Abstract

The final 15 folios of the Nepalese illuminated palm-leaf manuscript of the Sanskrit Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra of c. 1100 have more paintings per page, larger picture planes, and different types of scenes than are found on the leaves surviving from the first 340 folios. One example is Folio 348 in the Cleveland Museum of Art, which has been painted with scenes of a bodhisattva tossing a blue-skinned heretic, an unusual image of a monk or upāsika wearing blue robes, and a Vajrācārya priest setting a Hindu rishi ablaze. From the point of view of the Mahāyāna Buddhist makers of this manuscript, these figures may personify the wrong views that derail pilgrims on the bodhisattva path to enlightenment. The dramatic shift in imagery appears to reflect the transition from the end of the inspirational pilgrimage of Sudhana to the popular, protective dhāraṇī verses of the Bhadracarī that form the finale to the text. The scenes of destruction and elimination of heretical figures correspond with sentiments in the Bhadracarī, indicating that the artists understood the structure and content of the text.

Among the 185 published folios1 from the only known illuminated Sanskrit manuscript of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array),2 one leaf, Folio 348 in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art (1955.49.7), stands out from the others for its unusually dramatic imagery. Unlike most of the folios, which have only one approximately square painting at the center of the recto, Folio 348 has six paintings, three on the recto and three on the verso, and two are of such singular subjects that they may imply more understanding of the content and structure of the text on the part of the artists than has been previously recognized. The verso is here being published in its entirety in color for the first time, which may explain why scholars have not analyzed its paintings thus far.3

The manuscript from which the Cleveland leaf has come is attributed to Nepal in the late eleventh to early twelfth century on the basis of style,4 because its colophon does not contain a date.5 Ever since it came to light during the 1950s, its paintings have been lauded for their lyricism and visual appeal. Milo Cleveland Beach wrote in 1966 (Beach 1966, p. 105): “Whatever the subject matter, the illuminations betray a unique style, characterized by animated vigor and languorous grace and a mastery in the drawing and delineation of the form.” More recently, in 2019, Jinah Kim described them as follows (Lewis and Kim 2019, p. 91):

The Nepalese paintings of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra remain widely admired as some of the finest examples of early Buddhist manuscript illumination with close ties to the art of eastern India and stylistic elements that recall paintings made at least seven centuries prior, as known from the murals at Ajanta.Whether a single figure like the princely figure (perhaps the model lay pilgrim of the text, Sudhana) standing alone in the forest or multiple figures engaged in conversation, the paintings in the Gaṇḍavyūha manuscript convey such a vivid sense of animation and emotional charge so that each painted scene dominates the whole page; these masterpieces do so despite their diminutive size, only occupying less than one tenth of the space of the entire page.

The manuscript’s Sanskrit text is rather loosely handwritten in an informal version of the northern Indian script called rañjanā. The lines of text continue from the left end of the leaf to the right across spaces for binding holes and paintings, and the folio number has been hastily noted in numerals of the type used in medieval Nepal on the verso of each leaf, in the space above the left binding hole.

At present, to my knowledge, 185 folios out of a total of 355 are accounted for, and others may be identified in the future. Among the 185 known folios, 140 have illuminations—a large percentage. If the remaining 170 folios that have not been documented are all text-only folios, at a minimum, about 40% of the folios include paintings, which constitutes a significant investment of time and cost. Eva Allinger assiduously located and compiled 38 of the folios dispersed among private collections and museums (Allinger 2008),6 and those all appear to be traceable to the Heeramaneck collection; to her list, four folios in the Harvard Art Museums, also from Heeramaneck, are to be added.7 In 2013, Alexey Vigasin published his observations on the 144 folios plus the covers of the manuscript that Svyatoslav Roerich (1904–1993), the artist, collector, and son of the Russian artist Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) and theosophist Helena Roerich (1879–1955), had obtained in India during the 1950s (Vigasin 2013, p. 256). The illuminated pages and the text pages were catalogued under two accession numbers (No. 471 and No. 472, respectively) in the collection of the International Centre of the Roerichs Museum, named after Nicholas Roerich, in Moscow from 1990 until 2017, and they are now held in the State Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow. Vigasin has listed the folio numbers of all the Moscow pages together with the 38 compiled by Allinger, and he noted whether or not they are illuminated with the number of paintings per folio (Vigasin 2013, pp. 257–58). Most of the pages from the beginning and the end of the manuscript have survived. Missing folios are scattered throughout the entire manuscript, and as yet, too many paintings remain unpublished, and too many folios remain undocumented to allow precise conclusions to be drawn regarding patterns or placement of imagery throughout the manuscript.

Broadly speaking, it seems tentatively certain that the imagery is fairly consistent until about the last 15 folios. Up to Folio 340, all the paintings are located only at the center of the recto; even the few pages that have two paintings on one folio appear to include both scenes within the central space of the recto separated by only a vertical line.8 Furthermore, the subjects of the paintings up to Folio 340 appear to be variations on the theme of either an individual in a wild landscape or an interlocution between a disciple who is presumably the pilgrim Sudhana and a kalyāṇamitra (True Friend). From one painting to the next, the appearance of the pilgrim-disciple varies, with different skin tones, hair styles, and garments and the inconsistent portrayal of a halo, though he is always a well-dressed layperson. The variation of details seems to imply that the pilgrim-disciple can be interchangeable, that there is not just one Sudhana: there have been and will be potentially many or even infinite Sudhanas, which suggests that any one of us can follow his path.

After Folio 340, however, until the end of the manuscript, there are paintings that depict entirely different kinds of scenes. Vigasin concluded the following (Vigasin 2013, p. 262):

It is interesting to note something else: it seems that a number of miniatures from the final part of the manuscript come from another artist. Along with variations of the preceding scenes (Sudhana’s wanderings or his apprenticeship) appear new ones: a group of monks or some fantastic creatures with horse, snake or bird heads (kinnaras, garuḍas, nāgas, or mahoragas?) These images deserve further discussion.

