Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Heterogeneous USV-AUV Swarms Based on Dynamic Event Triggering

Abstract

1. Introduction

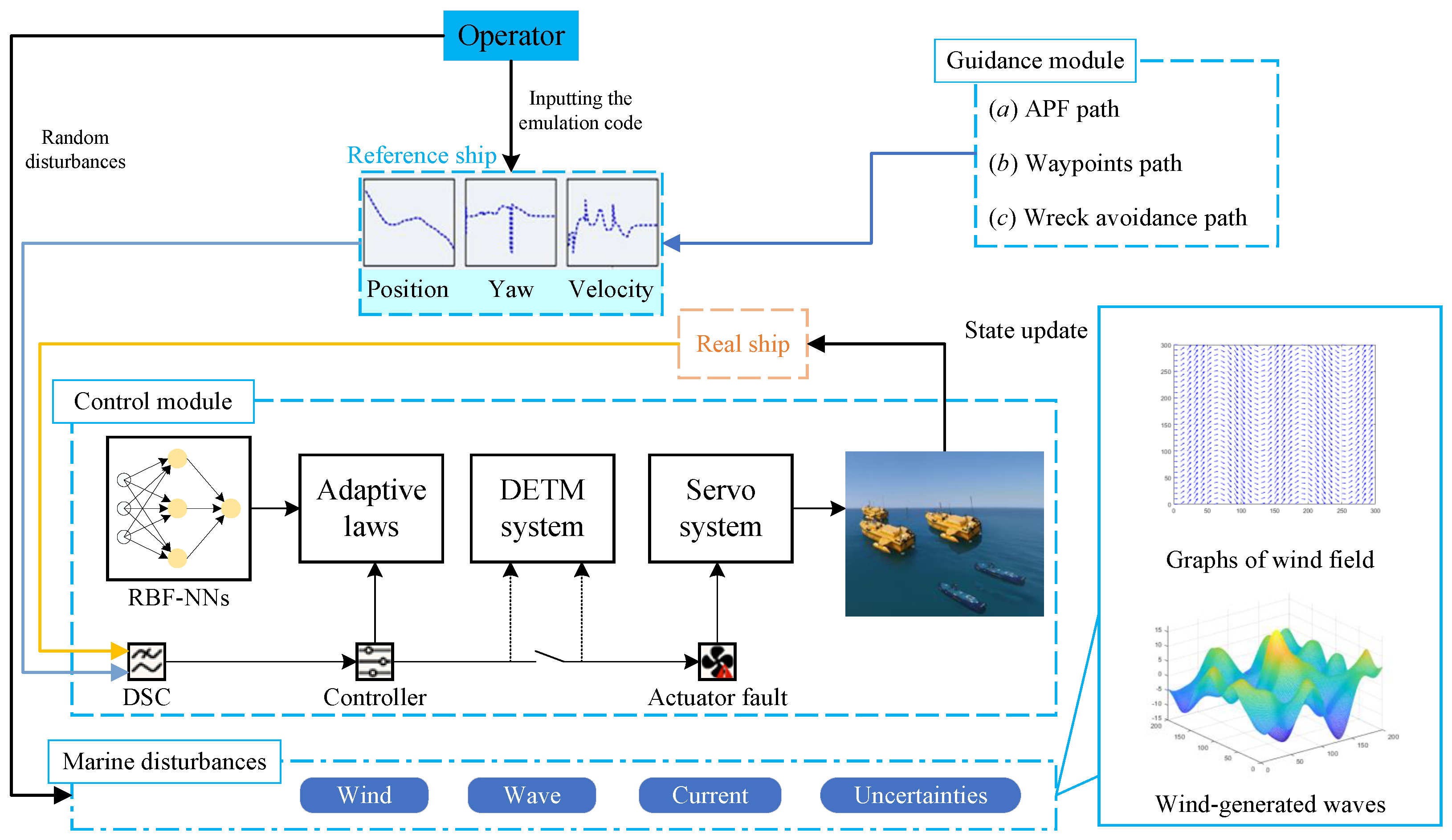

- Euler–Lagrange Modeling: This paper establishes a unified model capable of describing the dynamics of both USVs and AUVs. By parameterizing the unknown terms in the system, this paper lays down a foundation for the subsequent design of a general adaptive controller.

