1. Introduction

Sugarcane, a type of perennial grass belonging to the poaceae family, is mainly grown in tropical and subtropical climates and plays a crucial economic role in numerous nations and regions [

1]. Its high sugar concentration makes it a key ingredient in sugar manufacturing. Moreover, the byproduct known as bagasse, produced during the sugar extraction process, can be utilized to create various products, including paper, fiberboard, and animal feed, showcasing its versatile uses [

2,

3]. China ranks as the third-largest producer of sugarcane worldwide, with a significant need for mechanized farming methods [

4,

5,

6]. However, while mechanical harvesting enhances efficiency, it has also resulted in a notable increase in impurity levels. These impurities significantly impact both the sugar yield and the economic returns of sugar production [

7,

8]. Additionally, they can shorten the lifespan of processing equipment, raise production expenses, and diminish the sugar output from the primary crop [

9]. At present, sugar mills continue to depend on manual methods for identifying impurities in the harvested sugarcane, which leads to challenges such as inefficiency, high rates of error, and a lack of scientific rigor, creating conflicts among sugar mills, harvesting crews, and sugarcane growers [

10].

To address this inconsistency, researchers typically employ image processing or machine vision techniques for detection across different phases [

11,

12,

13]. However, the use of supplementary devices is crucial to improve the effectiveness and precision of impurity identification [

14,

15,

16,

17]. For example, Zheng [

18] carried out detection during the harvesting phase by creating an experimental setup that mimics the placement of the detection apparatus at the discharge point of a segmented sugarcane harvester. Detection takes place as sugarcane descends from the discharge area, where experimental data is gathered and compared against the actual impurity levels to confirm the detection outcomes. This approach may be influenced by the considerable dust present within the harvester during real harvesting, potentially affecting the detection accuracy. Conversely, Zheng [

19] also conducted detection during the entry processing phase, designing a lifting and transport mechanism to assess the impurity rate in sugarcane. This apparatus features an image capture system that photographs sugarcane on the drum assembly, while the lifting mechanism continuously raises the transported sugarcane to the imaging zone. The objective is to determine the proportion of the area occupied by impurities in each image frame, compute the average ratio over time to create a temporal variation curve, and then align this curve with a standard reference. If the overlap degree is less than or equal to the standard threshold, the impurity rate is classified as high; otherwise, it is considered acceptable. This technique may face challenges due to stacking during the lifting process, which can diminish the image area ratio and result in an underestimation of detection outcomes. To tackle the issue of stacked sugarcane, Zhang [

20] devised a rapid detection system for impurity levels in mechanically harvested sugarcane through segmental sampling. Samples must be arranged in a box and spread out for transport to the imaging system for image capture. The camera setup includes two units positioned equidistantly above and below, capturing images of impurity details on both the upper and lower surfaces of the sugarcane. These images are sent to a computer, where a deep learning model is utilized for training, assigning varying weight values to different impurities. Ultimately, the impurity content in the sugarcane segments is assessed based on the area ratio. Although this method addresses the stacking problem, it necessitates manual flattening of the samples, resulting in relatively low operational efficiency. Additionally, Jiang [

21] eliminated impurities from mechanically harvested raw sugarcane using an air selection device prior to weighing, successfully achieving impurity content detection. However, in real-world applications, the substantial weight of sugarcane samples places significant demands on the accuracy and responsiveness of the weighing equipment.

While existing research has made certain progress in the field of sugarcane detection, it generally suffers from limitations. These approaches often only partially address the mutual occlusion caused by densely stacked sugarcane, or focus on improving detection speed at the expense of accuracy, or enhance accuracy but cannot handle real-time, large-scale detection scenarios. Overall, no solution has yet emerged that can systematically and simultaneously overcome the following three major challenges: occlusion due to stacking, insufficient detection accuracy, and low detection efficiency.

