1. Introduction

When a vessel navigates in a straight line under conditions with oblique flow, the combined influence of the propeller’s wake can create significant challenges for steering control. By examining the hydrodynamic characteristics of the rudder and stern at various steering angles and oblique flow angles, ships can adjust their control systems effectively in response to adverse sea conditions. These adjustments lead to improved steering margins, enhanced course stability, reduced energy consumption of the steering gear, and ultimately lower overall shipping costs.

In early research, Meng studied the impact of oblique flow on propeller operation. His findings indicated that oblique flow leads to pronounced asymmetry in blade surface pressure distribution and a noticeable spatial shift in the propeller’s trailing vortex [

1].

Boswell and Jessup investigated the force conditions on single-blade propellers with various oblique angles, obtaining experimental values for the pressure distribution on the blade surface [

2,

3]. Yang et al. conducted numerical simulations of ship/propeller/rudder interactions using CFD methods, revealing that stern wake causes circumferential velocity non-uniformity in the propeller and significant pulsation amplitude in the lift coefficient [

4]. Building upon previous work, Dubbioso et al. investigated the single-blade moment and pressure of a four-bladed propeller under high incidence angles in oblique flow conditions [

5,

6].

Hu et al. conducted numerical simulations of the interaction between propeller wake vortex and rudders in oblique flow, proposing that a secondary vortex forms at the rudder’s leading edge, resulting in significant fluctuations in the amplitude of lateral forces on the rudder [

7]. Building on the preceding foundation, Zhang et al. systematically analyzed the coupling mechanism between propeller wake vortex and rudder surface pulsating pressure under oblique flow conditions using Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and sliding mesh technology. They concluded that the pulsating pressure on the rudder’s leeward side exhibits weaker correlation with blade frequency compared to the windward side, and the hub vortex on the leeward surface also undergoes displacement [

8]. Krasilnikov numerically simulated the pressure distribution of the DTMB4679 propeller blade in oblique flow using the CFD viscous flow method [

9]. Gaggero compared the hydrodynamic performance of propellers in oblique flow using two viscous flow methods based on Krasilnikov’s research, and verified that Krasilnikov’s method yields more accurate results [

10]. Chang conducted a numerical analysis of the unsteady hydrodynamic performance of a propeller in oblique flow and verified that, when the advance velocity coefficient is constant, the hub vortex exhibits a certain degree of displacement under the influence of oblique flow [

11]. Zhang conducted numerical simulations of the hydrodynamics of a stern propeller in oblique flow. Under oblique flow conditions, the tip vortex trajectory of the propeller tilts toward the oblique flow direction, enhancing its coupling with the hub vortex. He [

10] investigated methods for predicting the unsteady hydrodynamic performance of paddle-rudder systems, proposing a coupled paddle-rudder solution framework based on delayed detached eddy simulation (DDES) [

12]. This approach provides a suitable method for high-accuracy, rapid assessment of vessel maneuverability. FELLI M, FALCHI M [

13,

14] revealed that vortex-rudder interaction significantly intensifies as the oblique flow angle increases. When the oblique flow angle increases from 0° to 15°, the maximum pulsation pressure amplitude on the rudder surface increases significantly. Concurrently, the vortex system’s deflection angle increases, intensifying the coupling between tip vortex and hub vortex, thereby generating cross-beam vortex interference. Additionally, they studied the propeller wake evolution mechanisms in oblique flow conditions in 2018. In this study, the wake flow past an isolated propeller operating in oblique flow conditions is investigated experimentally.

In recent years, Hu et al. conducted numerical simulations of vortex-rudder interactions in the wake of oblique-flow propellers. Results indicate that both the hydrodynamic coefficients of the propeller and rudder exhibit an increasing trend under oblique flow conditions [

15]. Li investigated the hydrodynamic performance and flow field characteristics of a ship’s stern propeller in oblique flow. A systematic analysis revealed that axial velocity increases on the side of the propeller’s centerline as the oblique flow angle increases [

16]. Zhang conducted a numerical analysis of the wake field of a duct propeller/propeller under small-angle oblique flow. As the oblique flow angle increases, the wake field exhibits a more pronounced influence from the angle of attack [

17]. Li investigated the effect of rudder control on propeller performance in oblique flow. The study revealed that as the oblique flow angle increases, the propeller’s thrust, torque, and lateral force all significantly increase. The introduction of rudder control can effectively reduce the propeller’s lateral force [

