Distinct Pathways of Cadmium Immobilization as Affected by Wheat Straw- and Soybean Meal-Mediated Reductive Soil Disinfestation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil and Substance Preparations

2.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

2.3. Determination of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

2.4. DNA Extraction and Amplicon Sequencing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

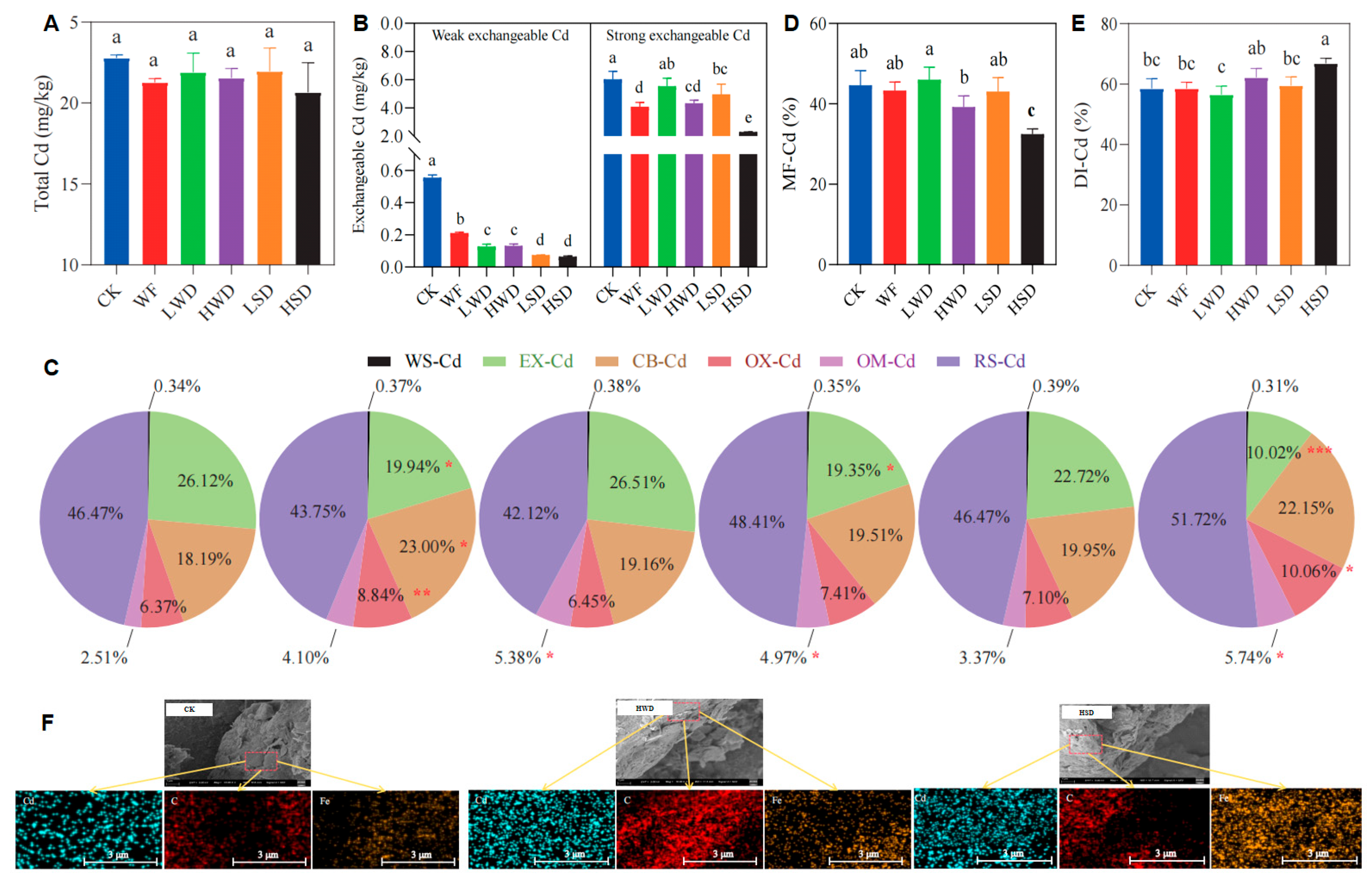

3.1. Changes in Soil Cd Extractability and Fractions

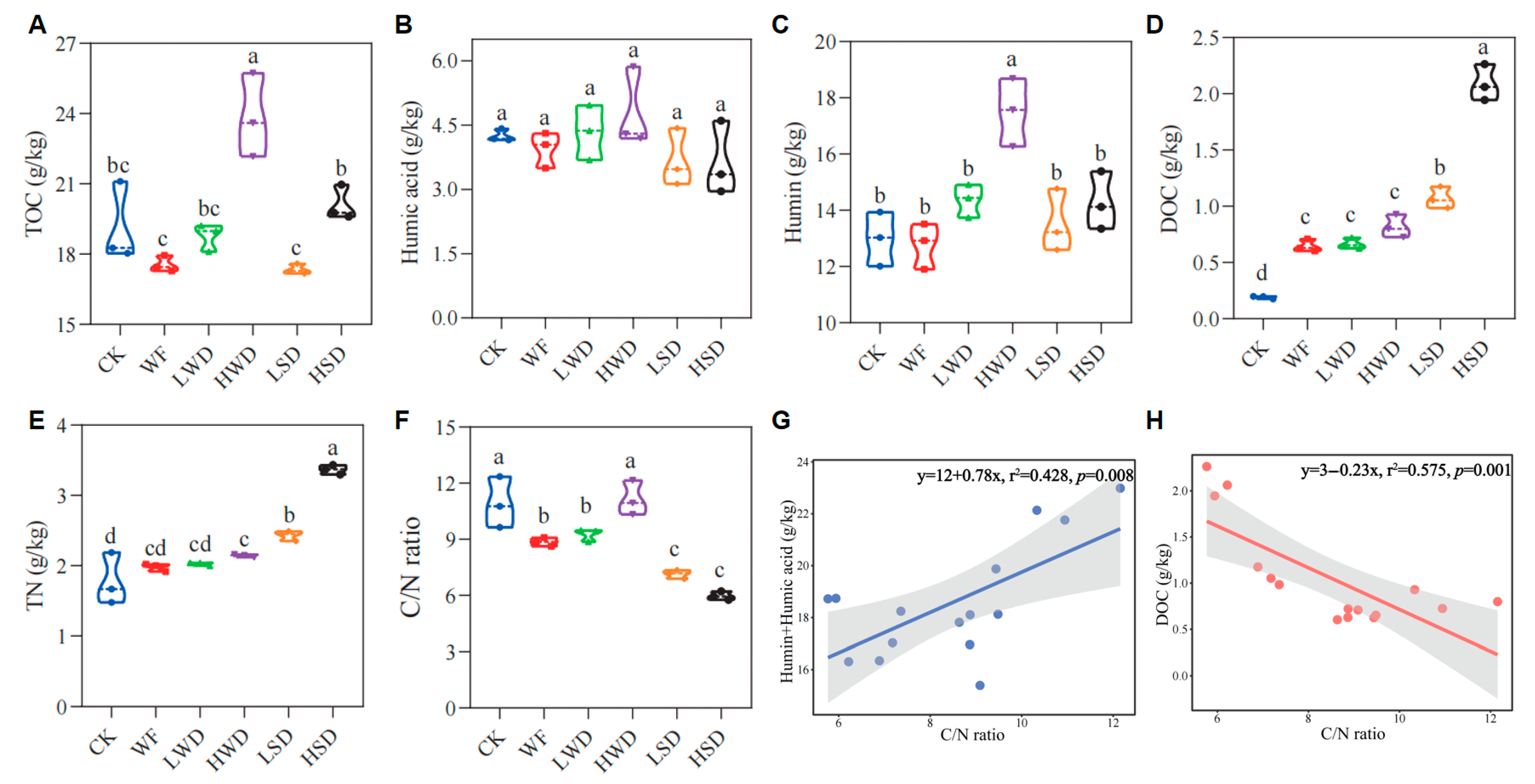

3.2. Changes in Soil Total Organic Carbon and Its Fractions

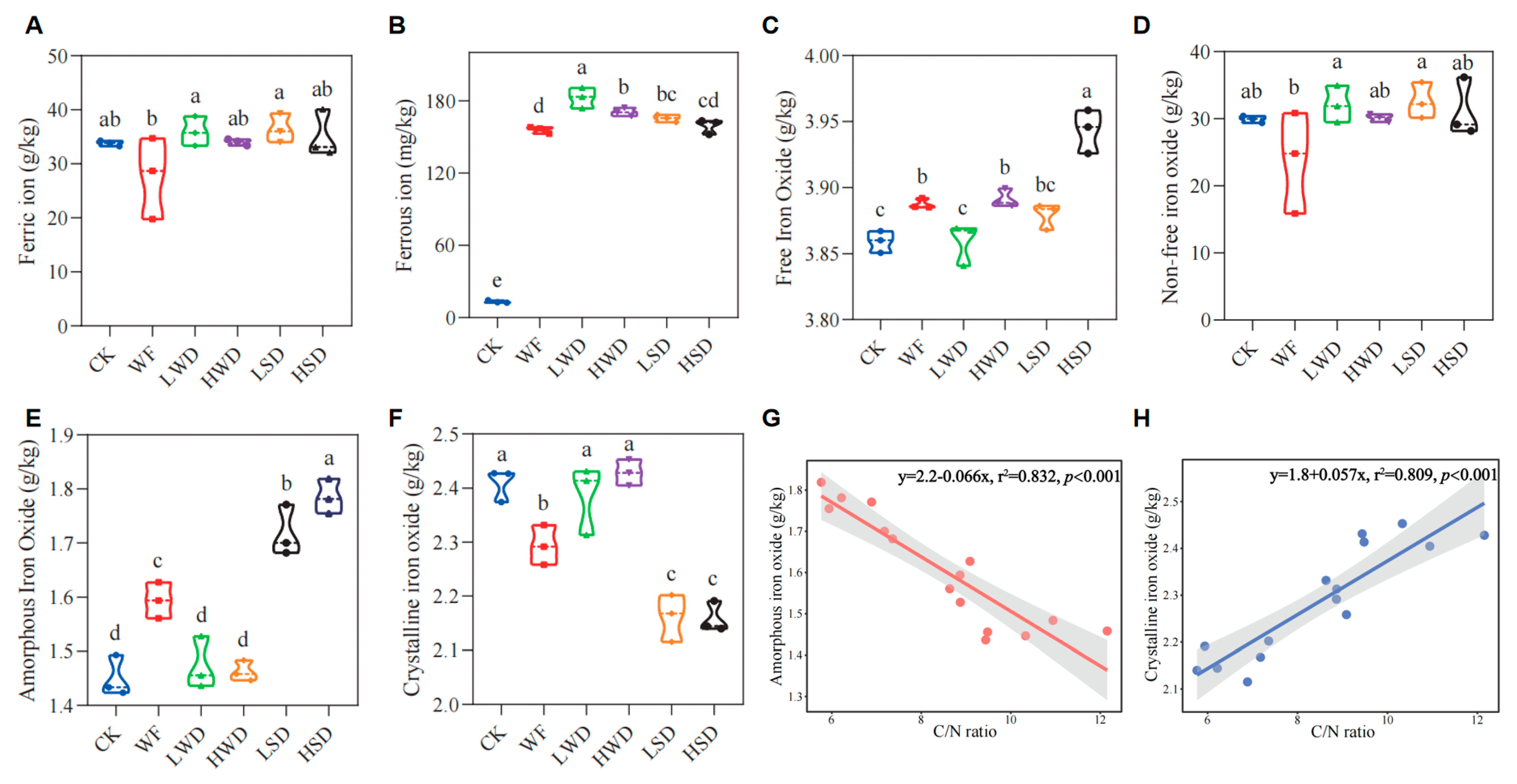

