Establishment and Evaluation of an Ensemble Bias Correction Framework for the Short-Term Numerical Forecasting on Lower Atmospheric Ducts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model, Algorithms and Data

2.1. COAWST Model

2.2. Bias Correction Algorithms

2.2.1. Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN)

2.2.2. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

2.2.3. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

2.2.4. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

2.2.5. Model Output Statistics (MOS)

2.3. Bayesian Model Averaging Algorithm

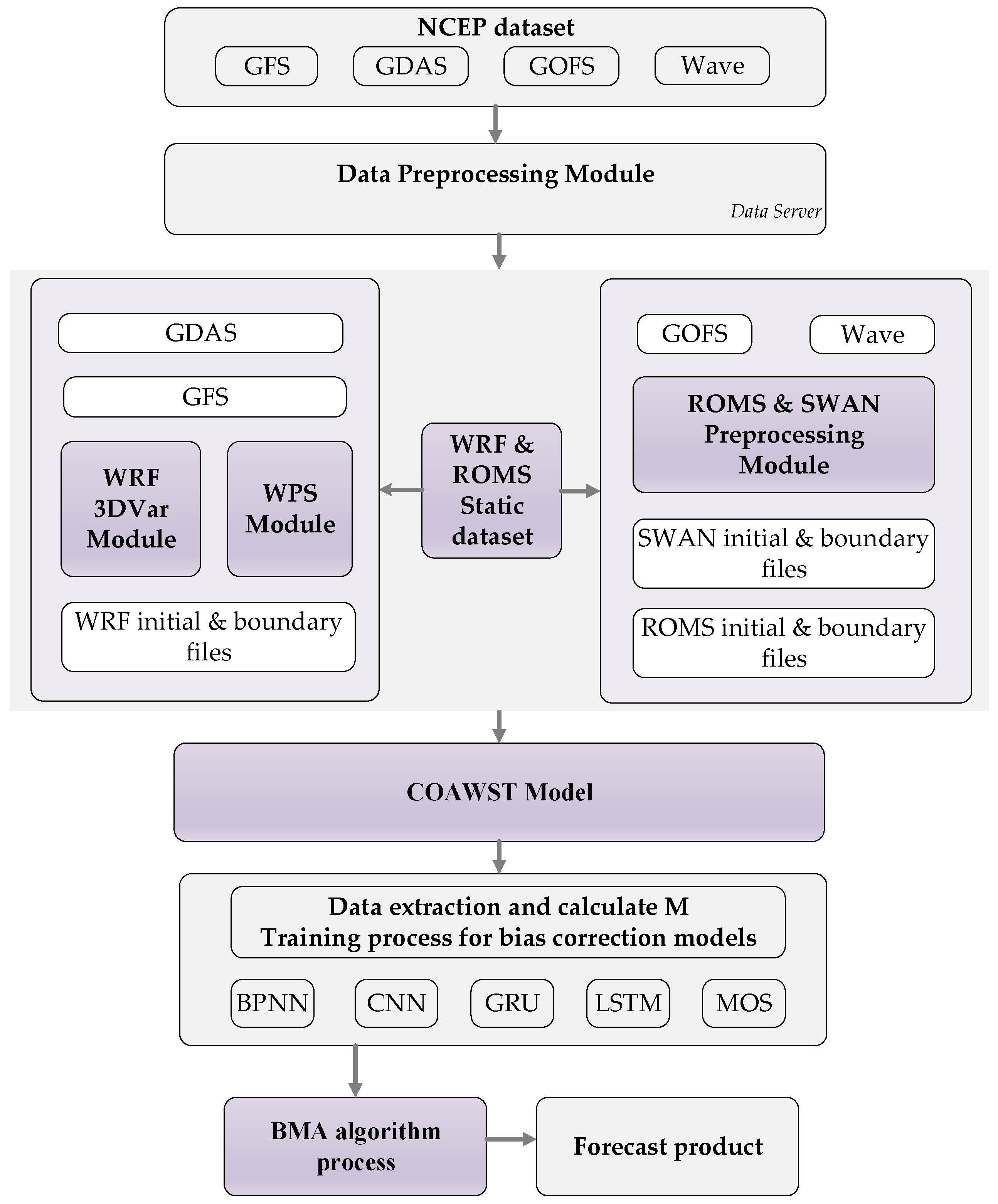

2.4. Framework for Lower Atmospheric Ducts’ Forecasting

2.5. Data Description

3. Experimental Design

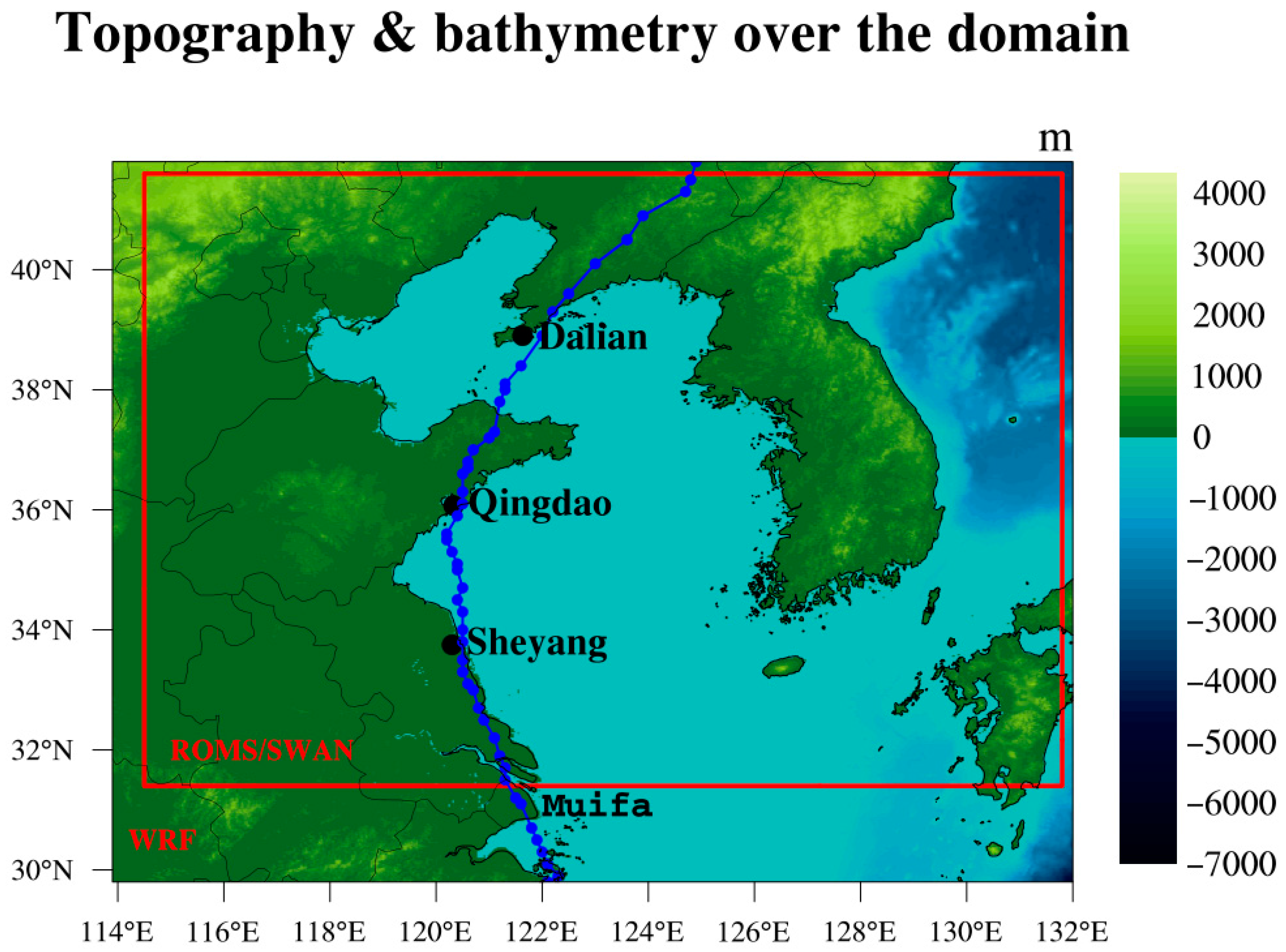

3.1. Model Configuration

3.2. Training Settings and Neural Network Architectures

3.3. Construction of Simulation Tests

4. Results

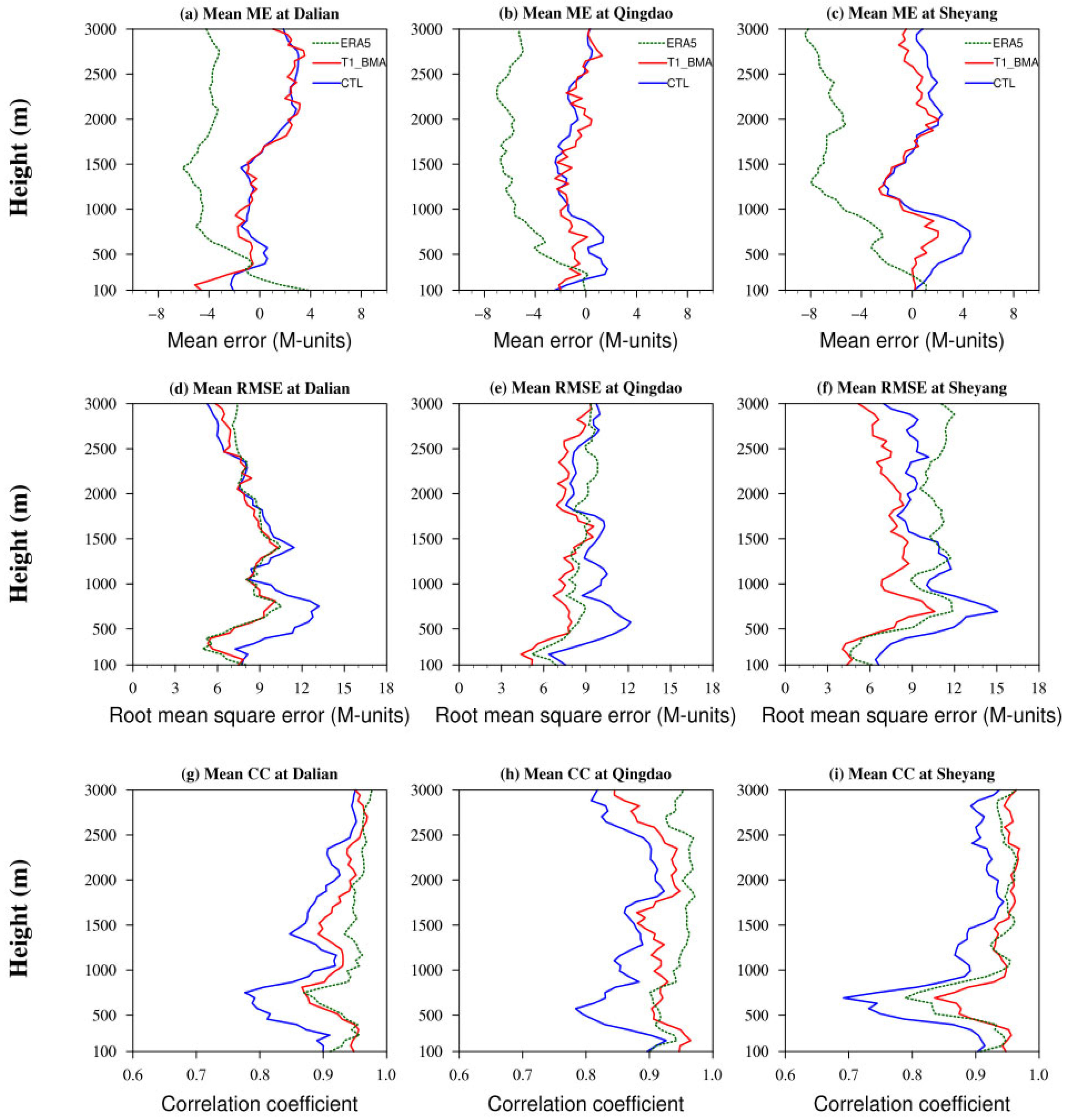

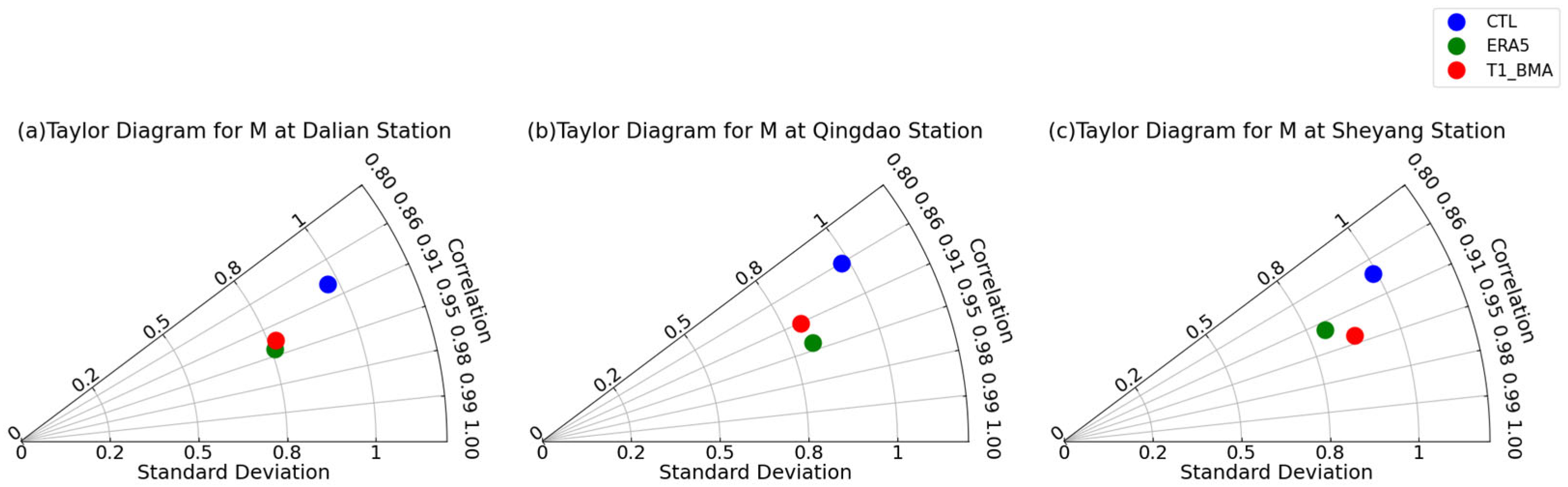

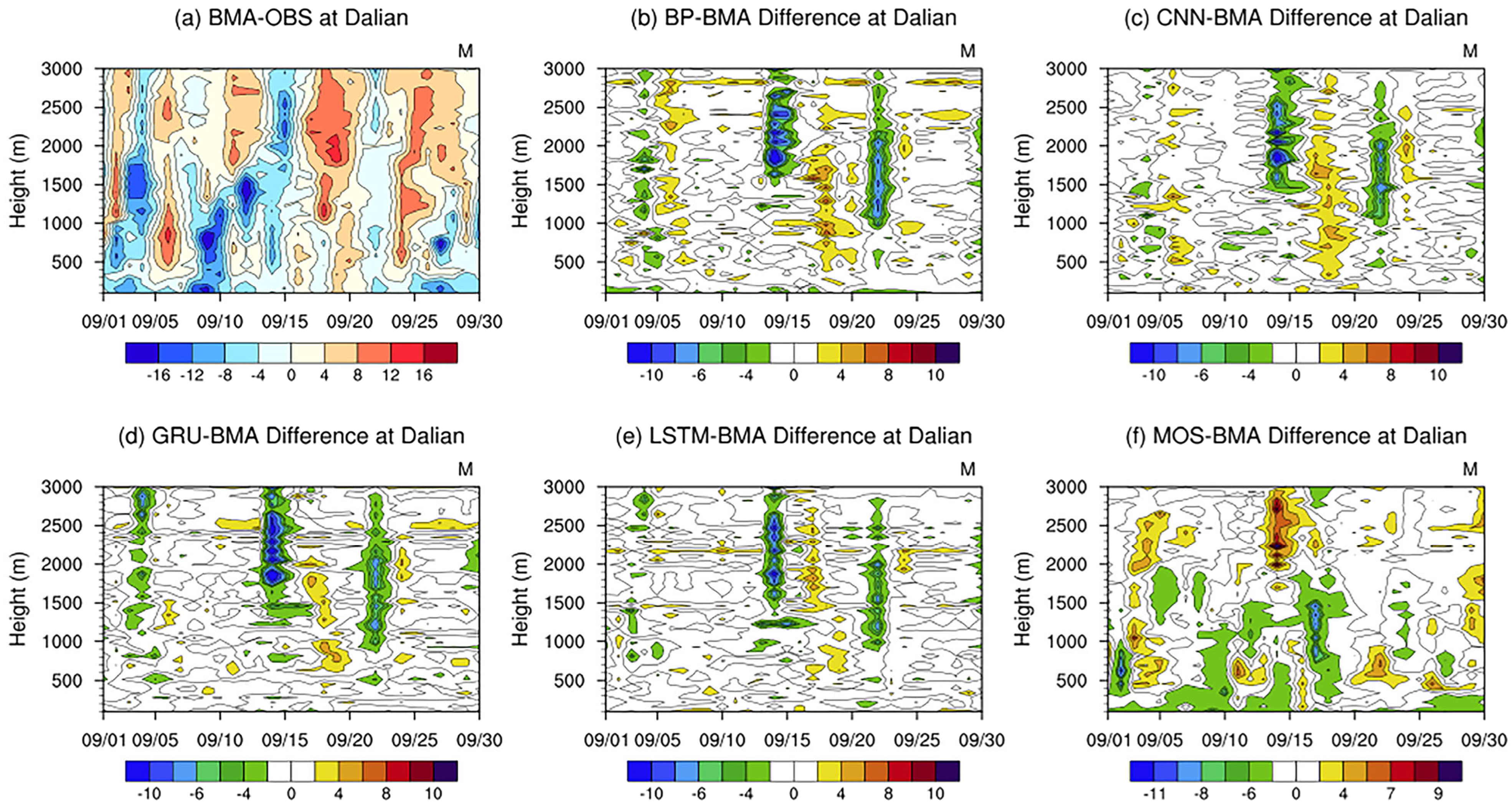

