The Publication and Dissemination of the Yuan Dynasty Pilu Canon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Engraving Origin of the Yuan Pilu Canon

(元代)私版《一切經》,上述管主八刻藏。《大普寧寺藏》外,僅有白蓮教刊行四小藏。延祐二年,福建道建寧路建陽縣後山報恩萬壽堂嗣教陳覺琳,募緣雕鐫四大部小藏:《大般若經》六百卷;《大寶積經》百二十卷;《大般若涅槃經》四十卷,同後分二卷;《大華嚴經》八十卷,原八十四函,出資皆庶民階級也。經各面六行十七字,字體秀麗,優於元普寧寺版。“The private edition of the Canon (Yuan Dynasty) was engraved and stored by Guan Zhuba 管主八, as mentioned above. In addition to the Da Puning Temple Canon 《大普寧寺藏經》, there were only four minor canons published by the White Lotus Society 白蓮教. In the second year of the Yanyou reign 延祐年間, Chen Juelin 陳覺琳 from Bao’en Wanshou Hall in Houshan Village 後山報恩萬壽堂, Jianyang County 建陽縣, Jianning Lu 建寧路, Fujian Circuit 福建道raised funds through solicitation and engraved four minor canons: 600 volumes of The Great maha-prajanparamita sutra; 120 volumes of Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra; 40 volumes of The Great Nirvana Sutra; 2 volumes of The Great Prajna Nirvana houfen; and 80 volumes of The Great hua-yan sutra all stored in 84 book wrappers. All the investors were from the commoner class. Each line 行 contained seventeen characters 字, and six lines were arranged on each side of the scriptures. The fonts were elegant and superior to the edition in the Puning Temple.”5

3. The Publishing and Engraving of the Yuan Pilu Canon

3.1. Engraving Timeline and Geographic Scope

3.2. Typefaces and Characters Used in Engraving

| Feature/ Edition | Pilu Canon (Figure 1) | Puning Canon (Figure 2) | Yuanguan Canon (Figure 3) | Yuan-Supplemented Qisha Canon (Figure 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Format | Single-line border on all sides; 36 lines per folio (每折6頁); 17 characters per line | Early phase imitates Song formats; later phase: 30 lines per folio, 17 characters per line; single/double borders; smaller folio size | 42 lines per folio 每折7個半頁; 17 characters per line; double-line borders on upper and lower margins | 30 lines per folio, 17 characters per line; follows Southern Song prototypes; single/double borders; folio size akin to Puning Canon |

| Binding | Accordion binding 經折裝 | Accordion binding; 5.5 pages per folio; includes protective covers and decorative wrappers | Accordion binding; 7 folded pages per folio; frontispiece illustrations of stupas and Śākyamuni preaching | Primarily accordion binding; Yuan-supplemented scrolls feature Yuan-era characteristics, e.g., hemp-paper linings |

| Calligraphic style | Hybrid of Ouyang Xun’s solemnity (Ou style) and Zhao Mengfu’s solemnity (Zhao style); fluid, vigorous engraving techniques, resembling Song engraving | Early phase: Ou style; mid-late phase: Zhao style (slender and elongated); alternates regular and semi-cursive scripts | Influenced by Zhao style, standardized with occasional semi-cursive flourishes | Southern Song origin: Ou-style Zhejiang script; Yuan phase absorbs Zhao style; Yuan supplements incorporate Yan Zhenqing and Zhao styles |

| Layout and orthography | 17 characters per line; occasional colophons 刊版題記 and donor notes 施資題記; predominantly employs vernacular characters | 17 characters per line; carver’s names annotated; uses Thousand-Character Classic numbering system 千字文函號 for folio/section labels; vernacular characters | 17 characters per line; carvers’ signatures (e.g., “Yang Ding carved” 楊鼎刊); standardized orthography | Strict 17-character alignment; Yuan-supplemented colophons note dates and carvers (e.g., “Supplemented in the 10th Year of Dade” 大德十年補刊); standardized orthography |

| Additional features | Survives only in four major divisions; shares origins with Wuxing Miaoyan Temple Canon; emphasizes functionality and cost-efficiency for wider dissemination | Divided into early/late phases; late phase simplifies formats; early-phase fragments survive in Japan; book wrappers feature inscriptions in the style reminiscent of Six Dynasties stele inscriptions | Extant in 23 titles (32 scrolls); postdates Yuan Pilu Canon (exact dates debated); frontispiece-art integration reflects imperial authority | Initiated in Southern Song, completed via Yuan supplementation (c. 1290–1320 CE); Yuan supplements constitute over 75% of the canon; engravers overlap with Puning and Pilu Canons |

