1. Introduction

Despite biblical prohibitions (e.g., Ex 20:4; Dt 5:8) and scepticism towards human-made images (e.g., Is 44:9–20; Jer 10:5), the visualisation of biblical content has played an important role in religious education for centuries. One notable example is the medieval Biblia Pauperum, which used images, stained glass, and paintings to convey the faith (

Bastock and Jardine 2017). Today, illustrated Bibles for children, youth, and adults—often based on established iconographic canons—serve didactic, catechetical, and spiritual purposes. The significance of visualisation is growing, particularly in light of declining religious socialisation in Western societies (e.g., Germany;

EKD 2024) and the pervasive presence of images on social media (

Gallus and Kriebitzsch 2017). Current socio-cultural trends have led to increasing calls in biblical education for a paradigm shift away from traditional text-centred approaches (for an overview, see

Schambeck 2009, pp. 17–67;

Schambeck 2015, p. 1) towards image-based methods, such as reception-aesthetic Bible teaching (

Fricke 2012) or visual-interactive Bible teaching (

Pirker and Mayrhofer 2020). In an era of rapid technological advancement in generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), these approaches are gaining new relevance and pedagogical potential. Tools such as ChatGPT enable interactive and adaptive engagement with biblical content (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025) and, through the integration of text-to-image technologies (e.g., DALL·E), open new possibilities for creating biblical visualisations accessible to a broad audience. However, like all AI-generated content, these images are not ideologically neutral and may not always align with the principles and values of religious communities (

Makimei et al. 2025). Their use, therefore, requires not only theological expertise but also critical reflection and conscious integration within the framework of biblical education.

Recognising the necessity of the “visual turn” (

Pirker and Mayrhofer 2020, p. 102) in biblical teaching, the authors argue that images should be regarded as equivalent to texts as sources of knowledge and interpretation. Their autonomy as carriers of meaning, as well as their specific visual rationality, should be acknowledged (

Makimei et al. 2025; see also

Pirker and Mayrhofer 2024;

Pirker 2021). Against this backdrop, the article undertakes a critical exploration of contemporary visualisations generated by AI models such as DALL·E in the context of biblical teaching. To achieve this, the analysis is structured into four steps: First, the role of images in biblical education is discussed. Next, the possibilities and limitations of GenAI in creating religious visualisations are examined. The core of the article is a case study involving a critical analysis of AI-generated images of the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan (Mt 3:13–17; cf. Mk 1:9–11; Lk 3:21–22; Jn 1:31,34) and the Last Supper (Mt 26:17–30; cf. Mk 14:12–16; Lk 22:7–13). The aim is to evaluate the potential of these images concerning their biblical and didactic value, taking into account theological, symbolic, aesthetic, and reception-related aspects. The article concludes by summarising the main findings and formulating practical recommendations.

From the outset, it is important to note that this study considers Bible teaching within the context of Catholic religious education in primary and secondary schools, as well as parish catechesis. In a broader pedagogical perspective, the discussion is also applicable to the professional training of religious education teachers and catechists. It may further be relevant to other educational settings where visual materials support the interpretation of religious texts, such as in interreligious and intercultural teaching contexts.

2. Role of Images in Biblical Teaching

Firstly, the term

image, which is often used synonymously with illustration, requires clarification. Following

Keuchen (

2020, p. 1) and the reflections of art historian W. Dörstel, the following functional definition is adopted: “every image in a book, every non-written element with symbolic significance, and every transcultural aspect of a text with symbolic meaning is an illustration” (

Dörstel 1987, p. 118).

This understanding of the concept of the image is closely linked to its didactic application, particularly in biblical teaching. As noted in the introduction, this application has a long and rich history. While a detailed account cannot be provided here, several significant developments are worth highlighting. For example, Pope Gregory I the Great (c. 540–604) emphasised the pedagogical role of images, and in the Middle Ages they were primarily employed as catechetical tools to support the proclamation of the Gospel. Their religious value, however, was considered relative; images served mainly as reminders and illustrations (

Burrichter 2015, pp. 1–2). During the Reformation, particularly in the pedagogy of Jan Amos Comenius (1592–1670), a growing recognition emerged of the capacity of images to convey meanings beyond the literal sense of the text. This marked an important step towards the development of visual education (

Burrichter 2015, p. 2). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, within the context of the Enlightenment, the emotional and aesthetic dimensions of images became more widely acknowledged. This shift influenced the methodology of religious education, particularly with children and young people (

Burrichter 2015, p. 2). In the twenty-first century, developments in image didactics and art education have led to symbolic and hermeneutic approaches to images, broadening their didactic function to include new media such as film, photography, and contemporary art (

Burrichter and Gärtner 2014). Over time, images have evolved from mere catechetical aids to integral components of religious education, engaging the senses, stimulating reflection, and fostering students’ aesthetic and emotional development. Today, they are increasingly recognised as an independent medium with unique educational potential, capable of facilitating a deeper understanding of religious content in a contemporary context (

Burrichter 2015, pp. 4, 9–12; cf. also

Gärtner 2011;

Gärtner and Brenne 2015).

