Abstract

In this paper, I investigate the phenomenology of awakening in Chinese Zen Buddhism. In this tradition, to awaken is to ‘see your true nature’. In particular, the two aspects of awakening are: (1) seeing that the nature of one’s self or mind is empty or void and (2) an erasing of the usual (though merely apparent) boundary between subject and object. In the early Zen tradition, there are many references to awakening as chopping off your head, not having eyes, nose and tongue, and seeing your ‘Original Face’. These references bear a remarkable resemblance to an approach to awakening developed by Douglas Harding. I will guide the reader through a series of Harding’s first-person experiments which investigate the gap where you cannot see your own head. I will endeavour to show that these methods, although radically different from traditional meditation techniques, result in an experience with striking similarities to Zen accounts of awakening, in particular, as experiencing oneself as empty or void and yet totally united with the given world. The repeatability and apparent reliability of these first-person methods opens up a class of awakening experience to empirical investigation and has the potential to provide new insights into nondual traditions.

1. Introduction

A prominent thread in Asian thought, found in such traditions as Advaita Vedanta and Zen Buddhism, is that our everyday human experience has the character of a dream. The dream is that you are merely a person—a thing in the world bounded by your skin, a self that is separate from things and other people. A modern presentation of this theme is the movie The Matrix, in which Neo is not sure if the world is real or merely a dream. While it turns out that Neo also has a body in the real world, this was certainly not guaranteed. If you were merely dreaming that you were in this body, would you, like Neo, be daring enough to awake and see yourself as you really are?1

Here I will focus on awakening in Chinese Zen Buddhism (Chan). The raison d’être of Zen is to see through the delusion of being a bounded separate thing and to fully actualise this awakening in one’s everyday life (Kapleau 2000, p. 55). Having said this, it is important to qualify that one does not intentionally strive for awakening in one’s Zen practice, rather the practice itself is the goal (Kapleau 2000, p. 137). This self-realisation is referred to as ‘Kensho’, which literally means ‘seeing one’s true nature.’2 I interpret ‘true nature’ as meaning the same as essential or intrinsic nature. Combined with the Buddhist doctrine that ‘you’ have no essential or intrinsic nature at all, Kensho would be a seeing that you are essentially empty of separate self-existence (Garfield 2014, chp. 3).3

‘Bodhi’ translates as ‘awakening’ and ‘Buddha’ as ‘awakened’. I use the term ‘awakening’ here in the narrow sense of Kensho.4 I avoid the terms ‘Enlightenment’ and ‘enlightened’ due to their association with a final permanent state and morally perfect individuals.5 Unfortunately, as we know from experience, there have been a significant number of ‘enlightened’ masters in Western Buddhist centres engaging in sexual misconduct. For those who have faith in enlightenment this is an uncomfortable mystery (Domyo 2019). There were also many purportedly enlightened Japanese Zen masters who fought in World War II and used their Zen training to kill more effectively (Victoria 1997). A Kensho experience, by contrast, does not require being morally good, nor is virtuousness an inevitable outcome of the experience. Seeing one’s identity with others is the basis for true compassion, but integrating this and other insights into everyday life is the unending work of a lifetime (Kapleau 2000, pp. 67–68).

Awakening is a transformation in how one experiences oneself and the world. While Kensho is unique to every individual, two main indivisible aspects can be identified. The first aspect is seeing that the nature of one’s self or mind is empty or void. Shen-Hui (684–758), a student of Hui Neng stated ‘Seeing into one’s Self-Nature is seeing into Nothingness. Seeing into Nothingness is true and eternal seeing’ (Suzuki [1949] 1969, p. 30). The second aspect is the erasing of the usual (though merely apparent) boundary between subject and object. Huang-Po (d. 850) described it as ‘a perception, sudden as blinking, that subject and object are one’ (Blofeld 1958, p. 92)6

How exactly does one see their true nature? Douglas Harding developed a method of self-inquiry (the Headless Way), that can be considered a modern method of awakening. The method uses apparatus to orient attention to who or what you are in your own first-person experience, hence it may be referred to as a ‘technology of awakening’. The key to this method is noticing that you cannot see your own head. Rather than looking out of a head, visually speaking, there is just a gap here. This is perhaps the most overlooked spot in the world. References to ‘headlessness’ are scattered throughout early Zen literature. When Zen master Qinggan was asked how the sages of old had obtained awakening, he replied by making a motion as if chopping off his own head (Daoyuan 2016, p. 173). Although T’ieh-Shan had made considerable progress in his practice, Zen Master Yeng recommended the need for ‘a good hammer-strike to the back of [his] head’ (Chang 1957, p. 341). Harding describes his own vivid experience of ‘headlessness’ in the Himalayas:

What actually happened was something absurdly simple and unspectacular: just for the moment I stopped thinking. Reason and imagination and all mental chatter died down. For once words really failed me. I forgot my name, my humanness, my thingness, all that could be called me or mine. Past and future dropped away. It was as if I had been born that instant, brand new, mindless, innocent of all memories. There existed only the Now, that present moment and what was clearly given in it. To look was enough. And what I found was khaki trouser legs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in—absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head. It took me no time at all to realise that this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the contrary, it was very much occupied. It was a vast emptiness vastly filled, a nothing that found room for everything—room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far above them snow peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world.(Harding [1986] 2000, pp. 1–2)

This is of course a phenomenological description. It is not the claim that the person Douglas Harding does not have a head. If attending here is a way of awakening, then where I am looking from would be like a gap in the Matrix,7 and hence it bears careful investigation. To explore this further, I will guide the reader through some first-person experiments pioneered by Douglas Harding. Although the methods are radically different to traditional meditation techniques, the results converge with descriptions of awakening from contemplative traditions. Here, I will focus on how they illuminate accounts of awakening in Chinese Zen and vice versa.8 As my main goal is to investigate the phenomenology of awakening rather than metaphysics, for the most part, I will be neutral about whether such experiences, and the phenomenology explored here, directly reveal reality. Although, I use the term ‘awakening’ throughout, this should be taken as short for ‘awakening experience’ and hence as neutral about the epistemological and metaphysical implications of the experience.9 I briefly present the case for the experience representing a genuine awakening in Section 9.

2. Experimental Phenomenology

The method of this article is quite different to that of traditional Buddhist scholarship. Scholarship is typically the analysis and interpretation of primary texts and an attempt to derive a theory or meaning that is consistent across parts of a text or a body of texts. In this approach, the primary evidence is the text. By contrast, the method of this article is phenomenological. The primary evidence is experience itself. The goal is to show how Zen Buddhist descriptions of awakening cohere with specific phenomenological data and how these experiences illuminate the meaning of Zen texts. Rather than textual analysis, the current method is phenomenological. If we think of Zen texts as analogous to instructions for baking a cake, scholarship of these texts will only focus on the texts and try to derive the best possible recipe. The experimental phenomenological approach on the other hand derives basic guidance from the recipe and then actually tries to bake the cake. Contrary to appearances, scholarship is not avoided in Zen. Studying the Sutras is an important part of practice (Chang 1957, pp. 334–38; Wright 2000, chp. 2). However, pure scholarship, where one never gets around to baking and eating the cake, is antithetical to the spirit of Zen.

The innovation of using experimental phenomenology is that resulting experience can then be used to shed new light on these ancient instructions. The claims in the instructions can actually be tested out to see if they work in real life. The current approach is hence reconstructive rather than purely interpretative. It is analogous to reconstructive archaeology which tests theories about cultural artefacts by attempting to build those very artifacts using technologies and materials that were available at the time. Some knowledge can only be gained by doing.

The risk of reconstructive phenomenology is that the experience may be quite different to the original. On the other hand, as Zen texts are centuries old and from a different culture and language (at least to my own), they are already subject to many types of distortions—historical, cultural, translative. If the goal of the texts is to change one’s lived experience (at least this is how they are approached by contemporary practitioners), it is reasonable to hold that a phenomenological approach can provide insights about the texts and vice versa.10 This being said Zen Buddhist scholars are highly critical of the modernist assumption, such as professed by D. T. Suzuki, that the primary focus of Chan was personal experience.11 It can at least be claimed though that the current paper identifies intriguing parallels between the current phenomenological approach and Zen texts.