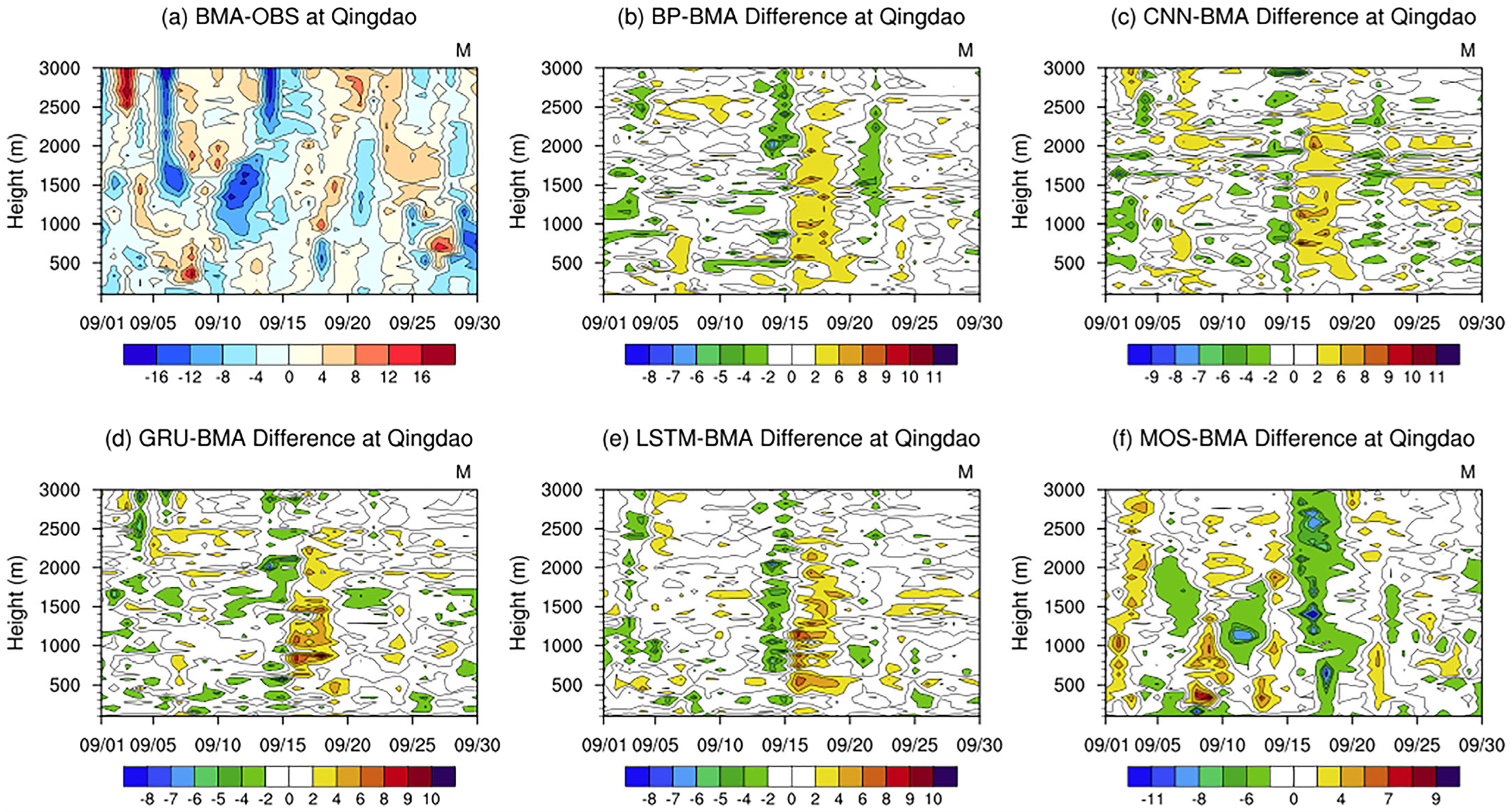

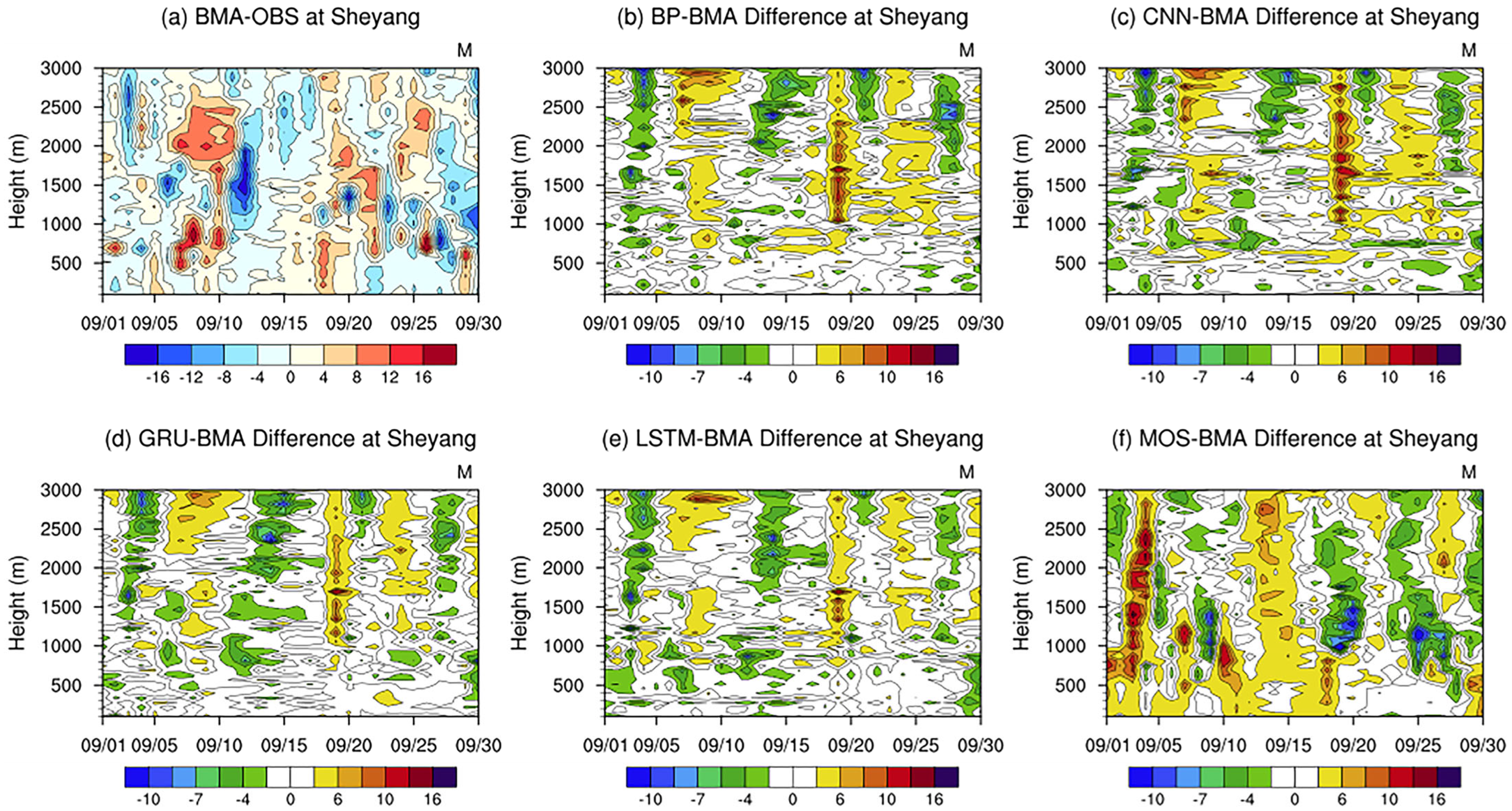

4.1. Bias Statistics of the 24 h Forecasting Result for the Modified Atmospheric Refractivity

4.2. Comparison of Accuracy Differences Between the Ensemble Forecasting and Single Algorithm Members

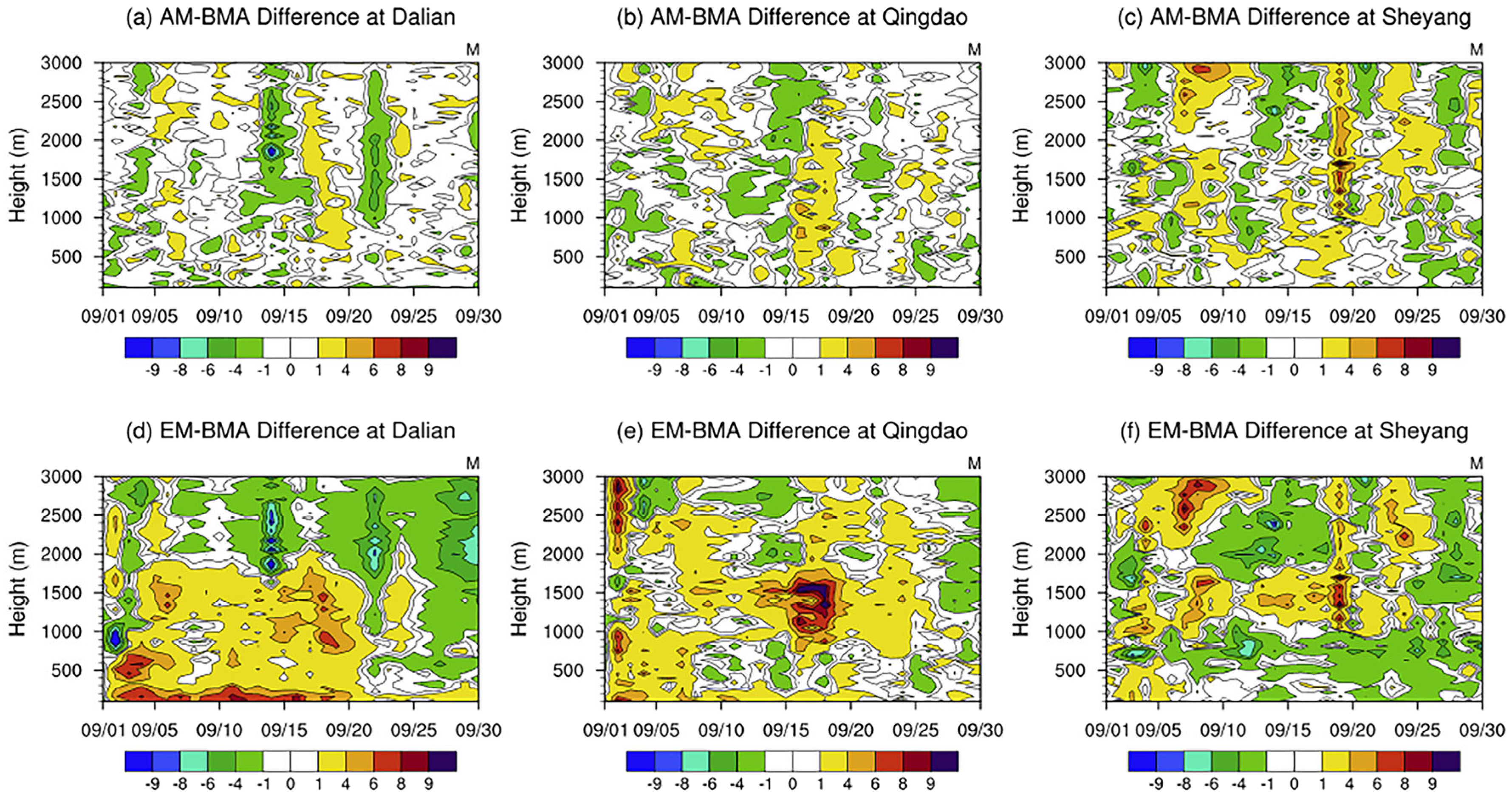

4.3. Comparison of Accuracy Differences Among Different Ensemble Methods

4.4. Bias Statistics of the 48 h and 72 h Forecasting for the Modified Atmospheric Refractivity

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Lagged response of dynamic weights: The BMA weights were updated based on a sliding window of historical performance. As a consequence, when weather regimes shifted abruptly (e.g., during the rapid passage of a cold front or typhoon), the weight distribution exhibited a lagged response and failed to adjust instantaneously to the current atmospheric state. Future work could incorporate an adaptive sliding-window strategy or a weather-regime recognition module. By dynamically adjusting the window length in response to changes in atmospheric stability, the ensemble framework could respond more rapidly to fast weather transitions.