A crowded assembly of monks with offerings fills a long rectangular panel in the center of the recto of Folio 341 (Vigasin 2013, p. 263), and Folio 344 is the earliest among the known folios of this manuscript to have three paintings appear on one page. In the center of the recto of the last folio is a scene of four monks venerating a stūpa (Vigasin 2013, p. 255). Whether or not a different artist painted the scenes on the last fifteen folios can only be determined by further analysis of the surviving folios, which is not feasible with the images currently available, but, at least, it seems evident that a change in visual effect was intentionally implemented at the end of the manuscript. Folio 348 in the Cleveland Museum of Art is the only page from this last section for which there is open-access high-resolution photography, and the quality of the paintings accords with those of the earlier folios, suggesting that they were not added or interpolated much later; they are part of the original conception of the manuscript as a whole.

Folio 348 is one of the seven folios the Cleveland Museum of Art purchased from the Heeramaneck Galleries on March 10, 1955 (1955.49.1–7). The text on this leaf—a translation of which, by Douglas Osto, is reproduced in Appendix A—falls approximately midway through the last chapter, Chapter 55, called the Ārya-Samantabhadra-caryā-praṇidhāna-rāja (Royal Vow to Follow the Noble Course of Conduct of Samantabhadra), which consists of two parts: a prose section followed by a concluding verse section. The section of the text on this folio is from close to the end of the prose section,9 and Folio 348 is probably the fourth from the last leaf before the beginning of the verses, which form the remainder of the chapter—indeed the coda of the entire manuscript. There are 62 verses in all, and they form a coherent dhāraṇī, or ritually powerful spell, called the Bhadracarīpraṇidhānam (Vow to Follow the Good Course of Conduct), which in itself, independent of the Gaṇḍavyūha, was widely popular throughout the Mahāyāna Buddhist world.10 By the 8th century, the Bhadracarī was incorporated into the Gaṇḍavyūha as its conclusion in the Sanskrit and Tibetan versions of the text.11 In Nepal, in particular, the verses are widely known and recited regularly (Gellner 1992, p. 107), and the paintings on the verso of Folio 348 seem to indicate the artist’s awareness of the content of the Bhadracarī. The six paintings on this folio form part of a vigorous visual finale to the first 340 pages of the manuscript, which constitute a patient pilgrimage from one kalyāṇamitra to another, with each solitary painting showing a single figure in a landscape or interacting with a teacher. The double-sided multiple paintings on Folio 348, along with the changes in subject matter and an increase in the number of paintings per folio spanning the last 15 leaves, signal a shift in visual intent that seems to mirror the change in the text from the end of the Gaṇḍavyūha proper to the beginning of the talismanic Bhadracarī verses.

The paintings on the recto of Folio 348 depict the great bodhisattvas of wisdom and compassion: Mañjuśrī and Avalokiteśvara (Figure 1). The central painting is relatively large, measuring 4.8 × 9.7 cm at its maximum extents. Mañjuśrī, with golden skin, sits in majesty on a lotus pedestal in lalitāsana, with a yoga bandha tied around the right knee, a yajñopavīta or sacred thread of a twice-born prince or priest over the left shoulder, and a full complement of jewelry (Figure 2). The attribute that identifies him as Mañjuśrī, the blue lotus (technically a lily, or utpāla) supporting a book, is by his left shoulder, blossoming at the top of a curving green stem. His form is set off against a circular mandorla of red flames with golden tongues flickering across the field and around its periphery. His hands are held in the gesture of teaching, the dharmacakramudrā, and two figures, one of which may well be the pilgrim Sudhana, kneel on either side with their hands in añjalīmudrā. The background is painted a watery ultramarine, shaded more darkly around the edges as is characteristic of this manuscript’s painting style.

Figure 1.

Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī with Two Forms of Avalokiteśvara, Folio 348 recto from a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1100, Nepal, gum tempera and ink on palm leaf; average: 4.2 × 52.4 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1955.49.7.a.

Figure 2.

Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī with Worshippers, detail of Figure 1.

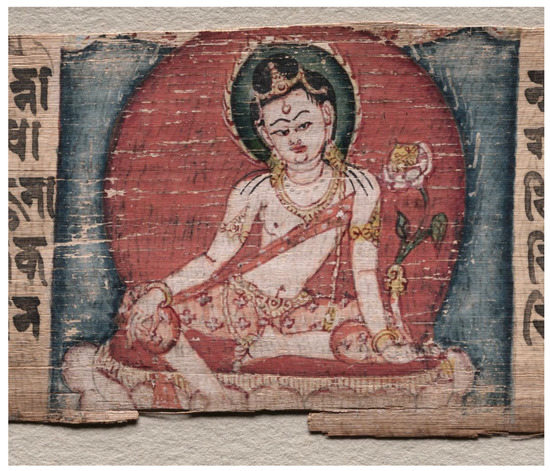

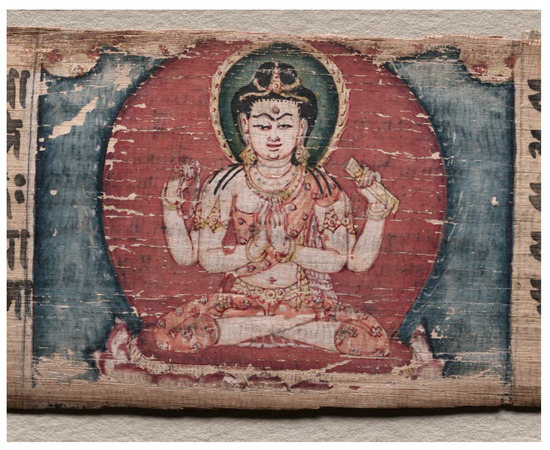

On the viewer’s left side of the recto, in a smaller squarer picture plane measuring 4.5 × 5.1 cm, is Avalokiteśvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion, with white skin, seated on a lotus pedestal in lalitāsana, also with a yoga bandha supporting the right knee and a yajñopavīta; he holds a lotus flower in his left hand (Figure 3). On the viewer’s right side is another squarish painting (4.8 × 6.2 cm) depicting Avalokiteśvara, white in color on a lotus pedestal (Figure 4). In this depiction, the bodhisattva is seated in padmāsana and has four arms; his lower two hands are in añjalīmudrā, and the upper hands hold a rosary and a book. Textile swags drape across the top edges of all three paintings, as a sign of honor shown to the exalted figures. These three paintings proclaiming the splendor of the bodhisattvas of wisdom and compassion would seem to be a fitting visual conclusion to the pilgrimage text. They emphasize the presence of the enlightened beings at the end of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra and foreground the central role of Mañjuśrī in the text.12 Visually, their iconic, frontal portrayals contrast to the three-quarter views and more natural postures of the kalyāṇamitras and the pilgrim Sudhana painted on the previous folios.

