1. Introduction

Understanding the airflow patterns inside livestock buildings is one of the key issues to evaluate animals and farm workers health, as well as environmental impact. With the air, excess heat and humidity, as well as pollutants like ammonia, odors, and dust, are carried away [

1]. Adequate air exchange ensures a comfortable indoor climate (temperature, humidity, gas concentrations) and helps to control emissions to the environment. Hence, a detailed understanding of air motion (i.e., air velocities, flow directions, and turbulence) is necessary to meet livestock needs and environmental regulations [

2]. In naturally ventilated livestock buildings, however, airflow is complex and highly variable as it is driven by the interaction of wind and thermal forces. Moving livestock, itself acting as flow obstacle, renders the situation even more complex [

3,

4]. Simulating animals in realistic or simplified geometries using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is computationally challenging for real-time or quasi-real-time applications, especially for large-sized commercial livestock houses (often more than one thousand square meters of floor space) housing large numbers of animals inside (often several hundreds or thousands of animals) or for the parametric studies with numerous simulation cases. As a result, porous media modeling of animals has emerged as a feasible alternative.

Obtaining high-resolution airflow data through direct measurements and predicting airflow patterns in real livestock houses is very challenging. In the case of naturally ventilated buildings, hundreds of square meters of “window” area and fluctuating boundary conditions (e.g., highly variable wind velocity) render it particularly challenging to capture representative flow rates, leading to errors of up to 100% in some cases [

1]. Purely experimental approaches need long monitoring periods covering multiple seasons to capture a statistically significant dataset with measurements under comparable boundary conditions [

5]. At the same time, they usually struggle to provide the flow field information in sufficient resolution [

2]. As a result, field measurements of ventilation rates and interior airflow often suffer from low spatial resolution and high uncertainty.

Therefore, in recent decades, CFD has become a support tool to complement barn airflow measurements as it can resolve the interior airflows of livestock buildings with theoretically unlimited spatial resolution [

2,

6,

7]. By using CFD, researchers can virtually observe air speed and circulation in every corner of the building, under various ventilation scenarios, which is invaluable for diagnosing ventilation effectiveness and improving barn designs.

While CFD offers, in principle, high resolution, modeling a large barn in full geometric detail poses serious challenges. Ideally, the CFD model includes every interior object (animals, pens, equipment, etc.) explicitly in the geometry. However, meshing dozens of objects with realistic shapes would result in an extremely large number of computational cells. As a result, comprehensive CFD simulations with fully detailed animal geometry can suffer from convergence problems in the solver and often become too slow or even infeasible to run for many practical purposes [

7,

8].

The setup of comprehensive parameter studies or quasi-real-time simulations, thus, requires an efficient parametrization of areas that are characterized by complex geometries. One way to tackle this problem is by using a sub-grid-scale modeling approach for the animals and other interior obstacles. In this direction, even when using steady-state approaches such as Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS), it is common to parametrize small-scale flow obstacles as porous zones, for example, using the Darcy law [

9]. Porous media modeling has been used to model partitions or slatted floors or the animals themselves as flow obstacles within the animal occupied zones (AOZ) [

10,

11,

12]. In this approach, the cumulative effect of the interior or animals on the airflow (drag and turbulence) is represented by porous media parameters (such as pressure resistance coefficients). It has been found that, compared to 3D modeled geometries of 22 dairy cows, a porous media model can save around 90% computational time based on 15 CPUs for steady-state simulations while still capturing the bulk effect of the obstacles on airflow, representing a good compromise between accuracy and simulation efficiency [

13].

Despite the fact that the actual values of the resistance can depend considerably on the object distribution and the incident angle of the flow, many authors have considered the porous medium as isotropic in the three main directions [

12,

14]. Recent studies showed that this simplification of isotropic zones with a fixed resistance coefficient can lead to larger inaccuracy when calculating local air exchange of the AOZ under turbulent flow conditions [

13]. Implementing the direction-dependent coefficients improves the porous model’s predictions compared to a fully resolved geometry model [

7].

To build a reliable sub-grid (porous) model of a larger group of animals, it is crucial to understand how various configuration parameters of the animal group affect the overall pressure drop across the zone. Different configurations can include the number of animals (which determines the porosity or solid volume fraction of the zone), the spacing and arrangement of animals (which relates to the tortuosity of the porous zone and the airflow paths through it), and the orientation of animals relative to the wind (i.e., the individual blocking potential). Each of these factors can alter the pressure drop.

Bustos-Vanegas et al. [

3] simulated the airflow around lying and standing cows and showed that the viscous resistance was significant only in the case of a standing configuration or under cross-flow conditions. The largest influence of the wind angle was observed for the cows in standing position where inertial force decreased by about half when the direction changes from cross-flow to transvers flow. Further Hartje [

7] found for a single cow model that the pressure drop was highest when a cow was lying down broadside to the flow and lowest when the cow was standing facing the flow head-on. In general, a larger frontal area exposed to the airflow (such as a cow’s side profile vs. front profile) creates a greater resistance and pressure drop [

7]. In the case of pigs, for example, Wu et al. [

15] showed that the two main factors determining the air resistance of a group were the stocking density of the animals and their live weight (size). Stocking density is directly related to porosity (how much open space is left between animals), and live weight correlates with the body size (surface area) of the animals. A denser packing of animals or larger-bodied animals both increase the flow. Similarly, if animals are arranged in a line vs. scattered, or if there are gaps between them, the ease with which air can percolate through (or around) the group will change. The porous media resistance parameters must be tuned to capture the dominant influences of group configuration on airflow [

3,

13,

16]. Such findings reaffirm that multiple configuration parameters—not just the number of animals, but also their spatial distribution and size—significantly affect the pressure drop through an animal occupied zone.

