1. Introduction

Winter jujube harvesting is a labor-intensive and seasonal operation that mainly relies on manual picking [

1]. However, with the aging population and rising labor costs, crop production costs continue to rise, and the market competitiveness of agricultural products is gradually declining. In order to reduce production costs and improve product competitiveness, robotic arm picking is becoming an important development trend in the field of winter jujube harvesting [

2].

Due to the unstructured nature of the fruit tree growth environment, which is full of complex obstacles such as branches and leaves, it is extremely challenging for robotic arms to pick fruits. In order to achieve efficient application of robotic arms in agricultural production, it is urgent to develop high-performance motion planning algorithms [

3]. The algorithm must prioritize safety, efficiency, and accuracy to ensure that the robot can complete the picking task stably and reliably.

In recent years, a large number of studies have been devoted to improving the adaptability and operating efficiency of agricultural robots in complex environments. For example, Fu et al. designed a kiwifruit multi-fruit cutting and picking robot that combines fruit growth characteristics and Monte Carlo-based workspace analysis to achieve efficient continuous picking [

4]. Pal et al. developed a visual system combining YOLOv5, DeepSORT, and LSTM to detect and track human activities in orchards in real time, thereby enhancing human–machine collaboration [

5]. Alaaudeen et al. proposed a fruit grasping vision system combining a lightweight single-stage detection network and instance segmentation, achieving an accuracy of more than 95% in various environments [

6]. Yu et al. proposed a lightweight winter jujube detection and counting method based on SOD-YOLOv5n and successfully deployed it in the Android application “JujubeDetector” for real-time fruit recognition and counting [

7]. In addition, accurate camera calibration, object recognition, and obstacle detection are crucial to improving harvesting efficiency [

8,

9].

Despite great progress in information perception and target recognition technologies, intelligent fruit picking still faces huge challenges. Obstacle avoidance in path planning is one of the core technologies that aims to achieve fast and high-quality picking while ensuring operational safety and efficiency. Mainstream path planning methods can be roughly divided into graph-based methods, sampling-based methods, and deep reinforcement learning methods.

Graph-based algorithms (A*, Dijkstra, Floyd–Warshall) build a complete graph structure for path search, which is very suitable for static or low-dimensional dynamic environments and can generate complete paths. However, these methods usually suffer from poor smoothness and path continuity problems, are not suitable for robotic arm control, and their performance degrades significantly in high-dimensional spaces [

10,

11,

12].

Deep reinforcement learning combines neural networks with reinforcement learning, enabling robotic arms to autonomously plan paths in unknown environments through trial and error [

13,

14]. These methods are highly adaptable to dynamic, high-dimensional, and complex tasks. However, they typically require large amounts of training data, have slow convergence, and have limited generalization capabilities, making practical deployment challenging.

Sampling-based algorithms (e.g., RRT, RRT*, PRM) plan paths by randomly sampling in continuous space. These methods have good scalability in high-dimensional environments and are suitable for dynamic or complex scenes. Although their initial paths may lack quality, post-processing can significantly improve the smoothness and feasibility of the paths [

15,

16,

17].

As a sampling-based algorithm, RRT is widely used in robot path planning because of its powerful high-dimensional search capability. However, the algorithm has problems such as a non-smooth path, low search efficiency, and an inability to guarantee optimality, which leads to unsatisfactory execution results in complex scenarios [

18]. To address these problems, the BI-RRT (bidirectional RRT) algorithm was proposed, which constructs a search tree from the starting point and the target point and alternately expands the search tree to improve efficiency [

19,

20]. However, the algorithm still has limitations in terms of direction guidance, step size control, and expansion efficiency, and it is difficult to meet the changing needs of dynamic and complex environments.

To overcome these challenges, several enhancement algorithms have been developed. For example, Wang et al. proposed AEB-RRT*, which combines a Manhattan distance-based guidance strategy to improve extension directionality [

21]. Liao et al. introduced F-RRT*, which uses the triangle inequality to optimize parent node selection to accelerate convergence [

22]. Liu et al. used Bezier curves in bidirectional RRT to enhance path smoothness [

23]. However, these methods still lack sufficient adaptability in non-regular or dynamic environments.

In practical deployment, real-time collision detection remains a major bottleneck in improving path planning efficiency. Traditional point-by-point collision checks are inefficient in dense obstacle environments, failing to meet real-time demands. To address this, Bounding Volume Hierarchies (BVH) have been widely adopted to build hierarchical spatial structures [

24]. However, single-level BVH structures struggle to balance accuracy and efficiency when dealing with uneven obstacle distributions. For instance, Cao et al. integrated LeGO-LOAM, traversability analysis [

25], and RRT* into an orchard navigation system that adapts to dynamic environments, though real-time performance remains limited. Yu et al. proposed RDT-RRT, which combines CNN-based collision detection with spline-based path smoothing to improve trajectory quality [

26], but its high computational load restricts deployment in resource-constrained systems.

Moreover, paths generated by many RRT-based algorithms exhibit jagged turns and lack smoothness due to discrete sampling and linear connections, falling short of the motion continuity and gentleness required by agricultural robotic arms. Although optimization mechanisms have been introduced in variants like Informed-RRT* [

27], CBERRT* [

28], and Smooth-RRT* [

29], path quality still degrades in densely obstructed or highly dynamic orchard environments.

To tackle these challenges, this study proposes a novel path planning algorithm—BMGA-RRT Connect (BVH-based Multilevel-step Gradient-descent Adaptive RRT Connect). The algorithm incorporates three key innovations: (1) an adaptive multilevel step-size strategy to improve node expansion flexibility; (2) a hierarchical BVH-based collision detection mechanism to enhance computational efficiency; (3) a gradient descent-based path optimization module to generate smooth and continuous high-quality paths.