3. Awakening in Zen

When the uneducated kitchen boy Hui Neng (638–713) received the Dharma succession of the Fifth Patriarch, the other monks were furious. Although illiterate, Hui Neng, had directly seen the essence of Mind. He showed his intuitive knowledge of his self-nature by defeating Shen-Hsiu the head monk in a competition to compose a stanza on the Dharma. Shen-Hsiu’s stanza read:

Our body is the bodhi tree,

And our mind a mirror bright,

Carefully we wipe them hour by hour,

Hui Neng’s stanza read:And let no dust alight. (Price and Wong 1990, p. 70)

There is no bodhi tree,

Nor stand of mirror bright.

Since all is void,

Where can the dust alight? (Ibid., p. 72)

Hui Neng’s stanza was superior because it exhibited no duality. It avoided the mistake of believing that the goal of practice is to empty one’s mind so that the Void can shine forth. It also shows as Hui Neng later realised, that the void is intrinsically pure and so cannot be obscured by thoughts.12

Having seen Hui Neng’s potential, the Fifth Patriarch invited Hui Neng to meet secretly and expounded the Diamond Sutra to him. This triggered a great awakening. Hui Neng exclaimed in ecstasy:

Who would have thought that the essence of mind is intrinsically pure! Who would have thought that the essence of mind is intrinsically free from becoming or annihilation! Who would have thought that the essence of mind is intrinsically self-sufficient! Who would have thought that the essence of mind is intrinsically free from change! Who would have thought that all things are the manifestation of the essence of mind!(Ibid., p. 73)

On this basis, the Fifth Patriarch gave Hui Neng the robe and bowl of succession. This led to a chase scene, famous in the history of Zen. Hui-Neng fled across the country side pursued by hundreds of angry monks. Finally, one of the monks, Wei Ming, caught up with him. Hui Neng threw down the robe and bowl. It is reported that when Wei Ming tried to pick up the robe and bowl he could not. Wei Ming then said ‘I come for the Dharma not the robe and bowl.’ Hui Neng’s life quite likely depended upon what he said next, so he had to communicate the essence of Zen right there and then. Hui Neng asked:

When you are thinking of neither good nor evil, what is at this particular moment, venerable sir, your Original Face?’ As soon as Wei Ming had heard this he at once became enlightened. But he further asked, ‘Apart from those esoteric sayings and esoteric ideas handed down by the patriarchs from generation to generation, are there any other esoteric teachings?’ ‘What I can tell you is not esoteric,’ Hui Neng replied. ‘If you turn your light inwardly, you will find what is esoteric within you.(Ibid., pp. 75–76)

In Zen, one’s Original Face is used interchangeably with one’s True Nature or Buddha Nature. One sees it by attending within, that is by reversing one’s attention from the objects of consciousness (including from one’s thoughts). This inward look is referred to as ‘the backward step’, ‘turning inwards’ and ‘turning back’.13 Hongzhi (1091–1157) instructed his followers to ‘take the backward step and directly reach the middle of the circle from where light issues forth’ (Leighton 2000, p. 40). Dogen (1200–1253) in his Fukanzazengi, Universal Recommendation of Zazen, wrote:

You should therefore cease from practice based on intellectual understanding, pursuing words and following after speech, and learn the backward step that turns your light inwardly to illuminate your self. Body and mind of themselves will drop away, and your original face will be manifest. If you want to attain suchness, you should practice suchness without delay.(Dogen 2010, p. 3)

Kensho can take place suddenly, at any time. Meditation can assist this sudden awakening, but it can also happen spontaneously without any meditation experience at all. You can see your original nature right here and right now whether you are thinking or not. Detailed instructions for looking inwards will be given below. First, however, we will see how Zen describes your true nature.

4. What to Look For

Having survived his ordeal, many years later Hui Neng had established a large monastery. He addressed a large audience of eagerly listening monks on their true nature:

The capacity of the mind is as great as that of space. It is infinite, neither round nor square, neither great nor small, neither green nor yellow, neither red nor white, neither above nor below, neither long nor short, neither angry nor happy, neither right nor wrong, neither good nor evil. Learned Audience, the illimitable Void of the universe is capable of holding myriads of things of various shape and form, such as the sun, the moon, stars, mountains, rivers, worlds, springs, rivulets… Space takes in all these and so does the voidness of our nature.(Price and Wong 1990, p. 80)

Similarly, Hui Hai (720–814) stated: “Mind has no colour, such as green or yellow, red or white; it is not long or short; it does not vanish or appear; it is free from purity and impurity alike; and its duration is eternal. It is utter stillness. Such then is the form and shape of our original mind, which is also our original body.” (Blofeld [1962] 2007, p. 47) Our true nature, then, is like a void. It lacks all objective qualities. It is shapeless, colourless, limitless, changeless, beyond size, and contains all things.

5. The Science of the First-Person

The following methods are awareness exercises developed by Douglas Harding. The goal of the methods is to contrast what it is like to be you in your first-person experience with how you appear to others. To do this one must have the scientific attitude of openness to how things are given, rather than how you think, imagine or believe they are.

First-person approaches have been strongly criticised for their unreliability as scientific methods (Dennett 1991, 2018; Irvine 2012; Schwitzgebel 2011). Although there is some truth to these criticisms, I hold that they either overlook or downplay the reliability of first-person experiments in the history of psychology. These methods are common in illusion research and Gestalt psychology. In these approaches, subjects are presented with different stimuli and asked how things look or seem. In particular, they are asked to carry out simple phenomenal contrasts (i.e., identify a phenomenal difference) in different conditions. The current awareness exercises can also be considered first-person experiments in that they use apparatus to assist subjects to make a phenomenal contrast. Elsewhere, I defend the reliability of such methods and how they overcome two main introspective errors: 1. Attentional: Errors in directing attention and 2. Conceptual: Errors in employing the correct concept in making a judgement about an experience (Ramm 2018).14

The techniques can be understood as a form of radical empiricism. In this they agree with the spirit of Zen, or at least that of many contemporary forms of Zen. As D. T. Suzuki put it:

Zen is emphatically a matter of personal experience; if anything can be called radically empirical it is Zen. No amount of reading, no amount of teaching, no amount of contemplation will ever make one a Zen master. Life itself must be grasped in the midst of its flow; to stop it for examination and analysis is to kill it, leaving its cold corpse to be embraced.(Suzuki [1954] 1981, p. 132)

This reliance upon one’s own experience is also advocated by the venerated master Huang-Po who said, ‘Observe things as they are and don’t pay attention to other people’ (Blofeld 1958, p. 54). It is important then that you actually do the experiments, otherwise this article will not make any sense. As I mentioned in the introduction, the basic observation from which we begin is that you cannot see your own head.

There are many examples of using this observation as a way into Zen. When Hui Hai was asked by a visiting scholar about how he taught, he replied that he had no tongue to urge people to do anything. The visitor was confused and asked ‘Why, Master are you lying to my face?’ Hui Hai replied ‘How can this old monk being without a tongue to urge people, tell a lie?’ The exasperated philosopher exclaimed ‘Really I do not understand the way the Venerable Chan Master talks.’ Hui Hai replied ‘Nor does this old monk understand himself’ (Blofeld [1962] 2007, pp. 130–31)15. The philosopher, an expert in words and concepts, totally failed to notice his own first-person experience. From where indeed does your voice issue forth in your own direct experience? Huang Po also pointed to the absence here. In particular, he asserted that awakening involves ‘realising that though you eat the whole day, no single grain has passed your lips’ (Blofeld 1958, p. 131). Indeed, do you eat by putting food into a mouth in your direct experience, or into a void? This is an empirical question. Where does the flavour actually occur? Huang-Po also observed that even though his travelling hat is small ‘the entire cosmos is readily covered underneath’ (Suzuki [1949] 1969, p. 105). As these examples from the history of Zen show, if anything, the main barrier to realising one’s essential nature is that it is too simple and obvious. We investigate the ‘headless’ experience further in the following experiments.

