1. Introduction

Structural collapse is defined as an ultimate limit state in which the structure can no longer sustain applied loads including tension, compression, bending, shear, or torsion. When longitudinally oriented elements in a structure lose their integrity, global longitudinal structural collapse occurs, followed by significant loss of bending, shear, and torsion stiffness. In contrast, global transverse collapse is initiated by the failure of transverse frames, which also causes longitudinal structures to lose support. These two collapse modes are not entirely independent; longitudinal failure can trigger the collapse of one or more transverse frames, thereby affecting extended segments of the structure [

1]. Bending load has the most impact on the longitudinal structural collapse of the ship’s hull; therefore, longitudinal hull girder capacity is defined as the maximum bending moment sustainable on the transverse cross-section of the critical longitudinal structural segment.

If the maximum bending load capacity is reached, it is considered that the global longitudinal collapse will occur; i.e., progressive loss of structural components of critical segment leads to decreasing flexural stiffness on a critical level. Progressive collapse of structural members occurs due to yielding (compressive or tensile loading) and/or buckling (local and global) of longitudinal elements under compressive loading.

Nowadays, hull girder ultimate strength, as an integral part of Classification Society Rules, is assessed in the design phase, and it can have a considerable effect on dimensioning strength deck structural members of single-deck ships like tankers or bulk carriers [

2]. It is usually expressed as the maximum vertical bending moment the ship’s hull can absorb, i.e., the ultimate bending moment.

Considerable research in this field, with a description of calculation methods, is presented in the ISSC reports [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Contemporary methods generally used for the determination of ultimate bending moment are as follows:

Incremental–iterative progressive collapse analysis method: This analytical method, prescribed by the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) Common Structural Rules (CSR), is based on the Smith approach [

7], which is also commonly called Smith’s method. A very efficient and fast method based on a two-dimensional cross-section with sufficient accuracy, it is easy to incorporate into existing ship design software compliant with the Rules [

2]. Last year, the Smith-based approach was further extended by several research groups. Tanaka et al. [

8] includes the influence of shear stresses, while Fujikubo and Tatsumi [

9] extend the method with the influence of bottom lateral pressure.

Nonlinear finite element method (NLFEM) [

10,

11]: The most accurate and complex method includes the discretization of a structural model (choosing the appropriate finite element size) and the implementation of geometrical and material nonlinearity in computation. Depending on the size of the structural FEM model, the calculation time varies from a few hours to a few days, and it also requires significant knowledge and experience in defining structural models correctly and setting all the calculation parameters. The structural FEM model ranges from a very basic stiffened panel model to a partial multi-hold model or a very complex full-ship model [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Since it is not possible to perform a fracture test of a ship’s structure due to its dimensions, tests are performed on small-scale models representing simplified sections of the ship (a typical hull configuration) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], although the differences in scale can cause a problem in comparisons of the results and validation for full-scale models. Results of the NLFEM calculation given in this study were compared with the experimental results [

27] for the collapse of a box girder model of the same size and with numerical results from other researchers [

3].

The objectives of this research are as follows:

Comparison of different numerical tools for NLFEM analysis. The box girder example has been analyzed using FEMAP/NX Nastran, version 2406.27 (implicit analysis is adopted) and LS-Dyna software, version smp d R11.1.0 (explicit analysis is adopted).

Comparison of the results obtained by the previously mentioned numerical NLFEM tools with results from other researchers [

3] and with the result of our physical experiment [

27].

Comparison of Smith-based method with NLFEMs and experimental results.

Although the NLFEM type of analysis is used more and more in structural calculations, the discrepancy in results on relatively simple models can be high. The purpose of this study is to investigate the level of uncertainty in an ultimate strength calculation using NLFEM on box girder examples.

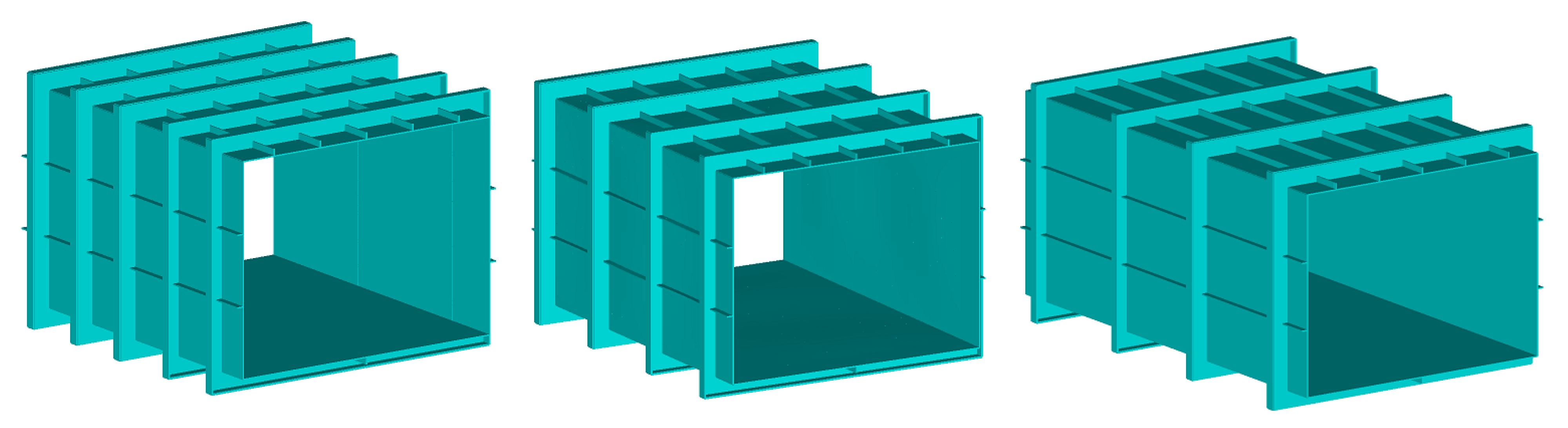

2. Physical Experiment

The physical experiment was conducted on three box girder models, designated H200, H300, and H400, where the number denotes the transverse frame spacing; see

Figure 1. All models were fabricated from high-tensile steel HTS690. Detailed specifications of the models, along with the experimental results, are provided in [

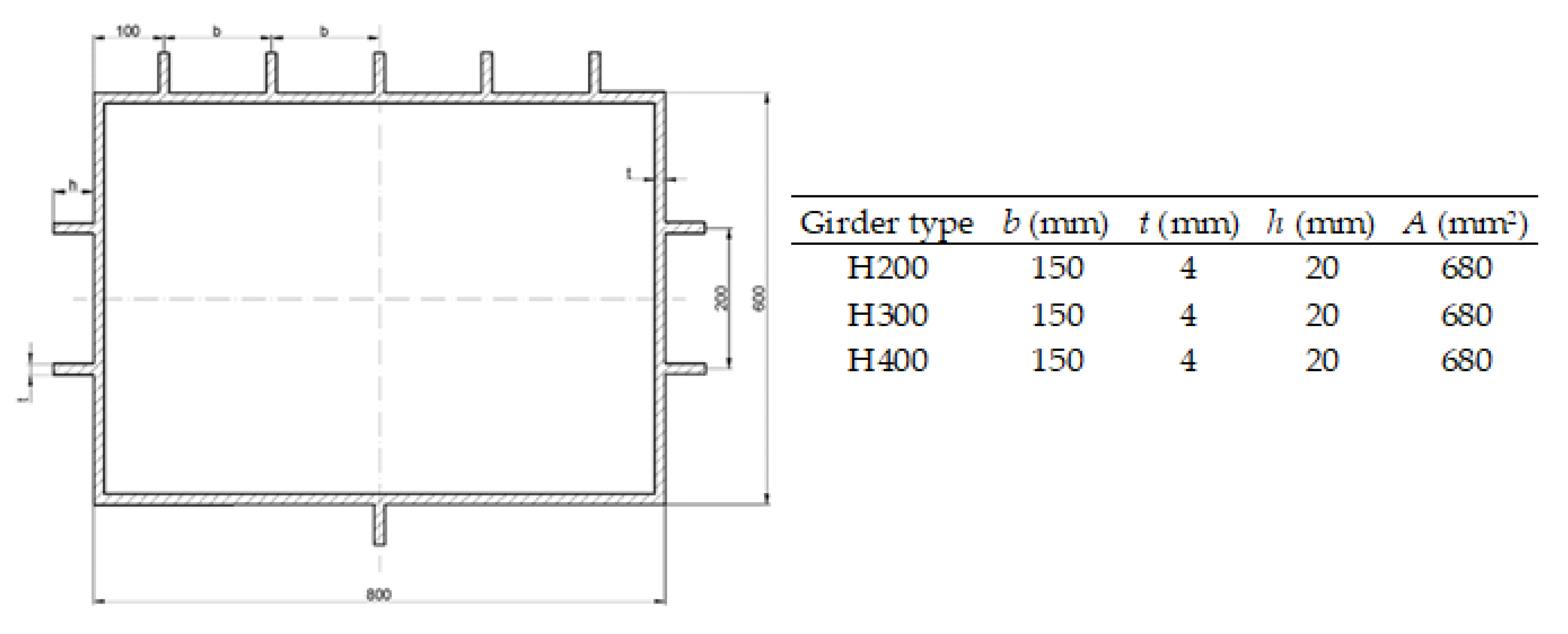

27]. The cross-sectional geometry of the box girders is shown in

Figure 2 with corresponding dimensions. All girders share an identical cross-section, featuring longitudinal stiffeners of type FB 20×4 mm, and plate thicknesses of 4 mm.

