Abstract

When the City of the Name of God of Macao marked 400 years of Portuguese administration in 1956, the Catholic community’s participation was marked by a wide range of activities that included liturgical celebrations, public processions and other devotions that involved large numbers of the lay faithful, members of confraternities, in addition to the clergy and religious of the enclave. Twenty-one years later the Diocese of Macao celebrated its own quatercentenary with celebrations of a decidedly more sober character and at the retrocession of Macao to Chinese control in December 1999, other than a few liturgical events and hierarchical presence at civic ceremonies, the Church was all but invisible. As the Diocese of Macao plans for its 450th anniversary, some of the former richness has begun to return. This paper outlines the long ebb tide and now-nascent flow of the tide of Catholic public piety in Macao over this period by reference to the Catholic religious processions of the City and seeks to offer tentative explanations grounded in the theological, ecclesial, political and cultural winds that have blown across the Pearl River Delta since the end of the Second World War.

Keywords:

Macao; processions; Catholic Church; Vatican II; public piety; Portugal; China; confrarias 1. Introduction

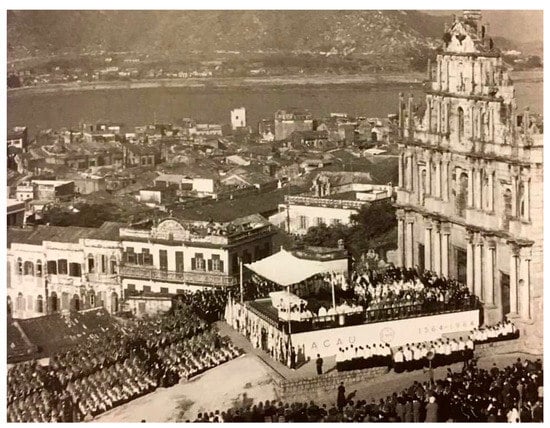

Apart from the earliest centuries of Portuguese settlement, when the Chinese population was itself very small, Catholics have only ever comprised a small minority of the population of the peninsula,1 public expressions of Catholic religious piety have been a constant feature of life in Macao, from its settlement by the Portuguese in the middle of the sixteenth century until the present day. The material expressions of this are unavoidable-in the Churches (the most striking of which is the ruined façade of the Church of the Mother of God, known colloquially as the Ruins of St Paul’s), the very few religious statues and the frequently encountered azulejo, the glazed tiles, depicting religious as well as historical themes. The most striking expressions of Catholic public piety in the city are, however, the frequent religious processions throughout the year. Once even more frequent than today, these processions survived into the mid-twentieth century, despite several changes in Portuguese constitutional settlements, many of which were more or less openly hostile to the Catholic Church. The quatercentenary of Portuguese arrival in 1557 was marked by processions led by the many lay confraternities (known by the Portuguese term confrarias, the term used throughout this article when referring to them)2 and still other expressions of Catholic public piety which displayed the ecclesial self-confidence that marked the dying days of Tridentine cultural Catholicism. Even during the Second Vatican Council, the public Mass before the Ruins of St Paul’s in June 1964, to mark four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the Jesuits (who, in fact, had actually arrived there in August 1562, (Anon 2012, p. 6)) showed little reduction in pre-conciliar triumphalist ceremony (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mass to celebrate the 400th Anniversary of the Jesuits in Macao before the Ruins of St Paul’s Church, 1964 (image courtesy of the Library of the University of Saint Joseph, Macao).

Over the following thirty-five years, until the return of the enclave to Chinese control on 20 December 1999, the number and scale of these public expressions of Catholicism reduced markedly. Recent years have seen something of both the beginnings of a resurgence of these processions and a change in the ethnic compositions of their participants, with Chinese now outnumbering Portuguese and Macanese, such that, at the time of writing, processions that had dwindled in size and importance have begun to grow, some processions that had fallen into desuetude have been revived and yet still others have been established.

This paper will consider the changes in the processions as an expression of Catholic public piety in Macao in the period from 1948 until the retrocession to Chinese control in 1999. It will note both the pattern of a discernable ebb in the number and scale of these processions across this period and offer a possible conjecture for the reasons behind it, before looking at the recent turn of the tide, its characteristics and the several possible impetuses. The tentative nature of any conclusions is not due entirely to the difficulty of establishing causation with any degree of certainty when considering trends in recent ecclesial history. Proximity to the events and the personal attachment of writers to particular theological, ecclesial and political positions mean that proper scholarly detachment is more difficult than might be the case when taking a longer view. In the case of the religious history of Macao, however, there are other challenges.

It is a truism, by no means unique to Macao, that the further back one goes, the scarcer the historical sources are, but there are particular circumstances in the history of the territory that create particular difficulties. The uncertainty of the 1941–1945 position of Macao as a territory of a non-combatant in the War, yet surrounded by the Imperial Japanese forces who had been so brutal in their treatment of Catholic religious orders in Hong Kong, was sufficiently uncertain to encourage what appears to be a certain economy in ecclesiastical record-keeping, despite the sterling efforts of Fr Manuel Teixeira, editor of O Boletim Ecclesiástico da Diocese de Macau, from 1934 until 1948, to ensure important events were recorded.3 Later, the 12-3 Riots of December 1966, an outworking of the Cultural Revolution in Mainland China, led to the destruction of perhaps one third of the official records in Macao (Hao 2011, p. 6). There is also an intriguing lacuna in the archives of the Diocese of Macao for much of the century prior to those riots. There is some evidence that they were deliberately shipped to Portugal to avoid difficulties in the event of forced return to Chinese control (Fernandes 2006, p. 48), although their current whereabouts are unknown. Finally and it is by no means certain that this too was not a conscious attempt to make access to potentially damaging of compromising material more difficult, should those hostile to the Catholic Church wish to gain access-until very recently, no serious attempt had been made to catalogue properly and store securely such archival material that does exist. This work is currently being undertaken but led to the closure of the archives to researchers in 2018. They are not expected to be accessible until 2023, at the earliest.

These factors have created a situation where often the only available sources are either those of a skeletal nature in the Macao Government’s O Boletim do Governo de Macao, the historical articles of Fr Teixeira in the Boletim Ecclesiástico, which-like his work in the sixteen volumes of Macau e a sua Diocese-often lack adequate references to primary material, unsourced journalism (both ecclesiastical and secular), and accounts of oral history, which are often third-hand recollections or worse.4 The historiographical challenges this presents are not quite insurmountable but necessitate a degree of extreme circumspection, particularly in ascribing direct causality to specific changes, and rather more use of ethnographic (and even autoethnographic) techniques than is either usual or, at least to the present author, comfortable. Despite the limitations these factors place on the present task, it is not impossible to discern a pattern in the changes in Catholic public piety in Macao over the period under consideration and to map them against events and trends both secular and ecclesiastical. This article is, as far as the author can establish, the first scholarly attempt so to do.