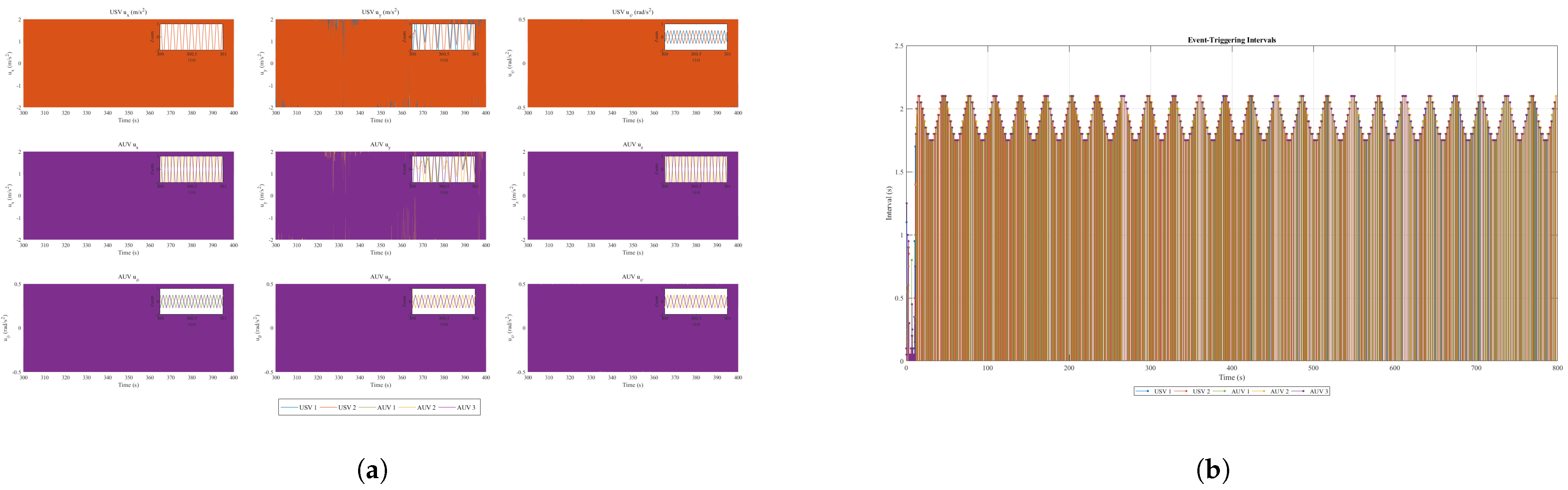

- DETM: To address the problem of limited underwater acoustic communication resources, this paper includes the design of a DETM for each agent. The triggering threshold of this mechanism is correlated with the dynamic formation error of the system, which can increase the communication frequency to ensure fast convergence when the error is large, and reduce communication to save energy when the system is stable, thereby achieving an intelligent trade-off between communication efficiency and control performance.

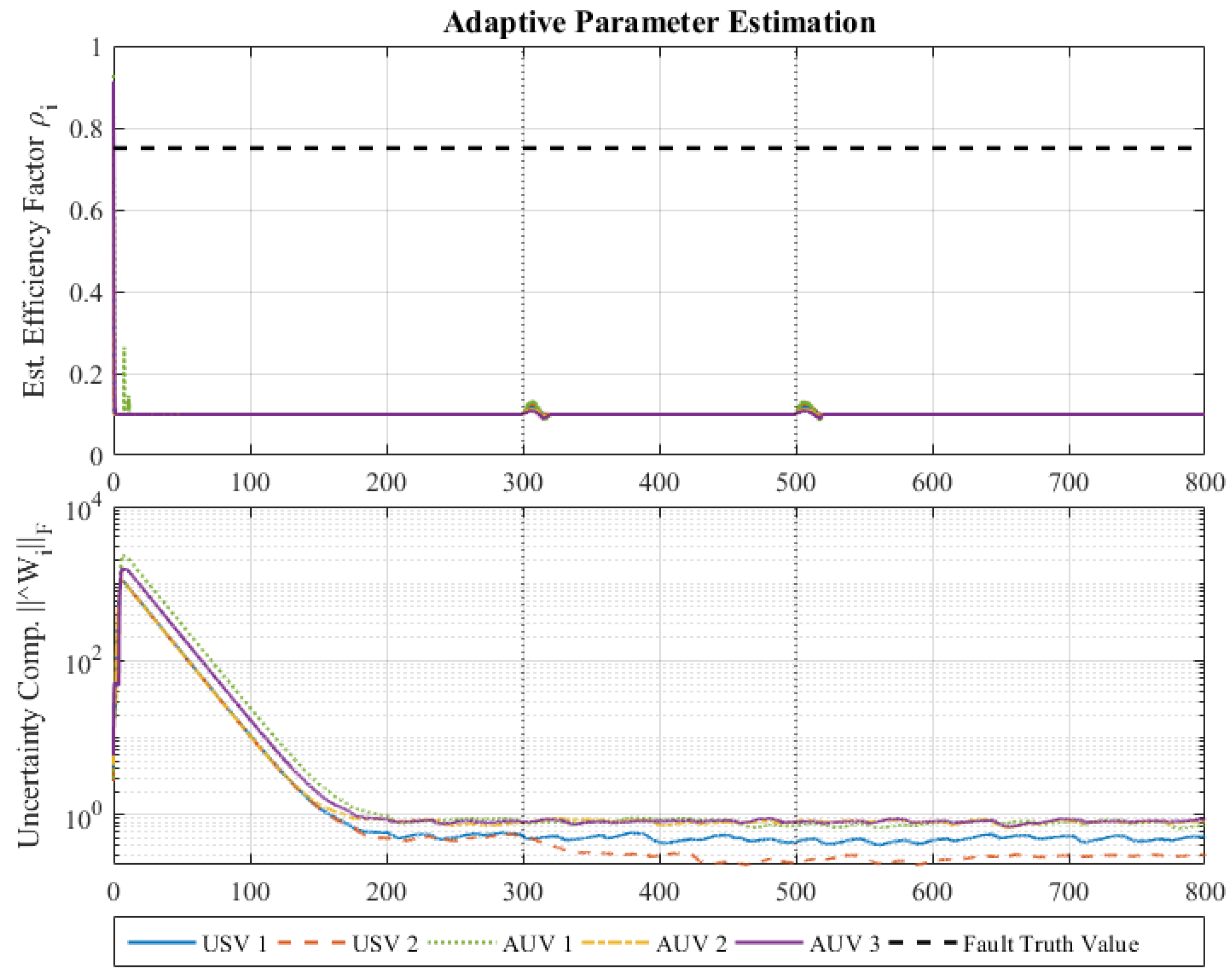

- Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Strategy: The controller incorporates adaptive laws, enabling it to provide an online estimate and compensate for unknown system parameters, external disturbances, and actuator faults caused by loss of effectiveness and bias. This ensures that the formation system can maintain stable performance in the face of internal faults and external uncertainties. Meanwhile, to handle time-varying communication delays, this paper incorporates delay terms into the stability analysis by constructing an appropriate Lyapunov–Krasovskii functional, ensuring the stability of the closed-loop system in the presence of delays.