Acknowledging the unique characteristics of images has led to the development of various strategies for their use in religious and biblical education. Particularly in work with children and young people, three main types of images can be identified as playing a fundamental role in the teaching process, according to

Landgraf (

2009, p. 72) and

Adam (

2018, p. 549):

Narrative images: Such images present biblical narratives or particular elements visually, encouraging deeper engagement with the story and enhancing accessibility through visualisation.

Informative images: Drawings or photographs classified as informative images offer essential information about the biblical stories’ historical setting and visual environment. They portray landscapes, buildings, and people, supporting the communication of factual knowledge.

Hermeneutic images: Conveying deeper meanings, these illustrations require careful observation and thoughtful interpretation. They include artistic works and symbolic representations that reflect fundamental human emotions, such as joy and suffering. They reveal hidden dimensions of biblical content, inviting contemplation and theological reflection.

In light of the above considerations, it can be concluded that there is no single, universal “pictorial” approach to visualising biblical content in religious education. More often, the three core functions of images—cognitive, emotional, and motivational—are interwoven. Illustrations fulfil a range of purposes: they instruct (docere), move (movere), and delight (delectare). In this sense, images support the reading and understanding of biblical texts by providing contextual knowledge (docere), while simultaneously encouraging reflection on existential and social questions, as well as on personal life orientation through memorable visual representations (movere). At the same time, they playfully stimulate curiosity and engagement, motivating learners to engage with the Bible (delectare) (

Keuchen 2020, p. 4).

Given their diverse functions, images can be integrated into the teaching process at various stages of learning. In biblical education—both in schools and in parish settings—the use of images may accompany several phases: introduction, attention-focusing, topic initiation, problem formulation, content development, deepening, consolidation, and revision (

Landgraf 2009, p. 74;

Keuchen 2020, p. 5). Various methods from the field of art education can be applied, including image meditation for calming and centring, questioning an image, analysing it through guided questions, comparing multiple depictions of the same biblical scene, working with image-based puzzles (e.g., copying, cutting, folding), and transforming images by repainting or altering them (

Keuchen 2020, pp. 6–7; cf. also

Landgraf 2009;

Burrichter and Gärtner 2014). In addition to these traditional approaches, digital and virtual formats are becoming increasingly relevant, especially within creative Bible teaching projects (

Pirker and Mayrhofer 2020). One example is the creation of biblical “graphic novels” as a form of visual storytelling (

Keuchen 2020, p. 8; cf.

Seesengood 2018). In this context, GenAI could be a valuable tool for encouraging creative and diverse approaches to visualising biblical content. In the next section, we will explore its potential and limitations in the context of biblical education.

3. GenAI and Religious Imagery in Biblical Teaching: Potential and Limitations

GenAI is a specialised subfield of general AI that uses advanced machine learning techniques, large data sets, and algorithms to generate new content. While these algorithms aim to produce unbiased results, their neutrality is increasingly being questioned (

D’Onofrio 2024, p. 332). Key tools in this domain include text-based systems such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek, music generators like Udio and Suno, and image generators like Midjourney and DALL·E. Of particular interest is ChatGPT-4o, an omnimodal model introduced in May 2024, which integrates text-, audio-, and image-processing capabilities within a single system (

OpenAI 2024;

SAS Institute n.d.). Integrating DALL·E into ChatGPT enables users to generate images based on text prompts that are automatically refined by the AI itself (

Cooper and Tang 2024, p. 557). Against the backdrop of the rapid evolution of these technologies, the integration of generative AI into biblical education offers new opportunities for visualising religious texts, as previously noted. It enables innovative approaches to the creation and interpretation of educational content. However, these potentials must be considered alongside significant epistemic, cultural, and theological limitations (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025).

According to

Makimei et al. (

2025), the fundamental potential of GenAI in biblical teaching lies in its ability to visualise content that students often find difficult to imagine. This includes, for example, scenes from the Old and New Testaments, historical and cultural aspects of ancient Middle Eastern societies, and the spatial layout of the temple. AI-generated visualisations can enhance comprehension, foster emotional engagement, and stimulate narrative imagination. Furthermore, GenAI’s personalisation capabilities enable the production of illustrations adapted to the cultural and age-specific context of the target audience. This promotes inculturation and facilitates a deeper understanding of the religious message (

Albia et al. 2023;

Barlow and Holt 2024;

Zhang et al. 2025). Additionally, GenAI imaging tools “democratise” access to visual resources, particularly in educational environments lacking traditional iconographic materials (

Makimei et al. 2025;

Alfano et al. 2024). GenAI can activate learning processes by enabling students to create their own images based on biblical texts. This deepens individual engagement and fosters theological reflection, discourse, and dialogue (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025). AI-generated imagery can also be compared with classical artworks for theological and aesthetic analysis (

Makimei et al. 2025). Indeed, the limitations of GenAI may paradoxically serve as a starting point for meta-theological reflection, revealing its deeper potential. What constitutes an image within a religious framework, and what purpose does it serve? Where lies the boundary between “representation” and “icon”? Can AI systems, which lack volition and spirituality, truly reveal or interpret the sacred?

