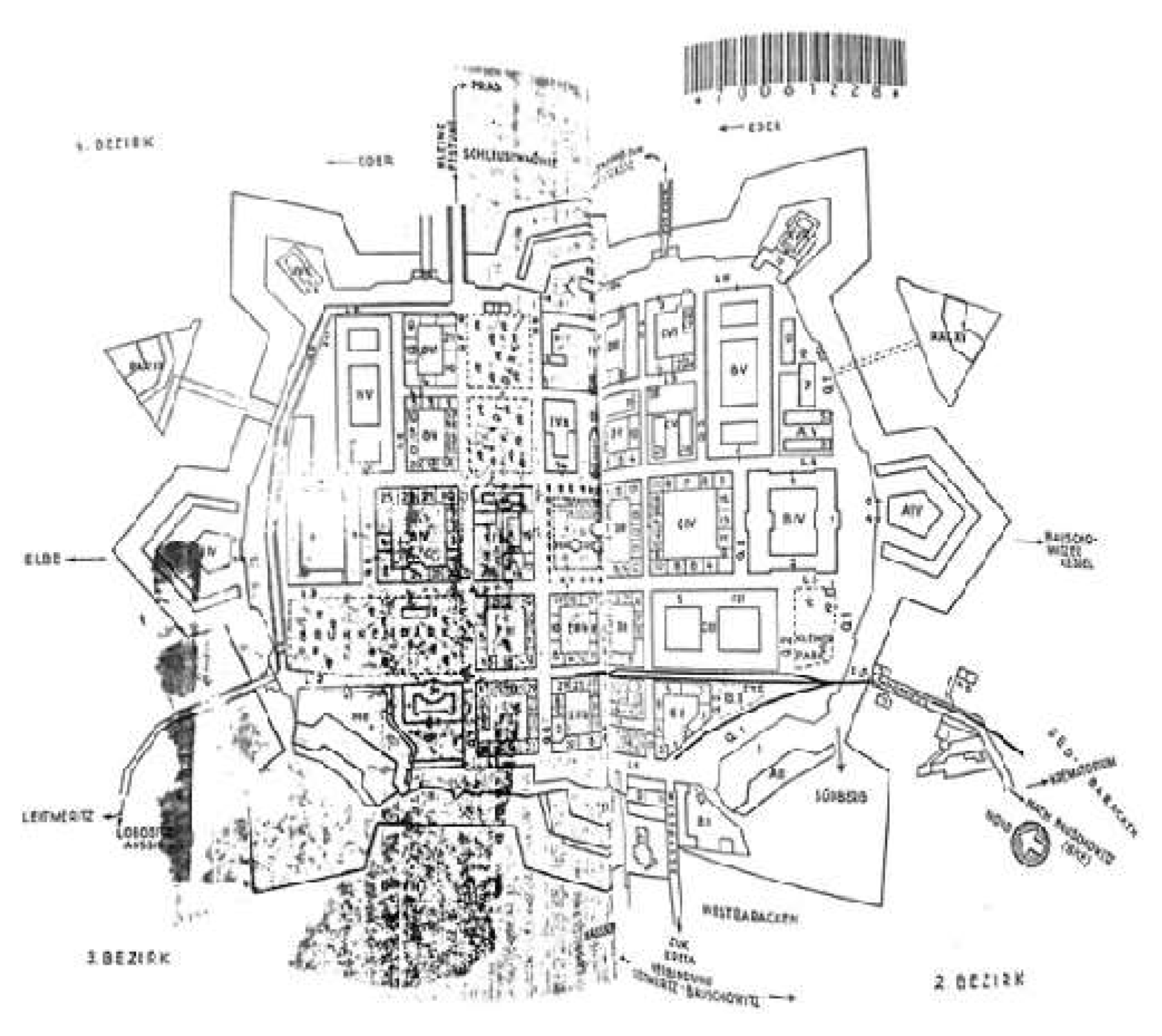

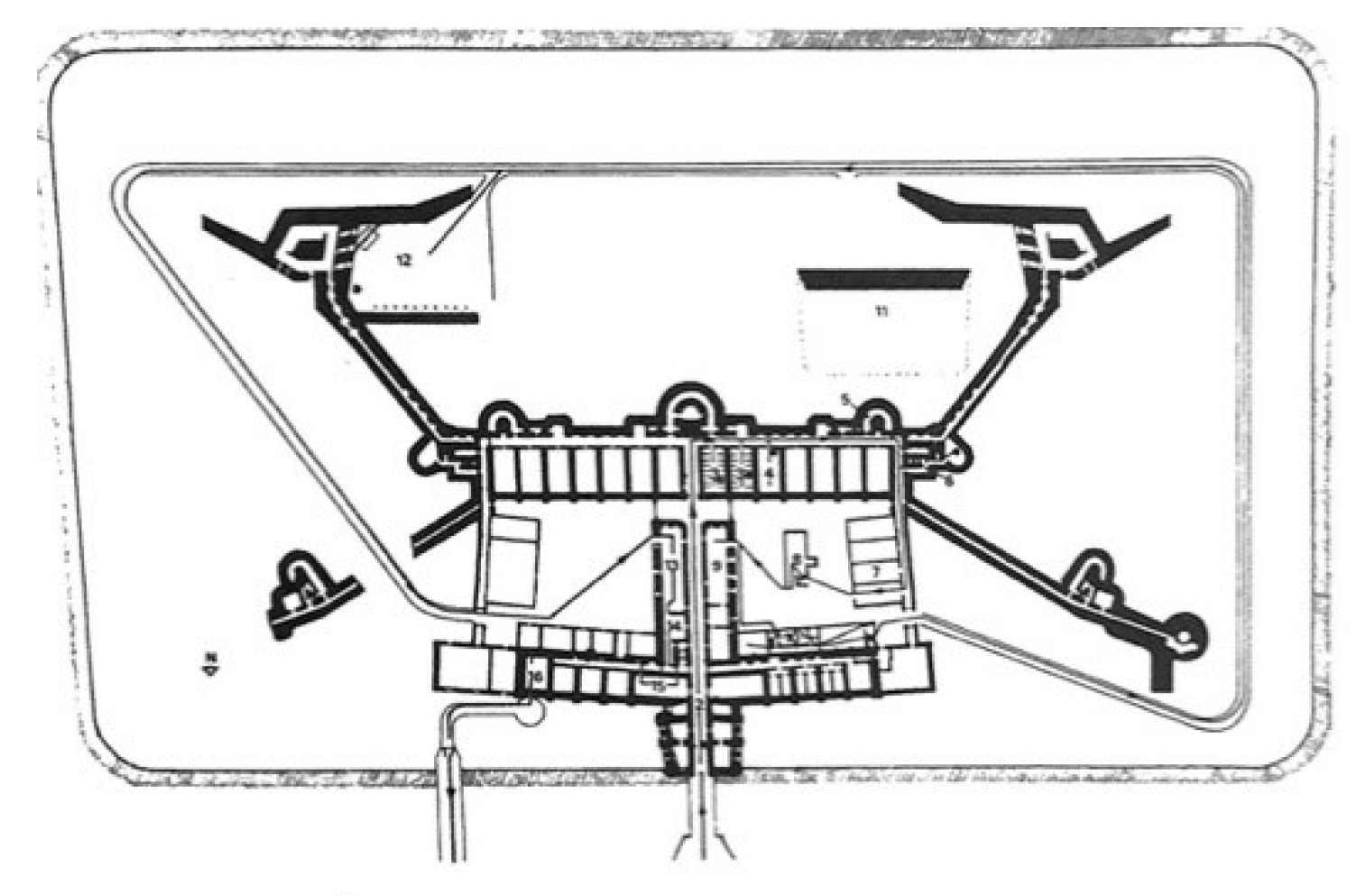

Austerlitz includes diagrammatic images, specifically architectural blueprints and bits of maps, that bear striking visual and methodological resemblances to the diagrams of the

sefirot. Rather than allowing the reader to “keep staring” at an image while “the truth lies elsewhere”,

ilanot diagrams point towards that “elsewhere”. As

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate, such images depict the relationships of parts to the whole. The visualization of this sort of relationality requires both a mental and physical movement as the viewer attempts to negotiate this complex web of relationships. Our eyes must travel around the diagram, rather than absorbing it as a whole, which is so often the case in other images (such as portraits or documentary photographs) that look like the “real” world. In this way, mysticism’s diagrams relay their message not by mimesis, but by acting as “tools for learning, thinking, for orienting, and for doing” (

Segol 2012, p. 8).