Building upon the global search capabilities of traditional sampling algorithms, BMGA-RRT Connect significantly improves path quality and execution feasibility. It is particularly well-suited to complex, obstacle-dense agricultural environments such as orchards, showing promising application potential.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

The algorithm is capable of generating shorter and smoother paths while significantly reducing the standard deviation of both path length and computation time.

- (2)

In dynamic environments, the algorithm achieved a planning success rate of over 90% in both 2D and 3D simulations. Field experiments in jujube harvesting further validated its effectiveness, with a 100% planning success rate and a 90% task execution rate.

- (3)

BMGA-RRT Connect adopts a lightweight, modular architecture that supports rapid BVH updates for moving obstacles, requires only minimal parameter tuning to transfer across different manipulators and crop scenarios, and maintains a low computational footprint suitable for on-board deployment in resource-constrained agricultural robots.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kinematic Model of the Robotic Arm

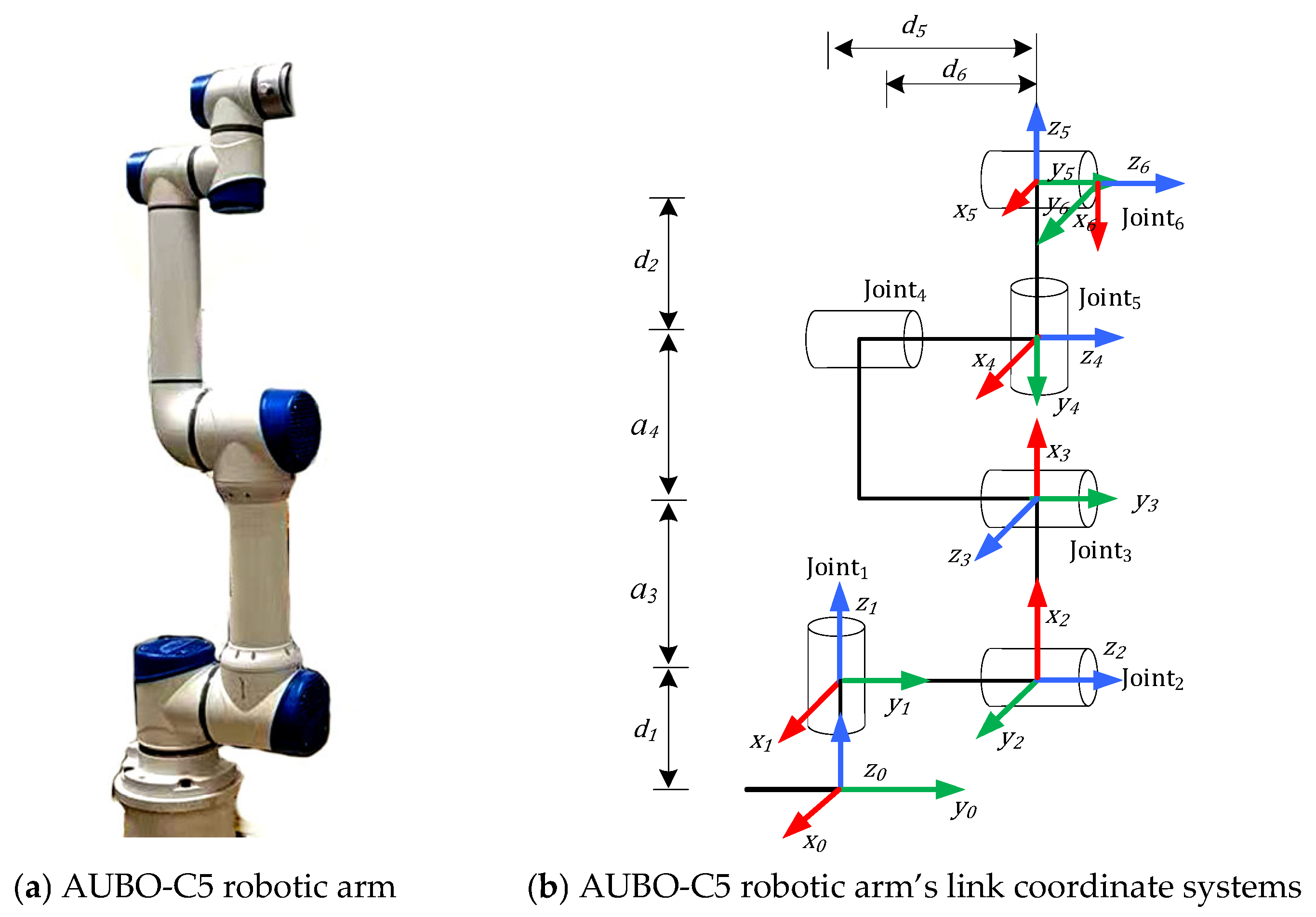

Figure 1 illustrates the prototype system of the winter jujube harvesting device developed in this study. The system primarily consists of a robotic arm(AUBO-C5, Hangzhou, China), control box (Hangzhou, China), depth camera, computer(HP Spectre x360 9, Huizhou, China), winter jujube tree (Hangzhou, China), and end-effector (Hangzhou, China).

As shown in

Figure 1, an Intel RealSense D435i depth camera (Intel, Chandler, AZ, USA) is employed for obstacle detection and to acquire point cloud data from the working environment. Due to the large volume of three-dimensional information contained in point cloud data, they require significant storage and computational resources, making them unsuitable for direct environmental modeling. To address this, the octree method is used to process and map the point cloud data, facilitating the construction of an octree map for efficient environmental representation.