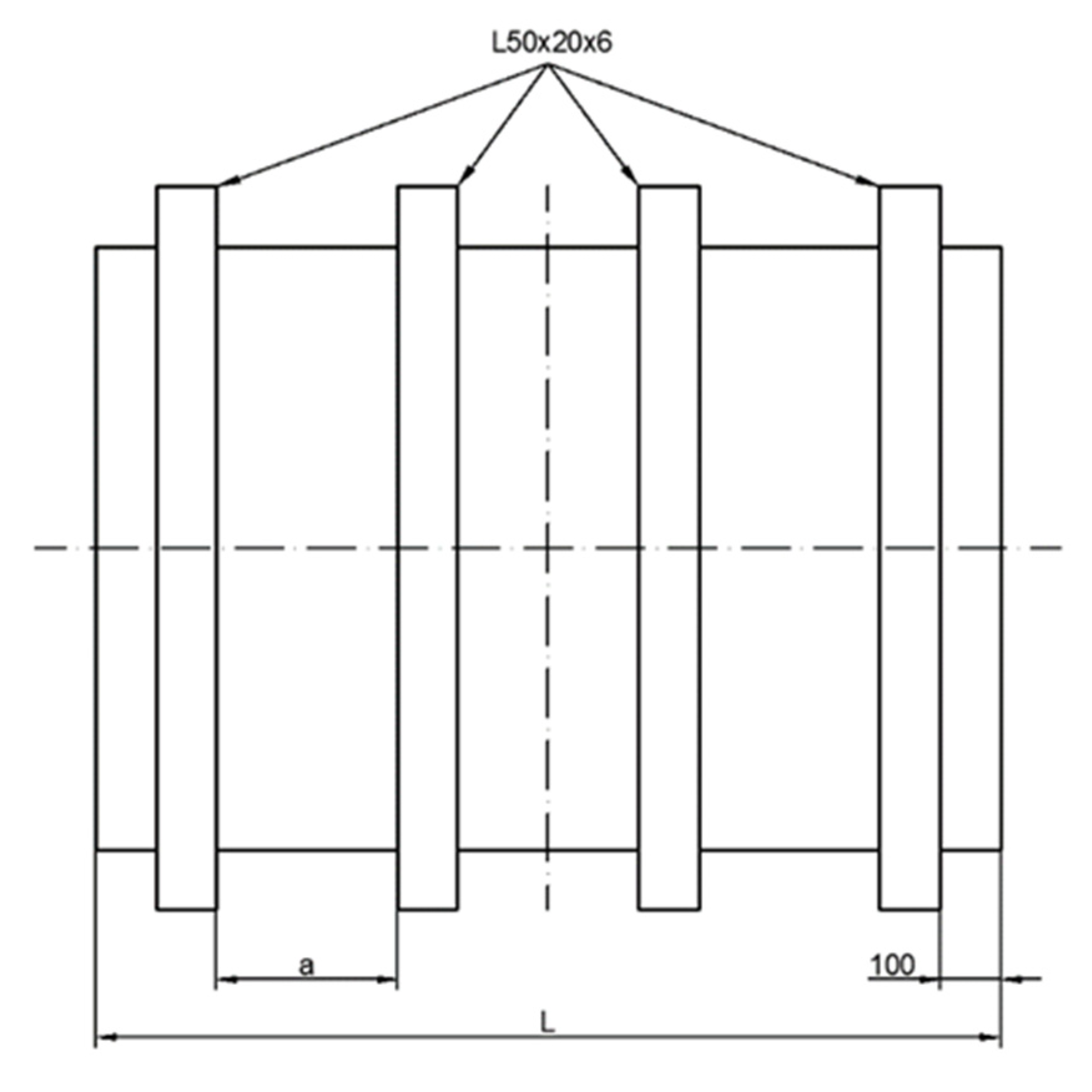

Transverse frames are “L”-shaped and made of mild steel with a different span for each model. The side view of a box girder is shown in

Figure 3, and dimensions are given in

Table 1.

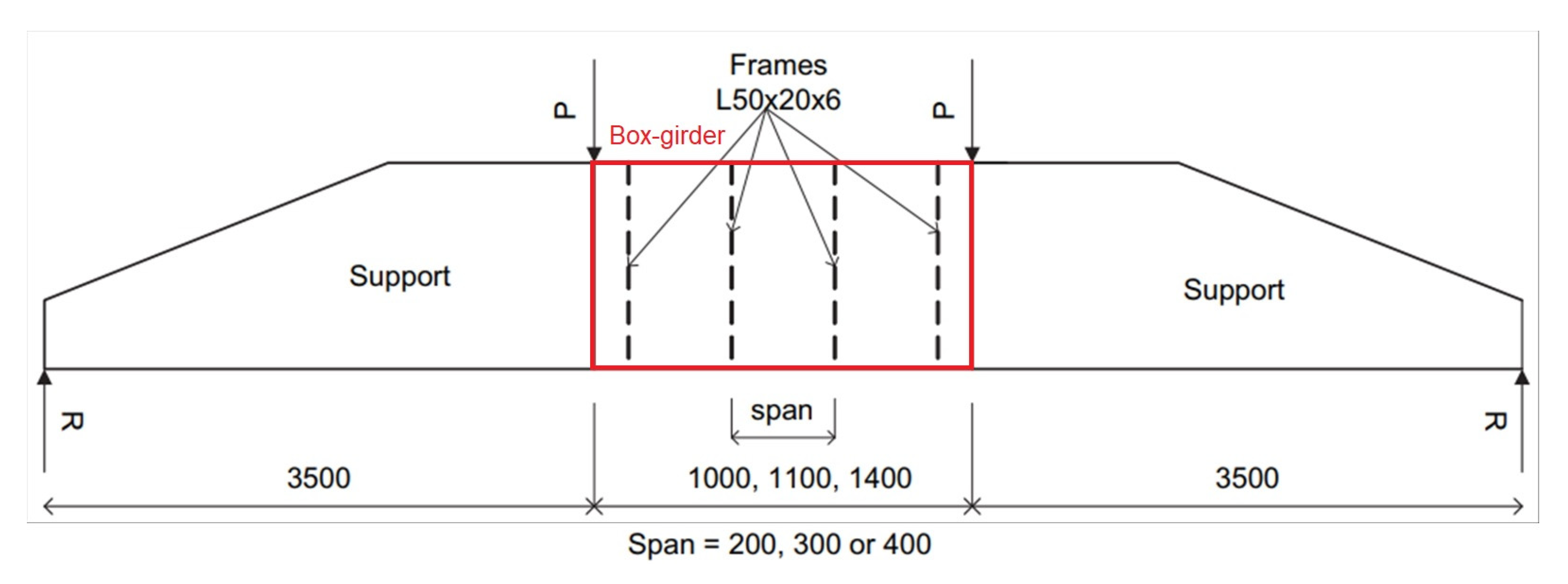

The experiment is conducted as a four-point bending of the box girder as a beam. The beam is divided into three parts: the evaluated box girder is positioned in the middle, with two supporting structures on both ends, as shown in

Figure 4. This model is then subjected to pure bending moment, inducing compression on the top plate and tension on the bottom plate of the box girder.

3. FEA Model, Loads, and Boundary Conditions

In this chapter, the preparation of a finite element model for calculating the longitudinal ultimate strength is explained. The software used for calculation was FEMAP/NX Nastran and LS-Dyna. For a more realistic response (concerning large displacement, deformation, and material yielding), the geometrical and material nonlinearities are considered within the nonlinear finite element method employed. The Newton–Raphson method was used for incremental–iterative solving of equilibrium convergence [

10]. The boundary conditions are also described together with the applied load and imposed initial geometrical imperfection, which contributes to the more realistic initial state of the box girder.

