1. Introduction

As the fourth largest food crop in China, potato serves both as a staple and a vegetable, and is valued for its remarkable adaptability and significant economic potential [

1]. High-quality seed potatoes can substantially enhance both the yield and quality of potatoes, boost market competitiveness, and deliver greater economic benefits to growers [

2]. Seed potatoes are vulnerable to pathogen infections and environmental stresses throughout cultivation, harvesting, transportation and storage, often resulting in various external defects that severely compromise planting efficiency and quality standards. Prompt identification and removal of defective seed potatoes are essential for preserving planting efficiency. In practice, defect screening largely depends on manual visual inspection, which is labor-intensive, subjective, and inefficient [

3]. Consequently, the development of automated, non-destructive detection technologies is vital for improving the efficiency of external defect detection in seed potatoes.

In potato production, high-quality ware potatoes are usually used as retained seed stock [

4]. As such, methodologies for inspecting the quality of ware potatoes offer valuable guidance for this study. Currently, potato defect detection technologies mainly include machine vision-based object detection, traditional near-infrared spectroscopy, and hyperspectral imaging. Xu et al. [

5] proposed a lightweight DATW-YOLOv8 model for potato defect detection by optimizing network modules and the detection head and introducing the Wise-EIoU loss, resulting in improved feature extraction and detection accuracy. Wang et al. [

6] applied deep transfer learning to potato surface defect detection by fine-tuning SSD Inception V2, RFCN ResNet101, and Faster R-CNN ResNet101, achieving enhanced detection performance. Imanian et al. [

7] combined Vis, NIR, and SWIR spectroscopy with intelligent algorithms to identify internal potato defects, selecting optimal wavelengths and achieving effective classification performance. Guo et al. [

8] used Vis/NIR spectroscopy combined with an improved ResNet model to detect potato black heart disease, achieving an accuracy of 0.971. Although machine vision-based object detection has made certain progress in identifying external defects of potatoes, it mainly relies on RGB image features such as color, shape, and texture, making it difficult to reflect internal chemical information. Furthermore, detection accuracy is susceptible to lighting conditions and surface reflections, and the algorithms are relatively complex with longer response times [

9,

10]. In contrast, traditional near-infrared spectroscopy enables non-destructively acquire the internal chemical properties of potatoes, making it suitable for detecting internal defects such as black heart disease. However, its spectral data lack spatial distribution information, limiting the ability to detect external defects and surface textures.

Hyperspectral technology integrated with machine learning has become well-established in agricultural product inspection and has demonstrated strong performance in detecting external defects [

11]. Hyperspectral imaging technology has the advantage of simultaneously acquiring spectral and spatial information of a target, representing its chemical composition and surface morphology, respectively [

12]. Zhao et al. [

13] combined hyperspectral spatial information with PCA and image processing, using a Bayesian classifier and BP neural network to detect potato defects. Al Riza et al. [

14] used multispectral images with preprocessing and pseudo-color transformation to enhance contrast among defects, normal skin, and soil, effectively reducing soil interference. Ji et al. [

15] used linear discriminant analysis to reduce spectral dimensionality and combined a multi-class SVM with K-means clustering to identify six potato defect types, achieving 90% test accuracy. Zhang et al. [

16] built a CNN model to detect the incubation period of potato dry rot, significantly improving accuracy compared with four traditional machine learning methods. Zhao et al. [

17] applied SG smoothing and standard normal variate preprocessing with K-nearest neighbor to detect normal, green-skin, and scab potatoes, achieving accuracies of 93%, 93%, and 83%, respectively. These studies confirm the feasibility of using hyperspectral technology to detect external defects in potatoes. However, existing methods specifically for seed potato defect detection mainly rely on single-dimensional information and fail to fully exploit the features of hyperspectral data, which still poses certain limitations in identifying subtle or morphologically similar defects.

