From Secular to Sacred: Bringing Work to Church

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Filling the Gap

2. Methods and Data

3. Results

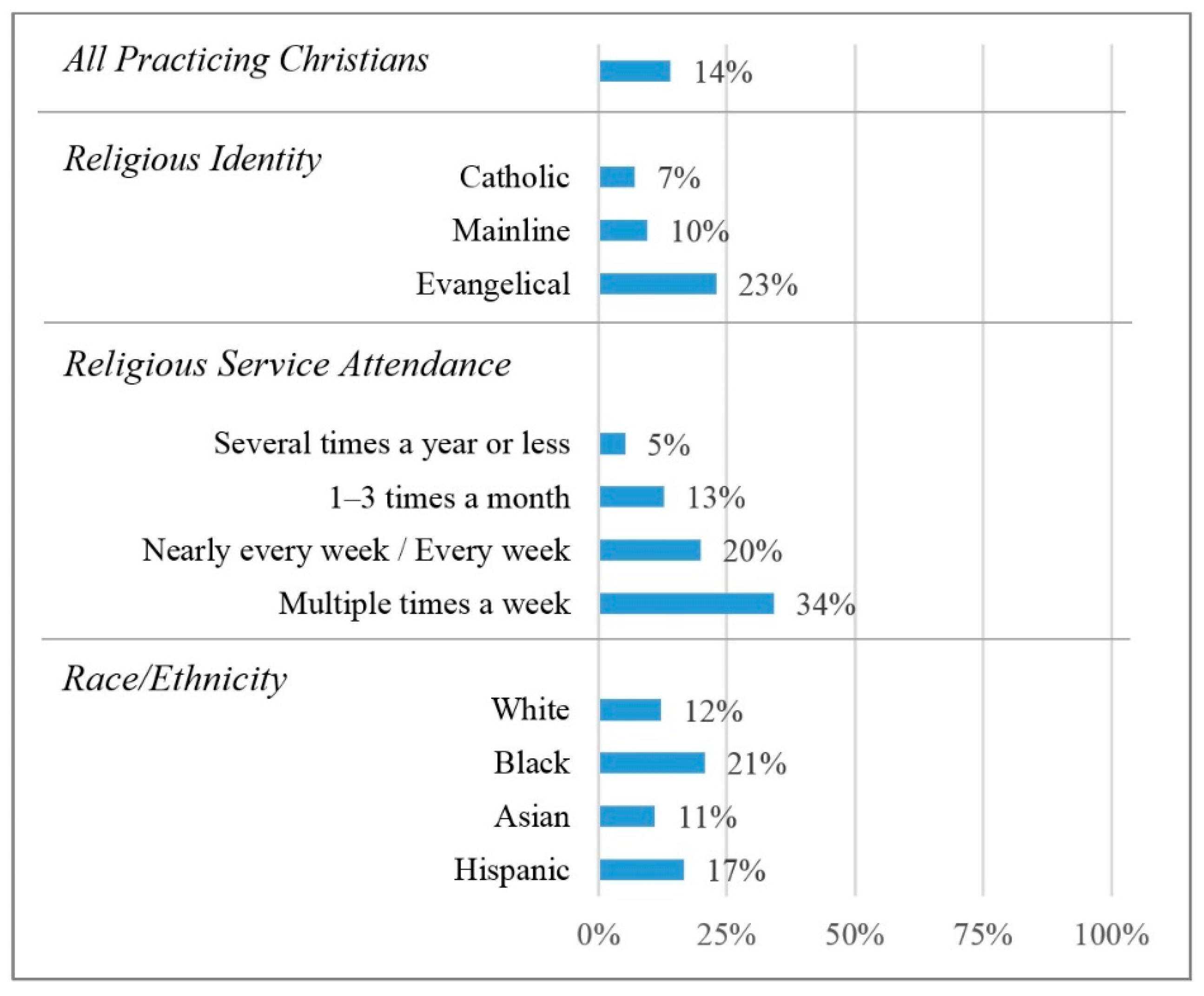

3.1. Survey Findings

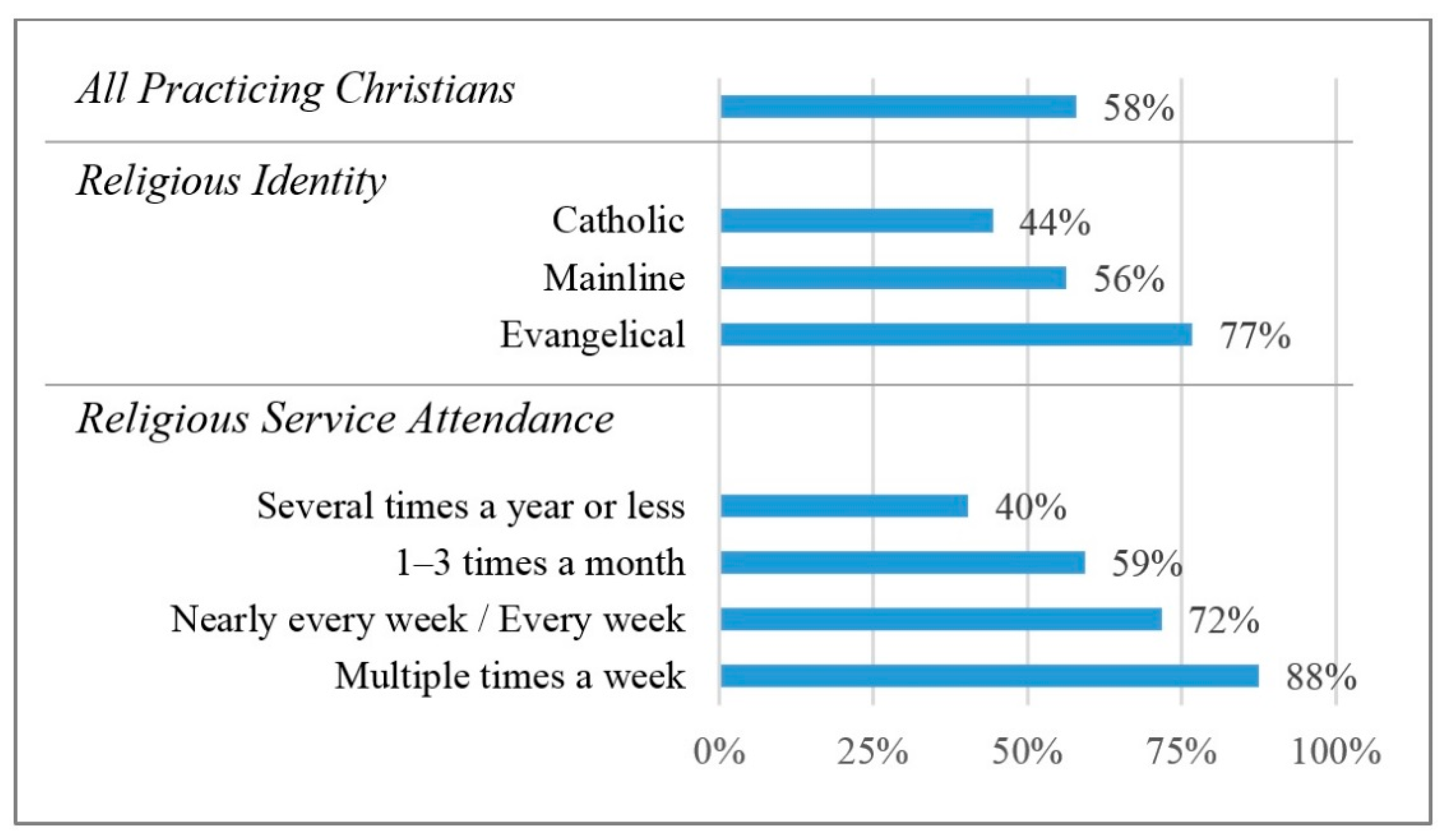

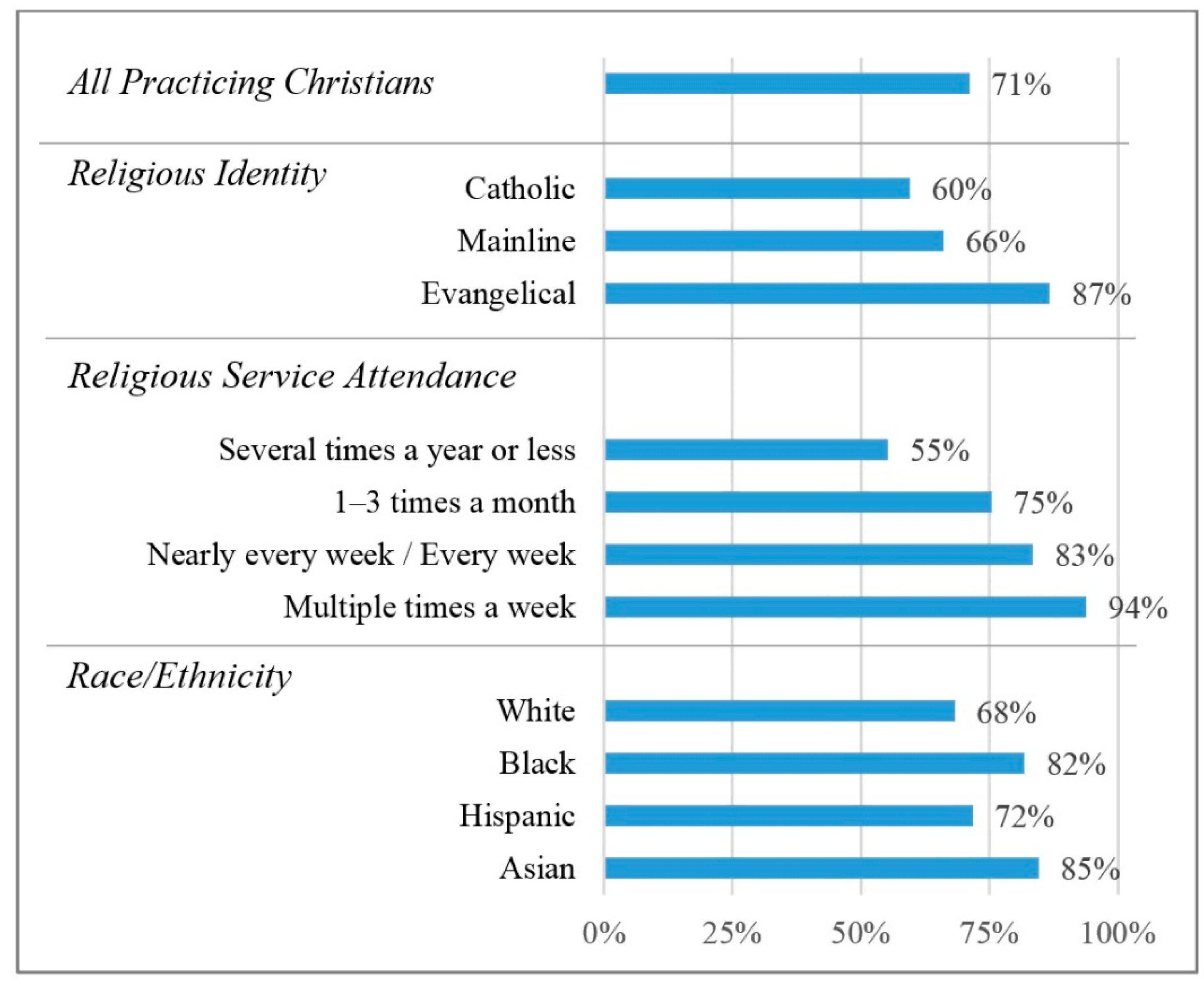

3.1.1. Impact of Faith Community on Workplace Success

3.1.2. Talking about Work at Church

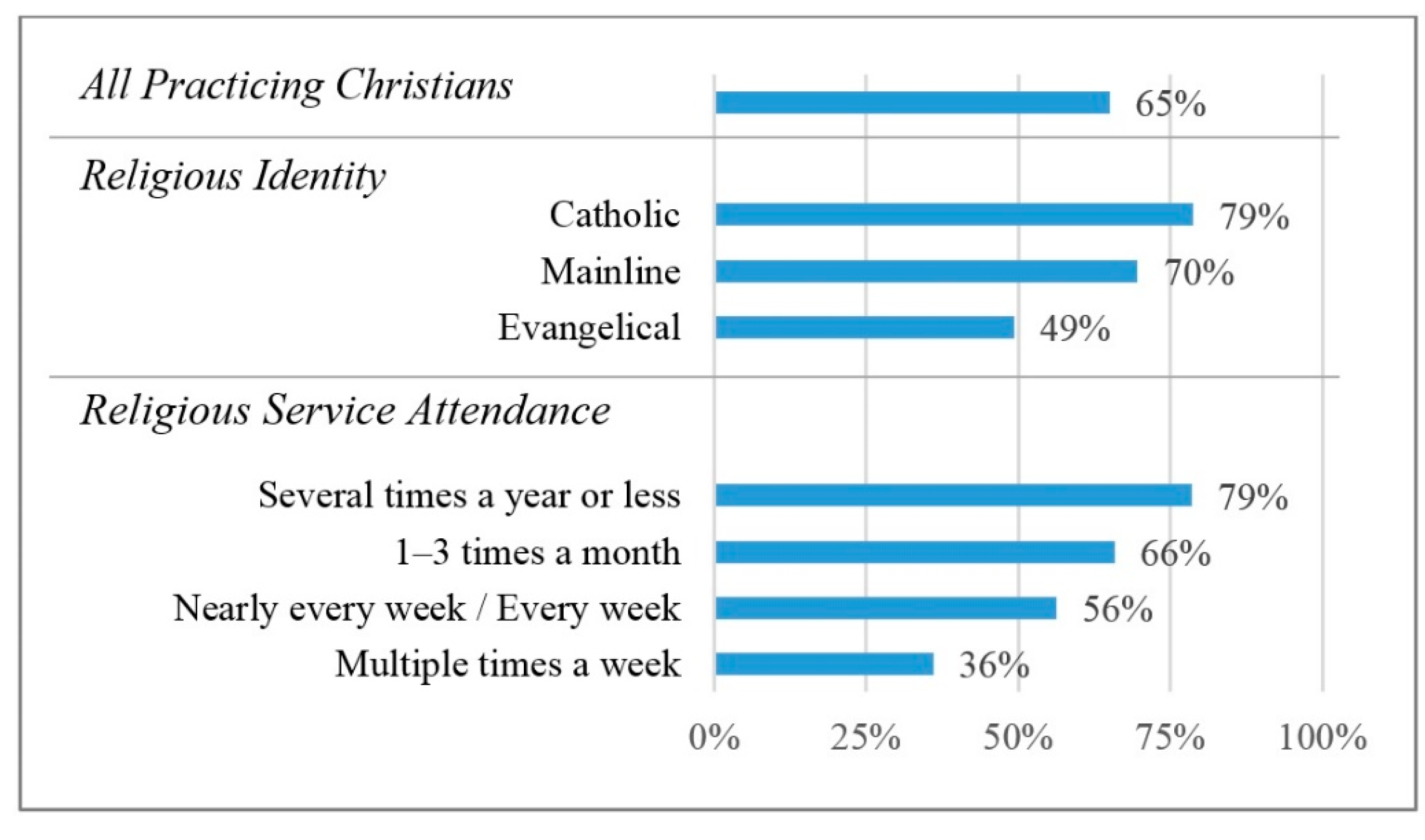

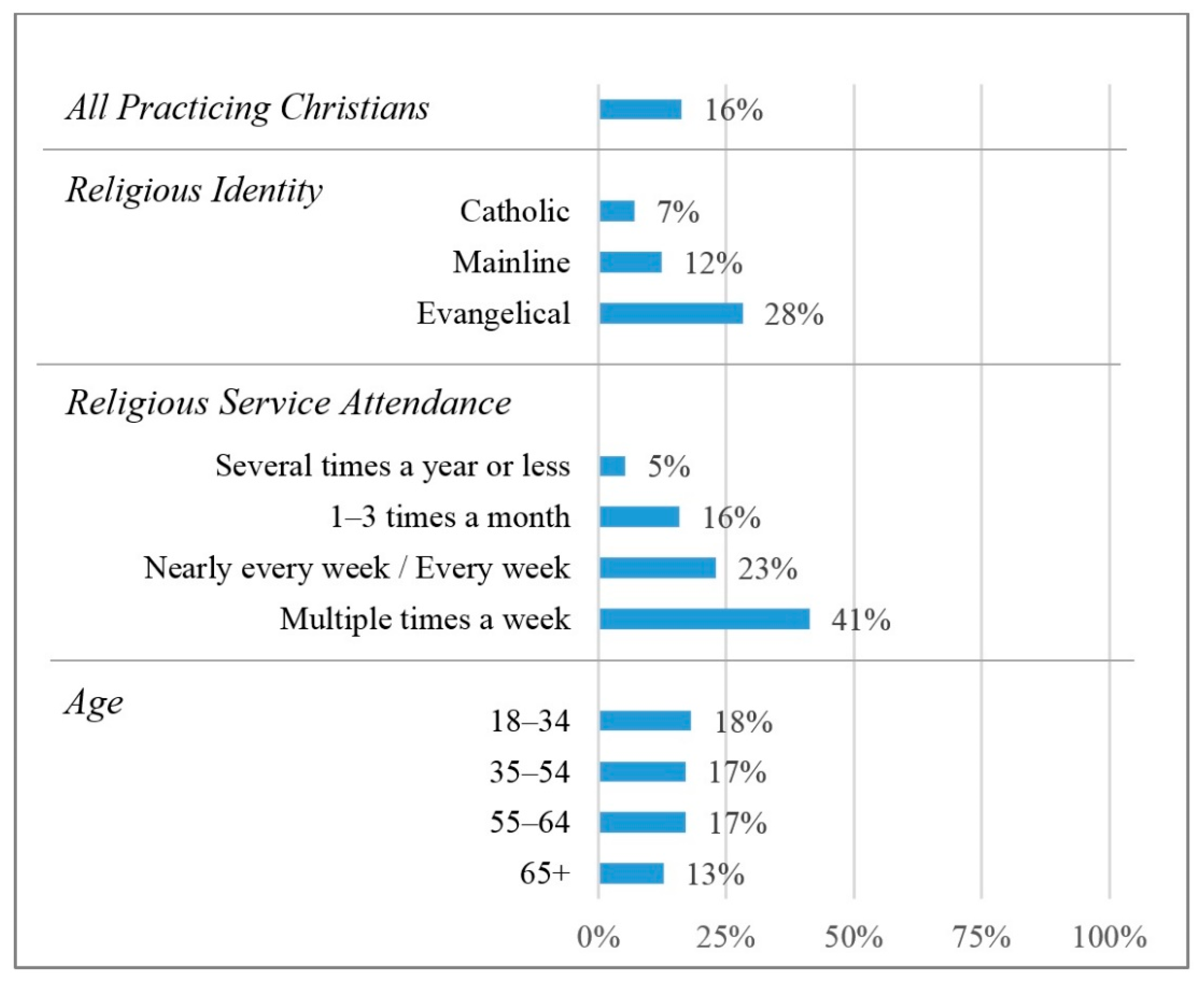

3.2. Interview Findings

3.2.1. Encourage and Support Workers

Affirm the Spiritual Value, Meaning, and Purpose of Work

I think that the best thing that we can do as congregation leaders, as faith leaders, is to remind people that every single one of them has value, and the way that you are contributing to the world is the way that God has asked you to, and that that has value. [...] And so I think the answer has to do with helping people find dignity and value in what it is that they do.8

Pay Attention to Those Who Struggle: Challenging Professions, Women, and Job Seekers

I think unfortunately, very few pastors have been in the work world. And I think it’s hard to relate. I know pastors have very demanding lives because of what they do, but in a lot of ways their schedules are pretty flexible too. That same thing is not true in the work world. And so, I’ve definitely seen situations with what I’d say a lack of empathy or understanding towards just how demanding work can be. And I don’t know that a lot of pastors realize that. I mean I think intellectually they know it, but I don’t think they get it.27