Figure 3.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, detail of Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Four-Armed Avalokiteśvara, detail of Figure 1.

The central position of Mañjuśrī on the recto may also announce the Bhadracarī, which explicitly states that it is Mañjuśrī’s vow, even though it is spoken by Samantabhadra (Osto 2010, p. 16):

May I undertake Mañjuśrī’s vow

Regarding the universally beneficial Bhadracarī

May I fulfill all undertakings without remainder

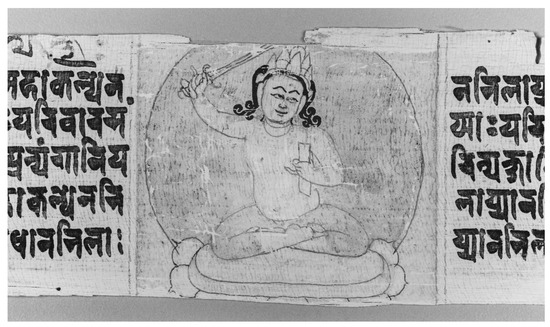

The verso of Folio 348 (Figure 5) has, on the left, an image of bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, who appears this time as an onlooker, rather than a central icon (Figure 6). Clutching a book in his left hand, he holds up his sword as though ready to support the action in the two adjacent scenes to which he directs his gaze. These elements are clearly discernible in the infrared photograph that shows the drawing under the pigment (Figure 7). He sits in the full lotus posture of yogic attainment, and the end of his upper garment flutters dramatically up in the air next to him, implying a turmoil or intense wind sourced from either his own energy or the drama of the central scene. His body is not lithe as it is on the recto; instead, it is portly and powerful, reminiscent of the figure of a lokapāla, or guardian king. The sword-bearing lokapāla Virūḍhaka from a Pañcarakṣā manuscript produced in the 14th year of Nayapāla (c. 1057 CE) in the Cambridge University Library (Add.1688) has a similar bodily form (Figure 8).Unwearied for all future eons. (44)

Figure 5.

Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī and the Elimination of Heretics, Folio 348 verso from a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1100, Nepal, gum tempera and ink on palm leaf; average: 4.2 × 52.4 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1955.49.7.b.

Figure 6.

Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, detail of Figure 5.

Figure 7.

Infrared photograph of Figure 6.

Figure 8.

Lokapāla Virūḍhaka, detail of Folio 45 verso of a Pañcarakṣā (Five Protections), 14th year of Nayapāla (c. 1057 CE), India. Copyright Cambridge University Library (Add.1688), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC 3.0).

Virūḍhaka is a protector, and casting Mañjuśrī in the form of a protector visually amplifies the function of the Bhadracarī as a protective dhāraṇī at the end of the manuscript. As Osto stated (Osto 2010, p. 7), “… the union of the Gaṇḍavyūha and the Bhadracarī is a marriage of an inspirational text to a liturgical text.” The Bhadracarī, as a powerful spell, was to be recited in ritual contexts, for protection, and the text explicitly states what it protects from and what it provides (Osto 2010, pp. 17–18):

- Possessing this Bhadracaripraṇidhānam,

- One abandons evil states of existence and bad friends,

- And quickly sees Amitābha. (49)

- For such ones profit and a happy life are easily obtained.

- They duly arrive at this human birth;

- Before long they even become like Samantabhadra. (50)

- Whoever has committed through the power of ignorance

- The heinous five deadly sins,

- Reciting this good course,

- He quickly brings [this evil] entirely to its destruction. (51)

- He will be endowed with knowledge, beauty,

- The characteristic marks [of a superior person],

- A good social class and clan.

- He will be unassailable by the hosts of heretics and māras,

- And be worshipped in all three worlds. (52)

- Quickly he goes to the best tree of enlightenment.

- Having gone there, he sits for the benefit of beings.

- Awakening to enlightenment, he would turn the wheel [of Dharma], and

- Overcome Māra and his entire army. (53)

- Whoever henceforth would maintain, recite or teach

- This Bhadracaripraṇidhānam,

- [for such a one] the Buddha knows the spiritual maturation arising from this.

- You should not beget doubt regarding this most excellent enlightenment. (54)

- As the hero Mañjuśrī knows,

- Just so also does Samantabhadra.