18]. Ji N investigated the effects of oblique flow on the ship–propeller–rudder system. The study demonstrated that vortex shedding on both sides behind the propeller exhibited increasingly pronounced separation as the oblique flow angle increased, while separation in the propeller-rudder system remained relatively weak [

19]. Koksal, CS; Aktas, B et al. Experimental assessment of hull, propeller, and the gate rudder system interaction in calm water and oblique waves [

20]. In 2023, Hou et al. conducted a two-dimensional study on the hydrodynamic performance of collaborative spoiled rudder. The study determined the optimal ranges of the rudder angle and the control angle of spoiler are determined [

21]. Wang et al. in 2023 revealed the numerical course-keeping tests of ONR tumblehome in waves with different rudder control strategies [

22]. Sun S et al. in 2023 investigated the effect of oblique flow on the load-carrying capacity of a four-screw ship. The results indicate that as the drift angle increases, the average axial load on the propeller shaft also increases with the drift angle [

23]. Wei, XX et al. in 2024 investigated the research on the hydrodynamic performance of propellers under oblique flow conditions. This study indicated that with the increase in oblique flow angles, the thrust, torque, and efficiency of the propeller show different increasing trends [

24].

Previous studies have primarily focused on the hydrodynamic characteristics of ships, propellers, and rudders under oblique flow or steering conditions. However, there has been limited consideration of the coupled interactions between oblique flow, steering, and the propeller–rudder system. This research computationally examines how the rudder force varies under different angles of oblique flow and steering, and it identifies the rudder stall angle. Additionally, the study analyzes how changes in oblique flow and rudder angles affect the axial velocity and vortex intensity behind the rudder. At large oblique flow or steering angles, counter-flow occurs in the axial velocity on the downwind side of the rudder behind the propeller. This results in the separation point advancing and the vortex structure becoming more complex. Such dynamics explain the fluctuations in rudder effectiveness due to the combined effects of high oblique flow and large steering angles. The distinctions from previous CFD analyses are clearly highlighted in this study.

This study builds on prior research by conducting a thorough numerical investigation into the hydrodynamic performance of rudders positioned behind propellers, specifically examining the combined effects of oblique flow angles and rudder angles. In

Section 2, we outline the research objectives and theoretical frameworks, which include parameterized modeling and turbulence equations.

Section 3 details the numerical methods and open-water validation processes, focusing on the selection of time steps and the verification of our models.

Section 4 explores the hydrodynamic characteristics, velocity fields, and the evolution of horizontal vortices associated with the rudder placed behind the propeller at various rudder angles. In

Section 5, we examine the hydrodynamic properties and flow field responses under different oblique flow angles.

Section 6 provides a systematic analysis of how hydrodynamic performance and flow field characteristics change due to the combined effects of oblique flow and rudder angles. Finally, the

Section 7 summarizes the key findings and contributions of this research.

5. Analysis on Hydrodynamic Characteristics of the Rudder Behind the Propeller at Different Oblique Flow Angles

5.1. Numerical Calculation of Hydrodynamic Performance of the Rudder Following the Propeller at Different Oblique Flow Angles

As shown in

Figure 8a, when the advance coefficient is constant, the rudder lift coefficient increases with the increase in oblique flow angle. Conversely, when the oblique flow angle is held constant, the rate of increase in the rudder lift coefficient decreases as the advance velocity coefficient increases.

As shown in

Figure 8b, when the advance coefficient is constant, the rudder drag coefficient exhibits an overall decreasing trend as the oblique flow angle increases. This reduction becomes more pronounced with larger angles (

β). Additionally, when

β is held constant, the decrease in the rudder drag coefficient is significantly more pronounced under light load conditions compared to heavy load conditions.

As shown in

Figure 8c, when the oblique flow angle is fixed, the rudder lift-to-drag ratio progressively increases as the advance coefficient rises, leading to enhanced steering performance. Conversely, when the advance coefficient is constant, the rudder’s lift-to-drag ratio also increases with the oblique flow angle, and this increase accelerates over time, indicating improved steering effectiveness.

Consequently, the combined effects of the oblique flow angle and the advance coefficient result in an overall decrease in both rudder lift and drag. However, the reduction in rudder lift is less significant than the reduction in rudder drag, which ultimately enhances the hydrodynamic characteristics of the rudder.

