Work Addiction in a Buddhist Population from a Buddhist-Majority Country: A Report from Sri Lanka

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sri Lanka: The Background

1.2. The Buddhist Teachings

1.3. The Application of Buddhist Teachings in Addiction Treatment

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Work Addiction

2.2.2. Religiosity

2.2.3. Sociodemographics

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Missing Values

3.2. Prevalence of Work Addiction

3.3. Relationships Between Work Addiction and Sociodemographics

3.4. Moderation Models

3.4.1. Relationship Between Religiosity and Work Addiction: Gender as a Moderator

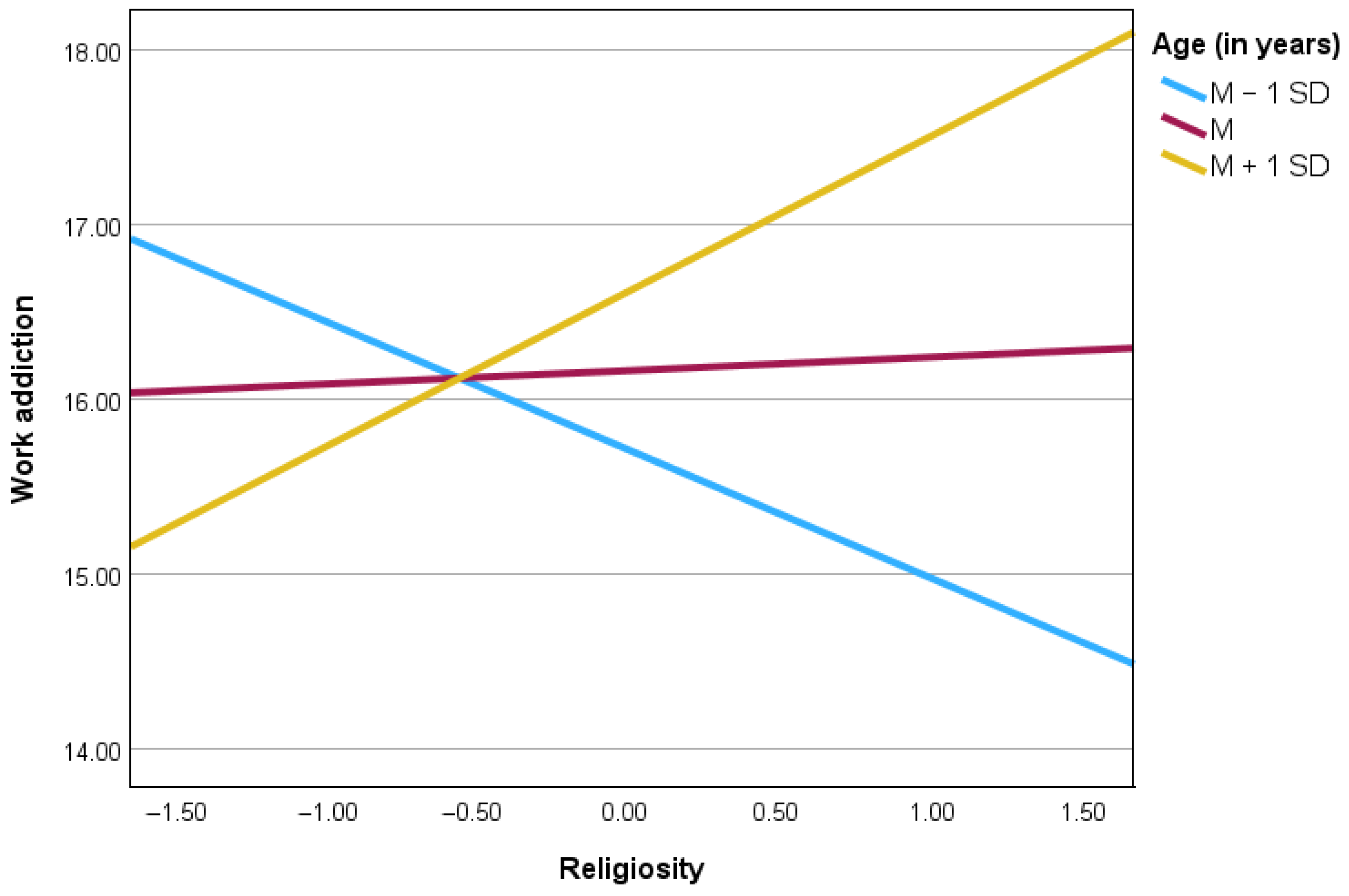

3.4.2. Relationship Between Religiosity and Work Addiction: Age as a Moderator

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Study

4.2. Metaphysical and Soteriological Meaning of Workaholism in Buddhism

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.4. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed. 2007. Assessment of Intrinsic Religiosity with a Single-Item Measure in a Sample of Arab Muslims. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 2: 211–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Abbas, and Abdullah Al-Owaihan. 2008. Islamic Work Ethic: A Critical Review. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 15: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Filip Borgen, Merjem Emma Torlo Djugum, Victoria Steen Sjåstad, and Ståle Pallesen. 2023. The Prevalence of Workaholism: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1252373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argue, Amy, David R. Johnson, and Lynn K. White. 1999. Age and Religiosity: Evidence from a Three-Wave Panel Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38: 423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, Paweł A. 2022. Work Addiction. In Behavioral Addictions. Conceptual, Clinical, Assessment, and Treatment Approaches. Edited by Halley M. Pontes. Cham: Springer, pp. 213–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, Paweł A. 2024. Work Addiction and Workaholism Are Synonymous: An Analysis of the Sources of Confusion (a Commentary on Morkevičiūtė and Endriulaitienė). International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroszko, Paweł A., Bernadette Kun, Aleksandra Buźniak, Stanisław Czerwiński, Zuzanna Schneider, Natalia Woropay-Hordziejewicz, Arnold Bakker, Cristian Balducci, Zsolt Demetrovics, Mark D. Griffiths, and et al. 2025. Perceived Coworkers’ Work Addiction: Scale Development and Associations with One’s Own Workaholism, Job Stress, and Job Satisfaction in 85 Cultures. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 14: 246–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atroszko, Paweł A., Zsolt Demetrovics, and Mark D. Griffiths. 2019. Beyond the Myths about Work Addiction: Toward a Consensus on Definition and Trajectories for Future Studies on Problematic Overworking: A Response to the Commentaries on: Ten Myths about Work Addiction (Griffiths et al., 2018). Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, Mark E. 1997. Wat Thamkrabok: Buddhist Drug Rehabilitation Program in Thailand. Substance Use & Misuse 32: 435–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrows, Paul, and William van Gordon. 