3.3. Founding of the Work

4. The Socioreligious Context of the Yuan Pilu Canon

4.1. Religious Names of the White Lotus Society Followers

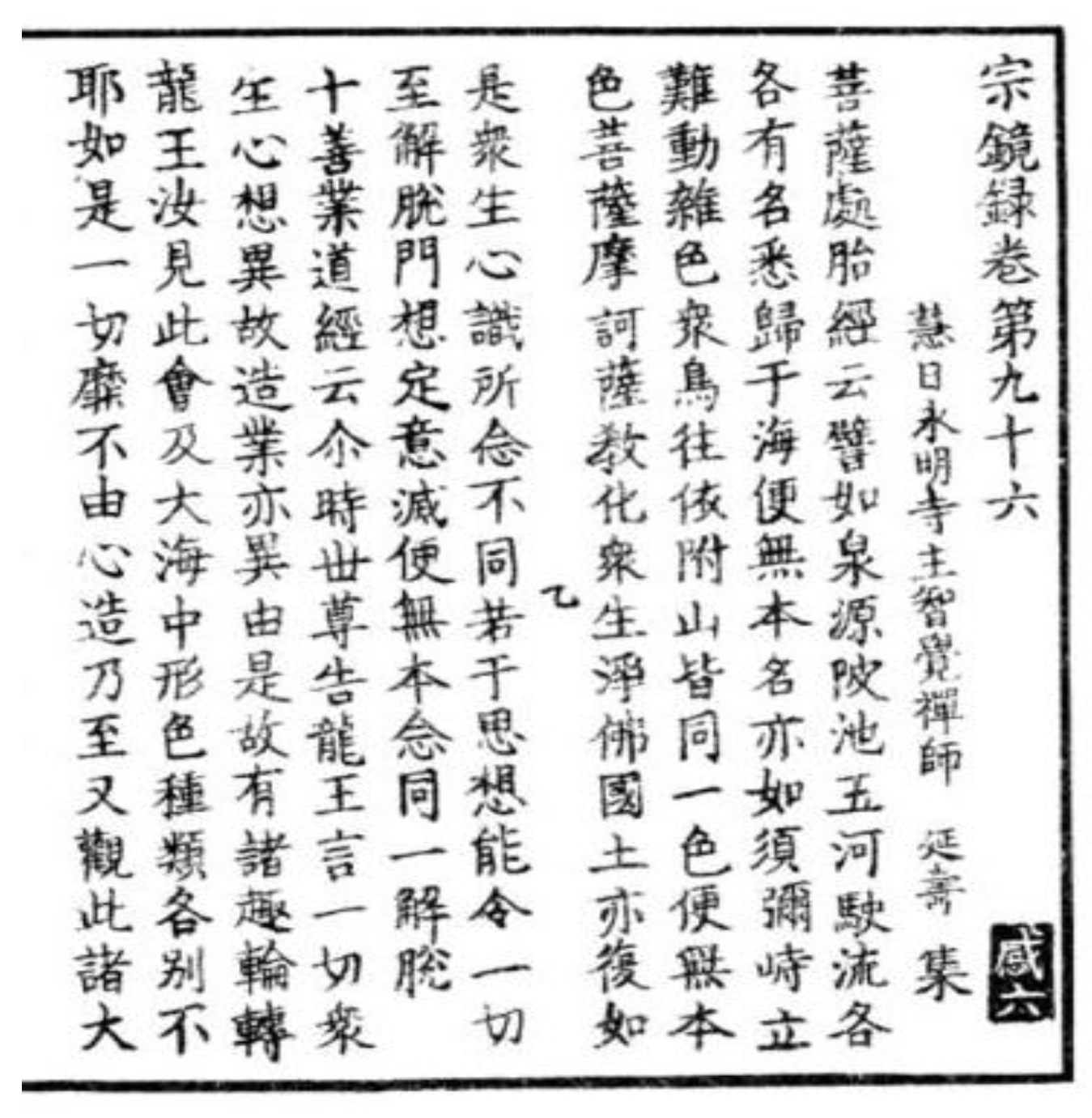

From this, it is clear that within the White Lotus Society, followers used the characters Pu “普”, Jue “覺”, Miao “妙”, and Dao “道” as identifiers for different sects within the broader movement. This suggests that internal divisions had already taken shape, with various factions competing for influence.去聖時遙,人多謬解,雖期正道,悉陷邪宗,庸昏之徒,含識而已,致使群邪詭惑,諸黨並熾,是非蜂起,空有云云,夾截虛空,互相排毀。……有執我宗“普”字“覺”字者,有言彼宗“妙”字“道”字者,是皆私偷此鏡入彼邪域,致爲塵垢蔽蒙,不明宗體,雖得此鏡之名而不得其用也。“The age of the sages has long passed, and many have fallen into misunderstanding. Though they yearn for the right path, they have instead veered into heretical sects. The mediocre and confused are but mere sentient beings. Consequently, countless heresies spread lies to deceive, and sects of all kinds flourish simultaneously. Disputes over right and wrong erupt like swarms of bees, and empty words are endless. These debates seem to cut through the void, as each faction slanders and attacks the others. There are those who cling to the characters Pu “普” and Jue “覺” of our sect, while others promote the characters Miao “妙” and Dao “道” of other sects. All these people secretly appropriate this mirror and bring it into the heretical realms of others, where it is covered in dust and dirt, obscured from the true essence of the sect. Though they claim to possess the name of this mirror, they are unable to use it” (ibid, p. 66).

4.2. Relationships of Solicitors

常熟州承化里何舍土地渡江大王界居弟子嚴憲,同室張氏妙真施財刊第三卷。近景福遠植勝因,歸命總持不動尊,隨眾生而心周徧法界。今我早登乘上覺,度恒沙眾而名報佛恩。“The local deity of the He family in Chenghua Li Village 承化里, Changshu Prefecture 常熟州, crossed the Yangtze River and came to the deity’s shrine. There, my disciple Yan Xian 嚴憲 and his wife Zhang Miaozhen 張妙真 generously funded the engraving and printing of the third volume of the scriptures. Their aim was to accumulate merit in this life and plant the seeds of good fortune for future lives. They dedicated their contribution to the compassionate Acalanatha Bodhisattva, whose mercy extends to all sentient beings and the Dharma realm. I hope that through this merit, I could swiftly attain the highest enlightenment, save countless sentient beings, and repay the Buddha’s kindness”.12

4.3. The Grassroots and Sectarian Nature of the Yuan Pilu Canon

5. Dissemination of the Yuan Pilu Canon

5.1. The Scriptures Bestowed to One Hundred Monasteries: The Edition from the Song Dynasty

5.2. The Four Major Buddhist Canons as the Core

此《大般若經》六百卷,《大寶積經》百二十卷,《大涅槃經》四十卷,皆延祐間福建省嗣教陳覺琳刻,相沿庋置法堂中。我鼓山湧泉寺明清以來,四賜龍藏,而此本久無人披讀,莫知其全缺也。今年夏,門人觀本明一始出而檢之,三經共殘缺四十餘卷。知客清福師倡募裝潢,而首座慈舟法師、西堂寶山師,暨宗壽、興證、通化、聖修、純果、法真、龍洸、慎足、傳道、澄朗、優定、能復諸師等,復發心手鈔,足其卷數。此三部古本大經,乃煥然復新。民國二十一年(1932)壬申歲季秋湧泉寺住持虛雲敬識

The 600 volumes of the Great maha-prajanparamita sutra, 120 volumes of The Great Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra, and 40 volumes of the Great Nirvana sutra were all engraved by the follower Chen Juelin from Fujian Province during the Yanyou reign. These scriptures were stored in the Fa Hall at Yongquan Temple for generations. Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Yongquan Temple on Mount Gu in Fujian has been the recipient of the Long Canon 龙藏 on four occasions. However, these copies had long remained unread, and it was uncertain whether they were complete. This summer, my disciple Kanamoto Myōgi 觀本明一 took the initiative to examine these scriptures. It was discovered that the three texts were missing over forty volumes in total. In response, the Guest Master Qingfu 清福 raised funds for their binding and restoration. The Chief Seat Master Cizhou, the Western Hall Master Baoshan, and Masters Zongshou, Xingzheng, Tonghua, Shengxiu, Chunguo, Fazhen, Longguang, Shenzu, Chuandao, Chenglang, Youding, Nengfu, among others, were also inspired to hand-copy the missing volumes. As a result, these ancient and precious scriptures were fully restored to their original state, appearing as new.Respectfully inscribed by Xu Yun虛雲, the abbot of Yongquan temple 湧泉寺,in the 21st year of the Republic of China (1932)民國二十一年,late autumn of the Ren Shen year壬申歲季秋