3.3. Changes in Soil Iron Valence and Iron Oxide Fractions

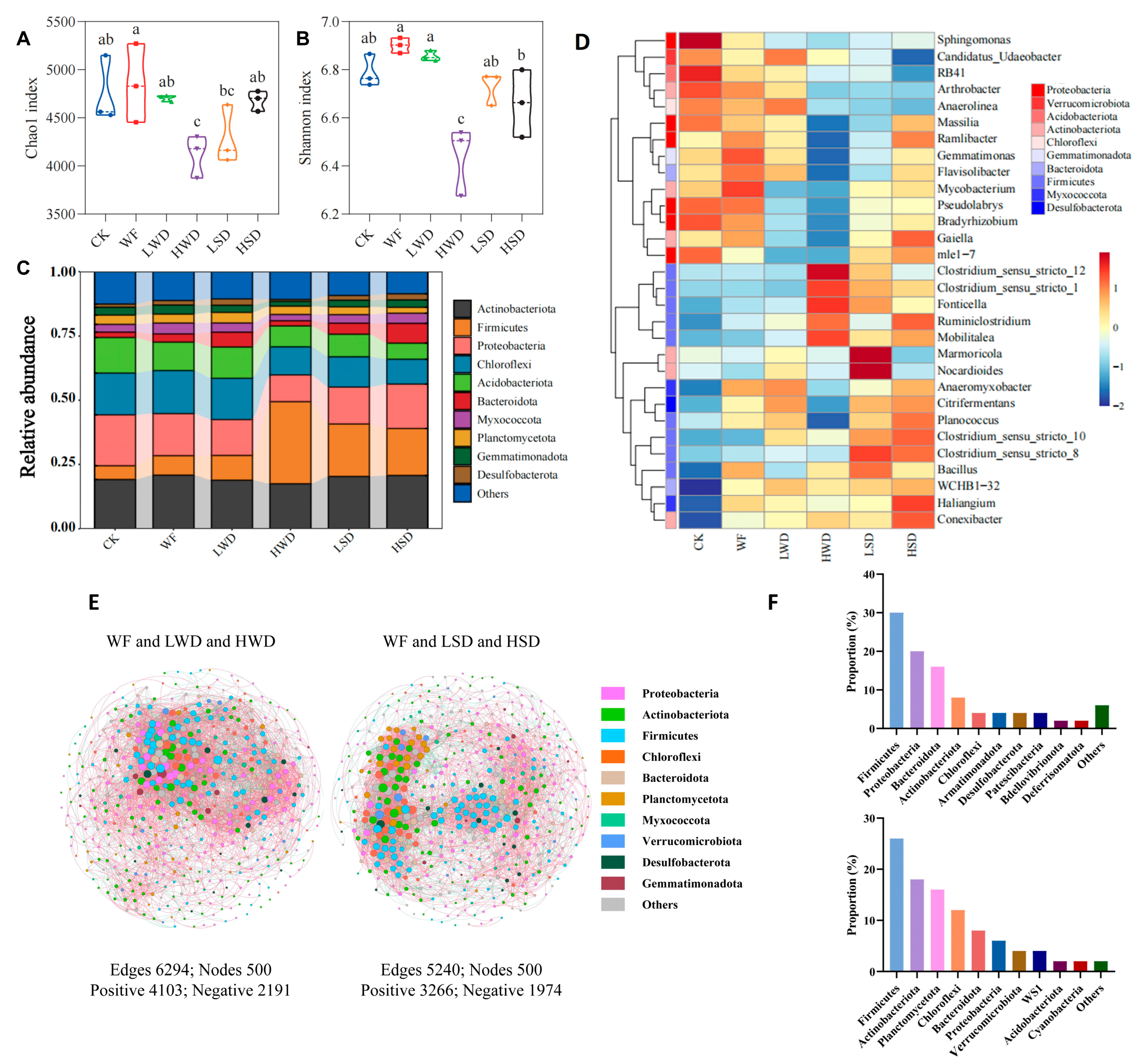

3.4. Changes in Soil Bacterial Microbial Community and Network Connections

3.5. Changes in Soil Bacterial Life Strategies, Iron-Reducing Bacteria, and Function Prediction

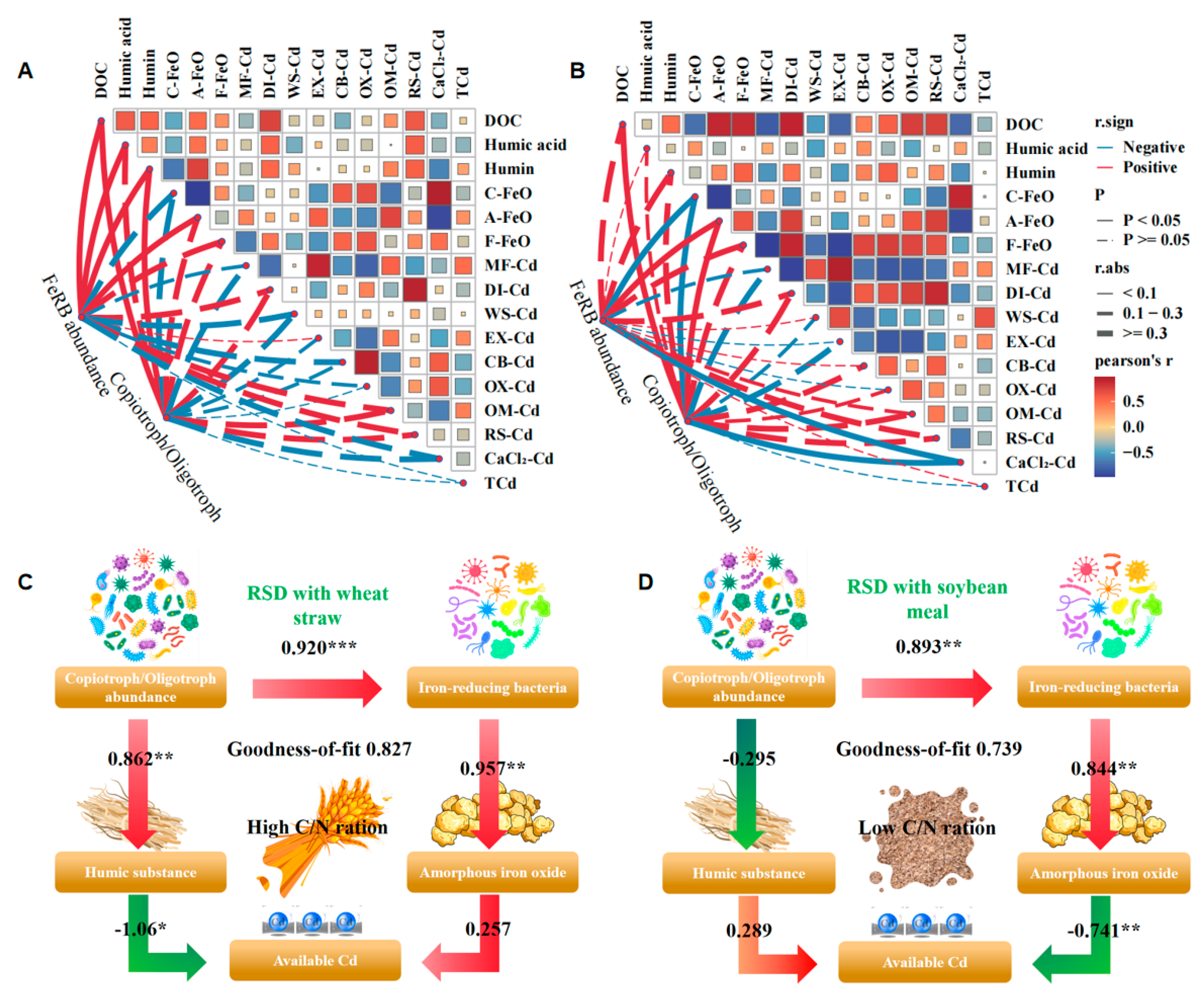

3.6. Relationship Among Soil Chemical Properties, Bacterial Microbial Communities, and Cd Fractions

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Cd Bioavailability and Fractions Affected by RSD with Distinct Organic Sources

4.2. Soil Organic Carbon Transformation and Its Linkage to Cd Bioavailability Affected by RSD with Distinct Organic Sources