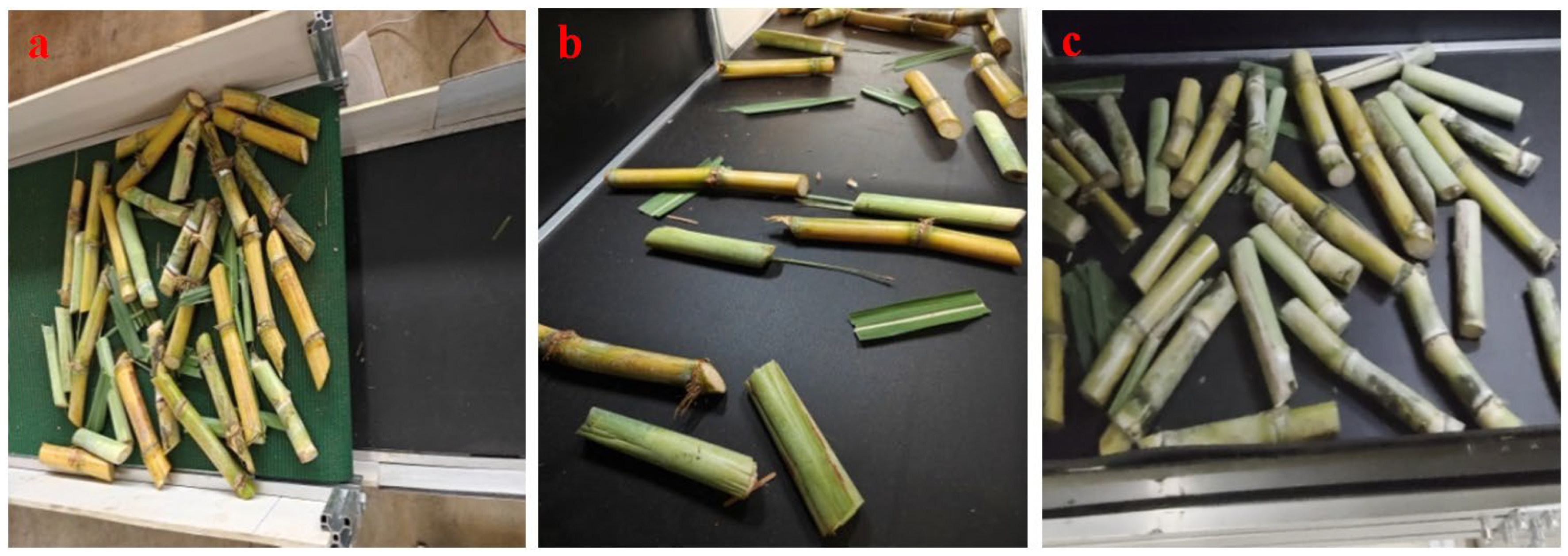

Therefore, addressing the problems identified in existing solutions, this paper proposes a hierarchical differential-speed device. This device utilizes a combination of a slow-speed conveyor belt and multi-stage adjustable baffles to gradually evacuate and orderly spread out the piled sugarcane, effectively eliminating stacking occlusion. Subsequently, the sugarcane falls in a single layer onto a high-speed conveyor belt, achieving rapid and stable transportation to the detection station. This fundamentally resolves the stacking issue at the source, significantly enhances conveying and detection efficiency, and provides the detection system with clear and stable target input, thereby fundamentally improving recognition accuracy and systematically overcoming the three key challenges in automated sugarcane detection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure and Working Principle of Grading Differential Device

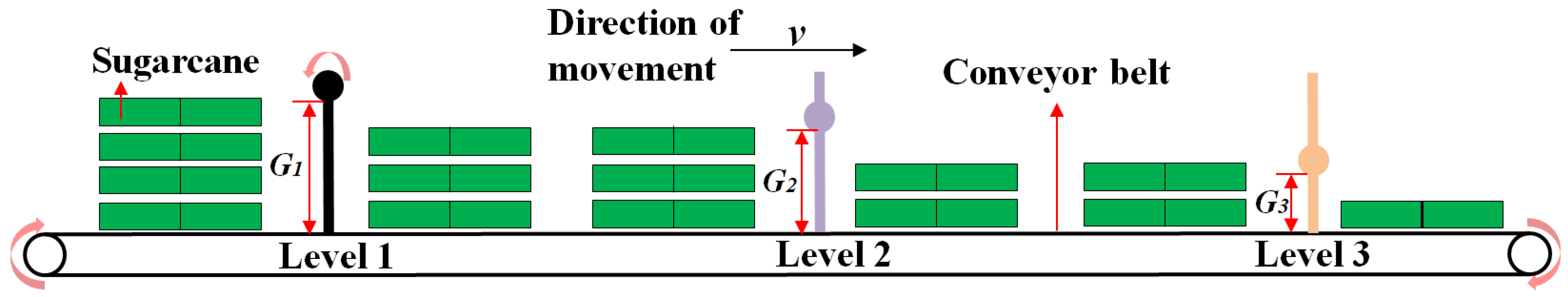

The differential grading apparatus outlined in this document is fundamentally made up of a tri-tier grading framework and a differential transmission mechanism. This tri-tier framework utilizes uniform ‘gate’ design elements, each incorporating a central element that consists of a rotating roller shaft and a stationary support. The primary role of this roller shaft is to significantly minimize the frictional resistance encountered by materials as they enter each grading element.