2. Historical Background

Located on the southern shore of the main channel of the Pearl River, where it disgorges into the South China Sea, for most of its settled history Macao was little more than a collection of small fishing villages, gathered around the A-Ma Temple from which the Portuguese derived the name Macao.5 The Portuguese arrived in the Pearl River Delta region in 1513, with the voyage of Jorge Alvares (Hao 2011, p. 10), an episode in the early Portuguese attempts at extending their trading, political and religious influence across the globe. There is no evidence that they landed at Macao during that expedition nor in a voyage four years later that took them up the Pearl River Delta to the City of Guangzhou in an attempt to open up formal relations with the Ming Dynasty then ruling China (Wills 1998, pp. 336–37).

Obtaining temporary permission from the Chinese authorities to establish a settled trading post at Macao in 1557 (Wills 1998, p. 343), the Portuguese began the business of building churches almost immediately. By the date of the confirmation by Pope Gregory XIII, in the Bull Super specula militantis ecclesiae, of 23 January 1576, of the establishment of both city and diocese by King Sebastian under the padroado real system,6 much of the current physical religious landscape of Catholic Macao had begun to take shape.7 The padroado system consisted of an arrangement between the Holy See and the Kingdom of Portugal that sought to yoke together the religious and missionary interests of the Catholic Church with the politico-economic interests of the country. It gave to the King of Portugal certain privileges in or endorsements of efforts at trading and colonial expansion—although, at least in Portugal’s case the initial explorations did not have in view the control of large-scale territory and populations—in exchange for the promise of the establishment of Churches and the protection of missionary activity. It also provided protection from competition from other European (Catholic) nations-particularly Spain-engaged in similar expansion.

The system, which lasted formally until the retrocession of Macao to the People’s Republic of China in 1999, meant that it is, in many ways, impossible to separate the political and religious interests of the Portuguese expansion. This was especially so in the case of Macao, since the settlement here had little by way of resident Chinese until the mid-eighteenth century-overnight residence within the walls of Macao being forbidden by the Chinese Emperor and even daytime presence being regularly withdrawn, along with material supplies, by the Chinese authorities at times of strain in the relationships. Macao was, to all intents and purposes, for much of its early Portuguese history, the period when many of the religious processions were established, a Portuguese city with a Portuguese or European population. The processions might properly be seen as the religious identity of the city’s inhabitants, rather than expressions of the projection of power to impress and influence the Chinese. Indeed, apart from the training of missionaries for work in Mainland China, little attempt seems to have been made, until the latter-half of the twentieth century to evangelise local Chinese. The survival of the Taoist Na Thcha Temple stands as a physical witness to this singular reality. Once abutting its walls, the Temple has outlived the grand Church of the Mother of God that once dominated the centre of the city but of which only the façade remains.

The close identification of political and ecclesiastical authority in Macao survived the fall of the Portuguese monarchy and the establishment of the First Republic in 1910, a republic openly hostile to the Church in Portugal itself. Distance no doubt played a part the fact that this relationship endured when those between the Church and State in Portugal had loosened. Nevertheless, it is this enduring identification of Portuguese ecclesial and national interests which explains why, in many ways, when looking at the history of ecclesial life in Macao prior to 1999, it is always necessary to have political developments in Portugal in the forefront of one’s mind.

The phenomenon of religious procession is intimately connected with this close identification of church and state in the early modern period, and particularly within the Portuguese Empire. Given the fragile hold the Portuguese were always to have on the concession, even from the very beginning they held it very much on the sufferance of Qing Dynasty China (Isabel dos Guimarães Sá 2016, pp. 155–57), the capacity of religious processions to support claims to authority was considerable. The “physio-psychological impact on its spectators” (Drnovšek 2018, p. 218) of these processions was well understood by ecclesial authorities as well as civic/colonial leaders (although this may be largely a distinction without a difference under the padroado real), as the decree of the Council of Trent On the invocation, veneration, and relics of saints and on sacred images, of 1563, recognised (Denzinger 2012, pp. 429–30). There were antecedents for processions aplenty in late-medieval Catholicism (Mystery plays, guild processions, etc.) and, indeed, in the earliest Catholic practices (Egeria notes and takes part in already well-established processions in Jerusalem during her stay there in the late fourth century (McGowan and Bradshaw 2018), and the processional nature of the Roman liturgy is a signal feature of the ceremonies described in the seventh century Ordo Romanus Primus (Atchley 1905)). Nevertheless, the impetus given to the establishment of processions during the Catholic Reformation by the Council of Trent and those religious orders-the Jesuits and Capuchins-most associated with its advancement led to a particular flourishing at the end of the sixteenth century. Whilst in no way discounting the sincerity of the religious motivations of participants and organisers, these processions served to advance political claims.8 In Macao, as much as in Portugal (where a procession of striking similarity to Macao’s own Procissão do Nosso Senhor Bom Jesus dos Passos (“Bom Jesus”-see below) was established in 1587), during these processions the city became the “physical and symbolic stage of power of the Portuguese state” (Bicalho 2001). As Charlotte de Castelnau L’Estoile has noted, “As processions moved about the city, they took possession of the urban space, making the city itself a ‘physical stage’ for the projection of power.” (de Castelnau-L’Estoile 2016, p. 42). The eclipse of that power and the loosening and eventual dissolution of the bonds between Portuguese political power and the ecclesial life of the Catholic community in Macao has been reflected in the history of the various Catholic religious processions, especially in the half-century leading up to the resumption of Chinese rule is a subject deserving of greater attention.

