1. Introduction

In Pentecostal discourse, socio-ethical thinking is either dissociated from theology or regarded as non-existent. Pentecostal praxis is limited to the workings of the Holy Spirit in evangelism, exorcism, laying of hands, and prayer. The praxis of social concerns is viewed as conflicting with the Pentecostal theology and missional ethos. These conflicting theorists, or outsiders, to use Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen’s word, think that premillennial eschatology, as the driver of a missional agenda fueled by the urgency of soul-winning and the imminent return of Jesus Christ, negates any form of socially orientated ministry (

Kärkkäinen 2014, p. 170). The ‘progressives’, on the other hand, report that the same theology that drives mission includes social ministry as a component of holistic mission (

Ma and Ma 2020;

Ma 2015;

Hunter 2014;

A. H. Anderson 2020;

Miller 2009;

Miller and Yamamori 2007). The term progressives used by Miller and Yamamori describes Pentecostals’ ‘response to a holistic understanding of the Christian faith, hinged on their belief in the spirit world, holistic view of the person and sensitivity to the social reality of their context’ (

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 25).

Debates on the socio-ethical thinking among Pentecostals are focused on the view that the otherworldly mindset produced by eschatological thinking among the Pentecostals turns their attention to going to heaven and consigning the earth to apocalyptic annihilation. However, a contrary view is that early Pentecostal missionaries included schools, hospitals, and empowerment programmes in their missional agenda (

Ma 2015). An example is the theologically hinged ethical argument that draws a similarity between Pentecostals and the nexus between economic poverty and spiritual prosperity that invoked the Weberian genealogical proposition known as the ‘Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’ (

Nogueira-Godsey 2012). Against the impression that Pentecostals are not involved in development, the argument is that the NGO-ization of missions grew from Pentecostal groups funding development programmes through sodalities such as NGOs (

Freeman 2012). Alan Anderson has summarized the political involvement of Pentecostals in Latin America, South Africa, East Africa, and West Africa as a unique turning point in the social orientation of Pentecostals to harmonize personal and societal transformation in their mission (

A. Anderson 2012).

In Nigeria, Pentecostalism is the dominant stream of evangelical Christianity that began establishing itself in the 1850s through the efforts of Western missionaries, ex-slaves, and native people (

Peel 2003). In 1888, native churches started to emerge in Lagos, challenging the colonization of worship and leadership by Westerners (

Webster 1964). By the 1920s, these contestations led to the growth of independent churches with a focus on addressing African issues and indigenizing worship and leadership. These independent churches, collectively known as African Indigenous or Indigenous Churches (AICs), included prophetic and apostolic movements. One of the prophetic churches was the Cherubim and Seraphim Church (C&S), founded by Moses Orimolade in 1927 (

B. C. Ray 1993).

Christ Apostolic Church emerged from the apostolic stream of the 1920s, displaying pneumatological expressions characteristic of global Pentecostalism. More Pentecostal-orientated Nigerian churches emerged in the 1950s and 1970s, either from mission-founded churches or AICs. A notable example is the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), which originated from the Cherubim and Seraphim Church (C&S) in Ebute Meta, Lagos. Josiah Akindayomi, a former C&S prophet, founded RCCG in 1952 with a narrative of both continuity and divergence from some Aladura practices (

Ukah 2008). He led the church until his death on 2 November 1980. RCCG’s remarkable growth as a neo-Pentecostal mega church in Nigeria from the 1970s to the 1990s is linked to the Pentecostal revival that swept Nigeria’s tertiary institutions during this period, its elite membership, and the charismatic leadership of Dr. Enoch Adeboye as Akindayomi’s successor.

The emergence of Adeboye on 10 January 1981 set the stage for a series of internal reforms that propelled RCCG into prominence. From Akindayomi’s initial 40 parishes located within Yoruba cities in Southwestern Nigeria (

Adeboye 2007,

2012;

Ukah 2008), RCCG has become a global phenomenon due to Adeboye’s modernizing strategies, which included establishing a two-tier church structure comprising model parishes alongside traditional classical parishes, reconceptualizing social vision as Christian Social Responsibility (CSR) (

Adeboye 2007,

2012;

Ukah 2008) and fostering a camp spirituality reflecting a reconfiguration of inherited Aladura practices. According to its official sources, CSR is motivated by the love of God and aims to impact communities and individuals. It is envisioned “to be the global model for meeting the ever-evolving socio-economic needs through its hubs, brands, and sub-brands” (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., p. 6). This vision is implemented through eight channels: Social, Health, Education, Media, Business, Arts, Governance, and Sports, collectively known as SHEMBAGS (see

Figure 1).

Based on the literature sources and data from fieldwork undertaken between 2019 and 2022 as part of doctoral research, this paper will affirm that African Pentecostals espouse a context-shaped social orientation. A significant member of this family is RCCG with a worldwide social and evangelistic impact (

A. Anderson 2012;

Ukah 2008;

Adogame 2007;

Hunt 2002;

Oguntoyinbo-Atere 2009;

Burgess et al. 2010;

Akhazemea and Adedibu 2011). Its headquarters is located in the Redemption City in Mowe along the Ogun State section of the Lagos–Ibadan Expressway in Southwestern Nigeria. Due to conurbation and its proximity to Lagos, Mowe is loosely referred to as an extension of Lagos.