3.2.2. Provide Guidance for Engaging Faith at Work

Expressing Their Own Faith

I think sometimes people will shy away because everyone’s always scared of breaking a law that there’s a lawsuit coming or something that I think sometimes we just shy away from everything. So I think it would be good to understand in the faith side or in the church side, and also for the senior leaders to be able to better articulate, ‘Hey, this is acceptable and this isn’t.’52

I think, that pastors and religious leaders should help teach them using the dictates of their religion, teach them how to respond in a way that is honoring to the religion. You know, not to respond as—in a secular manner, but act in a way that will bring honor to God. I think that’s something that all—that definitely all Christians need to learn. I think—like I said, I think a lot of us, we tend to react instinctively because I think a lot of us just aren’t—it’s never discussed in church, I think, for a lot of people. […] When it comes up, they don’t know how to respond. They’re either—they either get angry, or they get scared, or they just get so nervous that they fall over themselves, and I don’t think that’s—I don’t think that’s the way that Christ wants us to respond. I think he wants us to respond in a way that’s measured, and it comes out of knowledge, not out of fear.54

3.2.3. Minister to Working People at Church

Flexible Offerings

Hospitable Church Environment

4. Discussion/Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Religious Identity | Religious Service Attendance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faith and Work Variables | Overall ♦ | Catholic | Evang. | Mainline | Other | Chi-Sq. | Several Times per Year or Less | 1–3 Times per Month | Nearly Every Week/Every Week | Multiple Times per Week | Chi-Sq. |

| Skills and habits that I have learned from my faith community help me succeed at work. ◊ | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 8.4 | 12.5 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 8.3 | * | 12.6 | 9.5 | 4.7 | 1.0 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 4.6 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 2.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 20.4 | 24.9 | 14.7 | 21.4 | 21.2 | 23.6 | 23.1 | 18.4 | 9.7 | ||

| Somewhat agree | 30.0 | 29.0 | 30.1 | 33.6 | 29.3 | 28.8 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 23.3 | ||

| Strongly agree | 27.9 | 15.4 | 46.7 | 22.8 | 24.3 | 11.7 | 26.7 | 39.3 | 64.3 | ||

| I do not have a faith community | 8.6 | 11.7 | 2.4 | 6.8 | 12.4 | 16.8 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 0.5 | ||

| My faith guides me through stressful times in my work-life. ◊ | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 4.0 | 7.0 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 3.8 | * | 6.8 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 0.1 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 3.2 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 13.7 | 18.9 | 7.2 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 21.4 | 12.1 | 7.5 | 2.4 | ||