6. Experiments in Zen Phenomenology

6.1. The Single Eye

How many eyes are you looking out of in your present experience? Are you looking out of two small portholes in a thing, or a single open space? To investigate this, you will need to make a pair of glasses with your fingers—or use your actual glasses if you have some. Hold out your glasses in front of you. Notice the two holes in the frames and how each contains a part of the room. Additionally, notice that the frames are opaque—you cannot see through them. Are there two holes where you are looking from? To test this, bring your glasses towards where other’s see your face. Notice that the frames grow larger. Each contains more and more of the room. Slowly bring them right up and put them on. Notice that when you do this the boundaries between the two holes blur and then disappear. My experience is that my glasses transform into a monocle.16 Let your fingers drop and notice that what you are looking out of has no glass or frame. In fact, it is not bounded by anything.17 I seem to be looking out of a single open ‘space’ here.18 We can call this our ‘Single Eye’.19

In the history of Zen, when asked ‘what is the Tao?’ Zen master Yichu replied by opening his arms to the scene (Daoyuan 2016, p. 183). Please do so right now. Put your arms out and trace out the edges of the visual field. Is there anything outside of the view? Notice that your hands blur and then disappear past the edges.

This open space is not in anything. It has no boundary. If I shift my gaze, I see further things, but these things also move into the view. The view itself never has anything sensorily outside of it.20 This is analogous to what is presented on a television screen when it is ‘scanning’ over a scene. The screen itself does not move, rather the scene moves.21 Recall, that according to Zen your true nature has no limits nor any size. I can compare the size of two chairs by putting them next to each other. However, there is no second Gap to compare this one to. As such, size cannot be applied to it. Just as there are no boundaries around the Space that I’m looking from, there is no boundary between it and the scene. There is absolutely nothing here to get in the way of the scene. When I look for my head, I find the world.

6.2. The Pointing Experiment

The essential teaching of Zen is summarised by a verse attributed to Bodhidharma (5th or 6th Century), the First Patriarch of Zen:

A special transmission outside the scriptures,

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to one’s mind

It lets one see [into one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.(Dumoulin 2005, p. 85)22

How does one directly point to one’s mind or true nature as urged by Bodhidharma? How exactly does one look within? Eyes cannot look backwards, but one’s attention can be pointed in any direction. The pointing experiment assists one to turn their attention within by using a pointing finger to literally point to the spot you are looking from. Please do the following:

Point at a distant thing such as a wall. Notice its shape and colour. It is a thing that is extended in space. Notice that it is opaque. You cannot see through it. Now point to the floor. Again, notice the coloured expanse and its textures. Now point to your foot. Again, it is a shaped and coloured thing. Point to your chest and notice its colours and shape and the movement from your breathing. Now point to where you are looking from. In your present experience are there any colours here? Any shape? Any texture? Any movement? Are there any eyes, mouth, or cheeks here? Are there any features of person? Notice that this spot is totally lacking in any personally identifying characteristics. Is there anything at all here? Or is it just a transparent opening?23

Notice that there is a blur which you usually call your nose. Notice how big it is. It stretches from the top to the bottom of the scene. I find that it is constantly switching from one side to the other or disappearing altogether. Whatever you want to call it, this is quite unlike what you find in the middle of someone’s face. In any case, it is the unbounded Gap here that we are interested in.

When I look within, that is turn my attention 180 degrees from objects over there to where I am, I find that I am not a coloured, limited thing in the world, but rather a colourless unbounded capacity for the world. Miraculously, this is not a dead void, but awake to itself, the finger and the scene. Is this true for you? In fact, as there is no dividing line between the ‘container’ and the ‘contents’, it would be more accurate to say, using a common Buddhist metaphor, that given reality itself is self-luminous (Harding [1986] 2000, p. 2).

6.3. The Mirror Experiment

Once as a child, Tung-Shan (807–869) was studying the Heart Sutra with his tutor when he came to the passage ‘no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind.’ He was confused. He used his hands to feel his face and then asked his tutor why the Sutra said they did not exist. His tutor told Tung-Shan that he could not help him. Tung-Shan spent many years searching for a worthy master to explain this and other mysteries of the Dharma to him. Finally, one day he was crossing a river and saw his face reflected in the water. He saw where his face was in his lived experience and he instantly had a great awakening (Tung-Shan 1986, pp. 23–27).

Zen goes beyond words and letters, so merely thinking about Tung-Shan’s story would be against the spirit of Zen, not to mention science. To test it out directly in your own experience, please carry out the following experiment:

Look into a mirror. You can now see your human face. Notice where it is. It is over there a couple of feet away, not on your shoulders. It is also facing the wrong way. It is looking in, rather than outwards. How many faces do you see? Two or one? Notice the shapes, textures and colours of that little face trapped behind the glass. By contrast, notice the lack of shapes, textures, colours and indeed boundaries to the spot you are looking from. That face over there is your acquired face (Harding [1990] 1999, p. 65). When you were an infant you did not recognise it as your own. It was just a baby behind some glass. It took many months to learn to identify with that face. Presumably you learnt to marry that visual thing over there with the ‘facial’ sensations you feel here, and hence you became boxed in (at least apparently so). Is not how you are for yourself a total contrast to that little face in the mirror? That face over there is always changing. It was once a smooth child’s face. For me it is now a middle-aged man’s face with wrinkles around the eyes and greying sideburns. By contrast, has the Space you are looking out of aged at all? Are there any characteristics here that could wither and die? Is it any wonder if you often do not feel any older than when you were a child and are sometimes shocked by how your body has aged? That is merely how you appear to others. Seeing here is like having the ultimate face lift. My Original Face is always the same—its complexion is always perfectly spotless.24

6.4. The Spinning Experiment

As we saw earlier, according to Zen your original nature is totally motionless. To test this claim, stand in the centre of a room and point outwards. Now slowly turn on the spot. From present experience are you turning or is the room turning? Notice the door, window and other objects move past your motionless pointing finger. Keep turning, but now point at where others see your face. By contrast, is what you are pointing at moving or still? Are you not currently the still centre of that turning world? Would you say that this Stillness is full of motion? Now stop spinning and slowly walk around the room. Notice the objects moving through your still consciousness and bobbing up and down at every step. We can understand from direct experience then how Huang-Po can say that ‘a day’s journey has not taken you a single step’ (Blofeld 1958, p. 131). Similarly, we can see why in a beginner’s Koan, Mahasattva Fu claims that when I cross a bridge it is the bridge that flows, not the water (Cleary and Cleary [1977] 2005, p. 528). These apparently paradoxical statements suddenly make sense when read phenomenologically.25

6.5. Closed Eye Experiment

We have found so far that though you appear as a thing to others (and to yourself in mirrors), for yourself where you are looking from you are non-thing-like. What about other senses? To test whether this finding also applies to other senses please carry out the following awareness exercise:

Close your eyes (or more accurately your Single Eye from your perspective). Notice the room disappear and become replaced by darkness. Attend to your bodily sensations. What shape are those sensations? How many toes do you feel? Are there two feet shaped things or are there shapeless sensations that you associate with feet? Do the sensations form a precise body outline? How many ears do you have? Is there a precisely shaped nose? Would you know what a face was shaped like if you had never seen or touched one? Try touching your face. Notice that you can now feel distinct, squishy contours. Do you feel a precisely shaped face all at once? Or do you lose whatever you are not touching? Are you in those sensations or are they in your awareness? Now attend to sounds. Voices, a computer humming, bird calls, cars beeping, foot-steps. Notice how you imagine what those things are. Are the sounds outside of you? Is there any inner-outer division on present evidence? Or are they occurring in an unbounded silent awareness? What is your age on present evidence? What is your name? If you are a person, what kind of person are you? Are not all of the answers to these questions just further thoughts and images in your awareness? Are bodily sensations, sounds, thoughts and images in separate fields, or are they occurring in a single awareness? Now open your Single Eye. Notice the vivid colours and shapes of the room. Are your thoughts and images back in a headbox, or are they at large in the room?26

7. The Nonduality of Subject and Object

Recently, watching the sunset over the Swan River in Perth, I saw vividly that the vast black and orange rippling expanse of water was my own face. Thoughts and feelings also arose and that was okay. They were also part of the scene. Although the splendour no doubt helped to erase the usual sense of separation, I give this as an example not of a mystical experience, but of a perfectly natural and in fact ordinary experience. It is commonplace to be absorbed in watching movies, playing sport, riding a bike, or reading a book—even writing an article. I’m sure that the other transfixed onlookers also experienced something similar to me, even if they were not aware of their no-face. Non-separation is not the privileged domain of contemplatives, but an everyday experience.

