Effect of Fine Content on Liquefaction Resistance of Saturated Marine Sandy Soils Subjected to Cyclic Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

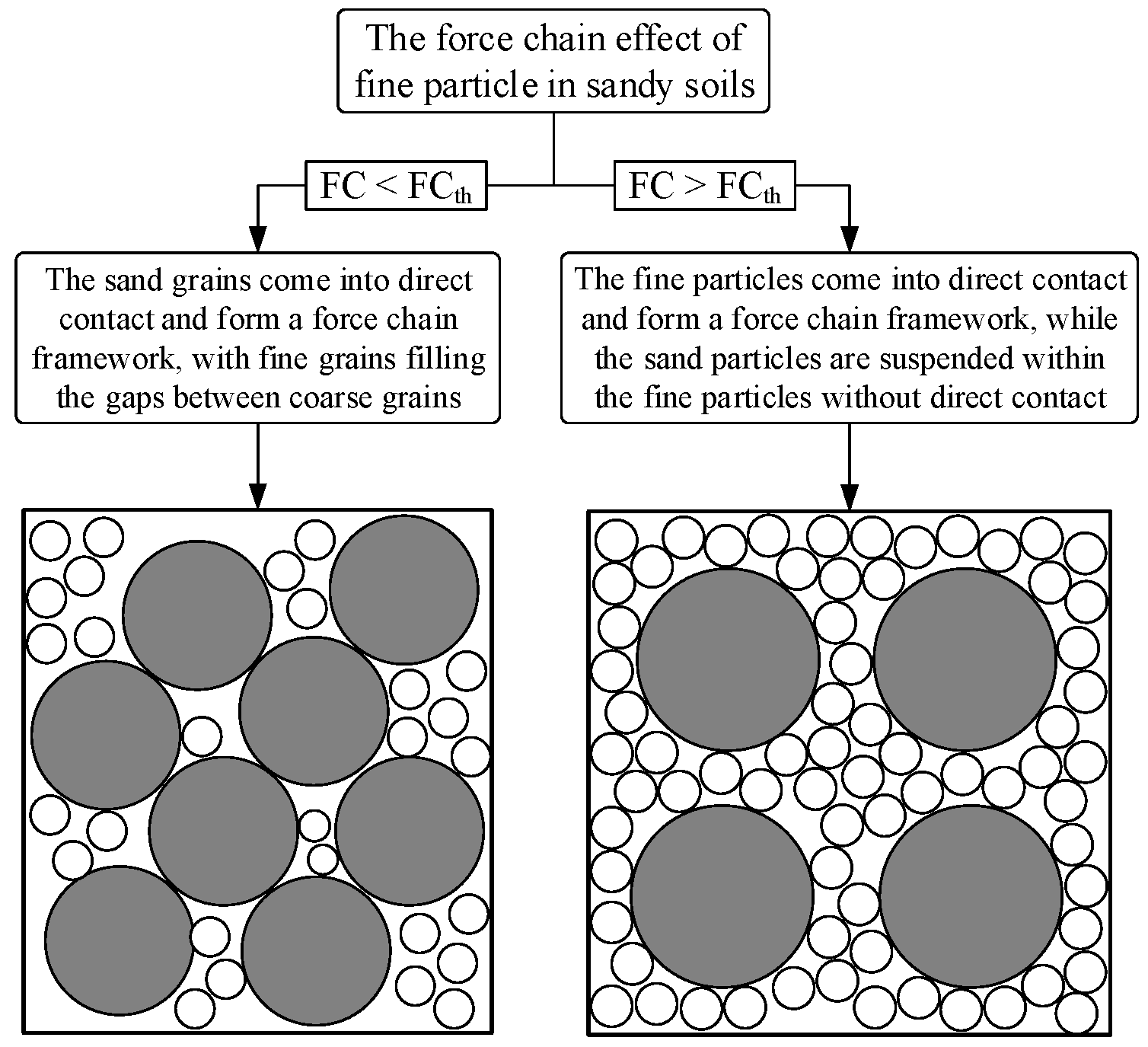

2. The Particle Contact State of Sandy Soils

3. Undrained Cyclic Triaxial Test

3.1. Testing Equipment

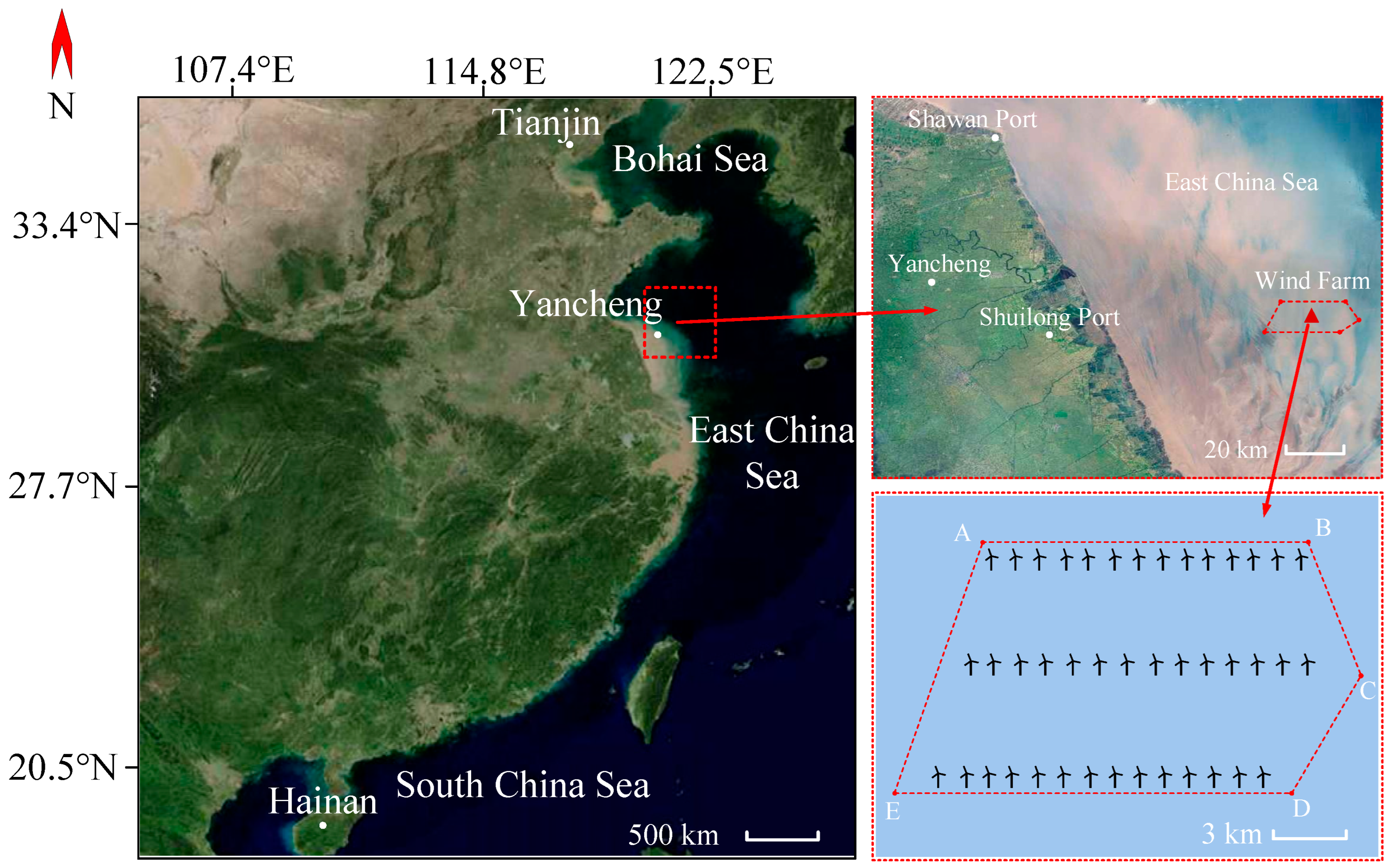

3.2. Experimental Materials

3.3. Specimen Preparation, Saturation, and Consolidation

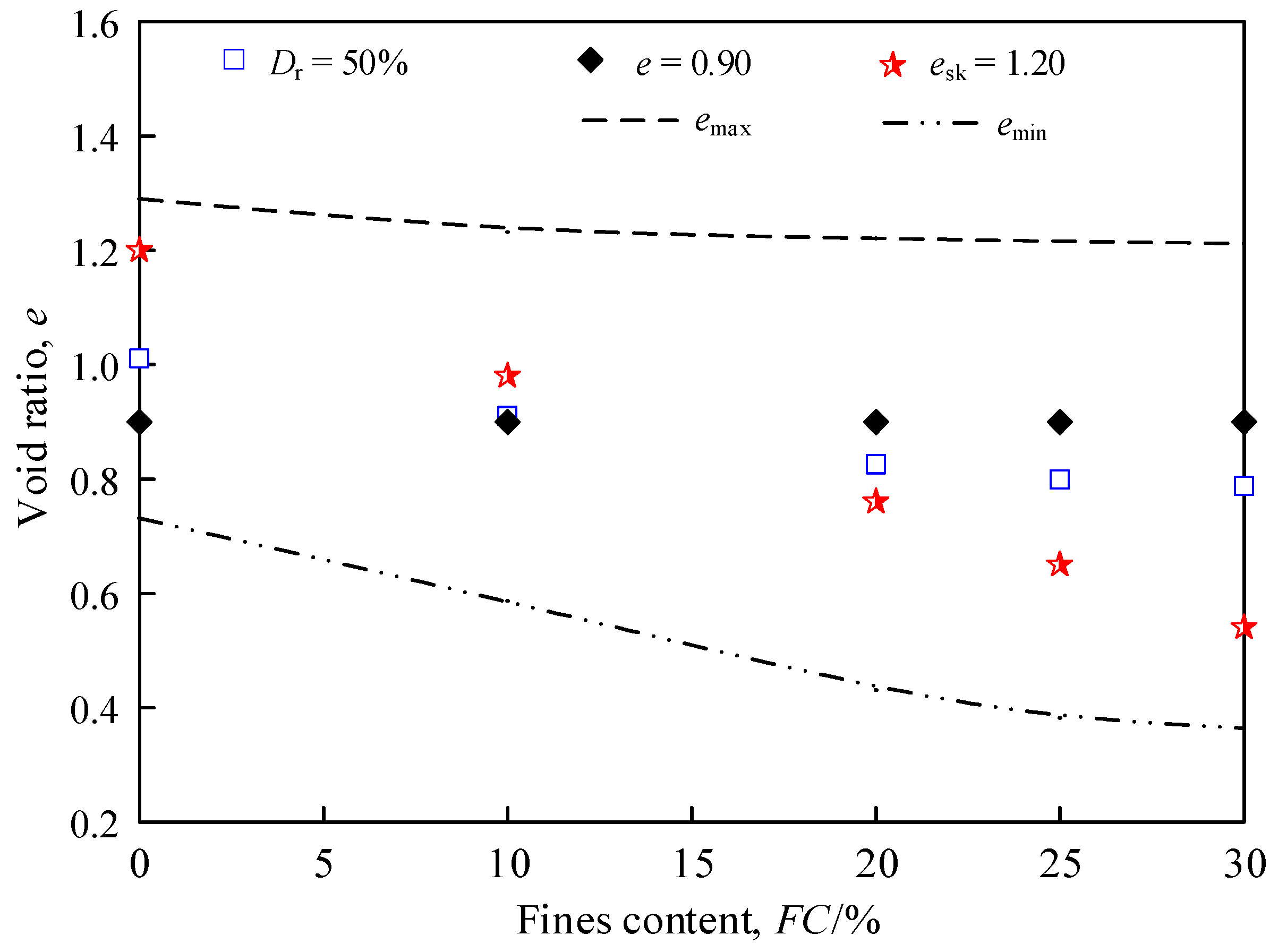

3.4. Experimental Protocol

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

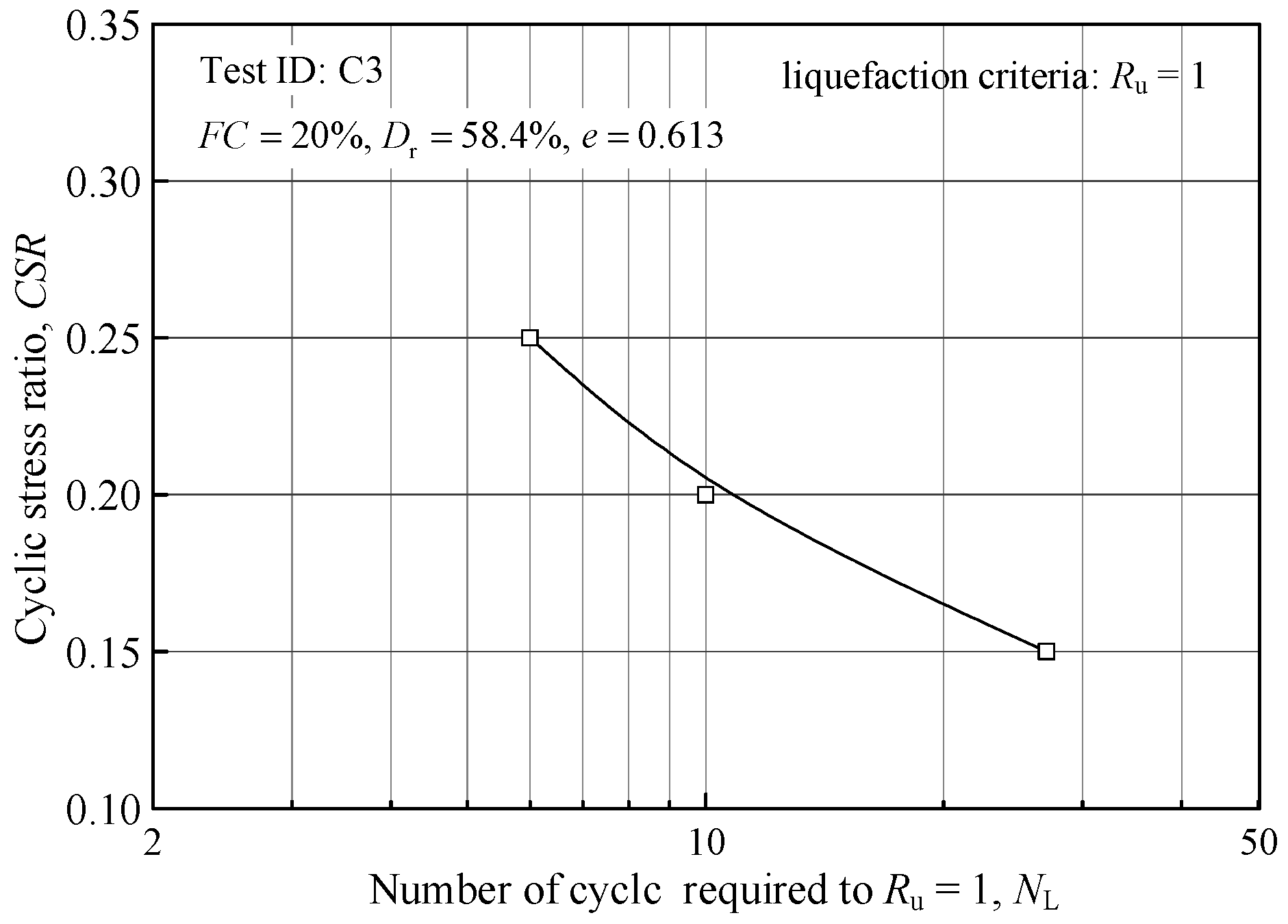