| Somewhat agree | 27.2 | 28.5 | 23.2 | 32.0 | 27.5 | 30.9 | 33.2 | 24.0 | 14.1 | ||

| Strongly agree | 43.9 | 31.1 | 63.6 | 34.2 | 41.8 | 24.4 | 42.2 | 59.5 | 79.8 | ||

| This does not apply to me | 8.1 | 10.0 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 3.6 | ||

| My faith community supports me in my work or career. ◊ | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 6.2 | 10.6 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 5.9 | * | 9.3 | 6.5 | 3.6 | 1.3 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 3.0 | 4.2 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 2.2 | 1.0 | ||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 30.6 | 34.5 | 27.5 | 32.5 | 29.1 | 33.1 | 35.8 | 28.8 | 19.0 | ||

| Somewhat agree | 17.0 | 13.4 | 22.2 | 18.5 | 14.6 | 10.0 | 21.8 | 23.3 | 19.7 | ||

| Strongly agree | 24.5 | 12.9 | 39.4 | 22.3 | 22.2 | 8.9 | 22.1 | 36.5 | 56.0 | ||

| I do not have a faith community | 18.7 | 24.4 | 7.0 | 16.6 | 25.6 | 35.2 | 8.9 | 5.6 | 3.1 | ||

| How often do you participate in discussion groups about faith and work? | |||||||||||

| Not at all | 65.0 | 78.7 | 49.3 | 69.7 | 64.9 | * | 78.6 | 65.8 | 56.3 | 36.0 | * |

| Less than once per month | 18.0 | 12.3 | 24.0 | 17.2 | 18.0 | 14.4 | 21.3 | 20.5 | 20.5 | ||