The couplet in the title of this paper contains a description of the procession and pre-embarkation vigil of Vasco da Gama and his men before the voyage of 1497–99, which led to the discovery of the sea-route to India. It comes from the fourth canto of the great epic poem of the Portuguese language, Os Lusíadas, written by Luís Vaz de Camões. It has long been thought that Camões wrote the poem during his employment in Macao as a minor government official, almost immediately after the Portuguese arrival.9 Whether that is so or not, it seems clear that the image of the public piety of de Gama in Lisbon that Camões sought to evoke in the service of his poetry became a reality in the Portuguese enclave very early. For example, an English visitor to the territory, Peter Mundy, records the existence of the “plays and processions” of the Jesuits at St Paul’s in 1637 (Mundy 1919, III–i:162), and the Boletim Oficial de Macau, in June 1862, claimed that the procession of St John the Baptist had been held for two hundred and forty years without interruption (O Boletim Oficial de Macau 1862, p. 120).10

By the early nineteenth century, the accounts given by Harriett Low and her Swedish contemporary expatriate in Macao, Sir Anders Ljungstedt of, for example, the Procissão do Nosso Senhor Bom Jesus dos Passos (“Bom Jesus”), on the first Sunday of Lent, describe ceremonies that were clearly well established and which differ in no significant manner from the way in which they were carried out in 1972, as recorded in a Rádio Televisão Portuguesa film (Noticiário Nacional: Procissão Do Senhor Dos Passos Em Macau 1972),11 or in 2019 (see Figure 2) (Low Hillard 2002, pp. 107–8); (Ljungstedt 1836, p. 155).12 The procession follows a platform, upon which a statue of Jesus, falling under the weight of the Cross he carries (the Bom Jesus: the Good or Holy Jesus), is mounted, through the streets of the centre of Macao from the Cathedral to the Church of Santo Agostinho (there is a procession the previous evening in the opposite direction but neither Low nor Ljungstedt make mention of it-it may be a later development). The platform is carried by the members of the Confraria de Bom Jesus, wearing violet waist-length capes, and accompanied by a band playing mournful tunes. In both the 1972 film and photograph of the 2019 procession (Figure 2), behind the confraria and the figure of the Bom Jesus, the Bishop of Macao, under a canopy, accompanied by clergy and altar servers, walks carrying a relic of the True Cross. The procession stops a number of “stations” where the Bom Jesus is greeted by a young woman dressed in white and playing the part of Veronica (a non-biblical figure popular in Catholic devotions associated with the devotion of the Way of the Cross since at least the thirteenth century). She unveils an image of the face of Jesus, whilst singing a lament. In response to Veronica and at the other stations, prayers and meditations on the last journey of Jesus are said or sung. In 2021, with the pandemic restrictions still in place, a reduced ceremony took place in the Church and grounds of the eighteenth-century Seminário de São Jose.

Figure 2.

Procession of Bom Jesus, 10 March 2019 (image courtesy of Manuel V. Basílio).

By the beginning of the twentieth century there were at least twenty Catholic religious processions each year in Macao, including those of the Passion on the first Sunday of Lent, the Dead Christ on Good Friday, the Risen Christ on Easter morning, Our Lady of Pleasures also known as Our Lady of Remedies (in Portuguese A Nossa Senhora dos Prazedes or dos Remedios) at the end of April or beginning of May, Corpus Christi, the Guardian Angel of the Kingdom of Portugal on 10 June, St Anthony on 13 June, St John the Baptist on 23 June, St Roque on the Second Sunday of July, the Assumption on 15 August, the Immaculate Conception on 8 December, as well as the tradition of visiting each of the Parish churches on New Year’s Eve for the singing of the Te Deum in a kind of informal procession. To these pre-existing events, the early part of the twentieth century saw the establishment of a procession in honour of Our Lady Help of Christians on 24 March from 1910, and inevitably, given Macao’s status as a Portuguese administered territory, one for Our Lady of Fatima from 1929.13

Events half a world away, once again, made themselves felt in Macao at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Portuguese Revolution of 1910 was “avowedly secular and [one which] persecuted the Catholic Church” (Bruneau 1976, p. 466). It led, amongst other things, to the transfer to the state of ownership of properties owned by religious congregations, which in Macao directly affected several of the churches that marked important points of the various processions, e.g., São Domingos and Santo Agostinho. Under the Lei de Separacão of 1911, public worship was confined to the inside of church buildings, but this does not appear to have been enforced in Macao, although the authorities placed the control of these processions in the hands of the confrarias, even where they had previously been the domain of clerics (Teixeira 1976a). These confrarias had always been a significant element in the various processions-some of which were directly under the patronage of one or other of them-and, although the origins of many of the processions are poorly documented, Teixera’s assumption appears to be that they may well have emerged as initiatives of the confrarias, with the support of individual parochial clergy, rather than as events created by or in response to encouragement from either ecclesial or civil authorities. Even those processions under the control of the civil and ecclesiastical authorities had always involved the significant participation of the confrarias. For example, the announcement in Boletim do Governor for the Corpus Christi procession of 31 May 1866, lists the participation of no fewer than six confrarias (O Boletim Do Governo Em Macau 1866, p. 82). Ljungstedt claims eleven such organisations existed in the early 1830s with others in formation. He notes that they were largely self-governing and financial self-supporting (Ljungstedt 1836, p. 153).

The diocesan Ordem for 1960-a combination of calendar of liturgical and ecclesiastical events, and directory of people and organisations-contains all of the ceremonies listed above, with the exception of that of the Guardian Angel of the Kingdom (Portugal having become a republic in the revolution of 1910),14 and can reasonably be said to record the high-water mark of the pre-Vatican II tide of public piety in Macao. Whatever the truth of Robert Alvis’s claim that “[b]y the 1960s, however, at least in some parts of the Catholic world, enthusiasm for such devotions was in clear decline” (Alvis 2021, p. 2), no such claim can be substantiated with regard to the processions of Macao.

3. Secular Influences

Since the 1949 victory of the Communists at the end of the Chinese Civil War, the position of Macao-dependent entirely on the Mainland for its food and water-had been extraordinarily vulnerable. The small Portuguese garrison in the city had no realistic chances of successfully repulsing a Chinese attack should one have been forthcoming-absent a second intervention from St John the Baptist. This vulnerability was nothing new; in fact, the Portuguese were ever consciousness of the tenuous hold they had on Macao, a concession for which they were required to pay five hundred taels of silver (approximately 610 troy ounces) by way of “rent” (Cheng 1999, p. 23). This had influenced their relations with the Mainland throughout their occupation and was in marked contrast to British claims in respect of Hong Kong. This tenuous hold that the Portuguese had over Macao, one more or less openly acknowledged by all parties, as the events of the latter third of the twentieth century were to demonstrate, made the territory particularly susceptible to influences spreading to it from outside. These influences were to have a direct impact upon the public expressions of Catholic piety, and especially the processions in Macao, in the period leading up to the resumption of Chinese administration in 1999. Two, in particular, require closer consideration: The Cultural Revolution in Mainland China and its overspill in Macao, on the one hand, and the fallout from the Carnation Revolution in Portugal on the other.