- Variance smoothing effect: As indicated by the reduced SD in our results (see Conclusion 2), the BMA method, being a weighted-averaging approach, tended to smooth the prediction variance. While this characteristic helped reduce the RMSE, it may have underestimated extreme values or sharp gradients in the refractivity profile—features that are crucial for identifying strong ducting events. A potential improvement would be to extend the framework from deterministic forecasts to probabilistic predictions. By employing frequency-matching post-processing techniques, future systems could better preserve statistical variance and capture extreme ducting phenomena.

- Dependency on ensemble bias characteristics: The BMA method relied on the assumption that the true state lay within the spread of the ensemble members. In cases where all models systematically overestimated or underestimated the observations (e.g., due to structural deficiencies in the COAWST boundary-layer parameterization), the weighted-averaging mechanism struggled to correct the bias effectively. Therefore, enhancing the diversity of ensemble members was essential. Future research would explore integrating heterogeneous models driven by different physical parameterization schemes to expand the ensemble spread.

- As for the bias correction algorithm aspect, regarding the selection of bias correction algorithms, this study primarily employed classical deep learning models (e.g., CNN, LSTM). To rigorously justify the computational cost associated with these complex algorithms, we conducted additional comparative tests using traditional statistical models, specifically ARIMA and Linear Regression (LR), as benchmarks (see Table 3). The results indicated that the deep learning-based methods consistently outperformed these simpler statistical models in terms of RMSE and CCs, confirming that their ability to capture non-linear error patterns justified the increased complexity. However, even the advanced deep learning models did not yield optimal performance across all weather scenarios, as their accuracy largely depended on the specific feature-capturing capabilities and training strategies. This inconsistency reinforced the necessity of the dynamic ensemble weighting strategy (BMA) adopted in this study to mitigate algorithmic uncertainty. Future work will focus on two aspects to further enhance model performance: first, exploring state-of-the-art architectures such as Transformer networks and attention mechanisms, which have shown superior potential in handling long-term dependencies compared to RNNs, and second, optimizing the training strategy by incorporating advanced data preprocessing techniques. Previous studies demonstrated that applying data clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and other feature extraction methods can significantly improve model robustness, an aspect not yet addressed in the present study but planned for future investigation.

- 2.

