The Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing on the Dynamic Response of the Seabed Foundation in Front of a Slope Breakwater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physical Model Experimental Setup

2.1. Flume and Model Setup

2.2. Experimental Group Arrangement

2.3. Experimental Phenomena

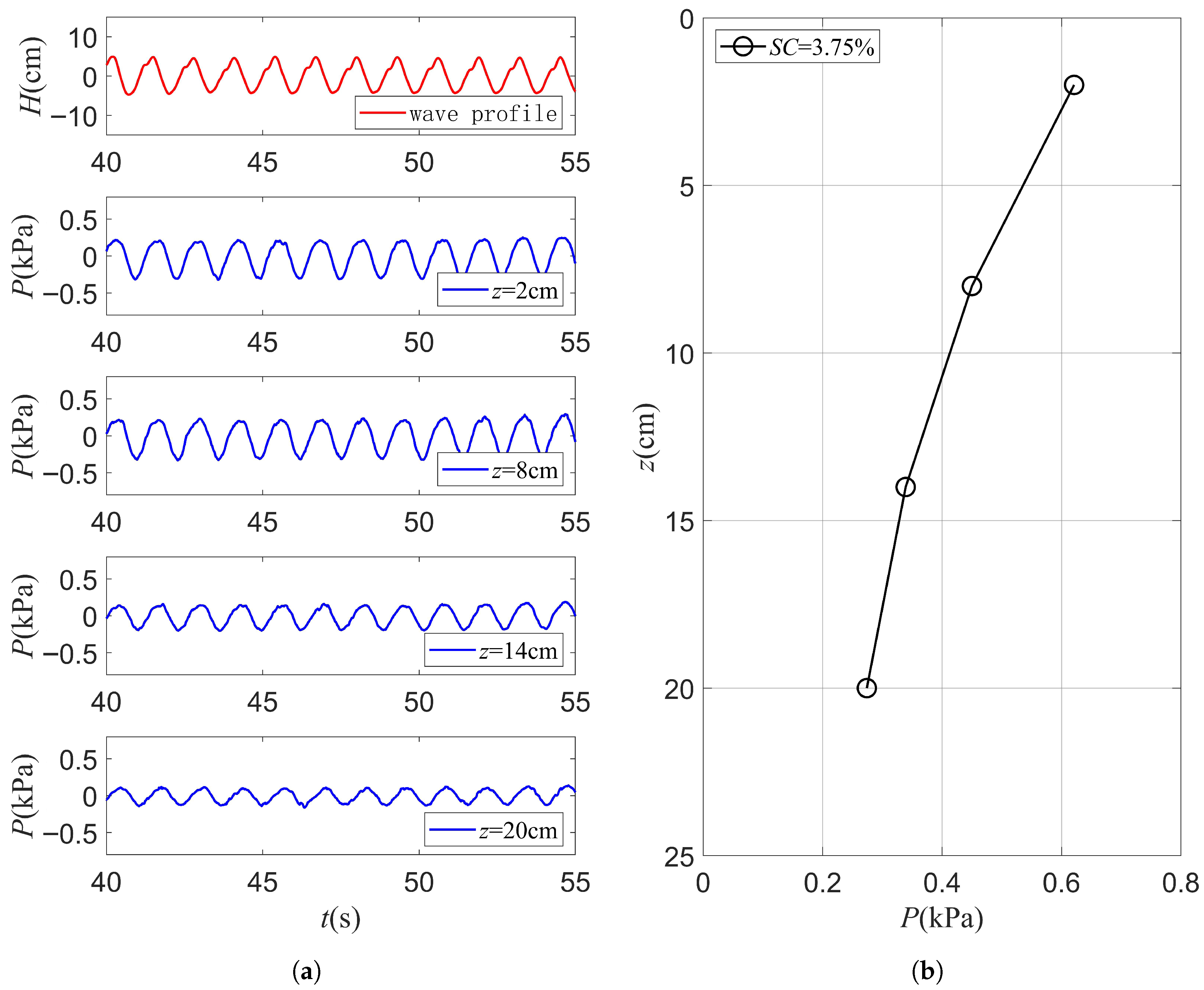

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing Ratio on the Vertical Attenuation Coefficient