In this study, the update frequency of the depth camera was set to 2.5 Hz to ensure real-time environmental perception while optimizing computational resource usage. The camera’s maximum reading depth was set to 1.5 m, with a resolution of 1.5 cm. This resolution means that the smallest voxel in the octree map has an edge length of 1.5 cm. While a higher update frequency provides more detailed environmental awareness, it also increases the computational load. Conversely, a frequency that is too low could result in delayed responses to environmental changes.

Figure 2a shows the three-dimensional structural model of the winter jujube harvesting device. The robotic arm used in this study is the AUBO-C5 model, which features revolute joints. The sixth joint connects to the end-effector, which serves as the winter jujube harvesting tool. The coordinate system of the robotic arm was established using the Denavit–Hartenberg (DH) parameter method.

As shown in

Figure 2b, the specific connection parameters for each joint are provided in

Table 1. Joints 1, 2, and 3 are primarily responsible for the arm’s positioning, while joints 4, 5, and 6 control the orientation of the end-effector in three-dimensional space.

2.2. RRT Connect Algorithm

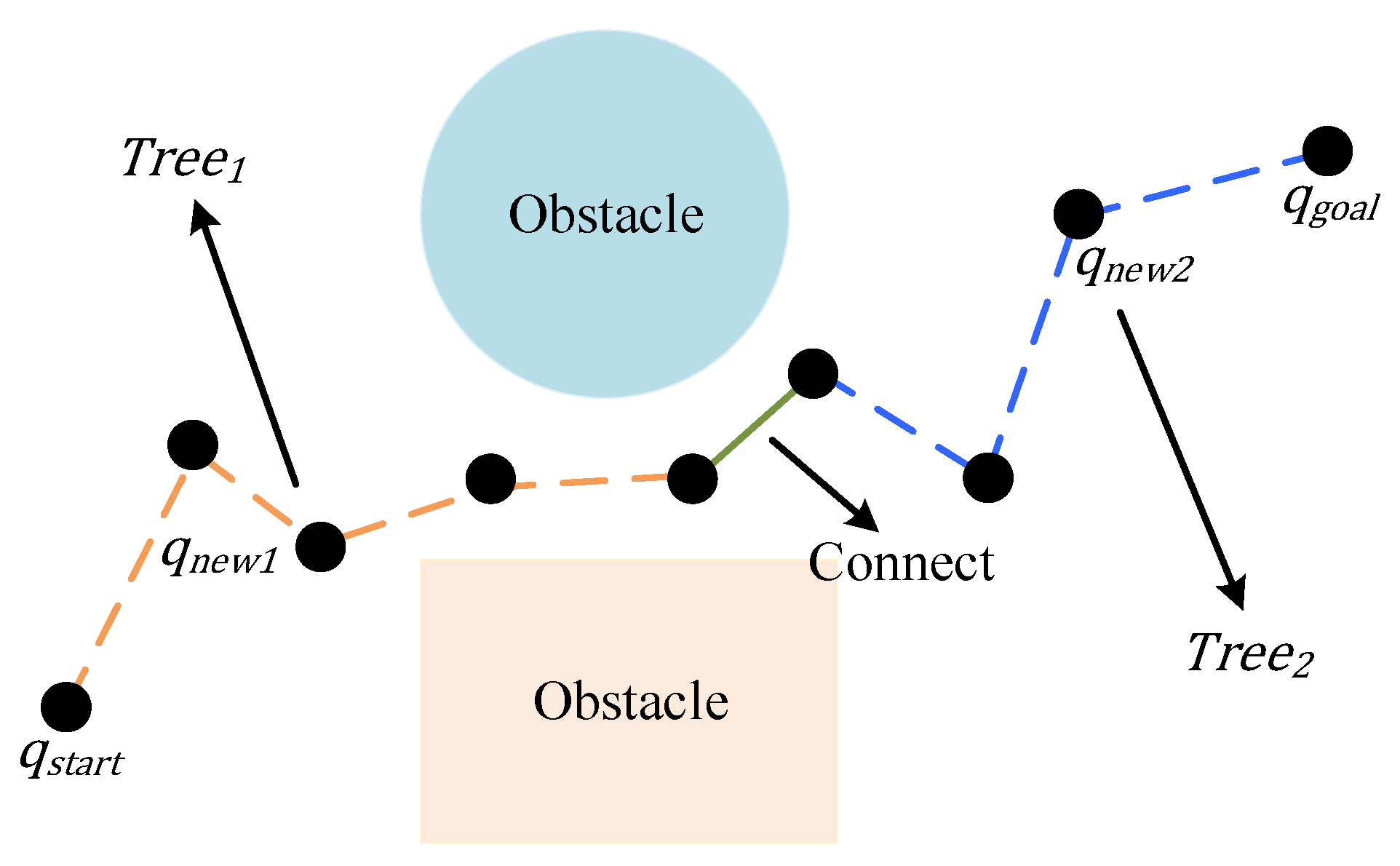

The RRT Connect algorithm is a path planning method built on the RRT framework. Its core idea involves constructing two random trees, one rooted at the start point and the other at the goal point and alternately expanding each tree toward the other within the search space. To enhance search efficiency, the algorithm integrates a greedy strategy that accelerates both path generation and connection. The node expansion process within the random tree is described as follows:

Step 1: Determine the start point and the goal point of the path. Construct two random trees rooted at these points within the search space, and generate a random sampling point .

Step 2: Traverse the random tree to find the tree node that is closest to the sampling point . Expand the tree by a step size toward to obtain a new node . Check whether the line segment and intersects with any obstacles. If no obstacles are detected, add to ; otherwise, discard and resample.