In his discussion of the sixteenth century kabbalist R. Moses Cordovero, Chajes notes that some kabbalistic diagrams depict a “topography of the Godhead” (

Chajes 2020, p. 245). Essentially, diagrams present a synthetic view that is imperceptible to the human eye in order to indicate complex, and often ineffable, systems. In comparing the

ilanot above with the below

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 from

Austerlitz, there are clear visual resonances. The

sefirot, maps and blueprints make use of a combination of circular and linear structures nested within one another or connected into a series of nodes. Sometimes these diagrams are rounded and encompassing. In

Figure 4,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 9 the smaller parts are subsumed within a larger whole. At other times—for example

Figure 5 and

Figure 8—they are circuit-like and use lines to connect different nodes. Each image, however, is engrossed in depicting a complex relationship between parts and the whole. This is achieved through an impossible conglomeration of perspectives—X-ray, cross section, and bird’s eye. The result is an absorbing sense of (dis)orientation that, in conjunction with printed language, requires active engagement on the part of the viewer/reader. In addition, both Sebald’s maps/diagrams and the

ilanot often exceed the frame of the page. They depict roads or channels (at the bottom and top) that gesture towards an elsewhere.

In the same way that the

sefirotic diagrams function as “important pedagogical tools” for thinking about the overlapping and intersecting nature of God, the blueprints in

Austerlitz skirt the pitfalls of Hilary’s preformed images (

Segol 2012). They instruct readers to explore a deeper understanding of history by embodying a complex and layered experience of temporality. The diagrams of Terezín (

Figure 7) parallel Austerlitz’s research on and physical exploration of the fortress, inviting the reader to consider the fortress’s uses before, during, and after WWII.

Beyond the specificity of the Terezín blueprint, Sebald uses blueprints and architectural diagrams to reference a web of material and spiritual heritages that might otherwise be unavailable to average readers. In their visual similarities and methodological frameworks, they nod towards an elite mystical tradition which predates the 19th-century architecture they depict. And yet, at the same time that these blueprints gesture towards a longer history, they act as oracles for a horrific future. Austerlitz explains that the architecture displayed in these prints “pointed in the direction of the catastrophic events already casting their shadows before them” (

Sebald 2001, p. 140). The curious combination of past, present, and future temporalities in Austerlitz’s claim is a collage of time, an attempt to illustrate the complex, non-linear, and diagrammatic ways in which fragmented instances of the past relate to the whole of human history.

In this, Sebald works with a distinctly visual experience of time.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 are at once visual diagrams which indicate a future (they were used as designs and instructions to build something that did not yet exist), the present (if used as a map they provide navigational instructions for standing structures), and the past (Austerlitz encounters most of these images as archival documents which preserve the memory of buildings that were long ago destroyed or modified). Within the fabric of the novel’s narrative, these diagrams embody past, present, and future concerns.

The diagrams are at odds with some of the other images in Austerlitz. Unlike the photographs or the film stills, they hover between abstraction and a concrete, physical reality. Similar to the diagrams of mysticism, they do not imprint on our brains in the way Hilary’s preformed images imprint, because they do not give the illusion of reality as perceived by the human eye. At the same time, they do depict a physical reality: the architectural layout of Terezín does reflect a material place, it simply does not pretend to be identical with that place.

Rather than show images from the concentration camps, Sebald opts for a level of abstraction that is pedagogical in nature. This requires the reader to peel back the layers of a material past to reveal the truth that lies at the heart of all memories of loss: the impossibility of ever truly returning. This represents the Holocaust in an oblique way because it represents an encounter with the paradox of presence and absence at the core of monumental loss.

To further underscore this point, Sebald does not include diagrams of just any architectural feature. Rather, he focuses on the concept of the fortress. Many of the diagrams in

Austerlitz are of defensive structures, primarily from the 19th century or earlier. Far from providing an adequate defense, these fortresses “drew attention to your weakest point” and proved “that everything was decided in movement, not in a state of rest” (

Sebald 2001, p. 16). Within the diagram of the fortress is both a representation of defense, but also the key to defeating those defenses. Similar to the diagrams of the

sefirot, these diagrams introduce a puzzle, a bewildering arrangement of fragments that can help unravel the tangled thread of the past.