From the first-person perspective, perception is not a relation between ‘me’ and other things. As nothing here in myself, I am what I see, hear and feel. Things are experienced as me rather than for me (Fasching 2008, p. 479). It is understandable then, that according to Zen, you are not just a bare void, but everything is your True Face. To awaken is to swallow all of the West River in one gulp (Kapleau 2000, p. 199). It is to be the one ‘whose robe is cut out of mists, clouds and dews.’27 We can add that this is already everyone’s natural condition, just not everyone notices it. There is nothing to attain and there is certainly nothing spiritual or mystical about it.

There are numerous examples of Zen of masters answering a question about the Dharma by pointing to something in nature. When a monk asked ‘What is the heart of the ancient Buddhas?’ Zen Master Zhensui replied: ‘Mountains, rivers and the great earth.’ (Daoyuan 2016, p. 196). The nonduality of self and the world is also available via other senses. When a monk asked the way into Zen, Master Gensha (835–908) replied ‘Do you hear the murmuring sound of the stream?’ The monk answered, ‘Yes, I do.’ The master said, ‘Here is the entrance.’ (Suzuki 1956, p. 251).

As totally empty, your Original Face is the vast scene. This void has no properties of its own and so is perfectly united with the world (Harding [1986] 2000, p. 60; Harding 2000, p. 65). Is this how it is for you? It is perhaps understandable then that in Zen we are told that your true nature is beyond all dualities such as emptiness and fullness, purity and impurity, stillness and motion. As the Heart Sutra describes it, ‘form is emptiness, emptiness is form’. Another way of putting it is: looking inwards I am nothing, looking outwards I am everything on show. Alternatively, I am an empty-fullness. These paradoxical phrases will not please philosophers, however they point to an experience that goes beyond dualistic conceptual categories. Perhaps, then, a simple identity of subject and object is the best description of the experience of awakening? While representing a great insight, I submit that even the Buddhist doctrine that emptiness is identical with form is not quite phenomenologically adequate. One could also say that the emptiness simultaneously transcends the changing forms. Consider, for instance, the spinning experiment with the experience of the still centre and the room moving through it. ‘Not two, not one’ as is said in Zen.

The Buddha warned us not to confuse his pointing finger with the moon. Words are useful pointers, but the essential point is to see reality just as it is, right now. While we need to distinguish between the experience and our concepts of it, we of course do not want to swing too far in the other direction and deny that words and concepts are useful at all. There is no phenomenology, in the sense of a rigorous method of describing and mapping out experience, without them.

8. A Distortion of Zen Phenomenology?

Here I will consider some objections to my interpretation of Zen phenomenology. The first objection, I will consider is that the reference to ‘no eyes, no, ears and no nose’ in the Heart Sutra is based upon a mis-reading of this text. According to the standard interpretation of the Heart Sutra, Tung-Shan’s initial confusion about ‘no eyes, no ears, no nose’ in the Heart Sutra could have been easily cleared up. The Sutra is not denying the existence of eyes, ears and nose, but only that they have intrinsic natures. They are empty of independent self-existence like all phenomena (Garfield 2014, p. 65; Hanh 1998, p. 135; Hanh 2017). This classical Buddhist interpretation of emptiness can be traced back to Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka.28 In particular, things are empty because of their impermanence and interdependent co-arising. The doctrine of impermanence is that all things are continually changing. Tables, trees, clouds, and people are all different from moment to moment. They have no underlying unchanging essence. The doctrine of interdependent co-arising is that there are no separate phenomena. The bee and the flower are dependent upon each other. They further depend upon the soil, the rain, and sunshine, and these depend upon still further phenomena. Thich Naht Hanh explains emptiness in terms of ‘inter-being’ (Hanh 1998, p. 135). The notion of inter-being is a useful way of understanding emptiness, while avoiding the mistake of taking the doctrine of no-self to be eliminativism about the self, eyes, ears and so forth.

Whether or not Tung-Shan was simply confused about the Heart Sutra, his understanding of it was important to his subsequent awakening. Furthermore, in support of Teng-Shan, the Heart Sutra could also be interpreted as denying subject-object duality. Jay Garfield argues that the Yogācāra school shifted the meaning of the classical Buddhist view of emptiness from a statement about the non-independent existence of objects, to the denial of subject-object duality (Garfield 2014, p. 74). In other words, the shift is from a third-person or objective stance to a first-person or subjective stance. Read this way, the Heart Sutra can be thought of pointing to the phenomenological fact that no eyes, ears or nose get in the way of sights, sounds and smells. In fact, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (a Yogācāra text) was one of the most important texts in Chan.29 This later interpretation also has the advantage that it is not merely intellectual, but points to one’s immediate experience and so fits with Zen’s emphasis, at least in the living tradition, upon first-person experience, and in particular directly experiencing one’s own nature. It is no longer a mere insight into one’s ultimate emptiness, but a direct seeing of it.

Peter Hershock contends that Buddha Nature in Chan is not an unchanging substantial essence, or True Self but is merely a disposition to awaken (Hershock 2019, pp. 14–15). He argues on semantic grounds that:

Buddha-nature could be seen as a propensity for entering into enlightening forms of conduct and relationship, rather than as a substantial essence. Buddha-nature is not something hidden “in” each of us, but rather something that manifests as a distinctive pattern and quality of interactive conduct.(Hershock 2019, p. 15)

I have endeavoured to be neutral about “Zen metaphysics”. I take the phenomenology to be consistent with both a True Self account and an account in which one has no self-nature or essence at all. However, Hershock’s (2019) portrait of awakening is in tension with the current account, in that I have taken awakening to be a direct experience of one’s nature rather than a disposition to act. Of course, both the experiential and dispositional accounts may be true of Zen awakening. The dispositional account by itself, however, does not seem to account for the many references in the Chan literature to Buddha Nature being colourless, shapeless, still, and boundless, nor the isomorphism between the phenomenology explored here and descriptions of Buddha Nature.

Although we have explored a phenomenology consistent with Zen language, perhaps the many examples of apparent ‘headlessness’ in Zen—Original Face, chopping off one’s head, tonguelessness, as well as ‘seeing’ into one’s nature are merely metaphors (e.g., Sharf 1995, p. 249). For instance, chopping off one’s head could merely refer to the need to put an end to all discriminating thoughts. This possibility should certainly be conceded. Similarly, ‘Seeing’ into one’s true nature could merely refer to a form of direct or intuitive knowledge. However, given that prajna (intuitive wisdom) cannot be known except in the having of it, it is not entirely clear what it is. It does not seem, then, that a perceptual aspect such as investigated here can be ruled out in advance. In fact, as we have seen, much of Zen apparently involves directly pointing to perceptual experiences.

That there are so many references to facelessness in Zen is odd, but perhaps not too troubling for those that hold that these are merely metaphors. However, when this is combined with the fact that attending is this direction (taking a backward step), reveals a colourless, changeless, unbounded emptiness (exactly as described in Zen)—the coincidence is almost miraculous.