3.2. Empirical Formula for Pore Water Pressure Response in Shell-Sand Mixed Seabeds Fronting Slope Breakwater

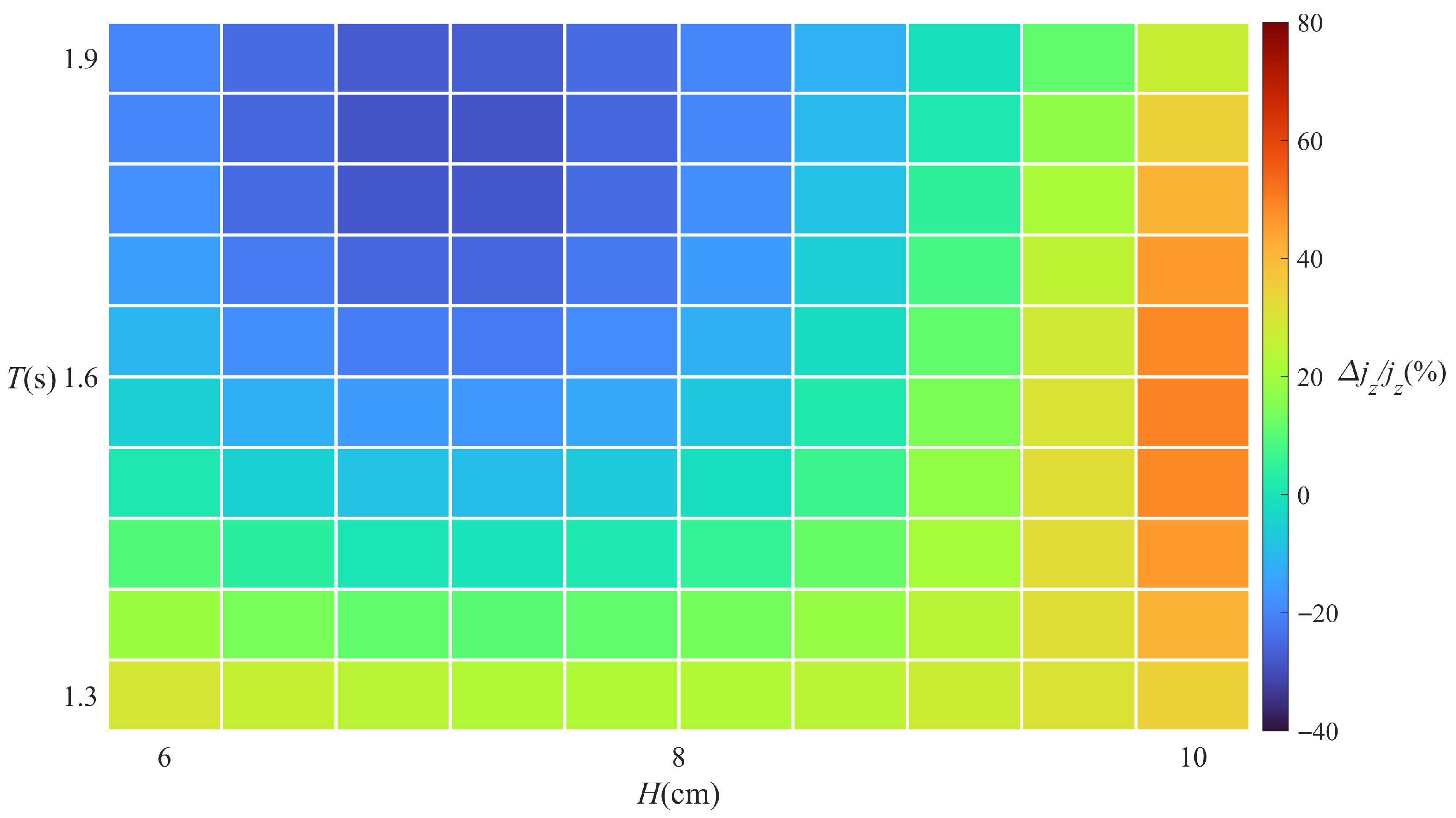

3.3. Parametric Analysis of Shell-Sand Mixing Effectiveness

4. Application of Shell-Sand Mixing in the West Coast of Africa and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Díaz-Carrasco, P.; Moragues, M.V.; Clavero, M.; Losada, M.Á. 2D water-wave interaction with permeable and impermeable slopes: Dimensional analysis and experimental overview. Coast. Eng. 2020, 158, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, Y.; Cevik, E.; van Gent, M.R.; Sahin, C.; Altunsu, A.; Tugce Yuksel, Z. Stability of berm type breakwater with cube blocks in the lower slope and berm. Ocean Eng. 2020, 217, 107985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, M.; Díaz-Carrasco, P.; Losada, M. Bulk Wave Dissipation in the Armor Layer of Slope Rock and Cube Armored Breakwaters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Tong, D.; Jeng, D.S.; Zhao, H. Numerical study for wave-induced oscillatory pore pressures and liquefaction around impermeable slope breakwater heads. Ocean Eng. 2018, 157, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jeng, D.S.; Liu, J. Seabed foundation stability around offshore detached breakwaters. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 111, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Guo, Y.; Guan, D. Experimental study of wave-induced dynamic response within the seabed around an impermeable sloping breakwater. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. On gravity waves propagated over a layered permeable bed. Coast. Eng. 1977, 1, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T. Wave-induced pore pressures and effective stresses in homogenous seabed foundations. Ocean Eng. 1981, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, B.; Jeng, D.S.; Hsu, J. Transient soil response in a porous seabed with variable permeability. Ocean Eng. 1996, 23, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.S.; Seymour, B. Response in seabed of finite depth with variable permeability. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1997, 123, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.S.; Seymour, B. Wave-induced pore pressure and effective stresses in a porous seabed with variable permeability. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 1997, 119, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Jeng, D.S. The effects of variable permeability on the wave-induced seabed response. Ocean Eng. 1997, 24, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Jeng, D.S. Response of Poro-Elastic Seabed to a 3-D Wave System: A Finite Element Analysis. Coast. Eng. 1996, 39, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiano, T.; Mase, H. Wave-induced porewater pressure in a seabed with inhomogeneous permeability. Ocean Eng. 2001, 28, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.S. Soil response in cross-anisotropic seabed due to standing waves. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1997, 123, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Jeng, D.S. Effects of variable shear modulus on wave-induced seabed response. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2000, 23, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, T.; Kirca, O.; Sumer, B.M.; Carstensen, S.; Fuhrman, D.R. Wave induced seabed liquefaction in a mixture of silt and seashelss. Coast. Eng. 2022, 178, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijendijk, A.; Hagenaars, G.; Ranasinghe, R.; Baart, F.; Donchyts, G.; Aarninkhof, S. The State of the World’s Beaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Koning, H.; Sellmeijer, H.; Van Hijum, E.P. On the response of a poro-elastic bed to water waves. J. Fluid Mech. 1978, 87, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.S. Porous Models for Wave-Seabed Interactions; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, J.; Menendez, M.; Losada, I.J. GOW2: A global wave hindcast for coastal applications. Coast. Eng. 2017, 124, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liang, B.; Shao, Z. A global climate analysis of wave parameters with a focus on wave period from 1979 to 2018. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2021, 111, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEARATES. Sea Ports in the World. 2024. Available online: https://www.searates.com/maritime (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Lloyd’s List. One Hundred Container Ports 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.lloydslist.com/one-hundred-container-ports-2023 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Caballero-Herrera, J.A.; Olivero, J.; von Cosel, R.; Gofas, S. An analytically derived delineation of the West African Coastal Province based on bivalves. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 28, 2791–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Shell-Sand Mixing Ratios SC (%) | Void Ratio e | Permeability Coefficient K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.75 | 0.76 | 4.41 |