2. System Modeling and Problem Description

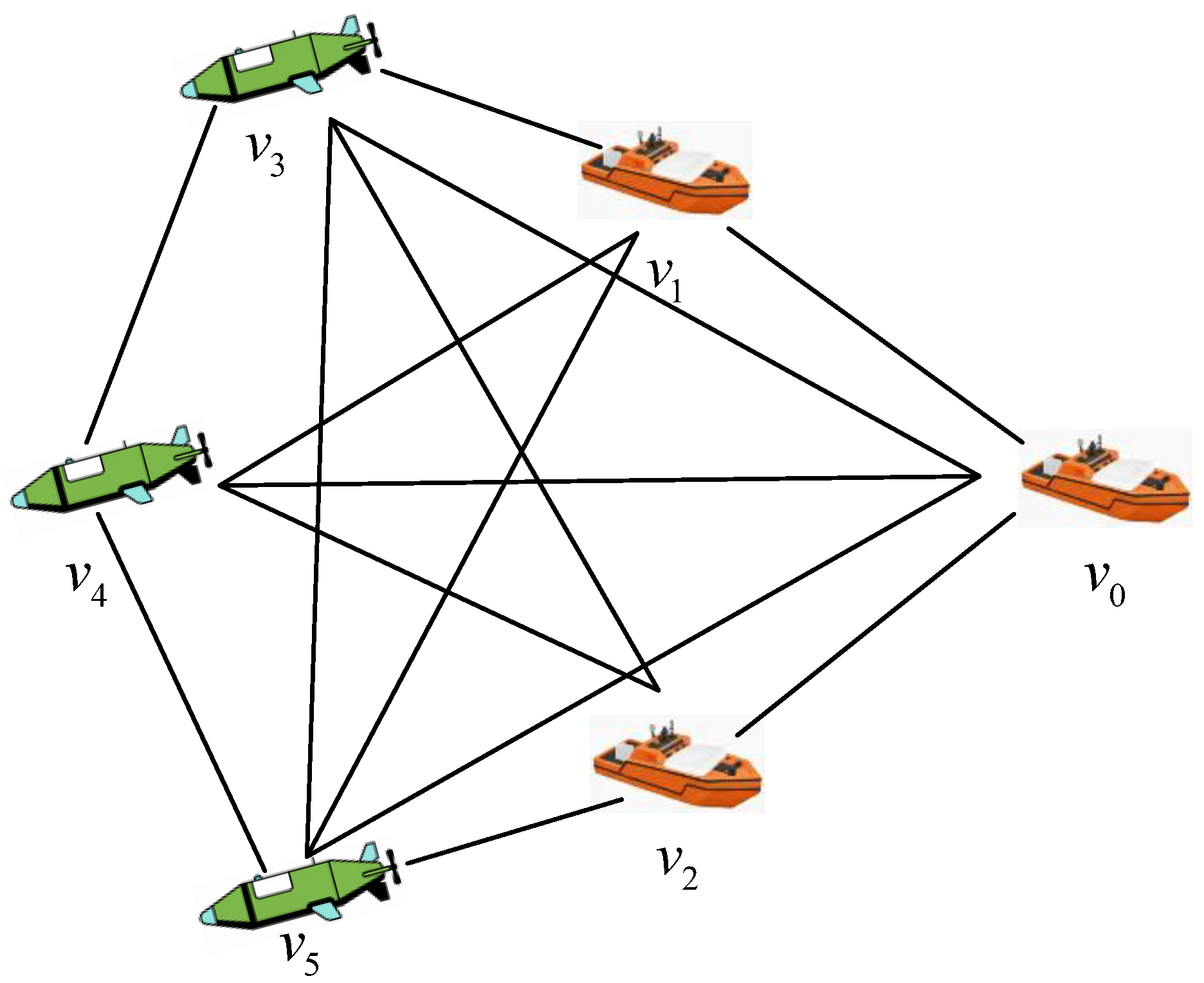

2.1. Graph Theory and Communication Topology

- Adjacency Matrix: The communication links between followers are characterized by a weighted adjacency matrix . The weight if and only if and ; otherwise, . This paper follows the convention that for all i.

- Navigation Matrix: The communication links from the leader to followers are described by a diagonal navigation matrix . If follower i can directly receive information from the leader, then ; otherwise, .

- Degree Matrix: The in-degree matrix of the follower network is a diagonal matrix , where each diagonal element is defined as follows:This element represents the total weight of information flows received by follower i from all other followers.

- Laplacian Matrix: The graph Laplacian matrix of the follower network is defined as follows:

