Geological Characteristics and a New Simplified Method to Estimate the Long-Term Settlement of Dredger Fill in Tianjin Nangang Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

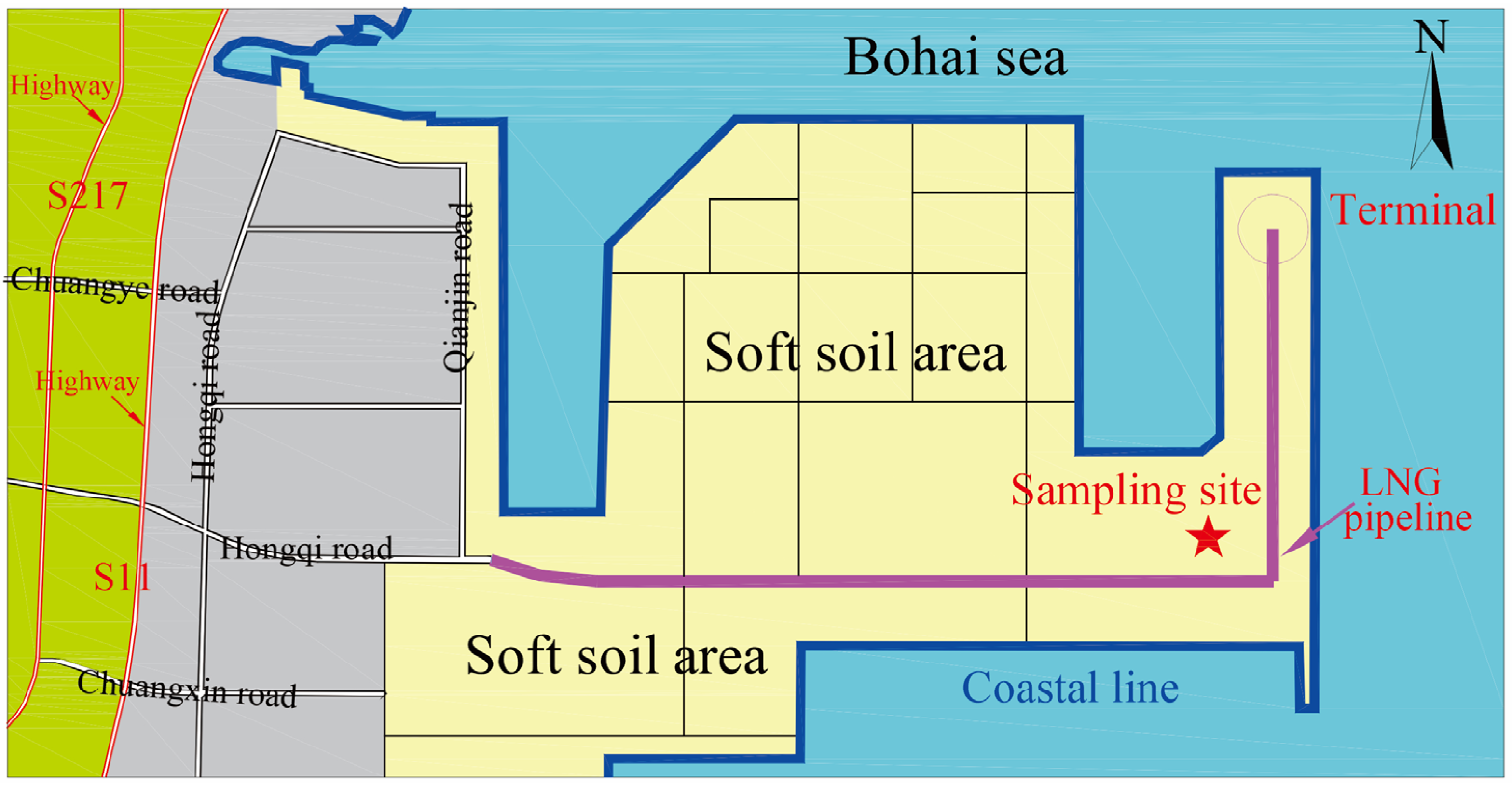

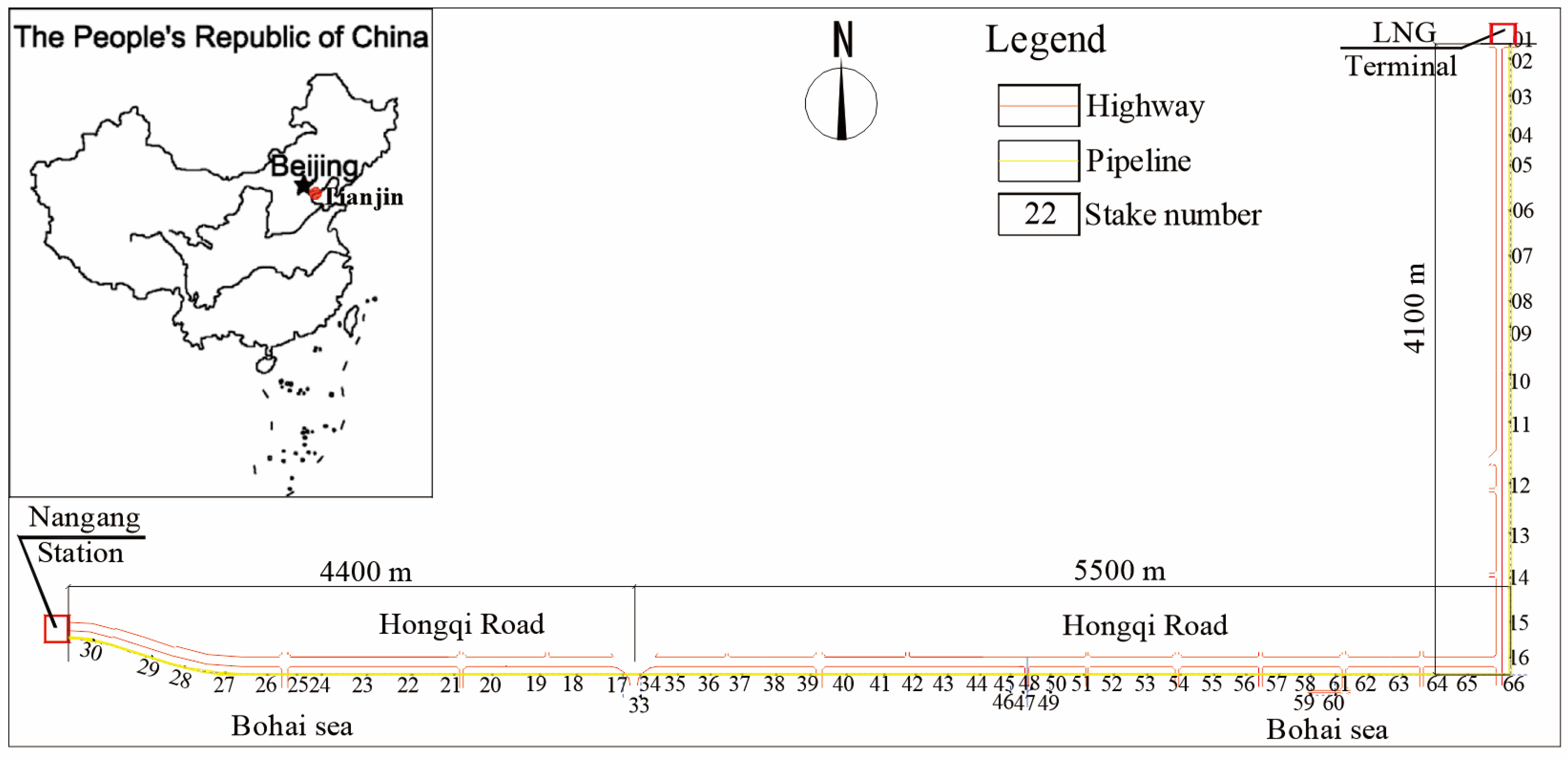

2. Site Characterization in the Tianjin Nangang Region