When parameterizing animal groups as obstacles, another practical consideration is that the configuration is not static. Animal distribution inside the AOZ varies depending on the activities of the animals, related for example to the time of the day. So far in CFD modeling, it is often neglected that in real barns animals move around, change posture, and grow over time, while any fixed obstacle representation approximates only a transient situation. As animals move or adopt different postures, the porous medium’s tortuosity changes. As animals grow (or different breeds with larger/smaller bodies are considered), the blockage effect increases or decreases, modifying the effective porosity of the zone. In consequence, it is crucial to understand the range of possible resistance values to use porous media models with high accuracy compared to fully resolved geometries. Ultimately, to simulate robust ventilation or to predict emissions accurately, we need to account for how much the pressure drop can fluctuate as the animal layout evolves.

With our study we aim to quantify the sensitivity of airflow resistance to the arrangement and attributes of the animals acting as obstacles. Our primary objective is to evaluate the extent to which pressure drop through an AOZ differs under various animal configurations, and to estimate and quantify the impact on the flow pattern downstream. By that, we aim to evaluate whether a single porous media approximation is sufficient or if multiple sets of parameters (or adaptive parameters) are needed to cover the spectrum of real-world configurations.

The following two key hypotheses determine our investigation:

Tortuosity Hypothesis: Given the number of animals in the group (which corresponds to the porosity of the medium) as constant, the spatial alignment of animals in the group (which contributes to the tortuosity and the effective flow path lengths through the group) has a significant influence on the pressure drop across the group and on the flow pattern downwind of the group.

Size/Posture Effects Hypothesis: The physical size and shape of the obstacles—related to animal body size, breed, or posture (standing vs. lying)—have a significant impact on the pressure drop and the downstream airflow pattern. Larger or more aerodynamically “wide” animals block more air, causing higher pressure losses, while smaller or narrow-profile animals allow easier flow. For example, a group of heavy-breed cows (or cows lying on their side exposing a broad area) is expected to create a stronger wake and disturbance in the airflow than a group of lighter or narrower animals (or cows facing head-on), all else being equal.

By testing these hypotheses, our study will determine to what extent animal count vs. arrangement vs. size each contribute to airflow resistance. If the range of variability is small, one parameter set may suffice, but if it is large, the model may need to incorporate configuration-specific adjustments. Answering this question will ultimately lead to more robust, accurate, and efficient CFD predictions of barn climate and emissions when using porous modeling approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on a CFD model introduced by Doumbia et al. [

13] which was based on a preceding study of Bustos-Vanegas et al. [

3]. It uses simplified cow geometries composed of cylindrical objects. The simplification of cylindrical cow geometries builds on a previous study by Mondaca and Choi [

17], who showed that this approximation very well reproduces the flow patterns generated by detailed polygon cow models. At the same time, less meshing effort is required, which leads to a substantial reduction of preparation and computation time.

Lying and standing cows were distributed randomly within the AOZ. While in the original study only three angle positions of cows were implemented (15°, 30°, and 90°), in the present study, different sets of angle positions were permitted (any angle randomly chosen between 0° and 90°). In addition, in the original study [

13], the AOZ had the dimension of L

AOZ = 10.8 m, W

AOZ = 4.9 m, and H

AOZ = 1.6 m, consisting of 22 cows with a density of 2.4 m

2 cow

−1, following the same dimension as one of the AOZs in the prototype dairy barn in Dummerstorf [

18]. However, in order to allow cows more freedom in a random distribution within the AOZ and to more generalize the dimensions of the AOZ, in the present study, the AOZ was enlarged to accommodate 33 cows and had the width of the AOZ being half of the length of the AOZ, while keeping the cow density the same as in the original study, i.e., L

AOZ = 17.1 m, W

AOZ = 8.55 m, and H

AOZ = 1.6 m.

2.1. Numerical Model

As this study focused on investigating the effects of animal configurations on the pressure drop variations to provide information on a better characterization of porous media model of the AOZ, all CFD simulations were carried out based on an individual AOZ consisting of 33 cows with a density of 2.4 m