5.3. The Yanyou Canon as a Separate Text

5.4. Dissemination and Fragmentation of the Yuan Pilu Canon: Impact of Historical Turmoil

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Yuan Pilu Canon 元《毗盧藏》 is referred to as the re-engraved Pilu Canon. For detailed discussion, see He Mei’s 何梅 Research on Several Issues Concerning the Pilu Canon 《<毗盧大藏經>若干問題考》 (Studies in World Religions 《世界宗教研究》, Issue 3, 1999) and Research on Chinese Canon 《漢文佛教大藏經研究》 (China Religious Culture Publisher, 2003). |

| 2 | Barend ter Haar 田海 argued that the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty was a re-engraved edition 覆刻本 of the Qisha Canon 《磧砂藏》. However, Barend ter Haar cited the Taiwan version 臺灣版 of the Zhonghua Buddhist Canon 《中華大藏經》 (first series), which included a photocopy of the Song Dynasty Qisha Canon published in Shanghai between 1931 and 1936. During the compilation of this photocopy, it was discovered that parts of the Qisha Canon were missing. Due to limited resources at the time, various versions of the Qisha Canon from the Song 宋, Yuan 元, and Ming 明 Dynasties were used to supplement the missing sections, resulting in a version resembling a patchwork edition. Since Barend ter Haar did not have access to the original Qisha Canon or its photocopied version 影印本, he referenced the re-photocopied edition, which no longer preserved the original appearance of the Song Dynasty Qisha Canon (Haar 2017). |

| 3 | Ogawa Kan’ichi, 小川貫弌, was the first to propose identifying the fundraising groups behind the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty. He argued that the White Lotus Sect 白蓮宗 referred only to certain White Lotus societies 白蓮教 led by well-known monks 無名僧 and adhering to strict religious doctrines, such as those at Donglin Templ 東林寺 on Mount Lushan 廬山. In contrast, White Lotus societies widespread among the common people with less rigorous religious doctrines and lacking the guidance of prominent monks could be classified as the White Lotus Society, but not the White Lotus Sect. Ogawa Kan’ichi believed that the hall associated with the Pilu Canon belonged to a mass religious group with shallow doctrines and no guidance from prominent monks, thus falling under the White Lotus Society. Please refer to Ogawa (1943). |

| 4 | In 2008, two volumes of scattered copies of the The Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra from the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty, housed in the National Library of China, along with one volume of the Da Fang guang fo hua yan sutra 《大方廣佛華嚴經》 from the same canon, held in the Shanxi Library 山西省圖書館, were included in the first National Rare Ancient Book Directory 《第一批國家珍貴古籍名錄》. In 2009, one volume each of the The Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra, The Great Nirvana Sutra, and 27 volumes of the The Great maha-prajanparamita sutra from the Pilu Canon, collected in the Nanjing Library, as well as one volume of the The Great maha-prajanparamita sutra from the Pilu Canon, held in the Hubei Provincial Library, were added to the second list 《第二批國家珍貴古籍名錄》. Currently, the Nanjing Library holds the largest collection. |

| 5 | The Buddhist Canon at Puning Temple 大普寧寺 refers to the Puning Canon 《普寧藏》 engraved by Bai Yunzong白雲宗. No complete sets of this canon exist in China, and it is currently primarily housed at Zojo-ji Temple 增上寺 in Japan. |

| 6 | In Zen Buddhism, the Hua-yan sutra 《大華嚴經》, Nirvana sutra 《大涅槃經》, Mahāratnakūṭa sutra 《大寶積經》, and maha-prajanparamita sutra 《大般若經》 are referred to as the four major Buddhist Canons. The “Fangshan department part” 房山部 in New Visits to Monuments in the Capital includes 《新日下訪碑錄》 records of the continued engraving of these four major canons on the East Peak of Yunju Temple on Baidai Mountain in Zhuozhou. 《涿州白帶山雲居寺東峰續鐫成四大部經記》 The four canons mentioned in this context are the same as those referred to above. This shows that the term “four major Buddhist Canons” 四大部經 was consistently applied. |

| 7 | Jianchang Prefecture 建昌州 was originally part of Haihun County 海昏縣 during the Han Dynasty 漢代. In the Liu-Song Dynasty 劉宋, Haihun was divided and incorporated into Jianchang. During the Yuan Dynasty, it was renamed Jianchang Prefecture and came under the jurisdiction of Jiangxi Province 江西省. Luan Prefecture 陸安州, which was part of Luzhou Road 廬州路 in Henan Province 河南省 during the Yuan Dynasty, had its administrative offices in Hefei 合肥. |