4.1. Liquefaction Criteria for Sandy Soils

4.2. Effect of the Fine Particle Content on the Liquefaction Strength of Sandy Soils

4.3. Relationship Between Liquefaction Strength and Density State Parameters

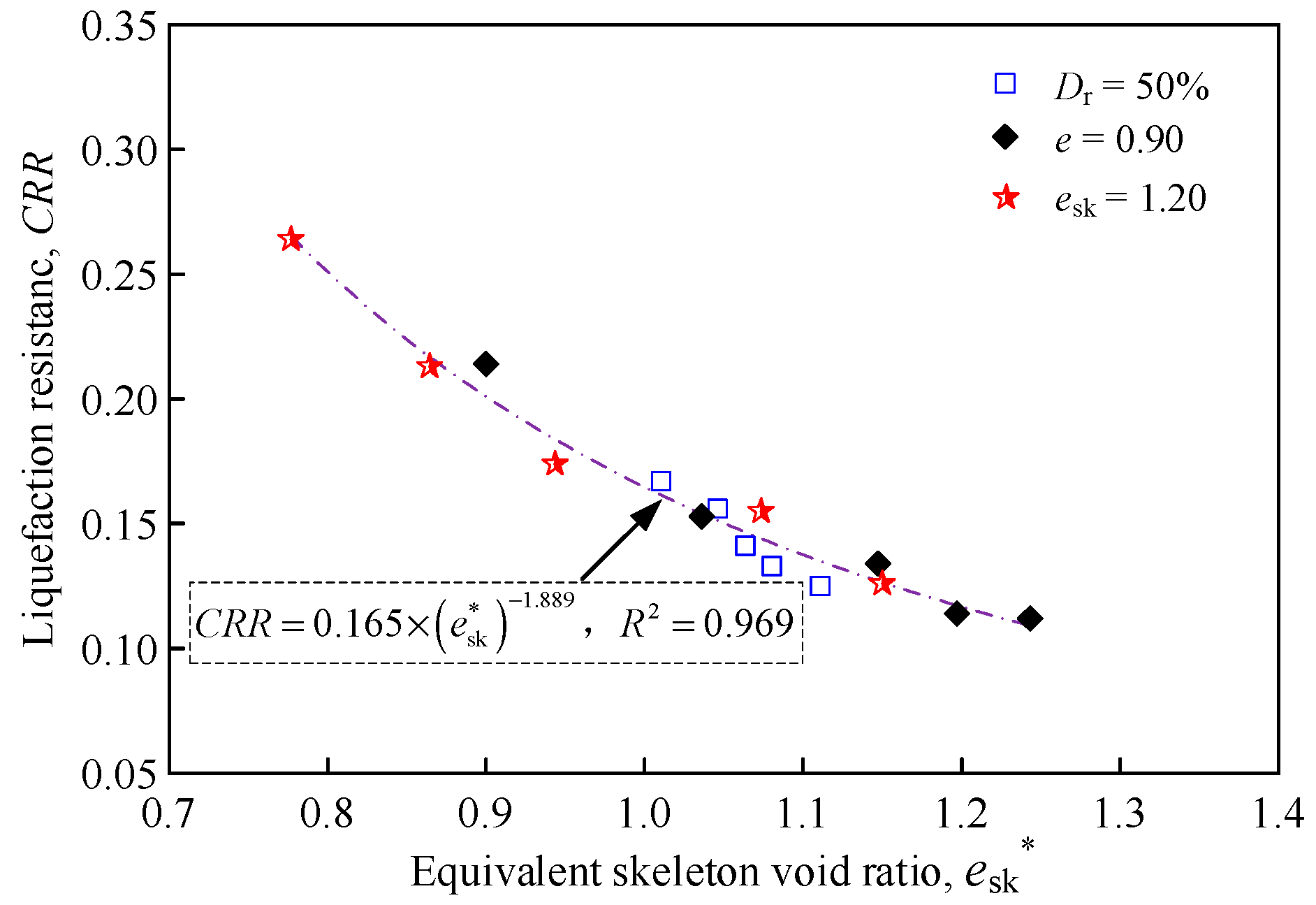

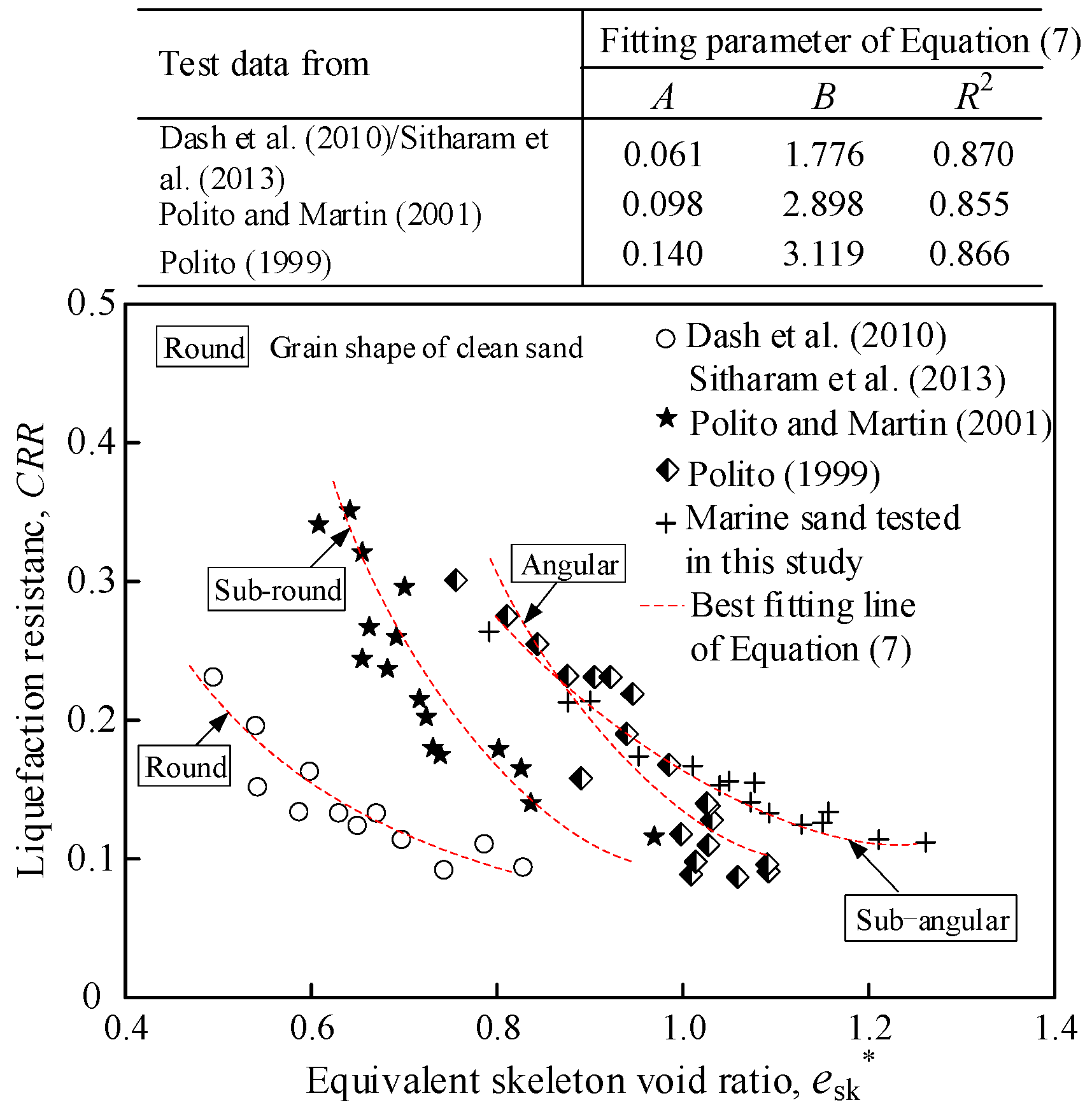

4.4. Characterization of Liquefaction Strength via the Equivalent Skeleton Void Ratio

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, X.-Y.; Li, H.-B.; Rong, W.-D.; Li, W. Joint earthquake and wave action on the monopile wind turbine foundation: An experimental study. Mar. Struct. 