4.3. Soil Iron Oxide Transformation and Its Linkage to Cd Bioavailability Affected by RSD with Distinct Organic Sources

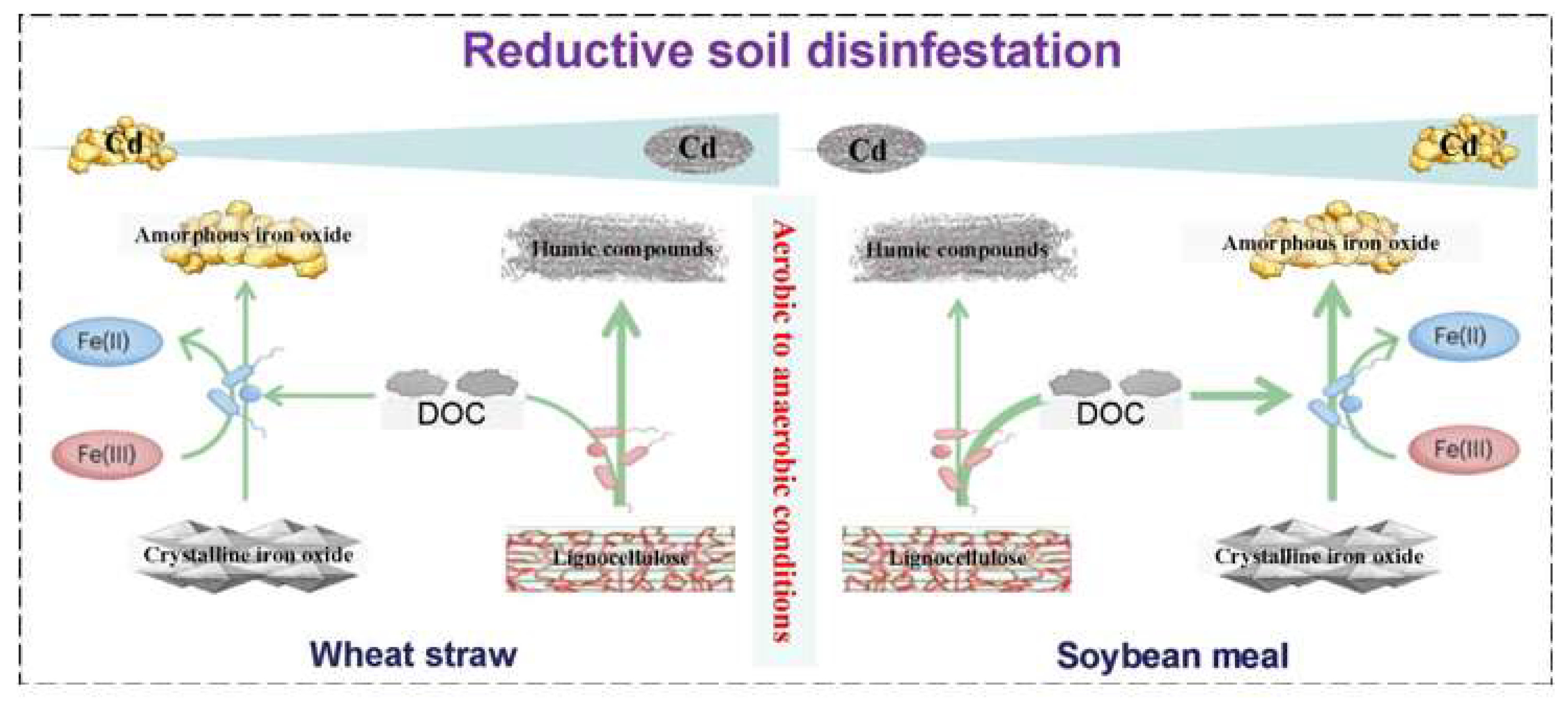

4.4. Driving Role and Conceptual Mechanism of Bacterial Life Strategies and Iron-Reducing Bacteria in Soil Cd Immobilization Under Different Organic Source RSD Treatments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RSD | Reductive soil disinfestation |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| MF–Cd | Mobility factor of Cd |

| DI–Cd | Distribution index of Cd |

| WS–Cd | Water soluble bound Cd fraction |

| EX–Cd | Exchangeable Cd fraction |

| CB–Cd | Carbonate-bound Cd fraction |

| OX–Cd | Iron oxide-bound Cd fraction |

| OM–Cd | Organic-bound Cd fraction |

| RS–Cd | Residual bound Cd fraction |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| TFe | Total iron |