3.1. FE Model Parameters

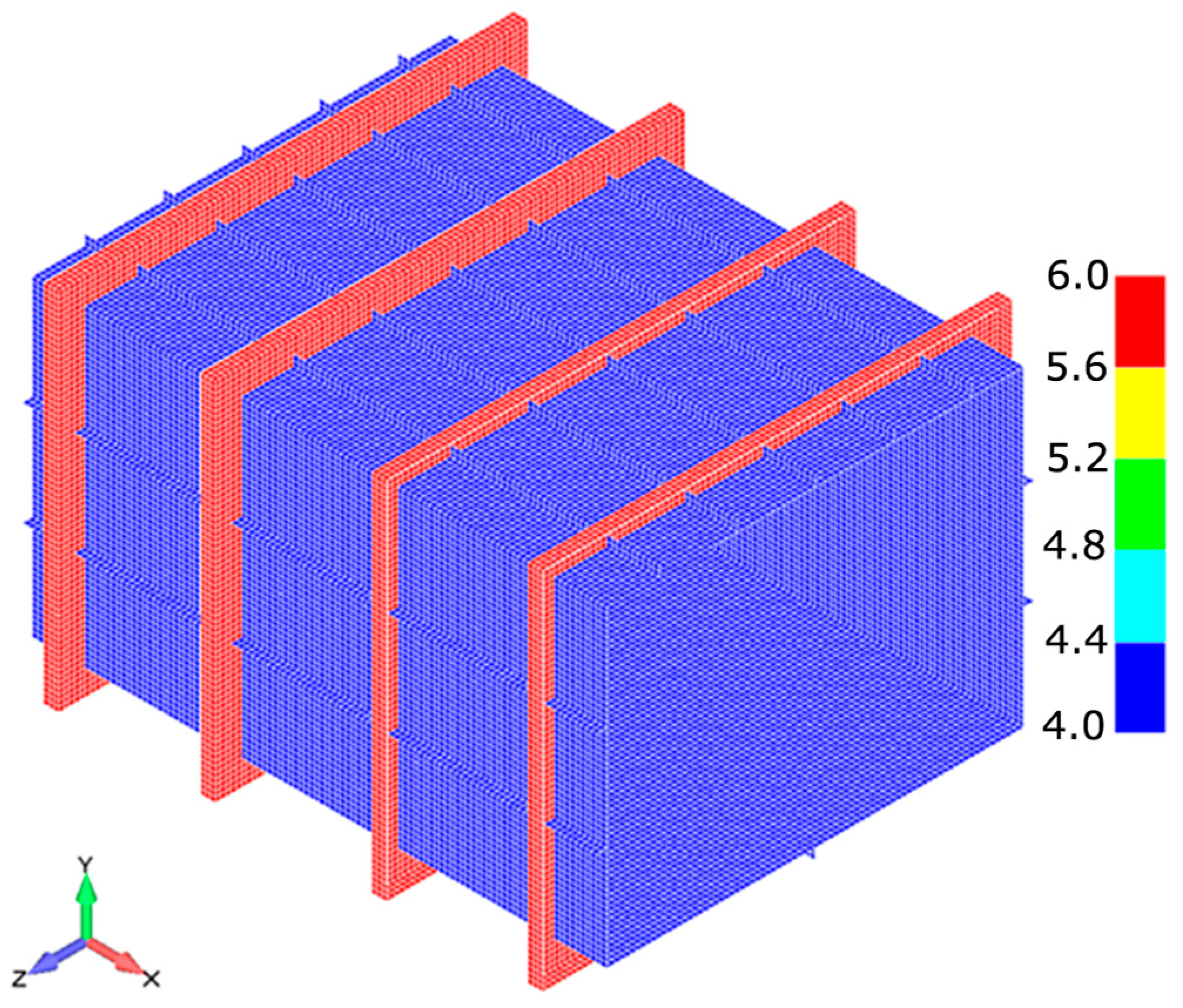

Three FEM box girder models (H200, H300, and H400) are modeled with and without imposed initial geometric imperfection. Four-node shell elements were used for discretization. All finite elements in all models are the same size, measuring 10 mm × 10 mm.

Figure 5 represents the discretized H300 model, displaying the thickness of the plate, stiffeners, and transverse frames. Following data given in [

3], material nonlinearity is considered and idealized as elastoplastic (bi-linear), where HTS690 has a nominal yield strength defined as 732 MPa and mild steel 235 MPa with E = 210 GPa.

3.2. Boundary Conditions and Model Loading

All three models have the same boundary conditions imposed. Structural models are constrained on both ends with rigid elements. A rigid element connects all nodes (slave) on the edge of the box girder with one node (master) in the centroid of the cross-section of that edge. On the left side of the structural model, the master node is constrained in all degrees of freedom except for translation in the longitudinal direction (x-axis). Through the rigid connection, all slave nodes inherit the constraints of the master node. On the right end, the master node was fully constrained in all six degrees of freedom (three translations and three rotations).

The load was applied to the master nodes as an enforced rotation about the y-axis, with a total rotation of 0.0075 radians. To simulate pure vertical bending, the load was introduced incrementally, which allowed the influence of other components—such as horizontal bending, torsional moments, shear forces, and localized pressures—to be effectively neglected.

3.3. Initial Geometric Imperfections

Since a ship hull is a thin-walled welded structure, the presence of initial structural imperfections, i.e., residual stress and initial geometric imperfections (IGIs), is inevitable [

28,

29]. While the direct consideration of residual stresses in numerical models is often avoided due to the complexity of their accurate representation, initial geometric imperfections are typically included, as their shape and amplitude can have a significant influence on bending plates in compression and are much simpler to incorporate into computation. Methods based on the Smith approach consider the effect of initial geometric distortions implicitly within the formulation of load–end shortening curves [

30,

31], while NLFEA requires repositioning the nodes of the ideal meshed model with the recommended calculation method.

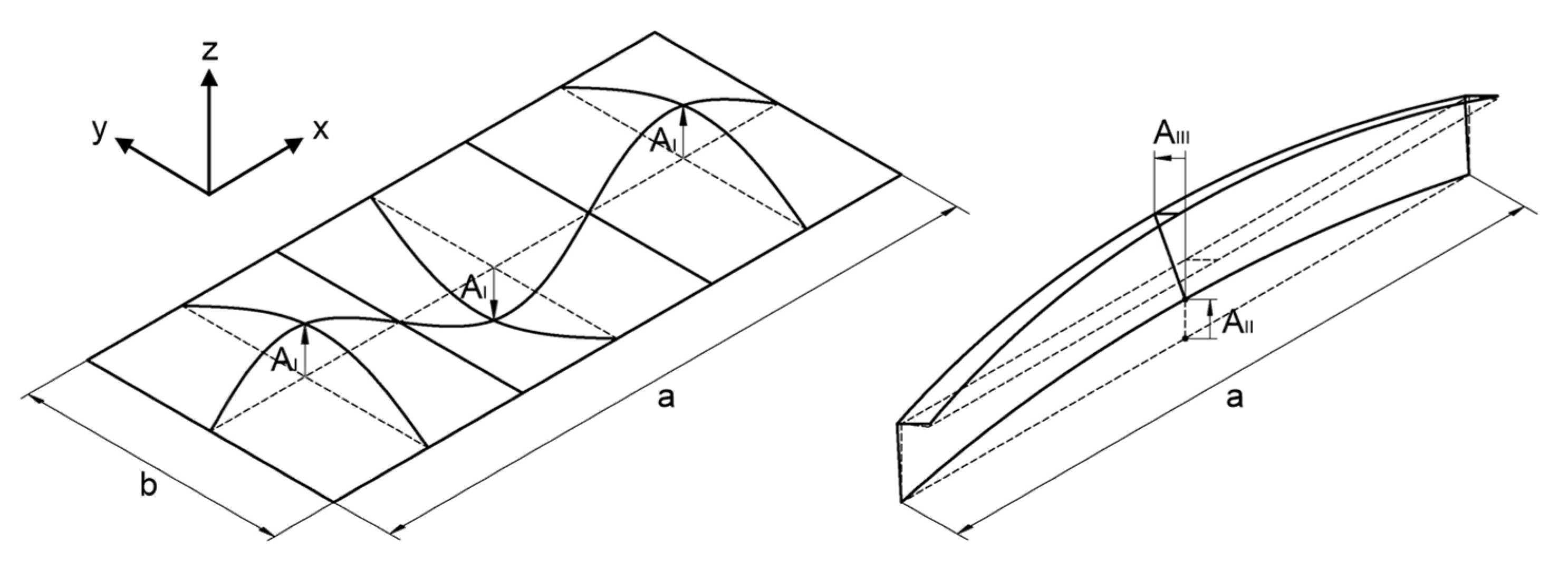

Initial geometric imperfections (IGIs) in stiffened panels consist of the following [

1]:

Initial plate deflection between stiffeners vertically to plate plane (type I)the first type of plate buckling between stiffeners;

Initial deflection of stiffeners and plate in-between vertically to plate plane (type II)—the first type of global beam-column buckling with attached breadth of plating;

Initial deflection of stiffeners in the lateral direction (type III)—local web buckling.

All three types of initial geometric imperfections are shown in

Figure 6. Periodic functions defined as Fourier series are used for the idealization of all three types of IGIs. The final shape of imposed IGIs is obtained by their superposition. Vertical displacement (z-direction) for the i-position of the observed stiffened panel is given by

In Equation (1), m is the minimum integer number of buckling mode half-waves in the x-direction, while n is the minimum integer number of buckling mode half-waves in the y-direction. Every type of initial geometric imperfection has its own imperfection amplitude. The amplitude for imperfection type I can described in two ways, as follows:

In Equation (4),

CIa is a dimensionless parameter for the average level of initial deflection for the steel plate which, according to the classification society rules, is 0.005 [

1], while in formulation in Equation (5), β is the slenderness ratio

. The amplitude of the initial deflection in Equation (5) is appropriate for various plate thicknesses (

tp) with the parameter

CIb depending on the amount of initial deflection as follows:

The amplitude of imperfection, denoted as

AII for type II, is set at 0.0015 m for the average level of initial geometric imperfections, according to classification society rules [

1].

Figure 5 illustrates the horizontal deflection (in the y-direction) at the

i-position of the stiffener for the observed stiffened panel:

Unfortunately, no data about measured imperfections was available in [

27]; it was just reported that the panel was relatively flat with a minimal level of imperfection. Therefore, all imperfection parameters used in this study are nominal and based on average statistical levels appropriate to ship type plating. The imperfection amplitudes used in all three models (H200, H300, and H400) are

AI = 0.4 mm;

AII = 1.5 mm; and

AIII = 1.5 mm, as given in [

3], to facilitate comparison with the results of other researchers.