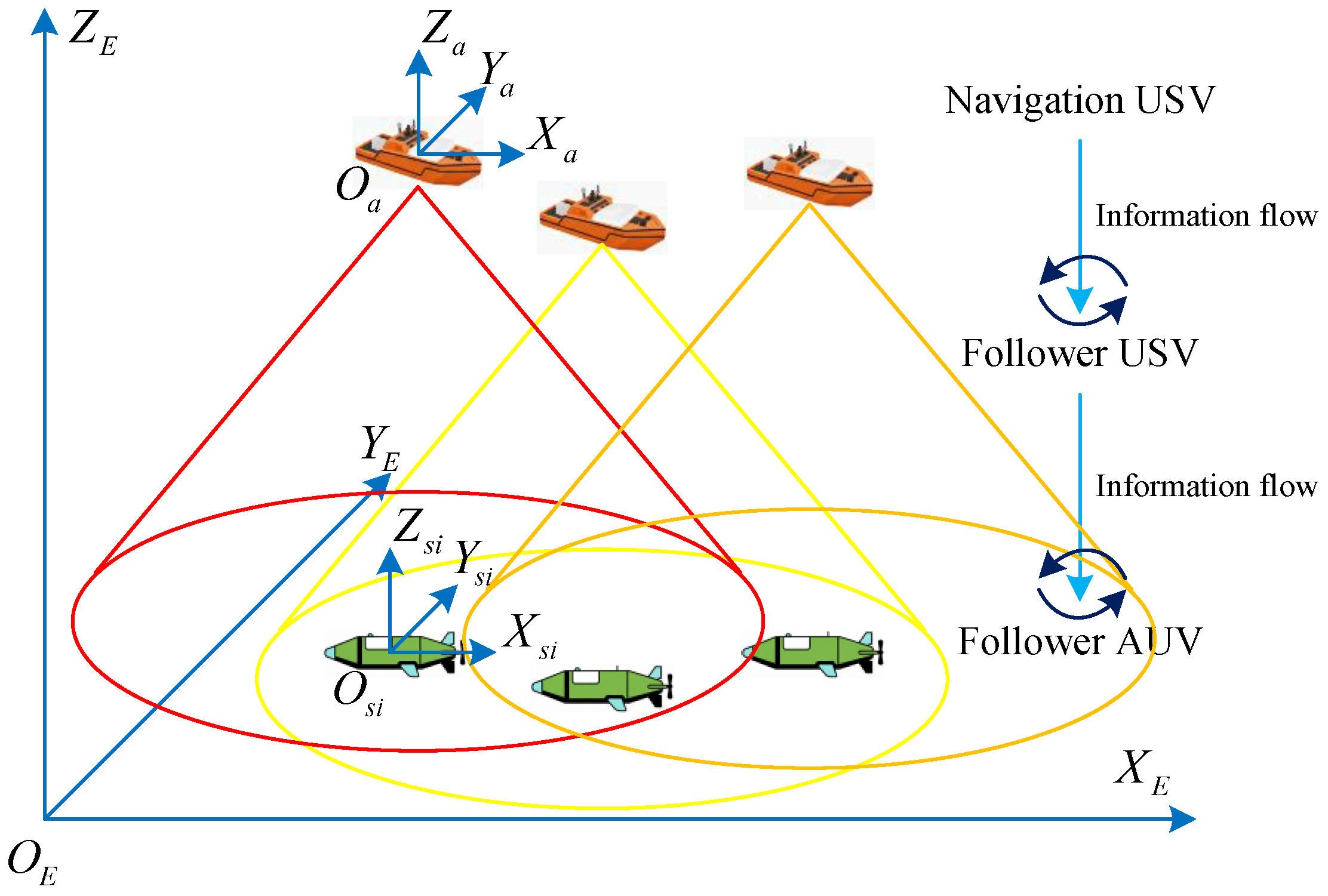

2.2. Heterogeneous Dynamic Models

- Dimension Reduction: USVs primarily move in the horizontal plane, so their model can usually be simplified to 3 DOF (surge , sway , yaw ), i.e., and . Their roll, pitch, and heave motions are generally treated as bounded disturbances.

- Restoring Force/Moment: For AUVs, the restoring force/moment term is crucial. It is determined by the positions of the center of gravity and center of buoyancy, and is key to maintaining attitude stability. For USVs, this term can usually be neglected in the horizontal-plane model.

- Inertia and Damping: AUVs are fully submerged in water, so their added mass effect and hydrodynamic damping are far more significant and complex than those of USVs floating on the water surface.

- External Disturbances: USVs are mainly affected by wind and waves, while AUVs are primarily influenced by ocean currents. The characteristics and models of these disturbances are completely different.

2.3. Actuator Faults and Communication Delays

- (1)

- Actuator Fault Model

- (2)

- Communication Delay Model

2.4. Formation Control Problem Modeling

- 1.

- The dynamics of each follower are described by the nonlinear Equation (5);

- 2.

- The actuators of each follower may suffer from unknown effectiveness loss and bias faults as shown in (8), with fault parameters satisfying Assumption 2;

- 3.

- Information interaction within the system is conducted through a time-varying communication topology that satisfies Assumption 1;

- 4.

- Information transmission between any two unmanned platforms involves time-varying bounded delays as described in (9) and (10), which satisfy Assumption 3.

3. Formation Control Method Design and Stability Analysis

3.1. Dynamic Event-Triggered Mechanism

- 1.

- When the system control error is large, the term dominates, making a relatively large negative number, and the threshold decreases rapidly. A smaller threshold means a lower tolerance for measurement errors, which will lead to more frequent event triggering, thereby providing the controller with more timely state information to suppress errors.

- 2.

- When the system tends to be stable and the control error becomes very small, , which will make . At this point, will gradually stabilize around . The threshold is relatively large at this time, allowing the measurement error to vary within a larger range, thus greatly reducing the communication frequency in the stable state and saving energy consumption.

- 3.

- The existence of the constant term ensures that the threshold has a positive lower bound even in the ideal case where the error is zero, which is crucial for avoiding the Zeno phenomenon.

3.2. Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Controller

3.2.1. Composite Error and Sliding Mode Surface Design

3.2.2. Uncertainty Handling and Function Approximation

3.2.3. Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control Law

3.3. Stability Analysis

4. Simulation

4.1. Conditions

- (1)

