1. Introduction

Torpedo is the main weapon to damage underwater targets. In order to resist its damage effect, modern submarine protection technology continues to develop, and a special protection structure has been added to resist underwater explosion. This makes the traditional explosive torpedoes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], which rely on a single underwater explosion shock wave and bubble pulsation damage, have limited energy utilization and limited damage efficiency in the face of enhanced protection. In this context, the shaped charge torpedo warhead can form shaped charge jet through directional blasting to realize the initial penetration of the protective structure, carry out secondary loading combined with subsequent bubble pulsation [

6,

7,

8], which poses a more severe challenge to the ship protection system, and also put forward a higher request for the protection design to resist multi-level and sequential attacks. Therefore, it is necessary to study the impact process of shaped charge jet to underwater targets.

Yaziv [

9] investigated the penetration behavior of shaped charge jets in water and demonstrated that, although such jets exhibit superior penetration capability compared with long-rod projectiles, their velocity decays rapidly in water and they are prone to fragmentation. Wang Haifu [

10] focused on the underwater dynamic response of rod-shaped jets, revealing that the stand-off distance significantly influences jet morphology, velocity distribution, and penetration performance in aquatic environments. Wang Yajun [

11] analyzed the velocity attenuation and mass loss characteristics of explosively formed penetrators (EFPs) in water, concluding that EFPs lose their penetration capability after traversing a distance of approximately five charge diameters. Liu Xiaobo [

12] examined the applicability of different liner geometries under various casing configurations and water-layer thicknesses, and conducted a comparative evaluation of the damage efficiency of different shaped charge jets. Gu [

13] reported enhanced underwater penetration performance of shaped charge jets and proposed a theoretical model describing jet formation in water. Yu [

14] investigated the coupled interactions among shock waves, pulsating bubbles, and penetrators during underwater shaped charge detonation, and discussed the effects of liner design and explosive mass on this coupling behavior. In addition, Zhang Zhifan and co-workers [

15,

16,

17] systematically studied the damage mechanisms associated with blasting, explosively formed projectiles, and linear shaped charges.

In addition, numerous studies have focused on enhancing the underwater penetration capability of shaped charge warheads through liner structural optimization. Ji Xiang and co-workers [

18,

19,

20] systematically investigated the effects of liner geometric parameters on jet formation characteristics and penetration performance in water, and identified optimal liner configurations tailored for underwater operating conditions. Furthermore, Yang et al. [

21,

22,

23] proposed a novel liner design that exploits the cavitation effect induced by high-velocity penetrators in water. The resulting tandem penetrator configuration utilizes the cavitation channel generated by the leading penetrator to reduce the hydrodynamic resistance experienced by the following penetrator, thereby significantly enhancing the overall penetration depth and damage efficiency.

A considerable body of research has been devoted to the underwater damage behavior of shaped charge formed penetrators. Existing studies have predominantly focused on warhead structural optimization and the dynamic response of penetrators during underwater motion, with emphasis on improving penetration depth and perforation size. However, the damage mechanisms of shaped charge jets acting on targets under underwater conditions have not been thoroughly investigated, and there is almost no systematic research on the interaction and coupling mechanisms among multiple damage elements during underwater penetration, leaving these complex processes poorly understood. To address this gap, the present study combines numerical simulations with underwater experimental investigations to systematically analyze the damage characteristics of individual damage components during the penetration of shaped charge jets into multilayer targets in a water environment. In addition, a theoretical model describing the radial expansion of penetration holes in multilayer targets induced by underwater shaped charge jets is developed, enabling a quantitative characterization of the hole expansion process in thin targets under underwater penetration conditions.