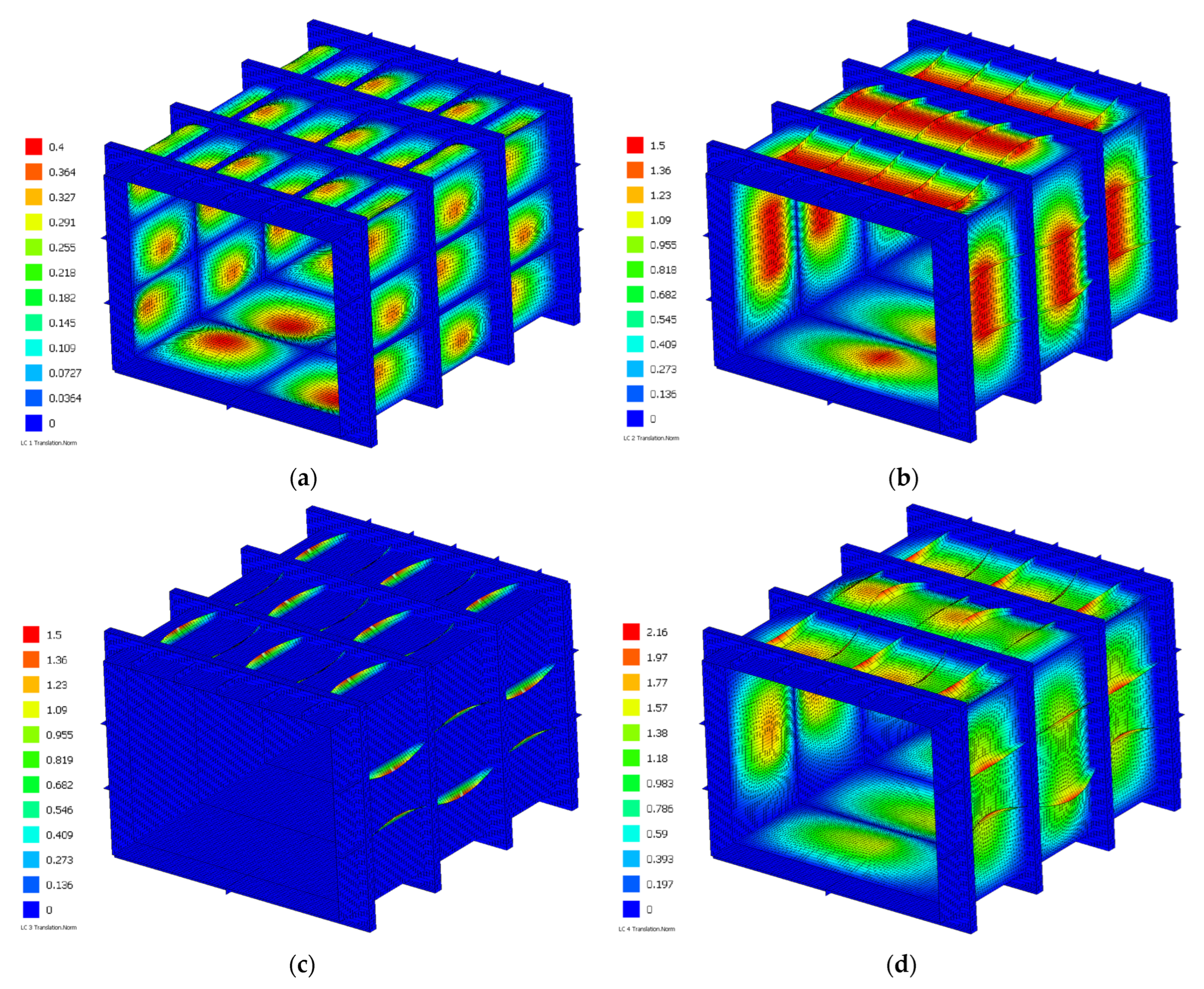

Figure 7 shows the H300 finite element model with incorporated initial geometric imperfections. Type I IGOs are magnified one hundred times, and the others (Type II and III) are magnified twenty times for better viewing. As can be seen in

Figure 7, type II IGIs alternate in the longitudinal direction with bulging of the stiffeners and plate in the middle of the span as suggested in [

3]. Type I and type III IGIs alternate in both directions as shown in

Figure 7. IGIs are implemented into FEM models with the in-house program modules developed at the University of Zagreb (UNIZG).

4. Results

4.1. Collapse Sequence Analysis

For all three models, the collapse sequence is analyzed in detail.

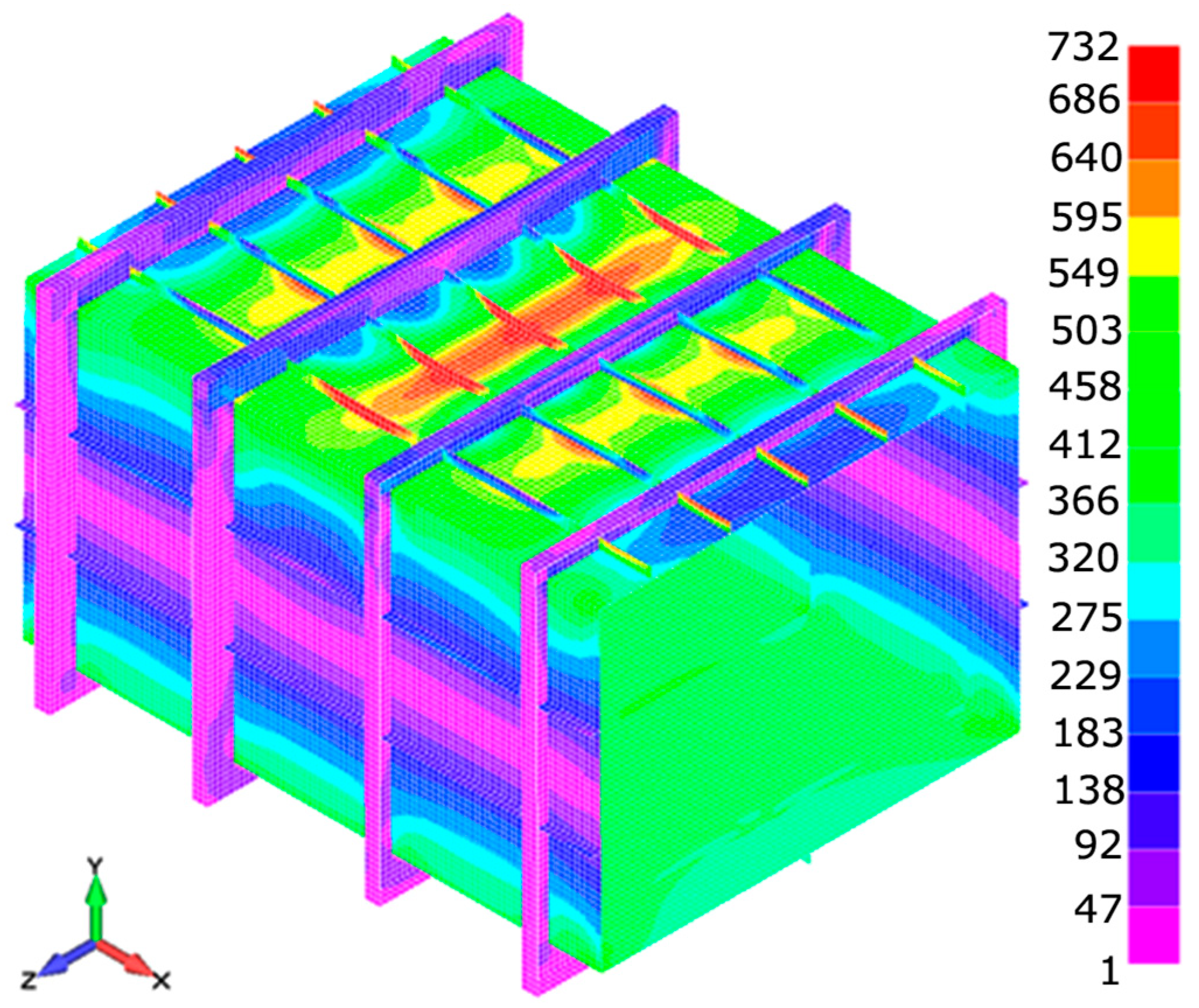

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show von Mises equivalent stress for model H300 in three phases, the subcritical, limit state (maximum bending moment achieved), and post-collapse phase, for the calculation results obtained with LS-Dyna. The maximum von Mises stress achieved is 732 MPa.

The collapse analysis of H300 is explained in more detail. As illustrated in

Figure 8, deck stiffeners are the first to experience a high stress level. Collapse is initiated by column buckling failure in stiffeners, after which yielding occurs with continued load increase that leads to the formation of plastic hinges in all deck stiffeners (meaning that stiffeners reach yield stress level); see

Figure 8. Once plastic deformation initiates in the stiffeners, the central deck plating starts to take on a share of the load, leading to elevated stress concentrations in the deck plate and in the upper regions of the side shell plating (shear strake); see

Figure 9. Stiffeners collapse first, then plating takes on the load and is therefore next to collapse. The limit state corresponding to the ultimate bending moment is reached at approximately 70% of the maximum implemented load at curvature around 0.0085 m

−1.

In other models (H200 and H400), the collapse sequence is quite similar.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show the von Mises equivalent stress for model H200 and H400 in limit state (maximum bending moment) for calculation results obtained with LS-Dyna.

Model H200 has the shortest span between frames, and, because of its rigidity, its ultimate bending moment is the highest. On the contrary, model H400 with slender frames reaches the lowest ultimate bending moment with a minimal curvature radius.