Nigeria, the RCCG’s socio-economic context, is Africa’s largest economy despite its poverty index, underdevelopment, and paucity of critical infrastructures. Based on multiple sources, Nigeria’s underdevelopment is causally linked to individual poverty. According to

World Economic Forum in 2019, six Nigerians fall into poverty every minute (

Weforum.org 2020). In 2020, the

World Poverty Clock, an international research agency into global poverty, presented the statistics this way: at the poverty threshold of USD 1/day, 93,842,875 of 196,842,992 Nigerians lived in extreme poverty in 2019, out of which 63 per cent were rural dwellers and 35 per cent lived in urban centres. The genders share 48 per cent apiece. The forecast for 2020 is a gloomy one, with Nigeria contributing 95,903,776 of the 597,789,776 world’s impoverished people

Worlddata.io (

2020). According to the World Bank’s Nigeria Development Update (NDU) released in October 2024, “Poverty is high and rising in Nigeria”. In May 2025, the same NDU called upon Nigeria to reduce poverty and foster shared prosperity (

World Bank 2025). For political and prebendal motives, these figures are always contested by the nation’s government. However, the reality of poverty in Nigeria is ingrained in all forms of criminal activities, including cultic practices of ritual killings.

This is the socio-economic milieu that inspired CSR as a social practice to challenge this “decadence” in society. CSR also stands as a counter narrative to the idea that Pentecostal leaders are also blamed for the socio-economic disequilibrium that makes them richer pastors of poor members. CSR also draws a connection between the vibrancy of Christianity and deepening poverty in Nigeria. Therefore, this study aspires to analyze RCCG’s social practice, formally termed Christian Social Responsibility (CSR).

This paper begins with an analytical description of Nigeria’s socio-economic context. This analysis will be followed by a critique of CSR by situating it within a global Pentecostal context. In the end, CSR is presented as a critique of the lopsided notion that African Pentecostals focus only on self-enrichment. It concludes that CSR, and indeed any social intervention programmes, cannot end poverty without a national poverty alleviation policy.

2. The RCCG and the Vision for the Transformation of Nigeria

Beginning with the machinery that drives CSR in RCCG, this section provides a historical background of the social practice of the RCCG and its vision to transform Nigeria. The first machinery is the power structure, headed by Enoch Adeboye as the General Overseer (GO), assisted by Assistant General Overseers (AGOs), a National Overseer (NO), and Special Assistants (SATGOs). The second machinery is the administrative structure, comprising the central administration and the parish system, which is under the oversight of the GO and his wife, Folu Adeboye, as the mother in Israel.

The central administrative office, located at the global headquarters in the Redemption Camp, is headed by an AGO responsible for administration and personnel. Administrative council meetings are coordinated by the NO with the AGO acting as secretary. Decisions from these meetings are forwarded to the GO as the chair and convener of the Church Council. All decisions from the international offices abroad, the boards, and the NO are subject to ratification by the Council.

The parish system is a 5-tier pyramidal structure, with the local congregation at the base. Local parishes are led by pastors who are, in turn, coordinated by an area pastor as the head of parishes within an area. Zonal pastors are higher in hierarchy and oversee the areas. Above the zonal pastors is the pastor in charge of that province. Provincial pastors collectively report to the regional pastor who in turn reports to an AGO. An overlap in roles results in multiple responsibilities and titles for some individuals; for example, a parish pastor could also be in charge of a province and serve as a Special Assistant to the General Overseer (SATGO) or AGO. Overall, the GO is the ultimate decision-maker, with his wife, Pastor Mrs Folu Adeboye, positioned above the AGOs but below the GO in the church’s power hierarchy.

The parish system also produced the internal CSR system, which is concentrated at each provincial level. Under the administration of a Special Assistant to the General Overseer (SATGO) on CSR, a province collects the CSR contributions from the parishes and forwards them to the central CSR secretariat, currently located in Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria. CSR is “the faith-based expression of social responsibility.” It is also a Christian concept by which the church “is meant to be an example for the world to follow, rather than the other way round.” Through CSR, this social vision was designed to “impact communities and individuals through love expression” (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., pp. 3, 6).

The CSR vision is delivered through six channels, namely: the eradication of illiteracy in Nigeria by 2025 (

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d., p. 12), the establishment of food banks and feeding centres (

RCCG-CSR Operations n.d., p. 5) to feed at least 2 million people per week (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., p. 20), empowering inmates in prison and orphanages, the provision of funds and infrastructures to schools and pupils, providing free medical checkups through medical centres established in rural areas, and the provision of clothes and clothing materials through its Charity Shops (

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d., p. 18). Moreover, CSR was envisioned ‘To be the global model for meeting the ever-evolving socio-economic needs through its hubs, brands, and sub-brands’ (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., p. 6).

To pursue these objectives, the CSR Secretariat has designed two working documents, known as the Policy Document, hereinafter referred to as the ‘Policy’, and the Operations Manual, hereinafter referred to as the ‘Manual’. Two other materials published by the CSR office include a book by Idowu Iluyomade titled

CSR: A Matter of Life and Death? and the CSR Newsletter called the

CSR Chronicles. The Policy has 29 pages, which “sets the standard for CSR initiation, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation”. It also explains that the responsibility of the office of the Special Assistant to the General Overseer (SATGO) for CSR is to coordinate all CSR programmes, harmonize them for impact, standardize CSR practice, and maintain communication across the church’s platforms, public channels, and forums (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., p. 3). The following section shows that social practices began in RCCG before the creation of these documents and structures and before CSR as its nomenclature.