Despite the educational potential outlined above, the use of GenAI in biblical teaching raises several serious concerns. Academic literature emphasises that images generated by AI often lack essential features of human creativity, such as originality, cultural embeddedness, emotional depth, intentionality, and conceptual coherence (

Makimei et al. 2025, p. 1; see also

You et al. 2015;

Campos et al. 2017;

Chatterjee 2022;

Herzfeld 2024).

Alfano et al. (

2024) point out that the DALL·E system consistently omits explicit religious references, a phenomenon they describe as religious “exnomination” (

Alfano et al. 2024, pp. 2–4). Even when the prompts directly mention biblical figures, the generated images tend to avoid traditional Christian iconography—for example, crosses or halos (

Alfano et al. 2024, pp. 7–9). This results not only in a “neutralisation” of religious imagery but also in its theological “invisibility”. Christianity, with its long-standing tradition of sacred art, appears especially vulnerable to aesthetic censorship in the space of AI-generated visuals (

Alfano et al. 2024, pp. 10–11).

Similar conclusions are reached by

Makimei et al. (

2025), whose analysis of 7000 images generated by DALL·E 2 and Midjourney revealed that DALL·E produces the least accurate results in terms of iconography and narrative coherence. The images often feature distorted figures, an absence of contextual understanding, and random or misleading captions. The system fails to recognise symbolic references (e.g., the twelve apostles); cannot distinguish between literal and allegorical levels of meaning; and frequently generates anachronistic combinations, such as depicting Jesus with a cross at the Last Supper. While models like DALL·E may formally imitate the visual style of religious art, they fall short of accessing its hermeneutical depth or realising its spiritual and contemplative aims (

Makimei et al. 2025, pp. 9, 11–12).

Furthermore, scholars have noted that AI-generated images reflect the cultural assumptions and biases inherent in the training data (

Herzfeld 2024;

Makimei et al. 2025). Religious images produced by these systems often reproduce dominant Western Christian visual codes. For example, Jesus is often portrayed as a white man with European features, an image popularised in the 19th century by artists such as Warner Sallman (

Morgan 1996). Such images may also privilege symbols characteristic of American Protestantism while ignoring the historical and ethnic context of the biblical world. The strong influence of Protestant iconography—particularly from the United States (

Meyer et al. 2010;

Brummitt 2022)—results in the dominance of abstract, symbolic representations. AI models trained on such data sets reproduce this Protestant scepticism towards materially embodied forms of religion, including icons, statues of saints, and ornate religious architecture (

Abrar et al. 2025;

Alfano et al. 2024;

Herzfeld 2024).

In this context,

Chrostowski and Najda (

2025) emphasise the importance of recognising that using GenAI as the only hermeneutical and visual tool in biblical education raises serious ethical concerns. Such systems may implicitly prioritise certain theological traditions or interpretative frameworks over others (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025, p. 4). From a social-theological perspective, it is also important to note that large language models tend to exhibit a bias towards content that aligns with a moderately liberal form of humanism (

Elrod 2024, p. 24). On the one hand, this bias serves a protective function by filtering out extremist or fundamentalist positions. However, it also poses the risk of marginalising minority perspectives or unconventional viewpoints. This concern is particularly pertinent given the growing role of GenAI in shaping worldviews, especially among young people who may uncritically absorb the stereotypes and biases embedded in chatbot-generated content (

Tzeng 2024, p. 5;

Chrostowski and Najda 2025, p. 4). Against this background, it is clear that GenAI should only be used as an additional resource or a provisional dialogue partner in biblical teaching, and never as a substitute for direct human interaction in the classroom (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025, pp. 85–89; cf. also

Chrostowski 2023,

2024a;

Heger 2023).

In conclusion, GenAI has the potential to enhance biblical teaching considerably. However, this can only be realised by taking a reflective approach that considers theological and pedagogical aspects seriously while avoiding the oversimplification and fetishisation of technology. Teachers and students must therefore possess in-depth theological and technical competencies, including foundational knowledge of GenAI, AI literacy, and leadership skills in the responsible use of AI. Only then can the teaching and learning process—including the evaluation, regulation, and co-creation of AI-generated content—be responsibly and constructively shaped within the framework of biblical didactics (

Chrostowski 2025).

4. Case Study: Examining DALL·E’s Imagery for Bible Teaching

After outlining the theoretical background, we present a case study examining DALL·E’s imagery for Bible teaching. The aim is to determine whether AI-generated depictions of biblical scenes adhere to or subvert stereotypical religious iconography. The remainder of the chapter describes the methodology employed (

Section 4.1) and offers a critical analysis, from a Catholic theological standpoint, of four images produced by the DALL·E system (

Section 4.2). The scenes depicted include the Baptism of Jesus (

Section 4.2.1) and the Last Supper (

Section 4.2.2). These scenes were deliberately selected as they portray pivotal moments in the life of Jesus that are deeply rooted in Christian iconographic tradition, symbolising the commencement and conclusion of his public ministry. Analysing these visualisations enables us to examine how the GenAI model reconstructs or deconstructs established visual patterns, while also facilitating reflection on the educational potential of such images. Our focus lies on the aesthetic, symbolic, and theological patterns employed by the AI (also in comparison with selected works of art); the possible impact of such visualisations on students’ religious perception and understanding of biblical texts; and the risk of doctrinal or cultural distortions resulting from the uncritical use of AI in religious education. While previous research has primarily addressed the spiritual, cultural, and ethical dimensions of AI-generated religious imagery (

Makimei et al. 2025;

Herzfeld 2024;

Abrar et al. 2025;

Alfano et al. 2024), the direct application of AI in biblical teaching contexts has largely been overlooked.