| 1–2 times per month | 8.3 | 5.0 | 12.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 4.3 | 8.8 | 11.9 | 13.1 | ||

| 3–4 times per month | 4.8 | 2.0 | 8.5 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 15.0 | ||

| 5 or more times per month | 3.9 | 2.0 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.2 | 15.5 | ||

| My faith leader discusses how we should behave at work. | |||||||||||

| Never | 15.1 | 19.4 | 9.6 | 18.7 | 14.6 | * | 15.9 | 20.5 | 14.8 | 5.6 | * |

| Rarely | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 15.0 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 15.6 | 13.8 | 9.7 | ||

| Sometimes | 24.6 | 18.7 | 34.3 | 23.3 | 21.6 | 13.1 | 29.7 | 33.6 | 36.5 | ||

| Often | 10.2 | 4.6 | 17.1 | 7.6 | 10.0 | 3.6 | 10.2 | 14.5 | 24.1 | ||

| Very often | 6.2 | 2.5 | 11.1 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 17.3 | ||

| I do not have a faith leader | 33.7 | 44.7 | 17.6 | 30.8 | 39.9 | 59.7 | 18.4 | 14.7 | 6.9 | ||

| My faith leader teaches about the meaning of work. | |||||||||||

| Never | 13.7 | 18.1 | 9.7 | 15.7 | 12.5 | * | 15.5 | 16.4 | 13.0 | 4.8 | * |

| Rarely | 11.7 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 16.2 | 10.0 | 6.6 | 16.8 | 15.6 | 13.2 | ||

| Sometimes | 26.8 | 19.2 | 37.9 | 27.8 | 23.1 | 13.6 | 34.3 | 36.5 | 40.4 | ||

| Often | 9.3 | 5.9 | 14.6 | 6.3 | 8.9 | 4.0 | 8.3 | 13.3 | 19.8 | ||

| Very often | 4.8 | 1.3 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 14.5 | ||

| I do not have a faith leader | 33.7 | 44.4 | 17.7 | 30.6 | 40.1 | 59.1 | 19.7 | 14.9 | 7.3 | ||

| Faith and Work Variables | Overall ♦ | Gender | Race/Ethnicity | Age | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Woman | Chi-Sq. | White ○ | Black | Asian | Hispanic | Other | Multiple | Chi-Sq. | 18–34 | 35–54 | 55–64 | 65+ | Chi-Sq. | ||

| Skills and habits that I have learned from my faith community help me succeed at work. ◊ | ||||||||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 8.4 | 9.5 | 7.3 | * | 8.5 | 7.1 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.8 | * | 9.6 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 7.8 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 4.6 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.8 | |||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 20.4 | 20.3 | 20.4 | 20.8 | 17.7 | 13.5 | 19.1 | 29.0 | 21.1 | 18.1 | 19.1 | 19.8 | 25.3 | |||

| Somewhat agree | 30.0 | 29.8 | 30.4 | 30.2 | 30.8 | 33.4 | 32.7 | 24.1 | 25.8 | 31.0 | 30.0 | 28.5 | 30.4 | |||

| Strongly agree | 27.9 | 27.0 | 29.0 | 26.5 | 36.0 | 28.4 | 25.8 | 27.0 | 30.7 | 26.5 | 30.7 | 30.4 | 23.2 | |||

| I do not have a faith community | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 5.5 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 2.8 | 10.0 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.6 | |||

| My faith guides me through stressful times in my work-life. ◊ | ||||||||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 4.0 | 5.0 | 2.9 | * | 4.1 | 2.0 | 8.4 | 6.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | * | 5.6 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 3.2 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 1.7 | |||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 13.7 | 16.2 | 11.3 | 15.4 | 6.6 | 2.0 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 12.7 | 16.8 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 12.4 | |||

| Somewhat agree | 27.2 | 29.5 | 25.1 | 27.7 | 24.6 | 31.5 | 27.6 | 31.6 | 27.1 | 30.3 | 27.9 | 25.1 | 24.7 | |||

| Strongly agree | 43.9 | 39.0 | 48.8 | 40.6 | 57.2 | 53.1 | 44.2 | 56.1 | 46.5 | 38.6 | 47.6 | 48.9 | 39.8 | |||

| This does not apply to me | 8.1 | 6.8 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 7.0 | 18.3 | |||

| My faith community supports me in my work or career. ◊ | ||||||||||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 6.2 | 7.0 | 5.5 | * | 5.8 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 7.0 | * | 4.8 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.7 | * |

| Somewhat disagree | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 10.9 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | |||

| Neither disagree nor agree | 30.6 | 31.7 | 29.6 | 31.5 | 28.0 | 17.3 | 27.6 | 24.4 | 31.5 | 25.9 | 29.3 | 32.8 | 35.9 | |||

| Somewhat agree | 17.0 | 17.3 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 18.2 | 35.6 | 17.5 | 22.4 | 15.7 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 15.4 | 14.5 | |||

| Strongly agree | 24.5 | 23.4 | 25.5 | 24.2 | 27.6 | 20.9 | 24.9 | 30.7 | 21.5 | 26.9 | 24.6 | 25.0 | 21.4 | |||

| I do not have a faith community | 18.7 | 17.7 | 19.6 | 19.1 | 15.5 | 9.5 | 19.8 | 6.7 | 21.5 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 19.0 | 17.8 | |||

| How often do you participate in discussion groups about faith and work? | ||||||||||||||||

| Not at all | 65.0 | 66.5 | 63.8 | * | 64.7 | 63.4 | 65.1 | 67.0 | 62.3 | 66.6 | * | 62.1 | 64.3 | 65.3 | 68.8 | * |

| Less than once per month | 18.0 | 18.3 | 17.7 | 18.7 | 15.7 | 25.7 | 17.2 | 25.0 | 15.9 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 17.7 | 14.5 | |||

| 1-2 times per month | 8.3 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 6.8 | |||

| 3-4 times per month | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | |||

| 5 + times per month | 3.9 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.8 | |||

| My faith leader discusses how we should behave at work. | ||||||||||||||||

| Never | 15.1 | 14.6 | 15.4 | ns | 15.2 | 15.3 | 12.0 | 14.9 | 17.8 | 13.4 | * | 11.7 | 13.3 | 15.7 | 20.9 | * |