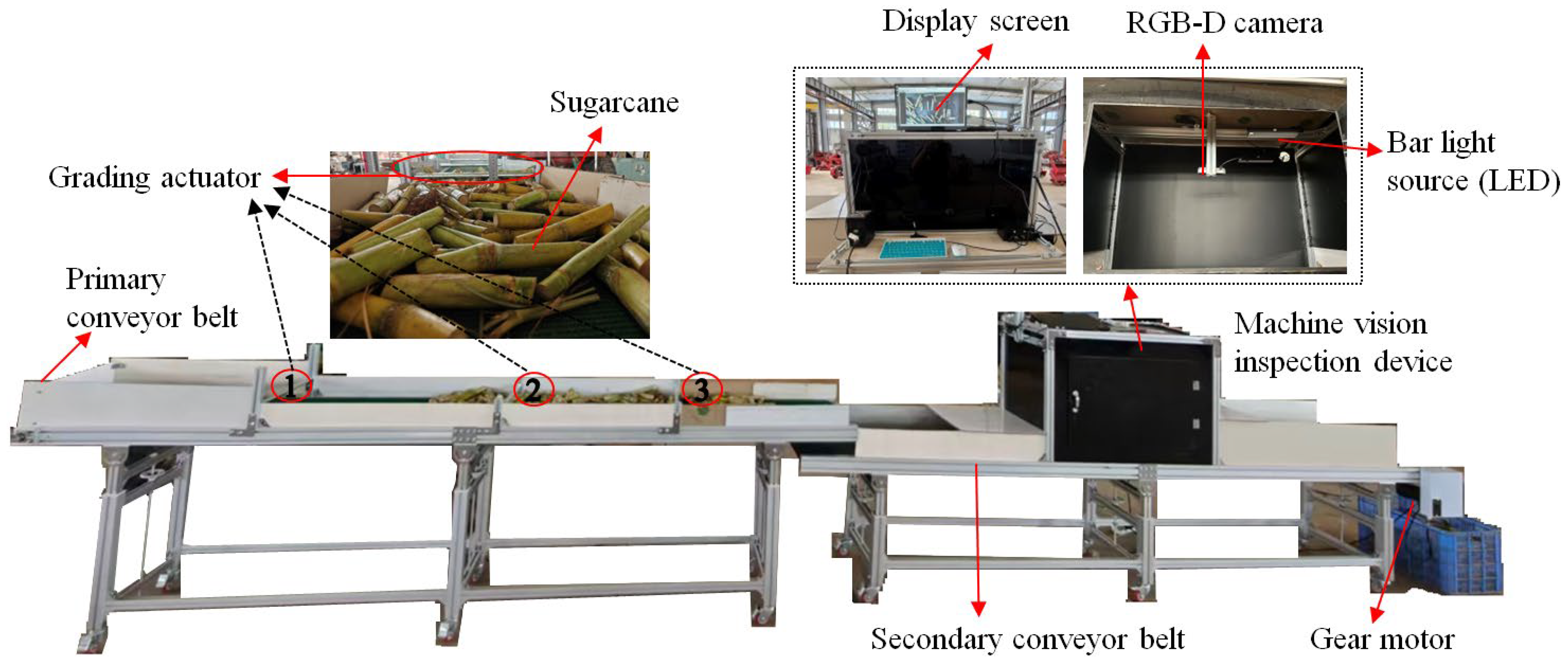

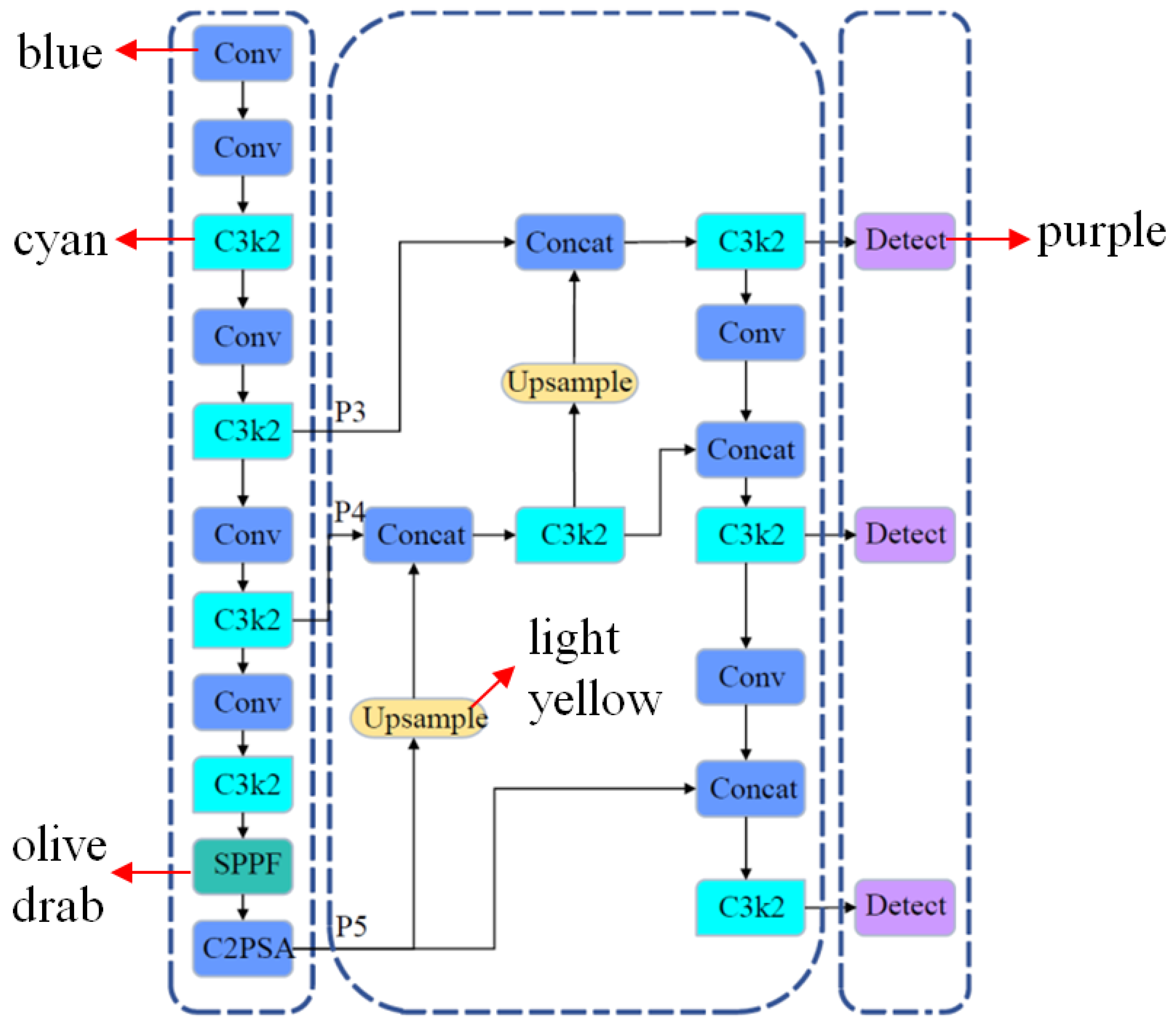

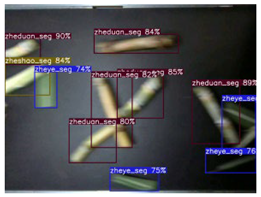

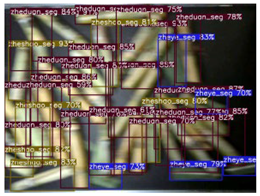

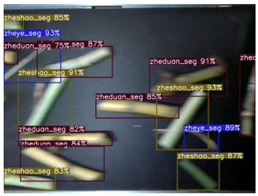

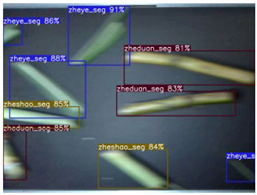

The three-tiered system is aligned with the direction of material transport and is mounted on a low-speed primary conveyor belt. The essential grading mechanism relies on the progressively decreasing gap between the roller axis and the conveyor belt’s working surface at the entry points of adjacent units. When sugarcane enters the first grading unit in a stacked formation (usually four layers), the uppermost layer is effectively removed due to the constraints of the gap and mechanical forces, while the remaining three layers proceed to the second grading unit. This process continues in the second unit, where the material layers are further reduced. After passing through the third grading unit, the material is transformed into a continuous single-layer configuration. Once the grading and thinning are complete, the single-layer sugarcane is moved to a secondary conveyor belt system, which operates at a higher speed than the primary belt. This increase in speed is intended to mitigate the challenges associated with the high stacking density of the single-layer sugarcane on the imaging detection system. The dense arrangement complicates the image recognition algorithms, leading to issues like overlapping target segmentation and unclear feature extraction, which can heighten the risk of misidentification and errors in the final recognition outcomes. By employing high-speed transport and leveraging the traction from the speed differential between the conveyor belts, the physical spacing between adjacent