5.2. Analysis on the Axial Velocity of the Rudder Following the Propeller at Different Oblique Flow Angles

This study aims to investigate how different obliquity angles affect the hydrodynamic characteristics of a propeller–rudder system. Two operating conditions were selected for the analysis, with advance coefficients of

J = 0.3 and

J = 0.7. The variations in axial velocity of the propeller–rudder system, observed along the

Z-axis, are as follows (

Figure 9):

When the advance velocity J = 0.3, the velocity at the leading edges of the propeller and rudder gradually increases as the oblique flow angle increases. In contrast, when J = 0.7, while the velocity trends at the propeller and rudder leading edges are consistent with those observed at J = 0.3, a localized high-velocity zone emerges at the trailing edge of the rudder.

In summary, when the oblique flow angle (β) is between 0° and 9°, the deflection amplitude of the propeller wake is small, and the velocity difference between the leading and trailing edges of the rudder is negligible. However, when β ranges from 9° to 15°, the strong deflection of the propeller wake induces localized reverse flow on the control surfaces. This results in a significant increase in the velocity difference between the two sides of the rudder, which amplifies the pressure difference. Consequently, this enhances the lift generated by the rudder while reducing the rudder drag.

According to fluid dynamics mechanics, increasing the angle of oblique flow increases the pressure difference between the upper and lower surfaces of the rudder, resulting in greater lift. At the same time, the uneven distribution of axial velocity can shift the flow separation point on the rudder’s surface further back. This shift reduces the formation of vortex and the energy losses associated with separation, which consequently leads to lower drag.