| Rarely | 10.3 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 26.0 | 10.3 | 16.9 | 8.6 | 12.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 9.2 | |||

| Sometimes | 24.6 | 24.2 | 24.7 | 24.4 | 25.4 | 22.9 | 24.0 | 18.2 | 25.5 | 26.7 | 26.4 | 23.4 | 20.6 | |||

| Often | 10.2 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 11.7 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 18.0 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 7.4 | |||

| Very often | 6.2 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 11.8 | 2.0 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 5.3 | |||

| I do not have a faith leader | 33.7 | 33.6 | 33.9 | 35.1 | 26.0 | 29.2 | 34.5 | 23.9 | 35.3 | 31.0 | 33.5 | 34.0 | 36.7 | |||

| My faith leader teaches about the meaning of work. | ||||||||||||||||

| Never | 13.7 | 14.8 | 12.7 | * | 13.6 | 14.5 | 9.0 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 13.0 | * | 9.8 | 12.6 | 15.2 | 18.2 | * |

| Rarely | 11.7 | 12.0 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 10.4 | 17.1 | 11.5 | 15.5 | 8.9 | 13.1 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 12.0 | |||

| Sometimes | 26.8 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 28.4 | 32.0 | 23.5 | 27.7 | 28.7 | 29.3 | 27.7 | 26.2 | 23.3 | |||

| Often | 9.3 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 11.3 | 9.1 | 11.0 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 8.2 | 5.9 | |||

| Very often | 4.8 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 4.3 | |||

| I do not have a faith leader | 33.7 | 33.7 | 33.7 | 35.1 | 26.0 | 30.9 | 34.7 | 22.8 | 35.7 | 31.4 | 33.7 | 33.4 | 36.4 | |||

References

- Ammons, Samantha K., and Penny Edgell. 2007. Religious Influences on Work–Family Trade-Offs. Journal of Family Issues 28: 794–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammons, Samantha K., Eric C. Dahlin, Penny Edgell, and Jonathan Bruce Santo. 2017. Work-Family Conflict among Black, White, and Hispanic Men and Women. Community, Work & Family 20: 379–404. [Google Scholar]

- Civettini, Nicole H. W., and Jennifer Glass. 2008. The Impact of Religious Conservatism on Men’s Work and Family Involvement. Gender & Society 22: 172–93. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, James C., and David P. Caddell. 1994. Religion and the Meaning of Work. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerath, Nicholas Jay, III, and Terry Schmitt. 1998. Transcending Sacred and Secular: Mutual Benefits in Analyzing Religious and Nonreligious Organizations. In Sacred Companies: Organizational Aspects of Religion and Religious Aspects of Organizations. Edited by Nicholas Jay Demerath, III, Peter Dobkin Hall, Terry Schmitt and Rhys H. Williams. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Demerath, Nicholas Jay, III, Peter Dobkin Hall, Terry Schmitt, and Rhys H. Williams. 1998. Sacred Companies: Organizational Aspects of Religion and Religious Aspects of Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Kevin D., Jenna Griebel, Mitchell J. Neubert, and Jerry Z. Park. 2013. A Religious Profile of American Entrepreneurs. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 401–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny. 2006. Religion and Family in a Changing Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and John Bartkowski. 2002. Conservative Protestantism and the Division of Household Labor among Married Couples. Journal of Family Issues 23: 950–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Jennifer A., M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall, Tamara L. Anderson, and Kerris L. M. Del Rosario. 2013. A Mixed-Methods Exploration of Christian Working Mothers’ Personal Strivings. Journal of Psychology & Theology 41: 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Don, Kathleen O’Neil, and Laura Stephens. 2004. Spirituality in the Workplace: New Empirical Directions in the Study of the Sacred. Sociology of Religion 65: 265–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebel, Jenna M., Jerry Z. Park, and Mitchell J. Neubert. 2014. Faith and Work: An Exploratory Study of Religious Entrepreneurs. Religions 5: 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. Elizabeth Lewis, Kerris L.M. Oates, Tamara L. Anderson, and Michele M. Willingham. 2012. Calling and Conflict: The Sanctification of Work in Working Mothers. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Stephen, and David Krueger. 1992. Faith and Work: Challenges for Congregations. The Christian Century 109: 682–86. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Timothy, and Katherine Leary Alsdorf. 2012. Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Brother, and Joseph de Beufort. 1908. The Practice of the Presence of God. New York: F.H. Revell. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Monty L., Michael J. Naughton, and Steve VanderVeen. 2010. Connecting Religion and Work: Patterns and Influences of Work-Faith Integration. Human Relations 64: 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Matthew, and Jeremy Reynolds. 2018. Religious Affiliation and Work–Family Conflict among Women and Men. Journal of Family Issues 39: 1797–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, Peter. 2019. Integrating Christian Spirituality at Work: Combining Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches. Religions 10: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, David W. 2003. The Faith a Work Movement. Theology Today 60: 301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, David W. 2007. God at Work: The History and Promise of the Faith at Work Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David W., and Timothy Everest. 2013. Faith at Work (Religious Perspectives): Protestant Accents in Faith and Work. In Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace. Edited by Judi Neal. New York: Springer, pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Laura, and Scotty McLennan. 2001. Church on Sunday, Work on Monday: The Challenge of Fusing Christian Values with Business Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, Michael J. 2019. Getting Work Right: Labor and Leisure in a Fragmented World. Steubenville: Emmaus Road Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Neubert, Mitchell J., Kevin D. Dougherty, Jerry Z. Park, and Jenna Griebel. 2013. Beliefs about Faith and Work: Development and validation of Honoring God and Prosperity Gospel Scales. Review of Religious Research 56: 129–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, Michael. 1996. Business as Calling: Work and the Examined Life. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jerry Z., Jenna Griebel Rogers, Mitchell J. Neubert, and Kevin D. Dougherty. 2014. Workplace-Bridging Religious Capital: Connecting Congregations to Work Outcomes. Sociology of Religion 75: 309–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Jeremy, and Matthew May. 2014. Religion, Motherhood, and the Spirit of Capitalism. Social Currents 1: 173–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Jenna Griebel, and Aaron B. Franzen. 2014. Work-Family Conflict: The Effects of Religious Context on Married Women’s Participation in the Labor Force. Religions 5: 580–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitle, Christopher P., and Kevin D. Dougherty. 2008. The Sociology of Religious Organizations. Sociology Compass 2: 981–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren E. 2000. ‘That They Be Keepers of the Home’: The Effect of Conservative Religion on Early and Late Transitions into Housewifery. Review of Religious Research 41: 344–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Natalie Pickering, Joo Yeon Shin, and Bryan J Dik. 2010. Calling in Work: Secular or Sacred? Journal of Career Assessment 18: 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Susan Crawford. 2006. The Work-Faith Connection for Low-Income Mothers: A Research Note. Sociology of Religion 67: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duzer, Jeffrey B. 2010. Why Business Matters to God: (And What Still Needs to be Fixed). Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Volf, Miroslav. 1991. Work in the Spirit: Toward a Theology of Work. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alan G. 2013. The Relationship between the Integration of Faith and Work Integration with Life and Job Outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 112: 453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 1930. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1997. The Crisis in the Churches: Spiritual Malaise, Fiscal Woe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Examples include Redeemer Presbyterian Church’s Center for Faith and Work (NY); The Denver Institute for Faith and Work, The Nashville Institute for Faith and Work; Flourish San Diego; 4Word Women; C12’s Christian Business Advisory Peer Groups; C3 Leaders; Christian Business Men’s Connection (CBMC); the Theology of Work Project; and many others. |