The diagrammatic fortress represents a defensive impulse, a desire to block out intruders. Translated into the realm of Austerlitz’s memories of his childhood (or lack thereof), the fortress becomes a way to obscure the past. Austerlitz’s intruders are not physical armies, but the intruders of the painful memories of his personal past and cultural history. Dreaming that he is “at the innermost heart of a star-shaped fortress, a dungeon entirely cut off from the outside world, and I had to try finding my way into the open”, Austerlitz comes to the realization of “how little practice I had in using my memory, and conversely how hard I must always have tied to recollect as little as possible, abiding everything which related in any way to my unknown past” (

Sebald 2001, p. 139). These diagrams, therefore, stand in as guards against the internal armies of his own loss. On the other hand, by contemplating these diagrams through archival materials and the physical practice of walking through the structures, Austerlitz unlocks a past that is not reliant on the memories of survivors, first person narratives or lived experiences.

The diagrammatic blueprints of the fortresses in Austerlitz are similar to the ilanot in that they capture a presence through abstraction. This abstraction, in turn, reveals something about the structures of memory. The defenses depicted stand in as psychological, as well as physical, defenses and expose vulnerabilities to show the reader how to trace and understand these vulnerabilities. Thus, there is always something to be desired in the diagram: it represents a set of relations while also maintaining a curious distance from those relations. In other words, it can indicate both a presence and an absence.

Nevertheless, the two are inextricably linked. When exploring the written history of Terezín while in search of the memorial scraps of his mother, Austerlitz laments that the distance he had created from “my most distant past” now “seems unpardonable to me today”. This distance, he goes on to explain, has made conversations about Terezín impossible; “it is too late” he explains, to even talk to H.G. Adler, a survivor of Terezín who published the foundational

Theresienstadt 1941–1945: The Face of a Coerced Community in 1955 (

Sebald 2001, p. 236).

Instead, Austerlitz’s academic passion for 19th century architecture consumed his adulthood. Ultimately, it is this architecture that would hold, imprison and likely bring about the death of his mother. Reflecting on this, Austerlitz considers how:

[I]t is often our mightiest projects that most obviously betray the degree of our insecurity. The construction of fortifications […] clearly showed how we feel obliged to keep surrounding ourselves with defenses, built in successive phases as a precaution against any incursion by enemy powers, until the idea of concentric rings making their way steadily outward comes up against its natural limits.

These concentric rings do push the natural limits of memory, temporality and our ability to make sense of it all. While avoiding the traps of preformed images of history through (dis)orientation, the diagram also weaves together a vast range of historical experiences and forms, thus crafting a truly intermedial understanding of memory. It nevertheless hovers on the limits of human understanding. Sebald amasses archival records, animals, film, music, oral accounts and the written word are all woven together into a complex diagram of thought that gives more of a

sense of the past or a

feeling of it than any direct narrative. Similar to

ilanot, which pull “together cosmologies we might imagine separately to tell stories that seem unrelated”, Sebald’s diagrams weave a tapestry of the past from seemingly disconnected fragments and eras (

Segol 2012, p. 78–79). Images, alongside words, are necessary for such a tapestry because these cosmologies, which may seem disparate if only conveyed through the written word, are consolidated in the diagram which “depicts their relation and the mode of acting upon them” (

Segol 2012, p. 79).

6. Conclusions

I will conclude by returning to the scene from the beginning of this essay, in which Vera and Austerlitz examine two photos: one of an unidentified couple in front of a theater set and the other of a young Austerlitz dressed up to accompany his mother to a ball. By invoking these photos, Sebald suggests that the memorial quest of the protagonist is not simply material in nature (sifting through photographic remains) nor purely linguistic in structure (Vera’s fragmented explanation that goes along with the photographs), but requires both. For Austerlitz, negotiating access to the past relies on a mystical construction of both word and image in order to capture the complexities of the presence/absence which lies at the heart of memory. The dance between these categories—word and image, the intangible and tangible—connects Kabbalistic practices and Sebald’s fiction to reveal the way in which seemingly disparate intellectual and artistic traditions reinvigorate and remake one another in response to a crisis in modern memory. Moreover, they do so in a distinctly Jewish tradition.

Austerlitz is narratively founded on the main character’s obscured Jewish heritage. To read the novel, then, is also to read a lineage of Jewish thought. This lineage is, in turn, the key to trying to understand some of the problems surrounding memory and the Holocaust because it provides a structure that incorporates absence and offers up a methodology for gathering, without resolving, the fragmented nature of history, memory and what lies in the spaces between these two categories.