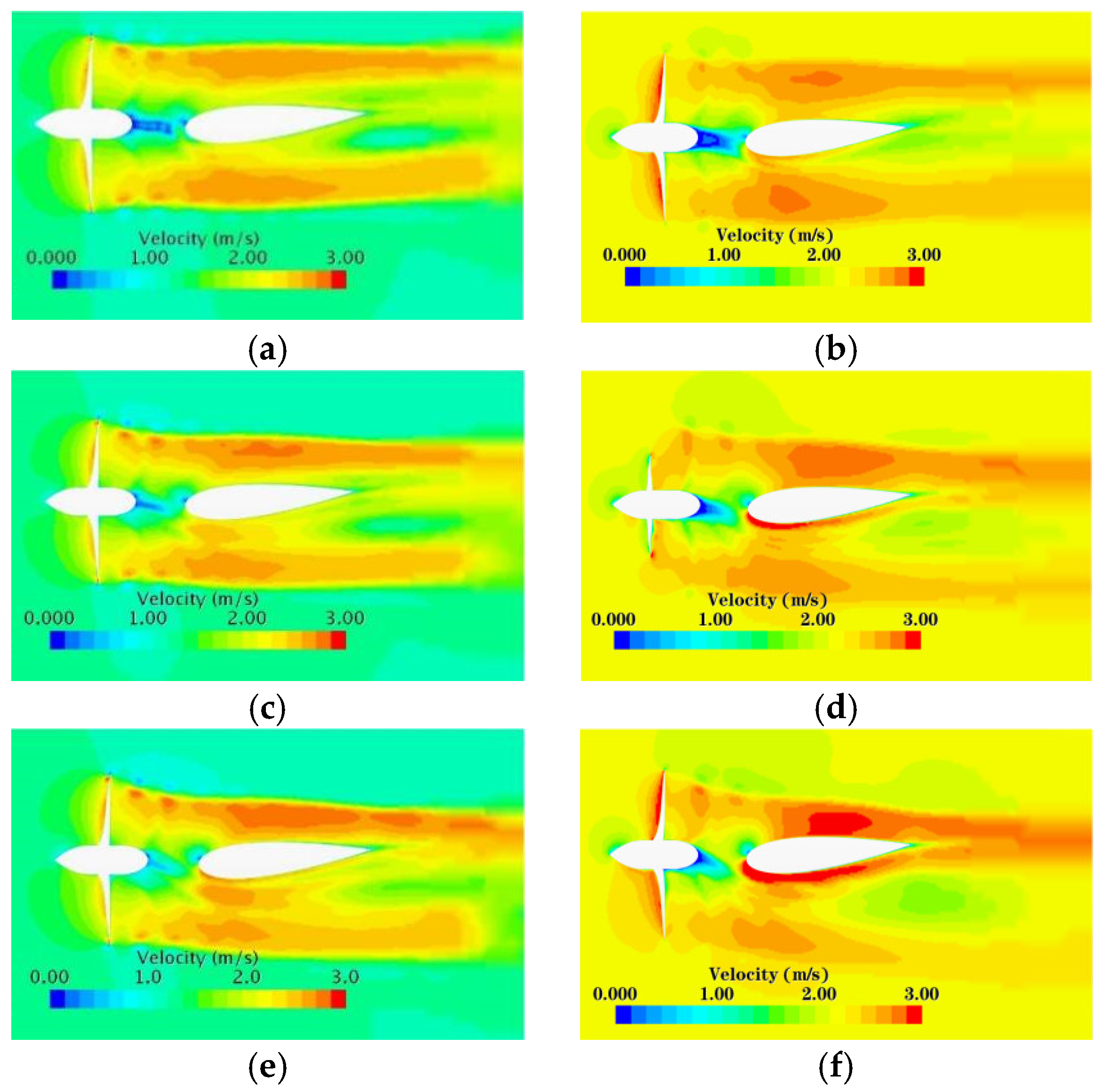

5.3. Analysis on the Horizontal Vortex Generation of the Rudder Following the Propeller at Different Oblique Flow Angles

When

β = 0°, the horizontal vortex distribution on both sides of the rudder behind the blade is stable and exhibits single symmetry. At high advance velocities, vortex dissipation occurs relatively quickly on both sides of the rudder. When

β = 3°, only local perturbations occur, with minor deflection of the wake and hub vortex behind the blade. When

β = 9°, vortex distribution shifts collectively under oblique flow guidance, with intermittent vortex shedding occurring on the downwind side. When

β = 15° and under light load conditions, the symmetric distribution of rudder vortex is disrupted. At

J = 0.7, a localized main vortex region appears on the downwind side. Simultaneously, the hub vortex shift significantly toward the trailing edge of the rudder. Under heavy load conditions, vortex dissipation behind the propeller slows as

β increases (see

Figure 10).

When δ = 0° and β = 0–15°, the wake behind the propeller undergoes significant deflection after being guided by the oblique flow, gradually inducing localized reverse flow in the rudder flow field. The difference between the velocity on the leeward side and that on the windward side of the rudder significantly increases. The intensity of the primary vortex on the leeward side surges dramatically, accompanied by a secondary vortex. Concurrently, the hub vortex shifts significantly toward the leeward side of the rudder, and vortex dissipation slows noticeably at low advance velocity.

Based on the principles of fluid dynamics, it can be concluded that an increased oblique angle alters the impact angle of the water flow on the propeller and rudder, intensifying flow separation on the rudder surface. On the leeward side, the separated flow forms larger-scale vortex, thereby increasing the intensity of the main vortex. Simultaneously, the unstable nature of the separated flow also facilitates the generation of secondary vortex.

6. Analysis on Hydrodynamic Characteristics of the Rudder Behind the Propeller Under the Coupling Effects of Oblique Flow and Steering

6.1. Numerical Analysis of Hydrodynamics at the Rudder Following the Propeller Under Oblique Flow and Steering

Most profile rudders demonstrate effective rudder angles of up to

δ = 35°. However, the rudder examined in this paper stalls at

δ = 40°. Therefore, angles beyond

δ = 40° will be excluded from the analysis of the hydrodynamic effects of rudder operation on the stern under various oblique flow angles. The case of axial flow at

β = 0° has already been studied. For this discussion, three oblique flow angles are selected:

β = 3°,

β = 9°, and

β = 15° (see

Figure 11).

When

β = 3° and

J remains constant, rudder lift and drag increase with increasing steering angle, with the rate of increase gradually accelerating. Conversely, when the steering angle is held constant, rudder lift and drag rise with an increasing velocity coefficient. However, both the lift coefficient and drag coefficient decrease as the velocity coefficient increases, with the rate of decrease slowing progressively as

J increases. Notably, at a steering angle of

δ = 35° and

J = 0.9, rudder lift experiences a slight decrease compared to when

δ = 25°, although the reduction in magnitude is smaller (see

Figure 12).

When

J is constant, both rudder lift and drag increase as the steering angle increases, with the rate of increase gradually accelerating. At a fixed steering angle, both rudder lift and drag rise as

J increases; however, their lift coefficient and drag coefficient decrease with increasing

J, and the rate of this decrease slows down as

J continues to rise. For a steering angle of

δ = 35° and

J = 0.9, the variation trend of rudder lift resembles that at

δ = 15°, showing a greater decrease compared to

δ = 25°. In contrast, rudder drag remains essentially consistent with the observed patterns at

J = 0.8 (see

Figure 13).