3. Analysis of Numerical Simulation Results

3.1. Typical Process of Shaped Charge Warhead Underwater Penetrating Multilayer Target

Figure 3 illustrates the representative evolution of a shaped charge warhead penetrating a multilayer target configuration in an underwater environment. Upon detonation of the shaped charge in water, the detonation wave propagates axially toward the liner, driving its collapse and generating a high-velocity shaped charge jet. Simultaneously, the detonation products expand rapidly outward, inducing an initial shock wave in the surrounding water that propagates in an approximately ellipsoidal form. At t = 20 μs, the forward-propagating shock wave reaches the surface of the first target plate prior to the arrival of the jet. Owing to the axial presence of the liner and the intervening air region, the effective action range of the shock wave is confined to the boundary of the air domain, leading to pronounced plastic deformation of the first target plate. As time progresses to t = 30 μs, the jet perforates the first plate and enters the water medium. Under the combined influence of the shock wave and jet loading, the perforation in the first target plate exhibits backward bulging. Subsequently, at t = 35 μs, the forward shock wave impinges on the second target plate. Due to rapid attenuation caused by reflection and scattering during propagation in water, the peak pressure of the shock wave diminishes substantially, rendering it insufficient to induce notable damage to the second plate. At t = 85 μs, the shaped charge jet initiates penetration of the second target. During its high-speed travel through water, the fluid ahead of the jet is intensely compressed, generating a ballistic wave that transmits pressure forward. As a result, bending deformation of the target plate occurs prior to direct jet impact. After perforation, the resulting hole in the second plate exhibits deformation opposite to that of the first plate, characterized by forward bulging.

Because of the pronounced velocity gradient within the shaped charge jet, fragmentation occurs during underwater propagation. The leading jet segment violently interacts with the surrounding water, producing a cavity filled with water vapor and detonation products. As the fragmented jet travels within this cavity, fluid resistance is markedly reduced, leading to significantly lower velocity attenuation, resembling jet motion in an air environment. With continued penetration, the cavity rapidly expands along the jet trajectory and exerts compressive loading on the surrounding water, thereby inducing secondary damage effects on the target plates. By t = 190 μs, the overall deformation of the second target plate is further intensified.

As the penetration process proceeds, repeated interactions with the water medium and successive target plates continuously dissipate the jet’s kinetic energy. At t = 355 μs, the shaped charge jet perforates the first four target plates and reaches the surface of the fifth plate, at which point its penetration capability is nearly exhausted. Under the sustained expansion and compression effects of the cavity, the fifth target plate is eventually perforated at t = 500 μs. The cavity continues to develop and propagates toward the aftereffect target at t = 800 μs; however, no significant damage to the aftereffect target is observed.

3.2. Underwater Damage Mechanism of Shaped Charge Warhead

To characterize the damage response of multilayer targets subjected to underwater shaped charge jet penetration, the numerical simulation results of multilayer target penetration by a shaped charge jet in both water and air are compared and analyzed. t = 800 μs, and when the penetration process is completed, the deformation state of the multilayer target in the numerical simulation results is shown in

Figure 4.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the damage capability of the shaped-charge jet in a water environment is significantly greater than that in air. Under underwater penetration conditions, the maximum deflections of the individual target plates are 2.42, 2.75, 6.80, 15.0, and 15.6 times those observed in air, respectively. Meanwhile, the corresponding hole diameters increase to 1.10, 1.17, 1.57, 1.81, and 1.06 times those obtained under air conditions.

These differences primarily arise from the pronounced disparity in physical properties between water and air. Meanwhile, the back face is much more severely deflected when the shot occurs in water, which is likely attributable to the formation of a bow shock [

27]. Owing to the much higher density of water, the expansion of detonation products experiences substantially greater resistance, which prolongs their interaction with the first target plate and results in markedly different deformation responses in the two environments. For the subsequent target plates, the observed deformation differences are mainly governed by the cavitation effect. During underwater penetration, the shaped-charge jet generates a cavity that continuously expands along the penetration path, exerting sustained loading on both the surrounding water and the target plates, thereby intensifying their deformation. Consequently, the deformation evolution of multilayer targets in water differs fundamentally from that in air.

The penetrator (shaped-charge jet) then passes through the targets within a very short time due to its high velocity, and the jet–target interaction duration is limited. Therefore, the hole size and local deflection caused by jet penetration can be directly identified from the simulation results at the end of the penetration stage. In contrast, the cavity acts on the target over a much longer time scale and produces a sustained loading process. The target deformation continues after the penetration process has ended and gradually stabilizes. Consequently, the cavity-induced hole expansion and deflection are obtained by comparing the final stabilized deformation state with the deformation state immediately after jet penetration.

To characterize the perforation behavior of each target plate during shaped charge jet penetration, statistical analyses were conducted on the jet diameter prior to impact (

Dj), the initial hole diameter produced by the jet (

D0), and the final hole diameter of the target plate (

Df), as illustrated in

Figure 5. The results indicate a clear positive correlation between the pre-impact jet diameter

Dj and the resulting perforation size, with larger jet diameters leading to increased hole dimensions in the target plates.