From a modern perspective, the strongest reason in support of the current interpretation is that the essence of Zen is direct experience. In Zen, experience always comes before doctrine, including (especially) Buddhist doctrine. Since the experiments show how to directly experience emptiness by attending inwards, it seems reasonable that these are the very same experiences described by the original Zen practitioners. The strength of the reconstructive phenomenological approach, in particular, is that it works in both directions, from text to phenomenology and from phenomenology to the text. The phenomenology and the text are hence mutually supporting. A merely intellectual understanding of the texts of Zen, on the other hand, is not true Zen, just as the scholarship of recipes is not true cooking.

However, the assumption that the essence of Chan is direct experience has been strongly challenged by historiographical analyses. What is predominately known as Buddhism in the West is the result of recent reform movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries which scholars refer to as ‘Buddhist Modernism’.30 In response to cultural exchange and threats such as colonialism and modernisation, a new Buddhism emerged that was a hybrid of Asian and Western thought. In particular it portrays Buddhism as rational, scientific and experience-based, while de-emphasizing Buddhism’s rituals and supernatural doctrines. Robert Sharf (1995) points out that the contemporary focus on direct religious experience in Zen was in large part due to the influence of a small number of Japanese intellectuals, such as D. T. Suzuki and Nishida Kitarō who themselves were strongly influenced by their encounter with Western thought. This new form of Zen was exported to the West, where it underwent further development. This transformation in how Zen was interpreted and practiced in the 20th century is difficult to deny. Sharf also points out that the phenomenological notion of ‘experience’ was in fact rarely used in Chan (Sharf 1993, p. 22). This being said, it may have been that talking and writing about personal experience was itself strongly discouraged in the Chan tradition.

One of the motivations behind the historiographical approach is that the best evidence we have for understanding ancient cultures are their external expressions such as ritual, performances and texts. These are indeed important sources of evidence, but not the only source. We also have the indirect evidence of contemporary practitioners. By reducing religious traditions to their outward appearances, in the form of ritual, performance and texts, the implication seems to be that the inside story of these practitioners was irrelevant to their practice. In this regard, historiographical analyses resemble the methods of behaviorism. Were the Chan masters really just ritualistic robots with little interest in their first-person experience? Or were they radical empiricists that disdained ritual, as portrayed by D. T Suzuki and other Buddhist modernists? The truth perhaps lies somewhere in between these two extremes.

The point that we cannot just assume from the textual evidence that direct experience had a primary place in Chinese Zen is well taken. Here, comparative phenomenology can offer an alternative means of supporting the importance of meditative experience. If the texts left behind were descriptive (or perhaps prescriptive) of religious experiences, then a strong parallel would be expected between the texts and contemporary contemplative experiences. By showing that there is such a parallel, one does not need to merely assume that original texts are describing/prescribing experiences, rather the isomorphism itself provides prima facie support for this hypothesis.

Sharf combats this type of reasoning by arguing that in modern contemplative contexts, there is very little agreement as to what counts as a genuine experience of awakening, nor the best methods for achieving this. In particular, there has been a failure to identify clearly delineated experiences which map onto Buddhist terms such as Samatha, Vipassanā and Satori (Sharf 1995, pp. 261–65). This may well be the case, however, the awareness exercises presented here, by contrast, offer remarkably consistent phenomenological outcomes. Indeed, what phenomenal difference could there be between experiences of ‘nothingness’? (Harding 2001, p. 30).31

Even if it turned out that no Zen masters ever recognised their first-person facelessness, one could argue that as this is direct lived experience, it is just what we mean by Zen in the contemporary context. In this sense of the term, ‘Zen’ is not a purely religious or cultural phenomena, but a reference to a way of being that cuts across times and cultures. This is one reason why Zen is used apart from Zen Buddhism in the modern context (Grigg [1994] 2012, pp. 173–79). In this sense, the intriguing parallels between Chan and the Headless Way are of intrinsic interest, even if this understanding of Zen is merely a modern invention. Of course, from the perspective of contemporary practitioners, awakening itself and its possible practical benefits is the central point of interest, rather than these dry scholarly disputes.

9. Merely an Illusion?

When Neo exited the Matrix and arrived in the real world, his first question should have been, ‘How do I know that this is the real world? How do I know that this is not also a simulation?’ Analogously, the ‘headless’ experience cannot be called a form of genuine awakening if the experience itself is an illusion. How do I know that this is my true nature? It will not do to merely assume that these experiences are valid. Are these experiences merely perceptual illusions? Is it just the case that the eyes cannot see themselves? These are important questions.

Is my true nature really colourless, changeless and boundless? Perhaps it merely seems that way. In living Zen traditions, experience is reality. Phenomenology is metaphysics. The answer to this question, then, if we take a Zen approach is a resounding yes. If this seems to be emptiness, then it is emptiness.32 If this seems like stillness, then it is stillness. While this provides a response to questions about the veridicality of the experience, it does not follow necessarily from this that this emptiness is my essential nature.

Perhaps the experience of an absence here is just because the eyes cannot see themselves. In responding to this objection, we should first distinguish between two senses of ‘see’. In the third-person sense of ‘see’, seeing is a causal process—light reflecting from an object to an eye, to stimulation of the visual cortex. Light striking the retina is not sufficient for seeing to occur (eyes as such do not actually ‘see’). ‘Seeing’ only really occurs at the end of the causal chain (in the brain? by the brain?). However, the scientist does not find a conscious visual experience (i.e., conscious seeing) anywhere in this causal chain. It could all just go on unconsciously (Harding 1982, p. 30). My visual experience depends upon these processes, but it is not anything like them. The light waves, and chemical and neural processes are totally colourless as far as science is concerned. First-person seeing by contrast is about the conscious experience itself.

What is it that actually sees from your first-person experience? Hui-Hai asked: ‘Do eyes and ears perceive? No. Only your own Buddha Nature, being essentially pure and utterly still, is capable of this perception’.33 This statement of Hui-Hai suggests an argument in favour of this ‘emptiness’ being my essential nature. To consciously see the world, I need to be compatible with taking on its qualities. Things tend to exclude each other, whereas ‘emptiness’ has no qualities which could exclude things. As an analogy, if a film screen was coloured red, all blues projected on it would appear purple. To take on colours, then it seems that you need to be transparent, to take on sounds you need to be silent, to take on feelings you need to be feelingless (Ramm 2017, pp. 146–47; Ramm 2019, p. 6; Shear 1998, pp. 676–77; Shear and Jevning 1999, p. 202).

A second reason for believing that this is your essential nature comes from science. Suppose we take an entirely third-person approach to what I am. Does not this approach conflict with the first-person experience? From my perspective, I am looking out of nothing right where I am at zero distance. When I look at my hand, that is how I appear to myself at say 30 cm. For another observer my hand looks similar at the same distance. In a full-sized mirror from a few feet away, I appear as a quite ordinary human. I also appear as an ordinary human to another observer at the distance of a few feet. Thus far, the findings are consistent.

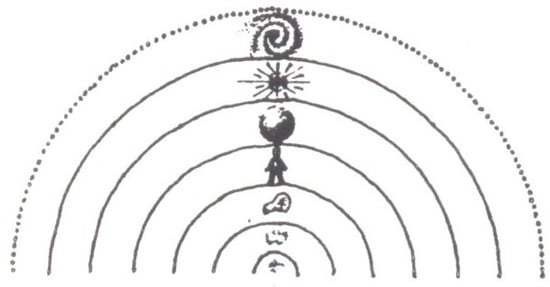

However, is it true that I am a non-thing right where I am? To test this the scientist needs to approach me and carefully observe what happens. First, I will appear as an entire human, then as a head, then an eye. Closer still, if they use a microscope, I will appear as cells and even closer as molecules. With further scientific and theoretical apparatus, I appear (in a broad sense of ‘appear’) as atoms which are mostly empty space. Closer still, my thinghood dissolves altogether into ghostly particles. These are more like unbounded ripples in a universal-wide field than things. For other observers, I am concentric layers of appearance, which are less and less thing-like at closer distances, until I am virtually nothing at centre. It seems then, that my central fundamental nature (what I am in myself), is non-thing-like. Receding from me, I appear as a human, a city, a continent, a planet, a star, a galaxy (see Figure 1). In Harding’s view, I need all of my layers to function. I cannot reflect the world without the incoming stream of influences cascading through my layers to my central reality. If any of the long train of events by which I see the object is disrupted, then so is my experience of it (Harding [1998] 2011).