- Imitating them, I will direct

- This merit toward all. (55)

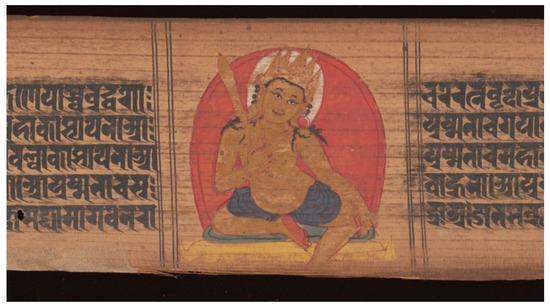

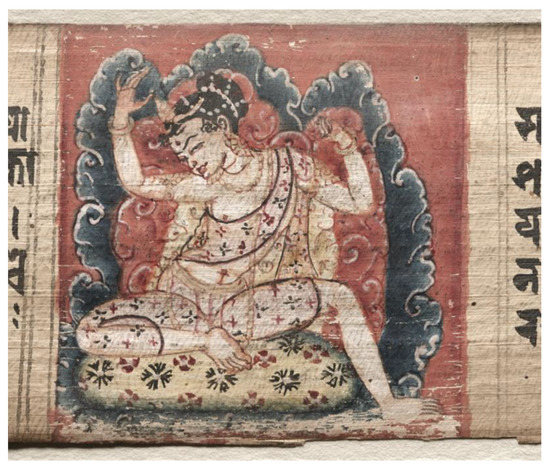

The central scene is set against a dramatic vermillion13 ground and features a bodhisattva figure with a furrowed brow and eyes popping in anger (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Standing in mid-action, up on his toes with knees bent, he grasps a blue-skinned figure by the shoulder and one thigh and appears to be in the act of tossing him away. The end of his upper garment flutters up behind him in response to the effort. The blue14 figure looks startled and frightened, with his mouth open and teeth bared; both hands touch the ground, and both feet are in the air in a posture of helpless defeat. He wears a very diaphanous lower garment through which male genitals are discernible.

Figure 9.

Bodhisattva Tossing a Tīrthika, detail of Figure 5.

Figure 10.

Infrared photograph of Figure 9.

The heroic figure in the act of tossing the blue-skinned enemy shares many similarities with the figures of Mañjuśrī and Avalokiteśvara on the recto and on the left of the verso of this same leaf. They all wear the same sacred thread of a twice-born person in alternating red and white and have a similar pectoral and bracelets; he has long locks flowing over his shoulders, similar to Avalokiteśvara, but a golden skin tone similar to Mañjuśrī. That he is a bodhisattva seems clear, but whether he is Samantabhadra or Mañjuśrī is not certain, given the absence of any other attribute. Perhaps this bodhisattva stands for the Bhadracarī itself, which means, literally, “good course of conduct”, explained by Osto (Osto 2010, p. 9, note 35) as the “… course of conduct of the bodhisattva, which leads to the eventual attainment of awakening. There is often ambiguity in the verses with regard to the term bhadracarī as to whether it refers to the practice of the Good Course, or the text itself. This ambiguity may be intentional.” The iconographic ambiguity of this bodhisattva may have been intentional, as well, standing in for the text and the good course of conduct, like the goddess Prajñāpāramitā, who personifies both the book and its contents.

Similar to the blue-skinned demonic being that is attacked and driven away by a krodha, a fierce dharma protector (Figure 11), in the Pañcarakṣā manuscript of Year 39 of Rāmapāla (1117 CE),15 this blue-skinned figure being tossed may stand for an obstacle on the good course to enlightenment. The nakedness of the figure also implies heresy, in a Buddhist context, so the form of an obstacle on the path to enlightenment is here given the appearance of a heretic.16 Recitation of the Bhadracarī, after all, does result in being unassailable by heretics, according to verse 52, quoted above.

Figure 11.

Krodha Attacking a Demonic Figure, detail of Folio 64 recto of a Pañcarakṣā (Five Protections), 39th year of Rāmapāla (c. 1117 CE), India, Cleveland Museum of Art, promised gift from the Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Ralph Benkaim Collection 16.2014.

Another kind of heretic may be recognized in the image of a kneeling male figure clad in blue17 monastic robes with a white18 lower garment—a combination not found among orthodox Buddhist sects from a Nepalese Mahāyāna or Vajrayāna perspective (Figure 9). A painting of an enlightened Buddhist monk, a kalyāṇamitra from Folio 125 of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra manuscript wears a red robe, as would be expected (Figure 12), so the artist has created a clear distinction between an exemplary kāṣāya-clad monk, being honored by a kneeling nimbate Sudhana, and a deviant, heretical nīlapaṭadhara monk who wears blue.

Figure 12.

Sudhana and a Monk, detail of Folio 125 recto of a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1100, Nepal, gum tempera and ink on palm leaf; Private Collection.

The hair of the blue-clad figure is close-cropped in a tonsure, but he wears a diadem, earrings, and a necklace, like a lay follower (upāsaka). He holds a white stem—in contrast to the lovely green stem of the lotus of Avalokiteśvara on the recto—topped with an odd foliate element on which rests a skull cup or bowl from which issues curls of steam or smoke. This attribute is unfamiliar among Indian, Nepalese, or Tibetan ritual objects. Just as the garb is not mainstream, neither is the attribute. Little is known about the blue-clad sect of monks, but they appear to have been radical heretics who practiced extreme forms of tantra.19 A Sri Lankan historical chronical, the Nikāyasaṅgraha, includes a narrative about blue-clad monks during the time of king Harsha (590–647) in southern India (Deegalle 2004, p. 53):

At that time, an ‘impious’ Sammitiya monk, wearing a blue robe, visited a harlot at night; after spending the night there, he returned [to the] vihāra at daybreak. According to the Nikāyasaṅgraha, when his pupils questioned him whether his blue robes were appropriate for Buddhist monks, he praised their appropriateness. From then on, his devoted followers also began wearing blue robes rejecting the traditional saffron robes of the Buddhist monk. To that radical monk, the Nikāyasaṅgraha, attributes the authorship of the alleged Nīlapaṭadarśana text. This Indian teacher of the ‘philosophy of blue robe’ outlined the nīlapaṭadarśana despising the traditional three jewels as mere crystal stones and replacing them with (a) prostitutes, (b) liquor and (c) love. These two verses not only suggest a religious opinion contrary to Theravāda precept and practice, by replacing the traditional notion of the three jewels, they also challenge the entire soteriological system of Theravāda.

Though the text from Sri Lanka is not directly relevant to the Mahāyāna or Vajrayāna milieu of the Gaṇḍavyūha–sutra in Nepal, it may provide some clues as to the practices of and attitudes towards blue-clad practitioners that are borne out in the painting. The kneeling blue-clad figure is likely to be the next to be tossed in the bodhisattva’s purification of the course to enlightenment, as an example of one who abides in an “evil state of existence” or a “bad friend” who is to be abandoned.