A comparison between the initial and final hole diameters further reveals the contribution of cavity expansion to the perforation process. For the first target plate, located in the jet entry region into the water, the influence of cavity expansion is relatively limited, with the initial hole diameter accounting for approximately 93% of the final perforation size. In contrast, for the subsequent four target plates, the D0/Df ratios range from 72% to 78%, indicating that cavity expansion plays a significant role in enlarging the perforation. On average, cavity-induced expansion increases the hole diameter by approximately 25%.

Figure 6 illustrates the temporal evolution of target plate deflection during the penetration process. Among the five target plates, only the first plate exhibits deflection in the negative direction, whereas the remaining four plates show a rapid increase in deflection followed by a stabilization phase, with the overall trend resembling an exponential growth behavior.

The observed discrepancies arise from the different damage mechanisms governing each target plate. The first plate serves as a pressure release boundary and is exposed to the combined action of the shock wave, the shaped charge jet, and detonation products. Consequently, its maximum deflection exhibits an initial reduction followed by a subsequent increase, and deformation continues to evolve even after jet penetration has ceased. By contrast, the deformation of the remaining four plates is mainly driven by jet penetration and cavity-induced loading. After the completion of jet penetration, the cavity expansion rate decreases significantly, resulting in negligible additional deflection.

Further observation reveals that noticeable deflection occurs in the first two target plates prior to direct jet impact. This phenomenon arises from the rapid attenuation of the shock wave during propagation in water, which limits its damaging effect mainly to the front target plates. The damage contribution of cavity expansion is predominantly concentrated on the last four target plates, with the average cavity-induced deflection accounting for approximately 46% of the maximum deflection.

4. Radial Reaming Theory of Shaped Charge Projectile Penetrating Multilayer Target Under Water

Because the characteristic time scale of the jet–target interaction is on the order of microseconds (μs), whereas bubble pulsation phenomena typically occur on a millisecond (ms) time scale, there exists a significant separation between these two processes. As a result, the influence of bubble pulsation on the dominant jet penetration process is considered limited and was therefore not included in the numerical simulations.

Based on the numerical simulation results of shaped-charge jets penetrating multilayer spaced targets in an underwater environment, and excluding the damage effects induced by bubble pulsation, the interaction between the jet and the target plates can be divided into two primary phases. The first phase involves the direct penetration of the target by the jet, resulting in the formation of an initial perforation. The second phase corresponds to the subsequent expansion of this perforation caused by the propagation of the cavity generated during jet advancement. On this basis, the perforation diameter of thin targets subjected to underwater shaped-charge jet penetration can be expressed as:

For the convenience of theoretical analysis, the following assumptions are introduced for the high-velocity penetration of a shaped charge jet into a homogeneous target plate: the velocity and diameter of the shaped charge jet are linearly distributed along the jet length; the target plate is treated as an incompressible material; the initial radial expansion velocity and initial pressure are determined by the radial flow of the jet; and the radial reaming process is assumed to be inertia-dominated, with other effects neglected.

According to basic fluid dynamic theory, the radial expansion of the penetration hole driven by the jet requires that the combined static and dynamic pressures on either side of the impact interface remain balanced. When the strength effects of the target material are neglected, this condition can be described using a modified Bernoulli formulation, expressed as:

Here, Vcj denotes the radial velocity of the shaped charge jet during penetration, while ucj represents the radial penetration velocity. The parameters ρt and ρj correspond to the densities of the target plate and the jet, respectively, and Rt is the acoustic impedance of the target material.

Within the Eulerian reference frame, the shaped charge jet approaches the target from a finite distance with an effective velocity of

Vj −

u [

28], as shown in

Figure 7.

Considering that the pressure of the jet in the incoming flow region can be approximated as zero, the relationship between the axial velocity and the radial velocity during the jet penetration process can be expressed as follows:

In this expression, Vj denotes the axial velocity of the shaped charge jet during penetration, while u represents the corresponding axial penetration velocity.