Figure 1.

My Appearance for Others from Different Distances: Galaxy, Star, Planet, Human, Cells, Molecules, Atoms, etc. (Harding 2001, p. 31). Reproduced with Permission from the Shollond Trust.

Hence that my central, essential nature is empty, far from being undermined by the third-person scientific perspective is in fact confirmed by it. The third-person view of me fits my first-person experience, because for myself, at zero distance, I also seem to be an empty non-thing. However, we must add that I am not merely empty where I am, but full of the world. Rather than conflicting with each other, first-person science and third-person science arguably complement and complete each other (Harding 2001, pp. 7–8).

10. Analysing an Awakening Experience

I showed how Douglas Harding’s first-person experiments can potentially illuminate Zen accounts of awakening and vice versa. This experience can also be investigated in its own right independently of any religious tradition. Given that the experience involves seeing that (1) I am empty or void and (2) I am totally unified with the given scene, it clearly fits within the category of ‘awakening experience’ as I have used the term. Certainly, many will not agree that the experiments uncover one’s essential nature and hence that the experience is a genuine form of awakening. For the purposes of discussion, however, we can just focus on the phenomenology itself.

The key to the current awakening experience is attention. It is turning your attention 180 degrees from the objects before you, to who or what seems to be seeing them. It is not just attending to where I find a vast emptiness, but also attending outwards at its filling and seeing how they are one. Douglas Harding refers to this practice as two-way attention (Harding [1986] 2000, pp. 54–55). It is a form of diffuse attention, in contrast to our usual outward object-focused attention.

It should be emphasized that this is not a peak or mystical experience (though it could precipitate such an experience for some), but rather a simple, perceptual-like experience that I am nothing for myself where I am looking from. We can then distinguish two types of awakening experiences: (1) Mystical/peak experiences, and (2) Valley experiences (Harding [1986] 2000, p. 46). Mystical experiences, as documented by Evelyn Underhill ([1911] 1961) and F. C. Happold ([1963] 1981) are rare, ecstatic experiences which commonly involve feeling a union with God or the cosmos. They are associated with extended religious practice and also the ingestion of psychedelic drugs (Richards 2015). A valley awakening experience, however, is plain, simple and ordinary. This experience is also voluntary and repeatable in that it is precipitated by a shift in one’s attentional focus while mystical experiences are usually unbidden and unrepeatable.

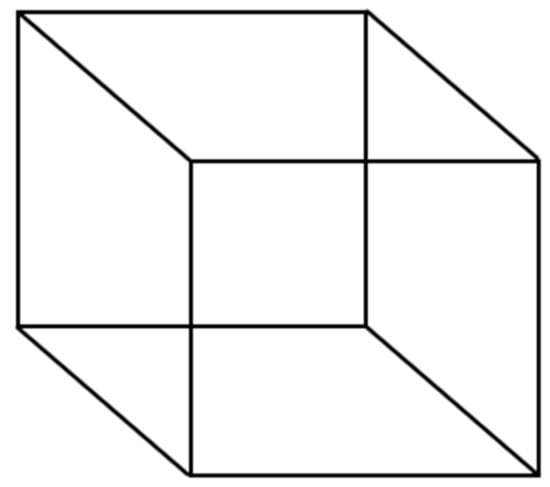

One response to the experiments is ‘I don’t get it’. As a perceptual-like experience there is nothing to understand. It is as basic and unexplainable as seeing the blue expanse of the sky. It should be emphasised, though, that attending to what you are apparently looking out of is a form of meditation and hence may not transform one’s experience immediately. It needs to be practiced. In my experience, this results in a transformation of one’s perceptual experience. It can be likened to a Gestalt shift. An example of a Gestalt shift is the Necker Cube (Figure 2 below). In this perceptual illusion, which square is perceived as its front side, switches depending upon where one attends.

Figure 2.

The Necker Cube.

In the ‘headless’ experience, rather than looking out a head, the experience shifts to me seeming to be looking out of an unbounded open space. Rather than being a thing moving about in the world, the world is in me. I am motionless and the landscape and objects move in my consciousness. I still feel my head and bodily sensations, but I am not confined by them, rather these are also in my consciousness. My thoughts and emotions are not in a head-box, but in the same field as the scene. Things are seen much as before, but attention is broadened to include the field of consciousness itself.

Other experiential shifts are also distinguishable. Attending inwards, the distinction between the gap and the scene is emphasized. However, rather than just nothing, this unbounded opening seems to be awake to itself and the world. It could be described as a luminous emptiness (pure awareness) that is nevertheless full of the scene.34 In Chan, pure awareness is called ‘chih’. Shen-Hui stated that ‘the one word “chih” is the gateway to all mysteries’.35 The Chan master and historian Tsung-mi was prominent in interpreting Shen-Hui’s use of ‘chih’ as denoting ‘awareness’ and holding that recognising one’s true nature as ‘ever-present Awareness’ and ‘empty tranquil Awareness’ is the essence of awakening (Gregory 1985).

In another experiential mode, when attending both inwards and outwards simultaneously (two-way attention), the total unity between the ‘space’ and the scene is emphasised, such that I seem to be that very scene. It could be expected that the more outwards focused this diffused attention, the more that one will be absorbed into the scene. Analogous, to the Necker Cube these are different modes of an indivisible unity. The Necker Cube remains a single unified figure throughout the switching between its aspects. This analysis suggests at least three possible modes of consciousness: (1) Ordinary everyday consciousness of being a thing in the world, (2) Being an aware-no-thing full of the given world, (3) Being the given world.

Like the Necker cube, which mode is experienced depends upon one’s attentional orientation. Additionally, none of these experiences are separable. The world is there, just as before. Here then is a way of understanding the Buddhist doctrine that delusion and awakening are identical (yet somehow different). Awakening is not like waking from a dream, but rather a change in one’s perspective. One’s true nature was implicitly present the entire time under one’s very nose (or more precisely behind one’s nose blurs). This reminds one of Wittgenstein’s famous statement ‘The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice something–because it is always before one’s eyes.)’ (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 50).

If the experience is so simple and obvious why don’t more people spontaneously have it? Assuming that this is a genuine awakening, what are the sources of the delusion? Douglas Harding identifies at least four reasons why we do not normally notice our first-person perspective.

The first reason is cognitive. We suffer from false beliefs. Douglas Harding provides a novel definition of the delusion from which we ordinarily suffer—‘I am here for myself what I look like to others over there’ (Harding 1996, p. 29). We are taught since early childhood to identify with how we look like to others such as in photographs and how we look to ourselves in the mirror from a few feet away. This is a category error because it confuses what I am at zero distance for myself with how I appear from a distance.

The second reason is imagination. The closed eye experiment showed that bodily sensations are less detailed and more dynamic than I usually notice, not to mention shapeless. It seems then that I learn to map how I look to others onto these sensations and so thing myself. I hallucinate a head here blocking up the centre of my phenomenal world. This visual imagery combined with tactile imagery (how I feel to myself and others through touch), give the sense that my phenomenal body is presented as a static, all-at-once shaped object. This creates the illusion that I am separate from the perceived world (in a body), rather than at large as the scene (which includes my thoughts, feelings, body and the world).