2.1. The Social Practices of Josiah Akindayomi

Members of the RCCG would argue that social practice began in the RCCG before it was termed CSR. This view lay the foundation for what is known as CSR today in the 1950s, when its late founder routinely offered food to members. According to Bolarinwa, a prominent pastor and beneficiary of RCCG social practice, Akindayomi later added water as a gesture of hospitality to all members and visitors to the church premises and programmes. By making food and water its foundation of social concern, RCCG mirrored the social projects of early Christian missions, which were motivated by the care for the poor and expression of Christian love (

Peel 2003). The same motivation drove the establishment of maternity and health services adopted as part of the RCCG social vision.

According to the historian Olufunke Adeboye, “In the early days of the mission under Pa Josiah Akindayomi, a maternity had been established at Ebute Metta to serve not just RCCG members but also the immediate community” (

Adeboye 2017, p. 323). Establishing a birthing centre was a common practice within

Aladura churches as they sought to counter the perceived demonic root of infant mortality (

Ogunjuyigbe 2004, p. 51). For example, Christ Apostolic Church (CAC), a major Aladura church in Nigeria, established birthing centres to discount the conventional health system and resort to a more “radical and liberating belief” in prayer to curb the influence of spirits on normal human activities (

Peel 1968, p. 119).

2.2. The Philanthropic Activities of Model Parishes

The second expression of social vision in RCCG began with the philanthropy of wealthy elite members of the newly created model parishes of RCCG. In 1988, Adeboye introduced a significant reform by forming two ecclesial structures known as both ‘model’ and ‘classical’ parishes. The classical parishes were headquartered in the 40 parishes left behind by its founder, Akindayomi. They also reflected the initial holiness ethos and piety of the founder. The model parishes, on the other hand, were spread across the Lagos urban geo-economic axis of Ikeja (the seat of power), Apapa (the centre of commerce), Victoria Island (the business hub with the largest concentration of multinationals), and Gbagada (a sprawling cosmopolitan city that connects these centres with the newly developing suburban residential part of Lagos).

Moreover, these model parishes were designed to accommodate the modernity and liberalism that tempered the strict pietism of Akindayomi, paving the way for the rise of the new elites that transformed RCCG into an alternative social force within Nigerian society (

Ukah 2008). They also reflected and accommodated the trending pattern of contemporary Pentecostalism in Nigeria by embracing the flexibility of worship and teachings that emphasized prosperity and motivational sermons. Furthermore, model parishes served economic ends by attracting social and high-net-worth individuals, many of whom were CEOs of transnational companies. Most of those individuals who eventually emerged as pastors within new parishes sought to legitimize their positions and influence by combining charity with spirituality (

Ukah 2008, p. 113). One such individual is Idowu Iluyomade, who until recently was the pastor of RCCG City of David Parish, Victoria Island, Lagos, head of the association of RCCG churches known as the Apapa family, and the pastor in charge of Region 20.

2.3. Social Vision and CSR Structure

The researcher discovered that the current CSR structure did not emerge until 2017 when Pastor Adeboye established the dissolved CSR Steering Committee. The CSR Steering Committee was led by Bayo Olugbemi under the supervision of Johnson Osuolale Odesola, the erstwhile AGO in charge of administration. Bayo Olugbemi, a stockbroker and the pastor in charge of Province 21 and Victory Parish of RCCG, was mandated to galvanize the disparate social ministry efforts that members of the Apapa family had created from the dissolved model parishes and other volunteers within RCCG.