The radial velocity

Vcj in the process of jet penetration can be obtained from Equation (7):

According to the Held equation [

29], the relationship between shaped charge jet radial penetration velocity

ucj and target aperture

D0 is:

where

Dj is the diameter of the head before the jet hits the target, and

D0 is the aperture of the target plate.

When the radial penetration velocity of shaped charge jet

ucj = 0,

D0 is the maximum value, and then the initial aperture of jet to target can be obtained,

After the jet penetration, the cavity in high-speed motion drives the inflow water to carry out secondary reaming on the target plate. Assuming that the cavity density is the density of water during the reaming process, and the impedance of the target plate during the reaming process is the same as that during the jet hole opening process, it can be seen from the formula that the radial penetration velocity

uca of the cavity to the target plate is:

In combination with Equation (9), the reaming Δ

D of the cavity to the target plate can be expressed as:

The final aperture of shaped charge projectile penetrating thin target under water can be obtained by simultaneous Equations (4), (10) and (12):

5. Underwater Penetration Test of Shaped Charge Warhead

To validate the reliability of the numerical simulation results, underwater penetration experiments using a shaped charge warhead were conducted. The experiments were performed in a water tank with dimensions of 8 m × 8 m × 8 m. A schematic illustration of the experimental principle is provided in

Figure 8. The experimental setup mainly consisted of a target plate support frame, a warhead mounting structure, and lifting rings.

Homogeneous target plates with dimensions of 300 mm × 300 mm × 2 mm and the shaped charge warhead were securely mounted on support structures prior to testing. The assembled device was then lowered horizontally into the water tank using a crane. During the experiment, the target assembly was suspended horizontally in the water, while the shaped charge warhead was firmly fixed to the support structure and placed in direct contact with the surface of the leftmost target plate. The tail of the warhead was connected to a detonating wire. Once the experimental setup was completed, the detonator was initiated electrically, leading to the detonation of the shaped charge. Simultaneously with detonation, a high-speed camera was triggered to record the jet penetration process. The frame rate of the high-speed camera was set to 40,000 frames per second, and the camera was connected to a computer via a network cable. The recording process was controlled by the computer, which captured images within a time window of 2 s before and after detonation.