sugarcane stems can be effectively enhanced, significantly lowering the material’s surface density in the detection zone. This vital enhancement improves the imaging conditions for optical sensors, establishing a solid physical basis for subsequent high-accuracy and low-error-rate machine vision recognition. The differential intelligent detection device for sugarcane impurity rate classification is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Key Parameter Design

To meet the production requirements of sugar mills and address the issue of excessively high density after flattening caused by the initial stacking layers of sugarcane (4 layers, total thickness ≤ 110 mm), the design must satisfy three conditions: (1) Layer control: output a continuous single layer after three-stage processing, with a thickness ≤ 4 mm; (2) Density optimization: the proportion of sugarcane material occupying the conveyor belt area before and after processing ≤ 25%, meeting image recognition requirements; (3) Damage rate < 3%.

2.2.1. Geometric Distribution of Sugarcane Diameter

In order to assess the physical characteristics of sugarcane for the design of the roller-belt gap in the grading differential apparatus, 500 samples of the mature Yuetang 94–128 variety (aged between 8 to 10 months) were randomly collected from the sugarcane cultivation site at the Agricultural Machinery Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (located at 110°16′ E longitude and 21°9′ N latitude). A caliper was utilized to measure the diameter of the sugarcane samples, with the measurements conducted in a controlled environment of 25 ± 3 °C to prevent inaccuracies from thermal expansion of the stalks due to temperature variations, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