In the middle of November 1966, as the Cultural Revolution on the Mainland got into full swing, a dispute over the rebuilding of a school on the island of Taipa turned nasty and, by the beginning of December, it had spread to the Macao peninsular. On 3 December (12-3: the date becoming the name by which the incident would become known, i.e., “One Two Three”) rioting broke out in the centre of Macao with churches and Catholic schools being a particular target. The Portuguese reacted strongly but, after the death of a number of protestors,15 a settlement was brokered in January 1967, in which the Portuguese accepted blame and all but acknowledged that they held Macao as the “caretaker of a condominium under foreign supervision” (Maxwell 2013, p. 279).

The consequences for the Catholic Church were significant. The hurried transfer to Portugal of the diocesan archives has already been noted (Fernandes 2006, p. 48) but Bishop Paulo José Tavares also saw fit to suspend classes at the Diocesan seminary of São José, in 1967, sending the seniors away to complete their training elsewhere and, the following year, dismissing the junior seminarians (Teixeira 1976b, p. 88). Some went to the Holy Spirit Seminary in Hong Kong, others, including José Lai Hung-seng who was to become the second Chinese Bishop of Macao in 2003, were sent to Portugal to complete their studies. The procession of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December did not take place that year, although 12 February the following year, only two weeks after the public ceremony in which Governor José Manuel de Sousa e Faro Nobre de Carvalho had accepted blame on behalf of the Portuguese administration, saw the Bom Jesus procession go ahead as normal. Other processions fared less well: the procession through the surrounding streets, in honour of St Roque, which was particularly associated with the parish church of St Lazarus since an outbreak of plague there in 1889, did not take place after 1966 (or, more accurately, was confined to the interior of the church) until it resumed again 2017, although the solemn Mass continued (O Clarim 2017). The parish of St Lazarus had, since the nineteenth century, been considered the parish for Chinese, as opposed to Portuguese (and Macanese)16 Catholics. The fact that the Mass (inside the Church) for the feast survived whilst the procession (outside) fell into desuetude, might be taken to imply a degree of self-restraint not unconnected with the sensitivity of its predominantly Chinese community to the feelings in the enclave following the events of December 1966.

The next important secular influence on the Catholic public processions of Macao took place nearly 7000 miles away in Portugal. In April 1974, the Second Portuguese Republic (the conservative corporatist, autocratic regime that had ruled Portugal since 1933, and known as the Estado Novo, the name given it by its architect and, until 1968, Prime Minister, António de Oliveira Salazar) collapsed in the face of what was initially a military coup led by largely junior officers who were exhausted by a decade and more of colonial wars. It quickly became a popular movement that came to be called the Carnation Revolution.17 The transition from an authoritarian to (eventually) a democratic state was achieved with remarkably little bloodshed and, with the abandonment of those colonial wars, began a process of decolonization of the Portuguese Empire that could not but affect Macao. With the arrival of a new Governor, José Eduardo Martinho Garcia Leandro in November 1974, the Portuguese were keen to relinquish Macao as it sought to do with its colonies elsewhere. In 1976, even the few Portuguese military personnel permitted to remain in Macao under the agreement of January 1967 were withdrawn from the territory.18 China was not ready to resume administration of Macao but the new legal framework, the Estatuto Orgânico de Macau, adopted by the Portuguese legislature in 1976 gave legal effect to what the previous regime had been forced to concede in 1967: that Macao was Chinese territory under Portuguese administration; in fact that China controlled Macao’s present as much as its future, and the Portuguese were permitted to administer it for as long as it suited the purposes of the People’s Republic, and no longer. This inevitably led to a weakening of Portuguese influence over a population that had tripled since the beginning of the twentieth century, with successive waves of Chinese migrants from the Mainland, and in which the Portuguese and Macanese accounted for less than 5%.

Following a secret agreement between the two countries in 1979 (Hook and Neves 2002, p. 112), by 1987 the broad outlines had been delineated for the retrocession of Macao to Chinese administration, as a Special Administrative Region (“SAR”) of the People’s Republic of China, under the “one country, two systems” principle applied both in Macao and Hong Kong. This took effect on 20 December 1999, at which point the Bishop of Macao-who, since the 1988 appointment of Domingos Lam Ka Tseung, had been Chinese-immediately ceased to be a member of the Portuguese Bishops’ Conference and the diocese became immediately dependent on the Holy See. The Basic Law-the effective constitution of the Macao SAR-provided for a period of fifty years during which freedom of religion is guaranteed (Lei Básica Da Região Administrativa Especial de Macau Da República Popular Da China 1993, art. 34). Macao was now definitively Chinese and the voice of Chinese Catholics would come to have a proper prominence (given their relative number) in all ecclesial affairs, including in the membership of confrarias and, hence, in the organisation of and participation in the processions.

A detailed consideration of the closeness between the Estado Novo and the Catholic Church in Portugal (and, in particular, between Salazar and Manuel Gonçalves Cerejeira, Patriarch of Lisbon from 1929 to 1971), at least after the 1940 Concordat put an end to the tensions of the 1910 settlement, is outside the scope of this article.19 For the present purposes, however, it should be noted that it was distinct from that in Franco’s Spain which saw the closest identification of the one with the other. In Portugal the relationship has been described as “characterized not by cordiality and trust but by suspicion and reserve” (Pereira 2013, p. 407). Nevertheless, whatever the state of the fluctuating warmth between Salazar and Cerejeira,20 between the Estado Novo and the Catholic Bishops, in Macao, Governor and Bishop, as the two most important Portuguese citizens, had had to be seen to be on the same page. This has had a long-lasting legacy during the period under consideration, in the persistent identification of the Catholic Church in Macao with Portuguese interests and has had an impact of all forms of civic engagement (Hao et al. 2014, pp. 15–16). This identification persisted even after the appointment Bishop Domingos and has only begun to fade significantly in the last few years, this despite the part that Lam played as an adviser to the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic, in the drafting of the Basic Law ahead of the handover and the participation of several other clergy in the various advisory and consultative bodies.

Cardinal Cerejeira’s successor as Patriarch, Antonio Ribeiro, had been Bishop of the Portuguese Military before his elevation and was well known to many of those behind the Carnation Revolution. Whilst keen to maintain the Church’s position in Portugal, he had not been close to the Estado Novo regime and, although conservative in political outlook and temperament, in the years following 1974 managed, by a combination of determination, tact and personal connections to navigate what might otherwise have been a very difficult change to accommodate (Thomas 2017). Inevitably Macao continued to be affected by the changes in Portugal but, as in former times when difficulties of communication enforced a time-dampened response, the fall of the Estado Novo had less effect in the concession than elsewhere in the Portuguese world, not least because, unlike in those places affected by the colonial wars, there was no overtly hostile paramilitary opposition. Nevertheless, whilst it may have been a manifestation of the general uncertainty in the immediate fall-out of the events of April 1974 or resulted from other unrecorded factors (not least ecclesial ones), no Corpus Christi procession was held that year: it did not resume until 2017 (Encarnacão 2017).