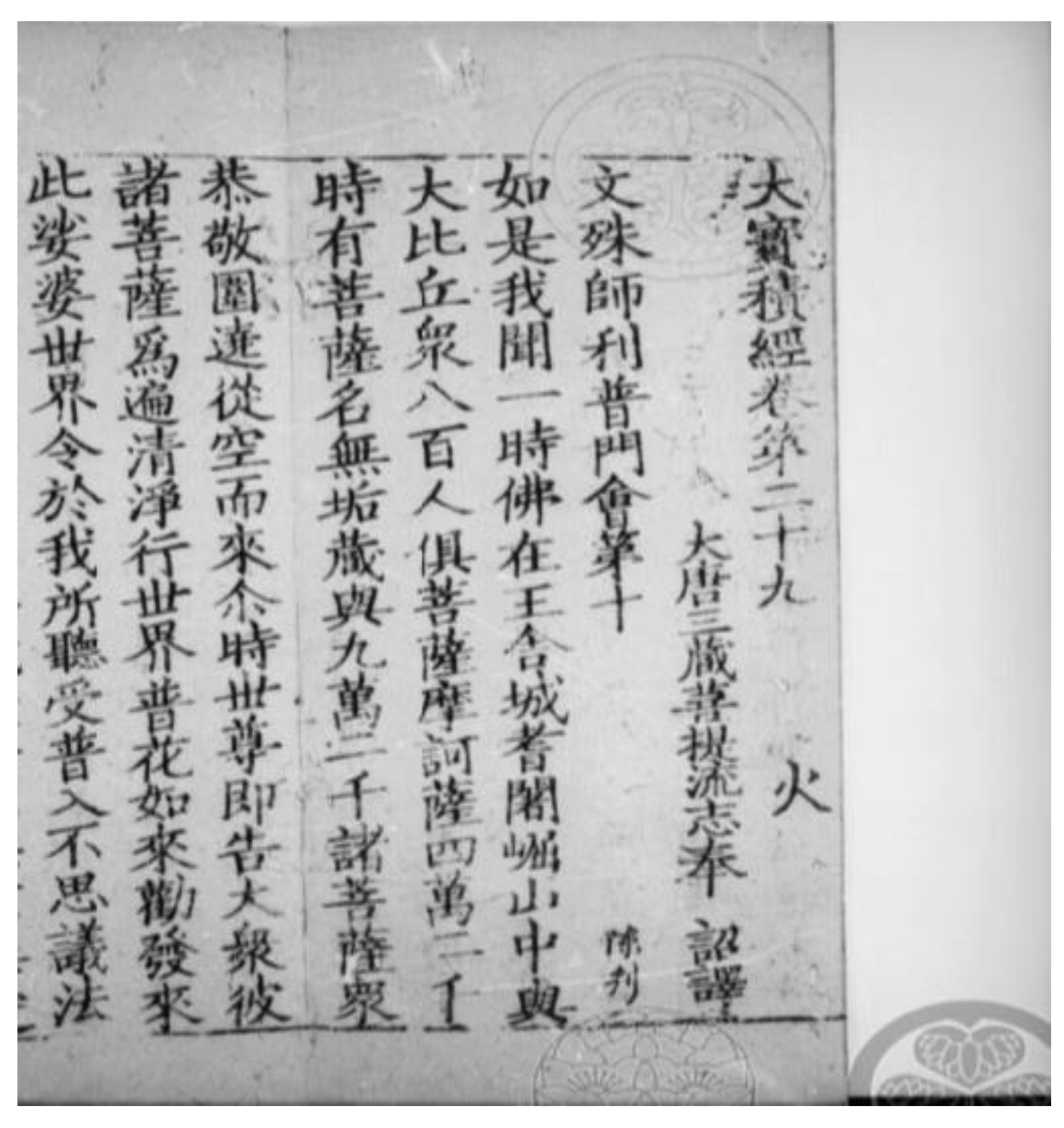

| 8 | This Scattered Version is cited from the “First Batch of National Precious Ancient Books List” and is currently stored in the Shanxi Provincial Library. This image is quoted from the National Rare Ancient Books List database 《國家珍貴古籍名錄資料庫》. Available online: http://gjml.nlc.cn/#/exploration (accessed on 25 November 2024). |

| 9 | This Scattered Version is cited from the website of Zōjōji Temple in Japan and is currently stored in the Zōjōji Temple in Japan. Available online: https://jodoshuzensho.jp/zojoji/yuan/viewer/038/075/09/mir_038_075_09.html (accessed on 13 November 2024). |

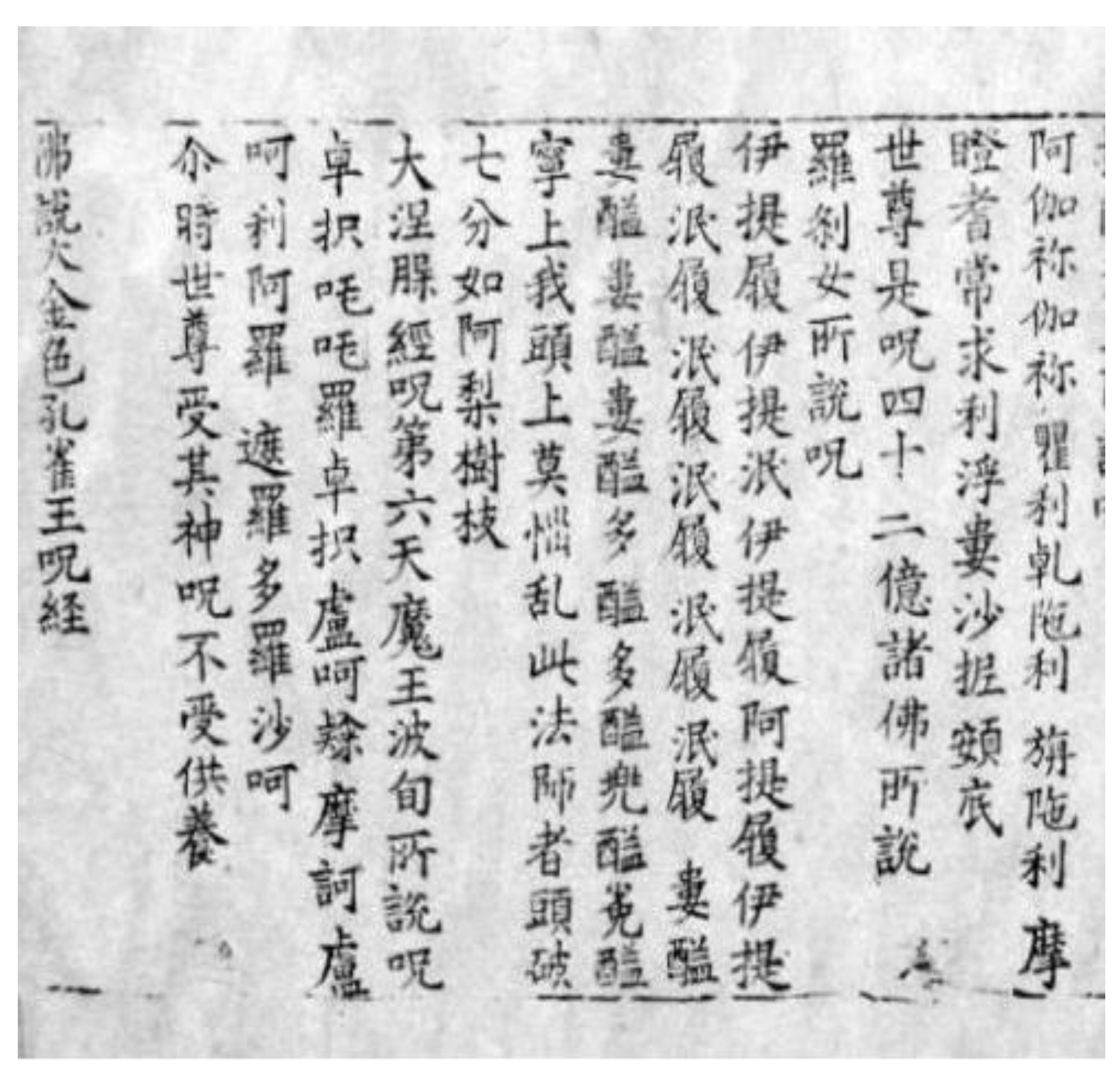

| 10 | This Scattered Version 散藏零本 is cited from the The Yunnan Ancient Books Digital Library 雲南古籍數字圖書館. Available online: http://221.213.44.205/frontend/viewer.html?typeId=80&bookId=278#/page=3&viewer=picture (accessed on 17 October 2024). |