2 cow

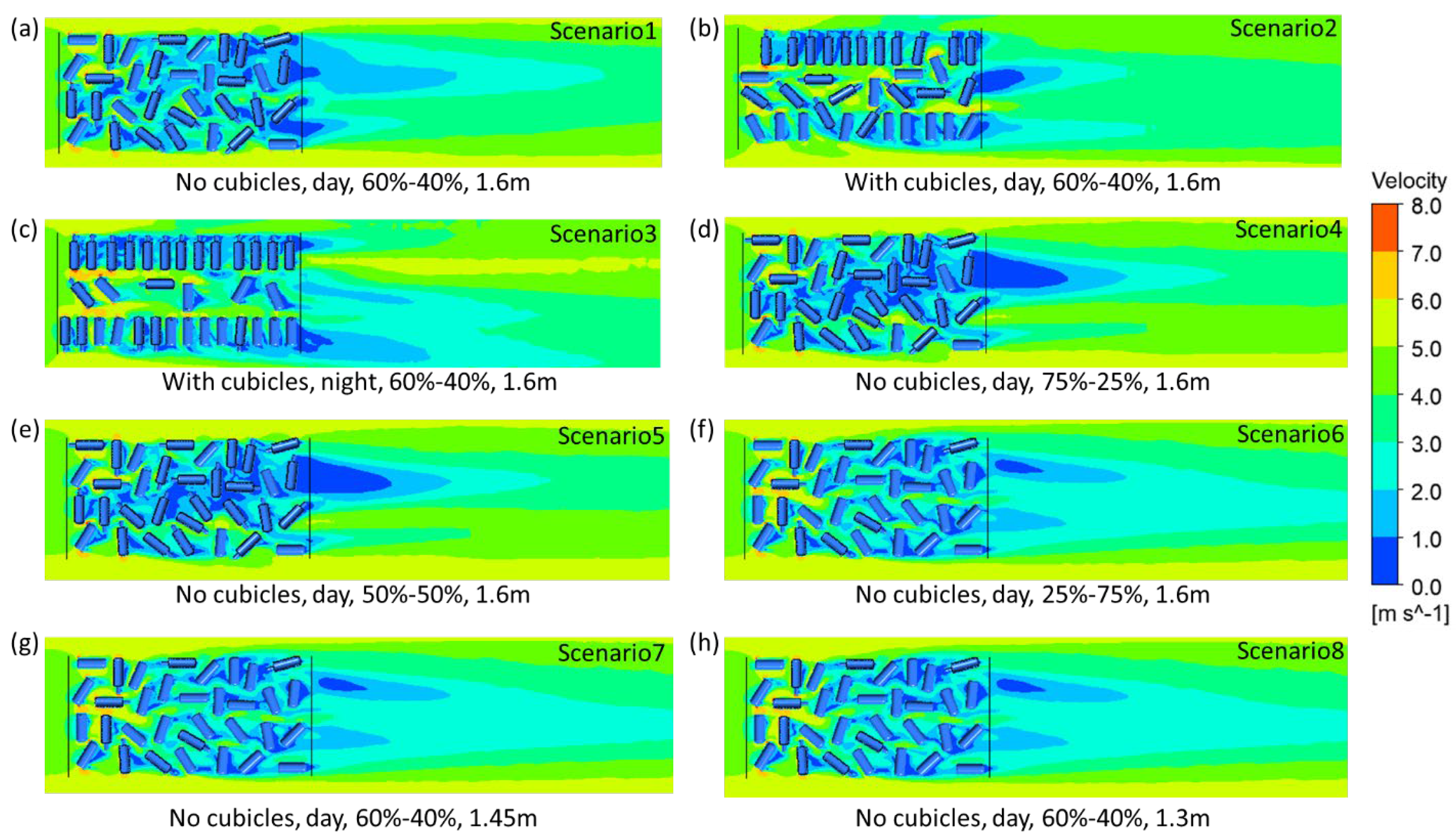

−1 without considering the entire housing system. The configurations of the AOZ varied for different scenarios, which are described in detail in

Section 2.3.