When β = 15°, the overall hydrodynamic performance of the rudder exhibits a similar trend to that at β = 9°. At δ = 25° and δ = 15°, the rudder lift coefficient is essentially comparable at J = 0.7. However, at δ = 35° and J = 0.9, both the rudder lift coefficient and drag coefficient decrease, with a greater reduction than under the β = 9° operating condition.

In summary, with the exception of

δ = 35°, the trends of lift and drag with respect to

β remain consistent across all control angles. At fixed control angles, both lift and drag increase as

β increases. Conversely, at a constant

β, the rate of increase in lift and drag accelerates as increasing

δ. However, at

δ = 35°, an increase in

β unexpectedly leads to a decrease in both lift and drag at

J = 0.9, causing a sharp decline in lift while drag decreases more gradually. The combined effects of oblique flow and rudder control result in the oblique flow angle changing the direction and velocity distribution over the rudder blade, which reduces its effective angle of attack. This complex wake weakens the pressure differential across the rudder surface, diminishing the rudder’s force and leading to stall, which can result in loss of control (see

Figure 14).

At three different oblique flow angles, the lift-to-drag ratio generally decreases gradually as the rudder angle increases. For the rudder angles of δ = 0° and δ = 5°, the lift-to-drag ratio progressively rises with increasing oblique flow angles. However, at other rudder angles, the overall variation in the lift-to-drag ratio is negligible. At the oblique flow angle of β = 3°, the lift-to-drag ratio with a rudder angle of δ = 0° is lower than that at δ = 5° and δ = 15°. For β = 9°, the lift-to-drag ratio at δ = 0° is generally lower than at δ = 5°, although it exceeds that of δ = 5° when J = 0.9. At β = 15°, the lift-to-drag ratio at δ = 0° shows a significant discontinuity as J increases, affecting the ratios at other rudder angles.

The lift-to-drag ratio at large rudder angles is generally lower than at small rudder angles. However, the overall values of lift and drag are higher at large angles compared to small ones. This difference is primarily due to the turbulent flow field that develops behind the rudder at larger steering angles. Primary and secondary vortices form more readily on the leeward side of the rudder, which intensifies the flow impact and increases friction against the blade. As a result, the pressure difference between the windward and leeward sides decreases, leading to reduced lift while drag continues to increase.

6.2. Analysis on Axial Velocity Distribution of the Rudder Following the Propeller Under Oblique Flow and Steering

To thoroughly examine the impact of rudder deflection on the hydrodynamic characteristics of the rudder wake under oblique flow conditions, we calculated the axial velocity distribution contour plots for four different rudder deflection angles:

δ = 5°,

δ = 15°,

δ = 25°, and

δ = 35°. These calculations were performed at oblique flow angles of

β = 3°,

β = 9°, and

β = 15°. The results are shown below (

Figure 15):

At

δ = 5° and

J = 0.5 operating conditions, the velocity on the leeward side of the rudder increases as the oblique flow angle increases. Additionally, both the velocity within the propeller wake field and the angular offset between the propeller’s hub velocity and the rudder also increase with the oblique flow angle. When the oblique flow angle remains constant, the axial velocity on both sides of the rudder is higher at a high pitch than at a low pitch. This results in a gradual disruption of the symmetry in the velocity distribution on both sides of the rudder blade (see

Figure 16).

When

J = 0.5 and

β = 15°, a localized high-velocity field forms at the leading edge on the leeward side of the rudder. Under light load conditions, this high-velocity zone gradually expands towards the tail of the rudder as the oblique flow angle increases. This zone eventually converges with the wake field generated by the propeller, while the angular offset between the velocity of the propeller hub and the rudder velocity increases (see

Figure 17).

For the heavy-load condition at

δ = 25°, the low-velocity flow field on the leeward side of the rudder gradually spreads outward from the trailing edge of the rudder blade toward the periphery. When

J = 0.9, both the diffusion velocity and the area of the high-velocity zone at the leading edge of the rudder blade, as well as the low-velocity zone at the trailing edge, increase with higher oblique flow angles. The peak velocity on the back surface of the rudder significantly rises, while the velocity variation on the windward side remains relatively smooth. This leads to a consistently increasing velocity difference between the two sides as the oblique flow angle increases (see

Figure 18).