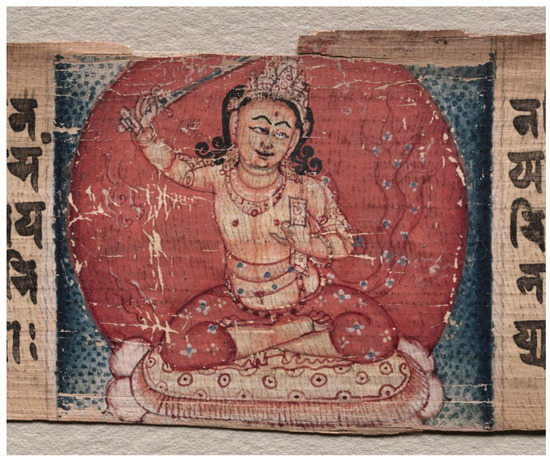

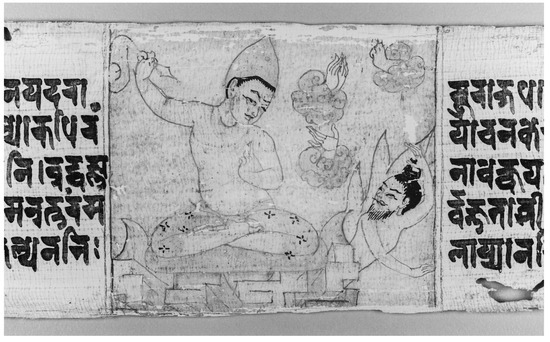

The painting on the right of the verso of Folio 348 is no less dramatic. A figure seated on a rocky mountain in padmāsana, wearing the yajñopavīta and princely jewels, similar to the bodhisattvas, wears a conical red headdress of a Vajrācārya priest (Figure 13).20 Claudine Bautze-Picron noted that the Tibetan historian Tāranātha (1575–1634) recorded that during the Pāla and Sena periods (8th to 13th century) in India, all Mahāyāna paṇḍits wore pointed caps. He relates the origin (Bautze-Picron 1995, p. 62):

This figure, then, is wearing the headgear of one who debates with and is victorious over a theological opponent. He directs his gaze down to a figure of a burning rishi, and with his left hand, he holds up his index finger in the threatening tarjanimudrā. In his raised right hand, he holds an object that changed from the underdrawn version, which showed a pointed dagger in the infrared photograph (Figure 14), to a vajra-like handle of a cloudlike whisk.A number of tīrthika debators announced that they were going to have a debate there on the following morning. The monks felt uncertain about their own capacity. An old woman turned up at that time and said, ‘While having the debate, put on caps with pointed tops like horns. And this will bring you victory.’ They acted accordingly and won victory. In other places also, they became victorious in a similar way. From then on, the paṇḍitas adopted the practice of wearing pointed caps.

Figure 13.

Vajrācārya Smiting a Rishi, detail of Figure 5.

Figure 14.

Infrared photograph of Figure 13.

He also has the stocky build of a protector, and his location on a rocky mountain recalls early tantric depictions of Vajrapāṇi, a wrathful protector of the Dharma.21 This priest figure visually serves as a counterpart to the Mañjuśrī on the opposite side of the leaf; they are in nearly identical poses. Phyllis Granoff located a stotra to Mañjuśrī that identifies him as one who burns up false beliefs according to the Nepalese Svayambhūpurāṇa.22 In this painting, the personification of a false belief has the appearance of a Brahmanical rishi. He has a beard, white skin, and long, matted locks piled up on his head, similar to the rishi who is an enlightened kalyāṇamitra from Folio 94 (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Sudhana and the Rishi Bhiṣmottaranirgoṣa, detail of Folio 94 recto of a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1100, Nepal, gum tempera and ink on palm leaf; average: 4.2 × 52.4 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1955.49.2.a.

The paintings in this manuscript, therefore, communicate that some rishis—like some monks—are enlightened and worthy of veneration, but others are the opposite and must be recognized as carriers of false beliefs. As another verse from the Bhadracarī states (Osto 2010, pp. 12–13):

May the beautiful mind aimed at enlightenment

Intent upon the perfections never be confused.

And what evil obstructions there might be,

The Bhadracarī contains numerous such instances of strong language evoking the destruction of obstacles on the path of good conduct. These sentiments relate to the aggressive and violent imagery on the verso of Folio 348, and they contrast markedly to the consistently gentle and reverent aspect of all the paintings from the first 340 folios of this manuscript of the Gaṇḍavyūha. In the painting on the right side of Folio 348, the red-capped Vajrācārya priest, just as Mañjuśrī burns up false beliefs, threatens and destroys by fire the figure of a Brahmanical rishi, thereby clearing Hindus off the path to enlightenment. The bodhisattva in the central painting takes on other kinds of heretics, the nīlapaṭadhara Sammitiya monk and the genital-revealing blue-skinned tīrthika, both of whom, similar to the rishi, are propounders of confused or incorrect ideologies that would create obstructions and deviations from the good course of conduct.Let them entirely be destroyed. (19)