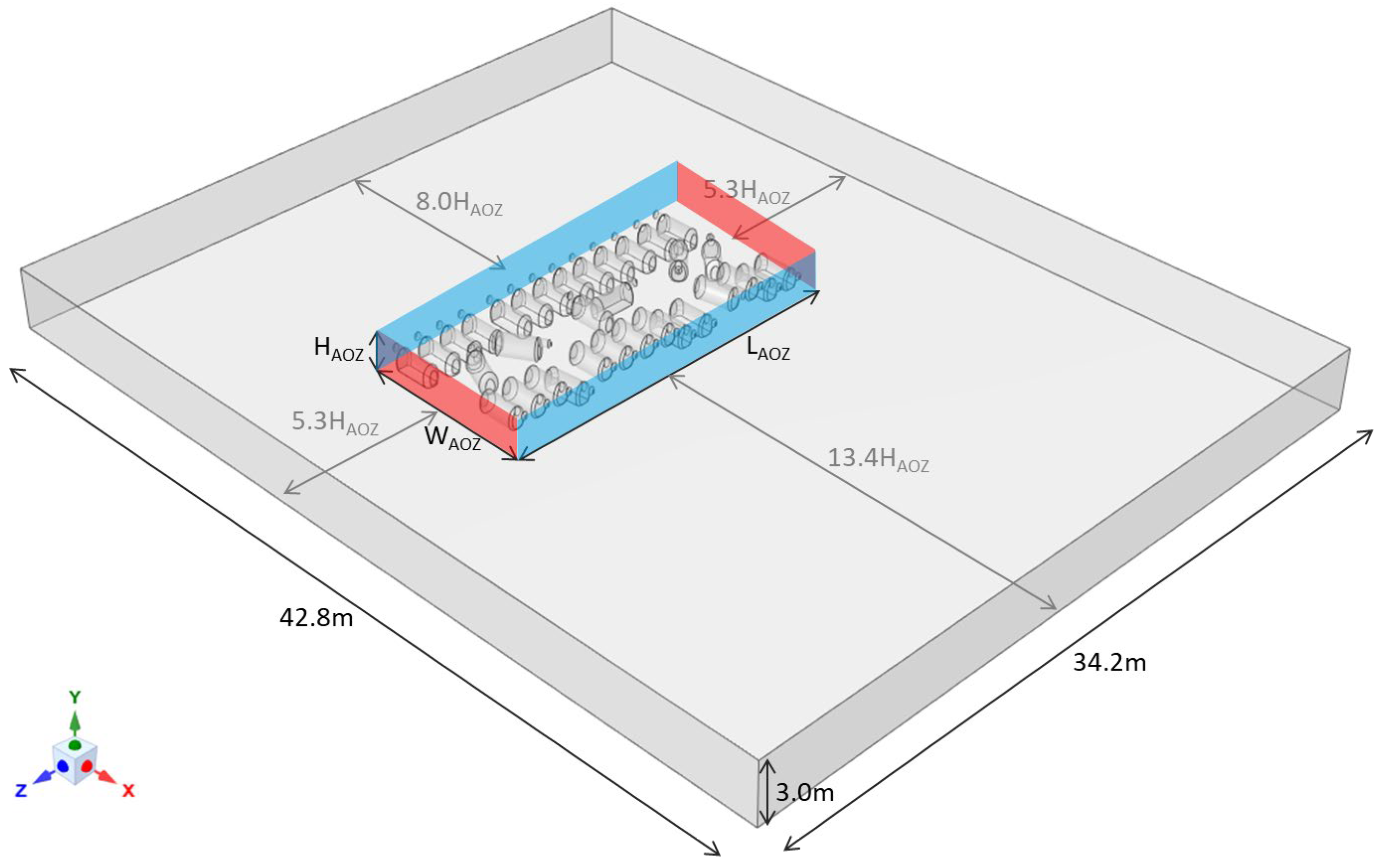

As shown in

Figure 1, the dimensions of the computational domain were length × width × height = 42.8 m × 34.2 m × 3.0 m, following the guidelines in the literature [

19], in which the front and lateral boundaries were greater than 5 H

AOZ away from the AOZ, and the downstream boundary were greater than 10 H

AOZ away from the AOZ. Instead of using the recommended value of 5 H

AOZ, the top boundary was shortened to 1.9 H

AOZ (i.e., 3 m) based on a preceding study that simulated the computational domain as a virtual wind tunnel with the height of 3 m [

3].

For each AOZ configuration, two wind directions of 0° and 90° and nine velocity magnitudes of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.2, 2, 3, 4, and 5 m s−1 were simulated. The front boundary was set to velocity inlet with constant velocity value in each case. The k and ω values were used for representing the turbulence. The downstream boundary was set to pressure outlet with zero static pressure. For the top, bottom, and lateral boundaries and the cows, a no-slip wall boundary was used. This study focused on the wind-driven ventilation conditions when the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor is small and therefore thermal buoyancy is neglectable.

As this study is based on our previous study [

13] using the same geometric models of the cows with the same cow density, the same meshing strategy was deemed valid and, thus, was adopted in this paper. Thus, the mesh convergence study was not repeated. In the final mesh used in this study, the minimum surface size was defined as 0.005 m on the ground surface, and 0.0005 m on the cows applying a mesh inflation with a maximum of 10 layers and a mesh growth rate of 1.2, in order to obtain a wall y+ smaller than one. The cell size around the AOZ and in the remaining domain were set to 0.4 m and 0.8 m, respectively. These resulted in a total cell number of 7,581,938 for the baseline case. Further details about the meshing and results of the mesh convergence study can be found in [

13].

The simulation setup was validated by comparing with the data from on-farm measurements of air velocities at nine locations at 3 m high inside the prototype dairy barn in Dummerstorf, which was not reachable by cows to prevent cows from damaging the sensors. For the validation case in the preceding study [

13] and the baseline case in the present paper, the dairy cow geometric models, cow density, AOZ height, and meshing strategies of the AOZ, as well as the turbulence model and numeric scheme, were kept the same. The results showed that the simulated and measured air velocity had the same direction except at one measurement location and had an RMSE of 0.04 m s

−1, indicating that the CFD model using 3D simplified cow geometries was considered valid for simulations. More details about the model validation can be found in the publication [

13]. The CFD validation procedure was not repeated in this study.

All simulations were run in steady state (time independent) and adiabatic (no heat transfer) mode using the software ANSYS (version 2022 R1) with the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations. The k-omega SST model was chosen as the turbulence model. The pressure velocity coupling scheme was set to couple to reach better convergence. The spatial discretization schemes were kept standard, which means second-order upwind for the momentum, turbulent kinetic energy, and the specific dissipation rate, and second-order for the pressure. As suggested by the Fluent user guide, convergence was considered as being achieved when the residuals were below 10−3 overall.

2.2. Pressure Drop of the AOZ

In classical porous media modeling, building on the theory of Henry Darcy, a momentum source term

Si is added to the governing equations of fluid flow:

with

and

.

Here, (∆Pi)/(∆xi) (Pa m−1) is the pressure drop per length unit in the direction xi of the Cartesian coordinate, μ (Pa s) is the air dynamic viscosity, Dij (m−2) is the viscous resistance, Fij (m−1) is the inertial resistance, ρ (kg m−3) is the air density, and ui (m s−1) is the velocity component. The first term, which is linear in the velocity, is characterized by the permeability of the porous medium, while the second term, which is quadratic in the velocity, reflects turbulence effects.

In the present study, we modeled the obstacles in different AOZ configurations explicitly and evaluated the pressure drop in order to evaluate effects of obstacle size and position on the resistance parameters that can be further used in porous modeling. The airflow was introduced in the two main Cartesian directions. The corresponding pressure drop, ΔPx and ΔPz, was evaluated by calculating the pressure difference between the planes upstream and downstream of the AOZ.