| 11 | This Scattered Version is cited from the Qisha Canon Engraved during the Song and Yuan Dynasties by Photocopy Edition, 《影印宋元版磧砂大藏經》, published by the Thread-Bound Book Press 線裝書局 in 2005, Volume 116. |

| 12 | The engraving records are cited from Volume 3 the of The Interpretation of Big buddha peak Surangama Sutra 《大佛頂首楞嚴經》 stored in the Taiwan National Central Library 臺灣“國家圖書館”. Available online: https://rbook.ncl.edu.tw/NCLSearch/Search/SearchDetail?item=87b031c02ef3444faa3f786e8bc0c33afDc0OTA00.rH0eIummlsBsfF_rfGyzVCqzp91Amg5PIply32ZhzmQ_&image=1&page=&whereString=&sourceWhereString=&SourceID= (accessed on 25 November 2024). |

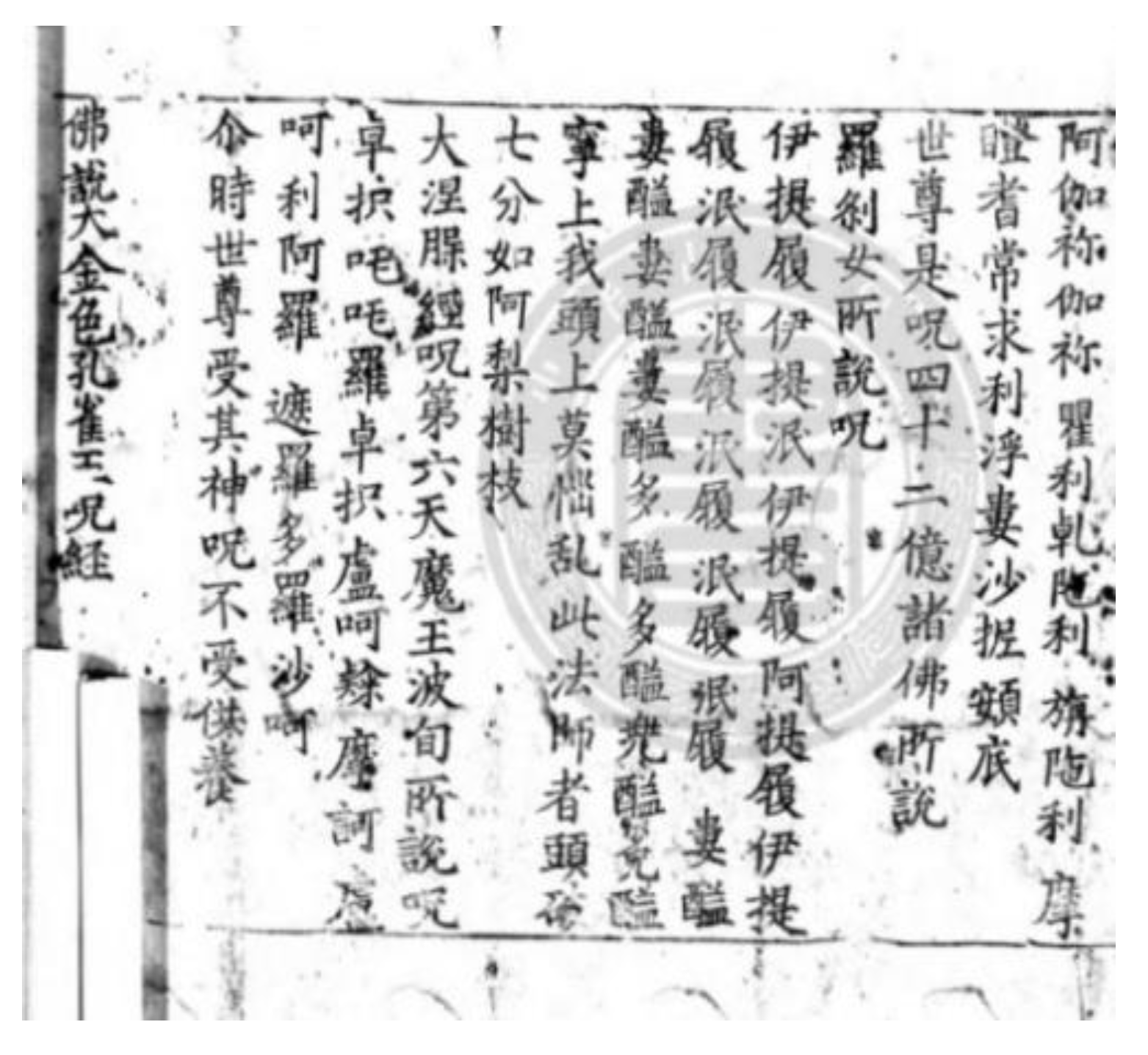

| 13 | This figure was cited from the National Library of China 中國國家圖書館. Available online: http://read.nlc.cn/OutOpenBook/OpenObjectBook?aid=892&bid=199344.0 (accessed on 17 October 2024). This figure also appears in He Mei’s Foshuo Dajinsekongquewang Zhoujing 《佛說大金色孔雀王咒》 of the Yanyou Canon in Zhihua Temple 北京智化寺. |

| 14 | This image is cited from Venerable Juezhen’s 觉真法师 article, A Brief Account of the Unidentified Yuanguan Canon Preserved at Beijing Zhihua Temple 《北京智化寺<不知名元官藏>簡述》, published in Fayin 《法音》, 2003, No. 7, pp. 31–33. |