2021. Ontological Addiction Theory and Mindfulness-Based Approaches in the Context of Addiction Theory and Treatment. Religions 12: 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiler-May, Angela, Rachel L. Williamson, Malissa A. Clark, and Nathan T. Carter. 2017. Gender Bias in the Measurement of Workaholism. Journal of Personality Assessment 99: 104–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengtson, Vern L., Norella M. Putney, Merril Silverstein, and Susan C. Harris. 2015. Does Religiousness Increase with Age? Age Changes and Generational Differences over 35 Years. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, Andy, Mohammad Saeed, James Ondracek, Mallory Sall, Zach Knipp, Tanner Gust, Courtney Gallagher, T. Martinez, and Sunny Li. 2021. Work Ethic across Generations in the Workplace. Effulgence-A Management Journal 19: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. 2000. The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, vol. 2, pp. 1843–47. Available online: https://www.bps.lk/bookshop-search.php?styp=l&d=02002001 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Bodhi Path Press. 2023. Digha Nikaya: The Life and Teachings of Buddha. Casper: WRITAT. Available online: https://books.google.com.vn/books?id=feRZ0AEACAAJ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Buddharakkhita, Acharya, trans. 1985. The Dhammapada: The Buddha’s Path to Freedom, 2nd ed. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. Available online: https://www.bps.lk/olib/bp/bp203s_Buddharakkhita_Dhammapada.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Buddhistdoor Global. 2016. Mithuru Mithuro: A Compassionate Friend to Drug Addicts in Sri Lanka. Buddhistdoor (blog). Available online: https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/mithuru-mithuro-a-compassionate-friend-to-drug-addicts-in-sri-lanka/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Buddho Foundation. 2023. Buddhist Schools: Theravada, Mahayana & Vajrayana. Buddho.Org (blog). Available online: https://buddho.org/buddhism-history-and-schools (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Celedonia, Karen L., and Elizabeth Nutt Williams. 2006. Craving the Spotlight: Buddhism, Narcissism, and the Desire for Fame. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 38: 216–24. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyńska, Edyta, Aleksandra Buźniak, Stanisław K. Czerwiński, Natalia Woropay-Hordziejewicz, Zuzanna Schneider, Toivo Aavik, Mladen Adamowic, Byron G. Adams, Sami M. Al-Mahjoob, Saad A. S. Almoshawah, and et al. 2025. The International Work Addiction Scale (IWAS): A Screening Tool for Clinical and Organizational Applications Validated in 85 Cultures from Six Continents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 14: 220–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, Malissa A., Jesse S. Michel, Ludmila Zhdanova, Shuang Y. Pui, and Boris B. Baltes. 2016. All Work and No Play? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates and Outcomes of Workaholism. Journal of Management 42: 1836–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zoysa, Piyanjali. 