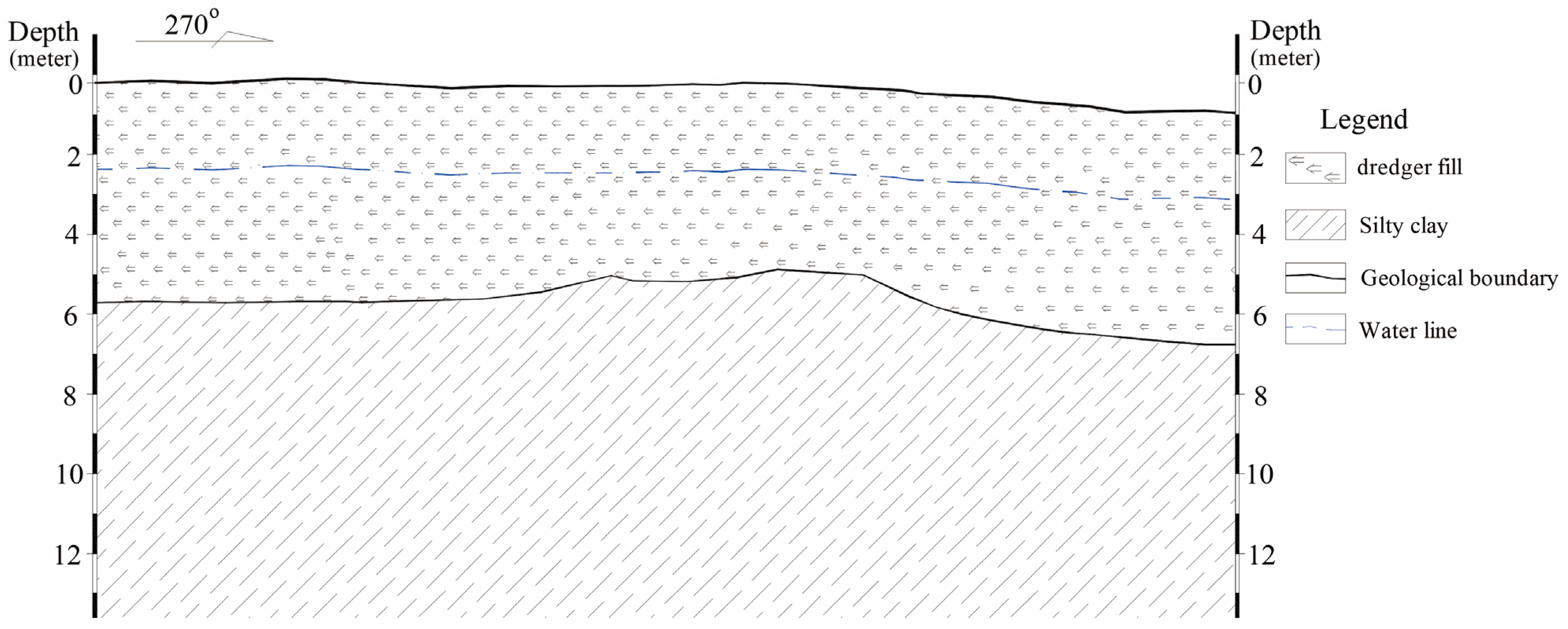

2.1. Geological and Subsoil Conditions

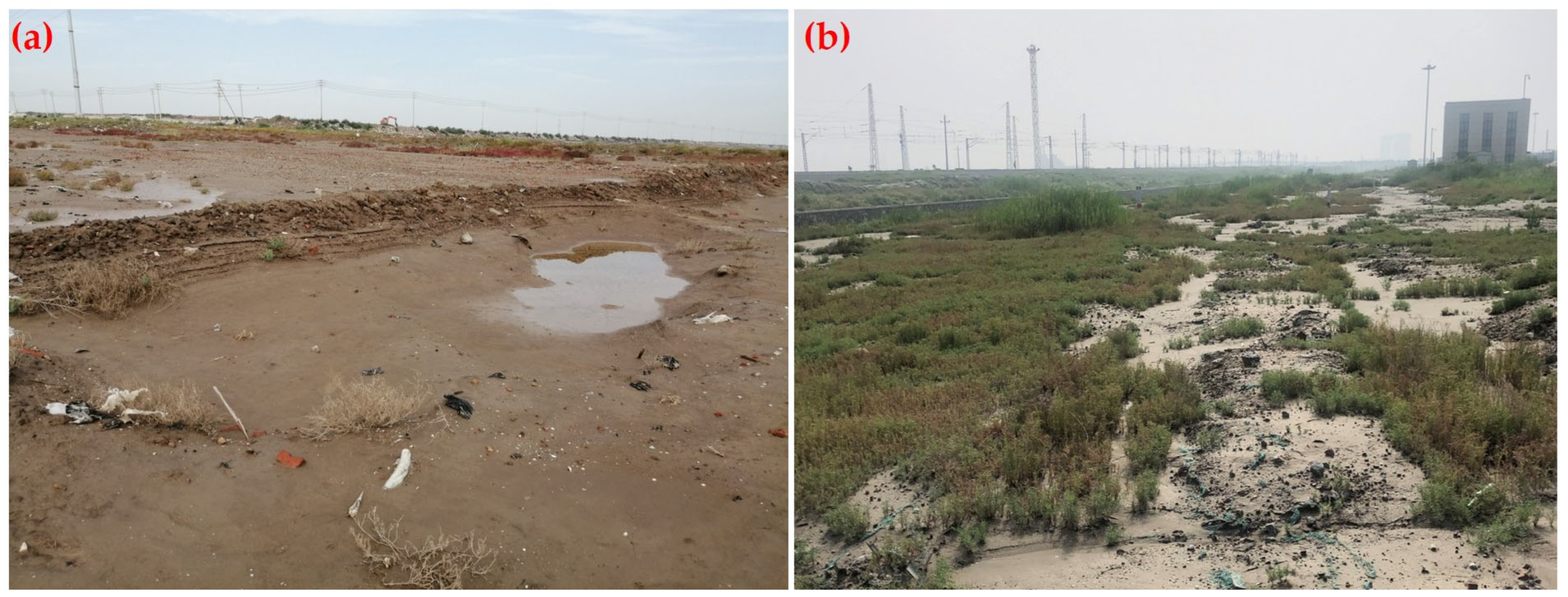

2.2. Effects of Settlement in Dredger Fill

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Soft Soil Samples

3.2. Characterization

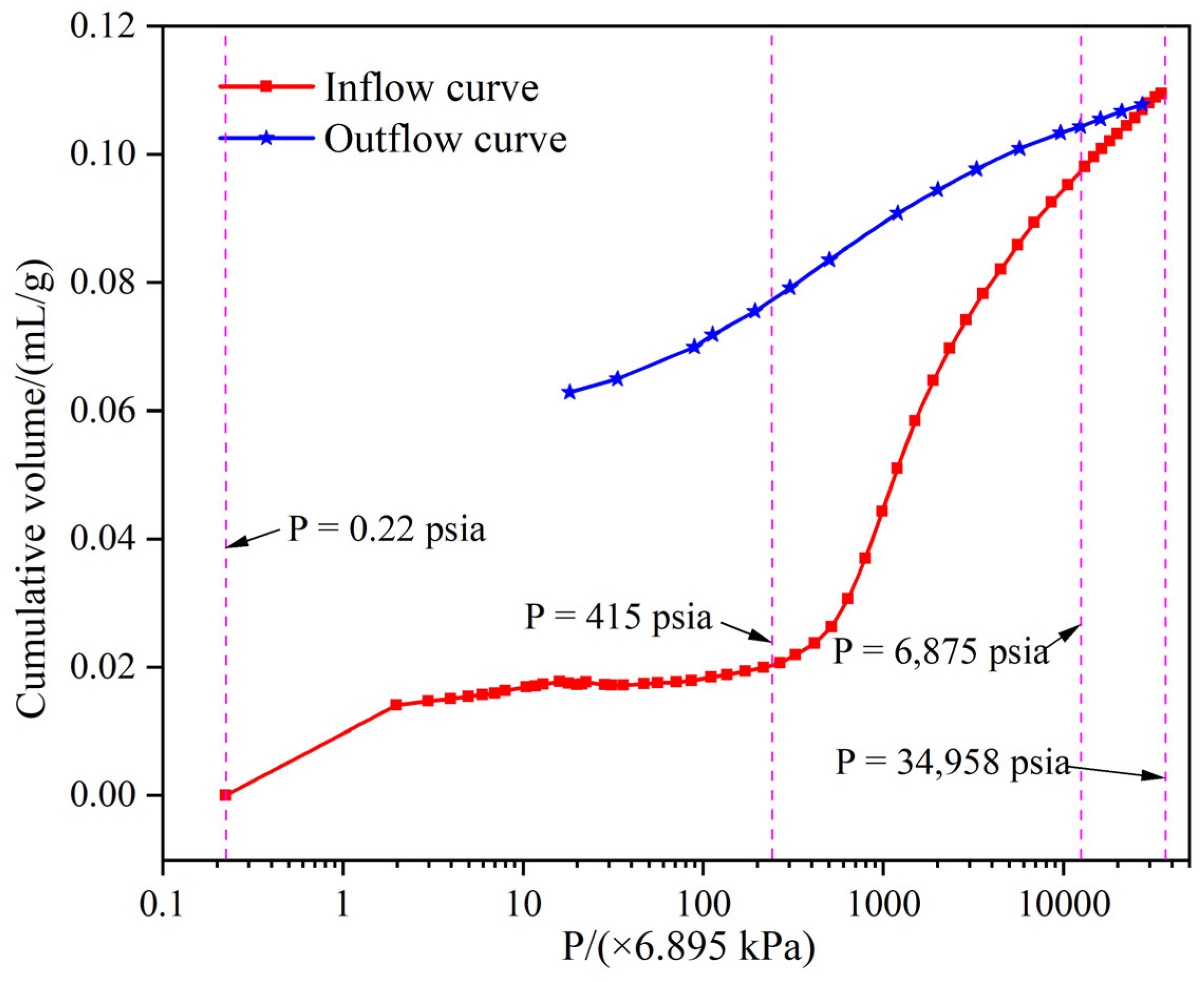

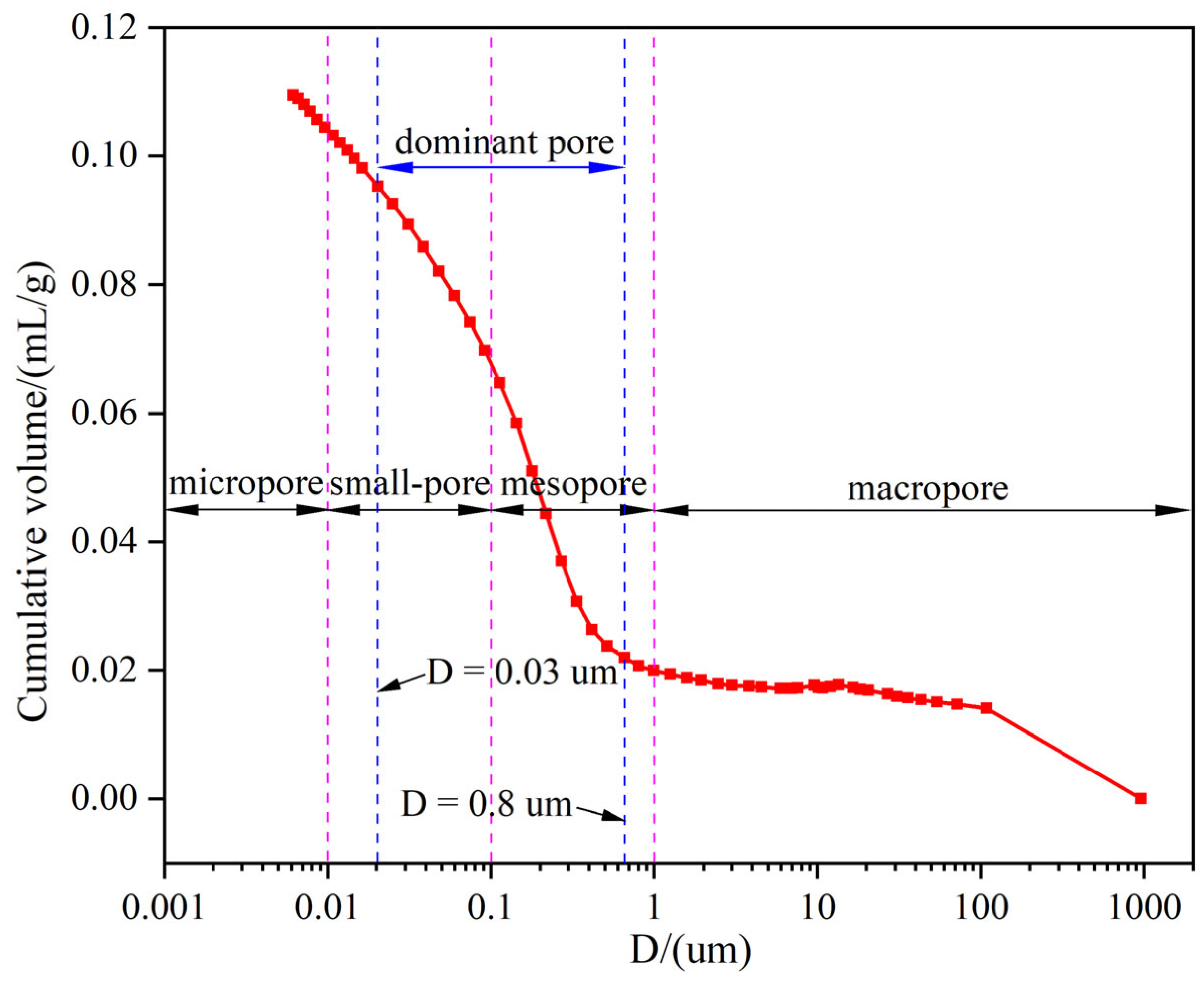