| 15 | It is evident that the binding format of this Yanyou Canon employs scroll binding 卷軸裝, distinct from the accordion binding 經折裝 characteristic of the Pilu Canon. The example cited by Venerable Juezhen in their article and the case discussed by He Mei pertain to the same sutra scroll: the scroll-bound (juanzhouzhuang 卷轴装) Fo Shuo Da Jinse Kongque Wang Zhou 《佛說大金色孔雀王咒經》. Both examples exhibit identical layout, calligraphic style, glyph forms, and binding format. Consequently, it can be conclusively determined that the so-called “Unidentified Yuanguan Canon” 不知名元官藏 referenced here corresponds to the Yanyou Canon under discussion, rather than the Yuanguan Canon preserved at Yunnan Provincial Library. |

| 16 | Yu, Dafu, 郁達夫 mentioned in the Min you di li 《閩遊滴瀝》 (Travel Sketches of Fujian): “Regarding this scripture, two years ago, a Japanese scholar specializing in Buddhist scriptures came to stay at our temple to make photocopies… And now he is sorting them out in Tokyo. If this photocopied version is sorted out and published, it will cause an earth-shattering stir in the history of Buddhist studies”. It can be inferred that the Yanyou Canon was in the Yongquan Temple 湧泉寺 on Gu Mount 鼓山 in 1936, and Yu Dafu had seen this canon. However, judging by the engraving era and scale, the Yanyou Canon is the Pilu Canon engraved by the Bao’en wan shou Hall in Houshan Village 後山報恩萬壽堂, as detailed in (Pan and Chen 1995). |

| 17 | The version of the “Ming Southern Canon” 明代南藏 mentioned by the author can be further clarified. The Yongle Southern Canon 《永樂南藏》 was historically housed at the Yongquan Temple on Mount Gu in Fujian Province. In contrast, the Hongwu Southern Canon 《洪武南藏》 was only discovered in 1934 at the Shanggu Temple 上古寺 in Chongqing County 崇慶縣, Sichuan Province. At the time of its discovery, this collection already showed minor incompleteness, containing supplementary manuscript copies and commercial printings from later periods. Fang Guangchang 方廣錩, then Director of the Rare Books Department at the National Library of China (Beijing Library), identified it as the sole surviving complete copy in existence 海內僅存孤本. Given these historical and geographical contexts, the “Ming Southern Canon” referenced here unquestionably corresponds to the Yongle Southern Canon. The term “Bound-Printed Canon” “書本藏” here refers to a codex-style 方冊裝幀 Buddhist Canon with book-like binding 形同書本. In his seminal study on the Printing and Circulation of Buddhist Scriptures in Fujian 《談福建的印經與經書流通》, Zhou Shurong 周書榮 systematically documents the extant volumes of Chinese Canon preserved in Fujian Province 福建省現存歷代漢文大藏經卷帙. His research particularly highlights the Jiaxing Canon 《嘉興藏》, also known as the Jingshan Canon 《徑山藏》, an early modern movable-type printing project initiated in the late Ming Dynasty. Zhou’s archival investigation reveals two critical findings: The Yongquan Temple on Mount Gu in Fuzhou preserves partial volumes of this canon, though with significant lacunae. The Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou houses fragmented sections, including the complete tripartite scrolls of Buddha Ascends to the Trāyastriṃśa Heaven to Preach Dharma to His Mother Sūtra 《佛升忉利天爲母說法經》 and Precious Cloud Sūtra 《寶雲經》. |

References

Primary Sources

Edited by Jing Hui, 淨慧. Xu yun he shang quan ji 《虛雲和尚全集》 (A Collection of Master Hsu-Yun’s Works). volume 2. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House, 2009. p. 135.Qisha Canon Engraved during the Song and Yuan Dynasties by Photocopy Edition, 《影印宋元版磧砂大藏經》, vol. 116. Published by Beijing: Thread-Bound Book Press, 線裝書局, 2005.National Library of China 中國國家圖書館, and China National Center for the Protection of Ancient Books 中國國家古籍保護中心, eds. 2010. Diyipi Guojia Zhengui Guji Minglu Tulu 《第一批國家珍貴古籍名錄圖錄》 (the antique catalog of first National Rare Ancient Book Directory). Beijing: Guojia Tshuguan Chubanshe, vol. 3.National Library of China 中國國家圖書館, and China National Center for the Protection of Ancient Books 中國國家古籍保護中心, eds. 2012. Dierpi Guojia Zhengui Guji Minglu Tulu 《第二批國家珍貴古籍名錄圖錄》 (the antique catalog of second National Rare Ancient Book Directory). Beijing: Guojia Tshuguan Chubanshe, vol. 2.Secondary Sources