4.1. Methodology and Research Questions

The study utilised text-to-image GenAI through the DALL·E 3 system, integrated within the ChatGPT-4o environment. This tool was selected based on its accessibility, the reproducibility of the experiment, and the possibility of linking the generated visual materials with didactic reflection. Three research questions guided the investigation: 1. How does DALL·E, when integrated with ChatGPT, visualise selected biblical scenes, for example, as narrative, informative, or hermeneutic images, or as a hybrid of these forms? 2. To what extent do the generated images reflect Western European cultural patterns and stereotypical religious representations, and in what ways do these manifest? 3. What are the didactic potentials and limitations of using DALL·E-generated images in the context of Bible teaching?

DALL·E was selected for this study for two reasons. Firstly, it is one of the most accessible and user-friendly AI image generation systems, ensuring consistent results within the ChatGPT-4o environment. Its ability to integrate textual and visual inputs makes it particularly well-suited to Bible didactics, where scriptural analysis and image interpretation can be closely connected. Secondly, DALL·E has already been the subject of academic discussion regarding religious imagery (

Makimei et al. 2025;

Alfano et al. 2024), enabling the present study to contextualise its findings within existing scholarship.

To generate the images, a two-tiered prompt strategy was employed. First, non-specific prompts—similar to those used in the study by

Cooper and Tang (

2024)—were applied: Create an image of the biblical scene of Jesus’ baptism in the River Jordan, based on Mt 3:13–17 (a comparable instruction was used for the scene of the Last Supper in Mt 26:17–30). These deliberately vague prompts were intended to reveal how the AI system independently interprets biblical content and which iconographic patterns it reproduces by default. Second, more targeted prompts were used, incorporating explicit references to Catholic symbolism and contextual information regarding the image’s intended didactic use: Create an image of the biblical scene of Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan, based on Mt 3:13–17, including references to Catholic symbolism, intended for use in religious education. This stage aimed to assess the extent to which generative AI can produce visualisations aligned with traditional religious symbolism when provided with precise instructions. It also served to explore the didactic potential of this form of “programmed” visual communication. This two-stage approach enabled a differentiated evaluation of the current capabilities and limitations of GenAI in this context, while also underscoring the importance of critically analysing AI-generated content within biblical education. It should be noted that the images were generated with a single input in June 2025 and that repeating the same commands at a later date would likely produce different results. This is primarily because of the evolving nature of the conversational context and the specific model version that would be used at that time (

Cooper and Tang 2024, p. 558). Finally, to ensure methodological transparency, the first image returned for each case was selected for analysis, and no iterative modifications to the prompts were applied. As the objective was to evaluate the system’s initial output without adjustment, the study did not involve interactive refinement of the images to incorporate Christological symbolism, for example. No additional outputs were stored beyond the selected images. However, future research could explore repeated or refined prompting to assess reproducibility and the potential for integrating additional theological or iconographic elements.

4.2. Critical Evaluation of the Material: Biblical Scenes According to DALL·E

Based on the outlined methodology and the specific research questions, we now proceed to analyse the images generated by DALL·E for the selected biblical scenes. Each example will be evaluated concerning its alignment with traditional iconography, the presence of religious symbolism, and its educational value. As previously noted, the analysis will also consider potential simplifications, distortions, and culturally embedded patterns originating from the model’s training data.