3.3. Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry

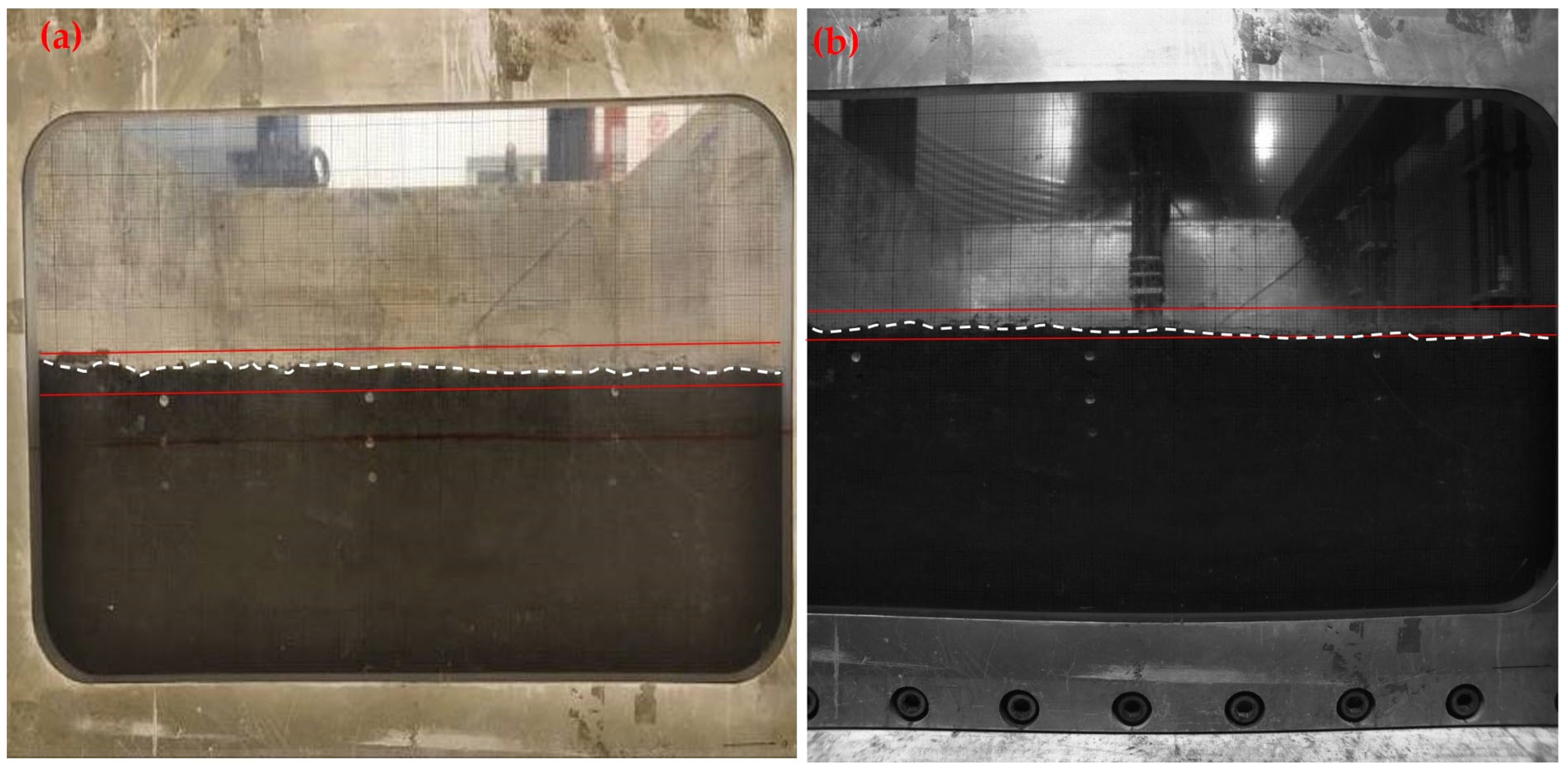

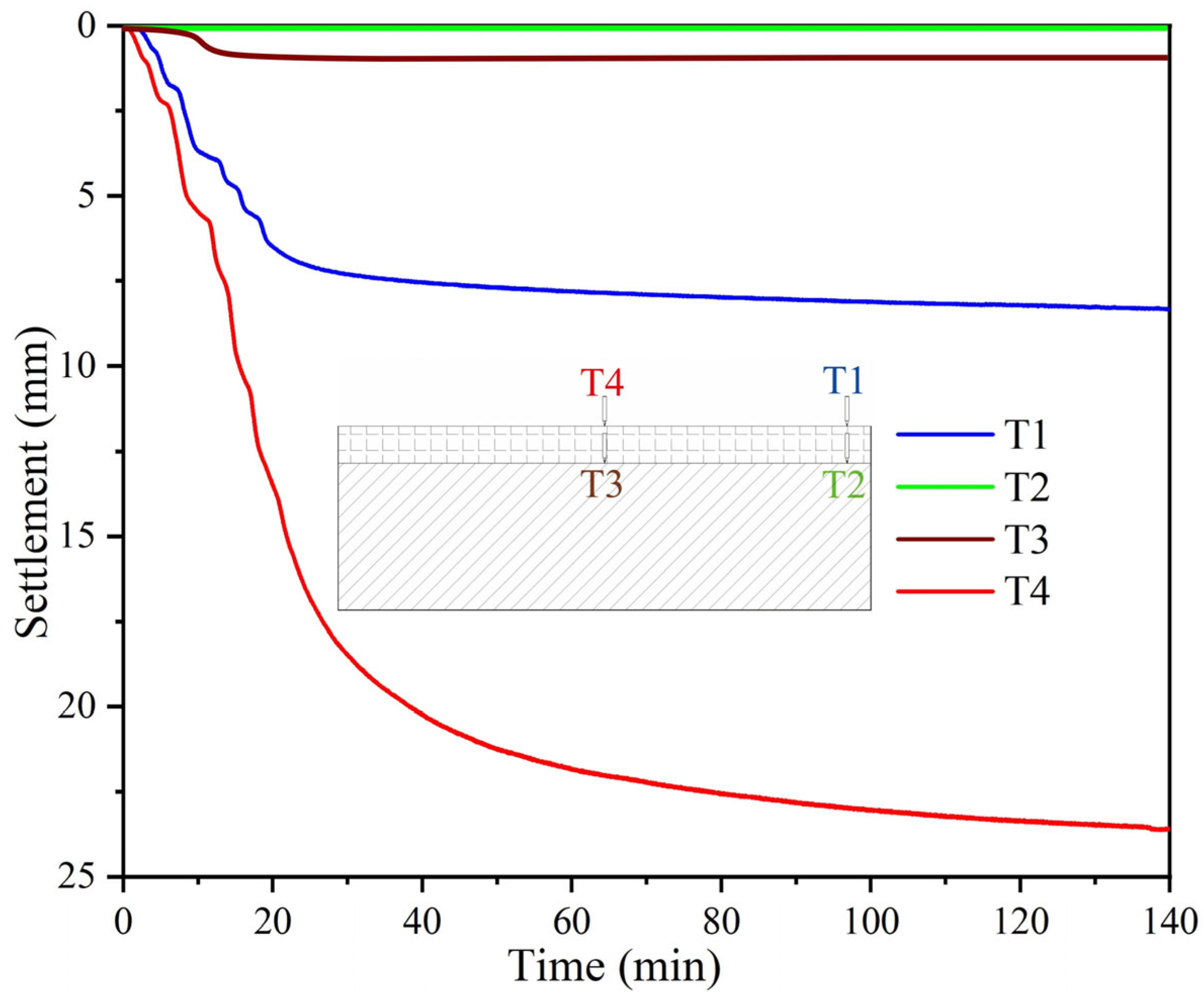

3.4. Centrifugal Test

4. Test Results and Analyses

4.1. Microstructural Characteristics

4.2. Mineral Characteristics

4.3. Pore Size Distribution

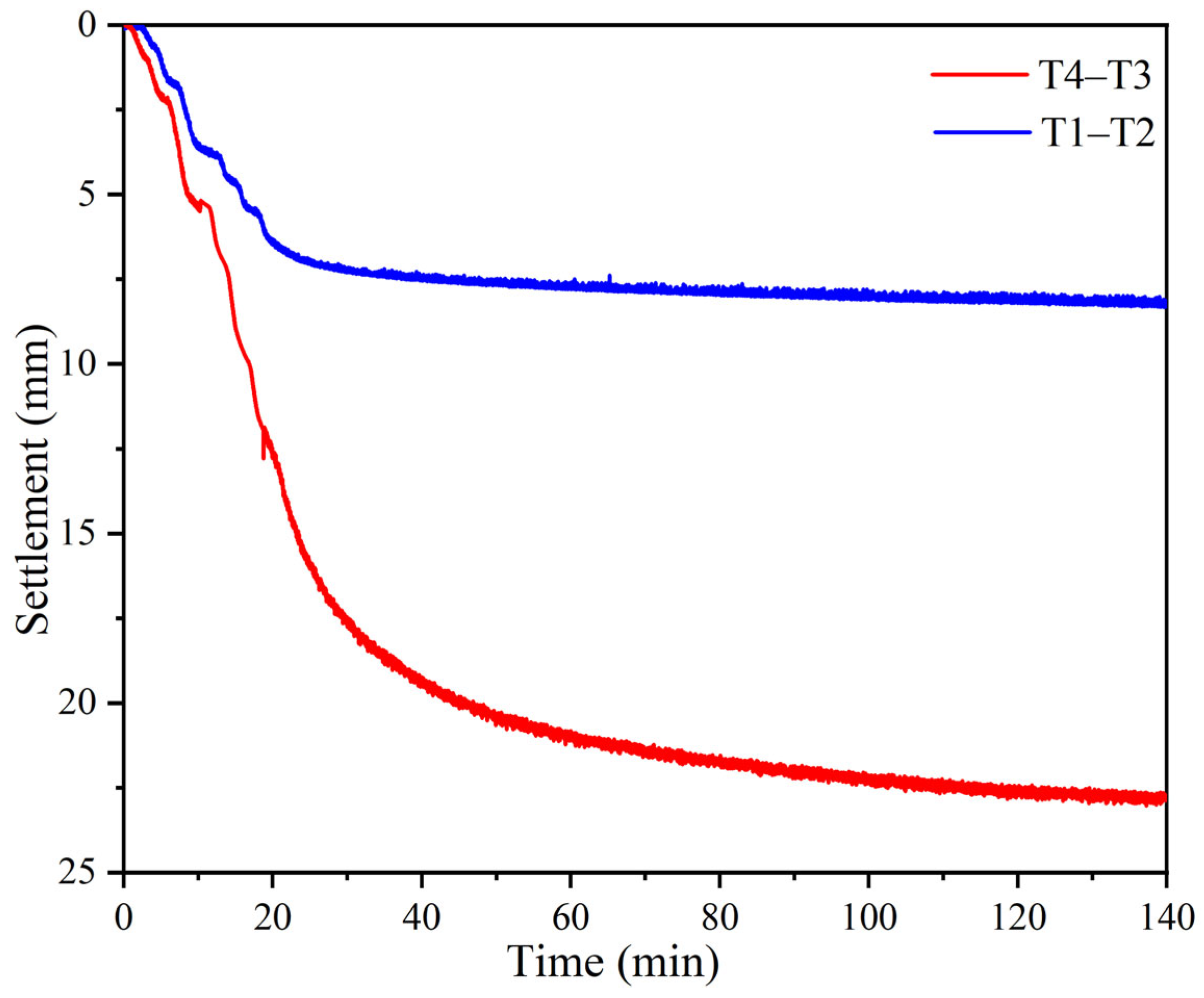