| Fr–FeO | Free iron oxide |

| A–FeO | Amorphous iron oxide |

| C–FeO | Crystalline iron oxide |

| FeRB | Iron-reducing bacteria |

References

- Hu, X.; Li, X.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, S.; Su, K.W.; Qiu, Z.L.; Li, X.H.; Zhao, Q.C.; Yu, C.H. Study on the spatial distribution of ureolytic microorganisms in farmland soil around tailings with different heavy metal pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 144946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.Y.; Jia, X.Y.; Wang, L.W.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Yuan, Z.M.; Wang, T.Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, F. Bioremediation of Cd by strain GZ-22 isolated from mine soil based on biosorption and microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, C.; Xu, R.S.; Pei, Z.R.; Li, F.C.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, F.; Liang, Y.R.; Li, Z.H.; et al. Linking soil organic carbon dynamics to microbial community and enzyme activities in degraded soil remediation by reductive soil disinfestation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 189, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, A.; Kaku, N.; Ueki, K. Role of anaerobic bacteria in biological soil disinfestation for elimination of soil-borne plant pathogens in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6309–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; Yang, K.J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Mi, H.Z.; Li, C.; Li, Z.H.; Pei, Z.R.; Chen, F.; Yan, J.T.; et al. Reductive soil disinfestation attenuates antibiotic resistance genes in greenhouse vegetable soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.H.; Xu, R.S.; Song, J.X.; Chen, A.L.; Chen, F.; Liang, Y.R.; Guo, D.; Tang, X.; Qin, Z.M.; et al. Short-term responses of soil organic carbon and chemical composition of particle-associated organic carbon to anaerobic soil disinfestation in degraded greenhouse soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 4428–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Dai, X.Z.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Tao, Y.; Chen, W.C.; Zhang, M.X.; et al. Improved immobilization of soil cadmium by regulating soil characteristics and microbial community through reductive soil disinfestation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 153862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tao, Y.; Chen, F.; Tan, F.J.; Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Xue, T.; Xie, Y.H. The responses of soil Cd fractions to disinfestation regimes associated with microbial communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 193, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.Q.; Xi, J.; Ke, J.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Chen, X.T.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Lin, Y. Deciphering soil amendments and actinomycetes for remediation of cadmium (Cd) contaminated farmland. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 249, 114388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Mi, B.; Luo, C.; Zhao, W.J.; Zhu, Y.L.; Chen, L.; Tu, N.M.; Wu, F.F. Mechanisms insights into Cd passivation in soil by lignin biochar: Transition from flooding to natural air-drying. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 472, 134565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, V.; De Martino, A.; Nebbioso, A.; Di Meo, V.; Salluzzo, A.; Piccolo, A. Plant tolerance to mercury in a contaminated soil is enhanced by the combined effects of humic matter addition and inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 11312–11322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Pi, B.Y.; Dai, J.T.; Nie, Z.; Yu, G.R.; Du, W.P. Effects of humic acid on the growth and cadmium accumulation of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2025, 27, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.K.; Wang, K.; Liang, T.; Wang, T.S.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.F.; Xu, C.X.; Cao, W.D.; Fan, H.L. Milk vetch returning combined with lime materials alleviates soil cadmium contamination and improves rice quality in soil-rice system. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, R.; Si, T.R.; Lu, Q.Q.; Bian, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Zheng, J.F.; Cheng, K.; Joseph, S.; et al. Rape straw biochar enhanced Cd immobilization in flooded paddy soil by promoting Fe and sulfur transformation. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.D.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Tang, S.; Cheng, W.L.; Li, M.; Bu, R.Y.; Han, S.; Geng, M.J. Combined application of chemical fertilizer with green manure increased the stabilization of organic carbon in the organo-mineral complexes of paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2023, 30, 2676–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, T.R.; Chen, X.; Yuan, R.; Pan, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Bian, R.J.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Joseph, S.; Li, L.Q.; et al. Iron-modified biochars and their aging reduce soil cadmium mobility and inhibit rice cadmium uptake by promoting soil iron redox cycling. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.P.; Bolan, N.S.; Lai, J.H.; Wang, Y.S.; Jin, X.H.; Kirkham, M.B.; Wu, X.L.