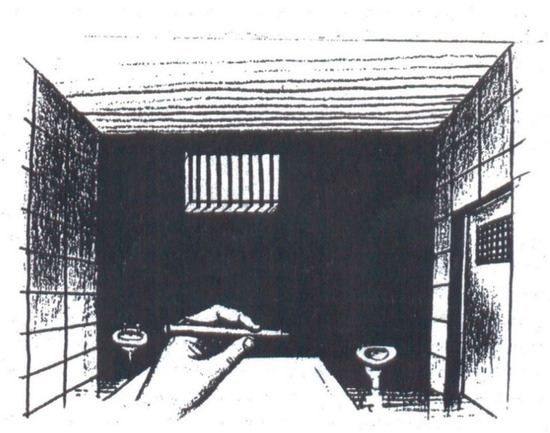

Thirdly, we have an attentional bias to only attend outwards, never inwards at the looker. The result is that we overlook half of the view. As an example, we rarely notice that phenomenologically speaking an entire wall is missing whenever we are ‘in’ a room. We fill in four closed walls in imagination, and so this vast unbounded Gap goes totally unnoticed. Harding makes the point that even a jail cell cannot confine me, because for myself it is in my awareness (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A First-Person Sketch of Being “in” a Jail Cell With its Missing Back Wall (Harding [1992] 2002, p. 17). Reproduced with Permission from the Shollond Trust.

Fourthly, language systematically covers up my first-person experience by describing everyday situations from the third-person perspective (Harding [1990] 1999, pp. 65–66; Harding 2001, pp. 33–37). A prominent example is that we meet face-to-face. Phenomenologically speaking, I can only see others faces because my face is totally absent. The lived experience is that we are face-to-no-face (Harding [1986] 2000, p. 58). I am replaced by others. Another example, as discussed above is the confusion between the first-person and third-person senses of ‘see’. The third-person sense is a causal-functional process involving things, eyes and brains, while the first-person sense is the phenomenal experience of seeing which is phenomenally eyeless. A final example is the way we talk about thoughts and images as being ‘in the head’ as if there was a box here that kept them separate from the perceived world. I say that ‘the song is stuck in my head’, whereas it would be more phenomenologically accurate to say that ‘the song is stuck in my world’.

11. Conclusions

Comparative phenomenology can move in two directions: (1) applying religious texts to analysing phenomenal experience and (2) using phenomenal experience to assist in interpreting religious texts. Although moving in the second direction is controversial in the case of Buddhism, I hope to at least have shown that Zen is useful for understanding first-person experience, and that first-person experiments are fruitful, perhaps even transformative, phenomenological methods.

Sometimes Buddhist meditative practices are characterised as a first-person science of the mind (Harris 2014, p. 209). Certainly, an empirical attitude is needed and these methods provide valuable insights about the mind. Yet they lack the exactness and reliability of scientific methods. In Zen, Kensho is a great breakthrough in one’s practice. It may happen a few times in one’s lifetime or perhaps not at all. The experiments, on the other hand, are arguably unique amongst methods of self-inquiry in their precision and directness. Clear cut instructions are given for how to turn attention within and see one’s original nature. In particular, apparatus is used to direct one’s attention and contrast how you appear to others with what its actually like to be you.

Thompson (2020) holds that awakening in Buddhism cannot be the subject of scientific study for a number of reasons: (1) It cannot be understood outside of its religious framework. Claims about awakening are understood and validated within that that pre-established religious framework (ibid., p. 36). (2) There is also a lack of agreement within Buddhism about what awakening consists in, for example, is it a conceptual or non-conceptual state? (ibid., p. 147). Is it necessarily linked with compassion? (p. 162). These issues are the subject of religious and philosophical debate, not scientific questions.

By contrast, the methodology of the experiments can presumably be carried out and the results obtained by a conscious observer of any culture at any time, whether religious or not. The basic experience can also be understood without a religious framework: 36 For example, judging that I am pointing at a seemingly colourless, shapeless, unbounded opening. Of course, some assumptions are needed such as an understanding that the experiments test how things seem to you, rather than how you believe things are. I also argued that this form of ‘awakening’ is predominantly perceptual-like in nature. Hence, this experience is clearly enough defined to be empirically studied.

Whilst, the basic experience is perceptual-like, working out of the meaning of the experience in one’s life is the work of a life-time and here philosophical and religious concepts from varying traditions are useful. There is an unending interplay between meaning and experience. Additionally, as we saw above, Zen insights about nonduality were useful for understanding the experience and vice versa.

Questions remain about whether or not the experience itself is partly conceptual or totally nonconceptual, however, this problem applies to perceptual experience in general (Bermúdez and Cahen 2020). Lastly, you do not need to be compassionate or ethically good to see what you are for yourself. However, being consciously open for others (disappearing in their favour), at least in theory, provides a basis for unconditional love. Whether this is the case in practice is an empirical question. From anecdotal reports, the experiments are a reliable means of transforming one’s first-person experience, in particular in producing experiences that are consistent with contemplative traditions’ descriptions of the emptiness of the self and subject-object nonduality (Lang [2003] 2012). The repeatability and apparent reliability of these methods, hence opens up a class of awakening experience to empirical investigation, and as I have tried to show, can provide new insights into nondual traditions. However, the most important question for investigation, by far, because it is the most personal, concerns the nature of oneself: What is aware of these black marks on a white background right now?

Funding

This research was funded by the Shollond Trust (reg. charity no. 1059551).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Robert Penny, Terje Sparby and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. My thanks also to Ross Bolleter and Peter Bruza for insightful discussions on Zen.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Albahari, Miri. 2002. Against no-ātman theories of anattā. Asian Philosophy 12: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahari, Miri. 2009. Witness-Consciousness: Its Definition, Appearance and Reality. Journal of Consciousness Studies 16: 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, José, and Arnon Cahen. 2020. Nonconceptual Mental Content. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2020 ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/content-nonconceptual/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Blofeld, John. 1958. The Zen Teaching of Huang-Po: On the Transmission of Mind. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blofeld, J. 2007. Zen Teachings of Instantaneous Awakening (Ch’an Master Hui Hai). Totnes: Buddhist Publishing Group. First published 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, David J. 2005. The matrix as metaphysics. In Philosophers Explore the Matrix. Edited by Christopher Grau. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Chen-chi. 1957. The Nature of Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism. Philosophy East and West 6: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, Thomas, and Jonathan Christopher Cleary. 2005. The Blue Cliff Record. Boston: Shambhala Publications. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Richard. 2006. Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Francis H. 1983. Enlightenment in Dogen’s Zen. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 6: 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Daoyuan. 2016. Records of the Transmission of the Lamp. Translated by S. Randolph Whitfield. Norderstedt: BOD—Books on Demand, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, Daniel C. 1991. Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, Daniel C. 2018. The fantasy of first-person science. In The Map and the Territory. Edited by Francisco Antonio Doria and Shyam Wuppuluri. Cham: Springer, pp. 455–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dogen. 2010. The Heart of Dogen’s Shobogenzo. Translated by Norman Waddell, and Masao Abe. Albany: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Domyo. 2019. Unethical Buddhist Teachers: Were They Ever Really Enlightened? March 1. Available online: https://zenstudiespodcast.com/unethical-buddhist-teachers/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. 2005. Vol. 1: India and China. In Zen Buddhism: A History. Translated by W. Heisig James, and Paul Knitter. Bloomington: World Wisdom, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fasching, Wolfgang. 2008. Consciousness, self-consciousness, and meditation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 7: 463–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasching, Wolfgang. 2011. I Am the Nature of Seeing: Phenomenological Reflections on the Indian Notion of Witness-Consciousness. In Self, No Self? Perspectives from Analytical, Phenomenological, and Indian Traditions. Edited by Mark Siderits, Evan Thompson and Dan Zahavi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, Sascha Benjamin. 2020. Look who’s talking! Varieties of ego-dissolution without paradox. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences 1: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, Robert K. C. 1999. Mysticism, Mind, Consciousness. Albany: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Jay L. 2014. Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Peter N. 1985. Tsung-mi and the Single Word ”Awareness” (chih). Philosophy East and West 35: 249–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grigg, Ray. 2012. The Tao of Zen. Rutland: Tuttle Publishing. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Bina. 1998. The Disinterested Witness: A Fragment of the Advaita Vedanta Phenomenology. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh, Thich Nhat. 1998. The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy and Liberation. New York: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hanh, Thich Nhat. 2017. The Other Shore: A New Translation of the Heart Sutra with Commentaries. Berkeley: Parallax Press. [Google Scholar]