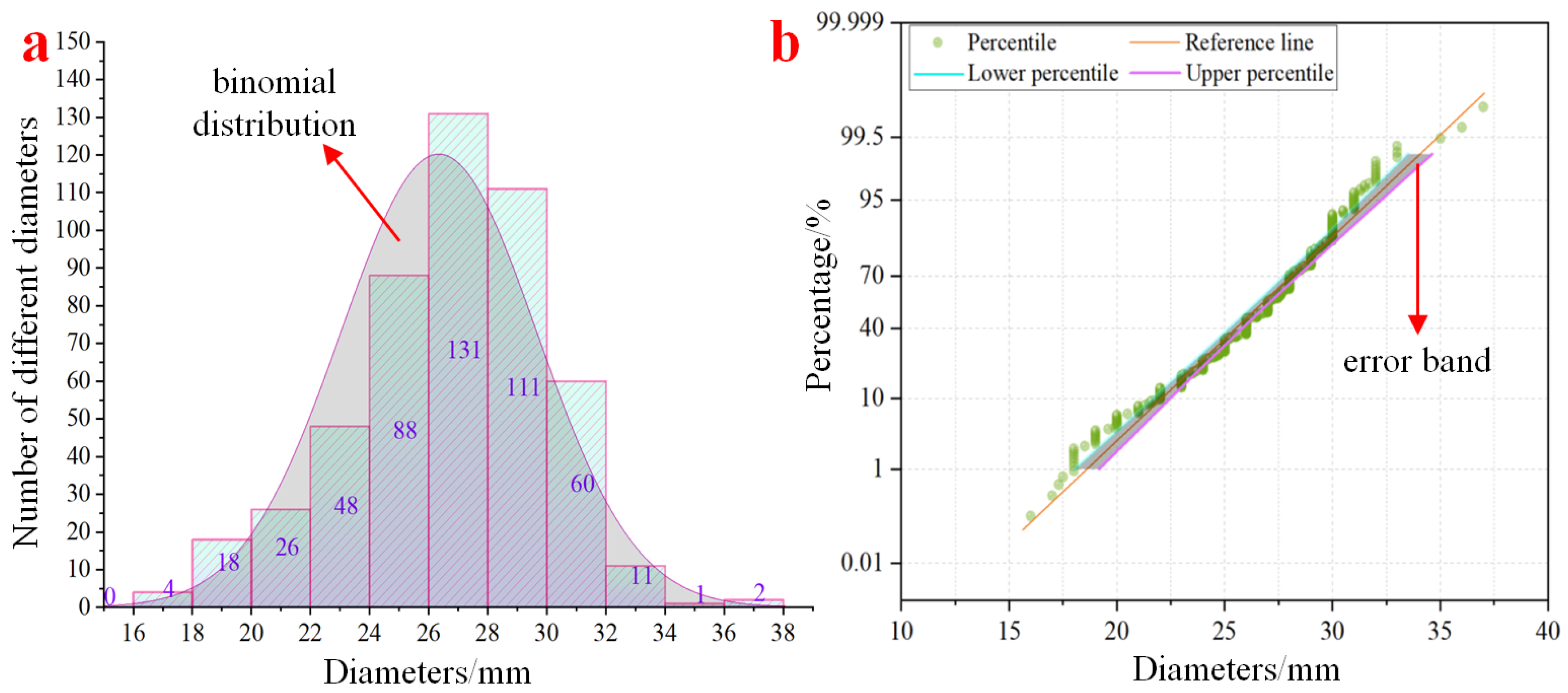

The analysis of 500 valid data entries during the preprocessing phase yielded the following findings: the smallest diameter measured is 16.0 mm, while the largest is 38.0 mm. The average diameter is calculated to be 26.3 mm, with a standard deviation of 3.3 mm, resulting in a coefficient of variation (CV) of 10.98%. The frequency distribution histogram (

Figure 3a) illustrates a unimodal and symmetric distribution, with the primary peak occurring between 26 mm and 28 mm (frequency of 131, representing 26.2%), and a secondary peak found in the 28 mm to 30 mm range (frequency of 111, or 22.2%). The interval from 24 mm to 26 mm comprises 17.6%, and collectively, these three intervals make up 66.0% of the total sample, indicating that the sugarcane diameters predominantly fall between 24 mm and 30 mm. To confirm the type of distribution, the sample data was evaluated using OriginPro 2018C software and subjected to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (K-S test, significance level θ = 0.05) for normality assessment. The computed statistic D

n = 0.028, with a critical value D

0.

05 ≈ 0.061, suggests that since D

n is less than D

0.05, the sugarcane diameters conform to a normal distribution. Additional validation through a probability plot (

Figure 3b) reveals a strong linear correlation coefficient R

2 = 0.991 between the sample quantiles and the theoretical normal quantiles, indicating a close fit to a normal distribution. Consequently, it is concluded that the diameter of the sugarcane follows a normal distribution

N (26.3, 3.3

2). This distribution characteristic is crucial for informing the design of the roller-belt gap G

n.

2.2.2. Geometric Constraint Equations

At the heart of the grading mechanism lies the geometric connection between the roller-belt and the diameter of the sugarcane, denoted as

Di. This relationship is founded on the laminated structure of the sugarcane and principles of rigid body constraints [

22]. The mathematical model representing this relationship is formulated as a double-layer inequality (1).

where:

n = a graded series.

k = the maximum number of layers that can be passed.

= the upper and lower limits of sugarcane diameter.

δc = the curvature compensation term to ensure that the sugarcane group can pass through the gap without blocking under the action of force.

δr = a dispersion correction term, which is used to offset the random fluctuation of layer thickness caused by the discreteness of sugarcane size.

However, the preconditions for the establishment of the equation are

(1) Every layer of sugarcane can be represented as a direct cylinder, with the distance between the centers of the layers meeting the following criteria:

where:

hi = the center distance between layers.

Di & Di+1 = the diameter of sugarcane.

Δh = sugarcane skin roughness compensation.

(2) The reaction force of the round roller to sugarcane should meet the stripping conditions:

where:

Fr = the reaction force of the round roller on the sugarcane.

mj = the quality of sugarcane.

g = the acceleration of gravity, which is set at 9.8 m/s2.

φ = the inlet angle.

Under actual harvesting conditions, non-ideal characteristics of sugarcane, such as curvature, morphological differences between internodes, and broken stalks, can lead to the partial failure of the geometric constraints in the hierarchical model (Equation (1)) established based on an idealized “stacked rigid cylinder”: the actual passage height of curved cane may exceed its equivalent diameter, periodic abrupt changes in internode diameter can breach the original upper and lower diameter limits, and broken stalks are prone to causing uncontrolled stacking numbers due to posture instability or the formation of clusters. These issues may trigger risks of insufficient grading, over-grading, or system blockage, necessitating the enhancement of model robustness through dynamic parameter correction and adaptive adjustment.

2.2.3. Gap Parameter Derivation

The grading interval Gn for sugarcane diameter must simultaneously meet two constraints, as determined by its statistical distribution properties.

(1) Geometric passability constraint (lower bound):

Ensure that the lower k − 1 layer of sugarcane can pass without being blocked.

(2) Layer stripping constraint (upper limit):

Prevents the

k layer and any layers above it from being stripped, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The specific parameter calculation process is as follows:

The objective for the initial gap

G1 is to remove the uppermost layer (from layer 4 to layer 3) while satisfying the specified criteria.

That is 78 mm < G1 < 104 mm.

Due to the unpredictable nature of sugarcane’s shape and layout, a safety margin coefficient of

α = 1.08 is applied and integrated into Formula (7). This leads to a calculation of

G1 as 98.2 mm, which is approximated to

G1 = 100 mm.

The constraint condition for the second-level gap

G2, which involves the target stripping layer transitioning from layer 3 to layer 2, is as follows:

That is 52 mm < G1 < 78 mm.

Based on the probability model with a confidence level of 95%, the cut-off value is

where:

μD(2) = the expected value of the second order statistic.

σD(2) is the standard deviation of the second-order statistic.

By replacing the values, we find that μD(2) equals 36 mm and σD(2) is 3.3 mm. Consequently, G2 is calculated to be 42.6 mm, which rounds up to 45 mm.