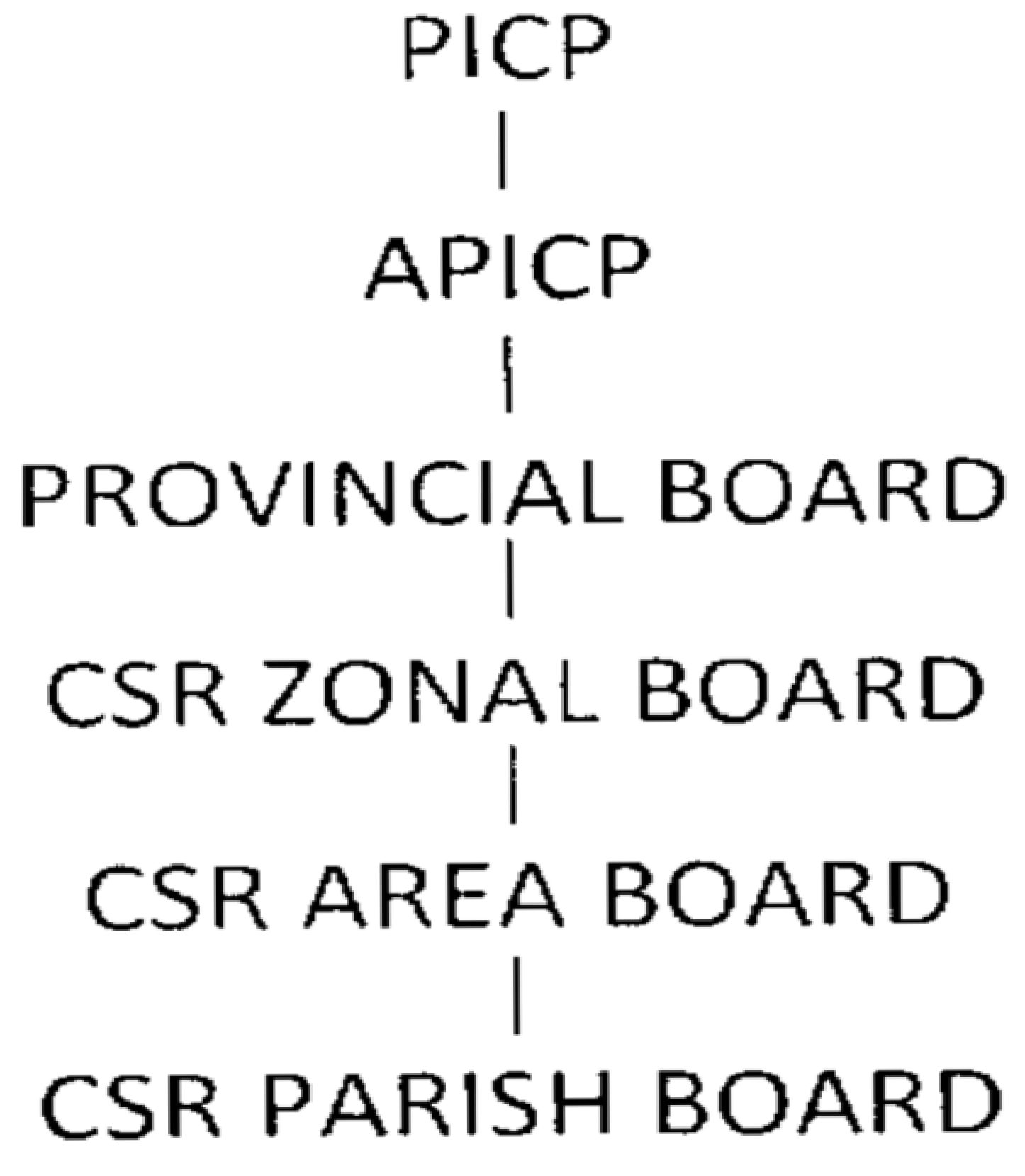

Between 2017 and 2018, the Steering Committee expanded the social practice of the RCCG beyond the Apapa family to include other emerging cosmopolitan provinces located mainly in the highbrow areas of Lagos, comprising Ikeja, Gbagada, Ikoyi, Lekki, and Victoria Island. These provinces are currently known as Lagos Province 1, 21, and 23. The Steering Committee paved the way for the creation of the current global CSR structure coordinated by the SATGO for CSR. As shown in

Figure 2, the provinces are retained as the strategic units in RCCG administration and CSR practices. Each province has an Assistant Pastor in charge of CSR (APICP-CSR) to coordinate CSR activities and fundraising within that province and report to the SATGO.

Between January and March 2028, the CSR committee consolidated its operations by establishing a CSR secretariat led by a chief operations officer, who reports to Idowu Iluyomade as the first SATGO-CSR. It could be observed that the appointment of Iluyomade as the SATGO legitimized his influence and that of his Apapa family members, who provided resources and led their congregations to justify the position they held. As the current global coordinator of CSR (SATGO-CSR), Iluyomade seamlessly merged the existing CSR structure of his parish, RCCG City of David Parish, with the dissolved steering committee of Bayo Olugbemi. To give a global secular appeal to this new governing structure, the name His Love Foundation was adopted for it.

Therefore, the global headquarters for His Love Foundation is the former CSR secretariat of RCCG City of David Parish, located at Oniru Street, Victoria Island. The office is located in the same building, housing two CSR facilities, His Stripes Hospital and a charity shop. The chief operations officer, Detola Akinremi, oversees these offices and other CSR operations. Funds from the parishes are reserved in the CSR Central Remittance Portal in the CSR global headquarters, administered by the SATGO, with the approval of the general overseer, Enoch Adeboye.

In summary, CSR operations are coordinated by a bureaucratic structure that emerged as part of the routinization process, giving Adeboye the rational, legal, and traditional forms of authority over the social practice of the Apapa Family and the other members of the CSR committee. CSR funding is not drawn from the main RCCG finances but rather from the altruistic giving of individuals, corporate organizations, and congregations. By galvanizing individual and corporate philanthropies, RCCG has strengthened its social practices, driven by the aristocratic structure headed by the GO and his wife.

3. Christian Social Responsibility in Practice

The RCCG grounds its social practice in the sayings of Jesus reflected in Matthew 25:35–46, the inalienable role of social ministry in evangelization (

The Good Samaritan 2017, p. 5), and the observable decadence in society (

The Good Samaritan 2017, p. 9). The same account is told in Luke 10:30–34, to illustrate the supremacy of love over the racial, religious, and cultural biases that existed between Jews and Samaritans in the days of Jesus’s earthly ministry. For RCCG, CSR is a channel for demonstrating this love by responding to both social and evangelistic needs within its milieu and complementing the social activities of government and its agencies (

The Good Samaritan 2017). It states further that its CSR aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This way, RCCG claims to give CSR a global orientation by joining many others that draw a link between CSR and the SDGs. RCCG’s understanding of Nigeria’s socio-economic malaise demonstrates its local rootedness and the awareness of Nigeria’s peculiar contradiction as a wealthy nation of poor people. CSR practice is channelled through what RCCG has combined into SHEMBAGS, an acronym for Social, Health, Education, Media, Business, Arts and Culture, Governance, and Sports. The following sections will analyze these channels of social practice.