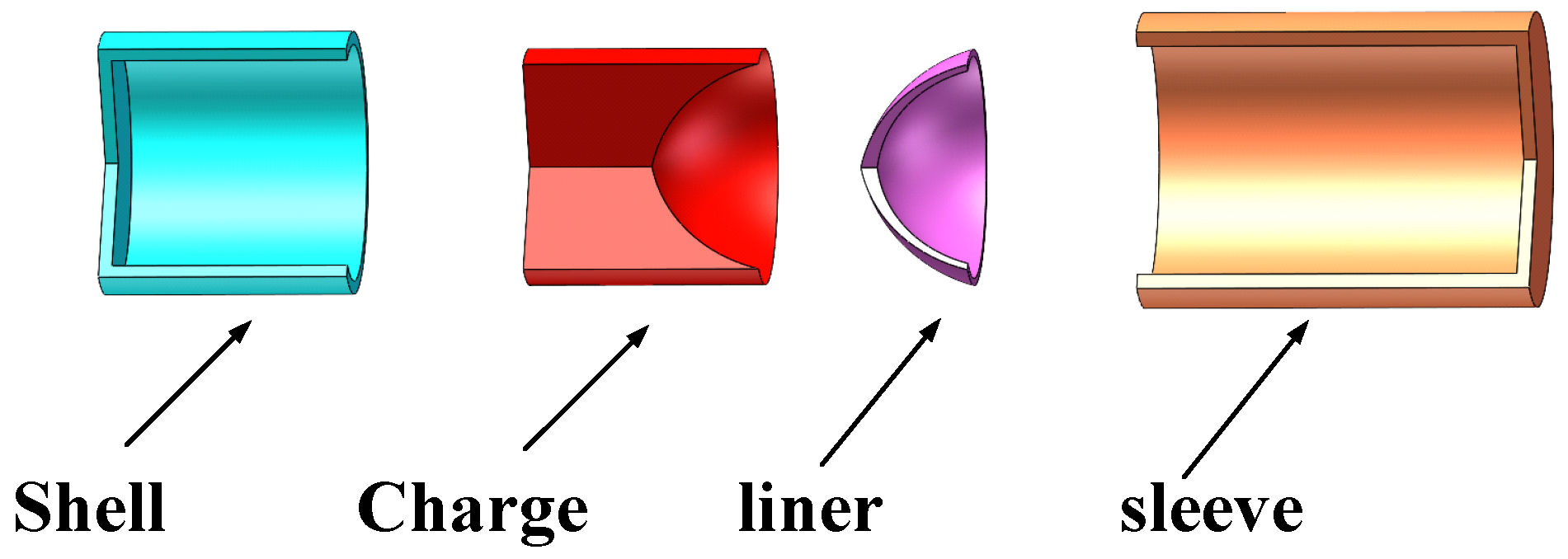

The structural layout of the shaped charge warhead is shown in

Figure 9a. The assembly mainly consists of a detonator base, a warhead casing, and a sleeve. To ensure watertightness, the detonator base is sealed with waterproof adhesive, while the components are mechanically connected through threaded interfaces. During the experiment, initiation is provided by an electronic detonator that ignites the booster charge, which subsequently initiates the main explosive.

The warhead is filled with 8701 explosive at a charge density of 1.71 g/cm

3. The explosive charge has a diameter and axial length of 36 mm, and the corresponding sleeve extends to a length of 72 mm. The liner configuration is shown in

Figure 9b. The liner is fabricated from copper and adopts a variable wall-thickness hemispherical geometry. The overall experimental arrangement is depicted in

Figure 9c.

The underwater penetration process of a shaped charge jet into multilayer spaced target plates is illustrated in

Figure 10, where the targets are numbered sequentially from Target 1 to Target 5 from left to right. Following detonation of the shaped charge, the liner collapses along the axis to form a high-temperature, high-velocity metal jet. At t = 50 μs, the jet penetrates the first target plate and generates a strong impact on the surrounding water, leading to rapid vaporization and the formation of a cavity. By t = 250 μs, the jet successively penetrates the first four target plates; however, due to hydrodynamic resistance, the velocity of the jet tip decreases rapidly, and the jet reaches the fifth target plate at approximately t = 350 μs. During this process, the effective mass of the jet head is continuously dissipated under high-speed impact and interaction with the water medium, resulting in a progressive reduction in penetration capability. Consequently, the jet fails to perforate the fifth target plate by t = 450 μs. As time advances, the cavity continues to expand and exerts compressive loading on the target plate, eventually enabling penetration of the fifth plate and subsequent interaction with the witness target at t = 600 μs.

A comparative assessment of the underwater shaped charge experiments and the numerical simulations, including jet penetration time, cavity evolution, and damage characteristics of the multilayer spaced targets, demonstrates good agreement between the two approaches.

A statistical evaluation of the post-penetration damage characteristics of the target plates was performed, and the experimental observations are presented in

Figure 11. The shaped charge jet perforated all five layers of the water-backed spaced targets, while no apparent damage was observed on the witness target. Among the five target plates, the first plate suffered the most severe deformation. This behavior is primarily attributed to the fact that the first target plate was welded to the warhead support structure. During detonation, the support exerted prying forces on the welded region under the action of detonation products, resulting in pronounced tearing damage. Furthermore, the subsequent underwater bubble pulsation stage contributed to a further increase in the plastic deformation of the first target plate.

In contrast, the remaining four target plates exhibited relatively limited deformation. Their perforation morphology was characterized by typical petal-shaped openings, which are consistent with the failure features induced by shaped charge jet penetration.

Figure 12 compares the theoretical predictions, numerical simulation results, and underwater penetration experimental data of the shaped charge warhead. Owing to the fact that the numerical model focuses on the jet penetration stage and does not account for the subsequent bubble pulsation effects in water, a noticeable discrepancy is observed in the perforation size of the first target plate. However, for the remaining four target plates, the perforation characteristics predicted by the theoretical model, numerical simulations, and experiments exhibit strong agreement, with relative errors consistently within 10%. This high level of consistency provides robust validation of both the numerical simulation methodology and the proposed theoretical model.

The minor deviations observed among the three sets of results are primarily attributed to unavoidable experimental factors, including target buoyancy and mounting conditions during underwater testing, whereas the numerical simulations are performed under idealized assumptions. Overall, the close agreement between theory, simulation, and experiment confirms the effectiveness and reliability of the developed modeling approach for predicting the underwater penetration behavior of shaped charge warheads.