2.3. AOZ Variations

The AOZ models (dimensions L

AOZ = 17.1 m, W

AOZ = L

AOZ/2, H

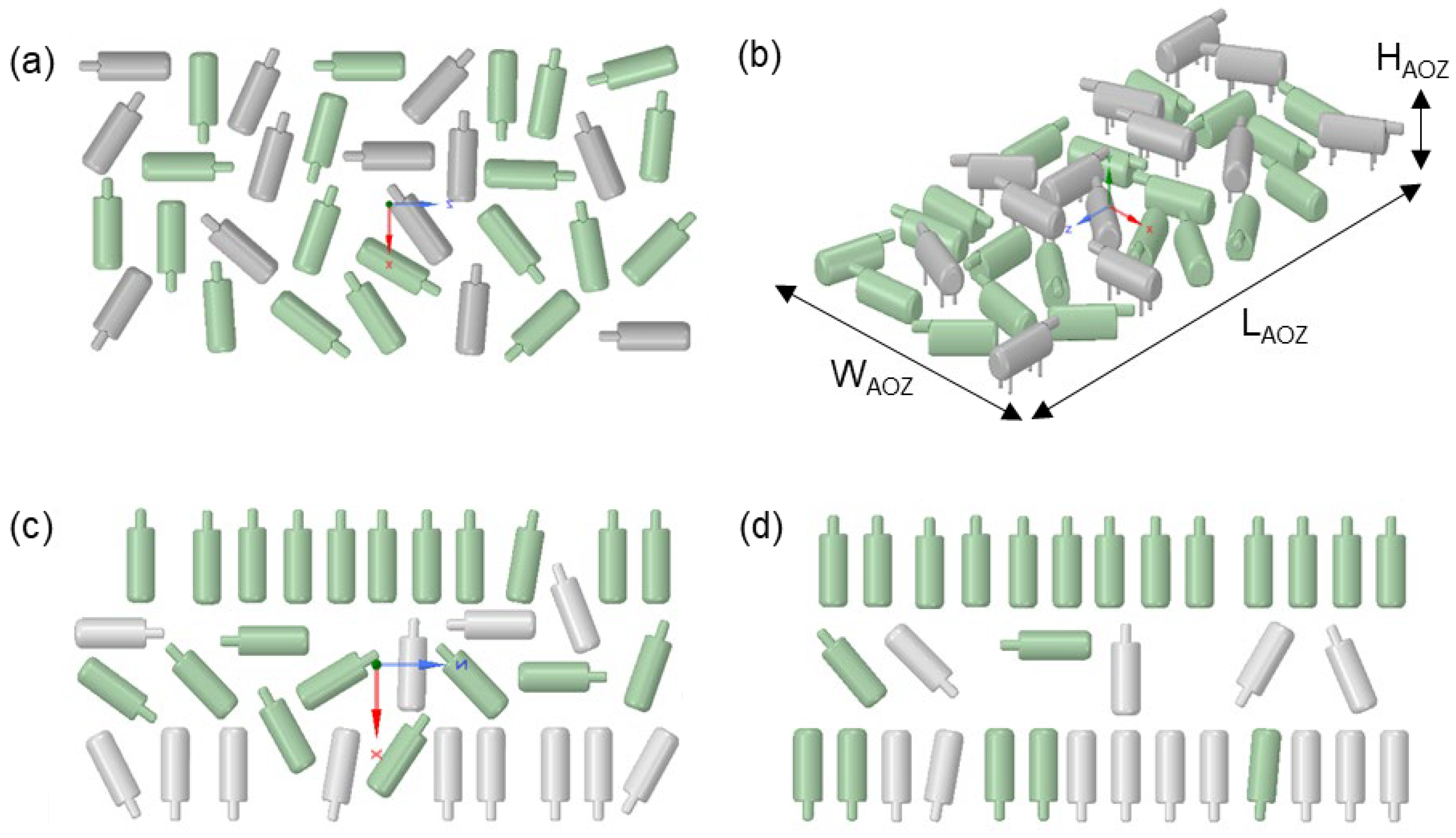

AOZ are varied upon different scenarios) are shown in

Figure 2. Three parameters of the configurations of the AOZ (cow positioning, lying–standing ratio, and cow breed) were investigated. Different sets of these parameter values resulted in a total of eight scenarios. As a baseline we considered a ratio of 60% in lying (in green) and 40% in standing (in gray) positions, as cows typically spend more than half the day lying per day [

20]. No cubicles, AOZ height of 1.6 m, and two wind directions were also considered in the baseline case.

Table 1 shows a summary of all designed scenarios.

2.3.1. Cow Position

The three AOZ configurations reflect typical spatial distribution characteristics of cows in loose housing without cubicles versus cubicle housing, where in the latter case we distinguish cow positioning during the day and at night (cf. Scenarios 1–3 in

Table 1).

In loose housing, the animals are allowed to move freely and have free access to all functional areas throughout the entire building; thus, they are also free to lie in the cubicles as they please or throughout the entire lying area in barns with unstructured free lying areas. In housing systems without cubicles, this implies a variety of possible angles between the main airflow direction and the animals in lying and standing position, which is reflected in the configuration “no cubicles” (Scenario 1). The “with cubicles” configuration (Scenarios 2 and 3) is where cubicles and beds have been installed inside the AOZ in order to create places to rest. In those systems, part of the variety in angles is lost as the animals are triggered to align parallel to each other in the cubicle. In the alley between the cubicles, the full range of angles may occur. The “with cubicles at night” configuration (Scenario 3) corresponds to a situation in cubicle housing with less activity, where cows lie inside the beds or are about to lie down there. Only a few animals are found in the alleys.

The porosity of the AOZ is the same in all three configurations; however, the tortuosity must be expected to differ which will affect the pressure drop. The tortuosity measures the effective length of the transport route through a porous medium and depends on the average angle between the main flow direction and the pores, while the porosity is defined by the animal density, which is constant throughout the scenarios.