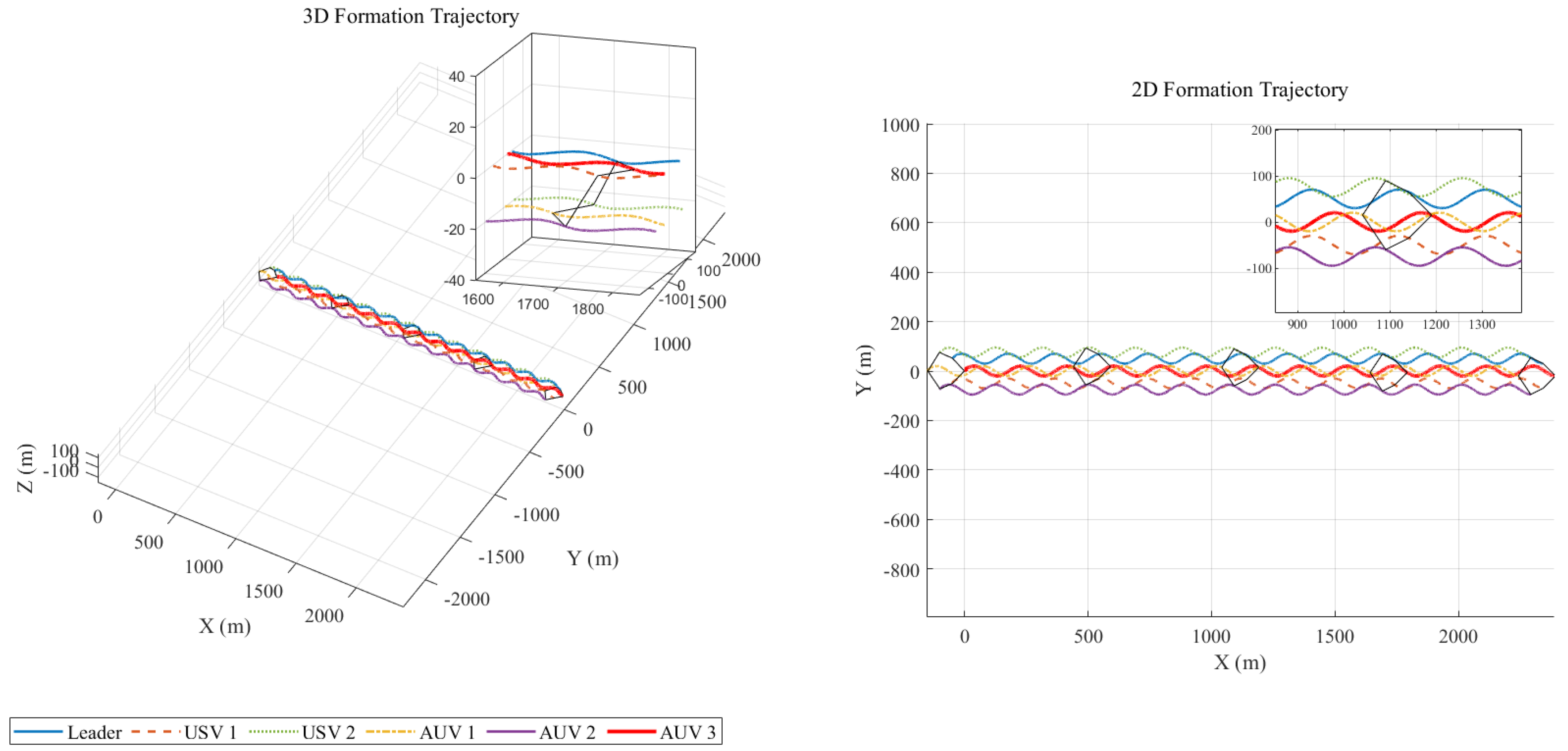

- Formation System Configuration

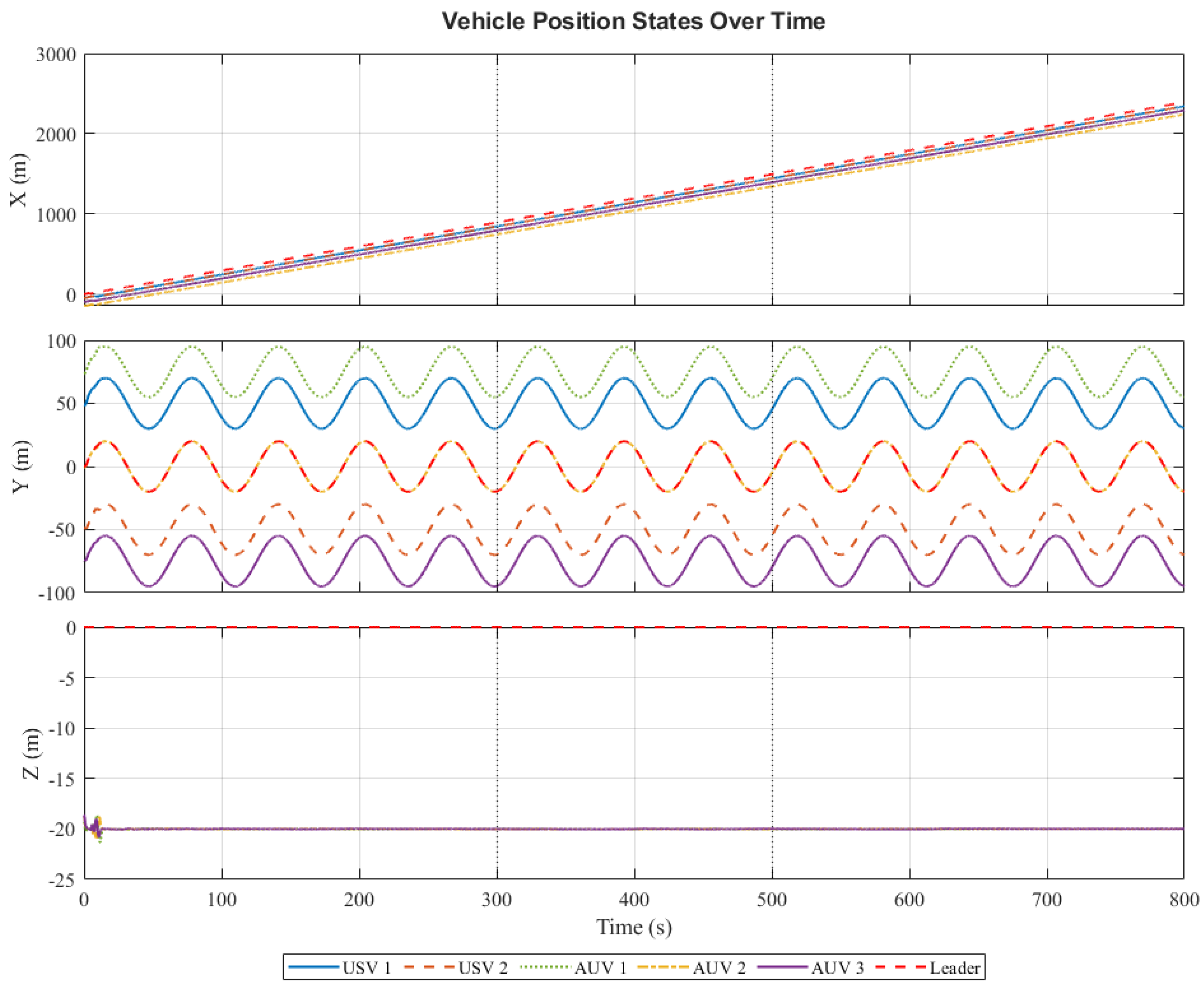

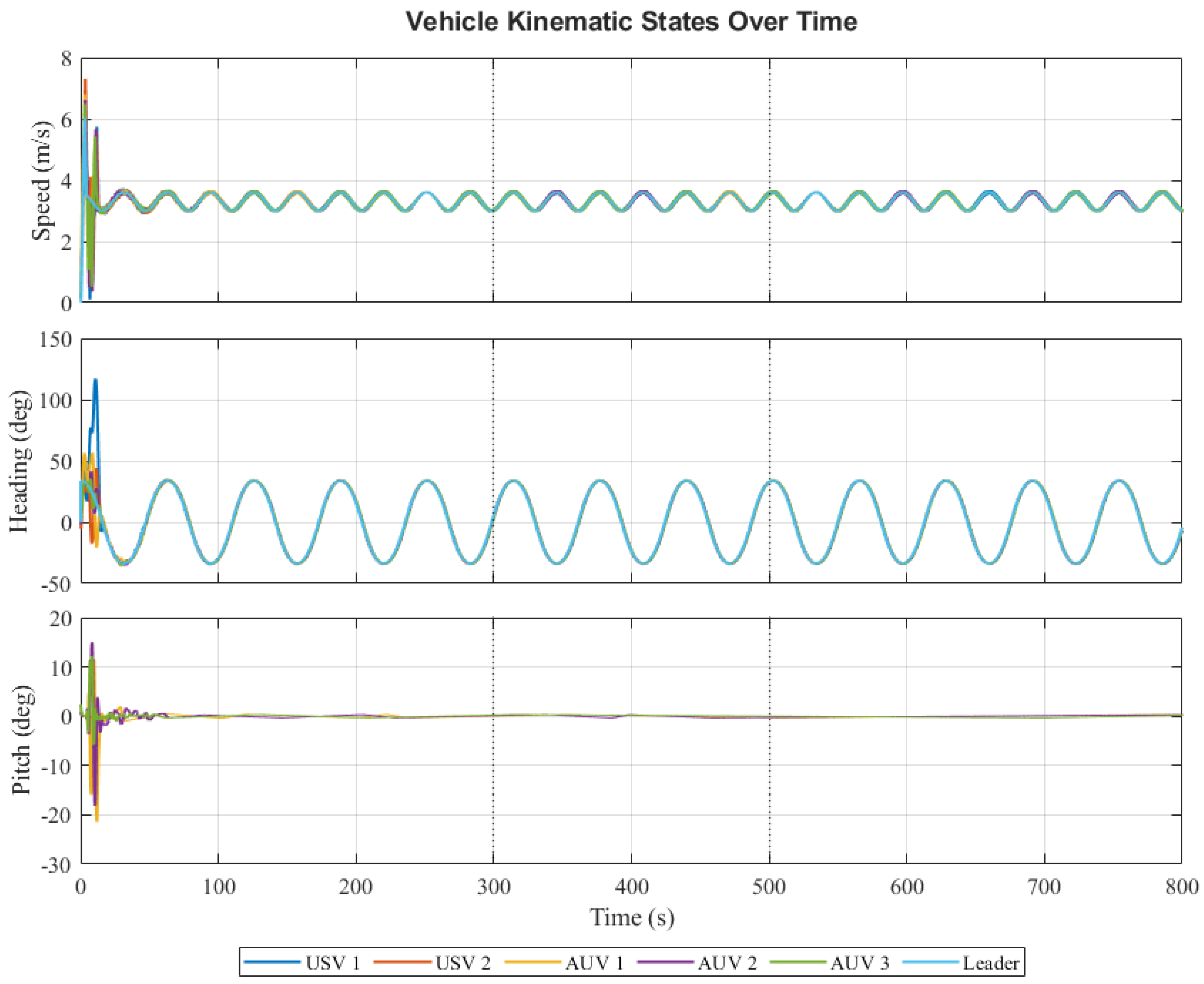

- Platform Composition: The formation consists of one leader USV (), two follower USVs (), and three follower AUVs (). The USVs use a 3-degree-of-freedom (surge, sway, yaw) dynamic model, while the AUVs use a 6-degree-of-freedom dynamic model. Their specific dynamic parameters, including mass, inertia matrix, and hydrodynamic coefficients, are set based on typical values from the reference [29].

- Environment Setting: The simulation is conducted in a three-dimensional marine space. To simulate a realistic environment, a constant ocean current with a velocity of along the positive X-axis is introduced as an external disturbance term for all platforms.

- Initial State: The initial positions and velocities of all follower platforms are randomly set near the leader’s initial position to simulate a non-ideal initial deployment state.