Step 3: Traverse the random tree to find the tree node that is closest to the new node . Expand the tree by a step size toward to obtain a new node . Check whether the line segment between and intersects with any obstacles. If no obstacles are detected, add to the and apply the greedy strategy to continue expanding in the direction of , stopping when an obstacle is encountered or the distance between the closest points of the two trees is smaller than a predefined threshold. If an obstacle is detected, discard .

Step 4: Repeat Steps 2 and 3 to alternately expand the two random trees. When the distance between the nearest nodes of the two trees becomes smaller than a predefined threshold, connect the two trees to generate a valid path from the start point to the goal point. Return the relevant node information to complete the path search process.

The schematic diagram is shown in

Figure 3.

2.3. BMGA-RRT Connect Algorithm

The BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm is an improved path planning method proposed based on the RRT-Connect algorithm. Although the traditional RRT-Connect algorithm performs well in terms of planning speed, it still faces issues in practical applications, such as low search efficiency, long collision detection times, and poor path smoothness. To address these shortcomings, this study introduces the BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm, with three key innovations:

Firstly, an adaptive multilevel candidate step-size strategy is introduced to optimize the node expansion process and improve search efficiency. Secondly, a multilevel collision detection technique based on BVH is employed, which effectively reduces the computational overhead of collision detection. Finally, a post-processing optimization is applied to the initially generated path using a gradient descent method to enhance path continuity and smoothness, resulting in an efficient and smooth trajectory.

The base step size and adaptive step-size thresholds were selected according to the scale of the robot workspace, obstacle density, and kinematic constraints of the robotic manipulator, and were refined through preliminary testing to balance exploration efficiency and collision avoidance. The weighting coefficients in the path smoothing cost function were determined based on the relative importance of path length minimization, trajectory smoothness, and collision clearance, following commonly adopted practices in motion planning.

2.3.1. Adaptive Multilevel Candidate Step Size

In the traditional RRT-Connect algorithm, a fixed step size is typically used for node expansion. However, due to the complexity of real-world environments, this strategy may lead to inefficiency or excessive node expansion. For example, in narrow spaces, a large step size may result in frequent collision detection failures, while in open spaces, a small step size reduces search efficiency and increases computational overhead. To address this issue, the BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm introduces an adaptive multilevel candidate step-size strategy, which dynamically adjusts the step size based on real-time environmental changes, improving both the efficiency and quality of path planning.

The core idea of the adaptive step size is to adjust the step size dynamically based on local environmental features during the node expansion process. Specifically, when obstacles are dense or the environment is complex, the step size is reduced for finer expansion; in open areas, the step size is increased to accelerate the search process.

In the implementation process, we define obstacle distance thresholds

and

, and dynamically adjust the step size

based on the distance

between the node expansion position and the nearest obstacle distance

As shown in Equation (1):

The candidate step-size set

is defined As shown in Equations (2)–(4):

In this context,

is the predefined base step size.

is a larger candidate step size used in open environments.

represents a moderate step size applied in areas with intermediate complexity.

is a smaller step size, mainly used in regions with dense obstacles or when approaching the target point. As illustrated in

Figure 4.

The pseudocode of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1: Adaptive Multilevel Candidate Step Algorithm. |

Input: , , , , - 1:

← ComputeObstacleDistance; - 2:

if ≥ then - 3:

← [2.0×, 1.8×, 1.6×]; - 4:

else if ≤ < then - 5:

← [1.2×, 1.0×, 0.8×]; - 6:

else - 7:

← [0.6×, 0.4×, 0.2×]; - 8:

for each in - 9:

← Extend(, , ); - 10:

If CollisionFree(, ) then - 11:

return ; - 12:

return null;

|

2.3.2. Multi-Stage Collision Detection Based on BVH

In complex virtual environments, the real-time performance and accuracy of collision detection are of great importance in fields such as simulation, gaming, and robotic motion planning. Traditional point-by-point detection methods become inefficient when dealing with large-scale scenes. As a result, multilevel collision detection methods based on BVH have emerged as one of the mainstream solutions.

The core idea of BVH is to encapsulate objects using simple geometric bounding volumes in a hierarchical manner, allowing the detection process to proceed from coarse to fine levels. When checking for collisions between two objects, the algorithm first performs a fast screening using high-level bounding volumes and only proceeds to more detailed checks for regions that are likely to collide. This hierarchical approach reduces unnecessary computations and significantly improves detection efficiency.

The multilevel collision detection method based on BVH consists of two main stages:

- (1)

Broad-phase Collision Detection

This phase uses the Axis-Aligned Bounding Box (AABB) method to quickly eliminate regions that are unlikely to result in collisions, thereby significantly reducing the computational load required for fine-grained detection.

- (2)

Narrow-phase Collision Detection

In this phase, objects preliminarily identified as potentially colliding are recursively examined along the BVH tree structure. Each child node is checked step by step for possible collisions. At the lowest level (leaf nodes), precise collision checks are performed on the actual geometric models, such as computing intersections between triangle meshes or convex polygons. The schematic diagram is shown in

Figure 5.