At present, research on integrating spectral and spatial multidimensional information to enhance accuracy in the detection of external potato defects remains limited. Jin et al. [

18] proposed a detection method based on fused information, which combines diffusion map manifold learning with extreme learning machine. Compared with traditional machine learning, deep learning can automatically extract key features from hyperspectral data through its multilayer structure, reducing reliance on manual feature selection and more effectively exploiting high-dimensional deep information. Among them, the one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1DCNN) is suitable for processing sequential data and has good application potential in hyperspectral analysis [

19].

This study proposes a method for detecting external defects in seed potatoes based on spectral–spatial fusion of hyperspectral images and deep learning. This method acquires three-dimensional hyperspectral data of seed potatoes, separately extracts spectral data and spatial texture data, and fuses them after individual processing. Further, traditional machine learning models are compared with deep learning models to select the optimal one, achieving efficient and non-destructive detection of six types of defects—decay, mechanical damage, wormholes, common scab, black scurf and frostbite—providing theoretical basis and technical support for automated seed potato sorting systems.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Spectral Analysis of Different Defect Regions in Seed Potatoes

The near-infrared spectral region primarily reflects the overtone and combination vibration characteristics of hydrogen-bearing groups within molecules [

38]. Different regions of seed potatoes exhibit distinct spectral characteristics due to variations in their chemical composition, and these characteristics are closely related to the vibration modes of specific functional groups. A deeper absorption trough signifies a higher content of the corresponding functional group, characterized by stronger stretching vibrations and greater light absorption. Conversely, a higher reflection peak indicates that the light is predominantly reflected rather than absorbed, suggesting weaker vibrations of the associated functional group and a lower concentration.

Figure 5 shows the original overall spectral curves and the average spectral curves for each type of region.

These are derived from the figure above: (1) Distinct absorption troughs appear near 950 nm, 1180 nm, and 1450 nm in the spectral curves, corresponding to stretching vibrations of O-H triple frequency (moisture), C-H triple frequency (starch), and O-H double frequency (moisture), respectively [

35]. The reflection peak near 1070 nm is associated with a weaker N-H triple frequency (protein) vibration, leading to increased reflectance [

39]. (2) The spectral curves for decay and common scab areas are generally higher overall. This is due to microbial and pathogenic degradation of proteins, resulting in reduced protein content [

40]. Cell wall degradation in rotten areas releases bound water and inhibits water evaporation, increasing free water content and leading to higher humidity compared to diseased areas [

41]. (3) The spectral curve of the frostbitten area resembles that of the normal area but exhibits lower overall reflectance. This occurs because frostbite causes cellular dehydration and tissue softening [

42], leading to greater light absorption rather than reflection. (4) Spectral curves of wormholes and mechanically damaged areas exhibit similarities, as surface physical damage creates holes or cracks that expose tissue to oxidation, leading to comparable chemical composition changes. Within the 935–1140 nm range, normal areas show higher reflectance than wormholes and mechanically damaged areas, while the opposite holds true in the 1140–1721 nm range. This primarily stems from spectral differences caused by protein release, starch degradation, and moisture loss [

15]. (5) The spectral curve of the black scurf disease area exhibits a relatively flat peak near 1180 nm, with an overall trend similar to that of the common scab area but lower reflectance. This may be related to surface structural changes caused by fungal infection in both cases, though they differ in surface texture [

43]. The sclerotia of black scurf disease form black, hard particles on the surface of seed potatoes, rich in pigments and complex organic compounds [

44]. These particles absorb more light, thereby reducing reflectance.

3.2. Preprocessing Method Selection and Comparative Analysis

PLS-DA was applied to the spectral data to select the optimal preprocessing method, the results are shown in

Table 3, with OSC achieving the best classification performance. After OSC preprocessing, the OA, Pr, Re, and F1 on the validation set were 89.39%, 92.04%, 84.71%, and 86.61%, respectively, all showing improvement compared with the raw data. OSC employs orthogonal signal correction theory to eliminate systematic variations unrelated to classification while preserving critical spectral information [

45]. In contrast, SNV and MSC primarily eliminate scattering effects and baseline drift but may weaken some useful spectral features. FD and SD can enhance spectral details through derivative computation but may also amplify high-frequency noise, reducing data stability.