The constraint for the third-level gap

G3, which pertains to the output from layer 2 to layer 1, is as follows:

Based on the statistical measurements of sugarcane thickness, a theoretical inconsistency arises with the range of 38 mm <

G3 < 32 mm, leading to the implementation of the dynamic stiffness adjustment technique.

where:

β = the empirical correction coefficient (considering the randomness of sugarcane arrangement, vibration interference and other factors), which is set at 0.5 [

23].

E = the elastic modulus of sugarcane [

24], which is 15 MPa.

Davg = the average diameter of sugarcane.

ρ = sugarcane density.

vbelt = the running speed of the conveyor belt, which is set at 0.3 m/s.

As a result, by inputting the data, G3 is determined to be 31.38 mm, which rounds up to 33 mm.

2.2.4. Differential Transmission System

The mechanism takes advantage of the varying speeds of two conveyor belts to provide inertial acceleration to a single layer of sugarcane as it moves from the slower primary belt to the faster secondary belt. This process effectively increases the gap between neighboring sugarcane stalks. The distance separating the stalks can be determined using the velocity–displacement formula associated with uniformly accelerated linear motion. This distance indicates the displacement as the sugarcane transitions from speed

v1 on the primary belt to speed

v2 on the secondary belt, which can be calculated accordingly.

where: Δ

S = the separation distance.

a = the acceleration of sugarcane.

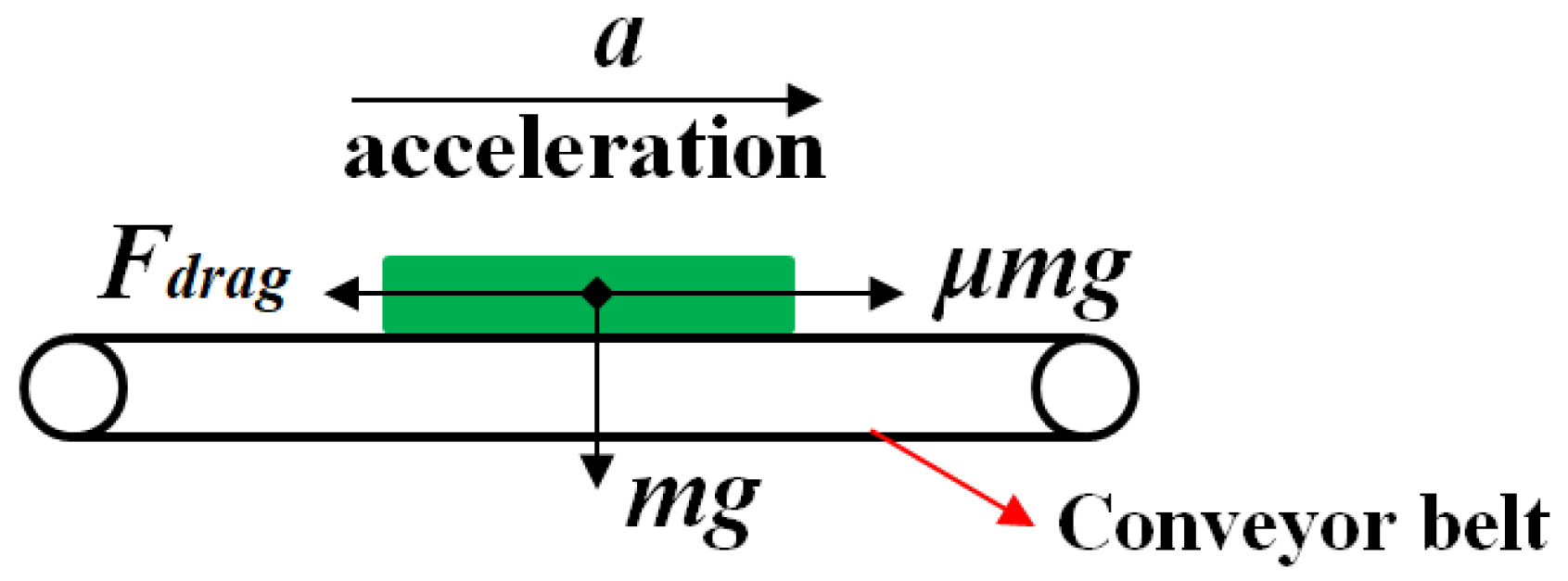

The speed at which sugarcane moves along the secondary conveyor belt is influenced by the combined effects of friction and resistance, illustrated in

Figure 5. The formula for this calculation is provided below.

where:

μk = the dynamic friction coefficient between sugarcane and the surface of the secondary conveyor belt, which is set at 0.6.

Fdrag = air resistance, which can be ignored.

To achieve the required minimum separation distance for image detection, the minimum velocity of the secondary conveyor belt can be calculated by inserting Δ

S = Δ

Smin into Equation (14). The detailed relationship is expressed as follows:

The constraint condition of the velocity ratio is shown in Formula (17).

2.3. Conveyor Belt Motor Power

The motor’s driving force for the conveyor belt must be precisely aligned with the requirements for transporting materials. This is primarily to counteract the friction between the materials and the belt, as well as the inherent resistance of the belt during operation. The formula for this calculation is

where:

Pm = the friction power of the material.

Pb = the resistance power of the conveyor belt itself.

η0 = the transmission efficiency, which is set at 0.85.

If we consider that the entire mass of the material conveyed in a single instance is 40 kg, the frictional force exerted by the material on the main conveyor belt is.

By replacing the values with μk1 = 0.6, v1 = 0.3 m/s, g = 9.8 m/s2, and Pm = 70.56 W, the result can be derived.

The energy needed to counteract the sliding resistance between the substance and the conveyor belt is

By substituting the data μb = 0.25, mb = 15 kg, Pb = 11.03 Kw can be obtained.