3.1. Social Ministry, Rehabilitation, and Feeding Programmes

Social ministry, comprising help to needy, vulnerable, and poor people, involves long-term rehabilitation and short-term interventions. Long-term rehabilitation involved the building of social institutions as correctional and empowerment centres such as a rehabilitation facility, known as the Wholistic Ministry, located in Loburo, a sleepy community some 20 km from the Redemption Camp in Mowe, Ogun State, in Southwestern Nigeria. This facility was established in 2002 by Mrs. Folu Adeboye. The two arms of this facility are the outreach/rehabilitation and the preventive services arm. The outreach arm is charged with rescuing, recovering, and rehabilitating women from prostitution, forced labour, and human trafficking. The preventive arm offers a training platform to churches and others on how to aid vulnerable girls. In this case, vulnerable is used to describe women in prostitution, those rescued from sex trafficking or other forms of sexual and emotional abuse, and victims of homelessness.

Within the perimeter of the

Wholistic Ministry is another rehabilitation centre known as the

Habitation of Hope, established in 2006 and run by Mrs Adeboye. It is a facility that provides accommodation, health care, and education to boys between the ages of 7 and 18 years who are deprived, destitute, and homeless. This Habitation of Hope has transformed about 6976 boys since its inception (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 8). Christ Against Drug Abuse Ministry (CADAM) is another rehabilitation centre established in 1991 as the Drug Addicts Rehabilitation Ministry by the Ladipo Oluwole Parish of RCCG in Ikeja. The recent expansion of the facility, coupled with its renaming as the Folu and Enoch Adeboye Rehabilitation Centre in 2017, makes CADAM one of Mrs Adeboye’s social ministry projects (

The Good Samaritan 2017, p. 16). CADAM has offered spiritual therapy, life skills, psychological therapy, and vocational skills to 2805 drug and substance abuse victims since its inception (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 8).

CSR social programmes include feeding members and non-members by upgrading the inherited food programme with school feeding programmes, prison food programmes, and international food aid to victims of disasters. On the international scene, the RCCG claims to have donated to victims of natural disasters in Africa and Asia. It distributed foodstuffs to 1000 victims of the Super Typhoon at Calasiao, Pangasinan, Philippines. RCCG’s Mercy Ship berths in the neighbouring Benin Republic and functions as the conveyor of relief materials in times of need (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 6). According to Iluyomade, ‘Right now, we feed 60,000 people in Lagos every Sunday’ (

Odesola 2017, p. 11). RCCG claims to have donated NGN one hundred million towards the relief of the Internally Displaced People (IDP) of Northeastern Nigeria (

Odesola 2017, p. 8).

The CSR Chronicles claims that between March and December 2018, it fed 200,000 people in nine centres in Lagos alone and nine million people in 42,821 parishes in Nigeria. This is in addition to 5000 prison inmates fed every Sunday in Lagos alone (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 6).

CSR policy sees “Hunger as a leveler cuts across religion, race, age, and creed. A hungry man cannot shout Hallelujah. We have a clear, unambiguous directive from the General Overseer of the RCCG that all parishes must be involved in feeding as a strategic tool for Church growth and societal impact” (

RCCG-CSR Policy n.d., p. 20). A research visit in May 2019 witnessed the feeding programme by RCCG Victory Parish in Magodo, Lagos. This feeding outreach focused on the homeless in the Ketu area of Kosofe Local Council in Lagos state. Though this feeding programme was without religious discrimination, it popularized RCCG among the beneficiaries.

3.2. Health and Well-Being

The health care channel of CSR is two-pronged; firstly, it involves collaborating with government health care facilities, and secondly, it involves establishing health care institutions. For example, RCCG’s partnership with the Lagos University Teaching Hospital in Ikeja involved the donation of an Intensive Care Unit in 2017. A similar gesture was extended to the Plateau State Government-owned Jos Specialist Hospital in May 2019 by the CSR office of RCCG (

The Good Samaritan 2017, p. 8). At the Kirikiri Maximum Prison in Lagos, Nigeria, RCCG donated a health centre that replaced the government-owned cottage hospital. During the COVID-19 battle, RCCG was also one of the churches that contributed to the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria.

The second dimension to be highlighted shortly is the direct provision of health care by establishing health care centres on at least Victoria Island and the Redemption Camp, in Lagos. The researcher also visited an RCCG health facility known as His Stripes Hospital in Victoria Island, Lagos, which is within the premises of the CSR Secretariat in Lagos, located on Alaba Oniru Way in Victoria Island Extension. The facility is emblematic of the RCCG health ministry, and conveys its understanding of health as the holistic well-being of the individual and a strategic CSR component (

The Good Samaritan 2016). According to RCCG, ‘Every dialysis session is highly subsidized, with a good number done for free’ (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 7).

As part of its vision for holistic well-being, RCCG has undertaken the provision of water to rural communities. During an observation research visit in May 2019, a borehole water project sponsored by the RCCG Province 23 was donated to Isale Ira, a fringe community off the major Ikeja urban road, off Yaya Abatan, up to the end of Ajayi Road in Lagos, by RCCG Province 23, with headquarters in Maranatha Parish, Gbagada. Lagos. A water borehole is a narrow hole drilled into the soil manually or mechanically to draw underground water to the surface, utilizing either an electric pump or a manually operated lever.