The experimental model H300, in the post-collapse phase, as shown in

Figure 10 and referenced in [

27], shows that the largest deflections and deformations occurred in stiffeners, deck plating, and side shell plating in the central part of the model. The numerically obtained deformed shape closely resembles the experimental one, with identical structural components exhibiting yielding; see [

27] for reference. The shape of the resulting deformed model obtained by the numerical method is very much like the experimental one, with identical structural components exhibiting yielding.

4.2. Result Comparison

The results for the calculated ultimate bending moment (

Mult), obtained by various researchers [

3] as well as through experimental work [

27], are presented in

Table 2. Nine researchers, (1) to (9), used shell finite elements for NLFEM, one researcher used solid elements in NLFEM (10), and one used a Smith-based method (11). The researchers are identified by the software tools they used for their respective analyses.

Table 2 also includes the results obtained from this study using the NLFEM implemented in two different software packages: FEMAP/NX Nastran (using an implicit solver) and LS-Dyna (using an explicit solver), as well as the results from a method based on the Smith approach, developed at the UNIZG [

32,

33,

34]. All results refer to the same box girder models (H200, H300, and H400), with an identical imperfection amplitude applied, as described in

Section 3.3.

Based on the data presented in

Table 2, it can be concluded that the ultimate bending moment values (

Mult) obtained through numerical methods by various researchers, as well as the values obtained by UNIZG through this study, differ significantly from the experimental results [

27]. The analysis provided in [

3] highlighted issues with verifying the experimentally measured ultimate bending moment (

Mult). Besides possible differences in modeling parameters (the material model and level of initial geometric imperfections) and the parameters in the physical experiment, further differences in the boundary conditions and load application could provide an explanation.

However, a strong agreement can be observed between the results determined by NLFEM, regardless of the software package or solver type used, and the results achieved in this study.