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction Based on PCA and Texture Feature Extraction

The metadata file of the hyperspectral image was first imported, and the mean value of each spectral band was computed to convert the original hyperspectral data into a grayscale representation. Subsequently, an Otsu thresholding method was applied to generate a mask, removing the background and retaining only the potato region. The three-dimensional hyperspectral data were then flattened into a two-dimensional matrix (number of pixels × number of bands), and PCA was performed to extract the first four principal component images (PC1–PC4). As shown in

Figure 6, the contribution rates of the first four principal components were 90.63%, 7.89%, 1.19%, and 0.12%, respectively. While the cumulative contribution of the first three PCs exceeded 99%, indicating their strong capacity for preserving the majority of the original hyperspectral data’s variance. Considering this high information content and the practical need for computational manageability in texture analysis, subsequent texture feature extraction was performed on these first three principal component images.

When establishing ROIs, select different types of regions to generate corresponding extensible markup language (.xml) files for recording pixel coordinates. Based on these coordinates, the GLCM was calculated to extract six texture features in four directions at a spatial distance of 1, yielding a total of 24 parameters. In combination with the three principal component images, 72 texture parameters were extracted for each ROI. This extraction procedure was consistent with the method described in

Section 2.3.2. Finally, all extracted data were normalized and stored as structured files for subsequent data fusion and modeling analyses.

To compare the differences between spectral data and spatial texture data in the feature space, PCA was applied separately to each data type for dimensionality reduction, followed by 3D and 2D visualization. As illustrated in

Figure 7, the two data types are distinguished by different colors. The results indicate that the distributions of spectral and spatial data in the principal component space are clearly separated. In particular, the PC1/PC2 plane exhibits minimal overlap, demonstrating that the first two principal components effectively capture the primary differences between the two feature types. This highlights the complementary nature of spectral and spatial features in information representation, providing a theoretical basis for data fusion.

3.4. Performance Comparison of Traditional Machine Learning Models

After OSC preprocessing, the spectral data were subjected to feature wavelength selection using the SPA and CARS. SPA aims to minimize the root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSECV) while balancing the number of variables and model simplicity. When the RMSECV decreased to 1.16, a total of 37 feature wavelengths were selected, as shown in

Figure 8a.

The variations of the parameters during the CARS process are illustrated in

Figure 8c–e. The lowest RMSECV was achieved at the 22nd sampling iteration, resulting in the selection of 30 feature wavelengths. The paths of the regression coefficient indicated that the selected wavelengths exhibited stable coefficients, demonstrating good robustness. The detailed feature selection results of CARS are presented in

Figure 8b.

The wavelengths selected by both methods were mainly concentrated in the ranges of 950–1100 nm and 1300–1700 nm, which are to some extent associated with the characteristic vibrations of hydrogen-containing groups in substances such as moisture, starch, and protein.

Based on the feature wavelength subsets selected by SPA and CARS, five traditional machine learning classification models—SVM, ELM, PLS-DA, RF, and KNN—were constructed. As shown in

Table 4, the CARS–ELM model achieved the best overall performance, with the highest OA of 94.44%, Pr of 94.62%, Re of 91.68%, and F1 of 92.66%. After feature wavelength selection, the reduced input dimensionality led to shorter training times for all models compared with the original data. The hyperparameter settings for each model are shown in

Table 5.

The ELM model initializes the weights between the input and hidden layers randomly and computes the output weights in a single step, making it sensitive to noisy wavelengths. The CARS algorithm reduces data redundancy and enhances the linear mapping capability of ELM, thereby improving the effectiveness of hidden-layer nodes. In contrast, the wavelengths retained by SPA may contain nonlinear noise, which can adversely affect model performance.