- As for the result aspect, the validation data used in this study also had representativeness limitations. Because the ERA5 data with certain biases was not suitable as the evaluation reference in this study, only radiosonde observation data from three stations were selected for the verification of atmospheric duct characteristics, and the choice of stations was somewhat random. Furthermore, the radiosonde observation data were available only twice daily and occasionally contained missing values, highlighting the need for collecting denser and more continuous observations for future validation and assessment. In addition, this study used only the modified atmospheric refractivity series output from the COAWST model as input to the neural networks, without incorporating fundamental meteorological variables such as air temperature, air pressure, and humidity. This represented an underutilization of the COAWST model’s available information. Atmospheric ducts are physically driven by vertical gradients of temperature and humidity. By excluding these available meteorological variables and relying solely on univariate error history, the machine learning models essentially performed advanced signal smoothing rather than learning the physical error correlations, which limited the intelligence of the bias correction. Future studies will consider developing a multidimensional feature framework that includes complete meteorological fields (e.g., temperature profiles, pressure fields, humidity fields, and wind fields) and integrating physical constraints into the neural network construction process, with the goal of enhancing the model’s physical interpretability while maintaining strong statistical performance.

- 3.

- As for the experimental design aspect, the training period (January 2016 to December 2021) and validation period (September 2022) were not consecutive. However, this design was driven by specific scientific considerations. First, to rigorously test the model’s generalization capability, this study intentionally selected a “future” and “unseen” period distinct from the training set, rather than using random cross-validation. This approach cuts off the temporal “memory” inherent in meteorological data, thereby simulating a realistic operational forecasting scenario where the model must perform without prior knowledge. Second, the selection of September 2022 as this period featured the rare passage of Typhoon Muifa, which passed the study domain from south to north, providing a unique opportunity to evaluate error performance under extreme atmospheric perturbations. Additionally, as a seasonal transition period characterized by the retreat of the East Asian summer monsoon and alternating cold/warm fronts, September represents a critical window for atmospheric duct formation. Third, although the duration was short, the experiment involved daily rolling forecasts for the next 72 h, generating a substantial volume of hourly evaluation points equivalent to three months of data. Nevertheless, the one-month duration is not sufficient enough to comprehensively evaluate the model’s long-term applicability across different seasonal patterns and inter-annual variations. Future work will prioritize conducting longer-term and continuous forecasting tests to further verify the robustness and optimize the performance of the proposed framework.

- During the validation period in September 2022, comparison with radiosonde observation data at the Dalian, Qingdao, and Sheyang stations showed that the COAWST model exhibited relatively high RMSEs of the modified atmospheric refractivity forecasting below 1000 m, with the overall bias decreased with increasing altitude. After applying the BMA-based ensemble bias correction, the forecasting result of modified atmospheric refractivity outperformed the original COAWST model forecasting in terms of RMSE, ME, and CC. In addition, the RMSE of the BMA-corrected forecasting was lower than that of the ERA5 data, although the CC was slightly lower.

- After BMA-based ensemble bias correction, the CC between the forecasting result and radiosonde observation data increased by 0.04, 0.05, and 0.06, respectively. However, the SD of the corrected forecasting was lower than that of the original model, which was consistent with previous studies, indicating that the BMA-based ensemble bias correction reduced the variability of the forecasting series to some extent.

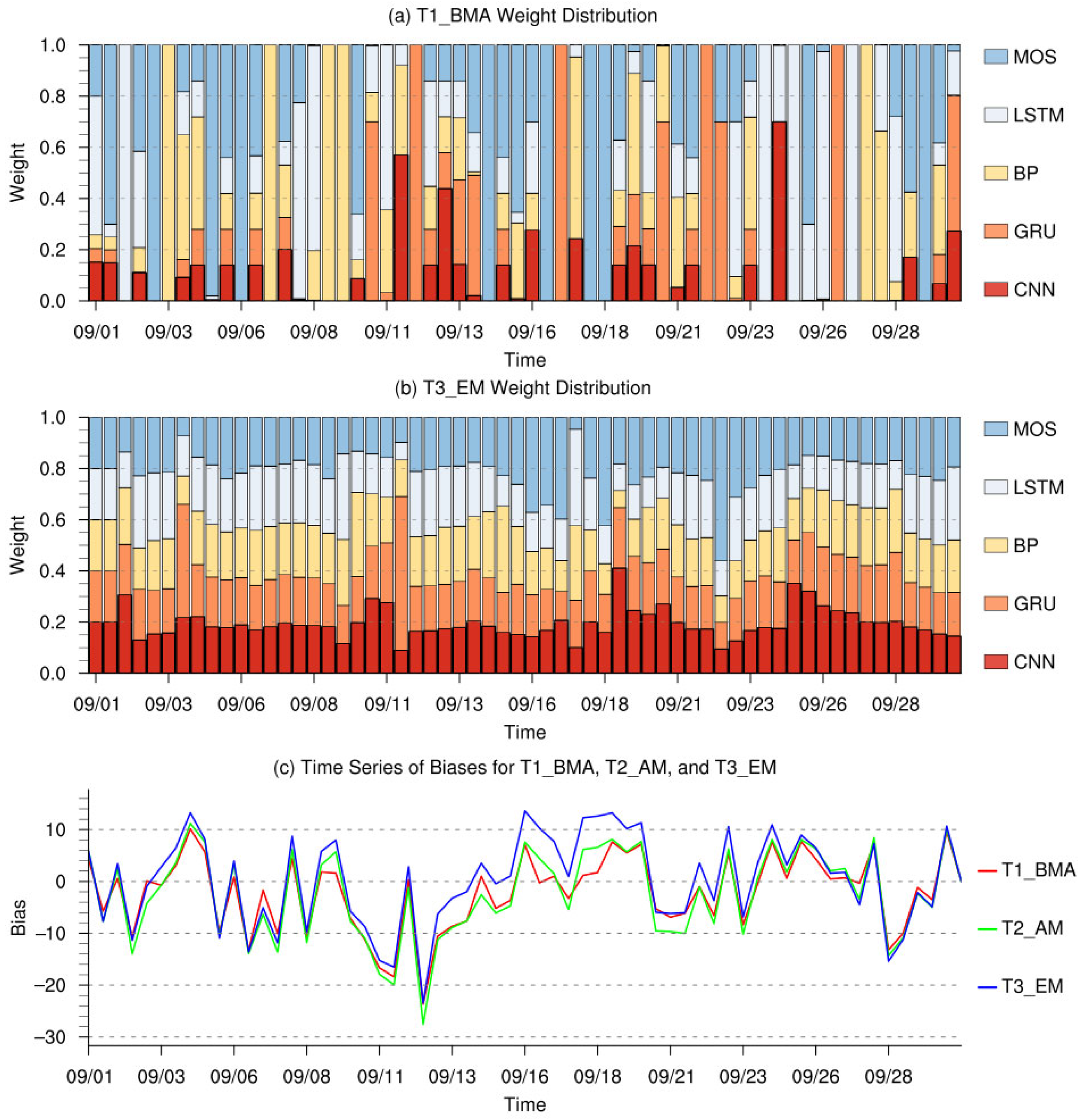

- Regarding the differences among ensemble members, the four neural-network-based algorithm members exhibited varying degrees of systematic bias during the typhoon passage. On average, the T1_LSTM test showed the lowest overall biases. The unique diversity of the T1_MOS test played a compensatory role within the ensemble, effectively reducing the uncertainty of the BMA-based ensemble method.