3.3. Education and Skill Acquisition as CSR

In the area of education, CSR activities are implemented in four dimensions. First, there is the building of schools in rural and suburban communities to offer free education to members of such communities. Examples of such schools are Redeemer’s Fortress School, Umu-Obi Awkuzu, in Anambra State, and Hope Centre Makoko in Lagos State. There is also the Redeemer’s Nursery and Primary School, Oko Abe, and The Redeemer’s Junior Secondary School, Ito-Omu. The Redeemer’s Senior Secondary School, Ito-Omu, and Liberty Schools were established in 2014 to provide free education for the People of Maryland and the Ajah Community (

The CSR Chronicle 2018, p. 6).

A second form of educational empowerment involves providing funds to prison inmates to study and take examinations. The Christ Redeemer’s Welfare Scheme is responsible for processing and disbursing educational grants and bursaries to assist students in completing their education. According to Odesola, 1000 students benefited from its welfare scheme in 2015 alone (

Odesola 2017, p. 7). The second aspect of educational development is the establishment of fee-paying urban schools grouped as the Redeemers Group of Schools. The third type of educational institution is the tertiary form, comprising Redeemers University, Ede, and Redeemers School of Management in Mowe. RCCG claims that these institutions are the church’s transforming activities that nurture and empower the individual (

Iluyomade 2018;

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d.;

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d.).

The fourth aspect of educational service is in the form of grants, aids, scholarships, and endowments. These include over 100,613 scholarships and grants to students at the Universities of Nsukka, Ibadan, Ile-Ife, and Lagos. There is evidence that in 1988, Adeboye established the Redemption Christian Fellowship (RCF) in these campuses. Some beneficiaries of CSR grants and others converted through RCF outreach to tertiary institutions later formed the church’s workforce. They constitute the upwardly mobile and articulate individuals who invest their energy and time in church programmes and were instrumental in the opening of many RCCG parishes overseas (

Ukah 2008).

3.4. Media as a Channel of Social Responsibility

CSR activity through the

Media and

Communication channel is interpreted as the means to impart and exchange information toward education and persuasion, including public relations and performances (

Iluyomade 2018;

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d.;

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d.). Between 1980 and 1990, the RCCG introduced strategies that harnessed socio-economic and human resources to catalyze its growth and launched it globally by investing in Internet, radio, and television stations to propagate the Gospel and advertise its programmes. Two of the church’s television stations are Dove TV and the Redeemed Television Ministry (RTM). Its radio station is known as Lifeway Radio. Its media outfit, Dove Media, connects to satellite stations in other parts of the world like Dubai, Dallas, Johannesburg, and Lagos (

Iluyomade 2018;

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d.;

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d.).

3.5. Business and Entrepreneurship

Business and the

Economy are channels of CSR activity that provide an enabling environment to nurture the visions and dreams of business-savvy members. Business is interpreted as all activities carried out as a form of business transaction and resource management (

Iluyomade 2018;

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d.;

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d.). CSR businesses include Haggai Microfinance Bank, established by a group of RCCG members to provide the incentive and space for members to invest in the business. In an interview with Bayo Olugbemi, a founding shareholder of the Bank, it was revealed that Haggai belonged neither to Adeboye nor to RCCG.

CSR encourages skill acquisition as a means of poverty alleviation and for multiplying streams of income. In an interview with three beneficiaries of such a scheme funded partially by Victory Parish of RCCG in Magodo, Lagos, it was discovered that members of the church were regularly assisted to acquire additional skills regardless of gender, age or status. These beneficiaries claimed that the cost of training was paid by the church; they bore the cost of transportation to the training venue.

3.6. Governance and Politics Including Arts and Culture

RCCG engrafted ‘

Governance and

Politics’ as part of its praxis of CSR, by which it aspires to shape society. It interprets governance as influence, encouragement, and participation in the process of governance and politics (

Iluyomade 2018;

RCCG-CSR Operation Manual n.d.;

RCCG-CSR Policy Document n.d.). The church’s political imagination is better illustrated in the political career of two of its pastors, namely, Mrs Oluremi Tinubu and Yemi Osinbajo.

Before her ordination on 7 August 2018, as an assistant pastor, Mrs Tinubu was a prominent church member of the Nigerian senate and wife of Bola Ahmed Tinubu, a Muslim, former governor of Lagos State, and the current president of Nigeria. Mrs Tinubu’s status in RCCG sparked a debate about how a person with a Muslim spouse can function as a pastor.

Pastor Yemi Osinbajo, on the other hand, was the Vice President alongside Muhammadu Buhari, the President of Nigeria, from 2015 to 2023. Osinbajo was criticized by some Christians for being ‘unequally yoked’ to Buhari, a Muslim, by standing with him in politics. This notion is hinged on an interpretation of Paul’s warning in 2 Corinthians 6:14. A different school of thought is that Osinbajo is too weak to influence a change, which is reflected in his inability to stop the killing of Christians in the North of Nigeria. However, Osinbajo may also be seen as “the face of Pentecostalism in national politics” (

Ojewole and Ehioghae 2018, p. 328).