The overall performance of SVM, PLS-DA, RF, and KNN was relatively weaker, which can be attributed to limitations in feature adaptability and model mechanisms. PLS-DA relies on linear mapping for classification and struggles to capture the strong nonlinear relationships inherent in spectral data, resulting in limited discriminative ability. Without feature wavelength selection, its OA and F1 were 89.39% and 86.61%, respectively, and showed little improvement after applying SPA or CARS, indicating that linear models are insensitive to redundant or nonlinear information and fail to fully exploit spectral variability. RF is an ensemble of multiple decision trees which is sensitive to high-dimensional and highly correlated features. Regardless of using full-spectrum or selected feature wavelengths, its OA remained around 81–83% and F1 around 69–74%, suggesting that redundant wavelengths and correlated bands constrain tree-splitting effectiveness and reduce discriminative power. Moreover, excessive feature numbers increase model complexity, making certain nodes more susceptible to noise-induced misclassification. KNN classifies samples based on distance metrics, but in high-dimensional spectral space, data sparsity and noisy wavelengths blur class boundaries. Although SPA-based feature wavelengths selection slightly improved its performance (OA = 88.64%, F1 = 84.88%) by reducing redundancy and enhancing local discrimination, its overall performance remained inferior to ELM and SVM. The performance of SVM depends on the kernel type and hyperparameters

C and

γ. With CARS-selected feature wavelengths, its OA decreased to 87.12%, lower than that with full-spectrum input (91.67%), likely due to CARS over-optimizing certain bands and failing to preserve nonlinear characteristics. In contrast, ELM, by leveraging randomly initialized hidden-layer weights and non-linear activation functions, is inherently capable of modeling complex nonlinear relationships within spectral data [

46]. This characteristic, which allows for robust feature transformation and effective classification, likely contributed to its superior performance, achieving the highest OA and F1 among the traditional machine learning models tested.

3.5. Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models

Based on the data-level fusion strategy and the 1DCNN, the modeling results demonstrated that the synergistic effect of multi-dimensional information effectively enhanced the detection performance of external defects in seed potatoes, as shown in

Table 6.