- In terms of the performance of different ensemble methods, the arithmetic average (T2_AM) test and variable-weight ensemble averaging (T3_EM) method failed to capture nonlinear bias characteristics under extreme conditions, resulting in lower forecasting accuracy than the T1_BMA test. This finding further confirmed that the BMA-based ensemble method, through Bayesian optimization, effectively achieved adaptive weight allocation, allowing it to balance the contributions of single models more accurately under complex weather conditions.

- From the perspective of different forecasting result lead times, the T1_BMA test effectively reduced both systematic and random biases and improved correlations with radiosonde observation data in the 72-h forecasting. These results indicated that the ensemble bias correction model developed in this study was able to maintain high stability and adaptability in short-term forecasting applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COAWST | Coupled Ocean–Atmosphere–Wave–Sediment Transport |

| BMA | Bayesian Model Averaging |

| ME | Mean Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| CC | Correlation Coefficient |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| RKHS | Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space |

| EnKF | Ensemble Kalman Filter |

| SPCAM | Super Parameterized Community Atmosphere Model |

| NNCAM | Neural Network version of Community Atmosphere Model |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast |

| IFS | Integrated Forecasting System |

| ANO | Anomaly Numerical-correction with Observations |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting |

| Bi-LSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| TrajGRU | Trajectory Gated Recurrent Unit |

| RE | Relative Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ERA5 | ECMWF Reanalysis v5 |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| BP | Backpropagation Neural Network |

| MOS | Model Output Statistics |

| ROMS | Regional Ocean Modeling System |

| SWAN | Simulating Waves Nearshore |

| MCT | Model Coupling Toolkit |

| 1-D CNN | One-dimensional convolutional neural network |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| WSM6 | WRF Single-Moment 6-Class |

| MM5 | The fifth-Generation Penn State/NCAR Mesoscale Model |

| RRTM | Rapid Radiative Transfer Model |

| Noah-LSM | Noah Land Surface Model |

| GF | Grell–Freitas |

| GFS | Global Forecast System |

| RTOFS | Real Time Ocean Forecast System |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| NCEP | National Centers for Environmental Prediction |

| GDAS | Global Data Assimilation System |

| GOFS | Global Ocean Forecasting System |

| Probability Density Function | |

| WRF-3DVar | Three-Dimensional Variational Assimilation Module |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| WPS | WRF Preprocessing System |