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.L. Interactions between organic matter and Fe (hydr)oxides and their influences on immobilization and remobilization of metal(loid)s: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 52, 4016–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desie, E.; Vancampenhout, K.; Nyssen, B.; van den Berg, L.; Weijters, M.; van Duinen, G.J.; den Ouden, J.; Van Meerbeek, K.; Muys, B. Litter quality and the law of the most limiting: Opportunities for restoring nutrient cycles in acidified forest soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.L.; Shi, J.H.; Liu, Z.W.; Kan, Y.D.; Bao, W.K. Application of crop straw with different C/N ratio affects CH4 emission and Cd accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Cd polluted paddy soils. Clim. Smart Agric. 2004, 2, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Sun, G.X.; Chen, S.C.; Fang, Z.; Yuan, H.Y.; Shi, Q.; Zhu, Y.G. Molecular chemodiversity of dissolved organic matter in paddy soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.B.; Liu, X.P.; Shu, Y.C.; Li, G.; Sun, C.L.; Jones, D.L.; Zhu, Y.G.; Lin, X.Y. Molecular composition of exogenous dissolved organic matter regulates dissimilatory iron reduction and carbon emissions in paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 12679–12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldford, J.E.; Lu, N.X.; Bajić, D.; Estrela, S.; Tikhonov, M.; Sanchez-Gorostiaga, A.; Segrè, D.; Mehta, P.; Sanchez, A. Emergent simplicity in microbial community assembly. Science 2018, 361, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.Y.; Liu, S.B.; Liu, X.M.; Tan, X.F.; Guo, S.; Dai, M.Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, G.B.; Feng, C.Z. Doped carbon dots affect heavy metal speciation in mining soil: Changes of dissimilated iron reduction processes and microbial communities. Environ. Sci.-Nano 2024, 11, 1724–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, Y.; Song, J.X.; Liang, Y.R.; Chen, F.; Wei, X.M.; Li, C.; Liu, W.B.; Rensing, C.; et al. Linking bacterial life strategies with the distribution pattern of antibiotic resistance genes in soil aggregates after straw addition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S.; Zhang, H.Y.; Razavi, B.; Chang, F.D.; Yu, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Kuzyakov, Y. Bacterial necromass as the main source of organic matter in saline soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smebye, A.; Alling, V.; Vogt, R.D.; Gadmar, T.C.; Mulder, J.; Cornelissen, G.; Hale, S.E. Biochar amendment to soil changes dissolved organic matter content and composition. Chemosphere 2016, 142, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.H.; Liu, J.; Shu, Z.P.; Chen, Y.L.; Pan, Z.Z.; Peng, C.; Wang, X.X.; Zhou, F.W.; Zhou, M.; Du, Z.L.; et al. Microbially driven iron cycling facilitates organic carbon accrual in decadal biochar-amended soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 12430–12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappler, A.; Bryce, C.; Mansor, M.; Lueder, U.; Byrne, J.M.; Swanner, E.D. An evolving view on biogeochemical cycling of iron. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.H.; Li, L.; Liu, X.W.; Zhao, Z.Q. Rape straw application facilitates Se and Cd mobilization in Cd-contaminated seleniferous soils by enhancing microbial iron reduction. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.M.; Weller, D.L.; Reiter, M.S.; Bardsley, C.A.; Eifert, J.; Ponder, M.; Rideout, S.L.; Strawn, L.K. Anaerobic soil disinfestation, amendment-type, and irrigation regimen influence Salmonella survival and die-off in agricultural soils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 2342–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.R.; Gong, C.P.; Gao, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.S.; Zhou, L.Y.; Lou, Q.; Zhao, Y.F.; Zhuang, H.F.; Zhang, J.; Shan, S.D.; et al. Reducing antibiotic resistance genes in soil: The role of organic materials in reductive soil disinfestation. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 74, 126245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, Z.L.; Cai, T.G.; Zhu, D.; Chen, C.; Duan, G.L. Effects of reductive soil disinfestation on potential pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes in soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 150, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.Y.; Liao, H.K.; Shu, L.Z.; Yao, H.Y. Effect of Different Substrates on Soil Microbial Community Structure and the Mechanisms of Reductive Soil Disinfestation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Ge, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wu, L.H.; Christie, P. Phytoextraction of highly cadmium-polluted agricultural soil by Sedum plumbizincicola: An eight-hectare field study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.G.; Yang, Y.; Yang, W.J.; Li, M.M.; Zheng, F.Y.; Zeng, X.Y.; Deng, X.; Zou, D.S.; Zeng, Q.R. Synergistic effects of rhizosphere microbial communities and low molecular weight organic acids on Cd accumulation in Helianthus annuus L. in low-to-moderate cadmium-contaminated farmland. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Compbell, P.G.C.; Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. J. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000.