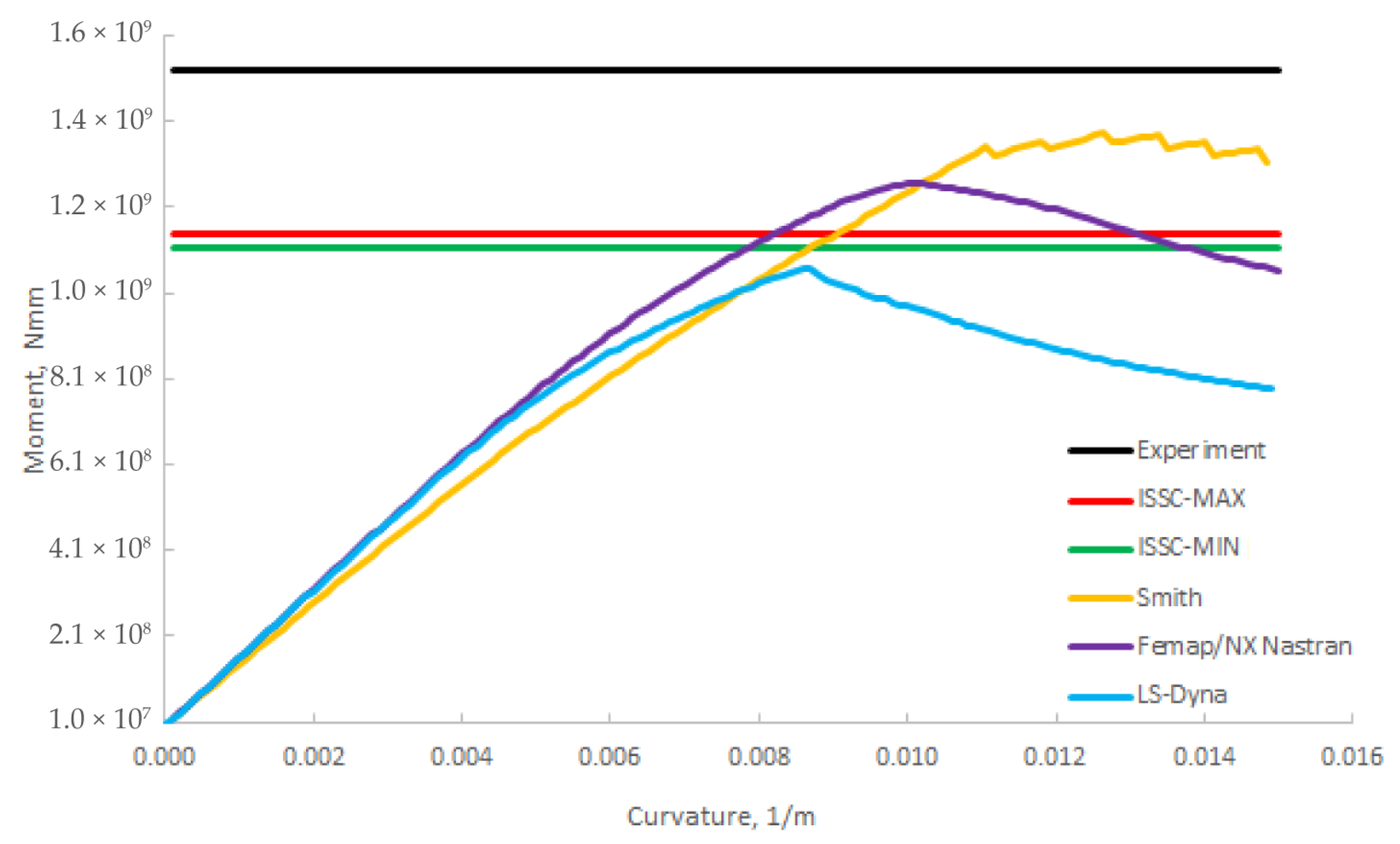

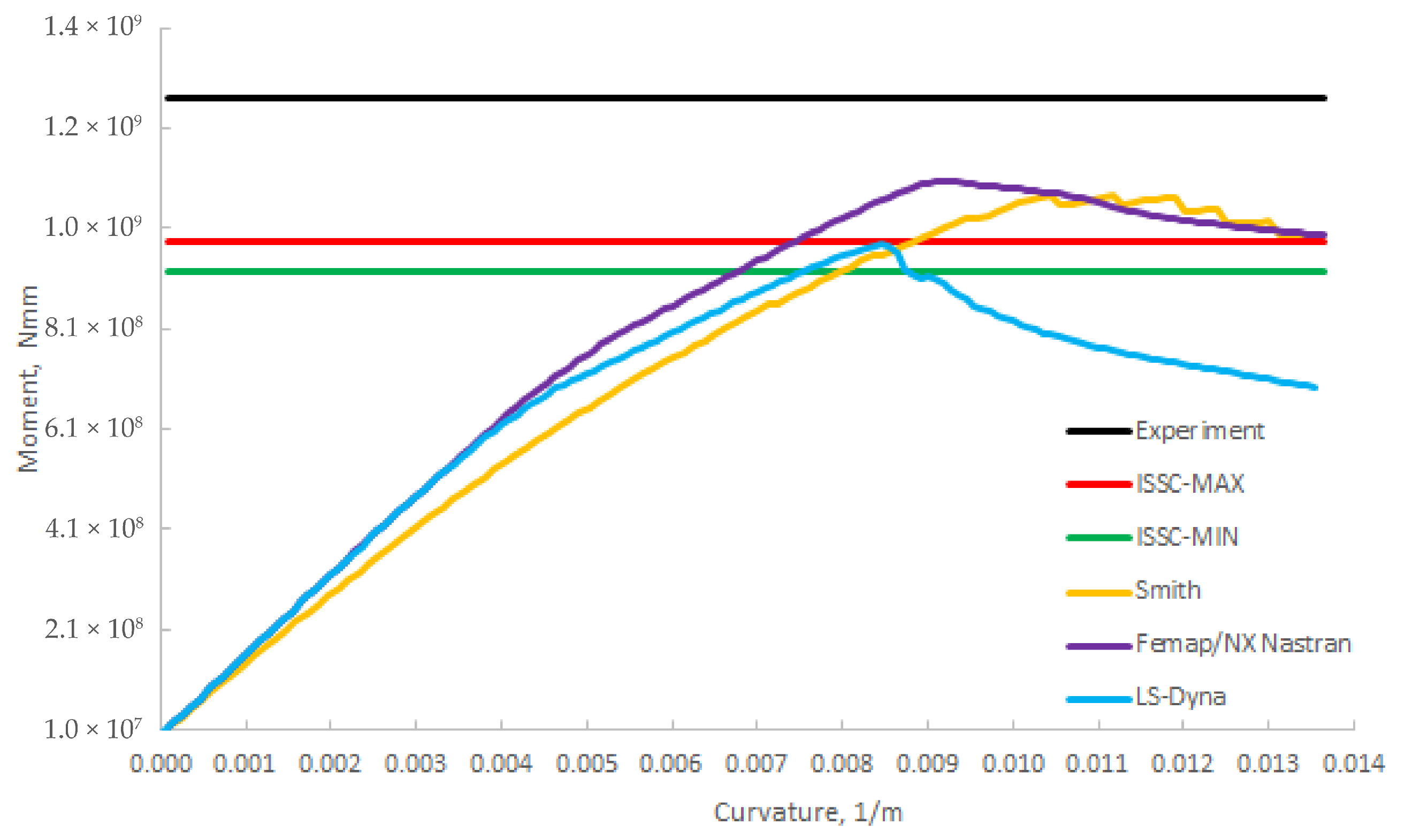

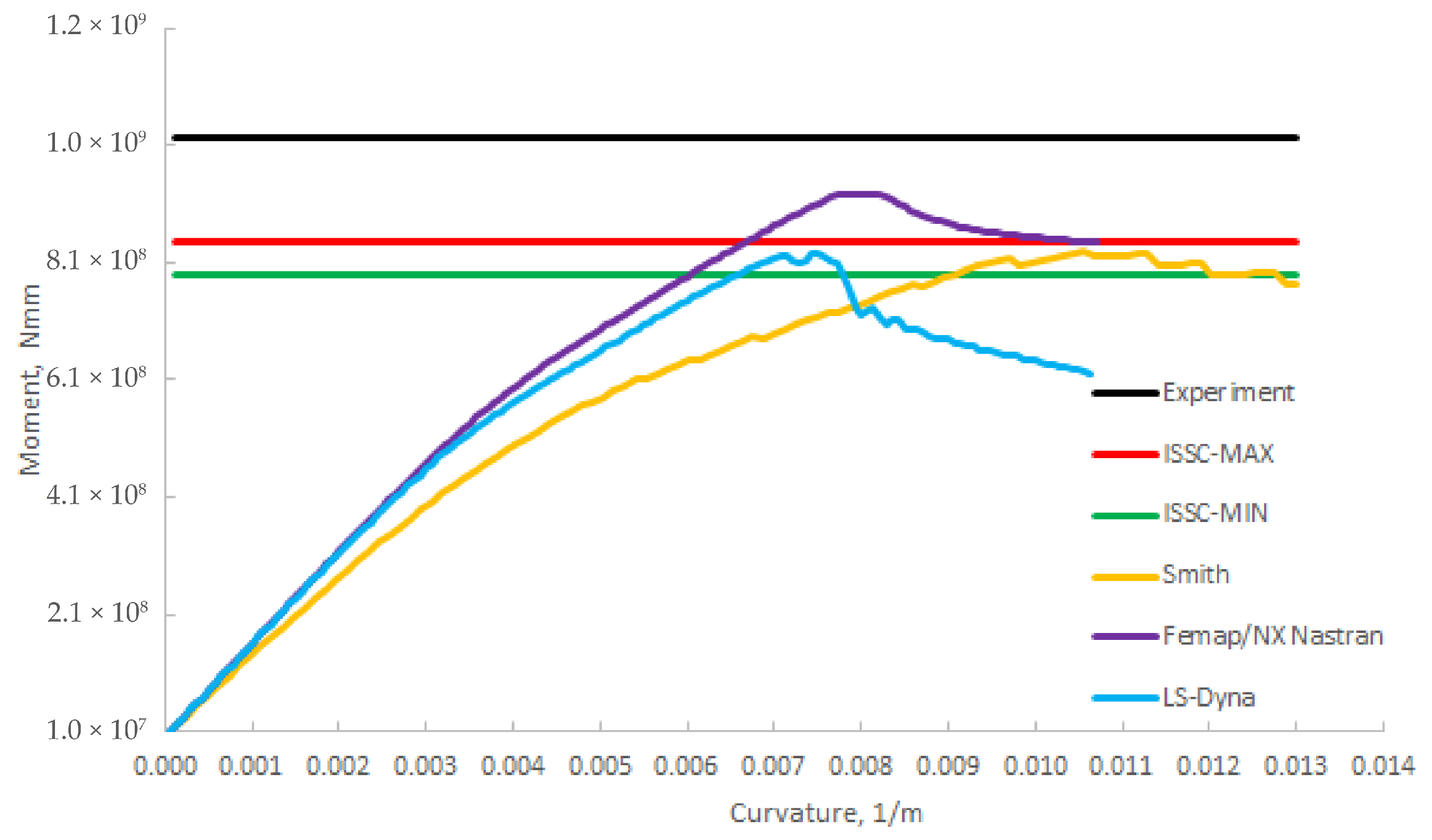

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 illustrate the relation between the vertical bending moment and curvature curves for all three box girders. Results from other researchers are compressed/summarized and presented as ISSC-MIN and ISSC-MAX. The ultimate bending moment occurs at curvature between 0.0088 m

−1 (for H200), 0.0083 m

−1 (for H300) and 0.0077 m

−1 (for H400) for LS-Dyna calculations performed in this study. The moment-curvature line is almost linear up to the curvature between 0.004 m

−1 to 0.005 m

−1; after that point, the deck stiffeners start to buckle, and the slope of the curve changes, up to the point where the ultimate bending moment is reached.

The difference between the calculated numerical results and the experimental one [

27] is around 30%, while in comparison with other researchers’ numerical results [

3], the difference is 3–9%, depending on the type of box girder and calculation software.

The ultimate bending moment (Mult) calculated using the Femap NX Nastran program (implicit solver) is higher for all three box girders compared to the Mult value obtained by other researchers/software.

The ultimate bending moment (Mult) calculated using the LS-Dyna program (explicit solver) is similar to the results of other researchers for models H300 and H400 (between the dispersion interval formed by the curves for ISSC-MIN and ISSC-MAX), while for model H200, the value is slightly below the average value of other researchers within the dispersion interval.

The ultimate bending moment (

Mult) calculated using the progressive collapse analysis method based on the Smith approach agrees well for model H400 and for model H300, while the results for the model H200 are around 29% above values obtained by numerical NLFEM methods. The definition of the load–end shortening curves has a great influence on the results obtained with the Smith method. Results obtained with the Smith method depend on the formulation of the load–end shortening curves (

σ-ε curves) [

2,

9,

34,

35]. The formulation of the used load–end shortening curves, based on IACS CSR [

2], is more appropriate for stiffeners with a larger effective length, which is presented in the H400 model; therefore, the result for this model is, as expected, more precise (−1.1% compared to ISSC-mean). Also, the Smit method is not fully appropriate for use for a small cross-section with a relatively high extent of hard corners.

Also differences between results obtained using a Smith-based method are identified if we compare the Smith method (HullColl) and Smith (UNIZAG) due to different definitions of σ-ε curves.

The results in

Table 2 in (10), which used Ansys APDL [

3] (solid elements), were excluded from the average results (given in ISSC-mean results) to make the NLFEM results using shell elements more comparable. Compared to the use of shell elements, the use of solid elements in this example overestimates the maximum ultimate moment. The difference compared to shell element calculations was that, for solid elements, not only was the plate imperfection mode used, but also the trilinear stress–strain curve, for both materials. However, as underlined in [

3], it has not been possible to quantifiably explain this difference in the results of shell and solid element calculations. All details can be found in the ISSC report [

3].

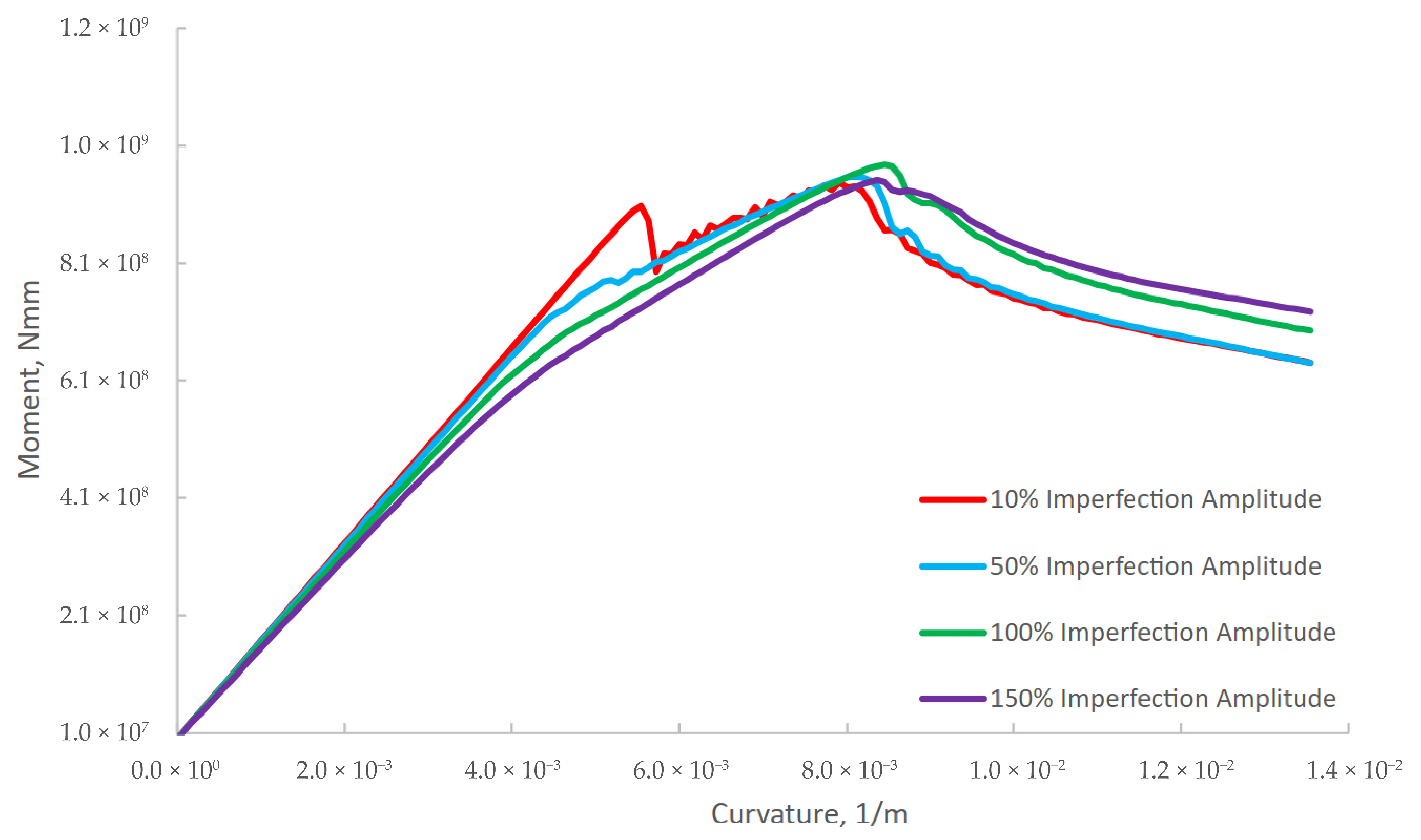

4.3. The Effect of Initial Geometric Imperfections

The present research investigated the effect of the amplitude and direction of initial geometric imperfections (IGIs) on the ultimate bending moment calculated using both methods (FEMAP/NX Nastran and LS-Dyna). A comparison of the ultimate bending moment