| M | Modified Atmospheric Refractivity |

| N | Refractivity |

| T | Air Temperature |

| P | Air Pressure |

| e | Water Vapor Pressure |

| q | Specific Humidity |

| ε | 0.622 |

| H | Altitude |

| y | Forecasting Variable |

| f | Bias-correction Model Space |

| K | Number of Models |

| D | Observation Dataset |

| Conditional PDF of the Forecasting Variable | |

| Posterior Probability of the kth Model | |

| Marginal or Integrated Likelihood of Each Model | |

| Parameter Vector of Model | |

| Variance | |

| Expected Value | |

| Mens,dt | Ensemble Forecasting for Day d at Time t |

| Od−1 | Observations on the Previous Day d − 1 |

| i | Forecasting Member ID |

| N | Total Number of Forecasting Members |

| αi,d | Weight of Model Mi on Day d |

| E | Reciprocal of the RMSE |

References

- Wang, H.; Su, S.; Tang, H.; Jiao, L.; Li, Y. Atmospheric Duct Detection Using Wind Profiler Radar and RASS. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2019, 36, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.T.; Haack, T. An Investigation of Sea Surface Temperature Influence on Microwave Refractivity: The Wallops-2000 Experiment. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2011, 50, 2319–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, S.M.; Young, G.S.; Carton, J.A. A New Model of the Oceanic Evaporation Duct. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1997, 36, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, E.; Akan, O. Beyond-Line-of-Sight Communications with Ducting Layer. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, E.; Akan, O.B. Channel Model for the Surface Ducts: Large-Scale Path-Loss, Delay Spread, and AOA. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 2015, 63, 2728–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Kang, S. Research status and thinking of atmospheric duct. Chin. J. Radio Sci. 2020, 35, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, K.A. Statistical Theory and Methodology in Science and Engineering; John Wiley Sons Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Zhao, B.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Du, J.; Dai, F. The analysis on characteristic of atmospheric duct and its effects on the propagation of electromagnetic wave. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2000, 58, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Hu, Z.; Hartnett, M. Short-Term Forecasting of Coastal Surface Currents Using High Frequency Radar Data and Artificial Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yang, H.; Kim, J. Sea Surface Temperature and High Water Temperature Occurrence Prediction Using a Long Short-Term Memory Model. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.; Harlim, J. Correcting Biased Observation Model Error in Data Assimilation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2017, 145, 2833–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasp, S.; Pritchard, M.S.; Gentine, P. Deep Learning to Represent Subgrid Processes in Climate Models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9684–9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Chen, M.; Chen, K.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, B.; Song, L.; Qin, R. A Deep Learning Method for Bias Correction of ECMWF 24–240 h Forecasts. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 1444–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Ye, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X. Bias Correction of the Hourly Satellite Precipitation Product Using Machine Learning Methods Enhanced with High-Resolution WRF Meteorological Simulations. Atmos. Res. 2024, 310, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dong, J.; Song, X.; Gao, Z.; Pang, R.; Guoan, B. A Deep-Learning Real-Time Bias Correction Method for Significant Wave Height Forecasts in the Western North Pacific. Ocean Modell. 2024, 187, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Combination of Multiple Data-Driven Models for Long-Term Monthly Runoff Predictions Based on Bayesian Model Averaging. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 3321–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasp, S.; Lerch, S. Neural Networks for Postprocessing Ensemble Weather Forecasts. Mon. Weather Rev. 2018, 146, 3885–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutbecher, M.; Palmer, T.N. Ensemble Forecasting. J. Comput. Phys. 2008, 227, 3515–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, I.; Khan, M.; Abraham, A. An Ensemble of Neural Networks for Weather Forecasting. Neural Comput. Appl. 2004, 13, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean Sloughter, J.; Gneiting, T.; Raftery, A.E. Probabilistic Wind Vector Forecasting Using Ensembles and Bayesian Model Averaging. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 2107–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achite, M.; Banadkooki, F.B.; Ehteram, M.; Bouharira, A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Elshafie, A. Exploring Bayesian Model Averaging with Multiple ANNs for Meteorological Drought Forecasts. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 1835–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Ajami, N.K.; Gao, X.; Sorooshian, S. Multi-Model Ensemble Hydrologic Prediction Using Bayesian Model Averaging. Adv. Water Resour. 2007, 30, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Han, H.; Shu, Z. Bayesian Model Averaging by Combining Deep Learning Models to Improve Lake Water Level Prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Hu, T.; Wang, B.; Li, Z. Development of a Numerical Prediction Model for Marine Lower Atmospheric Ducts and Its Evaluation across the South China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Yu, K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, J. High Resolution Regional Climate Simulation over CORDEX East Asia Phase II Domain Using the COAWST Ocean-Atmosphere Coupled Model. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 8711–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.C.; Armstrong, B.; He, R.; Zambon, J.B. Development of a Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere-Wave-Sediment Transport (COAWST) Modeling System. Ocean Modell. 2010, 35, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, C.; Raskar, S.D.; Tambe, S.S.; Kulkarni, B.D.; Keshavamurty, R.N. Prediction of All India Summer Monsoon Rainfall Using Error-Back-Propagation Neural Networks. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 1997, 62, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-L. Back-Propagation Neural Network for the Prediction of the Short-Term Storm Surge in Taichung Harbor, Taiwan. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2008, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-L. Back-Propagation Neural Network for Long-Term Tidal Predictions. Ocean Eng. 2004, 31, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, T.; Kiranyaz, S.; Eren, L.; Askar, M.; Gabbouj, M. Real-Time Motor Fault Detection by 1-D Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 7067–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; van Merrienboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations Using RNN Encoder-Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Kumar, S.; Basu, M. A Gated Recurrent Unit Approach to Bitcoin Price Prediction. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Ma, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, P. A Deep Neural Network Model for Short-Term Load Forecast Based on Long Short-Term Memory Network and Convolutional Neural Network. Energies 2018, 11, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glahn, H.R.; Lowry, D.A. The Use of Model Output Statistics (MOS) in Objective Weather Forecasting. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1972, 11, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftery, A.E.; Gneiting, T.; Balabdaoui, F.; Polakowski, M. Using Bayesian Model Averaging to Calibrate Forecast Ensembles. Mon. Weather Rev. 2005, 133, 1155–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, W.E. Note on the Use of the Inverse Gaussian Distribution for Wind Energy Applications. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1980, 19, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Xia, J.; Fisher, J.B.; Dong, W.; Zhang, X.; Liang, S.; Ye, A.; Cai, W.; Feng, J. Using Bayesian Model Averaging to Estimate Terrestrial Evapotranspiration in China. J. Hydrol. 2015, 528, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.L.; Qin, Q. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 2022, 9, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shi, J. Application of Bayesian Model Averaging in Modeling Long-Term Wind Speed Distributions. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S.; Dracup, J.A. Stochastic Parameter Estimation Procedures for Hydrologie Rainfall-runoff Models: Correlated and Heteroscedastic Error Cases. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.; Ahn, J.; Ji, S. An Effective Optimization Method for Machine Learning Based on ADAM. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Rosasco, L.; Caponnetto, A. On Early Stopping in Gradient Descent Learning. Constr. Approx. 2007, 26, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, T.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, B.; Cui, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, T.; Guo, Y. Development and Evaluation of a Short-Term Ensemble Forecasting Model on Sea Surface Wind and Waves across the Bohai and Yellow Sea. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, T.; Wang, C.; Garrett, S.; Glazer, A.; Mailhot, J.; Marshall, R. Mesoscale Modeling of Boundary Layer Refractivity and Atmospheric Ducting. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 2437–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station | T1_BMA | T2_AM | T3_EM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | RMSE | CC | ME | RMSE | CC | ME | RMSE | CC | |

| Dalian | 0.28 M | 7.51 M | 0.99 | 0.38 M | 8.27 M | 0.98 | 0.48 M | 8.29 M | 0.98 |

| Qingdao | −0.14 M | 7.15 M | 0.99 | −0.84 M | 7.94 M | 0.98 | 0.82 M | 8.22 M | 0.99 |

| Sheyang | 0.03 M | 6.82 M | 0.99 | 0.25 M | 7.95 M | 0.99 | −0.14 M | 8.21 M | 0.99 |

| Station | Forecasting Lead Time | CTL | T1_BMA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | RMSE | CC | ME | RMSE | CC | ||

| Dalian | 48 h ahead | 1.99 M | 11.34 M | 0.83 | 0.94 M | 8.91 M | 0.90 |

| 72 h ahead | 1.55 M | 11.69 M | 0.81 | 0.65 M | 9.09 M | 0.89 | |

| Qingdao | 48 h ahead | 0.20 M | 11.48 M | 0.82 | −0.44 M | 8.42 M | 0.89 |

| 72 h ahead | 0.20 M | 13.50 M | 0.76 | 0.39 M | 9.34 M | 0.87 | |

| Sheyang | 48 h ahead | 3.78 M | 15.19 M | 0.77 | 1.46 M | 9.86 M | 0.89 |

| 72 h ahead | 1.05 M | 16.03 M | 0.71 | 0.26 M | 10.73 M | 0.87 | |

| Indices | Forecasting Lead Time | Station | BP | CNN | GRU | LSTM | MOS | LR | ARIMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 24 h ahead | Dalian | 9.02 M | 9.44 M | 9.01 M | 8.19 M | 9.25 M | 9.24 M | 8.81 M |

| Qingdao | 8.30 M | 8.90 M | 8.74 M | 7.74 M | 9.19 M | 9.25 M | 9.19 M | ||

| Sheyang | 8.55 M | 8.82 M | 8.51 M | 7.88 M | 9.57 M | 9.70 M | 9.67 M | ||

| CC | 24 h ahead | Dalian | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Qingdao | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | ||

| Sheyang | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Wang, B.; Zou, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, B.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. Establishment and Evaluation of an Ensemble Bias Correction Framework for the Short-Term Numerical Forecasting on Lower Atmospheric Ducts. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122397

Guo H, Wang B, Zou J, Zhao X, Wang B, Qiu Z, Wang H, Liu L, Liu X, Wang H. Establishment and Evaluation of an Ensemble Bias Correction Framework for the Short-Term Numerical Forecasting on Lower Atmospheric Ducts. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122397

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Huan, Bo Wang, Jing Zou, Xiaofeng Zhao, Bin Wang, Zhijin Qiu, Hang Wang, Lu Liu, Xiaolei Liu, and Hanyue Wang. 2025. "Establishment and Evaluation of an Ensemble Bias Correction Framework for the Short-Term Numerical Forecasting on Lower Atmospheric Ducts" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122397

APA StyleGuo, H., Wang, B., Zou, J., Zhao, X., Wang, B., Qiu, Z., Wang, H., Liu, L., Liu, X., & Wang, H. (2025). Establishment and Evaluation of an Ensemble Bias Correction Framework for the Short-Term Numerical Forecasting on Lower Atmospheric Ducts. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122397