- Happold, Frank C. 1981. Mysticism: A Study and an Anthology. Middlesex: Penguin Books. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 1982. On Having No Head (excerpts). In The Mind’s I. Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul. Edited by Douglas R. Hofstadter and Daniel C. Dennett. Middlesex: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 1996. Look for Yourself: The Science and Art of Self-Realisation. London: Head Exchange Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 1999. Head off Stress. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2011. The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth: A New Diagram of Man in the Universe, Digital ed. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2000. Face to No-Face: Rediscovering Our Original Nature. Carlsbad: InnerDirections Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2000. On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2001. The Little Book of Life and Death. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2001. The Science of the 1st-Person: It’s Principles, Practice and Potential. London: The Shollond Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Douglas Edison. 2002. The Trial of the Man Who Said He Was God. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Sam. 2014. Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality without Religion. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Hershock, Peter. 2019. Chan Buddhism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/buddhism-chan/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Irvine, Elizabeth. 2012. Old Problems with New Measures in the Science of Consciousness. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 63: 627–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipovic, Zoran, and Vladimir Miskovic. 2020. Nondual awareness and minimal phenomenal experience. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapleau, Philip. 2000. The Three Pillars of Zen. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Richard. 2012. Seeing Who You Really Are: A Modern Guide to Your True Identity, revised ed. London: The Shollond Trust. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leighton, Taigen Dan. 2000. Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Letheby, Chris, and Philip Gerrans. 2017. Self unbound: Ego dissolution in psychedelic experience. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2017: nix016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, David L. 2008. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, John R. 2003. Seeing through Zen: Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzinger, Thomas. 2020. Minimal phenomenal experience: Meditation, tonic alertness, and the phenomenology of “pure” consciousness. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences 1: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A. F., and Mou-lam Wong. 1990. The Diamond Sutra & the Sutra of Hui-Neng. Boston: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ramm, Brentyn J. 2016. Dimensions of reliability in phenomenal judgment. Journal of Consciousness Studies 23: 101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ramm, Brentyn J. 2017. Self-Experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies 24: 142–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ramm, Brentyn J. 2018. First-Person Experiments: A Characterisation and Defence. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 9: 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramm, Brentyn J. 2019. Pure Awareness Experience. Inquiry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, William A. 2015. Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Samy, Ama. 2012. Zen: The Great Way has No Gates. Dindigul: Vaigarai Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schwitzgebel, Eric. 2011. Perplexities of Consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharf, Robert H. 1993. The Zen of Japanese Nationalism. History of Religions 33: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharf, Robert. 1995. Buddhist modernism and the rhetoric of meditative experience. Numen 42: 228–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, Jonathan. 1998. Experiential clarification of the problem of self. Journal of Consciousness Studies 5: 673–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shear, Jonathan. 2014. The Inner Dimension: Philosophy and the Experience of Consciousness. London: Harmonia Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shear, Jonathan, and Ron Jevning. 1999. Pure consciousness: Scientific exploration of meditation techniques. Journal of Consciousness Studies 6: 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Hu. 1953. Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism in China its history and method. Philosophy East and West 3: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparby, Terje. 2015. Investigating the depths of consciousness through meditation. Mind and Matter 13: 213–40. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. 1953. Zen: A Reply to Hu Shih. Philosophy East and West 3: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. 1956. Zen Buddhism: Selected Writings of D. T. Suzuki. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. 1969. The Zen Doctrine of No Mind. London: Rider & Company. First published 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. 1974. Manual of Zen Buddhism. London: Rider and Company. First published 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. 1981. An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. New York: Grove Press, Inc. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Evan. 2015. Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Evan. 2020. Why I Am Not a Buddhist. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tung-Shan. 1986. The Record of Tung-Shan. Translated by F. William. Powell: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, Evelyn. 1961. Mysticism. New York: E. P. Dutton. First published 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria, Brian Daizen. 1997. Zen at War. New York: Weatherhill. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhoff, Jan. 2009. Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wick, Gerry Shishin. 2005. The Book of Equanimity: Illuminating Classic Zen Koans. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Windt, Jennifer M. 2015. Just in time—Dreamless Sleep experience as pure subjective temporality. In Open MIND. Edited by Thomas K. Metzinger and Jennifer M. Windt. Frankfurt am Main: MIND Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1922. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, International Library of Psychology, Philosophy and Scientific Method. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Dale S. 2000. Philosophical Meditations on Zen Buddhism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, Dan. 2003. Phenomenology and Metaphysics. In Metaphysics, Facticity, Interpretation: Contributions to Phenomenology. Edited by Dan Zahavi, Sara Heinämaa and Hans Ruin. Dordrecht and Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | David Chalmers (2005), argues that Neo is not massively deluded after all because the simulation can be considered the real world, while its fundamental reality is computational. This is analogous to tables and chairs still existing for us even though their fundamental quantum reality is radically different. This ‘two levels of reality’ approach is similar to the two levels of truths of Buddhism, i.e., relative and absolute. |

| 2 | Japanese Zen is another matter entirely, especially with Dogen who dispensed with Kensho altogether (Cook 1983). For Dogen, practice and enlightenment are one from the very beginning. One practices to actualise their intrinsic Buddhahood. For an apparent exception to his rejection of Kensho, see Dogen’s Fukanzazengi quoted below. |

| 3 | Both Buddhism and the Advaita Vedanta agree that there are no personal souls. The most common interpretation of Buddhism is that the Buddha also rejected the Upanishadic notion of the Self, such that neither is there a fundamental nature that is common to all beings (Pure Consciousness). For an argument against the view that the Buddha rejected the Upanishadic tradition see Albahari (2002). |

| 4 | As they are not relevant to the current arguments, I set aside the Buddhist belief in the Buddha’s achievement of Nirvana which is associated with a permanent eradication of the grasping self, moral perfection and even supernatural abilities such as omniscience and seeing past lives. |

| 5 | The term ‘enlightened’ was first used by Max Müller to describe the Buddha in 1857. It has since become the standard translation of bodhi (literally ‘awakening’). Richard Cohen (2006) points out that ‘enlightened’ is an infelicitous translation because bodhi is more process-oriented, whereas ‘enlightened’ is event-oriented. Enlightenment also suggests an illumination from the outside, a metaphor that is common in the Christian tradition where we can be illuminated/enlightened by God or the holy spirit. Awakening, by contrast is a personal transformation or realisation of one’s true nature from within. |

| 6 | On the two aspects of Kensho, Ama Samy states: ‘Awakening is first and foremost the realization of the core of one’s heart-mind as the unknowing, inexpressible mystery; this is awakening to Emptiness. Awakening is awakening to Emptiness—it is Emptiness awakening to Emptiness, so to say: it is the mystery of No-Self that is nowhere and everywhere. Secondly, it is the realization of this heart-mind as boundless openness to the world: It is the realization of the self as the world and the world as the self.’ (‘Koan, Hua-t’ou, and Kensho’ in Samy 2012). The experience of ‘ego dissolution’ is also commonly reported with the ingestion of psychedelics (Letheby and Gerrans 2017). Sascha Fink (2020) argues that such states might be better conceptualised as ‘ego expansion’ such as, ‘I am everything’, rather than paradoxical states such as, ‘I experienced a dissolution of myself’. |

| 7 | Thank you to Richard Lang for suggesting this way of thinking about the headless experience. |

| 8 | For further parallels between Headlessness and Zen, see (Harding [1986] 2000). |

| 9 | A vexed question in the literature is whether phenomenology should be (or indeed can be) metaphysically neutral (for a discussion see Zahavi 2003). I do not delve into this topic here. |

| 10 | The current first-person approach has some similarities with Terje Sparby’s ‘contemplative phenomenology’ in that it draws upon traditional sources, but where the focus is the description of experience itself and so is independent of any such traditional frameworks (Sparby 2015, p. 215). |

| 11 | |