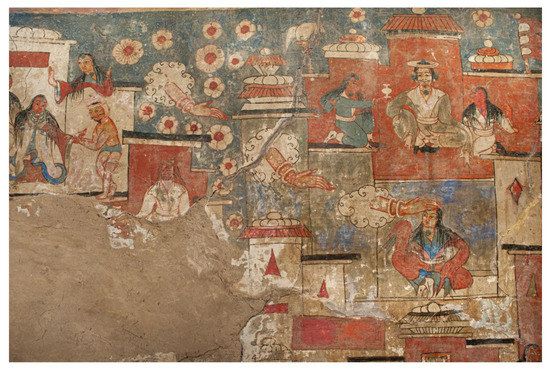

In the sky above the burning rishi are three red clouds from which hands emerge. One is gesturing with the palm out; one is a pair of hands in añjalīmudra, and one appears to be in tarjanimudrā. Similar cloud hands, which Phyllis Granoff recognizes as a literal visual translation of the Sanskrit pāṇimegha, meaning “multitude of hands”, are painted in the eleventh-century murals of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra in the assembly hall of the monastery of Tabo in the western Himalayan region of Lahul and Spiti (Figure 16). There, a Tibetan inscription identifies the hands as those of Mañjuśrī (Steinkellner 1995, p. 103): “Sudhana goes to Sumanāmukha and stays there thinking about and wishing to meet Mañjuśrī. Mañjuśrī extends his hand ‘over a hundred and ten leagues’ and lays it on Sudhana’s head.” The cloud hands of Mañjuśrī at Tabo are so distinctive and similar to those on the verso of Folio 348 that they indicate a shared visual vocabulary between the mural artists illustrating the Tibetan translation of the Gaṇḍavyūha in the western Himalayas and Nepalese painters illuminating the Sanskrit version in Nepal. It is possible that the cloud hands of Folio 348 are intended to be the hands of Mañjuśrī as well, and it is he who is burning up false beliefs in the form of the rishi, as the Vajrācārya looks on or possibly even invokes the power of Mañjuśrī.

Figure 16.

Mañjuśrī Extends his Hand and Lays It on Sudhana’s Head, from a mural of the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1047, Tabo Monastery, Lahul and Spiti, India. Photo by L. Fieni, 2010.

These clouds of hands are part of the rishi-smiting scene that resonates with the content of the Bhadracarī, but they also are a link to the climax of the prose section of Chapter 55. Just before the start of the text on the recto of Folio 348, on what would have been the verso of Folio 347, is a vivid description of clouds of hands put forth by the bodies of the bodhisattva Samantabhadra that touched the head of Sudhana and caused him to realize “entrances into the Dharma” (Osto 2013, p. 15). As a literal visual translation of the Sanskrit pāṇimegha, or “clouds of hands”, which means a “multitude of hands”, the image of hands appearing in clouds suggests the artist’s familiarity with the words of the text,23 as the neutral pluralizer—megha (clouds of )—occurs no fewer than 40 times within the prose section of the Ārya-Samantabhadra-caryā-praṇidhāna-rāja alone, but not at all in the verses of the Bhadracarī.

The six paintings on Folio 348 have no clear or direct connection with the actual text that is written on the folio itself. This is the case with most of the paintings from this manuscript, as Eva Allinger has observed (Allinger 2008). Several of the paintings are specific to content of the text but are located at some remove from the related text in the manuscript and have nothing to do with the text on the same leaf. Allinger noted specifically that the scene with the rishi Bhiṣmottaranirgoṣa on Folio 94 (Figure 15), who is identifiable by the banner behind him that indicates the name of his “undefeated banner” form of liberation, and who lays his hand on Sudhana’s head to transmit the teaching, closely follows textual content from Chapter 11, while the text on Folio 94 itself is from the end of Chapter 16. Still, it would seem that the artists were familiar with the text, even though, for some reason, the paintings for the most part do not occur together with their associated text. One exception may be Folio 22 in the Cleveland Museum of Art, in which a bodhisattva sits on a cushion with the left leg pendant in an active pose, arms raised, surrounded by clouds of three colors (Figure 17). On the same folio in the text is invoked “many clouds of bodhisattvas” and Samantabhadra who “spins clouds of things”.24

Figure 17.

Samantabhadra Spinning Clouds of Things, detail of Folio 22 recto of a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Scripture of the Supreme Array), c. 1100, Nepal, gum tempera and ink on palm leaf; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1955.49.6.a.

The clouds of hands on the verso of Folio 348 are part of the climax of the last chapter—and arguably of the entire Gaṇḍavyūha—appearing in the lines of text immediately preceding Folio 348, suggesting some possible awareness or intended visual connection to the scene. Furthermore, the tableau on the recto with the three images of the bodhisattvas in majesty function similar to a finale, the soteriological goal of the text, and it seems fitting to find those kinds of paintings at the end of the text. That the central figure is Mañjuśrī and not Samantabhadra is noteworthy, but in the absence of other adjacent folios that may have featured Samantabhadra, no conclusion can be drawn as to the reason. The turn toward aggressive and protective imagery on the verso foreshadows the function of the upcoming dhāraṇī that closes the text, here featuring the eschewing and destruction of figures thought to harbor the wrong views. It is possible that subsequent folios, the present whereabouts of which are not currently known, also had images pertaining to the content of the popular Bhadracarī, and the artist need not have been able to read the text, because it was frequently recited and well known. Were the manuscript complete, or at least if the Moscow folios could be available for study, the internal logic and further clues regarding the relationship between this influential text and its sublime images would undoubtedly become apparent.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks go first and foremost to Phyllis Granoff for her encouragement in embarking on this challenging topic of research and her constant help along the way with navigating the text, finding references and generating accurate translations and interpretations. I also must thank Eva Allinger, Catherine Glynn Benkaim, Amy Heller, Chiyo Ishikawa, Alexey Vigasin, and Xiaojin Wu for their kind assistance with the images and Douglas Osto for granting permission to reproduce the lengthy excerpt from his translation. At the Cleveland Museum of Art, Howard Agriesti, Katie Kilroy Blaser, David Brichford, Moyna Stanton, and Dean Yoder were instrumental in providing excellent, color-correct photographs and securing the XRF data on pigments, the infrared photography, and accurate measurements of the Cleveland folio.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Translation of the text on Folio 348, by Douglas Osto (Osto 2013, pp. 16–17)

“… realized entrances of Dharma through various principles.

Then the great being, the bodhisattva Samantabhadra, said to Sudhana, the merchant-banker’s son, this: ‘O Son of Good Family, did you see my miracle?’

Sudhana said, ‘I saw, Noble One. But only one claiming to be a tathāgata would understand a miracle so inconceivable.’