4. Ecclesial Influences

By the promulgation in 1947 of his Encyclical Letter on the Sacred Liturgy Mediator Dei (Pope Pius XII 1947),21 Pope Pius XII gave a cautious seal of papal approval to much of the thinking and many of the insights of what has come to be called the Liturgical Movement. It was the last of his three major theological encyclicals which in many ways provided much of the magisterial groundwork that made possible the developments at the Second Vatican Council.22 It was not an endorsement of the more advanced ideas of the Liturgical Movement but amongst other things it imported into the explicit Papal Magisterium one of the movement’s key tenets—that the liturgy (understood in the strict sense as those ceremonies directly related to the celebration of the Sacraments or the Liturgy of the Hours, the daily round of fixed formal prayer) should always have priority over devotions. Indeed, whilst explicitly commending certain processions (Pope Pius XII 1947, pp. 132–33) and giving encouragement to the continuation of “other exercises of piety which, although not strictly belonging to the sacred liturgy, are, nevertheless, of special import and dignity” (Pope Pius XII 1947, p. 182), Pope Pius began a trend that is to be frequently encountered in the magisterial documents of the following years, one which might be characterized as a “yes, but” attitude to popular piety: in Pope Pius’s own words,

Hence, he would do something very wrong and dangerous who would dare to take on himself to reform all these exercises of piety and reduce them completely to the methods and norms of liturgical rites. However, it is necessary that the spirit of the sacred liturgy and its directives should exercise such a salutary influence on them that nothing improper be introduced nor anything unworthy of the dignity of the house of God or detrimental to the sacred functions or opposed to solid piety.(Pope Pius XII 1947, p. 184)

In the following paragraphs the Pope insisted that his aim was “that after errors and falsehoods have been removed, and anything that is contrary to truth or moderation has been condemned, you promote a deeper knowledge among the people of the sacred liturgy so that they more readily and easily follow the sacred rites and take part in them with true Christian dispositions”. (Pope Pius XII 1947, p. 186).

This self-same “yes, but” attitude is discernable in the text of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium,23 where devotions are to be commended “provided they accord with the norms and laws of the Church”; have a special dignity “if they are undertaken by mandate of the bishops according to customs or books lawfully approved”; should be “so drawn up that they harmonize with the liturgical seasons, accord with the sacred liturgy, are in some fashion derived from it, and lead the people to it”; and all for the perfectly commendable and theologically sound reason that “the liturgy by its very nature far surpasses any of [those devotions]”. (Sacrosanctum Concilium 1963, p. 13). The palpable sense of a certain disdain expressed here for the enthusiasm that attended many devotions, particularly for those associated with the cult of particular saints or of the Virgin Mary and which often had their origins in legend or apparition, necessitated an attitudinal corrective in Pope Paul VI’s Post-Synodal Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi (Paul VI 1975).24 Yet, Pope Paul’s corrective hardly seems to govern the tone of even the title of the section of the 2001 Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy entitled “Liturgy and Popular Piety: the Current Problematic” (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith 2001, pp. 47–59).25

Whilst this “yes, but” attitude and its consequences have been considered in some detail in the Anglophone world, (see, for example Dolan 2003; Chinnici 2004; Bullivant 2019), its effects have been less well studied in Portuguese-speaking Catholicism, at least outside Brazil. Conversations with those Macao priests trained in Portugal after the events of December 1966, do reveal a tension between attitudes acquired in Portugal during their seminary lives, which reflect similar attitudes to those noted by Dolan in the US (Dolan 2003, pp. 239–40), on the one hand, and their attachment to the familiar popular devotions of their home and their sympathy with now overwhelmingly Chinese parishioners, on the other: parishioners who have taken both the confrarias and the associated processions very much to heart.

Whatever the precise relationship was between a change in the temperature of official ecclesial (or at least clerical) enthusiasm for expressions of devotion and public piety, so far as the processions of Macao are concerned, in addition to those whose demise has already been noted as having some possible connection with other specific events, the conciliar and post-conciliar period saw other processions, such as Our Lady of Remedies at the end of April or the beginning of May, St James, St John the Baptist and Our Lady Help of Christians, fall into desuetude. It seems reasonable to conclude that there may be some connection between the stopping of these processions and a (largely) clerical lack of enthusiasm arising from advanced over-interpretations of the “yes, but” tone of official church teaching. This may also have played a part in the failure to revive those events that had lapsed when the immediate cause for lapsation had passed. The remark of Stephen Bullivant with regard to Mass-going in the US and UK might well be applicable to Macao’s processions: given the Council’s “scale, scope, vision, and ambition…it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Council’s reforms are not casually related to the very significant decline” (Bullivant 2019, pp. 255–56). By the end of the twentieth century, in the year of the return of Macao to Chinese administration, four processions alone survived: Bom Jesus, the Dead Christ, Our Lady of Fatima and St Anthony—all of them firmly under the patronage of particular confrarias. These bodies had, themselves, declined in number, with only six still extant when their existence was last included in the diocesan directory in 2017, and they were no longer the exclusive preserve of Portuguese and Macanese Catholics.

5. Postscript-The Tide Begins to Turn

The second half of the twentieth century saw significant changes in the demographic make-up of the Catholic community in Macao. Waves of migration from China meant an increase in the overall population from just over 196,000 in 1950 to nearly 428,000 in 2000. In 2020 it had risen to 650,000 (Macao Population 1950–2021 2021). The Catholic community which had been predominantly Portuguese, or Macanese is now overwhelmingly Chinese, complemented by Filipino migrant workers who now comprise a significant proportion.