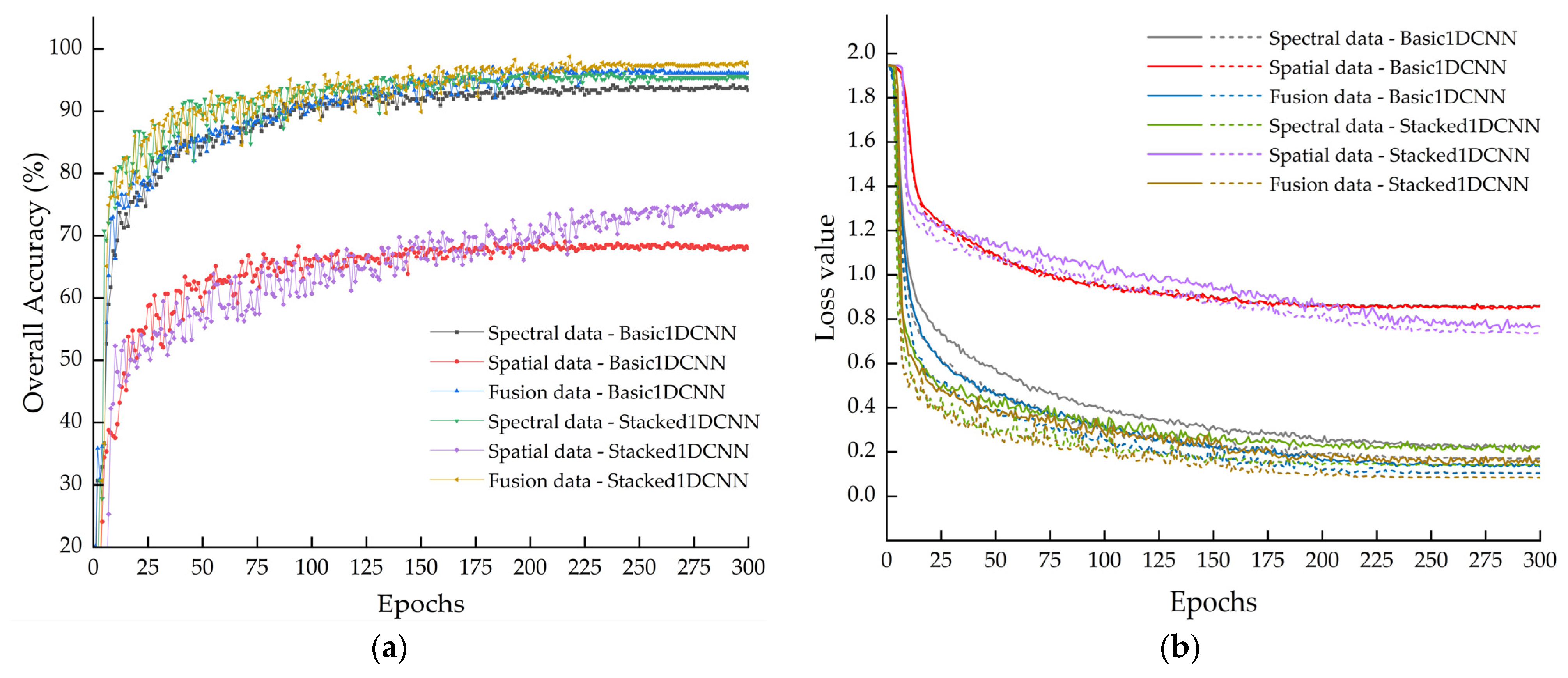

In the comparison using single spectral data, single spatial data, and fused spectral–spatial data as inputs, the fused dataset exhibited the best performance. Compared with the single spectral input, the Stacked1DCNN model with fused input achieved improvements of 2.81%, 2.78%, 3.20%, 3.01%, and 1.11% across the first five evaluation metrics. Similarly, the Basic1DCNN model showed corresponding increases of 3.13%, 2.88%, 3.25%, 3.22%, 1.86%. As illustrated in

Figure 9a, the validation set accuracy curve under fused input is generally higher than that under single input. Under the spectral input condition, the OA of the two models reached 94.10% and 96.07%, which were significantly higher than those obtained with spatial input alone (69.04% and 75.18%). Combined with spectral analysis, these results indicate that hyperspectral detection of external defects in seed potatoes primarily depends on their spectral response characteristics. Although image data provide some additional information complementary to the spectral data, relying on this alone is insufficient for accurate identification.

The Basic1DCNN model employs a single convolutional layer with a relatively small receptive field and introduces a dropout layer only at the output layer. In contrast, the Stacked1DCNN model is constructed using stacked dual-layer convolutional modules, with twice the number of channels as Basic1DCNN, thereby enhancing feature resolution and encoding capacity. A dropout layer is added at the end of each module to suppress overfitting and improve generalization. As illustrated in

Figure 9b, the loss value of Stacked1DCNN decreases more rapidly, indicating a stronger learning capability. Both models show no upward trend in validation loss and eventually converge. Further confirmation of their generalization capabilities and the absence of significant overfitting is provided by the highly performance metrics on the held-out validation set, as systematically presented in

Table 6. Under the fused input, Stacked1DCNN exhibited systematic improvements over Basic1DCNN, with OA, Pr, Re, F1, and mAP increased by 1.77%, 1.78%, 2.06%, 1.85%, and 0.62%, respectively.

The validation confusion matrices of Basic1DCNN and Stacked1DCNN under different input types are shown in

Figure 10. Overall, the Stacked1DCNN model exhibits higher recognition accuracy than Basic1DCNN. The fused input achieves the best performance across all categories, particularly by significantly reducing misclassifications between the easily confused categories of mechanical damage and wormholes. For example, in the Basic1DCNN, a total of 17 misclassifications occurred between the mechanical damage and wormhole categories under spectral input, which decreased to 9 under fused input. In the Stacked1DCNN, the corresponding misclassifications were 14 with spectral input and were significantly reduced to 3 with fused input.