Samantabhadra said, ‘O Son of Good Family, for eons equal in number atoms in buddha lands far beyond description, I have practiced desiring the mind of omniscience. Within every single great eon I met with the tathāgatas equal in number to the atoms in buddha lands far beyond description, leading to the purification of my mind of enlightenment. And within every single great eon, I performed great sacrifices that were proclaimed in all worlds and furnished with the abandonment of all—this state of the requisite of merit for omniscience teaching all beings. Within every single great eon, I made renunciations equal in number to the atoms in buddha lands far beyond description. Longing for the factors of omniscience, I made extreme renunciations. Within every single great eon I gave up bodies far beyond description; I gave up great empires, villages, towns, cities, countries, kingdoms and capitals, dear and charming communities of followers who were difficult to give up, sons, daughters and wives. Out of care for the knowledge of the buddhas through an indifference to my body and life, I gave up the flesh of my own bodies. I gave up blood from my own bodies to beggars; I gave up my bones and marrow; my limbs and body parts; my sense organs such as my ears, noses, eyes, and tongues from my own mouths. And within every single great eon, I gave up my own heads equal in number to the atoms in buddha lands far beyond description, longing for the head of supreme omniscience arisen from all worlds out of my own bodies.

Just as it was in every single great eon, so it was in oceans of great eons equal in number to the atoms in buddha lands far beyond description. Within every single great eon, I, the supreme lord, honored, praised, respected and worshipped the tathāgatas equal in number to the atoms in buddha lands far beyond description …’”

References

- Allinger, Eva. 2008. An Early Nepalese Gaṇḍavyūhasūtra Manuscript: An Attempt to Discover Connections Between Text and Illuminations. In Religion and Art: New Issues in Indian Iconography and Iconology. Edited by Claudine Bautze-Picron. London: The British Association for South Asian Studies, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bautze-Picron, Claudine. 1995. Between men and gods: Small motifs in the Buddhist art of eastern India, an interpretation. In Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art, Proceedings of a seminar held at Leiden University, 21–24 October 1991. Edited by van Kooij, Karel Rijk and Hendrik van der Veere. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bautze-Picron, Claudine. 2008–2009. Review Article: Chefs-d’oeuvre du delta du Gange, Collections des musées du Bangladesh, Catalogue réealisée sous la direction de Vincent Lefèvre et Marie-Françoise Boussac, Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux/Établissement public du musée des arts asiatiques Guimet, 24 octobre 2007-3 mars 2008, 2007. The Journal of Bengal Art 13–14: 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, Milo Cleveland. 1966. Painting and the Minor Arts. In The Arts of India and Nepal: The Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 97–185. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Pia. 1991. The Buddha and the Naked Ascetics in Gandharan Art: A New Interpretation. East and West 41: 121–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deegalle, Mahinda. 2004. Theravāda Pre-understandings in Understanding Mahāyāna. In Three Mountains and Seven Rivers: Prof. Musashi Tachikawa’s Felicitation Volume. Edited by Shoun Hino and Toshihiro Wada. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, David. 1992. Monk, Houselolder, and Tantric Priest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, Shin’ichiro Hori. 2019. On the Exact Date of the Pañcarakṣā Manuscript Copied in the Regnal Year 39 of Rāmapāla in the Catherine Glynn Benkaim Collection. Bulletin of the International Institute for Buddhist Studies 2: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kramrisch, Stella. 1964. The Art of Nepal. New York: Asia Society, Inc., New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sherman E. 1964. A History of Far Eastern Art. New York: H.N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Todd Thornton, and Jinah Kim. 2019. Dharma and Punya: Buddhist Ritual Art of Nepal. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Rob. 2014. Collecting Paradise: Buddhist Art of Kashmir and Its Legacies. Evanston: Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University and New York, Rubin Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Osto, Douglas. 2008. Power, Wealth, and Women in Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Osto, Douglas. 2009. The Supreme Array Scripture: A New Interpretation of the Title “Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra”. Journal of Indian Philosophy 37: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osto, Douglas. 2010. A New Translation of the Sanskrit Bhadracarī with Introduction and Notes. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Osto, trans. 2013. The Supreme Array Scripture. Chapter 55: The Vow to Follow the Course of Samantabhadra. Available online: http://douglasosto.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Supreme-Array-Scripture.chapter-55.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Pal, Pratapaditya. 1978. The Arts of Nepal, Part II. Painting. Leiden-Köln: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 1989. A Verse from the Bhadracarīpraṇidhāna in a 10th Century Inscription found at Nalanda. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 12: 149–57. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkellner, Ernst. 1995. Sudhana’s Miraculous Journey in the Temple of Ta Pho. Serie Orientale Roma LXXVI; Roma: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Trubner, Henry, and Paul Macapia. 1973. Asiatic Art in the Seattle Art Museum: A Selection and Catalogue. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya, Parasurama Lakshmana. 1960. Gandavyuhasutra. Darbhanga: Mithila Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Sanskrit Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Vigasin, Alexey. 2013. A Unique Gaṇḍavyūha Manuscript in Moscow. Bulletin d’Études Indiennes 31: 253–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, Heinrich. 1955. The Art of Indian Asia. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The folios are widely dispersed. I am aware of the following: 144 folios plus two wooden covers painted on the inner sides in the State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow; 9 folios in a private collection; 7 folios in the Cleveland Museum of Art; 6 folios in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; 4 folios at the Asia Society, NY; 4 folios at the San Diego Museum of Art; 3 folios at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; 3 folios at the Harvard Art Museums; 2 folios at the Brooklyn Museum, 2 folios at the Seattle Art Museum, and 1 folio at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. |

| 2 | The title of the manuscript has been variously translated, including the following: “Structure of the World” or “Entry into the Realm of Reality”. Douglas Osto has made a cogent argument for “The Supreme Array Scripture” as the preferred translation (Osto 2009). |