The pseudocode of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 2:

| Algorithm 2: BVH-based Multi-Stage Collision Detection. |

Input: , - 1:

if NOT Intersect(, ) then - 2:

return false; - 3:

end if - 4:

if is leaf and is leaf then - 5:

return PreciseCollisionCheck(, ); - 6:

else if is leaf and is not leaf then - 7:

for each child node in do - 8:

if BVHCollisionDetection(, ) then - 9:

return true; - 10:

end if - 11:

end for - 12:

else if is leaf and is not leaf then - 13:

for each child node in do - 14:

if BVHCollisionDetection(, ) then - 15:

return true; - 16:

end if - 17:

end for - 18:

else - 19:

for each child node in do - 20:

for each child node in do - 21:

if BVHCollisionDetection(, ) then - 22:

return true; - 23:

end if - 24:

end for - 25:

end for - 26:

end if - 27:

return false;

|

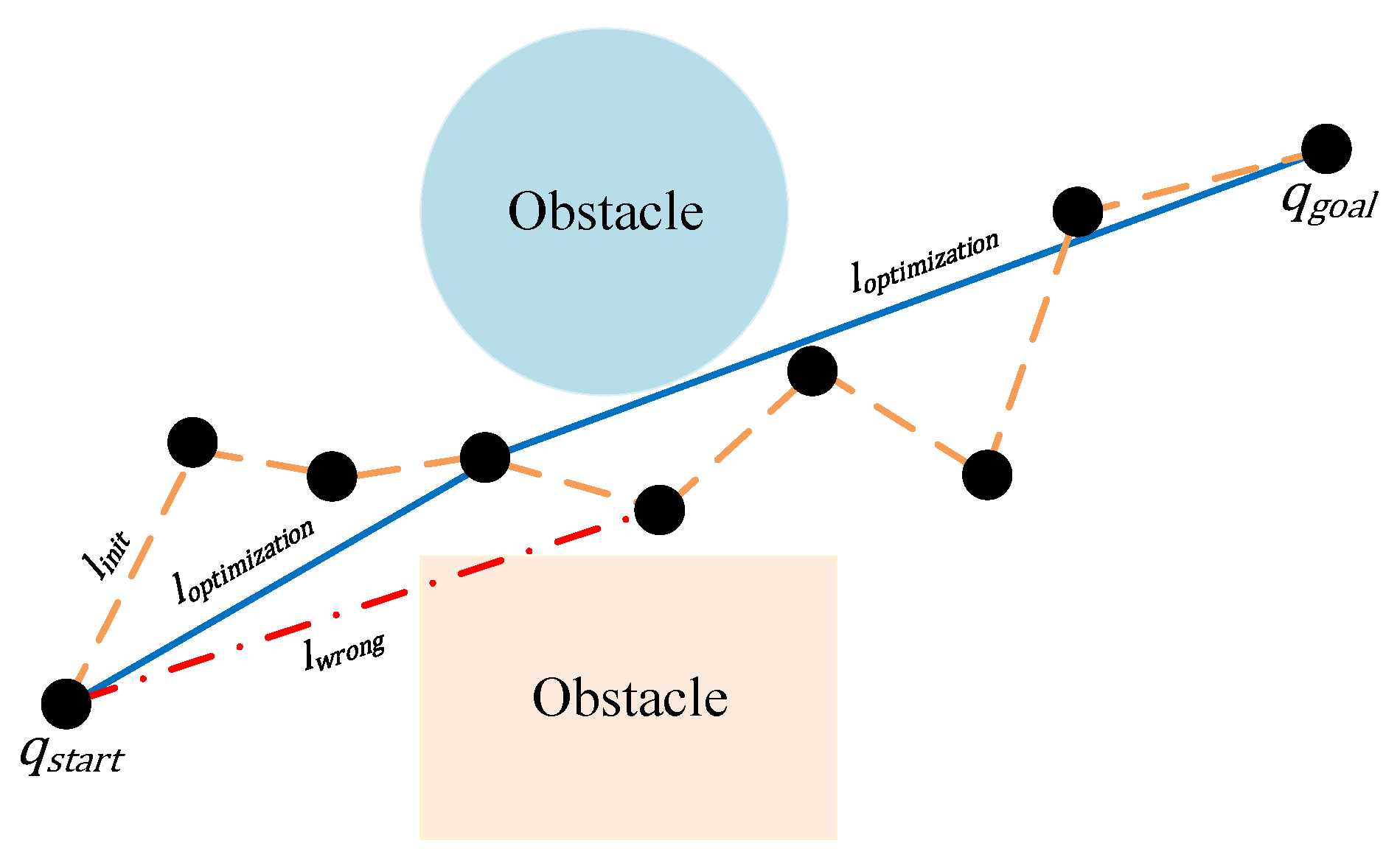

2.3.3. Gradient Descent Path Smoothing

In the process of robotic path planning, the initial path generated by rapid search algorithms often contains redundant points and irregular turns. These issues not only increase the overall path length but also reduce the smoothness of the robot’s motion. To improve path quality, this study applies a gradient descent method for path smoothing.

The approach formulates a cost function by treating the positions of the path points as optimization variables and iteratively adjusting them using the gradient information of the cost function. Through this process, the path gradually becomes smoother and more optimal. This method effectively reduces sharp turns and redundant points along the path, thereby improving the fluency and executability of robotic motion.

The cost function for path smoothing based on gradient descent is defined as Equations (5)–(8):

where

is the path smoothness term, which reflects the curvature or turning degree of the path,

is the path length term, used to control the total path length and reduce redundancy.

is the obstacle constraint term, which prevents path points from approaching or passing through obstacles.

,

,

are weighting coefficients that control the relative importance of each term during optimization.

denotes the position of the

point on the path.

represents the distance from point

to the nearest obstacle. The schematic diagram is shown in

Figure 6.