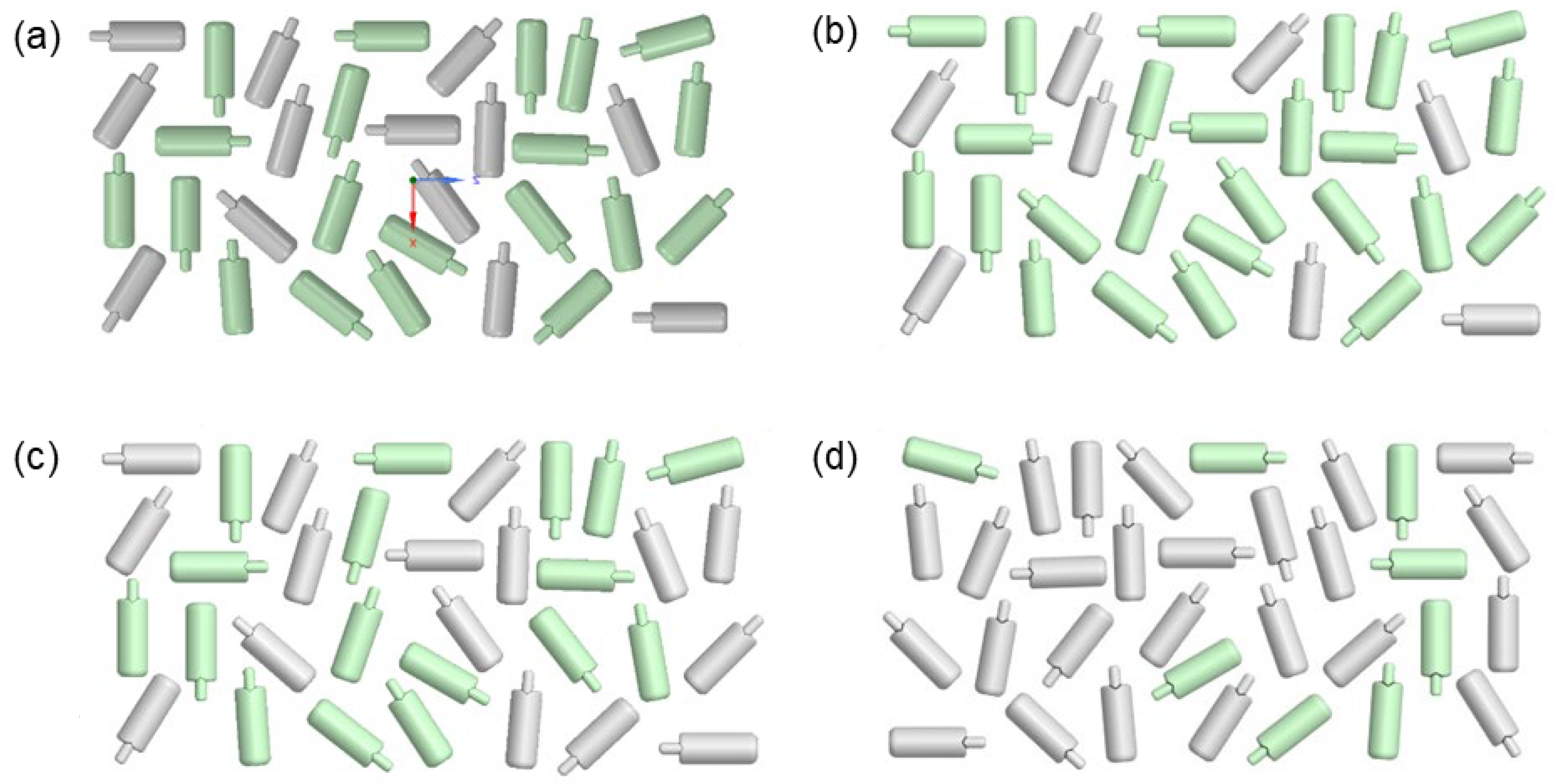

2.3.2. Cow Lying–Standing Ratio

The original AOZ is composed of 60% lying cows and 40% standing cows. The reasoning behind this was that cows spend, under thermo-neutral conditions, 10 to 14 h per day lying [

21]. However, the activity and location of cows differs during the day and in reaction to microclimatic conditions. Taking this variability into account, three additional lying–standing ratios for the AOZ configuration without cubicles were explored (cf. Scenario 4–6 in

Table 1). Those are 75% lying–25% standing, 50% lying–50% standing, and 25% lying–75% standing (where the latter may occur under very hot conditions) (

Figure 3).