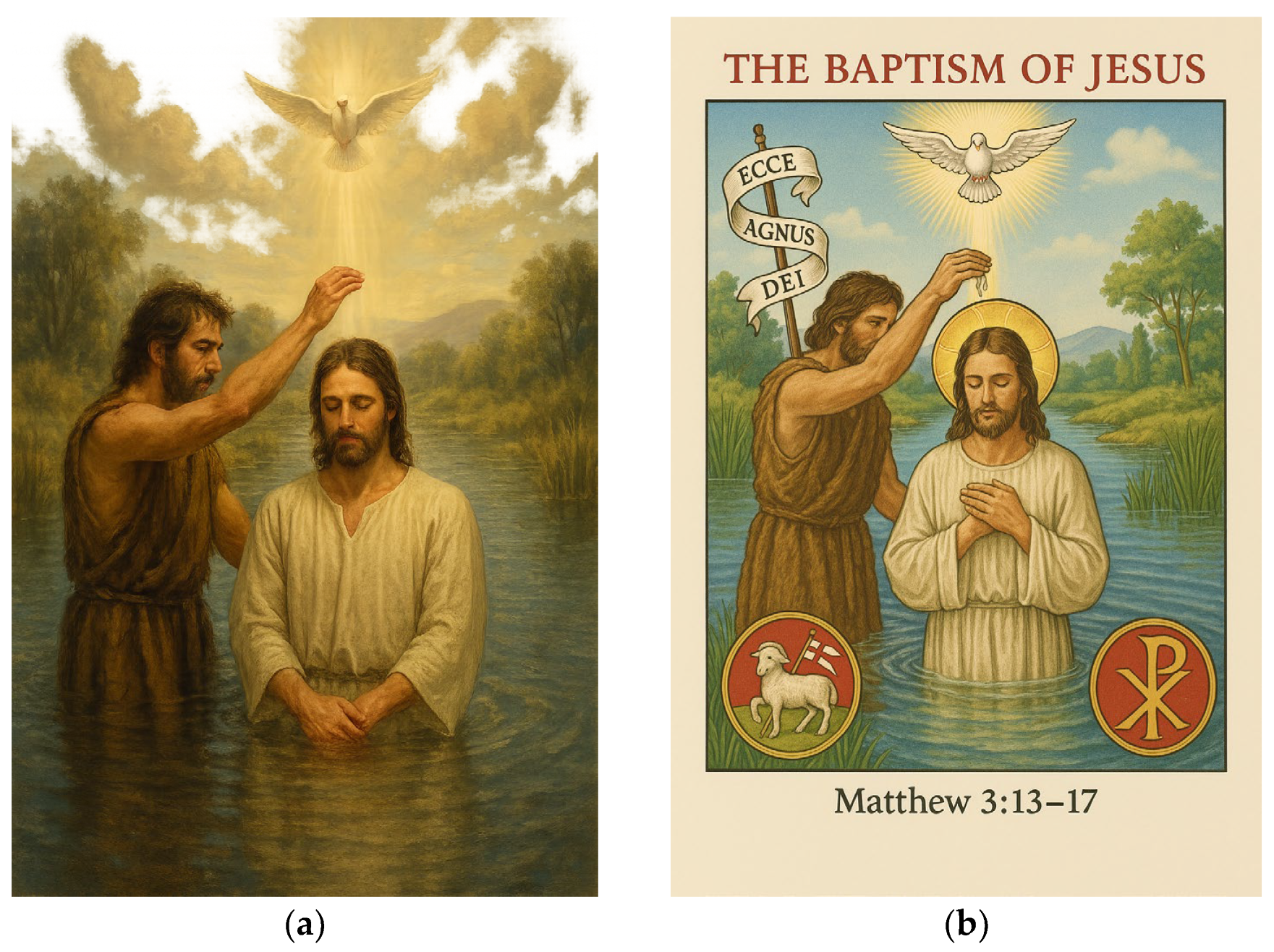

4.2.1. The Baptism of Jesus (Mt 3:13–17)

The passage describing Jesus’ baptism in the River Jordan (Matthew 3:13–17) is one of the most theologically significant texts in the New Testament, intertwining Christological, trinitarian, and sacramental themes (

Nyarko 2024). Within the Catholic tradition, its interpretation is inextricably linked to the concept of epiphany—the revelation of the Son, the Spirit, and the Father (CCC 1223–1225). The scene carries substantial semantic tension and calls for an expanded hermeneutical approach (

Beetschen 2023, p. 8), along with a complex symbolic interpretation involving motifs such as water, light, the dove, and the heavenly voice (

Grethlein 2020, pp. 129–42). In this context, the question of how to visualise this scene in biblical teaching takes on particular importance. Here, images are not merely aesthetic additions; depending on their form, they can either significantly enrich or diminish the understanding of key theological content. Within the ChatGPT-4o environment, we used the DALL·E 3 model to generate two illustrations of this scene.

A critical analysis of these two AI-generated images suggests that, while GenAI can produce a depiction involving Jesus, John, a dove, and water that resembles a narrative structure, it does not reach the threshold of iconic sacredness. According to the tripartite categorisation developed by

Landgraf (

2009) and

Adam (

2018),

Figure 1a is thus best described as a realistic, naturalistic image that primarily serves a narrative function. However, the digital aesthetics typical of GenAI lack iconographic depth, as they fail to comprehend cultural and theological codes. This is evident in the absence of a halo—an iconographic symbol of divinity or holiness (

Sill 2011)—as well as in the lack of Christological symbolism or references to the Father, such as the heavenly voice. This image reflects an aesthetic strategy of “demythologising” the sacred, which may contribute to the neutralisation of the religious dimension of the biblical text (

Makimei et al. 2025). It is also important to note that, according to Mt 3:16, the heavens open and the Spirit of God descends like a dove upon Jesus only after he emerges from the water—an essential theological detail often omitted in such visualisations.