| 2 | While this genre tends towards Protestant theological perspectives, Novak (1996) and Naughton (2019) write from a Catholic perspective. Historically, within Catholic contemplative traditions, reflection on work has also been a prominent theme, such as the teachings of Brother Lawrence (Lawrence and de Beufort 1908). |

| 3 | As noted, a few older studies have explored empirically how church members perceive workplace support from clergy and in their churches (Hart and Krueger 1992; Nash and McLennan 2001; Wuthnow 1997). Utilizing interviews and surveys, these studies have found that, on the whole, respondents report that clergy rarely address the topic of work at church, and church members rarely discuss work concerns with their pastors. Yet these studies are quite dated and limited in scope. Often, they are primarily focused on white middle-class Protestant Christians limiting their generalizability. Thus, they provide little insight into the variety of ways a diverse range of Christians might be better supported in their work by churches and clergy. |

| 4 | All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board (Project identification code). |

| 5 | Gallup drew a stratified sample of 29,345 individuals, aiming to match U.S. population targets based on the 2017 Current Population Survey, as well as oversamples of pre-identified Muslim (n = 752) and Jewish (n = 882) respondents, yielding a participation rate of 45.2 percent and a response rate—which accounts for all stages of recruitment per AAPOR—of 1.2 percent. We knew that a probability-based panel would include a large number of Christians, but we chose to include oversamples of Muslims and Jews in the sample selection in order to accurately characterize faith–work integration and religious discrimination among members of these minority religious traditions, as well as to compare members of minority religious traditions to the Christians in our sample. |

| 6 | 154 interviews with Christians. In a second stage, we identified Muslim and Jewish survey takers and recruited them to participate in an interview as a comparison group. |

| 7 | ST44, Man, Caucasian, 31, Maintenance Technician, South Carolina, Evangelical. |

| 8 | ST07, Woman, White, 49, Senior Communications Specialist (Univ IT), California, Episcopal. |

| 9 | ST07, Woman, White, 49, Senior Communications Specialist (Univ IT), California, Episcopal. |

| 10 | ST85: Man, Asian American (Vietnamese), 22, Graduate Student, Missouri, Catholic. |

| 11 | ST83, Man, African, 20, IT Tech Support, Maryland, Anglican. |

| 12 | ST85, Man, Asian American (Vietnamese), 22, Graduate Student, Missouri, Catholic. |

| 13 | ST104, Woman, White, 31, Director of Marketing, Kentucky, Evangelical. |

| 14 | ST76, Woman, Hispanic/White, 67, Call Center Worker, New Hampshire, Roman Catholic; ST62, Man, White, 59, Transportation Consultant, Florida, Catholic. |

| 15 | ST97, Woman, White, 29, College Recruiter, Alabama, Methodist. |

| 16 | ST100, Man, Hispanic/Caucasian, 65, Delivery Driver, California, Baptist. |

| 17 | ST35, Man, White, 64, Business Owner, Nevada, Lutheran. |

| 18 | ST39, Woman, White, 29, Engineer, Virginia, Evangelical. |

| 19 | ST65: Woman, Alaskan Native, 35, Small Business Owner, Ohio, Evangelical. |

| 20 | ST47, Woman, African American/Native American, 63, Executive Director, Pennsylvania, Episcopalian; ST03, Woman, White, 50, Income Tax Preparer, Massachusetts, Roman Catholic; ST28, Woman, Caucasian, 56, Kindergarten Teacher, Texas, Evangelical; ST22, Woman, White, 46, Teacher, Alabama, Evangelical; ST21, Woman, White, 25, Spanish Teacher, Illinois, Evangelical; ST75: Man, White, 69, Reliability and Quality Engineer, Iowa, Evangelical; ST70, Man, White, 54, Maintenance, Maryland, Methodist; ST94; Man, White, 28, IT Health Desk Technician, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 21 | ST46, Man, White/Hispanic, 57, Consultant Manager, New York, Evangelical. |

| 22 | ST47, Woman, African American/Native American, 63, Executive Director, Pennsylvania, Episcopalian. |

| 23 | ST21, Woman, White, 25, Spanish Teacher, Illinois, Evangelical. |

| 24 | ST88, Woman, Black, 45, Human Resources, Texas, Baptist. |

| 25 | ST12, Man, Hispanic, 33, External Communication Manager, Florida, Evangelical. |

| 26 | ST103, Woman, White, 57, Teacher/Librarian, California, Episcopalian; ST96, Man, White, 50, Actuary, Indiana, Evangelical; ST87, Man, White, 35, Farmer, Oklahoma, Evangelical; ST81, Man, African American, 69, Concierge, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 27 | ST96, Man, Caucasian, 50, Actuary, Indiana, Evangelical. |