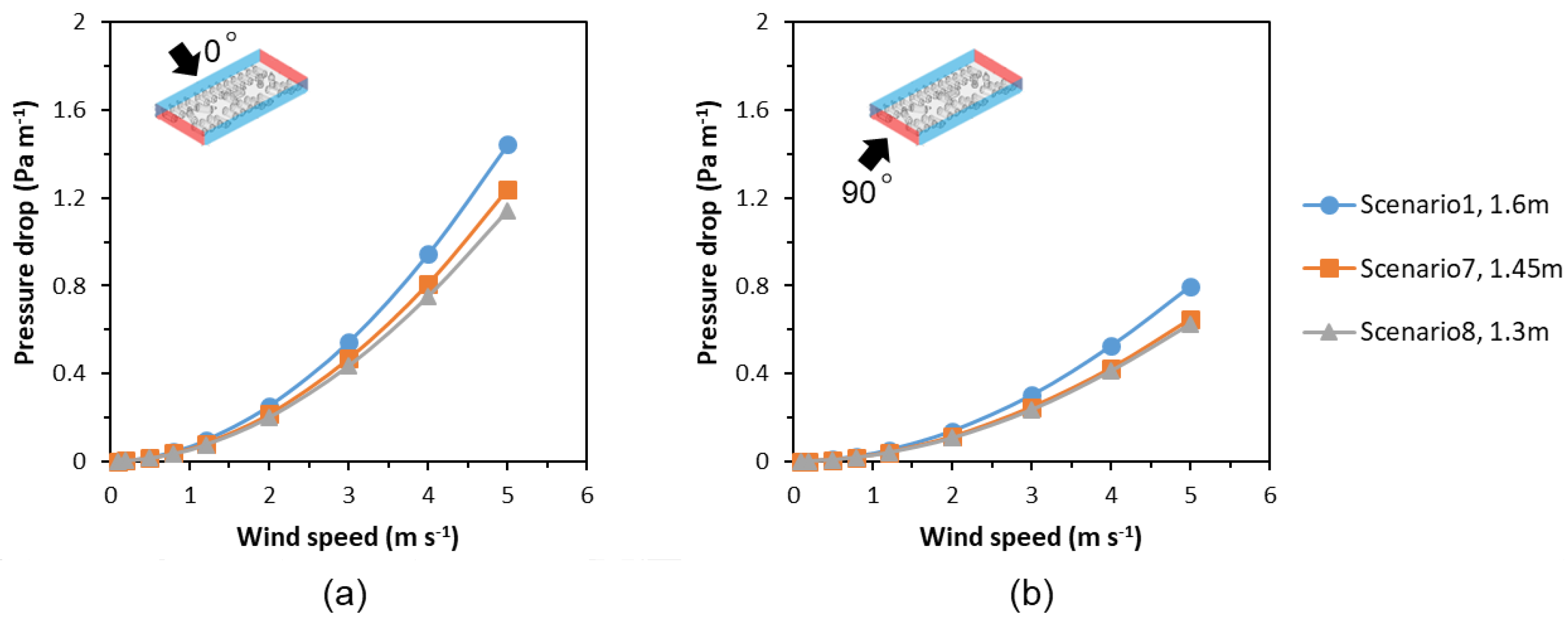

2.3.3. Cow Breed

The cow breed chosen for the original AOZ was Holstein Friesian (H

AOZ = 1.6 m), which is the widely used breed for dairy farming. However, there are other breeds that differ considerably in size and, thus, must be expected to affect pressure drop in a different way. In the present study we considered two additional breeds, the red Holstein (height H′

AOZ = 1.45 m) and jersey (H″

AOZ = 1.3 m) cattle (cf. Scenarios 7 and 8 in

Table 1). Those breeds were chosen because of their popularity around the world. Holstein breeds are globally the most important dairy cattle breed due to their high milk yields. The Red Holstein is, after the Holstein Friesian, particularly popular. The Jersey cattle breed is famous for its good feed efficiency and the high quality of the milk. The different body heights of these breeds result in a low-rise upper ceiling of the AOZ, which is about 90% of H

AOZ for Red Holstein and about 80% of H

AOZ for Jersey. Effects of each of these heights were simulated for the baseline scenario without cubicles.