Conversely,

Figure 1b, titled and given a biblical reference by GenAI, appears to be theologically richer at first glance. Featuring the Chi-Rho symbol, the image of a lamb, and the text “Ecce Agnus Dei”, this image aspires to the category of a hermeneutic image (

Landgraf 2009;

Adam 2018). However,

Herzfeld’s (

2024) analysis reveals that GenAI employs symbols as indirectly related graphic “additions” that frequently remain detached from the narrative context. These elements are not integrated into the image’s structure but are instead superimposed onto it, constituting an iconographic collage rather than a sacred composition. The most critical error is the inclusion of the phrase “Ecce Agnus Dei”, spoken by John the Baptist in the Gospel of John (Jn 1:29), but not in the Gospel of Matthew’s description of Jesus’ baptism. These words, said by John the Baptist, testify that Jesus is the Son of God (Jn 1:34). This represents an instance of iconic anachronism, whereby the symbol becomes detached from its theological roots (

Abrar et al. 2025). In this context, DALL·E fails to distinguish between “representation” and “icon”. It does not grasp the concept of epiphany or the trinitarian code. While AI-generated images may resemble religious “representations”, they do not become “religious images” in the theological sense. As

Chrostowski and Najda (

2025, p. 78) emphasise, GenAI cannot read intentions. By replicating “neutral” visual patterns, it can supplant the theological message with an illustrative “appearance”. This is particularly evident when compared to traditional works of sacred art, which are rich in religious symbolism. Examples include Andrea del Verrocchio’s (1435–1488) and Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452–1519) painting “Battesimo di Cristo” (

Parenti 2025).

From a biblical-didactic perspective, the above images require correction and, in many respects, near-complete reconstruction in light of their symbolic inaccuracies (

Kropač 2003). Neither fulfils the informative function as defined by

Landgraf (

2009) and

Adam (

2018), as they fail to convey the historical and cultural context of the depicted events. For example, there are no references to the religious and social realities of Judaism during Jesus’ lifetime. Both images also reflect the “smoothed” aesthetic typical of digital culture. As

Makimei et al. (

2025) and

Alfano et al. (

2024) have observed, this aesthetic is shaped by Western cultural norms—evident in the Europeanised features of Jesus—and by iconographic and symbolic simplifications associated with American Protestantism. Ultimately, these images expose the limitations of technological representations of religion. They can—and indeed should—be used in biblical education, but only within a framework of critical and reflective engagement. For instance, they may serve as a starting point for discussions with students about what remains invisible, what has been omitted, and which theological meanings have been trivialised or neutralised. GenAI should not function as an “image master”, but rather as didactic material for the theological dissection of images. This approach, however, requires a form of religious visual literacy (

Manera 2025, p. 543) and substantial theological knowledge, both of which are increasingly lacking among students due to declining patterns of religious socialisation (

Chrostowski 2024b, p. 76).