2013. The Use of Mindfulness Practice in the Treatment of a Case of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Sri Lanka. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zoysa, Piyanjali. 2016. When East Meets West: Reflections on the Use of Buddhist Mindfulness Practice in Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 362–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossi, Francesca, Alessandra Buja, and Laura Montecchio. 2022. Association between Religiosity or Spirituality and Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 980334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, Iwona, and Malwina Szpitalak. 2019. Gender Differences Regarding Workaholism and Work-Related Variables. Studia Humanistyczne AGH 18: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EconomyNext. 2023. Crisis-Hit Sri Lanka Sees Record Labour Migration as Rupee Collapse, High Inflation Weigh. EconomyNext (blog). Available online: https://economynext.com/crisis-hit-sri-lanka-sees-record-labour-migration-as-rupee-collapse-high-inflation-weigh-108055/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Garland, Eric L. 2016. Restructuring Reward Processing with Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement: Novel Therapeutic Mechanisms to Remediate Hedonic Dysregulation in Addiction, Stress, and Pain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1373: 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, Wilhelm, and Mabel Rickmers. 1953. Culavamsa: Being the More Recent Part of the Mahavamsa. Colombo: Ceylon Government Information Department. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldi, Tullio. 2019. Psychotherapy, Mindfulness and Buddhist Meditation. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Sam G. McFarland. 1972. Single vs. Multiple-Item Scales for Measuring Religious Values. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 11: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Susan E. McPherson. 1989. Intrinsic/Extrinsic Measurement: I/E-Revised and Single-Item Scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 348–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Mark, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Paweł A. Atroszko. 2018. Ten Myths about Work Addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 7: 845–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, Paramabandhu. 2014. Buddhist Approaches to Addiction Recovery. Religions 5: 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratana, Bhante Henepola. 2001. Eight Mindful Steps to Happiness: Walking the Buddha’s Path. Somerville: Wisdom Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2022. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Lin. 2018. A Review of Workaholism and Prospects. Open Journal of Social Sciences 6: 318–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huml, Matt R., Elizabeth A. Taylor, and Marlene A. Dixon. 2021. From Engaged Worker to Workaholic: A Mediated Model of Athletic Department Employees. European Sport Management Quarterly 21: 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, (Version 26.0). Armonk: IBM Corp.

- Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. 2022. Sri Lanka’s Deepening Economic Crisis: The Plight of the Poor. Talking Economics (blog). Available online: https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2022/07/18/sri-lankas-deepening-economic-crisis-the-plight-of-the-poor/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Jolliffe, Patricia, and Scott Foster. 2022. Different Reality? Generations’ and Religious Groups’ Views of Spirituality Policies in the Workplace. Journal of Business Ethics 181: 451–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailasapathy, Pavithra, and Jask Jayakody. 2017. Does Leadership Matter? Leadership Styles, Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviour and Work Interference with Family Conflict. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29: 3033–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, Bettina Kata, Lea Péter, Borbála Paksi, Zsolt Horváth, Katalin Felvinczi, Andrea Eisinger, Mark Griffiths, Andrea Czakó, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Bálint Andó. 2023. Religious Status and Addictive Behaviors: Exploring Patterns of Use and Psychological Proneness. Comprehensive Psychiatry 127: 152418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenyhercz, Viktória, Barbara Mervó, Noémi Lehel, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Bernadette Kun. 2024. Work Addiction and Social Functioning: A Systematic Review and Five Meta-Analyses. PLoS ONE 19: e0303563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kun, Bernadette, Dardana Fetahu, Barbara Mervo, Anna Magi, Andrea Eisinger, Borbala Paksi, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2023. Work Addiction and Stimulant Use: Latent Profile Analysis in a Representative Population Study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 23: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lace, John W., Kristen A. Haeberlein, and Paul J. Handal. 2018. Religious Integration and Psychological Distress: Different Patterns in Emerging Adult Males and Females. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 2378–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, Frederick, Jason Huang, and Stanton Mak. 2013. Protestant Work Ethic, Confucian Values, and Work-Related Attitudes in Singapore. Journal of Career Assessment 22: 304–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Roderick J. A. 1988. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83: 1198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, Kate, Andrew Macleod, and Marco Cinnirella. 2002. Are Women More Religious than Men? Gender Differences in Religious Activity among Different Religious Groups in the UK. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, William J. 2021. Buddha on Politics, Economics and Statecraft. In A Buddhist Approach to International Relations: Radical Interdependence. Edited by William J. Long. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriac, John P., David J. Woehr, and Christina Banister. 2010. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: An Examination of Measurement Equivalence across Three Cohorts. Journal of Business and Psychology 25: 315–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkevičiūtė, Modesta, and Aukse Endriulaitiene. 2023. Defining the Border between Workaholism and Work Addiction: Systematic Review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 21: 2813–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalewicz, Jacek, Barbara Badora, Michał Feliksiak, Antoni Głowacki, Magdalena Gwiazda, Marcin Herrmann, Ilona Kawalec, and Beata Roguska. 2019. Oszacowanie Rozpowszechnienia Oraz Identyfikacja Czynników Ryzyka i Czynników Chroniących Hazardu i Innych Uzależnień Behawioralnych–Edycja 2018/2019. Polish Ministry of Health. Available online: https://www.kbpn.gov.pl/portal?id=15&res_id=9249205 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Moskalewicz, Jacek, Barbara Badora, Michał Feliksiak, Magdalena Gwiazda, Ilona Kawalec, Małgorzata Omyła-Rudzka, Beata Roguska, and Jonathan Scovil. 2024. Oszacowanie Rozpowszechnienia Oraz Identyfikacja Czynników Ryzyka i Czynników Chroniących Hazardu i Innych Uzależnień Behawioralnych—Edycja 2023/2024 [Estimation of Prevalence and Identification of Risk and Protective Factors for Gambling and Other Behavioral Addictions—2023/2024 Edition]. Krajowe Centrum Przeciwdziałania Uzależnieniom. Available online: https://kcpu.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Hazard_2024_raport_FIN_wersja-poprawiona2-1.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu, and Bhikkhu Bodhi, trans. 2005. Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta. In The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. Available online: https://wisdomexperience.org/product/middle-length-discourses-buddha (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Page, Sarah J., and Andrew Yip. 2017. Understanding Young Buddhists: Living out Ethical Journeys. Leiden, Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. The Age Gap in Religion Around the World. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/06/13/the-age-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Porche, Michelle V., Lisa R. Fortuna, Amy Wachholtz, and Rosalie Torres Stone. 