4. Conclusions

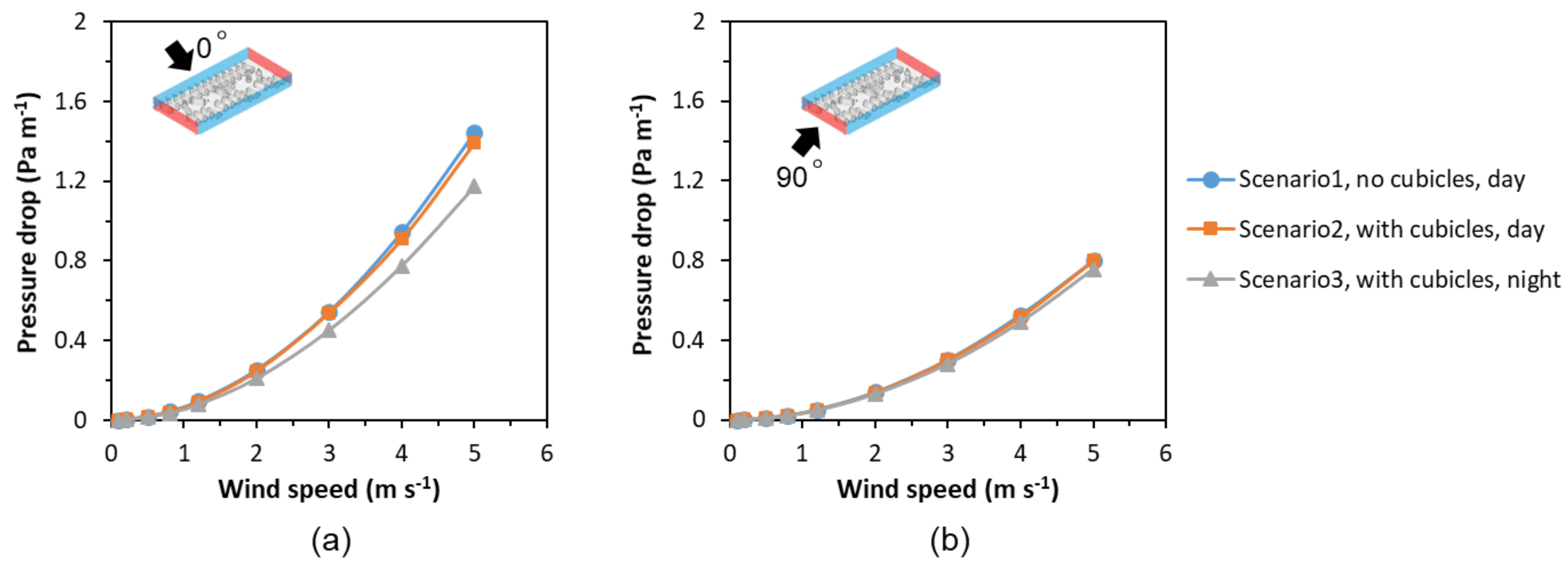

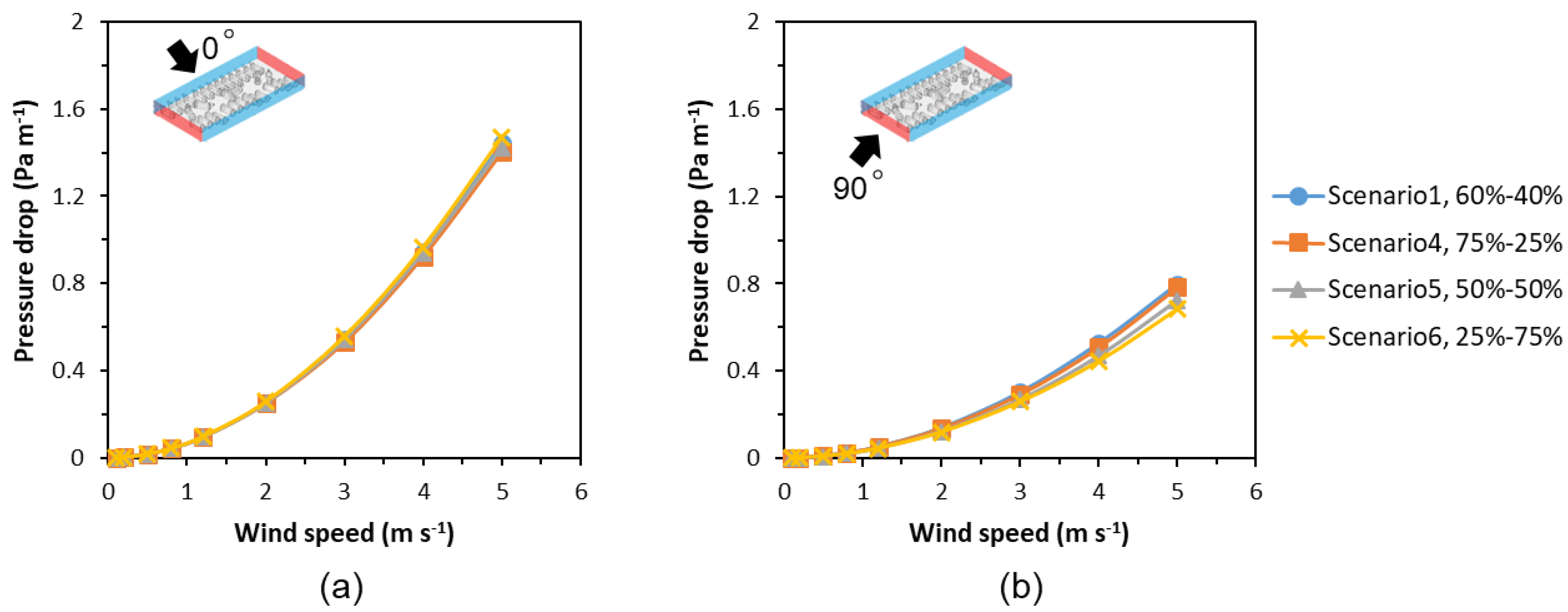

The range of variability in pressure drop per unit length associated with AOZ configurations, including cow spatial arrangement, cow lying–standing ratio, and cow breed at two wind directions, was studied. The following conclusions were drawn.

The pressure drop increased with the increasing wind speed for all scenarios. At 0° wind direction, higher pressure drop values were obtained than at 90° wind direction, reflected by higher viscous and inertial resistance. The cow position, in general, had little impact on the pressure drop at low wind speeds, while showing differences among different scenarios when the wind speed was over 2 m s−1, with the highest difference of 0.269 Pa m−1 between Scenario 1 and Scenario 3 at 5 m s−1 wind speed and 0° wind direction.

Cows distributed in a more organized alignment, i.e., in Scenario 3, showed less airflow resistance, and, therefore, a lower pressure drop and higher air velocities across the AOZ, which can be explained by shorter effective path lengths in such alignments. Those results confirm our tortuosity hypothesis.

We further found that the cow breed affected the pressure drop, with higher AOZ showing higher pressure drop and air resistance. In contrast, it was found that the effects of cow lying–standing ratio on the pressure drop and airflow resistance coefficients were negligible, with a maximum deviation of 6.3% at 0° wind direction. This is likely related to the fact that the overall blocking potential is similar in both cases and the distribution of lying and standing cows affects the air resistance (e.g., if standing and lying cows alternate, the effective path length for the flow increases, while a row of only standing or only lying cows may be associated with similar path lengths). In consequence, the initial size–posture hypothesis could be only partly confirmed in this study.

Representing the AOZ with the porous medium and using the resistance coefficient derived by this study supports the setup of more accurate CFD models. However, our study primarily supports the importance of tortuosity, while the porosity effects were not investigated. In order to understand the influence of the effective path length through the AOZ in different scenarios in more detail, future investigations are needed to calculate the tortuosity of each AOZ configuration and to explore the sensitivity of the resistance coefficients to the deviations in cow orientation and spacing. Moreover, the present study only considered wind-driven ventilation conditions at two main wind directions, which limits the applicability of the obtained flow resistance only to the situations similar to the investigated scenarios. Future studies that consider the buoyancy effects and a broader range of wind directions will be conducted. Meanwhile, the directional anisotropy of viscous resistance and inertial resistance will be explored in future work. By that, it will become feasible to determine more accurate resistance coefficients for different configurations without the need to explicitly simulate distinct AOZ configurations.