| 2 | 7.5 | 0.69 | 4.16 |

| 3 | 15 | 0.59 | 3.15 |

| 4 | 30 | 0.57 | 3.11 |

| No. | Water Depth d (m) | Wave Height H (m) | Wave Period T (s) | Wavelength (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–5 | 0.228 | 0.06 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.27/1.77/2.24/2.72/3.19 |

| 6–10 | 0.228 | 0.08 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.27/1.77/2.24/2.72/3.19 |

| 11–15 | 0.228 | 0.10 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.27/1.77/2.24/2.72/3.19 |

| 16–20 | 0.228 | 0.12 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.27/1.77/2.24/2.72/3.19 |

| 21–25 | 0.292 | 0.06 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.36/1.94/2.50/3.04/3.57 |

| 26–30 | 0.292 | 0.08 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.36/1.94/2.50/3.04/3.57 |

| 31–35 | 0.292 | 0.10 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.36/1.94/2.50/3.04/3.57 |

| 36–40 | 0.292 | 0.12 | 1.0/1.3/1.6/1.9/2.2 | 1.36/1.94/2.50/3.04/3.57 |

| No. | Shell-sand Mixing Ratio SC (%) | Wave Height H (m) | Wave Period T (s) | Wavelength (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41–43 | 3.75 | 0.06 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 44–46 | 3.75 | 0.08 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 47–49 | 3.75 | 0.10 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 50–52 | 7.5 | 0.06 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 53–55 | 7.5 | 0.08 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 56–58 | 7.5 | 0.10 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 59–61 | 15 | 0.06 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 62–64 | 15 | 0.08 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 65–67 | 15 | 0.10 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 68–70 | 30 | 0.06 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 71–73 | 30 | 0.08 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| 74–76 | 30 | 0.10 | 1.3/1.6/1.9 | 1.94/2.50/3.04 |

| Term | Unstandardized Coefficient | Std. Error | Standardized Coefficient | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 0.927 | 0.127 | 7.328 | 0.001 | |

| lgSC | −0.413 | 0.037 | −0.385 | −11.299 | 0.001 |

| lgH_L | −0.205 | 0.099 | −0.094 | −2.079 | 0.040 |

| lgd_L | 2.852 | 0.152 | 0.861 | 18.786 | 0.001 |

| lgz_L | −0.342 | 0.024 | −0.504 | −14.491 | 0.001 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.938 | 0.881 | 0.876 | 0.0932397 |

| Wave Parameters | H = 1.5 m | H = 2.0 m | H = 2.5 m |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = 6.5 s | PPA Change: 37.6% | PPA Change: 44.6% | PPA Change: 46.5% |

| T = 8.0 s | PPA Change: 38.1% | PPA Change: 39.3% | PPA Change: 40.7% |

| T = 9.5 s | PPA Change: 30.8% | PPA Change: 31.4% | PPA Change: 31.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sui, T.; Lv, T.; Yang, M.; Zhu, H. The Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing on the Dynamic Response of the Seabed Foundation in Front of a Slope Breakwater. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010093

Sui T, Lv T, Yang M, Zhu H. The Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing on the Dynamic Response of the Seabed Foundation in Front of a Slope Breakwater. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleSui, Titi, Tianyu Lv, Musheng Yang, and Hang Zhu. 2026. "The Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing on the Dynamic Response of the Seabed Foundation in Front of a Slope Breakwater" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010093

APA StyleSui, T., Lv, T., Yang, M., & Zhu, H. (2026). The Influence of Shell-Sand Mixing on the Dynamic Response of the Seabed Foundation in Front of a Slope Breakwater. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010093