In conclusion, the primary conveyor belt’s total driving power is determined to be 81.59 watts, while the secondary conveyor belt’s total driving power is found to be 77.54 watts. The disparity in power output between the two belts arises from variations in material quality. The primary belt consists of four layers of sugarcane, which is four times denser than the material used in the secondary belt, compensating for the latter’s higher speed. Despite the secondary conveyor’s rapid movement, its lower material quality and reduced dynamic friction coefficient result in comparable total power outputs. Both conveyor belts are powered by a 120-watt deceleration motor (model 5IK90RGU-CF from Shenghe Motor Co., Ltd., located in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China), which has a 30% power margin to handle static friction during startup and to maintain stable operation under full load and other conditions.

4. Discussion

This research introduces a novel mechanism that combines geometric constraints with varying traction to facilitate the layered separation of sugarcane materials through a three-tiered roller belt gap design. Furthermore, it leverages the inertial force produced during sudden changes in speed to effectively increase the distance between the materials. This integrated method addresses the challenge of low accuracy in machine vision detection of impurities in densely stacked sugarcane. In the initial phase of the study, 500 samples of Yuetang 94–128 were gathered and analyzed using OriginPro 2018C software. The analysis, along with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test, confirmed that the sugarcane diameter adheres to a normal distribution (μ = 26.3 mm, σ = 3.3 mm).