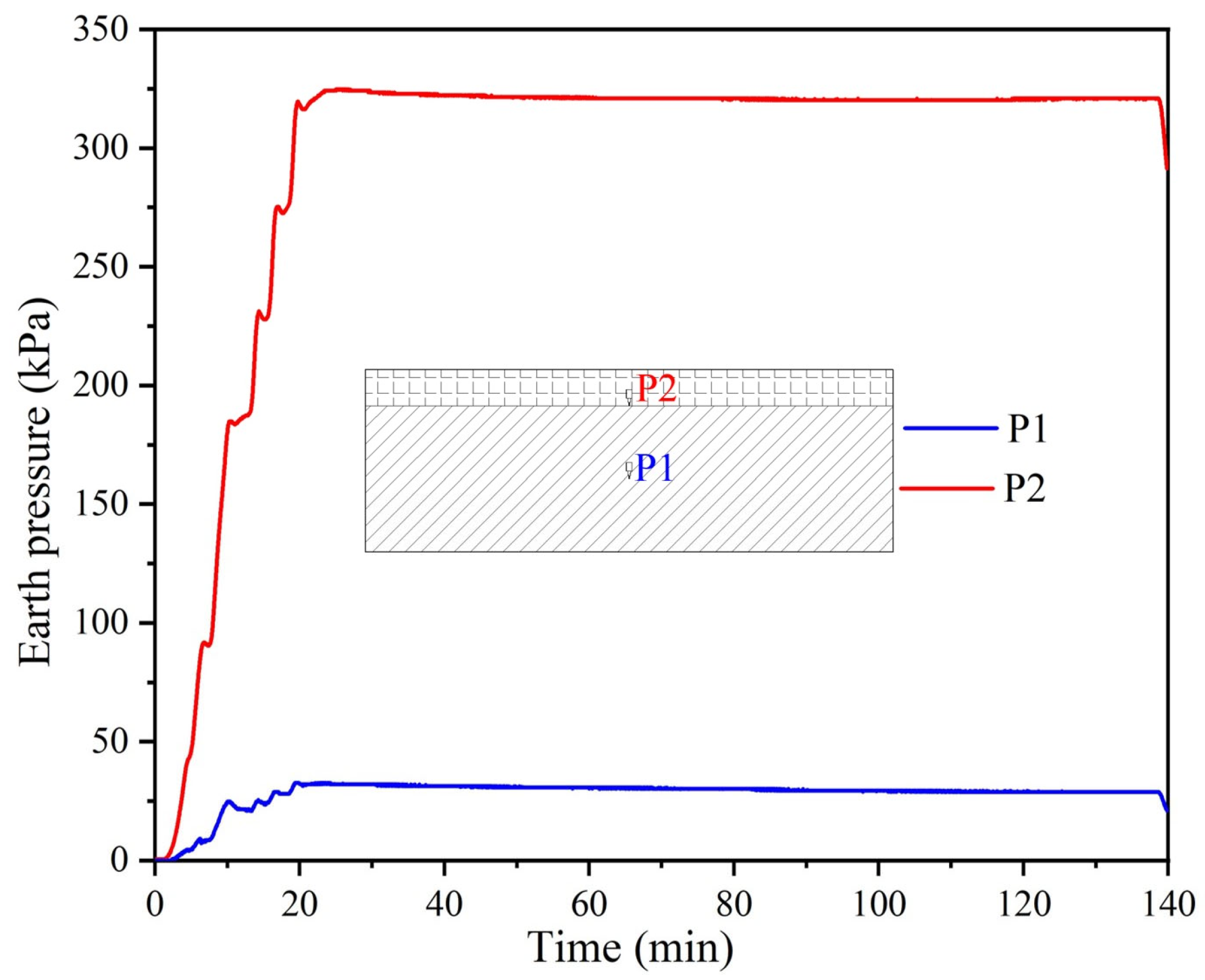

4.4. Discussion of Centrifugal Test Results

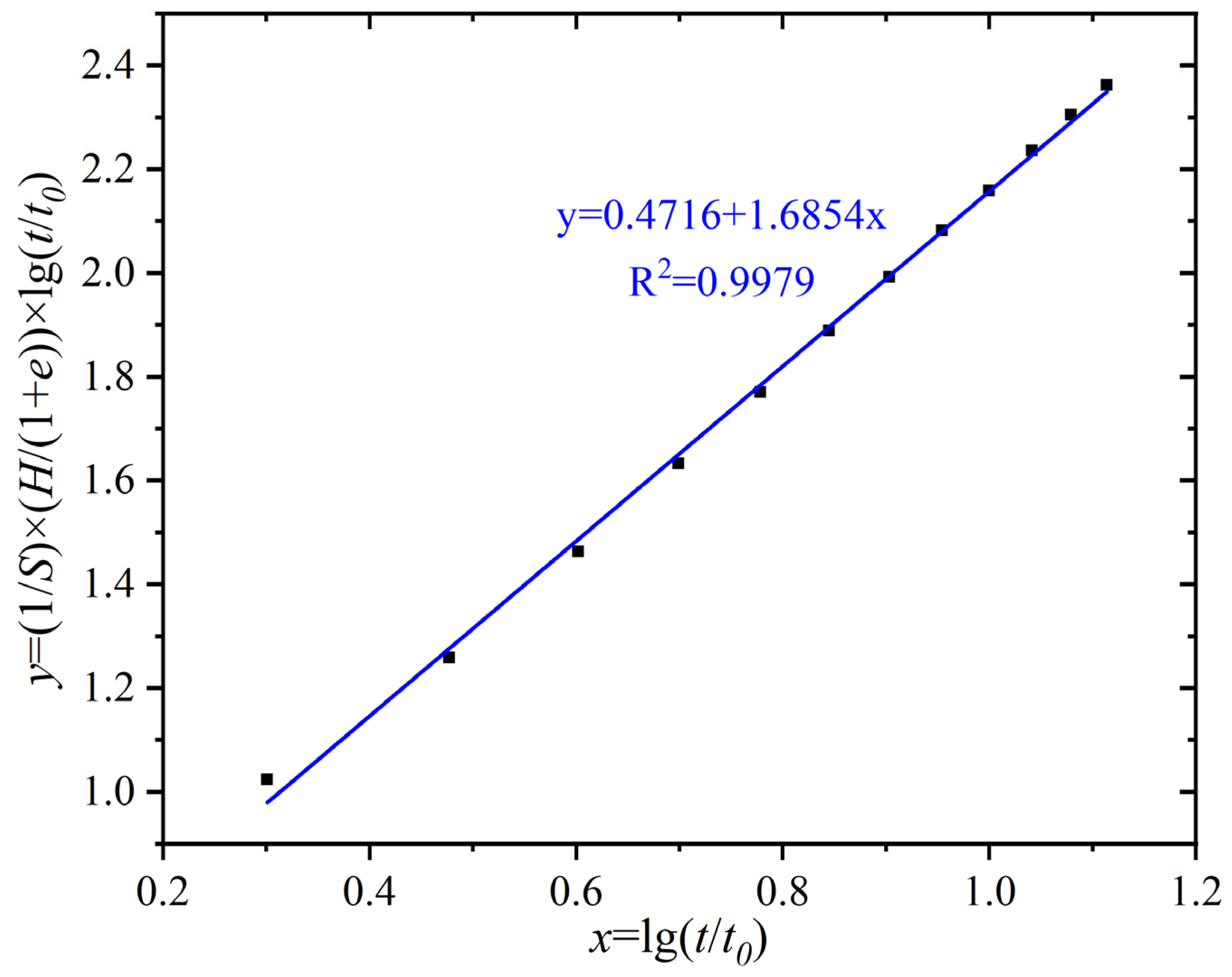

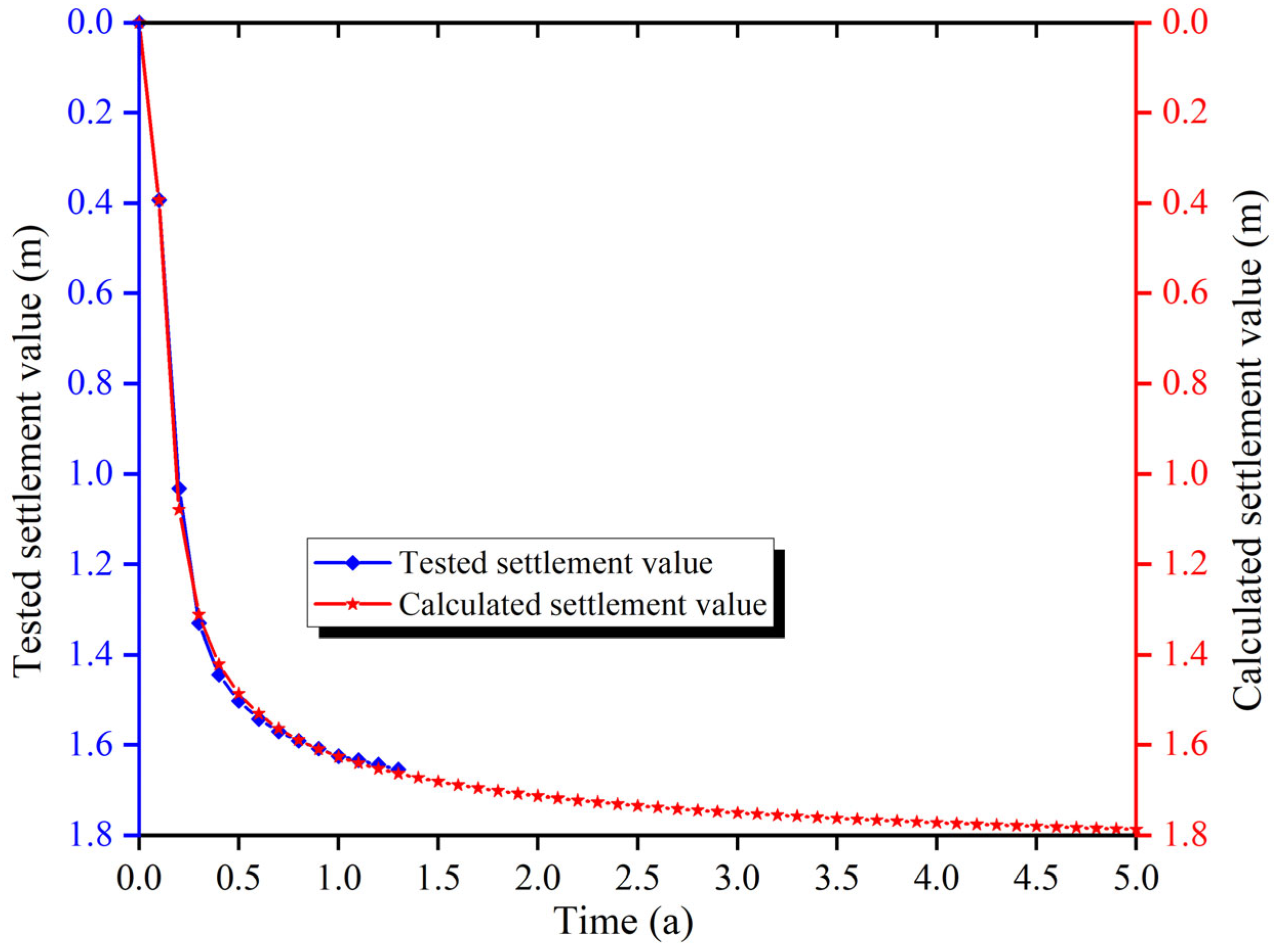

4.5. Prediction of in Situ Settlement Using Laboratory Data by Back Analyses

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The dredger fill exhibited high compressibility, elevated natural water content (22.54%), and a low dry density (1.62 g/cm3). Microstructural analysis revealed that the dredger fill exhibits a porous, flaky microstructure dominated by quartz and calcite, with mesopores (0.03–0.8 µm) accounting for over 80% of the total pore volume. These characteristics contribute to significant differential settlement under load.

- (2)

- A centrifuge modelling test conducted at 70 g acceleration simulated accelerated settlement behavior. The dredger fill layer experienced a maximum settlement of 23.62 mm (prototype-equivalent: 1.65 m), and the maximum settlement rate was 1.02 mm/min, with 70% of settlement occurs within the first year. Earth pressure measurements revealed significantly higher compressibility in the dredger fill compared to the underlying silty clay. The dredger fill layer exhibited pressures reaching 320 kPa, attributable to its higher initial void ratio, greater water content and higher compressibility.

- (3)