- (2)

- Formation Task Setting

- Leader’s Trajectory: The leader USV sails along a predefined sinusoidal trajectory. Its position in the inertial frame is given by the following equation:This trajectory simulates a common reciprocating survey path.

- Desired Formation: All followers are required to maintain a fixed pentagonal formation relative to the leader. The desired relative position vectors for each follower are set as follows:This formation requires the USVs to accompany on the surface, while the AUVs maintain a wider formation at a depth of 20 m, simulating a typical cross-domain collaborative operation scenario.

- (3)

- Communication and Fault SettingsThe basic communication topology of the formation is fully connected. At each time step, each communication link has a probability of remaining connected and a probability of disconnecting, thereby simulating a dynamically changing communication topology. All topologies are assumed to satisfy Assumption 1.

- (a)

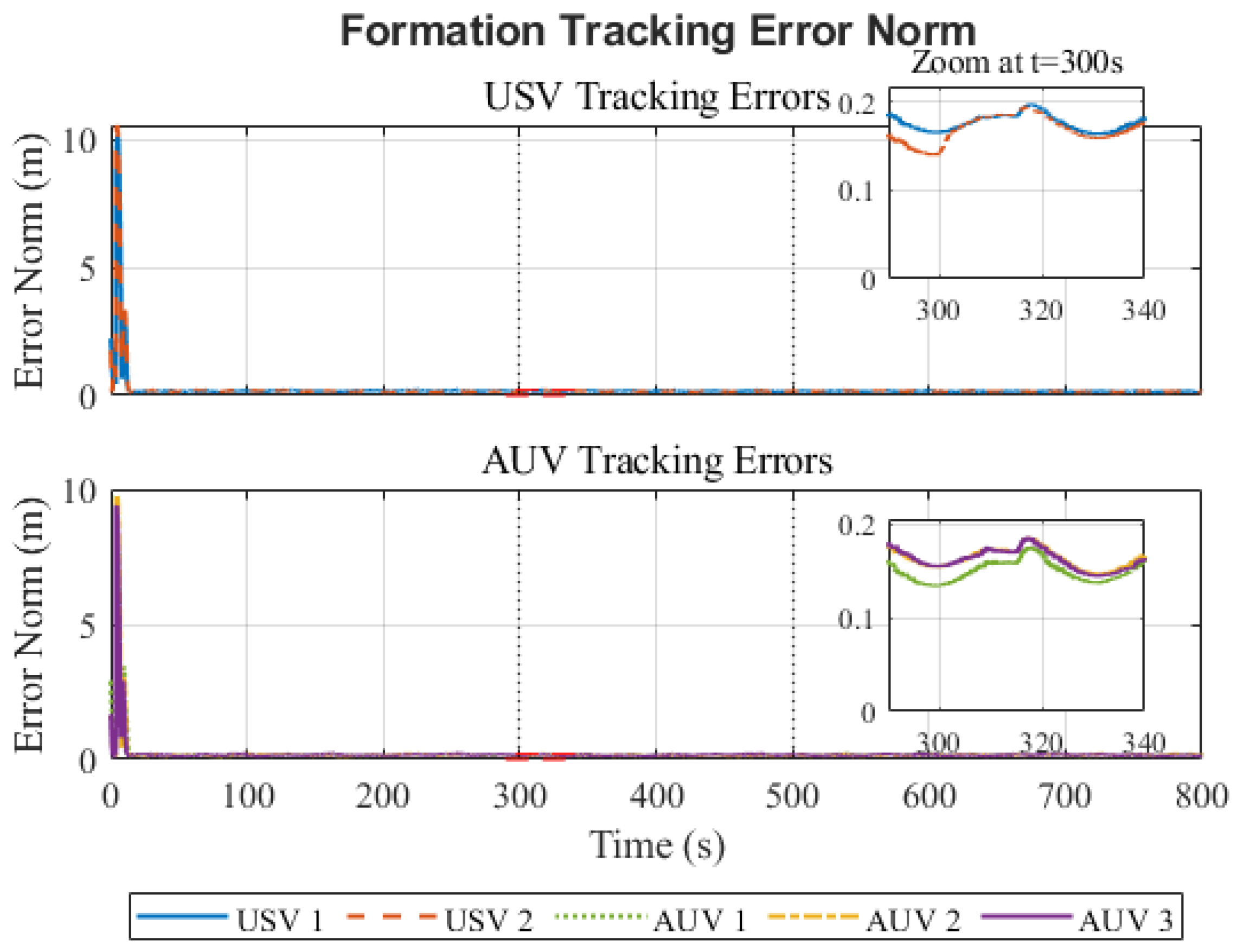

- Effectiveness Fault: At s, a 25% loss of effectiveness, a fault is injected into the main thruster of USV , meaning its effectiveness factor abruptly changes from 1 to 0.75.

- (b)

- Bias Fault: At s, a persistent bias fault of magnitude is injected into the vertical rudder of AUV .

- (4)

- Controller Parameter Settings

- (a)

- Sliding mode surface parameters: for all .

- (b)

- Sliding mode control gains: , .

- (c)

- Adaptive law gains: , , .

- (d)

- Dynamic event-triggering parameters: , , .

- (e)

- Boundary layer thickness: .