The pseudocode of the algorithm is shown in Algorithm 3:

| Algorithm 3: Gradient Descent PathSmoothing Algorithm. |

Input: Initial path , parameters , , , Maxlterations

- 1:

for to Maxlterations do - 2:

for each intermediate path point , do - 3:

Compute gradient ∇; - 4:

Update path point: - 5:

←∇; - 6:

end for - 7:

if convergence criteria met then - 8:

break; - 9:

end if - 10:

end for - 11:

return smoothed path ;

|

3. Results

To evaluate the effectiveness of the motion planning for the winter jujube harvesting device, this study conducted two-dimensional simulation experiments, three-dimensional simulation experiments, and physical grasping experiments to verify the performance of the proposed BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm.

3.1. Experimental Setup

In this section, the performance of five path planning algorithms—RRT, RRT Connect, RRT*, Informed-RRT*, and BMGA-RRT Connect—is evaluated and compared. Experiments were carried out in two distinct environments, referred to as the single jujube fruit environment and the multiple jujube fruit environment. All experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel® Core™ i7-13620H CPU and 32 GB of RAM. All algorithms were implemented using Python 3.12.

All algorithms were evaluated using identical iteration limits to ensure a fair comparison under practical real-time harvesting constraints. All experiments also used the same SOD-YOLOv5n-based detection results to eliminate the influence of perception variability.

3.2. The 2D Simulation Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of the path planning algorithms, a simulated environment of 100 × 100 units was constructed, with the origin (0, 0) placed at the bottom-left corner. The start and goal points were located at (0, 0) and (90, 90), respectively, and were marked with blue and green. Obstacles were represented by enclosed gray polygons scattered across the map. The blue trajectory illustrates the search path explored by the algorithm from the start point towards the goal, while the red path indicates the final optimized trajectory after post-processing.

Each algorithm was executed for 1000 iterations, with a 10% probability of selecting the goal point as the sampling target. A fixed step size of 1 unit was applied. To ensure statistical reliability, 20 independent test runs were performed for each algorithm. The results of these experiments are summarized in

Figure 7.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the four algorithms, this study selected average path planning time and path length as key metrics. In addition, a composite score was introduced to jointly assess planning efficiency and path quality. To further evaluate the stability and efficiency of the algorithms, standard deviation analysis was also conducted.

Stability was measured based on the standard deviations of path length and planning time. A smaller standard deviation indicates that the algorithm performs more consistently under varying test conditions. Efficiency was evaluated using path length and planning time, where shorter paths and faster planning times indicate higher computational efficiency.

The final evaluation objectives of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

A smaller standard deviation results in a higher score, reflecting better algorithmic stability;

- (2)

Shorter path length and shorter planning time lead to higher scores, indicating greater computational efficiency;

- (3)

The scoring system distinguishes between different algorithms and ensures that the composite score effectively reflects the overall performance.

Accordingly, the formula for the composite score is defined in Equation (9).

To highlight the importance of path length and planning time in the optimization process, this research assigns a weight of 0.15 to and . In comparison, the weights for the planning success rate and execution success rate are set to 0.35, ensuring that the score more accurately reflects the algorithm’s overall effectiveness and efficiency in practical applications.

The results recorded from the experiments are summarized in

Table 2, as shown below:

According to the data in

Table 2, the five path planning algorithms exhibit significant performance differences in two-dimensional space. In terms of computation time, BMGA-RRT Connect achieved an average of 2.23 s, significantly faster than RRT (6.88 s) and RRT Connect (3.43 s), demonstrating superior computational efficiency. Although the average path length of BMGA-RRT Connect was 139.90 mm, it achieved an 11.85% reduction compared to RRT Connect, indicating strong path optimization capabilities.

In terms of path stability, the standard deviation of the path length for BMGA-RRT Connect is 3.06 mm, the smallest among the five algorithms, showing its higher consistency and stability. In terms of planning success rate, both BMGA-RRT Connect and Informed-RRT* achieved 100%, significantly higher than RRT’s 75%. Furthermore, the standard deviation of computation time for BMGA-RRT Connect is only 1.28 s, demonstrating excellent time consistency.

Considering all evaluation metrics, BMGA-RRT Connect ranks first with a score of 81.48, showcasing its overall advantage in computational efficiency, path optimization, and stability. Overall, BMGA-RRT Connect performs exceptionally well in the 2D environment, making it particularly suitable for path planning tasks that require high real-time performance and stability.

3.3. The 3D Simulation Experiments

To evaluate the performance of the algorithms, a simulated three-dimensional environment measuring 100 units per side was constructed, with the origin (0, 0, 0) at the bottom-left corner. The start point was located at (0, 0, 0) and the goal point at (90, 90, 90), denoted in blue and green, respectively. Obstacles were represented by enclosed gray shapes scattered across the map, which needed to be avoided during path planning. The blue trajectory represents the search path explored by the algorithm from the start to the goal, while the green trajectory shows the search path from the goal to the start. The final optimized path was shown in red. The constructed 3D environment is illustrated in

Figure 8.

To evaluate the performance of BMGA-RRT Connect in comparison with other path planning algorithms, a set of experiments was conducted under identical obstacle conditions. The evaluated algorithms included RRT, RRT*, RRT Connect, Informed-RRT*, and BMGA-RRT Connect. The robotic arm was required to perform the same task in each case, moving from a fixed start point to a goal point. Each algorithm was tested 20 times.

During the experiments, the planning time and path length for each trial were recorded, and the average values were calculated. To comprehensively assess the performance of the five algorithms, the same evaluation metrics used in the 2D simulation experiments were applied, including average planning time, average path length, and planning success rate. The recorded results were summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3 summarizes the comparative performance of five path planning algorithms evaluated in 3D space, providing clear insights into their computational efficiency and optimization capabilities. Among these methods, BMGA-RRT Connect exhibits superior overall performance, achieving the highest composite score of 90.41. Notably, it also records the shortest average computation time (7.12 s), significantly lower than those of the other four algorithms: RRT (14.60 s), RRT* (30.44 s), RRT Connect (12.98 s), and Informed-RRT* (28.37 s).