In practical applications, the risk of missed detections (false negatives) is generally more critical than that of false alarms (false positives). As shown in

Figure 10, for the Basic1DCNN, 13 defective samples were misclassified as normal under spatial input, 1 under spectral input, and none under fused input (0 cases). Similarly, in the Stacked1DCNN model, 8 defective samples were misclassified as normal under spatial input, whereas no missed detections occurred under either spectral or fused input. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 11, the P–R curves of Stacked1DCNN demonstrate that the fused input achieves the best precision–recall performance, maintaining high precision at high recall levels and effectively balancing false negatives and false positives. From the area enclosed by the curves, the fused input exhibits the largest P-R curve area, followed by the spectral input, while the spatial input shows the smallest. These findings demonstrate that spectral–spatial fusion strategy effectively reduces the missed detection rate of defects, enhancing the robustness of defect detection and significantly improving the stability and reliability of the model.

Beyond performance, computational efficiency metrics such as training time and parameter count are also critical. As shown in

Table 6 compared to Basic1DCNN, Stacked1DCNN requires more parameters and longer training times across all input types. This architectural difference directly affects model performance. The higher parameter count of Stacked1DCNN enables it to learn more complex features, thereby improving accuracy. However, when the input information is limited, such as with spatial-only data, the benefit of additional parameters diminishes.

For Stacked1DCNN, the additional computational cost is justified, as it achieves higher OA and mAP in precise defect detection, which is particularly important for agricultural applications. As shown in

Table 4, compared to traditional machine learning models, deep learning models inherently require longer training times, due to their ability to automatically learn hierarchical features and their stronger feature extraction and generalization capabilities. In complex tasks, deep learning models clearly outperform traditional methods, demonstrating that extra computational investment is reasonable to achieve higher performance.

Ultimately, the Stacked1DCNN model using spectral–spatial fusion data provides the best balance for this application. Its high performance ensures robust defect detection, and although the computational demand is relatively higher, it remains manageable, with the resulting accuracy outweighing the computational cost.

3.6. Comparison with Recent Deep Learning-Based Methods

To further evaluate the proposed method in a broader research context, this section compares the experimental results of the present study with those reported in recent deep learning–based studies on potato defect detection and related agricultural products.

Table 7 summarizes the performance of different models across defect detection tasks involving potatoes and other agricultural products. The results indicate that, even with an increased number of defect categories, spectral–spatial fused data combined with the Stacked1DCNN model achieved higher detection accuracy than other models, demonstrating its accuracy advantage in seed potato defects detection. With further optimization and extension, the proposed approach also has the potential to provide a reference for the practical production inspection of similar agricultural seeds.

Despite differences in data acquisition conditions and defect types, such comparative analysis is still helpful for clarifying the positioning of the proposed spectral–spatial fusion method within current deep learning research. This study focuses on investigating the effectiveness of spectral–spatial data fusion under a controllable and interpretable 1D-CNN framework. For this study, considering the characteristics of the one-dimensional spectral–spatial input data and practical application requirements, Basic1DCNN and Stacked1DCNN were selected as representative shallow and deep 1D convolutional networks, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study adopts a data-level fusion strategy that integrates spectral responses related to chemical composition with the spatial texture information extracted from images, thereby effectively enhancing the defect recognition capability of seed potatoes. For example, frostbitten regions exhibit spectral reflectance characteristics similar to those of normal samples, whereas their surface wrinkles and spots present distinct texture patterns. As shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 10, spectral–spatial fused data achieved improved performance metrics and more favorable confusion matrices, providing quantitative evidence of the critical role of texture features. Notably, a misclassification by the Basic1DCNN model—where one normal sample was incorrectly identified as frostbite using spectral data alone—was corrected when fused data were used, directly demonstrating how spatial information helps resolve spectrally ambiguous defects.