2015, 44, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanos, E.I.; Thons, S.; Georgakis, C.T. Wind turbines and seismic hazard: A state-of-the-art review. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 2113–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-X. Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.-X.; Jin, D.-D.; Chang, X.-D.; Li, X.-J.; Zhou, G.-L. Preliminary research on liquefaction characteristics of Wenchuan 8.0 earthquake. Rock Soil Mech. 2013, 34, 2737–2755. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.F.; Alagappan, K.; Gandhi, A.; Donovan, V.; Tewari, M.; Zaets, S.B. Disaster management following the Chi Chi earthquake in Taiwan. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2006, 21, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Juang, C.H.; Wasowski, J.; Huang, R.; Xu, Q.; Scaringi, G.; van Westen, C.J.; Havenith, H.-B. What we have learned from the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake and its aftermath: A decade of research and challenges. Eng. Geol. 2018, 241, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Chen, Y.-M.; Gao, Y.-M. Liquefaction evaluation on sand like gravelly soil deposits based on field vs. measurements during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2024, 343, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, X.-M. Field-observed phenomena of seismic liquefaction and subsidence during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Nat. Hazards 2010, 54, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-M.; Zhang, S.; Huang, R.-Q. Multi-hazard scenarios and consequences in Beichuan, China: The first five years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2014, 180, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasakia, Y.; Towhata, I.; Miyamoto, K.; Shirato, M.; Narita, A.; Sasaki, T.; Sako, S. Reconnaissance report on damage in and around river levees caused by the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Hyodo, M.; Goda, K.; Tazoh, T.; Taylor, C.A. Liquefaction of soil in the Tokyo Bay area from the 2011 Tohoku (Japan) earthquake. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susumu, Y.; Kenji, H.; Keisuke, I.; Yoshiki, K. Characteristics of liquefaction in Tokyo Bay area by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar]