In terms of path optimization, BMGA-RRT Connect achieves an average path length of 166.81 mm, representing improvements of 12.71% compared to RRT (191.10 mm) and 20.24% compared to RRT Connect (209.16 mm) Furthermore, BMGA-RRT Connect exhibits outstanding stability, reducing the standard deviation of path length to 4.06 mm and computation time to 1.68 s—markedly lower than other algorithms, thus underscoring its consistency in performance.

In terms of planning success rates, BMGA-RRT Connect, RRT*, and Informed-RRT* achieve perfect success rates (100%), surpassing RRT (85%) and RRT Connect (90%). These findings further underscore BMGA-RRT Connect’s superior performance, demonstrating an optimal balance across computational efficiency, path optimization, algorithm stability, and planning reliability within complex 3D environments.

3.4. Dynamic Map Validation Experiment

Considering that the robotic arm may be affected by wind-blown branches during the harvesting process, creating dynamic obstacles, experiments were conducted to validate the performance of the BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm in dynamic environments. The algorithm parameters remained consistent with those used in the aforementioned 2D and 3D environments. Unlike static obstacle environments, dynamic obstacles were set to move randomly within a specified range at a constant speed. The movement range of the obstacles was set to [−1, 1], simulating the variation in dynamic obstacles. The map was updated every 200 iterations. The results of the 2D algorithm validation experiment are shown in

Figure 9.

In the 3D environment, the map is updated every 200 iterations. The results of the 3D algorithm validation experiment are shown in

Figure 10According to the data in

Table 4 and the results shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the performance of BMGA-RRT Connect in the dynamic map validation experiments differs between the 2D and 3D environments.

In the 2D environment, BMGA-RRT Connect achieved excellent computational efficiency, with an average computation time of 2.86 s and an average path length of 142.75 mm. Additionally, the algorithm exhibited strong stability, demonstrated by a path length standard deviation of only 4.17 mm and a computation time standard deviation of 1.42 s. Notably, BMGA-RRT Connect maintained a perfect planning success rate (100%), highlighting its robust performance and consistent reliability. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the paths produced by the algorithm showed minimal variance, underscoring its effectiveness and stability in two-dimensional scenarios.

In comparison, when applied to the more complex 3D environment, BMGA-RRT Connect experienced a noticeable reduction in computational performance. Specifically, the average computation time increased to 7.84 s, reflecting a 174.13% increase relative to the 2D environment, and the average path length extended to 167.84 mm, an increase of 17.57%. Moreover, the planning success rate declined to 90%, which can primarily be attributed to the increased complexity of obstacles and spatial configurations in the 3D space, as shown in

Figure 10. Nevertheless, BMGA-RRT Connect still maintained stable and reliable overall performance, successfully balancing computational efficiency and path optimization even under more challenging conditions.

3.5. Winter Jujube Picking Experiments

In this study, path planning for the AUBO-C5 robotic arm was implemented using Python and ROS. The BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm was deployed and tested in the MoveIt! Framework.

To evaluate the performance of the BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm in picking tasks, laboratory experiments were conducted in conjunction with a vision-based localization system. A depth camera was used to capture the position of the targets and obstacles, and the environment was modeled using the octree method. The point cloud data were converted into octree format and integrated into the ROS system. The BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm was then applied to generate a discrete picking path sequence for the robotic manipulator.

