Environmental Enrichment Attenuates Acute Noise-Induced Bursal Injury in Broilers via Suppressing NF-κB and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Laboratory Animals and Husbandry Management

2.3. Experimental Animal Grouping and Sample Collection

2.4. Histopathological Examination and Ultrastructural Analysis

2.5. Oxidative Stress Marker Detection

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.7. TUNEL Assay

2.8. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.9. Western Blot

2.10. Immunofluorescence Double Staining

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Histological Observations

3.2. Effects of Acute Noise Exposure on Antioxidant Activity in the Bursa of Fabricius Tissue of Broiler Chickens

3.3. Effects of Short-Term Music Intervention on Acute Noise-Induced Inflammatory Damage in the Bursa of Fabricius of Broilers

3.4. Long-Term Music Exposure Suppresses Acute Noise-Induced Activation of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway

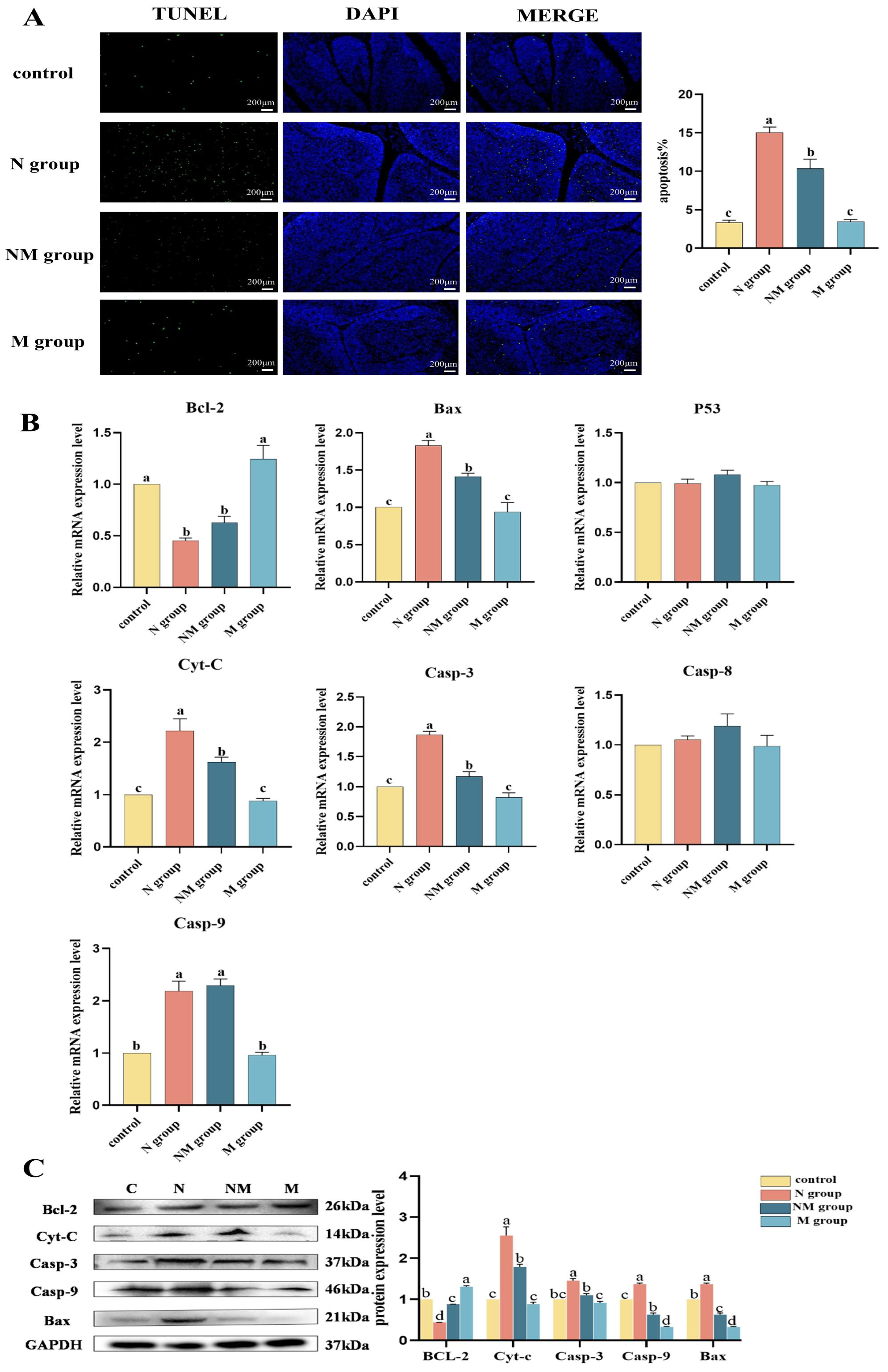

3.5. Analysis of Apoptotic Molecule Expression in Bursa of Fabricius Tissue and TUNEL Assay

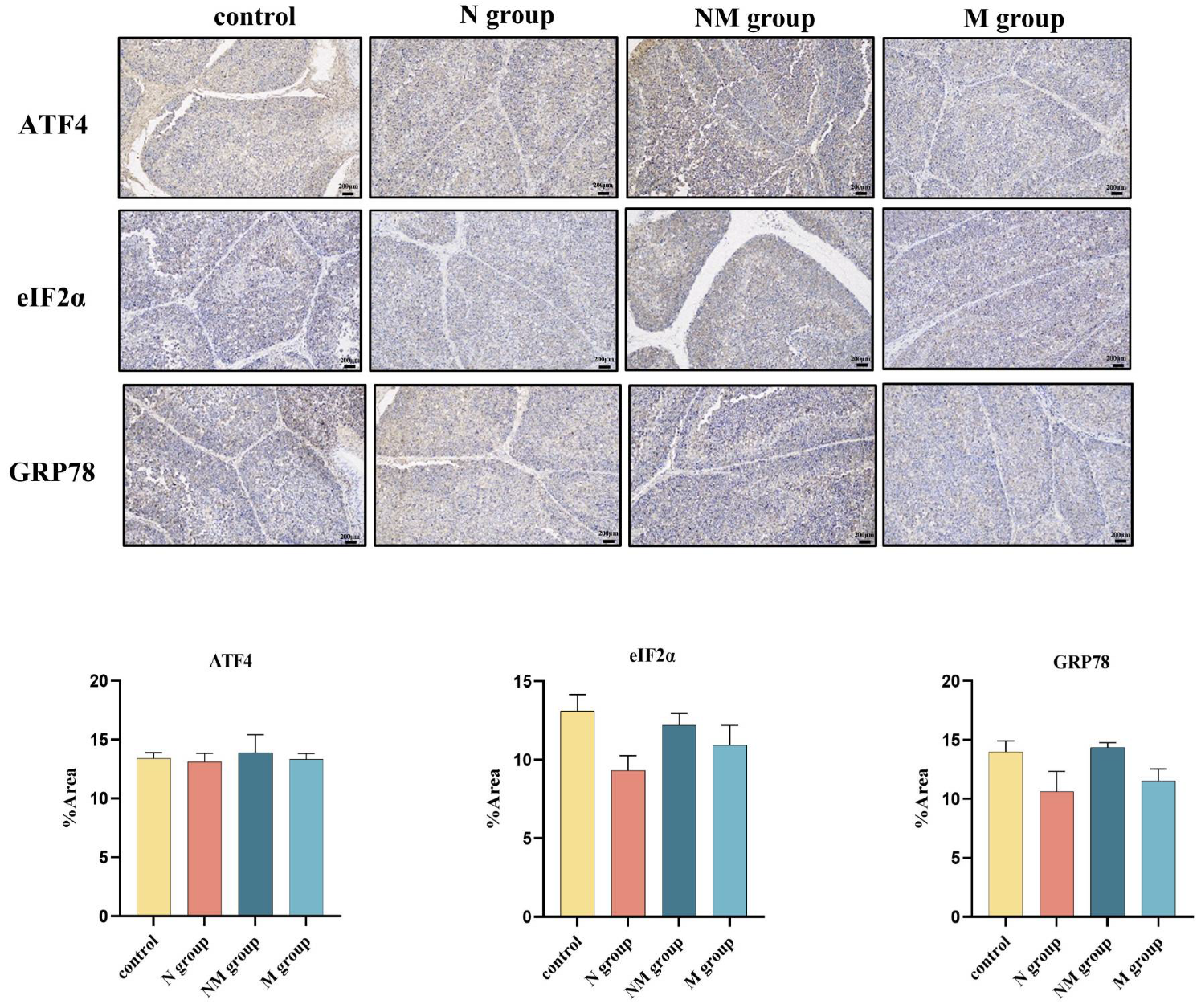

3.6. No Significant Effect of Acute Noise on Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Protein Expression in the Bursa of Fabricius