- A modified hyperbolic model was developed to predict long-term consolidation settlement. The model incorporates parameters derived from centrifuge test data and demonstrated strong agreement with observed settlement values over 1.3 years. The model predicts that settlement rate gradually decreased and the process was largely complete by the 4th year. The proposed prediction method offers a reliable tool for assessing long-term settlement risks in dredger fill and guiding mitigation strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asaoka, S.; Jadon, W.A.; Umehara, A.; Takeda, K.; Otani, S.; Ohno, M.; Okamura, H. Organic matter degradation characteristics of coastal marine sediments collected from the Seto Inland Sea. Mar. Chem. 2020, 225, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecuch, C.G.; Calafat, F.M.; Dangendor, S.; Jorda, G. The ability of barotropic models to simulate historical mean sea level changes from coastal tide gauge data. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 1399–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barale, V. The Asian marginal and enclosed seas: An overview. Remote Sens. Asian Seas 2019, 8, 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.F.; Zhao, L. Evaluation of the comprehensive benefit of various marine exploitation activities in China. Mar. Policy 2020, 116, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.J.; Jiang, C.C.; Wang, W.Q.; Gao, X.; Xia, Y.F. Chloride transport characteristics of concrete exposed to coastal dredger fill silty soil environment. Buildings 2023, 13, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Tome, S.; Ebid, A.M.; Usungedo, T.; Bui, V.D.; Etim, R.K.; Attah, I.C. Effect of desiccation on ashcrete (HSDA)-treated soft soil used as flexible pavement foundation: Zero carbon stabilizer approach. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaup, M.; Łozowicka, D.; Baszak, K.; Slączka, W.; Kalbarczyk-Jedynak, A. Risk analysis of seaport construction project execution. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.C.; Chien, L.K.; Chuang, S.T.; Tsai, P.C.; Hsu, Y.T.; Lu, T.T.; Lin, C.K. Stability assessment for the undersea gas pipeline. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2010, 18, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatsis, A.; Alvertos, A.; Gerolymos, N. Fragility analysis of a pipeline under slope failure-induced displacements occurring parallel to its axis. Eng. Struct. 2022, 262, 114331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; Ma, J.; Chu, J.; Fu, H.; Wang, P.; Jin, Y. Improved vacuum preloading method for consolidation of dredged clay-slurry fill. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2016, 142, 06016012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Z.G.; Ren, C. A combined method to predict the long-term settlements of roads on soft soil under cyclic traffic loadings. Acta Geotech. 2018, 13, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, J.; Thiruvenkatasamy, K.; Rao, S.N. A conceptual model of environmental geological and geo-technical response of dredged sediment fills to geo-disturbances in lowlands. Int. J. Geomate 2016, 10, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameedi, M.K.; Fattah, M.Y.; Al-omari, R.R. Creep characteristics and pore water pressure changes during loading of water storage tank on soft organic soil. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2020, 14, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yin, B.; Wang, P.; Ge, X.; Zhao, B. Pilot test and consolidation theory of marine dredged slurry using the membrane-free horizontal-vacuum method. Ocean Eng. 2024, 293, 116650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Locat, J.; Shibuya, S.; Soon, T.; Shiwakoti, D.R. Characterization of Singapore, Bangkok, and Ariake clays. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basack, S.; Purkayastha, R.D. Engineering properties of marine clays from the eastern coast of India. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2009, 1, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.T.; So, S.T.C. Geotechnical engineering properties of Hong Kong marine clays. Soft Soil Eng. 2017, 8, 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Eriktius, D.T.; Leong, E.C.; Rahardjo, H. Shear strength of peaty soil-cement mixes. Soft Soil Eng. 2017, 1, 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.H.; He, W.B. The experiment of deformation and internal force of soft pipeline caused by subsoil settlement. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 275, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Lu, Y. Responses of shallowly buried pipelines to adjacent deep excavations in Shanghai soft ground. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2018, 9, 05018002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhong, B.Y.; Yang, J.X.; Zheng, X.N.; Zhu, X.G.; Tang, Q. Numerical analysis of pipe jacking in deep soft soil based on the construction of urban underground sewage pipeline. J. Mater. Eng. Struct. 2020, 7, 639–644. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazoe, N.; Nishimura, S.; Tanaka, H.; Ogino, T.; Kochi, T. Long-term settlement behavior of peat after unloading and applicability of isotach law. Soils Found. 2025, 65, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Basu, P.; Xiong, H. Laboratory tests and thermal buckling analysis for pipes buried in Bohai soft clay. Mar. Struct. 2015, 43, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, R.; Singh, B. Time-dependent performance of large piled raft in clayey soil. Ocean Eng. 2024, 303, 117839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, N.T.; Ulusay, R.; Isik, N.S. Geo-engineering characterization and an approach to estimate the in-situ long-term settlement of a peat deposit at an industrial district. Eng. Geol. 2020, 265, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Huang, A.J.; Qin, X.G.; Zhou, S.H.; Zhou, X.L. Long-term in-situ monitoring on foundation settlement and service performance of a novel pile-plank-supported ballastless tram track in soft soil regions. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 36, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguid, M.A.; Saada, M.A.; Nunes, J.M.; Mattar, J. Physical modeling of tunnels in soft ground: A review. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2008, 23, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Cui, Z.D.; Yuan, L. Study on the long-term settlement of subway tunnel in soft soil area. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2016, 34, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.Y.; Zhao, M.Y.; Qin, C.R.; Jia, Y.J.; Wang, Z.W.; Yue, G.P. Centrifugal test of a road embankment built after new dredger fill on thick marine clay. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2020, 38, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.Z.; Ye, Y.H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.H.; Ge, F.H.; Nian, T.K. Centrifugal Test Study on the Vertical Uplift Capacity of Single-Cylinder Foundation in High-Sensitivity Marine Soil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.C.; Pi, G.L.; Ma, Z.W.; Dong, C. The reform of the natural gas industry in the PR of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 7, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H. Analysis of sustainable development of natural gas market in China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2018, 5, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F.; Chen, H.E.; Yuan, X.Q.; Shan, W.C. Analysis of the effectiveness of the step vacuum preloading method: A case study on high clay content dredger fill in Tianjin, China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampour, H. Effect of proximity of imperfections on buckle interaction in deep subsea pipelines. Mar. Struct. 2018, 59, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelalfa, H. Preloading of harbor’s quay walls to improve marine subsoilcapacity. J. Mater. Eng. Struct. 2019, 6, 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, W.C.; Yuan, X.Q.; Chen, H.E.; Li, X.L.; Li, J.F. Permeability of high clay content dredger fill treated by step vacuum preloading: Pore Distribution Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.D.; Xu, M.Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Jiang, Z.X.; Fan, Q.Q.; Liu, L.; Du, W. Pore Structure and Its Controlling Factors of Cambrian Highly Over-Mature Marine Shales in the Upper Yangtze Block, SW China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyekwena, C.C.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Alvi, I.H.; Hou, Y.; Ukaomah, C.F.; Hakuzweyezu, T. Impacts of biochar and slag on carbon sequestration potential and sustainability assessment of MgO-stabilized marine soils: Insights from MIP analysis. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1564–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, E.W. Note on a method of determining the distribution of pore sizes in a porous material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1921, 7, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihnikoutalab, M.H.; Asadi, A.; Huat, B.K.; Ball, R.J.; Singh, P. Utilisation of carbonating olivine for sustainable soil stabilisation. Environ. Geotech. 2017, 4, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Compressive strength and microstructure of soft clay soil stabilized with recycled bassanite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 104, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, K.; Dhar, A.S. Stresses in cast iron water mains subjected to non-uniform bedding and localised concentrated forces. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 12, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Shu, J.W.; Song, S.; Wu, L.X.; Ji, Y.J.; Zhai, C.Q.; Wang, J.; Lai, X.H. Advancements in drainage consolidation technology for marine soft soil improvement: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Xu, J.L.; Lu, Y.T.; Zhang, X.D.; Tran, Q.C.; Zhang, H.Q. Geotechnical properties of marine dredger fill with different particle size. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2023, 41, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisuman, A.S.K. Results of long duration settlement tests. In 1st International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering; Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 1936; pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.C.; Yao, L.N. Actual example analysis of settlement prediction during soft ground treatment. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 170, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Type | Density Water | Water Content | Dry Density | Void Ratio | Liquid Limit | Plastic Limit | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Internal Friction Angle (°) | Cohesion (kPa) | Permeability Coefficient (cm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/cm3) | (%) | (g/cm3) | (%) | (%) | ||||||

| Dredger fill | 1.97 | 22.54 | 1.62 | 0.71 | 33.64 | 21.53 | 2.8 | 8.6 | 15.3 | 3.48 × 10−5 |

| Silty clay | 2.15 | 18.41 | 1.82 | 0.48 | 26.40 | 18.9 | 5.9 | 15.4 | 24.1 | 3.32 × 10−7 |

| Soil Type | Grain Size Distribution (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.005 | 0.005–0.075 | >0.075 | |

| Dredger fill | 13.21 | 65.18 | 21.61 |

| Silty clay | 6.65 | 59.95 | 33.40 |

| Parameters | Scaling Factors |

|---|---|

| Acceleration | 70 g |

| Settlement | 1/N |

| Density | 1 |

| Consolidation coefficient | 1 |

| Stress | 1 |

| Time | 1/N2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, J.; Pei, Z.; Chen, J. Geological Characteristics and a New Simplified Method to Estimate the Long-Term Settlement of Dredger Fill in Tianjin Nangang Region. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010092

Yuan J, Pei Z, Chen J. Geological Characteristics and a New Simplified Method to Estimate the Long-Term Settlement of Dredger Fill in Tianjin Nangang Region. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010092

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Jinke, Zuan Pei, and Jie Chen. 2026. "Geological Characteristics and a New Simplified Method to Estimate the Long-Term Settlement of Dredger Fill in Tianjin Nangang Region" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010092

APA StyleYuan, J., Pei, Z., & Chen, J. (2026). Geological Characteristics and a New Simplified Method to Estimate the Long-Term Settlement of Dredger Fill in Tianjin Nangang Region. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010092