- Chen, Binqiang 陳彬強, Donglong Chen 陳冬瓏, and Wanying Wang 王萬盈, eds. 2020. Quan zhou hai shang si chou zhi lu li shi wen xian hui bian chu bian 《泉州海上絲綢之路歷史文獻匯編初編》 (The First Compilation of Historical Documents on the Quanzhou Maritime Silk Road). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, pp. 595–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhiping 陳支平, and Shichuang Zhan 詹石窗. 2003. Tou shi zhong guo dong nan 透視中國東南 (Insight into Southeast China). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Zhangcan 程章燦. 2022. Shi kewenxian zhi “sibenlun” 《石刻文獻之“四本論”》 (The Four Versions of Stone Inscription as Literature). Journal of Sichuan University Philosophy and Social Science Edition 5: 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Fanyu 戴蕃豫. 1995. Zhong guo fo dian kan ke yuan liu yan jiu 《中國佛典刊刻源流考》 (Spreading of Chinese Buddhist Canon Carving Origin). Beijing: Bibliography and Document Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Meiling 鄧美玲. 2005. Zhongguo chanzongyou chanzong suyuan zhilv 《中國禪宗遊·禪宗溯源之旅》 (Travels of Chinese Zen Buddhism: Journey to Trace the Origin of Zen). Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Hui 梵輝. 1985. Fu jian ming shan da si cong tan 《福建名山大寺叢談》 (Conversations on Famous Mountains and Grand Temples in Fujian). Fuzhou: Fujian Yixian Art Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Haar, Barend ter 田海. 2017. Zhong guo li shi shang de bai lian jiao 《中國歷史上的白蓮教》 (The White Lotus Society in Chinese History). Translated by Rui Wang, and Ping Liu. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Mei 何梅. 2005. Beijing zhihuasi yanyouzang ben kao 《北京智化寺元<延祐藏>本考》 (An Examination of the Yanyou Canon of Yuan Dynasty in Beijing Zhihua Temple). Studies in World Religions 2005: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Zhongzhao 黃仲昭. 1991. Ba min tong zhi 《八閩通志》 (Bamin Annals, in Fujian Local Chronicles Collection). Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House, vol. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Hui 淨慧, ed. 2009. Xuyunheshangquanji 《虛雲和尚全集》 (A Collection of Master Hsu-Yun’s Works). Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 2, p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fuhua 李富華, and Mei He 何梅. 2003. Hanwen fojiao dazangjing yanjiu 《漢文佛教大藏經研究》 (Research on Chinese Canon). Beijing: China Religions Culture Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Kan’ichi 小川貫弌. 1943. Carved Stories of Bai Lianjiao in the Yuan Dynasty. Chinese Buddhist History 7: 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Kan’ichi 小川貫弌, and Ziqing Lin 林子青. 1988. Wuxing miao yan si ban zang jing za ji 《吳興妙嚴寺版藏經雜記》 (Miscellaneous Records of the Canon Printed at Miaoyan Temple in Wuxing). The Voice of Dharma 1988: 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Wensen 潘文森, and Cuncheng Chen 陳存誠. 1995. Fuzhou shihuacongshu feng ming sanshan 《福州史話叢書·鳳鳴三山》 (Fuzhou History Series: The Singing of the Phoenix to Fuzhou). Fuzhou: Fuzhou Evening News福州晚報社, pp. 220–21. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Lian 宋濂, Kekuan Wang 汪克宽, Han Hu 胡翰, Xi Song 宋僖, Kai Tao 陶凯, Ji Chen 陈基, Xun Zhao 赵壎, Lu Zeng 曾鲁, Wenhai Zhang 张文海, Zunsheng Xu 徐尊生, and et al. 2013. Yuan shi 《元史》 (The Yuan Dynasty History). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company 中華書局, pp. 3198–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tiefan 王鐵藩. 1995. Min du cong hua 《閩都叢話》 (Conversations on Mindu, Fuzhou: Haichao Photography Art publishing House). Fuzhou: Ocean Tide Photography Art Publishing House 海潮攝影藝術出版社, pp. 431–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Xiaowang 徐曉望. 2023. Yuan dai Fu jian shi 《元代福建史》 (History of Fujian in the Yuan Dynasty). Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ne 楊訥. 1989. Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu ziliao hui bian 《元代白蓮教研究資料匯編》 (Compilation of Research Materials on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ne 楊訥. 2017. Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu 《元代白蓮教研究》 (Research on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty). Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- You, Biao 游彪. 2011. foxing yu renxing:songdai minjian fojiao xinyang de zhenshi zhuangtai 《佛性與人性:宋代民間佛教信仰的真實狀態》 (Buddhist Nature and Human Nature: The True Status Quo of Buddhist Belief among the People in the Song Dynasty). Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science) 2011: 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiumin 張秀民. 2006. Zhongguo yinshuashi 《中國印刷史》 (Zhang Xiumin history of Chinese Printing). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi 祝熹. 2019. Xi chu que li, yun shui tao yuan 《西出闕里,雲水桃源》 (Leaving Queli in the west, going into a haven of clouds and waters). Fuzhou: Straits Book Company Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

| Volume | Serial Numbers Based on the Engraving Records | Colophon |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Long 龍 | 黃州路麻城縣龔氏妙真、劉顯祥、陳氏妙清、林德廣、胡仲勝、程普壽、水氏一娘、朱大哥、熊覺明、李覺福、那氏五娘、鄒氏一娘、宮文仲、王氏妙法、楊氏妙義,已上各刊一紙,共成一卷,報資恩有者。 |

| Gong Mizhen, Liu Xianxiang, Chen Miaoqing, Lin Deguang, Hu Zhongsheng, Cheng Pushou, Shui Yiniang, Brother Zhu, Xiong Jueming, Li Jiaofu, Na Wu Niang, Zou Yiniang, Gong Wenzhong, Wang Miaofa, and Yang Miaoyi from Macheng County, Huangzhou Road. Each engraved one sheet, collectively completing one volume to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 18 | Shi 師 | 陸安州陸安縣晏覺燈同妻子丁氏妙明共刊五紙,周覺力刊五紙,劉氏妙持同夫鄒覺悔共刊二紙,高覺海刊一紙,共成一卷,報資恩有者。 |

| Yan Juedeng from Lu’an County, Lu’an Prefecture, with his wife Ding Miaoming, engraved five sheets. Zhou Jueli engraved five sheets. Liu Miaochi, with her husband Zou Juehui, engraved two sheets. Gao Juehai engraved one sheet. Altogether, they completed one volume to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 20 | Shi 師 | 光州固始縣李覺性、胡氏三娘各刊二紙,祝有才、李誠、張漢用各刊一紙,帥氏妙清刊半紙;陸安州陸安縣吳明祖同妻吳氏五娘、周氏妙新、周覺願、胡氏四娘、尤德明、李覺廣、朱氏七娘,已上各刊一紙,共成一卷,上報四恩,下資三有。 |

| Li Juexing and Hu Sanniang from Gushi County, Guangzhou, each engraved two sheets. Zhu Youcai, Li Cheng, and Zhang Hanyong each engraved one sheet. Shuai Miaoxing engraved half a sheet. Wu Mingzu from Lu’an County, Lu’an Prefecture, with his wife Wu Wu Niang, Zhou Miaoxin, Zhou Jueyuan, Hu Siniang, You Deming, Li Jueguang, and Zhu Qiniang, each engraved one sheet. Altogether, they completed one volume to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above and benefit the Three Realms below. | ||

| 29 | Huo 火 | 建昌州控鶴鄉津濟堂周覺布、男周覺德舍刊一函報資恩有者。 |

| Zhou Juebu and his son Zhou Juede from Jinji Hall in Konghe Country, Jianchang Prefecture, donated the engraving of one set of scriptures to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 50 | Wu (烏) | 江西道贛州人謝覺戒施三十兩,僧久珩、謝妙心、宋覺會、四會鄉大安里居何逢元、劉覺直、李八都居住溫才英、李氏三各施十兩,共中統三定,刊經一卷。上報四恩,下資三有,惟願世世生生同生淨土者。 |

| Xie Juejie from Ganzhou in Jiangxi Circuit donated thirty taels of silver. Monks Jiuheng, Xie Miaoxin, Song Juehui, and He Fengyuan from Da’anli, Sihui Country, Liu Juezhi, Wen Caiying from Li Badu, and Li Shisan each donated ten taels of silver. Together, they donated three ding of Zhongtong banknotes and engraved one volume of scriptures, hoping to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above, benefit the Three Realms below, and be reborn in the Pure Land. | ||