| 28 | ST25, Man, Hispanic (non-White), 36, Asset Manager, Dept of Corrections, California, Catholic. |

| 29 | ST40, Man, White, 42, Paramedic Supervisor, Oregon, Evangelical; ST45, Woman, White,48, Tutor, Connecticut, Evangelical; ST56, Woman, Asian, 35, Pediatrician, California, Mainline; ST77, Woman, White, 22, Data Analyst, Virginia, Evangelical; ST37, Man, White/Hispanic, 43, High School ROTC Instructor, Pennsylvania, Evangelical. |

| 30 | ST49, Man, Black, 38, Criminal Investigator, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 31 | ST31, Woman, White, 25, Civil Engineer, Washington, Evangelical; ST36, Woman, White, 45, Associate Professor, Ohio, Catholic. |

| 32 | ST102, Woman, Black (British), 32, Assistant Professor, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 33 | ST29, Woman, White, 55, Law Enforcement Deputy, Colorado, Lutheran. |

| 34 | ST54, Woman, White, 36, Nurse Practitioner, Indiana, Evangelical. |

| 35 | ST98, Woman, Caucasian, 60, Nurse, Minnesota, Evangelical. |

| 36 | ST19, Woman, White, 55, Spanish Teacher, Ohio, Evangelical. |

| 37 | Man, White, 49, CFO, California; Evangelical; ST15, Woman, White, 47, Financial Services, Arizona, Evangelical; ST66, Woman, African American, 50, Tech Consultant, Virginia, Evangelical; ST73, Man, Black, 31, Human Resources, Michigan, Evangelical. |

| 38 | ST24, Man, White, 31, Land Surveyor, Maine, Conservative Baptist. |

| 39 | ST42, Woman, White, 31, Art Teacher, Illinois, Roman Catholic. |

| 40 | ST72, Man, White, 23, Engineer, Pennsylvania, Catholic. |

| 41 | ST13, Man, Filipino, 32, Politician, California, Evangelical. |

| 42 | ST86, Woman, White, 21, Nurse, Tennessee, Evangelical. |

| 43 | ST16: Male, White, 32, Engineering Consulting, Nebraska, Lutheran. |

| 44 | ST17, Woman, Black, 40, Corporate Trainer, Georgia, Evangelical. |

| 45 | ST71, Woman, African American, 66, Reimbursement Analyst, California, Evangelical. |

| 46 | ST58, Man, White, Director of Field Operations, California, Evangelical. |

| 47 | ST41, Woman, Caucasian, 60, Accountant, Nebraska, Evangelical. |

| 48 | ST61, Man, White, 43, Manager, Minnesota, Catholic. |

| 49 | ST55, Woman, 39, Mixed (Caucasian, Cuban), Substitute Teacher, North Dakota, Evangelical. |

| 50 | ST17, Woman, Black, 40, Corporate Trainer, Georgia, Evangelical. |

| 51 | ST60, Woman, Caucasian, 53, Wedding Coordinator, Pennsylvania, Evangelical. |

| 52 | ST09, Man, African American, 50, Program Manager, Illinois, Evangelical. |

| 53 | ST33, Man, White, 48, Business Owner, Wisconsin, Evangelical. |

| 54 | ST43, Man, Black, 48, Graphic Artist, Florida, Presbyterian. |

| 55 | ST20, Man, White, 50, Engineering Manager, Michigan, Catholic; ST30, Woman, Black (Hispanic), 47, Senior Analyst, Georgia, Evangelical; ST101, Woman, White, 73, Educational Consultant, Massachusetts, Catholic |

| 56 | ST21, Man, White, 32, Land Assistant, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 57 | ST38, Woman, Hispanic, 51, Finance, Texas, Evangelical. |

| 58 | T57, Woman, African American, 59, Executive Director of Non-Profit, North Carolina, Evangelical. |

| 59 | ST37, Man, White/Hispanic, 43, ROTC Instructor, Pennsylvania, Evangelical. |

| 60 | ST18, Woman, African American, 45, Financial Analyst, Tennessee, Evangelical. |

| 61 | ST01, Woman, White, 50, Office Manager/Business Owner, Tennessee, Evangelical. |

| Demographic Variables | Percent * |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Man | 46.0 |

| Woman | 53.2 |

| Prefer to self-describe | 0.3 |

| Prefer not to say | 0.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 65.3 |

| Black | 13.8 |

| Asian | 0.4 |

| Hispanic | 12.1 |

| Other | 0.7 |

| Multiracial | 7.7 |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 4.2 |

| 25–34 | 18.7 |

| 35–44 | 15.2 |

| 45–54 | 19.7 |

| 55–64 | 18.8 |

| 65+ | 23.4 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 46.0 |

| Some Tech/Trade/College | 20.4 |

| 2-year associate degree | 7.0 |

| 4-year bachelor’s degree | 11.2 |

| Post-graduate school/degree | 15.4 |

| Income | |

| $35,999 or less | 23.7 |

| $36,000 to $59,999 | 19.1 |

| $60,000 to $119,999 | 35.8 |

| $120,000 or more | 21.4 |

| Religious Identity | |

| Catholic | 27.7 |

| Evangelical | 27.9 |

| Mainline | 13.6 |

| Other Protestant/Christian | 30.8 |

| Church Attendance | |

| Several times per year or less | 42.7 |

| 1–3 times per month | 12.8 |

| Nearly every week/every week | 34.5 |

| Multiple times per week | 10.0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howard Ecklund, E.; Daniels, D.; Schneider, R.C. From Secular to Sacred: Bringing Work to Church. Religions 2020, 11, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090442

Howard Ecklund E, Daniels D, Schneider RC. From Secular to Sacred: Bringing Work to Church. Religions. 2020; 11(9):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090442

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoward Ecklund, Elaine, Denise Daniels, and Rachel C. Schneider. 2020. "From Secular to Sacred: Bringing Work to Church" Religions 11, no. 9: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090442

APA StyleHoward Ecklund, E., Daniels, D., & Schneider, R. C. (2020). From Secular to Sacred: Bringing Work to Church. Religions, 11(9), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090442