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amjad, R.; Ruby, T.; Ali, K.; Asad, M.; Imtiaz, A.; Masood, S.; Saeed, M.Q.; Arshad, M.; Talib, S.; Alvi, Q.A.; et al. Exploring the effects of noise pollution on physiology and ptilochronology of birds. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregi, A.; Vegas, O.; Lertxundi, A.; Silva, A.; Ferreira, I.; Bereziartua, A.; Cruz, M.T.; Lertxundi, N. Road traffic noise exposure and its impact on health: Evidence from animal and human studies-chronic stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress as key components of the complex downstream pathway underlying noise-induced non-auditory health effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46820–46839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Bao, J. Prolonged exposure to a music-enriched environment mitigates acute noise-induced inflammation and apoptosis in the chicken spleen by modulating the Keap-1/Nrf2 and NF-kappaB pathways. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmati, S.; Sadeghi, S.; Moosazadeh, M. Oxidative stress markers in occupational noise exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2025, 98, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gutierrez, D.E.; Guthrie, O.W. Systemic health effects of noise exposure. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 2024, 27, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalikova, D.; Stamm, P.; Kvandova, M.; Pednekar, C.; Strohm, L.; Ubbens, H.; Oelze, M.; Kuntic, M.; Witzler, C.; Bayo, J.M.; et al. Exposure to aircraft noise exacerbates cardiovascular and oxidative damage in three mouse models of diabetes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S.G.; Galatos, A.D. Music as a perioperative, non-pharmacological intervention in veterinary medicine. Establishing a feasible framework for music implementation and future perspectives with a focus on the perioperative period of dogs and cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1672783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, J. The effect of Mozart’s K.448 on epilepsy: A systematic literature review and supplementary research on music mechanism. Epilepsy Behav. E&B 2025, 163, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, Y.; Meng, H.; Liu, Y.; Mayer, J.; Campbell, N.; Wright, C.; Amidei, A.; Butail, I.; Fields, S.; Green, M.; et al. Effects of classical music on behavioral stress reactivity in socially isolated prairie voles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, 1553, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Feng, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Gu, S.; Ma, N. Effects of Raga music and Chinese five-element on milk production, antioxidant, neuroendocrine, immune, and welfare indicators in dairy cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1623026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Rethinking Poultry Welfare—Integrating Behavioral Science and Digital Innovations for Enhanced Animal Well-Being. Poultry 2025, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szocs, E.; Balic, A.; Soos, A.; Halasy, V.; Nagy, N. Characterization and ontogeny of a novel lymphoid follicle inducer cell during development of the bursa of Fabricius. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1449117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; Cavaleiro, C.L.C.T.; Berghof, T.V.L.; von Heyl, T.; Alhussien, M.N.; Wurmser, C.; Elleder, D.; Schusser, B. Transcriptome analysis identifies CCR7 and cell adhesion molecules as mediators of B cell migration to the bursa of Fabricius during chicken embryonic development. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahad, O.; Kuntic, M.; Al-Kindi, S.; Kuntic, I.; Gilan, D.; Petrowski, K.; Daiber, A.; Muenzel, T. Noise and mental health: Evidence, mechanisms, and consequences. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, A.; Shukla, S.P.; Shukla, A.K.; Manar, M.K.; Singh, S.K.; Mehrotra, M. A Comprehensive Review of Auditory and Non-Auditory Effects of Noise on Human Health. Noise Health 2024, 26, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Kang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, F.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, J. Acute high-intensity noise exposure exacerbates anxiety-like behavior via neuroinflammation and blood brain barrier disruption of hippocampus in male rats. Behav. Brain Funct. 2025, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Causal effects of noise and air pollution on multiple diseases highlight the dual role of inflammatory factors in ambient exposures. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, C.Y.; Shityakov, S.; Stavrakis, S.; Scheper, V.; Lenarz, T. Interplay between noise-induced sensorineural hearing loss and hypertension: Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1523149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingle, Y.P.; Ragha, L.K. An in-depth analysis of music structure and its effects on human body for music therapy. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 45715–45738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuri, K.; Bind, R.H.; Rebecchini, L. The role of music in perinatal mental health, with a psychoneuroimmunological perspective. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2025, 48, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, L.; Luo, Z.; Sun, R. Music therapy in modulating immune responses and enhancing cancer treatment outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1639047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.A.; Bagg, M.K.; Harvey, A.R. The psychophysiology of music-based interventions and the experience of pain. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1361857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallazzi, M.; Pizzolante, M.; Biganzoli, E.M.; Bollati, V. Wonder symphony: Epigenetics and the enchantment of the arts. Environ. Epigenetics 2024, 10, dvae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Yin, M.; Sun, P.; Ding, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sun, P.; Xia, W.; et al. Potential common targets of music therapy intervention in neuropsychiatric disorders: The prefrontal cortex-hippocampus—Amygdala circuit (a review). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1471433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Jin, F.; Lin, Z.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. The development, degeneration and immune function fate of bursa of Fabricius in the widely distributed altricial tree sparrow. Zoomorphology 2025, 144, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghari, F.; Zhang, H.; He, C.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J.; Chang, Q.; Bao, J.; Zhang, R. Resveratrol alleviates stress-associated bursal injury in chickens: A transcriptomic analysis. Brit Poultry Sci. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, R.J.; Casey, M.A.; Camp, E.J.; Meisenhelter, S.; Steimel, S.A.; Song, Y.; Testorf, M.E.; Leslie, G.A.; Bujarski, K.A.; Ettinger, A.B.; et al. Musical components important for the Mozart K448 effect in epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Qiu, R.; Yao, T.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, W.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y. Music therapy as a preventive intervention for postpartum depression: Modulation of synaptic plasticity, oxidative stress, and inflammation in a mouse model. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P. Programmed cell death in tumor immunity: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1309635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, R.; Tantry, I.Q.; Ahmad, W.; Siddiqui, S.; Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Hassan, M.I.; Habib, S.; Islam, S. Apoptosis: A Comprehensive Overview of Signaling Pathways, Morphological Changes, and Physiological Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2024, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallam, J.; Burton, P.; Sanders, K. Poor Sperm Chromatin Condensation Is Associated with Cryopreservation-Induced DNA Fragmentation and Cell Death in Human Spermatozoa. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadri, P.; Zahmatkesh, A.; Bakhtari, A. The potential effect of melatonin on in vitro oocyte maturation and embryo development in animals. Biol. Reprod. 2024, 111, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Ubosi, N.I.; Obeagu, G.U.; Egba, S.I.; Bluth, M.H. Understanding apoptosis in sickle cell anemia patients: Mechanisms and implications. Medicine 2024, 103, e36898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Long, Y.; Tan, G.; Li, X.; Xiang, B.; Tao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X. Programmed cell death: Molecular mechanisms, biological functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X. Progress in Understanding Oxidative Stress, Aging, and Aging-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, A.; Xiao, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Yi, J.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis: A novel mechanism of citrinin-induced renal injury and dysfunction. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe 2024, 284, 116946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettel, P.; Karagoz, G.E. Endoplasmic reticulum: Monitoring and maintaining protein and membrane homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum by the unfolded protein response. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B 2024, 172, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmig, P.; Diaz, M.; Zheng, J.; Williams, C.C.; Lang, A.; Aragon, T.; Li, H.; Walter, P. The unfolded protein response in fission yeast modulates stability of select mRNAs to maintain protein homeostasis. Elife 2012, 1, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Jimenez, M.A.; Sharma, S.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. The integrated stress response in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yang, J.Q.; Tong, S.; Xu, L.; Dong, N.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Yao, R.Q.; Yao, Y.M. FAM134B in Cellular Homeostasis: Bridging Endoplasmic Reticulum-Phagy to Human Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 5514–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, P.; Lu, L.; Yi, T.; Li, Y.; Mao, W.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, K. A study on expression of GRP78 and CHOP in neutrophil endoplasmic reticulum and their relationship with neutrophil apoptosis in the development of sepsis. J. Biosci. 2024, 49, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grando, K.; Bessho, S.; Harrell, K.; Kyrylchuk, K.; Pantoja, A.M.; Olubajo, S.; Albicoro, F.J.; Klein-Szanto, A.; Tukel, C. Bacterial amyloid curli activates the host unfolded protein response via IRE1 in the presence of HLA-B27. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2392877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibody | Dilution Ratio | Source |

|---|---|---|

| NF-κB P65, IKB, IKK, IFN-γ | 1:300 | Wanlei, China |

| Bcl-2, Cyt-C, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, Bax | 1:1000 | ABclonal, China |

| GAPDH | 1:2000 | Servicebio, China |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Wang, H.; He, C.; Zhang, R.; Luo, C. Environmental Enrichment Attenuates Acute Noise-Induced Bursal Injury in Broilers via Suppressing NF-κB and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways. Agriculture 2026, 16, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010078

Li M, Wang H, He C, Zhang R, Luo C. Environmental Enrichment Attenuates Acute Noise-Induced Bursal Injury in Broilers via Suppressing NF-κB and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Min, Haowen Wang, Chunye He, Runxiang Zhang, and Chaochao Luo. 2026. "Environmental Enrichment Attenuates Acute Noise-Induced Bursal Injury in Broilers via Suppressing NF-κB and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010078

APA StyleLi, M., Wang, H., He, C., Zhang, R., & Luo, C. (2026). Environmental Enrichment Attenuates Acute Noise-Induced Bursal Injury in Broilers via Suppressing NF-κB and Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathways. Agriculture, 16(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010078