- (f)

- RBF Neural Network: Each follower’s controller uses an RBFNN to approximate the unknown nonlinear terms. Each RBFNN contains 20 neurons, with their centers uniformly distributed within the expected range of the input variables, and the width is uniformly set to 2, as shown in Figure 3.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Formation Tracking Performance

4.2.2. Communication Efficiency Analysis

4.2.3. Adaptive and Fault-Tolerant Capability Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, W.; Shan, Q.; Zhang, W. Cooperative path following control of USV-UAVs considering low design complexity and command transmission requirements. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, J.; Cui, Y.; Fu, D.; Cong, J. Multi-USV task planning method based on improved deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 18549–18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yang, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, H. Hybrid path planning method for USV using bidirectional A* and improved DWA considering the manoeuvrability and COLREGs. Ocean Eng. 2024, 298, 117210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, S. Robust practical prescribed time trajectory tracking of USV with guaranteed performance. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, D.; Pang, W.; Zhang, Y. A survey of underwater search for multi-target using Multi-AUV: Task allocation, path planning, and formation control. Ocean Eng. 2023, 278, 114393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.P.; Yao, Y. An adaptive distributed auction algorithm and its application to multi-AUV task assignment. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2023, 66, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Sha, Q. Hybrid form of differential evolutionary and gray wolf algorithm for multi-auv task allocation in target search. Electronics 2023, 12, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Cai, W. Hunting task allocation for heterogeneous multi-AUV formation target hunting in IoUT: A game theoretic approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 9142–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Lei, J.; Zhao, W. Improved analytical solution with optimization constraints using TDOA and FDOA measurements for USV/AUV collaborative localization. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 109760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, G.; Hou, X.; Men, W.; Ren, Y. Fisher-information-matrix-based usbl cooperative location in usv–auv networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Wu, D.; You, Z.; Wu, D.; Tu, W. Predefined-time terminal sliding mode cooperative trajectory tracking control for USV-AUV under weak communication. Ocean Eng. 2025, 333, 121459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Yao, Q.; Lu, X. Distributed fixed-time sliding mode formation control for unmanned aerial-ground vehicle (UAV-UGV) heterogeneous system. Asian J. Control 2025, 27, 1802–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, G.; Yuan, P.; Bai, J. Formation control of UAV–USV based on distributed event-triggered adaptive MPC with virtual trajectory restriction. Ocean Eng. 2024, 294, 116850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.F.; Rastgaar, M.; Mahmoudian, N. Heterogeneous Multi-Robot (UAV-USV-AUV) Collaborative Exploration with Energy Replenishment. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, T. IROA-based LDPC-Lévy method for target search of multi AUV–USV system in unknown 3D environment. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Lu, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, W. Distributed dynamic rendezvous control of the AUV-USV joint system with practical disturbance compensations using model predictive control. Ocean Eng. 2022, 258, 111268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, M.; Tan, X. Disturbance observer-based event-triggered control of switched positive systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Exp. Briefs 2023, 71, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Sun, Z.; Wen, G.; Duan, Z. Data-driven dynamic event-triggered control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 8804–8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chadli, M. Observer-based distributed dynamic event-triggered control of multi-agent systems with adjustable interevent time. Asian J. Control 2024, 26, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewlia, M.; Zelazo, D. Bearing-based formation stabilization using event-triggered control. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2024, 34, 4375–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Wen, C.; Qin, S. Adaptive generalized nash equilibrium seeking algorithm for nonsmooth aggregative game under dynamic event-triggered mechanism. Automatica 2024, 169, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; He, W.; Du, W.; Tian, Y.-C.; Han, Q.-L.; Qian, F. Distributed gradient tracking for differentially private multi-agent optimization with a dynamic event-triggered mechanism. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 3044–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Duan, Z.; Wen, G.; Sun, Z. A novel dynamic event-triggered mechanism for dynamic average consensus. Automatica 2024, 161, 111495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; He, W.; Xu, W. Dynamic event-triggered mechanism for distributed Nash equilibrium seeking under switching topologies. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, P.; Feng, X. Distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control for high-speed trains using multi-agent system model. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.T.; Zhu, S.L.; Wang, D.M.; Han, Y.Q. Distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control with prescribed performance for nonlinear multiagent systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2024, 138, 108222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Sun, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Su, C.-Y. Hierarchical distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control of nonlinear fractional-order multiagent systems with faults and periodic disturbances using event-triggered communication. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 5231–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Yang, G.H. Distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control approach to cooperative output regulation for linear multi-agent systems. Automatica 2019, 103, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, T.; Fossen, T.I. Kinematic models for manoeuvring and seakeeping of marine vessels. Model. Identif. Control 2007, 28, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|

| Set of all platforms (0 = leader, = followers) | |

| Set of directed communication edges at time t | |

| Adjacency, Navigation, and Laplacian matrices | |

| Composite matrix | |

| Position/attitude vector and linear/angular velocity vector (of agent i) | |

| Inertia, Coriolis, and Damping matrices | |

| Commanded and Actual (post-fault) control input | |

| Actuator effectiveness matrix and bias fault vector | |

| Estimated effectiveness factor matrix and estimated RBFNN weights | |

| Communication delay from platform j to i | |

| Position and velocity formation tracking errors | |

| Sampled state measurement error (due to DETM) | |

| Dynamic event-triggering threshold | |

| Sliding mode surface variable | |

| Ideal and basis function vector of RBFNN |

| Metric | USV 1 | USV 2 | AUV 1 | AUV 2 | AUV 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (m) | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| MAE (m) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Total Triggers (800 s) | 28 | 33 | 30 | 34 | 29 |

| Avg. Trigger Interval (s) | 28.5 | 24.2 | 26.7 | 23.5 | 27.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, X. Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Heterogeneous USV-AUV Swarms Based on Dynamic Event Triggering. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112116

Wang H, Wang H, Guo X. Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Heterogeneous USV-AUV Swarms Based on Dynamic Event Triggering. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112116

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haitao, Hanyi Wang, and Xuan Guo. 2025. "Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Heterogeneous USV-AUV Swarms Based on Dynamic Event Triggering" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112116

APA StyleWang, H., Wang, H., & Guo, X. (2025). Distributed Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Heterogeneous USV-AUV Swarms Based on Dynamic Event Triggering. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112116