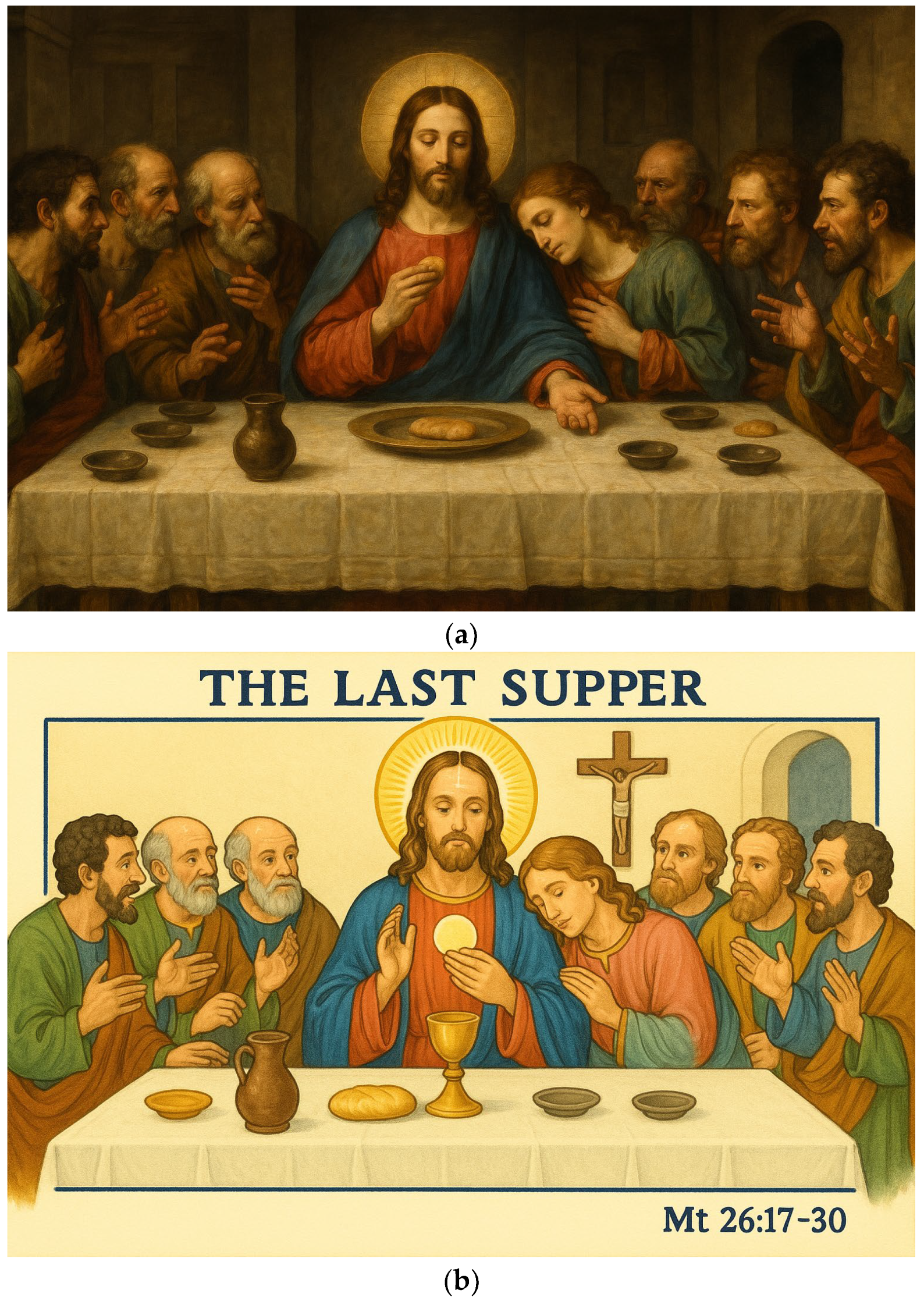

4.2.2. The Last Supper (Mt 26:17–30)

Another visualised biblical passage, Mt 26:17–30, depicts a pivotal moment of faith: the institution of the Eucharist on the eve of Jesus’ Passion. Set within a Jewish cultural, social, and religious context, the scene is highly significant, as it shows Jesus celebrating Passover while imbuing the ritual with new messianic meaning (

Pitre 2015). Jesus not only offers himself as a gift in the form of his body and blood but also reveals betrayal and the isolation of his mission (

Wilson 2023). In the context of biblical teaching in schools, the account of the institution of the Eucharist provides a foundation for interpreting biblical texts within various traditions, including Catholic and Protestant. In parish settings, by contrast, this practice takes on a more participatory and experiential dimension (

Reis and Grethlein 2018, pp. 6–7). Furthermore, this pericope offers a valuable opportunity to demonstrate the creative transformation of Jewish tradition by Jesus himself within Christian interpretive frameworks (

Gleeson 2021;

Bradshaw 2023). During educational processes in both schools and parishes, images that support an understanding of the text’s multi-layered meanings can play a vital role in helping students engage with the narrative, encouraging interpretation and stimulating theological imagination (

Keuchen 2020, p. 4). To illustrate this pericope, we generated two images using the DALL·E 3 model embedded in the ChatGPT-4o environment.

Figure 2a, generated by AI, attempts to imitate Renaissance depictions. Jesus is positioned at the centre, with the disciples on either side, holding a loaf of bread and a chalice. This composition immediately evokes Leonardo da Vinci’s famous work “The Last Supper” (1452–1519), which offers a far more theological interpretation of the moment of betrayal—where gestures, divisions, lines of gaze, and the disciples’ body language all contribute meaningfully to the scene (

Zelazko 2025). By contrast, the AI-generated image adopts a more classical, “soft” aesthetic reminiscent of nineteenth-century Renaissance-inspired works by artists such as Ary Scheffer (1795–1858) and Carl Bloch (1834–1890).

Figure 2a thus fulfils a narrative function (

Landgraf 2009;

Adam 2018) by portraying the institution of the Eucharist recognisably, even though fewer than twelve apostles are shown. However, it does not provoke deeper interpretation and merely invites the superficial recognition: “This is the Last Supper.” Moreover, the critique offered by

Makimei et al. (

2025) becomes evident here: GenAI reconstructs biblical scenes in a tensionless manner, despite the dramatic structure of the pericope in Mt 26:21–25. Crucially, GenAI operates on the principle of synthetic imitation. It replicates visual forms without understanding their theological significance, to achieve narrative clarity (

Manera 2025).

Against this background,

Figure 2b resembles a stylised educational illustration and repeats the same mistakes. It depicts a European Jesus wearing a halo and holding a host and a golden chalice. A cross appears in the background, and the words “The Last Supper” are inscribed alongside the boundaries of a biblical quotation. The disciples’ outstretched hands resemble the gesture used during the celebration of the Eucharist. Although the image contains religious symbols typically associated with the hermeneutic category, it focuses on the ritual rather than the event itself (

Landgraf 2009;

Adam 2018). The placement of the cross as a decorative element above Jesus—a secondary symbol in Matthew’s narrative—is historically and culturally inappropriate. The Latin-style host and chalice are also elements of post-evangelical liturgy. Furthermore, there is no reference to Jewish Passover symbolism, although the Last Supper takes place on the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Mt 26:17).

Figure 2b is, ultimately, a symbolic “representation” in which GenAI reduces complex theological content to a combination of elements from different contexts—resulting in an aesthetically pleasing yet theologically anachronistic amalgamation (

Alfano et al. 2024;

Makimei et al. 2025).