In 2016, the third Chinese Bishop of Macao was appointed. Stephen Lee Bun-sang is a convert to Catholicism and a native of Hong Kong. A year after his taking possession of the diocese, it was he that had restored the Corpus Christi procession, after a period of 43 years (Encarnacão 2017) and his encouragement of the devotions of the Filipino community, with which he had become familiar during his time as the Regional Vicar of Opus Dei in Asia, which has led to the Sinulog Festival, which the Filipinos of the Macao Special Administrative Region had first organised in 2000, acquiring a place in the religious consciousness of the wider Catholic community (Peralta 2020). Despite, or in fact perhaps because of the necessary pandemic precautions, the observance of this festival in 2021, stripped as it had to be of the more exuberant aspects of previous years, concentrated much more significantly upon the Mass and procession of the statue of the Santo Niño than in, at least to the author’s eyes, the previous few years. The changing demographic of Macao’s Catholics has also begun to be been felt in the old established processions. As the proportion of Chinese Catholics continues to rise, their participation and influence has risen in tandem, touching even the arrangements for that most Portuguese of processions, Our Lady of Fatima. In 2018, Bishop Lee changed the order of the languages in which the Rosary which accompanied the procession was prayed, Cantonese replacing Portuguese as the language for the first decade. This was not without controversy amongst those communities who had come to see the procession as an expression not merely of their religious but national and community identity. The author himself witnessed expressions—spoken, written and in social media-of some discomfort, even consternation and anger, at this development amongst certain people in the Catholic community of Macao.

6. Conclusions

In its four and half centuries of Catholic life, Macao’s processions have had a persistent place in public piety. A community that was once largely one made up of expatriate Portuguese and Eurasian Catholics, who had brought their traditional devotions with them from Portugal, often by way of Goa and Malacca, had, by 1960, created a rich tapestry of processions that paraded the religious self-confidence typical of the Catholic Church in the immediate pre-Vatican II period. The fragility of that self-confidence was, however, exposed in reaction to events both secular and ecclesial in the following decade and a half. Processions which had long been fixtures in the religious landscape of Catholic Macao disappeared from the streets. The nature of the political events with which several of these various disappearances coincided was such that it seems not unreasonable to posit a direct causal relationship, even if it is not possible to establish that link with certainty by reference to archival sources at present. That the “collapse of devotionalism” (Chinnici 2004, p. 12) that followed the Second Vatican Council played a part, similarly cannot be discounted either, although the robust survival of processions such as those of the Bom Jesus, the Dead Christ and Our Lady of Fatima is testament to the enduring devotional piety of the Catholics of a now thoroughly Chinese Catholic Macao. In Macao, at least, there is some evidence that pace Chinnici, these devotions express something of a social world which still does to some extent exist (Chinnici 2004, p. 83).

If 1960 represented the high-water mark of the tide of Catholic public piety, at least measured by reference to the number and frequency of religious processions in the enclave, the year of Macao’s return to Chinese administration, after four hundred and forty-three years of Portuguese control, might conceivably be seen as the low-water mark. In 2026, the Diocese of Macao will mark the four hundred and fiftieth anniversary of its establishment. With the re-establishment of several processions that had fallen into desuetude, or had become confined to the inside of churches, the reinvigoration of others and the establishment of still others, it seems certain that the tide of Catholic public piety is once again rising.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvis, Robert E. 2021. The Tenacity of Popular Devotions in the Age of Vatican II: Lerning from Divine Mercy. Religions 12: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. 2012. Jesuits in Macau-450 Years. China Province News. February. (probably Yves Camus SJ). Available online: https://jcapsj.org/sites/default/files/jesuits_in_macau_450_years.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Atchley, Charles. 1905. Ordo Romanus Primus. London: The de la More Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bicalho, Maria Fernandes. 2001. La géographie de l’éspace unrbain global. Arquivos do Centro Cultural Calouste Gulbenkian (Paris) 42: 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, Charles Ralph. 1968. Fidalgos in the Far East 1550–1770, 2nd revised ed. Reprinted with Corrections. Oxford in Asia. Historical Reprints. Hong Kong and London: Oxford U.P. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão, Pedro Ramos. 2003. Salazar-Cerejeira: A ‘Força’ Da Igreja: Cartas Do Cardeal-Patriarca Ao Presidente Do Conselho. Lisboa: Notícias Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, Thomas C. 1976. Church and State in Portugal: Crises of Cross and Sword. Journal of Church and State 18: 463–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2019. Mass Exodus: Catholic Disaffiliation in Britain and America since Vatican II. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Christina Miu Bing. 1999. Macau: A Cultural Janus. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnici, Joseph. 2004. The Catholic Community at Prayer 1926–1976. In Habits of Devotion: Catholic Religious Practice in Twentieth-Century America. Edited by James M. O’Toole. Cushwa Center Studies of Catholicism in Twentieth-Century America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 9–88. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. 2001. Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy. Principles and Guidelines. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20020513_vers-direttorio_en.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- De Camões, Luís, and William C. Atkinson. 1952. The Lusiads. The Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England and New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- de Castelnau-L’Estoile, Charlotte. 2016. The Jesuits and the Political Language of the City: Riot and Procession in Early Seventeenth Century Salvador Da Bahia. In Portuguese Colonial Cities in the Early Modern World. Edited by Liam Matthew Brockey. London: Routledge, pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Denzinger, Heinrich. 2012. Enchiridion Symbolorum, Definitionum et Declarationum de Rebus Fidei et Morum, 43th ed. Edited by Peter Hünermann, Robert Fastiggi and Anne Eglund Nash. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, Jay P. 2003. Search of an American Catholicism: A History of Religion and Culture in Tension. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drnovšek, Jaša. 2018. Early Modern Religious Processions: The Rise and Fall of a Political Genre: Net Structures and Agencies in Early Modern Drama. In Poetics and Politics: Net Structures and Agencies in Early Modern Drama. Edited by Toni Bernhart, Jaša Drnovšek, Sven Thorsten Kilian, Joachim Küpper and Jan Mosch. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encarnacão, José Miguel. 2017. One Body, One Church: The Return of the Corpus Christi Procession. O Clarim, June 23. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Moisés Silva. 2006. Macau Na Política Externa Chinesa, 1949–1979, 1st ed. Lisboa: Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [Google Scholar]