- Towhata, I.; Maruyama, S.; Kasuda, K. Liquefaction in the Kanto region during the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake. Soils Found. 2014, 54, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unjoh, S.; Kaneko, M.; Kataoka, S. Effect of earthquake ground motions on soil liquefaction. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standardization Administration of China. Soil Engineering Classification Standards; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-Z.; Chen, G.-X. Experimental study on influence of clay particle content on liquefaction of Nanjing fine sand. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2003, 23, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.K.; Vrymoed, J.L.; Uyeno, C.K. The effect of fines on liquefaction of sands. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, 10–15 July 1977; Japanese Society of Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering: Tokyo, Japan, 1977; pp. 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Polito, C.P.; Martin, J.R., II. Effects of nonplastic fines on the liquefaction resistance of sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitharam, T.G.; Dash, H.K.; Jakka, R.S. Post-liquefaction undrained shear behavior of sand-silt mixtures at constant void ratio. Int. J. Geomech. 2013, 13, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, D.H.; Phan, V.T.A.; Hsieh, Y.T. Engineering behavior and correlated parameters from obtained results of sand–silt mixtures. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 77, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-Y.; Cai, F.; Zhang, J. Evaluation of grain size and content of nonplastic fines on undrained behavior of sandy soils. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2020, 39, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseller Bayat, E.E.; Monkul, M.M.; Akin, Ö. The coupled influence of relative density, CSR, plasticity and content of fines on cyclic liquefaction resistance of sands. J. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 23, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevanayagam, S. Effect of fines and confining stress on undrained shear strength of silty sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1998, 124, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevanayagam, S.; Martin, G.R. Liquefaction in silty soils—Screening and remediation issue. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2002, 22, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeini, S.A.; Baziar, M.H. Effect of fines content on steady-state strength of mixed and layered samples of sand. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2004, 24, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Lo, S.R.; Gnanendran, C.T. On equivalent granular void ratio and steady state behaviour of loose sand with fines. Can. Geotech. J. 2008, 45, 1439–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mohtar, C.S. Evaluation of the 5% double amplitude strain criterion. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Alexandria, Egypt, 5–9 October 2009; pp. 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Skempton, A.W. The pore-pressure coefficients A and B. Géotechnique 1954, 4, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2216-19; ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Water Content of Soil by Mass. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D5311/D5311M-13; Standard Test Method for Load-Controlled Cyclic Triaxial Strength of Soil. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Japanese Geotechnical Society. Method for Cyclic Triaxial Test on Soils; Japanese Geotechnical Society: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.-R.; Xin, S.-L.; Wang, B.-H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Wu, Q.; Ma, W.-J.; Qin, Y. Experimental analysis on the cyclic strength and deformation characteristics of marine coral sand under different loading frequencies. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 190, 109165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawinkler, H. Cyclic Loading Histories for Seismic Experimentation on Structural Components. Earthq. Spectra 1996, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K. Stability of natural deposits during earthquakes. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–16 August 1985; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 1, pp. 321–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, K. Liquefaction and flow failure during earthquakes. Géotechnique 1993, 43, 351–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, H.B. Soil liquefaction and cyclic mobility evaluation for level ground during earthquakes. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1979, 105, 201–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, C.; Houlsby, G.T.; Byrne, B.W. Response of Stiff Piles in Sand to Long-Term Cyclic Lateral Loading. Géotechnique 2010, 60, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallehave, D.; Byrne, B.W.; Thienen, S.V.; Mikkelsen, K.K. Optimization of Monopile Support Structures for Offshore Wind Turbines. Eng. Struct. 2015, 100, 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.W.; Houlsby, G.T.; Burd, H.J.; Gavin, K.; McAdam, R.; Taborda, D.; Zdravković, L. PISA Design Model for Monopile Foundations in Sand. Géotechnique 2019, 69, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, H.B.; Martin, P.P.; Lysmer, J. The Generation and Dissipation of Pore Water Pressures During Soil Liquefaction; College of Engineering, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- De Alba, P.; Seed, H.B.; Chan, C.K. Sand liquefaction in large-scale simple shear tests. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1976, 102, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokimatsu, K.; Yoshimi, Y. Empirical correlation of soil liquefaction based on SPT N-value and fines content. Soils Found. 1983, 23, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-H.; Chen, G.-X.; Sun, T. Liquefaction resistance of sand-gravel soils using small soil-box shaking table tests. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.J.; Hong, M.L. Effects of clay content on liquefaction characteristics of gap-graded clayey sands. Soils Found. 2008, 48, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, G.-X.; Zhou, Z.-L. Influence of fines content on cyclic resistance of fines-s0nd-gravel mixtures. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 39, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Tika, T. The effect of fines on critical state and liquefaction resistance characteristics of non-plastic silty sands. Soils Found. 2008, 48, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevanayagam, S.; Shenthan, T.; Mohan, S. Undrained fragility of clean sands, silty sands, and sandy silts. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2002, 128, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Lo, S.R.; Baki, M.A.L. Equivalent granular state parameter and undrained behaviour of sand–fines mixtures. Acta Geotechnica 2011, 6, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Qadimi, A. A simple critical state approach to predicting the cyclic and monotonic response of sands with different fines contents using the equivalent intergranular void ratio. Acta Geotechnica 2015, 10, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, H.K.; Sitharam, T.G.; Baudet, B.A. Influence of non-plastic fines on the response of a silty sand to cyclic loading. Soils Found. 2010, 50, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, C.P. The Effects of Non-Plastic And Plastic Fines on the Liquefaction of Sandy Soils. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Test ID | FC (%) | Dr (%) | e | esk | b | esk* | Test ID | FC (%) | Dr (%) | e | esk | b | esk* | Test ID | FC (%) | Dr (%) | e | esk | b | esk* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0 | 50.0 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0 | 1.01 | B1 | 0 | 69.8 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0 | 0.90 | C1 | 0 | 16.001 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0 | 1.16 |