Mult obtained for all three models using both methods (FEMAP/NX Nastran, LS-Dyna) in the case without IGIs (geometrically ideal model) and with IGIs (100% of amplitude) as described in Ch 3.3. is presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The IGIs have the biggest impact on the vertical bending moment in the case of the most rigid model, H200 (38.4%). Without implementing the initial geometric imperfections, model H200 has an unrealistically high value for vertical bending moment. In the case of the other two models, IGIs have a minor impact (around 3%) on the value of the ultimate vertical bending moment.

Furthermore, the influence of the initial geometrical imperfection amplitude size on the value of the vertical bending moment in the case of the model H300, calculated using the software program LS-Dyna, was also investigated. The relation between IGI amplitude and vertical bending moment is presented in

Figure 16 and

Table 5, where the initial value of imperfection amplitude was 100% (according to [

3]) used for all three models (H200, H300, H400), as described in Chapter 3.3. Every amplitude component for all three types of implemented initial geometrical imperfection (AI, AII, AIII) is varied: 10%, 50%, 100%, and 150%.

It can be concluded that the amplitude of the initial geometrical imperfections has a very low impact (up to 3%) on the calculated vertical bending moment for the H300 model. Additionally, further research is needed to understand why an amplitude of 100% yields the highest results compared to smaller (50%) and larger (150%) amplitudes.

5. Conclusions

This study analyses the longitudinal ultimate strength of a thin-walled steel structure designed as a box girder, which simulates a ship hull. The ultimate strength of the longitudinal hull girder is determined by the maximum internal vertical bending moment, known as the ultimate vertical bending moment. The analysis was conducted using both an analytical incremental–iterative method, known as the Smith method and a numerical approach using the nonlinear finite element method (NLFEM). The results are significantly influenced by multiple parameters, including material properties, boundary conditions, loading type, finite element formulation, solver choice, and the implementation of initial geometric imperfections (IGIs).

The analysis was conducted using three models of stiffened box girders of varying transverse frame spacing and overall length. All models had the same material properties. The analysis showed that under vertical bending moment loading, the yielding of the deck longitudinal stiffeners occurs first, followed by the deck plating taking over the load. As the load increases, yielding of the plating occurs, eventually leading to the plasticization of the entire deck and a significant part of the box section.

The obtained ultimate vertical bending moment results were compared with the experiment [

27] and with those from other numerical analyses [

3]. The difference between the obtained results and those from other numerical calculations [

3] is between 3 and 9%, depending on the girder model and the software package used. The box girder benchmark study shows that when the problem is precisely defined, NLFEM can produce consistent results for a hull girder ultimate strength capability. From the presented NLFEM analyses the deviation of predicted ultimate bending moments results falls within the IACS CSR [

2] partial safety factor for strength prediction uncertainty (γₘ = 1.1).

However, the difference between the experimental results from [

4] and average NLFEM analysis is up to 30%, where numerical results yielded a smaller ultimate bending moment value. The large discrepancy may be due to experimental setup factors such as the boundary conditions, load implementation, or measurement techniques used during the experiment, but this assumption cannot be validated. It should also be pointed out that the use of an idealized bi-linear strain–stress curve can also be a cause of discrepancy between numerical and experimental results.

Additionally, a comparison between models with and without IGIs was conducted. The results indicated that the impact on the ultimate vertical bending moment in slender models (H300 and H400) was relatively small, at approximately 3%. In contrast, the influence on the more rigid H200 model was significantly greater, reaching 38%. It can be concluded that for the more rigid model (H200), it is obligatory to implement IGIs in the numerical calculation; otherwise, the results for the hull girder ultimate bending capacity will be overestimated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and J.A.; methodology, M.T. and J.A.; software, M.T., S.R. and P.P.; validation, M.T. and J.A.; formal analysis, M.T.; investigation, M.T. and J.A.; resources, M.T., J.A.; data curation, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, J.A.; visualization, P.P.; supervision, S.R. and J.A.; project administration, J.A.; funding acquisition, J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the funds of the European Union (Next Generation EU) as part of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021–2026 (NPOO), through the institutional project of University of Zagreb, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Naval Architecture “Advanced methods for management of ship maintenance-NEURON-B” approved by the Ministry of Science, Education and Youth (component C3.2., source 581).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IGI | Initial geometric imperfections |

| ISSC | International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress |

| NLFEM | Nonlinear finite element method |

| UNIZG | University of Zagreb |

References

- Kitarović, S. Analysis of Longitudinal Ultimate Load-Capacity in Concept Synthesis of Thin-Walled Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Naval Architecture, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The International Association of Classification Societies. Common Structural Rules for Bulk Carriers and Oil Tankers; IACS: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes Soares, C.; Garbatov, Y. (Eds.) ISSC 2015. Technical Committee III.1. Ultimate strength. In Proceedings of the 19th International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress, Cascais, Portugal, 7–10 September 2015; CRC Press: Boc Raton, FL, USA, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mirek, L.K.; Philippe, R. (Eds.) ISSC 2018. Technical Committee III.1. Ultimate strength. In Proceedings of the 20th International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress, Liege, Belgium, 9–14 September 2018; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaozhi, W.; Neil, P. (Eds.) ISSC 2022. Technical Committee III.1. Ultimate strength. In Proceedings of the 21st International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11–15 September 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wenwei, W.; Jun, D. (Eds.) ISSC 2025. Technical Committee III.1. Ultimate strength. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress, Wuxi, China, 22–26 September 2025; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.S. Influence of local compressive failure on ultimate longitudinal strength of a ship’s hull. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Practical Design in Shipbuilding, Tokyo, Japan, 18–20 October 1977; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ogawa, H.; Tatsumi, A.; Fujikubo, M. Analysis method of ultimate hull girder strength under combined loads. Ships Offshore Struct. 2015, 10, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikubo, M.; Tatsumi, A. Progressive collapse analysis of a container ship under combined longitudinal bending moment and bottom local loads. In Progress in the Analysis and Design of Marine Structures; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, O.F.; Paik, J.K. Ship Structural Analysis and Design; The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DNV. Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis of Hull Girder Collapse of a Tanker; Technical report No. 2004–0505; DNV: Oslo, Norway, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Z.; Yao, T.; Iijima, K.; Fujikubo, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Okazawa, S.; Yao, T. Collapse behaviour of ship hull girder of bulk carrier under alternative heavy loading condition. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Second International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Rhodes, Greece, 17–22 June 2012; International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Amlashi, H.K.; Moan, T. Ultimate strength analysis of a bulk carrier hull girder under alternate hold loading condition–a case study: Part 1: Nonlinear finite element modelling and ultimate hull girder capacity. Mar. Struct. 2008, 21, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Moan, T. Ultimate strength of a capesize bulk carrier in hogging and alternate hold loading condition. In Proceedings of the ASME 2010 29th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering. American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, Shanghai, China, 6–11 June 2010; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 441–449. [Google Scholar]