- Foot, Sarah. 2012. Has Ecclesiastical History Lost the Plot? Studies in Church History 49: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Zhidong. 2011. Macau History and Society. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Zhidong, Shing Hing Chan, Wen-ban Kuo, Yik Fai Tam, and Ming Jing. 2014. Case Studies of the Catholic Church in Hong Kong, Macau, Taipei and Shanghai. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 1: 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, Brian, and Miguel Santos Neves. 2002. The Role of Hong Kong Nd Macau in China’s Relations with Europe. The China Quarterly 169: 108–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lach, Donald F. 1994. The Century of Discovery: Book One. Asia in the Making of Europe, 1.1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lei Básica da Região Administrativa Especial de Macau da República Popular da China. 1993. Available online: https://bo.io.gov.mo/bo/i/1999/leibasica/index.asp#c3 (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Ljungstedt, Anders. 1836. An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China; and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China. Boston: James Munroe and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Low Hillard, Harriett. 2002. Lights and Shadows of a Macao Life: The Journal of Harriett Low, Travelling Spinster. Edited by Nan Powell Hodges and Arthur W. Hummel. Woodinville: History Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Macao Population 1950–2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/MAC/macao/population (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Marreiros, Carlos. 1994. Alliances for the Future. Review of Culture 20: 162–72. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Kenneth. 2009. Portugal: “The Revolution of the Carnations”, 1974–75. In Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-Violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Edited by Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 144–61. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Kenneth. 2013. Naked Tropics: Essays on Empire and Other Rogues. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. Available online: http://www.123library.org/book_details/?id=112176 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- McGowan, Anne, and Paul F. Bradshaw, eds. 2018. The Pilgrimage of Egeria: A New Translation of the Itinerarium Egeriae with Introduction and Commentary. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy, Peter. 1919. The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia 1608–1667: Travels in England, Western India, Achin, Macao and the Canton River 1634–1637. Edited by Richard Carnac Temple. London: Hakluyt Society, vol. III–i. [Google Scholar]

- Noticiário Nacional: Procissão Do Senhor Dos Passos Em Macau. 1972. Rádio e Televisão de Portugal. Available online: https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/procissao-em-macau/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- O Boletim Do Governo Em Macau. 1866. Macau: Imprensa Nacional.

- O Boletim Oficial de Macau. 1862. Macau: Imprensa Nacional.

- O Clarim. 2017. Feast of St Roque-Macau’s Proven Protector against the Plague. O Clarim (blog). June 30. Available online: https://www.oclarim.com.mo/en/2017/06/30/feast-of-st-roque-macaus-proven-protector-against-the-plague/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Paul VI. 1975. Post Synodal Apostolic Exhortation ‘Evangelii Nuntiandi’. December 8. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_p-vi_exh_19751208_evangelii-nuntiandi.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Peralta, Rachel Luna. 2020. Sinulog: Filipino Catholics’ Devotion to Santo Niño-Viva Pit Señor! O Clarim. January 23. Available online: https://www.oclarim.com.mo/en/2020/01/23/sinulog-filipino-catholics-devotion-to-santo-nino-viva-pit-senor/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Pereira, Bernardo Futscher. 2013. A Diplomacia de Salazar (1932–1949). Lisbon: Imprensa Dom Quixote. [Google Scholar]

- Pius XII. 1943a. Encyclical Letter ‘Mystici Corporis Christi’. June 29. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_29061943_mystici-corporis-christi.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Pius XII. 1943b. Encyclical Letter ‘Divino Afflante Spiritu’. September 30. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_30091943_divino-afflante-spiritu.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Pius XII. 1947. Encyclical Letter ‘Mediator Dei’. November 20. Available online: http://w2.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_20111947_mediator-dei.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Religions in Macau|PEW-GRF. 2010. Available online: http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/macau#/?affiliations_religion_id=26&affiliations_year=2010®ion_name=All%20Countries&restrictions_year=2016 (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Ryan, Salvador. 2012. Some Reflections on Theology and Popular Piety: A Fruitful or Fraught Relationship?: Some Reflections on Theology and Popular Piety. Heythrop Journal 53: 961–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, Isabel dos Guimarães. 2016. Charity, Ritual, and Business at the Edge of Empire: The Misericódia of Macau. In Portuguese Colonial Cities in the Early Modern World. Edited by Liam Matthew Brockey. London: Routledge, pp. 149–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sacrosanctum Concilium. 1963. Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. Solemnly Promulgated by His Holiness Pope Paul VI on 4 December. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19631204_sacrosanctum-concilium_en.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Simpson, Duncan A. H. 2014. A Igreja Católica e o Estado Novo Salazarista. Lugar Da História 84. Lisboa: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics—Statistics and Census Service. 2020. Government of Macao Special Administrative Region Statistics and Census Service. Available online: https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Statistic?id=1 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Teixeira, Manuel. 1940. Macau e a Sua Diocese. Macau: Tipografia do Orfanato Salesiano, Tipografia da Missão do Padroada, 16 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Manuel. 1976a. Macau e Sua Diocese: As Confrarias Em Macau. Macau: Tipografia da Missão do Padroado, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Manuel. 1976b. Macau e a Sua Diocese: Bispos, Missionários, Igrejas e Escolas. Macau: Tipografia da Missão do Padroado, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Testacci, Bruno, and Erminio Lora. 1992. Concilio Ecumenico Vaticano II: Costituzioni, Decreti, Dichiarazioni, Discorsi e Messaggi. Bologna: Dehoniane. [Google Scholar]

- The Historian of the City of the Mother of God, Father Manuel Teixeira. 1982. Itinerario 6: 25–42. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Maria. 2017. Catholicism and the End of Dictatorship in Portugal and Spain: Convergences and Contrasts. Bulletin of Spanish Studies 94: 1533–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Clive. 2001. Camões, China and Macau. Portuguese Studies 17: 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, John E. 1998. Relations with Maritime Europe: 1514–1662. In The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644: Part 2. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Frederick W. Mote. The Cambridge History of China 8. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 333–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, George H. C. 1987. 澳門史-History of Macao. Hong Kong: Commerical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zhiliang, and Yunzhong Yang, eds. 2005. 澳門百科全書-Enciclopédia de Macau. Macao: Fundacão Macau. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The 1991 census giving the figure as 6.7% (Hao 2011, pp. 121–22) and the Pew Survey of 2010 suggesting 5.3% (Religions in Macau|PEW-GRF 2010). The1991 census figures include only the religious affiliation of Macao residents. It is likely that above 90% of the Filipino non-resident workers are also Catholics. The 1991 census recorded 14,544 Filipino born non-resident worked and, by 2020, this figure had risen to over 31,600 (Statistics—Statistics and Census Service 2020). |

| 2 | For all practical purposes, the confrarias are organised in a largely similar way and for the same purposes (mutual assistance, practical and spiritual, social and religious) as their counterparts across the Iberian peninsular. In many respects they share common characteristics with the confraternities, guilds and stores found across late-Medieval and Early Modern Europe. |

| 3 | It is impossible to overstate the importance of Fr Teixeira (1912–2003) as an historian of Macao. Despite his rather sparing approach to the citation of his sources, his sixteen volume Macau e a sua Diocese, published between 1940 and 1979 (Teixeira 1940), stands peerless in its scope and depth as an account of the history of Macao. An illuminating account of his work is to be found in (The Historian of the City of the Mother of God, Father Manuel Teixeira 1982). |