The proposed Stacked1DCNN model with fused data input achieved an OA of 98.77%, surpassing the traditional machine learning method CARS-ELM, with other evaluation metrics also showing superior performance. This advantage stems from deep learning’s ability to automatically extract complex nonlinear features from full-spectrum hyperspectral data through multiple convolutional layers, by processing the fused spectral and spatial information to capture their deep correlations. Moreover, deep learning does not require manual feature design, enabling adaptive discovery of key patterns, strong robustness to noise and redundant information, and efficient training on large-scale datasets, thus allowing accurate recognition of complex defect types. In contrast, traditional machine learning relies on feature wavelengths selection, which, while reducing redundancy, may overlook potential nonlinear relationships, such as the effects of starch and protein degradation on spectral reflectance.

Although the proposed method demonstrates encouraging performance, it is worth noting that the dataset used in this study is relatively modest in size, primarily due to the cost and complexity of hyperspectral data acquisition and the need for careful manual annotation. As a result, the sample diversity may be somewhat constrained, which could influence the model’s generalization ability under more diverse real-world conditions. In addition, all experiments were conducted in a controlled laboratory environment. Future practical deployment would therefore benefit from further validation under varying operational conditions, such as changes in illumination, the presence of dust, and temperature fluctuations, which may affect hyperspectral data acquisition and model robustness. Future work will therefore focus on several aspects: (1) expanding the dataset by including more samples, different potato varieties, and commercial virus-free seed potatoes to further validate the robustness and applicability of the proposed approach under broader sample conditions; (2) conducting validation experiments in real production environments to assess the stability and reliability of hyperspectral imaging–based detection under different practical scenarios; and (3) incorporating attention mechanisms and other advanced deep learning techniques to enhance the model’s focus on key discriminative features and further improve overall robustness and detection performance. These efforts are expected to lay a more solid foundation for the practical application of hyperspectral imaging technology in seed potato defect detection and promote the continuous optimization and high-quality development of the potato industry.

5. Conclusions

This study focused on seed potatoes of the Zihuabai potato variety. Using a hyperspectral imaging system, one-dimensional spectral data within the 935–1721 nm range and two-dimensional image spatial data comprising 224 spectral bands were collected for both normal seed potatoes and six types of defect regions. By integrating multiple data processing methods, both traditional machine learning and deep learning classification models were constructed to achieve accurate identification of external defects in seed potatoes. The main conclusions are as follows:

Six preprocessing methods were compared for the original spectral data, and the OSC method was determined to be the most effective based on PLS-DA modeling, thus adopted for subsequent analysis. On this basis, SPA and CARS algorithms were employed to extract 37 and 30 feature wavelengths, respectively. For image spatial data, PCA was applied to extract the first three principal components, from which 24 texture parameters were derived from each component image using GLCM, resulting in a total of 72 texture features.

Using the preprocessed full-band spectra and the selected feature wavelengths as inputs, five traditional machine learning models were developed to classify normal and six defective regions. The results indicated that the CARS–ELM combination achieved the best performance, with an overall accuracy of 94.44%, precision of 94.62%, recall of 91.68%, and F1-score of 92.66%.

Using preprocessed spectral data, normalized spatial texture data, and their fusion data as inputs, two deep learning models were constructed: Basic1DCNN and an improved Stacked1DCNN. The results demonstrated that the Stacked1DCNN model with fused data input achieved the best overall performance, reaching an overall accuracy of 98.77%, precision of 98.77%, recall of 98.93%, F1-score of 98.73%, and mAP of 99.66%, outperforming the CARS–ELM traditional machine learning model.

In conclusion, the fusion of hyperspectral spectral and spatial data combined with Stacked1DCNN deep learning modeling enables highly effective detection of external defects in seed potatoes. This approach provides valuable insights for the development of automatic sorting and nondestructive detection equipment for seed potatoes.