Sebald’s references to Austerlitz’s past and to Judaism are oblique and glancing. Rather than directly discussing the Torah or religious holidays, Sebald hints at a Jewish past and present in a more subtle way, asking the reader to connect the dots herself. One such example is the inclusion of an illustration from a Bible. Opening up to an image of the Israelite camp, Austerlitz explains, “I knew that my proper place was among the tiny figures populating the camp” because “[t]he children of Israel’s camp in the wilderness was closer to me than life in Bala, which I found more incomprehensible every day” (

Sebald 2001, pp. 55, 58). In addition to this, of the five images which act as centerfolds, three are related to Jewish history. Two represent the ancient (the Israelites camped in the desert as they flee Egypt) and the more recent past (a frame of the Theresienstadt ghetto film) (

Sebald 2001, pp. 56–57, 248). The other is a diagram of Terezín, the site of a ghetto and concentration camp (

Figure 5). The subtle structure achieved by weaving together references to a Jewish past through both images and oblique references cultivates a sense of Austerlitz’s Jewish identity while also revealing his distance from that identity, a distance that resulted from the schism of genocide’s violence.

This complements, and complicates, what Hirsch herself notes about Austerlitz, a text that “speaks somehow to a generation marked by a history to which they have lost even the distant and now barely “living connection”” (

Hirsch 2008, p. 120). Acknowledging the overlap between mysticism and

Austerlitz connects Sebald’s work to aspects of Jewish history and intellectual heritage beyond the Holocaust. The way in which postmemory aligns with structures of certain Jewish mystical beliefs—namely, the concept of

tikkun and the

ilanot diagrams—creates a subtle, but certainly present (rather than “distant” or “lost”) connection to generations of Jewish thought that predate the Holocaust. This connection is often overlooked because it is not predicated on a sense of familial belonging, but instead on a cultural heritage in a broader sense: an intellectual and artistic history.

Hirsch acknowledges this in the etymology of the term “postmemory”. In coining this word, she elaborates on the meaning of the “post”. The “post” of postmemory “shares the layering of these other ‘posts’” of postmodernism, postfeminism, posthumanism, and postcolonialism” (

Hirsch 2008, p. 106). Because it means both that which comes “after” (as is the case in postfeminism) but also the “troubling persistence of” (as is the case in postcolonialism), the term postmemory is necessarily layered and multitemporal, much in the same way as Sebald’s model of memory involving the memorial process of

tikkun and diagrammatic images.

Hirsch’s incisive description of the layered meanings of language and knowledge not only nods towards the process of archaeological history and the accumulation of memory, but also to the notion that creation is a process that is devoid of a “pure” origin. Acknowledging the linguistic layers behind any concept, Hirsch makes it clear that the creation of postmemory is a process of collection—one idea built on top of another in an endless formation without a discernible singular, point of origin. Pearson notes a similar process in Sebald, creating “a fertile engagement with earlier texts that contributes to the historical layering of his narratives” (262). Weaving together historical and intellectual traditions serves as a source of fertility by involving seemingly separate narratives (in this case, earlier texts) in the collective movement of tikkun memory. Sebald’s mystical intertextuality takes Hirsch’s notion of postmemory a step further by opting instead for a model of memory that draws from a vast array of sources—both familial and extra-familial, photographic and drawn, Jewish and secular.

Taking up the tone of what Michael Hutchins calls the “hopeful despondency” of modern Jewish mysticism, Austerlitz comes to an end in much the same way as it begins: with the fortress of Breendonk and with the image of a desk and papers (

Hutchins 2011, p. iii). While some of Austerlitz’s questions concerning his origins have been answered, he has uncovered many more that remain a mystery (such as his father’s story). A book that begins with a quest for the mother ends with the quest for the father, suggesting that this sort of pilgrimage, a pilgrimage backwards into the past, is ongoing. Again, this echoes the construction of the

sefirot, of which the

Sefer Yetzirah says, “Their end is fixed in their beginning” (

Yesirah 2004, p. 74).

Rather than construct a linear timeline, the narrative presents a spiraled structure, returning, but with a difference, to the past and carrying its newly gathered fragments forward into the present and, eventually the future. This spiral creates a way out of binarized experiences of the past. Rather than circling one of two drains—the particular, family memories told at the kitchen table, on a family vacation, in the photo album or the institutional histories of the archives, the textbooks, and the government records—Sebald borrows from the rich intellectual and mystical heritage of Jewish mysticism to provide a third option. In this, the reader encounters a view of the past that is both personal and collective, reads Jewish experience within a framework of Jewish thought, and that continues to impact and influence the present.