| 4 | One such potential source, Conego José Kou Tin Yau (1925–1921), the last of the Macao clergy to have been ordained early enough to have had extensive first-hand experience of the pre-conciliar practice, was taken ill and died during the writing of this article. |

| 5 | In modern Portuguese orthography “Macau”, from the Chinese “A-Ma Gau”, meaning “Bay of A-Ma”. |

| 6 | For a fuller introduction to the Padroado Real Portuguesa, see (Lach 1994, pp. 230–45). |

| 7 | Ljungstedt records that the Senado of Macao had advised King Philip (I of Portugal, II of Spain-this during the union of the Kingdoms) that City already had “a Cathedral with two parishes, a Misericordia with two hospitals and four religious bodies, viz: Augustinians, Dominicans, Jesuits and Capuchins.” (Ljungstedt 1836, p. 155). An introduction to the history of early Catholic Macao can be found in the first four volumes of (Teixeira 1940). |

| 8 | The author is firmly committed to a proper “religious turn” in the history of religious belief and practice, indeed in history in general, and would align himself very firmly with the sentiments expressed by Sarah Foot in ‘Has ecclesiastical history lost the plot’ (Foot 2012). |

| 9 | Atkinson’s introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Lusiads, for example, assumes this to be so and stands as a representative of this commonly held position (De Camões and Atkinson 1952, p. 18), although others are less convinced: see, for example (Boxer 1968, p. 32). Perhaps the most that can be said is, as Clive Willis has observed, “That [Camões] lived in Macau in the late 1550s I consider to be beyond doubt. Whether he composed his verses in the gruta de Camões it is impossible to judge.” (Willis 2001, p. 99). |

| 10 | The Dutch had attempted to capture Macao on several occasions but were definitively defeated in a battle on 24 June 1622, the Feast of St John the Baptist, leaving (according to Mundy (1919, III–i:268)) 500 or 600 hundred dead. The victory was attributed to the Saint’s intercession (although the quality of the gunnery of Fr Giacomo Rho SJ played a part and he was immediately acclaimed the patron of the City (Boxer 1968, p. 125). Anders Ljungstedt makes mention of the procession in (Ljungstedt 1836, p. 154). The day was observed until the hand-over to China in 1999 (Wu and Yang 2005, p. 482). |

| 11 | Fr Teixeira can be seen at the rear (left hand side) of the procession of priests, at the very end of the film at 2′43′′. |

| 12 | Low’s accounts of the processions, in particular, reveal her strong New England Unitarian sensibilities in her revulsion at these Catholic devotions, describing the ceremonies as “wretched”, “mockery” (twice), “a farce”, “horrid”, “really quite dreadful” and making “her blood run cold” (Low Hillard 2002, pp. 107, 108, 136, 211, 316). |

| 13 | The apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Fátima, central Portugal, in 1917, quickly acquired widespread popularity in Portugal and her colonies. They were widely seen in apocalyptic terms, variously related to the First World War, in which Portugal was a participant in alliance with Britain, France and (from 1917) the USA, the Russian Revolution of that same year, and the anti-clericalism of the Portuguese First Republic. It is unsurprising that the Portuguese Catholics of Macao would quickly develop an attachment to the devotion. In 1940, as the Sino-Japanese War surrounded Macao and the stand-off between Portugal and the Holy See was resolved by a concordat, the Catholics of Macao enshrined and crowned a statue of Our Lady of Fatima in the Cathedral of the city, under the title Queen of Portugal. |

| 14 | The subsequent renaming of this day as the Day of Camões-supposedly it is also the date of the poet’s death (another contested element of his legacy)-has not, itself, been free from politically influenced change. It was referred to as the Dia da Raça (the Day of the [Portuguese] Race) by António de Oliveira Salazar, the Prime Minister of the authoritarian Estado Novo regime from 1932 to 1968, and, following the fall of that regime in the 1974 Carnation Revolution, has now settled into the lengthy, if more liberal, appelation of “The Day of Portugal, Camões and the Portuguese Communities”. |

| 15 | The precise figure is disputed. The official tally reported in the press was three but there is evidence of as many as eight (Wong 1987, p. 198; Hao 2011, p. 215). |

| 16 | “Macanese”, or in Portuguese “Macaenses” is a contested term refering to those of mixed Portuguese and Asian ancestry (or aspiration). See (Marreiros 1994). |

| 17 | For a concise account of this event, see (Maxwell 2009). |

| 18 | The author was recently told, by Jorge Neto Valente, a former Portuguese Cavalry Office, later Legislative Assembly Member under the post-1999 Macao SAR settlement and current President of the Macao Lawyers Association, that Portugal had been permitted to retain its seven armoured cars in Macao after 1967, but the agreement stipulated that they were not to be taken out onto the public street. (conversation, 22 January 2021). |

| 19 | For just such a consideration, see (Simpson 2014). |

| 20 | The growing coolness in the relations between the two men is observable in their correspondence-particularly in the previously unpublished letters, now available in Pedro Ramos Brandão’s 2003 book (Brandão 2003). |

| 21 | An Encyclical Letter is an authoritative teaching document of the Pope in epistolary form, addressed to the bishops and superiors of religious orders and congregations. These documents, which often have very long formal titles (Mediator Dei itself is formally called “Encyclical of Pope Pius XII on the Sacred Liturgy to the Venerable Brethren, the Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, Bishops, and Other Ordinaries in Peace and Communion with the Apostolic See”) and are, therefore, commonly known by the first two or three Latin words of the text of the encyclical. Mediator Dei means “The mediator of God”. |

| 22 | The others being Mystici Corporis on the nature of the Church (Pius XII 1943a) and Divino Afflante Spiritu on Sacred Scripture (Pope Pius XII 1943b). The magisterium of Pius XII is, after Sacred Scripture, the most frequently quoted source in the documents of the Second Vatican Council (Testacci and Lora 1992, pp. 608–9). |

| 23 | Meaning “This Sacred Council”, from the opening phrase of the document “This Sacred Council has several aims in view”. |

| 24 | A “Post-Synodal Exhortation” is another type of teaching document issued by popes following and in response to meetings of synods of bishops. Of a lower authority than an encyclical, it is however, considered to be an authoritative expression of the teaching of the Catholic Church. Evangelii Nuntiandi means “to proclaim the Gospel”. |

| 25 | Salvador Ryan describes the creative tension between the two well when he suggests that if the correct balance is struck, rather than the disdainful regard of the one for the other, the in a “process of embodiment and expression, doctrine becomes inculturated and nuanced”. (Ryan 2012, p. 969). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).