2015. Distal and Proximal Religiosity as Protective Factors for Adolescent and Emerging Adult Alcohol Use. Religions 6: 365–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rāhula, Walpola. 1967. What the Buddha Taught. London: Gordon Fraser Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Reid-Arndt, Stephanie A., Marian L. Smith, Dong Pil Yoon, and Brick Johnstone. 2011. Gender Differences in Spiritual Experiences, Religious Practices, and Congregational Support for Individuals with Significant Health Conditions. Journal of Religion, Disability & Health 15: 175–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, Baljinder Kaur, Phillip R. Shaver, and Kirk Warren Brown. 2010. A Scale to Measure Nonattachment: Buddhist Complement to Western Research on Attachment and Adaptive Functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment 92: 116–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroth, Holly. 2019. Are You Ready for Gen Z in the Workplace? California Management Review 61: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, Martin. 2024. Work Motivation Is Not Generational but Depends on Age and Period. Journal of Business and Psychology 39: 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, Howard J., Debi A. LaPlante, Richard A. LaBrie, Rachel C. Kidman, Anthony N. Donato, and Michael V. Stanton. 2004. Toward a Syndrome Model of Addiction: Multiple Expressions, Common Etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 12: 367–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonin, Edo, William Van Gordon, and Mark D. Griffiths. 2016. Ontological Addiction: Classification, Etiology, and Treatment. Mindfulness 7: 660–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriweera, W. I. 2014. Facets of Social and Economic History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Dayawansa Jayakody & Company. Available online: https://www.dayawansajayakody.com/books/facts-of-social-and-economic-history-of-sri-lanka (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Sørensen, Jane Brandt, Flemming Konradsen, Thilini Agampodi, Birgitte Refslund Sørensen, Melissa Pearson, Sisira Siribaddana, and Thilde Rheinländer. 2020. A Qualitative Exploration of Rural and Semi-Urban Sri Lankan Men’s Alcohol Consumption. Global Public Health 15: 678–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroope, Samuel, Blake Victor Kent, Ying Zhang, Namratha R. Kandula, Alka M. Kanaya, and Alexandra E. Shields. 2020. Self-Rated Religiosity/Spirituality and Four Health Outcomes among US South Asians: Findings from the Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 165–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, Steve, Nadra Lisha, and Mark Griffiths. 2011. Prevalence of the Addictions: A Problem of the Majority or the Minority? Evaluation & the Health Professions 34: 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Thomas Li-Ping. 1993. A Factor Analytic Study of the Protestant Work Ethic. The Journal of Social Psychology 133: 109–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M. 2010. A Review of the Empirical Evidence on Generational Differences in Work Attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology 25: 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer Sanchez, Zila, Lucio Garcia De Oliveira, and Solange Aparecida Nappo. 2008. Religiosity as a Protective Factor against the Use of Drugs. Substance Use & Misuse 43: 1476–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, Max. 1930. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz, Katie, Sarah Bowen, Erin Harrop, Haley Carroll, Matthew Enkema, and Carly Sedgwick. 2014. Mindfulness-Based Treatment to Prevent Addictive Behavior Relapse: Theoretical Models and Hypothesized Mechanisms of Change. Substance Use & Misuse 49: 513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2019. Burn-out an ‘Occupational Phenomenon’. International Classification of Diseases. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Yeung, Gustav K. K., and Wai-yin Chow. 2010. ‘To Take up Your Own Responsibility’: The Religiosity of Buddhist Adolescents in Hong Kong. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 15: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, Jerf W. K., Yuk-chung Chan, and Boris L. K. Lee. 2009. Youth Religiosity and Substance Use: A Meta-Analysis from 1995–2007. Psychological Reports 105: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabel, Keith L., Benjamin B. J. Biermeier-Hanson, Boris B. Baltes, Becky J. Early, and Agnieszka Shepard. 2017. Generational Differences in Work Ethic: Fact or Fiction? Journal of Business and Psychology 32: 301–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Zachary, Carol Jagger, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Mary Beth Ofstedal, Florencia Rojo, and Yasuhiko Saito. 2016. Spirituality, Religiosity, Aging and Health in Global Perspective: A Review. SSM—Population Health 2: 373–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda S. Cole, Mark S. Rye, Eric M. Butter, Timothy G. Belavich, Kathleen M. Hipp, Allie B. Scott, and Jill L. Kadar. 1997. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 117 | 66.5 |