5. Conclusions

When analysed in the context of the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan (Mt 3:13–17; cf. Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22; John 1:31, 34) and the Last Supper (Mt 26:17–30; cf. Mark 14:12–16; Luke 22:7–13), the images generated by DALL·E primarily expose the structural limitations of AI in representing theological content. In both cases, these illustrations cannot be regarded as autonomous depictions of biblical or doctrinal substance. Rather than offering faithful visualisations of Scripture, they invite reflection on what remains absent or misrepresented. AI-generated images call not for classical interpretation, but for critical unmasking. Instead of illustrating biblical scenes, they challenge students to uncover meaning independently and encourage educators to engage them in a purposeful and reflective learning process. From this analysis, three core conclusions emerge, accompanied by recommendations for the use of such images in Bible teaching:

While our case study’s AI-generated images can depict figures such as Jesus and his disciples, or include religious symbols, they cannot convey theological, emotional, or sacred depth. Despite their aesthetic appeal, these images often remain spiritually superficial and may lead to the simplification or reduction of religious meaning (

Makimei et al. 2025;

Herzfeld 2024;

Alfano et al. 2024). For this reason, AI-generated visuals should be used solely as supplementary materials in biblical education—for example, as starting points for deeper reflection, theological discussion, and dialogical engagement—rather than as definitive representations of theological content. In this respect, theological hermeneutics—including approaches developed within the framework of the “visual turn” (

Pirker and Mayrhofer 2020, p. 102) in biblical teaching—remain essential and irreplaceable (

Chrostowski and Najda 2025).

In our case study, GenAI introduces religious elements as non-integrated additions—for instance, a cross in the background of the Last Supper or the inscription “Ecce Agnus Dei” in the baptism scene—without considering the narrative, historical, or cultural context of the biblical passage. In this sense, the resulting images display a form of iconographic and intertextual hybridisation that primarily serves aesthetic purposes. AI-generated images should therefore be understood as starting points for developing students’ religious visual literacy (

Manera 2025, p. 543), with particular attention to the phenomenon of symbolic dispersion. Religion teachers can guide students in identifying inconsistencies, correcting them, and situating elements accurately within the biblical context. Such tasks can be effective tools for visual debugging in biblical teaching (

Michaeli and Romeike 2019), enabling the critical analysis and revision of AI-generated imagery that is inadequate in theological, historical, or symbolic terms. This approach encourages students to take an active role, transforming them from passive observers into active interpreters. It also fosters critical thinking about the application of GenAI in biblical interpretation and religious education processes (

Chrostowski 2024a).

The primary advantage of GenAI lies in its ability to rapidly produce a wide range of illustrations for specific biblical passages. Such outputs can be particularly beneficial in educational settings where traditional visual representations—especially historical works of art—may be difficult for students to interpret or relate to (

Makimei et al. 2025). Moreover, AI-generated graphics can be adapted to suit the age, aesthetic preferences, or cultural background of a given group. However, this potential for inculturation is only realised when prompts are crafted deliberately and reflectively (

Albia et al. 2023;

Makimei et al. 2025). Despite their simplified character, AI images can foster students’ narrative competence in reconstructing biblical scenes. For example, students might be asked to describe what is happening in the image, consider what each figure might be communicating, or propose additions or modifications to it. Comparing such illustrations with classical artworks—e.g., by Verrocchio or da Vinci—can also help students better understand the theological depth and symbolic richness of sacred art. This method not only activates biblical knowledge but also nurtures the

sensus theologicus: the ability to discern between what is merely aesthetically pleasing and what is theologically meaningful. In addition, students may create their own AI-generated illustrations of biblical pericopes, compare and critique them, and iteratively improve them. In doing so, they develop digital, biblical, and aesthetic competencies in an integrative way (

Chrostowski 2025;

Burrichter 2015;

Gärtner 2011;

Gärtner and Brenne 2015).

Ultimately, it is essential to acknowledge that, despite their apparent neutrality, AI-generated images carry implicit aesthetic and cultural codes that may conflict with Christian tradition and risk perpetuating stereotypes or prejudices. Their educational value, therefore, does not lie in their perceived “perfection”, but in their limitations, which offer a meaningful opportunity for fostering understanding, interpretation, and deeper engagement with religious content. Rather than merely depicting biblical scenes, such images should serve as catalysts for critical reflection and dialogue concerning the theological substance of Scripture and the relevance of its message for individuals and communities alike.

At the same time, the scope of our case study is necessarily limited. It should also be noted that the adequacy of GenAI was assessed here mainly based on relatively simple prompts. While sufficient to reveal key theological and pedagogical limitations, this approach does not account for the potential of more advanced prompt design to produce richer and more contextually accurate results, which merits further investigation. Further research is required to examine a broader range of biblical scenes, religious traditions, and educational settings. In particular, comparative research in an interfaith and intercultural context could shed light on the potential and limitations of GenAI in biblical teaching. This would provide valuable insights into creating a differentiated framework for the reflective and responsible use of AI-generated images in schools and religious communities.