| A2 | 10 | 50.0 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 0.36 | 1.04 | B2 | 10 | 51.5 | 0.90 | 1.11 | 0.36 | 1.03 | C2 | 10 | 39.1 | 0.94 | 1.15 | 0.21 | 1.10 |

| A3 | 20 | 50.0 | 0.83 | 1.28 | 0.43 | 1.06 | B3 | 20 | 40.7 | 0.90 | 1.38 | 0.44 | 1.14 | C3 | 20 | 58.4 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 0.43 | 0.94 |

| A4 | 25 | 50.0 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 0.47 | 1.07 | B4 | 25 | 37.9 | 0.90 | 1.53 | 0.47 | 1.19 | C4 | 25 | 67.9 | 0.61 | 1.15 | 0.47 | 0.86 |

| A5 | 30 | 50.0 | 0.79 | 1.55 | 0.53 | 1.08 | B5 | 30 | 36.8 | 0.90 | 1.71 | 0.49 | 1.24 | C5 | 30 | 79.2 | 0.51 | 1.15 | 0.50 | 0.77 |

| Data Source | Test Material | Grain Shape | Basic Physical Properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand + Fine | Sand + Fine | emax-s/emax-f | emin-s/emin-f | d50-s/d50-f (mm) | d10-s/d10-f (mm) | Cu-s/Cu-f | |

| Dash et al. [50] Sitharam [19] | Ahmedabad sand + Bangalore quarry dust | Round + Round | 0.68/1.63 | 0.42/0.52 | 0.375/0.037 | 0.121/N.D. | 3.58/7.83 |

| Polito and Martin [18] | Monterey No. 0/30 sand + Yatesville silt | Sub-round + Sub-angular | 0.82/1.72 | 0.63/0.74 | 0.430/0.032 | 0.310/0.009 | 1.55/4.39 |

| Polito [51] | Yatesville sand + Yatesville silt | Angular + Sub-angular | 0.97/1.72 | 0.65/0.74 | 0.180/0.032 | 0.089/0.009 | 2.45/4.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Q.; Wu, S. Effect of Fine Content on Liquefaction Resistance of Saturated Marine Sandy Soils Subjected to Cyclic Loading. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122333

Gao S, Zhang W, Wu Q, Wu S. Effect of Fine Content on Liquefaction Resistance of Saturated Marine Sandy Soils Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122333

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Shang, Wenwen Zhang, Qi Wu, and Shuanglan Wu. 2025. "Effect of Fine Content on Liquefaction Resistance of Saturated Marine Sandy Soils Subjected to Cyclic Loading" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122333

APA StyleGao, S., Zhang, W., Wu, Q., & Wu, S. (2025). Effect of Fine Content on Liquefaction Resistance of Saturated Marine Sandy Soils Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122333