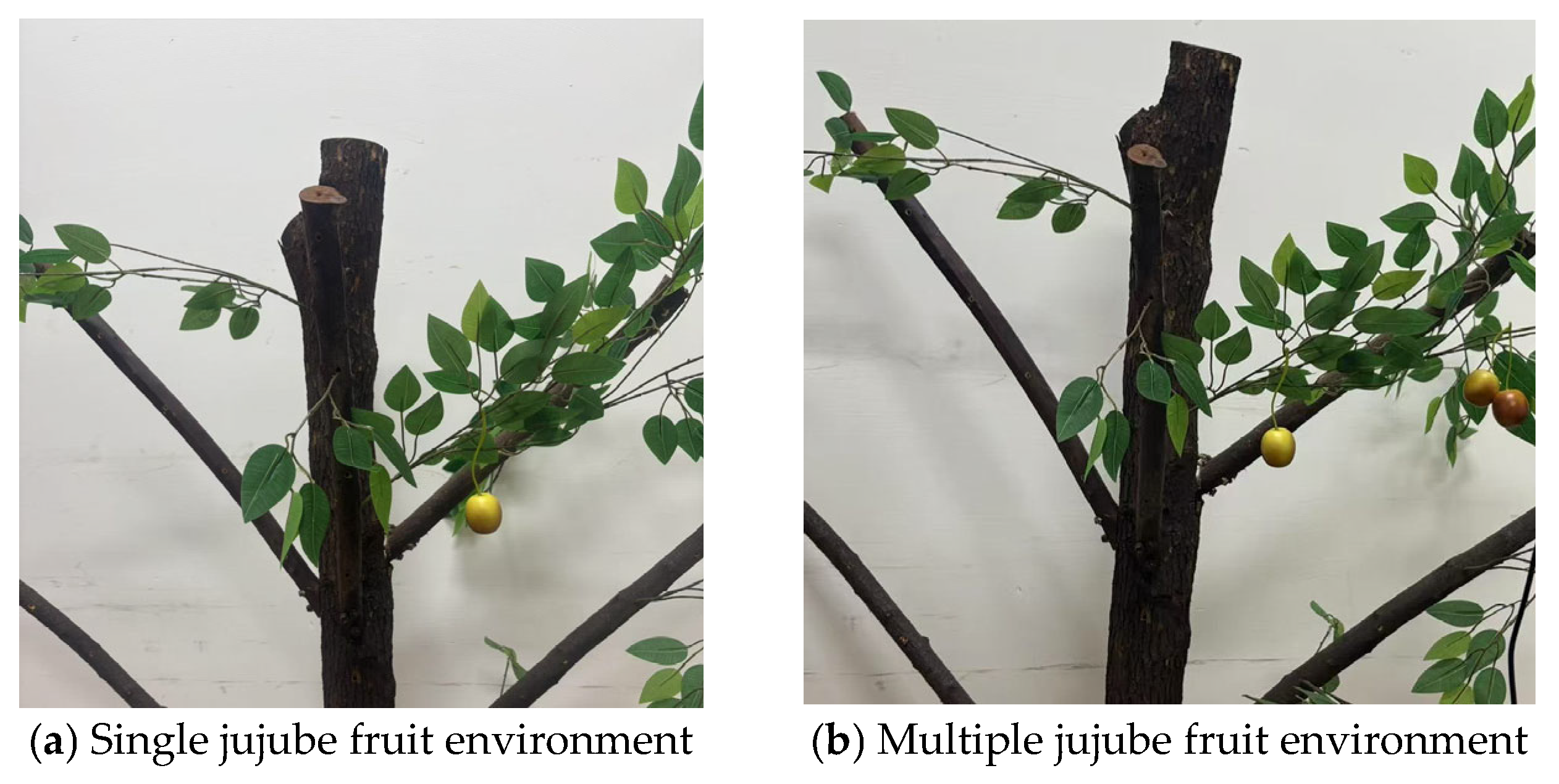

The experiments were conducted in two typical environments to validate the algorithm’s adaptability and robustness under different levels of complexity. Single jujube fruit environment consists of a small sapling with soft branches and sparse leaves, on which a simulated fruit is surrounded by branches. The multiple jujube fruit environment is more complex, featuring dense foliage and multiple simulated fruits, each surrounded by branches. As shown in

Figure 11:

During the experiment, after the robot was manually positioned, the vision system detected the fruits and obstacles and planned a collision-free path for each fruit. The end-effector then followed the planned path to approach the position of each fruit and performed the grasping operation, as shown in

Figure 12.

The number of fruits harvested in each trial was determined based on the number of fruits detected by the vision system. A stopwatch was used during the experiment to record the entire harvesting process, including the number of detected fruits, the number of path planning attempts, the planning time, and the execution time. After the tests were completed, the planning success rate, execution success rate, average planning time, and average execution time were calculated based on the collected data. The recorded results are summarized in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

In the jujube harvesting experiments, BMGA-RRT Connect outperformed the baseline algorithms overall. In both single-fruit and multi-fruit environments, its average planning times were 0.35 s and 1.14 s, respectively, which were notably faster than those of RRT and RRT Connect. This indicates that the proposed method has greater advantages in response speed, mainly because it integrates bidirectional search with an improved heuristic strategy during the expansion process, thereby reducing redundant sampling.

In terms of task completion, BMGA-RRT Connect achieved a 100% planning success rate and a 90% execution success rate, both higher than traditional RRT and RRT*. These results show that the generated paths are not only computationally feasible but can also be executed stably, demonstrating strong reliability. Although this study did not directly compare with existing research on winter jujube harvesting, the four baseline algorithms selected are representative methods in the field of path planning and thus provide a solid benchmark for validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Most existing studies on winter jujube harvesting focus on improved versions of RRT or RRT*, which still face challenges such as longer computation times and lower execution success rates in environments with complex branch structures and multiple fruits. The experimental results of this study demonstrate that BMGA-RRT Connect performs better in these aspects, indicating that it can compensate for some of the limitations of current methods.

From a practical perspective, fruit-harvesting robots often encounter difficulties such as intertwined branches and densely distributed fruits, where the speed and stability of path planning directly determine their operational efficiency. The results of this study confirm that the proposed method can effectively address these challenges, making it a promising solution not only for winter jujube harvesting but also for the automation of other fruit crops.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed the BMGA-RRT Connect algorithm to tackle the problem of path planning for robotic harvesting in complex orchard environments. The algorithm combines adaptive step size adjustment, hierarchical collision checking, and path smoothing to improve efficiency and stability. Experiments carried out in both simulation and field settings showed that the method can produce shorter and smoother paths, which help the robotic arm move more consistently and with better repeatability.

Compared with classical RRT-based methods, which often face difficulties when fruit is densely distributed or when branches are highly intertwined, BMGA-RRT Connect achieved faster planning times and higher execution success rates. These improvements suggest that the approach has advantages not only in computation but also in practical operation, and it may provide a more suitable option for robots working in semi-structured orchards.

At the same time, this work still has limitations. The experiments were carried out in relatively limited scenarios, and the performance has not yet been tested on a large scale or under very diverse tree structures. In addition, the results were not supported by extensive statistical analysis due to data constraints.

It should be noted that the proposed method was evaluated under relatively controlled and homogeneous experimental conditions. Environmental factors such as illumination changes, glare, dust, fog, or rain were not explicitly considered and may affect perception robustness and overall system performance.

Future work will therefore focus on broadening the range of experimental conditions, incorporating real-time perception and sensor fusion, and applying the method to other crops. These directions could further strengthen adaptability and robustness, helping to move agricultural robotics closer to reliable deployment in real farming environments.