Regarding the political engagement of Pastor Adeboye before he emerged as the GO in 1980, he was one of Nigeria’s Christian voices against the government’s hosting of the FESTAC’77.

1 The festival was viewed as the importation of demonic influence into Nigeria (

Burgess 2015). Another instance was Adeboye’s confrontation with Sanni Abacha, the military junta that planned to kill him. The fulfilment of Adeboye’s prophecy about the demise of Abacha triggered considerable recognition that turned attention toward Adeboye (

Burgess 2015).

Overall, the CSR practice of altruistic giving negates the generalized view that Nigerian Pentecostal churches are distributing poverty to members through prosperity messages. For its contribution to arts and culture, CSR under the City of David Parish invested in film and drama series titles such as ‘Oasis’ and ‘Heaven’s Gate’. The church also claimed to sponsor local school sports as part of the CSR promotion of sports in Lagos. CSR activities are described as RCCG’s effort to transform Nigeria.

4. A Global Perspective on RCCG Social Practice

Pentecostalism lies at the intersection of promoting healing theology in Africa, consumerism in America, capitalism in Latin America, and individualism worldwide. Salvation as the start of personal transformation and prosperity is emphasized and personalized by Pentecostals. This idea also incorporates the belief that transformed individuals will change society. However, these paradigms of Pentecostal messages and practices have faced sociological critique. This section follows that trajectory by positioning CSR as RCCG’s vision for social change within the global Pentecostal discourse.

In

Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement by Tetsunao Yamamori and Donald Miller, the Weberian framework is deployed in characterizing the spirituality undergirding Pentecostal social practice. According to them, two dominant streams of global Pentecostal churches exist, namely, the progressives, known for their innerworldy ascetic lifestyle, who have social ministry as part of their practice; they are also characterized as “modern Pentecostals with their joyous but strict ethic, warm and ecstatic worship, open to the spiritual realm and spiritually disciplined”(

Miller and Yamamori 2007, pp. 171–72). And there are the rather polemically classified “legalistic otherworldly” type, whose ascetic lifestyle and eschatological view reflect the preaching of the salvation-only message (

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 32).

In their analysis, Miller and Yamamori framed progressive Pentecostals as Weberian Puritans and juxtaposed them with Max Weber’s Calvinist Protestants (

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 164). Max Weber’s

Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism claimed that socio-economic issues affected the transition of society to capitalism and modernity; he saw the emergence of capitalism as being linked to Calvin’s theological teaching on election. Weber’s theses are, first, that religious ideas influence social and economic organizations. Secondly, people’s beliefs are capable of producing social change as a way of making meaning of their religious and ideological world (

Weber 2008).

Similarly to Weber’s association of Calvinist Protestants with pietism and prosperity, Miller and Yamamori ascribe Pentecostal ascesis to the same end of prosperity. Following this framework, we proceed by arguing that RCCG altruistic giving is ascetic and a consequence of religious change. We also posit that the promise of a reward to members who give to CSR aligns with an innerworldly–otherworldly–this-worldly mindset that inspires giving regardless of whether Nigeria can be transformed or not.

4.1. RCCG, Pentecostal Ascetics, and Weberian Capitalism

Whether as salvation only or salvation and social practice, the Nigerian Pentecostal soteriology euphemistically known as “Born Again” incorporates an ascetic lifestyle. Ruth Marshall’s nuanced approach to the Born Again phenomenon is instructive in understanding the difference between Nigerian Pentecostalism and its Western streams (

Marshall 2009). The Born Again phenomenon, as preached in Nigeria, includes the disruption of all ties with the world and unconverted family and friends. It has produced an alternate community for members who want to escape the contamination that is the world, as evidence of individual transformation. The Born Again theology embraces (material) prosperity as evidence of (holy) spiritual prosperity, by which it hopes to create a new community of upwardly mobile “sanctified vessels” (

Chung 2007, p. 146).

RCCG follows this theology by promoting spirituality, prayer, and holiness, linking poverty to sinfulness, and offering salvation and holiness to assist members to adopt modest lifestyles necessary “to make heaven”. Donald Miller observes that this Pentecostal scheme is capable of propelling members socio-economically (

Miller 2009). Holiness, according to Miller and Yamamori, produces the self-discipline against bad behaviours that “give them a competitive advantage over their peers”(

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 161).

The argument is that behavioural transformation, instead of Calvinism, is the Pentecostals’ route to an ethic similar to Weber’s Protestant ethic (

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 165). Moreover, by acknowledging RCCG as an example of the ascetic-type progressive Pentecostal, its CSR and spirituality arguably align with Weber’s theory of the capitalist economy. As Joel Robbins noted, asceticism orchestrates mysticism, “which prepares individuals for the global capitalist economy”(

Robbins 2004, p. 131). Nolivos adds that Pentecostalism’s widespread appeal in Latin America is connected to this transformative ethos, which he argues is essential for the development of capitalism (

Nolivos 2012).

The Pentecostal interpretation of Weber’s theory, as described by Peter Berger, is presented as the Pentecostal Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Berger, similarly to Miller and Yamamori, interprets Weber’s concept of asceticism in light of Pentecostal ascetic tendencies. However, this debate has occurred within a neoliberal capitalist framework that evaluates how Pentecostalism’s material culture, messages, and practices promote consumerism, upward social mobility, and a bourgeois lifestyle.