Under full rudder heavy-load conditions with an angle of deflection (δ) of 35°, the low-velocity flow field on the leeward side of the rudder spreads outward from the tail section, accelerating its convergence with the wake field generated by the propeller. In contrast, under light-load conditions, the velocity distribution on both sides of the rudder blade shows significant asymmetry. This results in a reduced pressure differential across the blade and a decrease in rudder force.

The results indicate that the axial velocity behind the rudder is influenced by the coupling effect of the oblique flow angle and steering, which increases the asymmetry of velocity on both sides of the rudder blade. This results in a more complex and pronounced velocity difference. High-velocity fluid within the propeller wake, directed by the oblique flow, tends to shift more towards the downwind side of the rudder blade. This shift further exacerbates the velocity difference between the two sides of the rudder.

6.3. Analysis on the Distribution of Horizontal Vortex at the Rudder Following Propeller Under Oblique Flow and Steering

At

δ = 5°, flow separation on the rudder’s surface is relatively weak. The windward side of the rudder exhibits predominantly attached flow, while the leeward side generates only a thin boundary layer separation vortex. When the oblique flow angle is fixed, the horizontal vortex field of the propeller-rudder system dissipates less energy under heavy load conditions compared to light load conditions; however, the overall vortex field retains a “single-symmetric” structure (see

Figure 19 and

Figure 20).

At a deflection angle (

δ) of 15° under heavy-load conditions, the tail vortex of the propeller is reduced compared to a

δ of 5°. Additionally, the localized main vortex region at the trailing edge of the rudder blade gradually decreases. When the advance coefficient (

J) is 0.7, the main vortex zone on the leeward side of the rudder shifts position. However, there is no significant separation of the attached vortex, and no secondary vortex formation is triggered (see

Figure 21).

Under heavy-load conditions at a deflection angle of (

δ) of 25°, flow separation occurs on the surface of the rudder. On the leeward side of the rudder, the primary vortex divides into a main vortex and a secondary vortex, demonstrating vortex breakup. At the advance coefficient (

J) of 0.7, both the tip vortex and hub vortex of the propeller shift in the direction of the oblique flow. Meanwhile, the main vortex near the leading edge gradually dissipates, while the vortex intensity on the downwind side of the rudder progressively increases with an increase in angle (

β) (see

Figure 22).

When the rudder is set to a full angle of δ = 35° under heavy-load conditions, the low vortex region on the leeward side of the rudder gradually decreases. In contrast, the low vortex region on the leading edge surface shows significant adhesion, leading to more pronounced vortex separation. As the oblique flow at J = 0.7 exerts influence, the tip vortex, hub vortex, and leading edge vortex of the rudder gradually shift toward the trailing edge of the rudder blade. A distinct peak in vortex activity occurs at the trailing edge of the rudder blade, causing the vortex on the leading and trailing sides of the blade to gradually converge.

The results indicate that we can draw conclusions regarding the horizontal vortex behind the rudder. As the steering angle and the angle of oblique flow increase, we notice that the flow field around the rudder becomes more complex, and the phenomenon of flow separation is enhanced. Numerical simulation results show that a distinct boundary layer separation occurs on the leeward side of the rudder. At this stage, the separation point shifts forward, leading to an expansion of the separation zone. This separated flow generates large-scale vortex structures that significantly affect the performance of the rudder.

7. Conclusions

This study numerically investigates the coupled effects of oblique flow and rudder angle on the hydrodynamic performance of a rudder behind a propeller. The key finding is the identification of a transition in the dominant control mechanism: the rudder angle (δ) governs hydrodynamic performance at small oblique flow angles (β ≤ 3°), whereas the oblique flow angle (β) becomes the decisive factor at larger angles (β ≥ 9°). This mechanistic insight is critical for predicting and optimizing ship maneuvering in complex navigation scenarios.

Furthermore, the research highlights a significant risk under extreme conditions. The combination of a high oblique flow angle (β = 15°) and a large rudder angle (δ = 35°) induces severe “coupled interference”. This phenomenon is characterized by a highly asymmetric flow velocity distribution and the generation of complex vortex structures (including primary and secondary vortices) on the rudder’s leeward side. These flow dynamics ultimately precipitate a sharp decrease in lift coefficient and a markedly increased risk of rudder stall.

In summary, this work elucidates the critical interaction between oblique flow and steering, providing valuable theoretical insights and practical guidance for enhancing ship maneuvering stability and safety.

Future work will focus on the experimental validation of the complex vortex structures identified in this study using techniques such as PIV. Additionally, research will be extended to a broader range of propeller–rudder configurations to generalize the findings.