| 3 | In 1955, Heinrich Zimmer published in black and white the recto and verso of Folio 348, along with images of the paintings from Folio 94, which is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art (1955.49.2.a), and Folios 4, 19, and 102 in the Harvard Art Museums (1984.503, 1985.351.4, and 1984.504). He described them as “Miniatures from a twenty-page palm-leaf manuscript. Pāla period, 11th century A.D., from the Collection of Mr. Kaikoo M. Heeramaneck, Bombay. ((Zimmer 1955), vol. I, p. xvii and Pl. C1 A). In 1978, Pratapaditya Pal published a cropped image in black and white of the central scene of Folio 348 verso, but he offered no remark about the image (Pal 1978, figure 34). |

| 4 | Alexey Vigasin notes that the paleography of the text is closely related to a manuscript dated 1082 (Vigasin 2013, p. 256): “The Moscow manuscript of the Gaṇḍavyūha must be later than that, but probably not more than a few decades only.” Milo Cleveland Beach appears to have been the first to identify this Gaṇḍavyūha as made in Nepal during the early 12th century (Beach 1966, p. 105). Pratapaditya Pal provides a list of several publications in which pages from this manuscript appear under varying attributions (Pal 1978, p. 47, note 4). In 1964, Stella Kramrisch had suggested that the work was possibly a Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha from eastern India but linked the painting styles to those of Nepal (Kramrisch 1964, 43, 100, and 144 no. 78). In the same year Sherman Lee considered it to have been from Bengal, but he correctly identified the text as a Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra (Lee 1964, p. 119, colorplate 9 above). In 1973, two leaves in the Seattle Art Museum were misidentified as being from a Prajñāpāramitā from Bengal (Trubner and Macapia 1973, p. 113). Since then, scholars have agreed that the manuscript was copied and painted in Nepal during the late 11th to early 12th century. |

| 5 | Alexey Vigasin published a transcription of the simple colophon that identifies the text: āryagaṇḍavyūhāt mahādharmaparyāyāt yathālabdhaḥ sudhanakalyānami[tra pa]ryupāsitacaryaikadeśaḥ samāptah// (Vigasin 2013, p. 255).

|

| 6 | (In her Appendix I, Allinger provides a useful list of the 38 folios, their present locations, and the lines of text on each leaf (Allinger 2008, pp. 160–62) from a published version of the Sanskrit manuscript (Vaidya 1960). |

| 7 | Harvard Art Museums 1984.503–505 and 1985.351.4 (Lewis and Kim 2019, pp. 102–103). |

| 8 | Folios 186, 188, 191, 194, 230, 324, and 333 have two paintings. Vigasin published Folios 230 and 333 in black and white (Vigasin 2013, p. 263). Sometimes, the second painting is much smaller in size, taking up only the height of two lines of text plus the margin, and it interrupts the text field in a way that the main paintings do not. Other folios have only the white preparatory ground applied to the small fields, which can occur anywhere on the page, but they have not been painted with imagery. |

| 9 | I am grateful to Phyllis Granoff and Christopher Clarke for their assistance in identifying the section of the Sanskrit text on Folio 348 and locating Douglas Osto’s unpublished translation of the Ārya-Samantabhadra-caryā-praṇidhāna-rāja (Osto 2013). |

| 10 | It was translated into Chinese twice as an independent text, and excerpts are found in epigraphical contexts (Osto 2010, p. 2). For its appearance as a dhāraṇī in an epigraphical context, see (Schopen 1989). For a discussion of the use of the Bhadracarī as a dhāraṇī, see (Osto 2010, p. 7). |

| 11 | The only Chinese version of the Gaṇḍavyūha that includes the Bhadracarī is one that was translated from an eighth-century Sanskrit version (Osto 2010, p. 2). |

| 12 | For a discussion of the central role of Mañjuśrī in the Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra, see (Osto 2008). |

| 13 | XRF readings taken in the paper conservation lab of the Cleveland Museum of Art found a high mercury content in the red background, indicating the use of the pigment vermillion or cinnabar, which contains mercury sulfide. |

| 14 | The artist used a mixture of ultramarine (lapis lazuli) and orpiment to create the blue skin of this figure, according to readings taken with the portable XRF device in the paper conservation lab of the Cleveland Museum of Art. |

| 15 | For the date of this manuscript, see (Hori 2019). |

| 16 | Tīrthikas have been depicted as naked, showing genitals, in the Buddhist sculpture of Gandhara since the early centuries CE (Brancaccio 1991). |

| 17 | The blue of the robe is painted with pure lapis lazuli. |

| 18 | The white is a calcite or kaolinite, not a lead-based white pigment. |

| 19 | The blue robe (nīlapaṭa) was worn by monks of a Theravāda sect called Sammitīya (Deegalle 2004, p. 63, note 53). |

| 20 | This type of pointed cap is worn by priests in northeastern India and Nepal ((Bautze-Picron 2008–2009, p. 12) and (Lewis and Kim 2019, p. 94)). |

| 21 | See, for example the Vajrapāṇi sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art, 1971.14 in (Linrothe 2014, pp. 90–91). |

| 22 |

|

| 23 | Phyllis Granoff explained: “The Gaṇḍavyūha in this section has this phrase pāṇimegha, clouds of hands. I have always taken it just to be a rather neutral pluralizer. The idea is that Samantabhadra appears everywhere, and each of these millions of Samantabhadras puts his hand on the head of Sudhana, transferring some special knowledge in doing so. The many hands are pāṇi-meghas. The painters have taken this literally to mean hands that come out of clouds. I think this could only be based on a Tibetan translation. I don’t think a Sanskrit reader would do this. That raises some interesting questions about the source of the iconography?” Phyllis Granoff (Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA). 2019. Personal communication. |

| 24 | It is Phyllis Granoff who noted this connection. On Folio 22, on the verso of the leaf where the painting in Figure 16 is found, are verses describing the samādhi experienced by Samantabhadra, in which there are enlightened beings everywhere that light up the extensive Buddha fields, and imperishable “clouds of bodhisattvas” come from all ten directions.

|

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).