The opinion is that RCCG and all Nigerian neo-Pentecostal churches constitute “contextual Pentecostal churches that appropriate the holistic gospel to local contexts by reflecting on contextual needs” (

Yong 2012, p. 17). This means that they share the core features of global Pentecostals that locate them at the intersection of the Weberian economy. For example, promoting individual socio-economic upward mobility through biblicism and prayer warfare is common in global Pentecostalism (

Robbins 2004, p. 122) and in the biblical and spiritual approach that challenges the overemphasis on theological orientation in the above context in Pentecostal social practice. Therefore, RCCG aligns with our view that accords with Matthias Deininger’s linkage of Pentecostal asceticism “to cosmic warfare, evangelism, and premillennial eschatology” (

Deininger 2014, p. 61). We conclude that, regardless of context, the Pentecostal message anywhere is capable of the paradox envisioned by Weber—one that propels members towards prosperity and precipitates the poverty of others.

4.2. Giving for Personal Reward and National Transformation

Weber’s theory has been further applied to Pentecostalism’s market-savvy culture in developing countries. According to Trad Nogueira-Godsey’s “Pentecostal Ethic of Development”, Pentecostals can offer a solution to the present economic problem in developing countries based on their innerworldly ascetic lifestyle (

Nogueira-Godsey 2012). This perspective resonates with the African idea of development that differs from the conventional idea of development theories that emerged in the 1980s, locating Pentecostals at the intersection of modernity and capitalism (

Jones 2015).

African Pentecostals spiritualize national development as a component of a political theology of redemption and proffer a solution to the spiritual cause of poverty as part of societal transformation. Ruth Marshall wonders why Nigerian Pentecostals, including RCCG, reflect on the history and evil of colonization in their prayers for national transformation but fail to colonize the same political space that promotes poverty in Nigeria (

Marshall 2009, p. 201). The point is that Nigerian Pentecostals acknowledge the presence of poverty but spiritualize it by prescribing fasting and prayer as solutions. They promote power encounters against the personal and territorial spirit of poverty through prayers and empowerment that overlook the structural cause of poverty. According to Ray, a development economist, structural poverty is the worst type of poverty there is (

D. Ray 1998).

RCCG has found correspondence in the interpretation of poverty’s spiritual and material causes by proffering biblical and social antidotes through teachings on God’s reward system based on obedience to the Bible. Though its CSR promises governance, and members are encouraged to hold political offices, RCCG has not gone far enough to challenge Miller and Yamamori’s view that “it is difficult even for mega churches to truly impact the structural factors that create poverty”(

Miller and Yamamori 2007, p. 62).

Meanwhile, as the general overseer, Adeboye’s political posturing is ambiguous. For example, as the president of the Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria (1992–1995), he asserted that “God is not a democrat, he does not work with numbers.” This statement has been variously interpreted as “decision-making based on majority opinion did not originate in God” and “democracy is not God’s ideal political system of government” (

Ojewole and Ehioghae 2018, p. 327). Despite his global stature as one of the most influential people and access to Nigeria’s political seat of power, Adeboye identifies with campaigns against the killings in parts of Nigeria. For example, on 2 February 2020, Adeboye led a public protest against insecurity in Nigeria. Tagged, ‘All Souls are Precious to God,’ Adeboye and his team of pastors walked The Redemption Way in Ebute Meta, Lagos Mainland, carrying placards.

Overall, RCCG has combined its spirituality with the secular notion of societal transformation by establishing partnerships involving the renovation of public and government institutions in health care and educational services. This approach is significant in challenging the general notion that Nigerian Pentecostals exploit their members and take advantage of Nigeria’s socio-economic condition to enrich themselves. CSR shows that looking for uniform patterns of development obscures innovative approaches to social vision, which the RCCG exemplifies. It also overlooks the fact that Pentecostal “diverse struggles for social transformation” are shaped by context (

Shaull and Cesar 2000, p. 212). Moreover, in Africa, the individualism often associated with models of Pentecostal piety is corrected by African communitarian values, whereby moral and religious discipline are expected to mediate socio-economic development. However, this spirituality nurtures the human materialistic tendencies that fall within the neoliberal approach to prosperity, thereby leaving many others to struggle with structural poverty.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that social ministry has been part of Pentecostal mission, thereby debunking the myth surrounding Pentecostalism’s lack of social vision. It was noted that this myth was derived from the scarcity of publications rather than anti-intellectualism or theological orientation. Moreover, the myth surrounding the disharmony between the theological and ethical dimensions of Pentecostal social vision is unfounded, based on the fact that context weighs more in their missional agenda than these theoretical formulations.

Based on primary and secondary sources, this paper argues that RCCG, a significant member of African Pentecostalism, has inserted itself into the Nigerian situation to mediate societal and personal transformation. This transformation agenda is founded on altruistic generosity, through which RCCG promotes education, health care, sports, arts, media, culture, and governance. However, CSR, as sponsored by RCCG, is weak in transforming society and as a tool for national development.

However, based on the Weberian framework, this agenda is capable of triggering the upward social mobility of members. This development has been shown to promote prosperity and reduce poverty. This paper also observed that applying the Weberian theory to the African context ignores its historical and intellectual milieu. Finally, we observe that the religion and development discourse has not been fully explored within the fields of theology and religious studies. Therefore, we suggest a fieldwork study on development studies from the perspectives of theology and religious studies.