| Man | 59 | 33.5 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school | 1 | 0.6 |

| Up to the ordinary levels (O/Ls) | 0 | 0.0 |

| Up to the advanced levels (A/Ls) | 8 | 4.5 |

| Vocational | 6 | 3.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 59 | 33.5 |

| Master’s degree | 44 | 25.0 |

| Doctoral degree | 58 | 33.0 |

| Monthly income before tax | ||

| LKR 22,500–29,999 | 0 | 0.0 |

| LKR 30,000–49,999 | 1 | 0.6 |

| LKR 50,000–69,999 | 12 | 6.8 |

| LKR 70,000–99,999 | 11 | 6.3 |

| LKR 100,000–199,999 | 50 | 28.4 |

| LKR 200,000–299,999 | 40 | 22.7 |

| LKR 300,000 or more | 56 | 31.8 |

| N/A | 6 | 3.4 |

| Managerial position | ||

| No | 60 | 34.1 |

| Lower | 14 | 8.0 |

| Middle | 55 | 31.2 |

| Top | 47 | 26.7 |

| Variable | M (SD) | Range | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work addiction (IWAS-7) | 16.39 (5.34) | 7–35 | – | |||||||

| 2. Work addiction (IWAS-5) | 12.14 (4.18) | 5–25 | 0.96 *** | – | ||||||

| 3. Religiosity | 4.55 (1.45) | 1–7 | 0.01 | −0.01 | – | |||||

| 4. Gender | 66.5% a | – | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.12 | – | ||||

| 5. Age (in years) | 41.84 (9.02) | 23–62 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.20 ** | 0.03 | – | |||

| 6. Education level | 91.5% a | – | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.15 * | 0.06 | 0.07 | – | ||

| 7. Monthly income | 82.9% a | – | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.21 ** | 0.39 *** | 0.41 *** | – | |

| 8. Managerial position | 65.9% a | – | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.25 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.08 | 0.41 *** | – |

| Predictors | Dependent Variable: Work Addiction (IWAS-7) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | 95% CI | t | |

| Moderating effect of gender | ||||

| Religiosity | −0.47 | 0.38 | −1.209; 0.274 | −1.25 |

| Gender | −0.54 | 0.90 | −2.324; 1.239 | −0.60 |

| Interaction: Religiosity × Gender | 1.01 | 0.59 | −0.165; 2.184 | 1.70 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.049; 0.152 | 1.01 |

| Education level | 0.56 | 0.40 | −0.240; 1.353 | 1.38 |

| Income | −0.55 | 0.43 | −1.396; 0.303 | −1.27 |

| Managerial position | 0.17 | 0.38 | −0.587; 0.922 | 0.44 |

| R = 0.181; R2 = 0.033 | ||||

| Moderating effect of age | ||||

| Religiosity | 0.08 | 0.29 | −0.500; 0.654 | 0.26 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.048; 0.150 | 1.03 |

| Interaction: Religiosity × Age | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.029; 0.150 | 2.90 ** |

| Gender | −0.29 | 0.89 | −2.057; 1.472 | −0.33 |

| Education level | 0.56 | 0.39 | −0.223; 1.334 | 1.41 |

| Income | −0.52 | 0.42 | −1.357; 0.310 | −1.24 |

| Managerial position | −0.05 | 0.38 | −0.790; 0.699 | −0.12 |

| R = 0.251, R2 = 0.063 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Zoysa, P.; Charzyńska, E.; Bochniarz, K.T.; Atroszko, P.A. Work Addiction in a Buddhist Population from a Buddhist-Majority Country: A Report from Sri Lanka. Religions 2025, 16, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080944

de Zoysa P, Charzyńska E, Bochniarz KT, Atroszko PA. Work Addiction in a Buddhist Population from a Buddhist-Majority Country: A Report from Sri Lanka. Religions. 2025; 16(8):944. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080944

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Zoysa, Piyanjali, Edyta Charzyńska, Klaudia T. Bochniarz, and Paweł A. Atroszko. 2025. "Work Addiction in a Buddhist Population from a Buddhist-Majority Country: A Report from Sri Lanka" Religions 16, no. 8: 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080944

APA Stylede Zoysa, P., Charzyńska, E., Bochniarz, K. T., & Atroszko, P. A. (2025). Work Addiction in a Buddhist Population from a Buddhist-Majority Country: A Report from Sri Lanka. Religions, 16(8), 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080944