- Darie, I.; Roerup, J.; Wolf, V. Ultimate strength of a cape size bulk carrier under combined global and local loads. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Practical Design of Ships and Other Floating Structures PRADS2013, Changwon, Republic of Korea, 20–25 October 2013; pp. 1173–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Y.; Takami, T. Model Test on the Ultimate Longitudinal Strength of a Damaged Box Girder. In Analysis and Design of Marine Structures; Guedes Soares, C., Das, P.K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2015; pp. 435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Saad-Eldeen, S.; Garbatov, Y.; Guedes Soares, C. Ultimate strength of a box girder with a large opening subjected to flooding and bending loads. In Towards Green Marine Technology and Transport; Guedes Soares, C., Dejhalla, R., Pavletic, D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2015; pp. 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi, A.; Fujikubo, M. Finite element analysis of longitudinal bending collapse of container ship considering bottom local loads. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 35th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering. American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, Busan, Republic of Korea, 19–24 June 2016; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fujikubo, M.; Tatsumi, A. Ultimate strength of ship hull girder under combined longitudinal bending and local loads. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Structural Safety and Reliability of Ships, Offshore & Subsea Structures (SAROSS2016), Glasgow, UK, 15–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental evaluation of the ultimate bending moment of a box girder. Mar. Syst. Ocean Technol. 2004, 1, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental evaluation of the behaviour of a mild steel box girder under bending moment. Ships Offshore Struct. 2008, 3, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C. Experiments on Three Mild Steel Box Girders of Different Spans Under Pure Bending Moment. In Analysis and Design of Marine Structures; Guedes Soares, C., Romanoff, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2013; pp. 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental analysis of the effect of the frame spacing variation on the ultimate bending moment of box girders. Mar. Struct. 2014, 37, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental evaluation of the ultimate bending moment of a slender thin-walled box girder. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2015, 137, 021604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad-Eldeen, S.; Garbatov, Y.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental assessment of the ultimate strength of a box girder subjected to severe corrosion. Mar. Struct. 2011, 24, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Chen, B.-Q.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Li, Z.-J.; Hu, J.-J.; Guedes Soares, C. Experimental and numerical investigation on the ultimate strength of a ship hull girder model with deck openings. Mar. Struct. 2022, 83, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, J.M.; Guades Soares, C. Tests on ultimate strength of hull box girders made of high tensile steel. Mar. Struct. 2009, 22, 770–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estefen, S.F.; Chujutalli, J.H.; Guades, S.C. Influence of geometric imperfections on the ultimate strength of the double bottom of a Suezmax tanker. Eng. Struct. 2016, 127, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Soliman, M. Sensitivity of ship hull reliability considering geometric imperfections and residual stresses. Struct. Saf. 2025, 114, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, M.J.; Guades, S.C. Approximate load shortening curves for stiffened plates under uniaxial compression. In Integrity of Offshore Structures—5; Faulkner, D., Cowling, M.J., Incecik, A., Das, P.K., Eds.; EMAS: Warley, UK, 1993; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, J.; Nam, J.M.; Ha, T.B. Slenderness ratio distribution and load-shortening behaviors of stiffened panels. Mar. Struct. 2012, 26, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, J.; Kitarović, S.; Bičak, M. IACS Incremental-iterative method in progressive collapse analyses of various hull girder structures. Brodogradnja 2014, 65, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kitarović, S.; Žanić, V.; Andrić, J. Progressive collapse analyses of stiffened box-girders submitted to pure bending. Brodogradnja 2013, 64, 437–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kitarović, S.; Andrić, J.; Pirić, K. Hull girder progressive collapse analysis using IACS prescribed and NLFEM derived load-end shortening curves. Brodogradnja 2016, 67, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bužančić Primorac, B.; Parunov, J. Probabilistic Models of Ultimate Strength Reduction of Damaged Ship. Trans. FAMENA 2015, 39, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional view of H200, H300, and H400 box girder models.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional view of H200, H300, and H400 box girder models.

Figure 2.

Cross-section of a box girder with specified dimensions.

Figure 2.

Cross-section of a box girder with specified dimensions.

Figure 3.

Side view of a box girder.

Figure 3.

Side view of a box girder.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal view of the box girder in the experiment setup.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal view of the box girder in the experiment setup.

Figure 5.

Model H300 with the presentation of plate thickness (in mm).

Figure 5.

Model H300 with the presentation of plate thickness (in mm).

Figure 6.

Initial geometrical imperfections: type I (left), type II, and type III (right).

Figure 6.

Initial geometrical imperfections: type I (left), type II, and type III (right).

Figure 7.

Implementation of initial geometrical imperfections in FEM model: (a) type I; (b) type II; (c) type III; (d) superposition of all three types.

Figure 7.

Implementation of initial geometrical imperfections in FEM model: (a) type I; (b) type II; (c) type III; (d) superposition of all three types.

Figure 8.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model before collapse with LS-Dyna.

Figure 8.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model before collapse with LS-Dyna.

Figure 9.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model at time of collapse with LS-Dyna.

Figure 9.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model at time of collapse with LS-Dyna.

Figure 10.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model in post-collapse phase with LS-Dyna.

Figure 10.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H300 model in post-collapse phase with LS-Dyna.

Figure 11.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H200 model at time of collapse.

Figure 11.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H200 model at time of collapse.

Figure 12.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H400 model at time of collapse.

Figure 12.

Von Mises stresses and deformations for the H400 model at time of collapse.

Figure 13.

Comparison of results for H200 model [

3,

27].

Figure 13.

Comparison of results for H200 model [

3,

27].

Figure 14.

Comparison of results for H300 model [

3,

27].

Figure 14.

Comparison of results for H300 model [

3,

27].

Figure 15.

Comparison of results for H400 model [

3,

27].

Figure 15.

Comparison of results for H400 model [

3,

27].

Figure 16.

Influence of initial geometrical imperfection amplitude on Mult for model H300.

Figure 16.

Influence of initial geometrical imperfection amplitude on Mult for model H300.

Table 1.

Lengths of models and frame dimensions.

Table 1.

Lengths of models and frame dimensions.

| Model Type | Model Length

L (mm) | Transverse Frame Spacing, a (mm) | Transverse Frame Type (mm) | Number of Transverse Frames |

|---|

| H200 | 100 + 4 × 200 + 100 = 1000 | 200 | L50 × 20 × 6 | 5 |

| H300 | 100 + 3 × 300 + 100 = 1100 | 300 | L50 × 20 × 6 | 4 |

| H400 | 100 + 3 × 400 + 100 = 1400 | 400 | L50 × 20 × 6 | 4 |

Table 2.

Comparison of results from ISSC benchmark study [

3] and those obtained in UNIZG study.

Table 2.

Comparison of results from ISSC benchmark study [

3] and those obtained in UNIZG study.

| Method | H200

Mult (MNm) Difference (%) | H300

Mult (MNm) Difference (%) | H400

Mult (MNm) Difference (%) |

|---|

| Experiment [4] | 1.526 | | 1.269 | | 1.026 | |

| (1) Trident/VAST [3] | 1.139 | 0.0% | 0.958 | −1.1% | 0.863 | 3.0% |

| (2) Ansys Workbench [3] | 1.134 | −0.4% | 0.947 | −2.3% | 0.835 | −0.4% |

| (3) Abaqus–Riks [3] | 1.139 | 0.0% | 0.944 | −2.6% | 0.823 | −1.8% |

| (4) Ansys APDL [3] | 1.119 | −1.8% | 0.956 | −1.3% | 0.783 | −6.6% |

| (5) Ansys APDL [3] | 1.154 | 1.3% | 0.969 | 0.0% | 0.844 | 0.7% |

| (6) LS–Dyna [3] | 1.170 | 2.7% | 1.015 | 4.7% | 0.880 | 5.0% |

| (7) Abaqus–Riks [3] | 1.134 | −0.4% | 0.961 | −0.8% | 0.836 | −0.2% |

| (8) Femap/NX Nastran [3] | − | | 1.011 | 4.3% | 0.850 | 1.4% |

| (9) Abaqus–Newton–Raphson [3] | 1.120 | −1.7% | 0.958 | −1.1% | 0.824 | −1.7% |

| (10) Ansys APDL [3] (solid FE) | 1.651 | 45.0% | − | | 1.091 | 30.2% |

| (11) Smith method (HullColl) [3] | 1.291 | 13.3% | 1.175 | 21.3% | 0.913 | 8.9% |

|

ISSC-mean (results from 1÷9)

| 1.139 | 0.0% | 0.969 | 0.0% | 0.838 | 0.0% |

|

Standard deviation (results from 1÷9)

| 0.016 | | 0.025 | | 0.026 | |

|

ISSC-MIN

| 1.123 | −1.4% | 0.944 | −2.6% | 0.812 | −3.1% |

|

ISSC-MAX

| 1.154 | 1.3% | 0.993 | 2.5% | 0.863 | 3.0% |

|

Smith (UNIZG)

| 1.382 | 21.3% | 1.075 | 10.9% | 0.829 | −1.1% |

|

FEMAP/NX Nastran (UNIZG)

| 1.264 | 11.0% | 1.104 | 13.9% | 0.927 | 10.6% |

|

LS-Dyna (UNIZG)

| 1.066 | −6.4% | 0.978 | 0.9% | 0.826 | −1.4% |

Table 3.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with/without IGIs-FEMAP/NX Nastran.

Table 3.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with/without IGIs-FEMAP/NX Nastran.

| Model | Mult Without IGI, (MNm) | Mult-IGI—100% Amplitude, (MNm) | Difference

(%) |

|---|

| H200 | 1.546 | 1.264 | −22.3 |

| H300 | 1.082 | 1.104 | 1.99 |

| H400 | 0.904 | 0.927 | 2.48 |

Table 4.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with/without IGIs-LS-Dyna.

Table 4.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with/without IGIs-LS-Dyna.

| Model | Mult Without IGI, (MNm) | Mult-IGI—100% Amplitude, (MNm) | Difference (%) |

|---|

| H200 | 1.479 | 1.066 | −38.4 |

| H300 | 0.992 | 0.978 | −1.43 |

| H400 | 0.801 | 0.826 | 3.03 |

Table 5.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with respect to IGI amplitude-H300.

Table 5.

Comparison of ultimate bending moment (Mult) for models with respect to IGI amplitude-H300.

| IGI Amplitude | Mult [MNm] | Variation [%] |

|---|

| 100% | 0.978 | - |

| 10% | 0.946 | −3.27 |

| 50% | 0.958 | −2.04 |

| 150% | 0.951 | −2.76 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).