- GSB 04-1767-2004; 24-Element Mixed Standard Solution for ICP. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Husson, O.; Brunet, A.; Babre, D.; Hubert Charpentier, H.; Durand, M.; Sarthou, J.P. Conservation agriculture systems alter the electrical characteristics (Eh, pH and EC) of four soil types in France. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 176, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Shi, J.L.; Tian, X.H.; Jia, Z.; Wang, S.X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, W.L. Impact of dissolved organic matter on Zn extractability and transfer in calcareous soil with maize straw amendment. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 19, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Yang, Z.X.; Li, W.Q.; Zhao, Y.D.; Xia, J.; Dong, W.Y.; Chen, B.Q. Effects of different straw return modes on soil carbon, nitrogen, and greenhouse gas emissions in the semiarid maize field. Plants 2024, 13, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakina, L.G.; Drichko, V.F.; Orlova, N.E. Regularities of extracting humic acids from soils using sodium pyrophosphate solutions. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2017, 50, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.X.; Huang, X.L.; Li, L.N.; Li, T.L.; Duan, Y.H.; Ling, N.; Yu, G.H. Rejuvenation of iron oxides enhances carbon sequestration by the ‘iron gate’ and ‘enzyme latch’ mechanisms in a rice-wheat cropping system. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 156209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Hu, P.L.; Xiao, D.; Wang, Z.C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.L. Lower sensitivity of soil carbon and nitrogen to regional temperature change in karst forests than in non-karst forests. Forests 2023, 14, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Fu, Q.L.; Wu, T.L.; Cui, P.X.; Fang, G.D.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.M.; Liu, G.X.; Wang, W.C.; Wang, D.X.; et al. Active iron phases regulate the abiotic transformation of organic carbon during redox fluctuation cycles of paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 14281–14293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, L.; Custer, G.F.; Koslicki, D.; Dini-Andreote, F. Interplay of ecological processes modulates microbial community reassembly following coalescence. ISME 2025, 19, wraf041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 385–688.672295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Liu, Y.W.; Liu, G.L.; Guo, Y.Y.; Yang, Q.Q.; Shi, J.B.; Hu, L.G.; Liang, Y.; Yin, Y.G.; Cai, Y.; et al. Aging and phytoavailability of newly introduced and legacy cadmium in paddy soil and their bioaccessibility in rice grain distinguished by enriched isotope tracing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.Y.; Nie, X.X.; Liu, B.; Li, F.M.; Yang, L. Efficiency of in-situ passivation remediation in cadmium-contaminated farmland soil and its mechanism: A review. J. Agric. Res. Environ. 2021, 38, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.N.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.F. Regulating facility soil microbial community and reducing cadmium enrichment in lettuce by reductive soil disinfestation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1465882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A.; Prasad, M.N.V. Cadmium minimization in rice. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, L.H.; Luo, Y.M.; Christie, P. Effects of organic matter fraction and compositional changes on distribution of cadmium and zinc in long-term polluted paddy soils. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, A.Q.; Fan, J.Z.; Lan, T.; Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C. Distinct impacts of reductive soil disinfestation and chemical soil disinfestation on soil fungal communities and memberships. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7623–7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J.H.; Fu, X.H.; Le, Y.Q. The variability and causes of organic carbon retention ability of different agricultural straw types returned to soil. Environ. Technol. 2017, 38, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; Nie, M.; Hou, D.Y.; Liu, H.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Ni, H.W.; Huang, W.G.; Zhou, J.Z.; et al. Relative increases in CH4 and CO2 emissions from wetlands under global warming dependent on soil carbon substrates. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Mason-Jones, K.; Wei, L.; Chen, X.B.; Wu, J.S.; Ge, T.D.; Zhu, Z.K. Stability of iron-carbon complexes determines carbon sequestration efficiency in iron-rich soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 203, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chang, J.J.; Li, L.F.; Lin, X.Y.; Li, Y.C. Soil amendments alter cadmium distribution and bacterial community structure in paddy soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Tan, X.Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.Y.; Xiang, C.; Wu, C.; Guo, J.K.; Xue, S.G. Simultaneous stabilization of cadmium and arsenic in soil by humic acid and mechanically activated phosphate rock. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovley, D.R.; Blunt-Harris, E.L. Role of humic-bound iron as an electron transfer agent in dissimilatory Fe(III) reduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4252–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.R. Microbial reduction of metals and radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Dong, H.L.; Reguera, G.; Beyenal, H.; Lu, A.H.; Liu, J.; Yu, H.Q.; Fredrickson, J.K. Extracellular electron transfer mechanisms between microorganisms and minerals. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.C.; Ma, M.K.; Chen, W.L.; Cai, P.; Yu, X.Y.; Feng, X.H.; Huang, Q.Y. Modeling of Cd adsorption to goethite-bacteria composites. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.X.; Shi, Z.; He, H.Y.; Lin, B.J.; He, C.; Dang, Y.P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Improving soil organic carbon sequestration through conservation tillage incorporating legume-based crop rotations. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 255, 106792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Ma, Q.; Marsden, K.A.; Chadwick, D.R.; Luo, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wu, L.H.; Jones, D.L. Microbial community succession in soil is mainly driven by carbon and nitrogen contents rather than phosphorus and sulphur contents. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 180, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oña, L.; Kost, C. Cooperation increases robustness to ecological disturbance in microbial cross-feeding networks. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.W.; Ma, X.Z.; Chu, S.H.; You, Y.M.; Chen, X.F.; Wang, J.C.; Wang, R.Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, T.; et al. Nitrogen cycle induced by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria drives “microbial partners” to enhance cadmium phytoremediation. Microbiome 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, T.; Mei, J.; Li, C.; Hou, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, R.; Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Song, J.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Distinct Pathways of Cadmium Immobilization as Affected by Wheat Straw- and Soybean Meal-Mediated Reductive Soil Disinfestation. Agriculture 2026, 16, 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020242

Xu T, Mei J, Li C, Hou L, Wang K, Xu R, Wei X, Zhang J, Song J, Yuan Z, et al. Distinct Pathways of Cadmium Immobilization as Affected by Wheat Straw- and Soybean Meal-Mediated Reductive Soil Disinfestation. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):242. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020242

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Tengqi, Jingyi Mei, Cui Li, Lijun Hou, Kun Wang, Risheng Xu, Xiaomeng Wei, Jingwei Zhang, Jianxiao Song, Zuoqiang Yuan, and et al. 2026. "Distinct Pathways of Cadmium Immobilization as Affected by Wheat Straw- and Soybean Meal-Mediated Reductive Soil Disinfestation" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020242

APA StyleXu, T., Mei, J., Li, C., Hou, L., Wang, K., Xu, R., Wei, X., Zhang, J., Song, J., Yuan, Z., Tian, X., & Chen, Y. (2026). Distinct Pathways of Cadmium Immobilization as Affected by Wheat Straw- and Soybean Meal-Mediated Reductive Soil Disinfestation. Agriculture, 16(2), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020242