| 59 | Guan 官 | 河南江北道汴梁省汝寧府光州固始縣回龍山古心堂陳覺圓募眾喜舍四十五定,謹刊斯經一十五卷,上報四恩,下資三有者。 |

| Chen Jueyuan from Guxin Hall on Huilong Mountain in Gushi County, Guangzhou, solicited donations from the public and received forty-five ding in contributions. He carefully engraved fifteen volumes of these scriptures to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above and benefit the Three Realms below. | ||

| 83 | Shi 始 | 江西撫州崇仁寧克伸舍刊一卷,祈薦父母宗親,超生淨界者。 |

| Ning Keshen from Chongren, Fuzhou, Jiangxi, donated the engraving of one volume of scriptures, praying for his parents and relatives to be reborn in the Pure Land. | ||

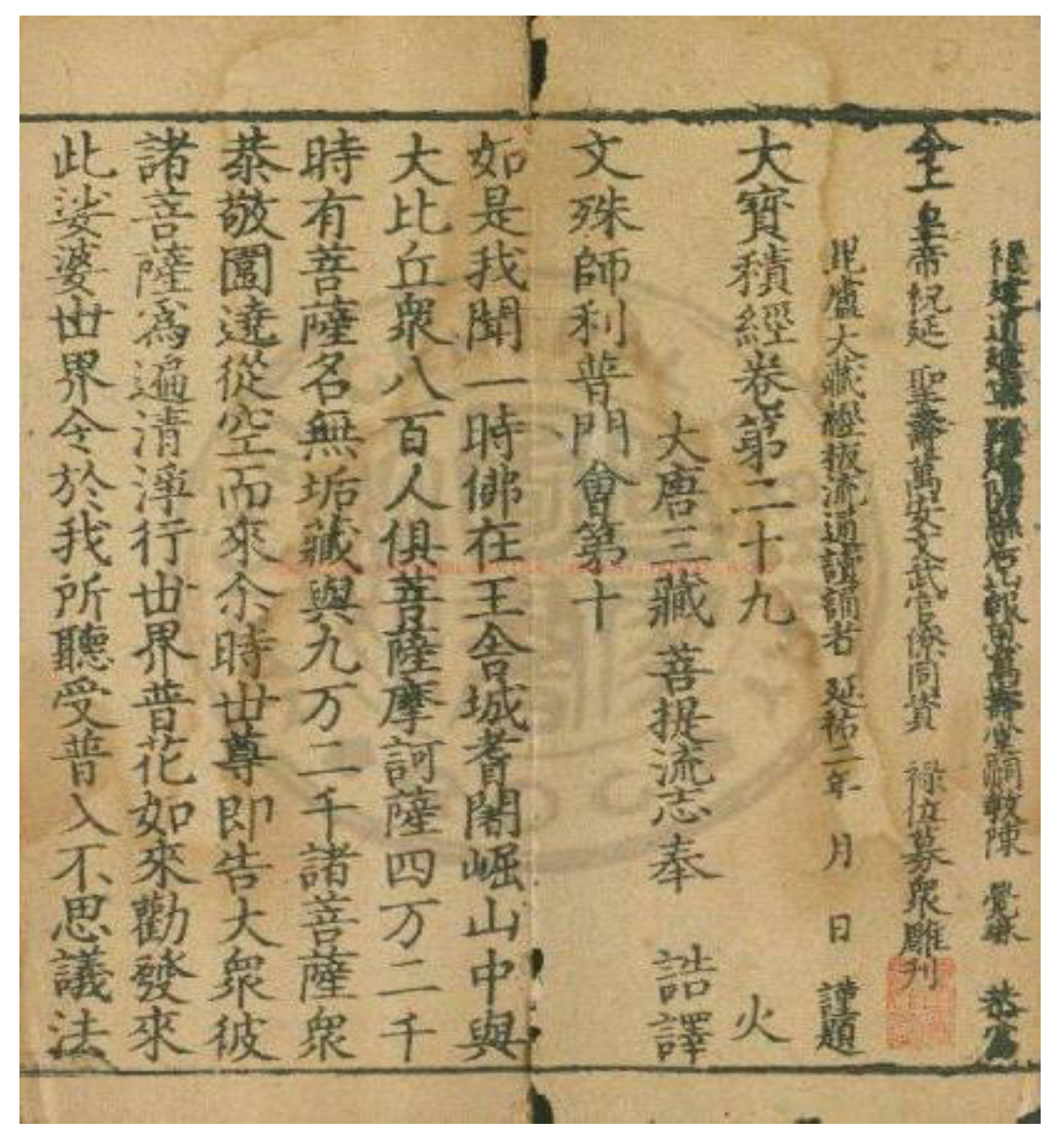

| 84 | Shi 始 | 福建道建寧路建陽縣後山報恩萬壽堂嗣教陳覺琳,恭爲今上皇帝,祝延聖壽萬安,文武官僚同資祿位,募眾雕刊《毗盧大藏經》板,流通讀誦者,延祐二年 月 日謹題。 |

| Chen Juelin of Bao’en Wanshou Hall in Houshan Village, Jianyang County, Jianning Road, Fujian Circuit, solicited public donations to carve the printing blocks of the Buddhist Canon, praying for the eternal longevity of the emperor and prosperity for distinct and military officials. Respectfully inscribed in the second year of the Yanyou reign. |

| The Standard Form | The Vulgar Forms of the Song Pilu Canon | The Vulgar Forms of the Yuan Pilu Canon |

|---|---|---|

| 藏 |  |  |

| 軟 |  |  |

| 多 |  |  |

| 差 |  |  |

| 復 |  |  |

| 教 |  |  |

| 切 |  |  |

| 往 |  |  |

| 厭 |  |  |

| 此 |  |  |

| 比 |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, T. The Publication and Dissemination of the Yuan Dynasty Pilu Canon. Religions 2025, 16, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050650

Zhao T. The Publication and Dissemination of the Yuan Dynasty Pilu Canon. Religions. 2025; 16(5):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050650

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Tun. 2025. "The Publication and Dissemination of the Yuan Dynasty Pilu Canon" Religions 16, no. 5: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050650

APA StyleZhao, T. (2025). The Publication and Dissemination of the Yuan Dynasty Pilu Canon. Religions, 16(5), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050650