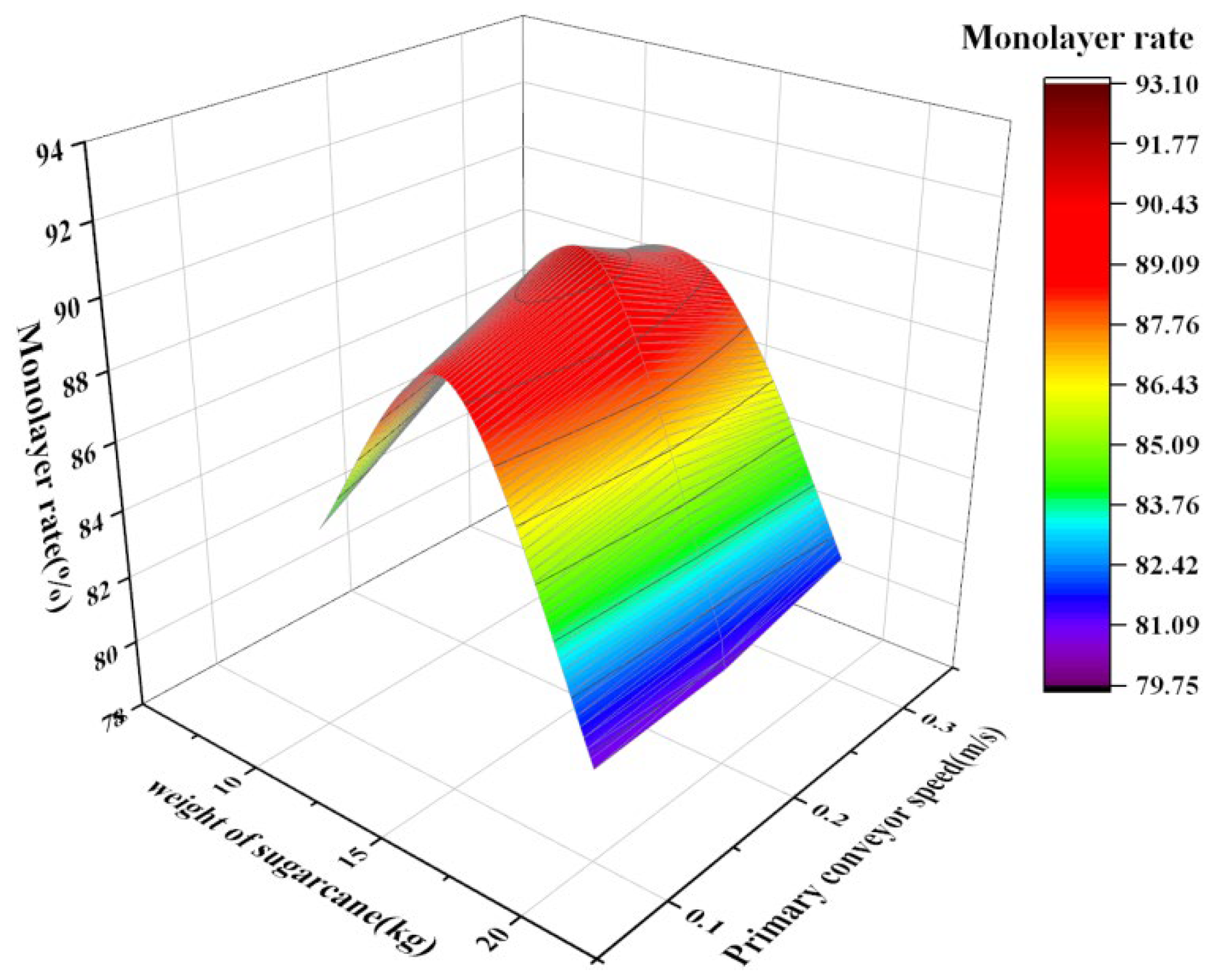

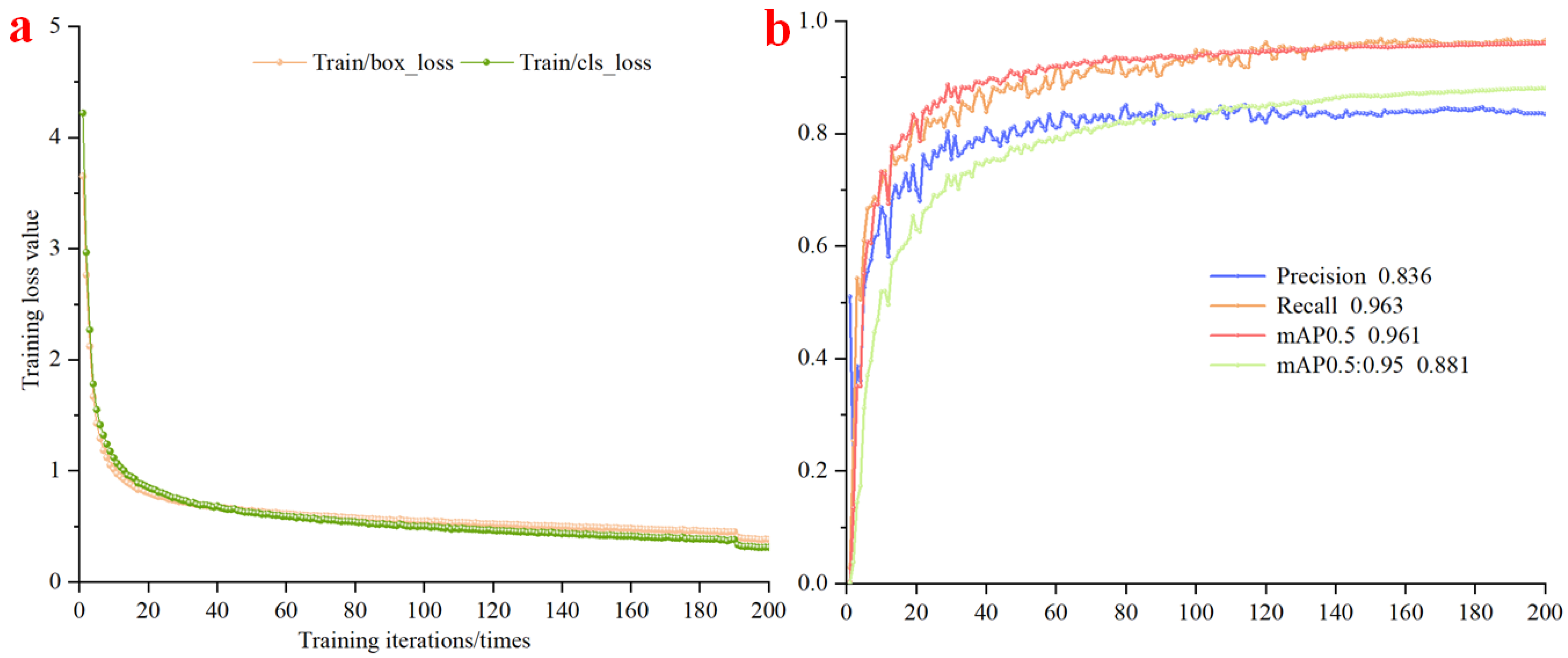

Building on the previously established groundwork, tests were carried out to evaluate the performance of the differential drive mechanism alongside machine vision detection assessments. The findings reveal that, at a significance threshold of α = 0.05, the weight of the sugarcane is a crucial determinant of the single-layer material rate; additionally, both the primary conveyor belt speed and the gear ratio exert a substantial influence on the material dispersion area ratio. Importantly, the F-statistic for the gear ratio is markedly greater than that for the conveyor belt speed, with a lower p-value, underscoring the gear ratio’s more significant role in managing the sugarcane distribution density. With optimized settings (sugarcane weight at 15 kg and conveyor belt speed at 0.2 m/s), the single-layer rate reached a maximum of 93.1%; concurrently, increasing the gear ratio from 3:1 to 5:1 led to a decrease in the area proportion from 26.8% to 22.0%, thereby enhancing the conditions for effective machine vision detection. The detection outcomes further indicate that the experimental group’s average accuracy was 94.90%, with only 2 instances of misidentification, while the control group achieved an average accuracy of just 67.97%, with 11 misidentified cases. This improvement translates to a 26.93% increase in recognition accuracy and an approximate 81.80% reduction in misidentifications, alongside a detection speed of 55.5 ms. These results convincingly demonstrate that the device not only enhances detection accuracy but also significantly lowers the rate of misidentifications.

Current techniques and devices for identifying impurities in sugarcane face several challenges. For example, Zheng’s [

18] method positions the detection apparatus at the rapid discharge point of the segmented sugarcane harvester, rendering it vulnerable to the influences of swift material flow and a dusty setting, which can compromise detection precision. Zheng’s [

19] technique employs a lifting transport system to regulate the detection volume, enhancing accuracy but failing to eliminate material accumulation. Zhang’s [

20] approach tackles the accumulation problem by manually distributing the material and using a dual-camera sampling box for detection; however, this leads to reduced operational efficiency. In contrast, the collaborative mechanism introduced in this research successfully addresses the limitations of these previous methods, facilitating effective and intelligent detection of impurity levels in sugarcane.

It is necessary to point out the technical limitations of this study. First, the experiments were based solely on a single sugarcane variety (Yuetan 94–128), and the parameters of the roller-belt clearance were fixed. This lacks adaptability to other sugarcane varieties and requires manual adjustment of the clearance. Second, the study assumed sugarcane as rigid cylindrical bodies and neglected the effects of deformation during actual operation. However, in real-world operations, sugarcane materials can experience blockages at the roller-belt clearance, requiring manual intervention for clearance, which challenges the continuity and efficiency of the detection process. Third, the uniform acceleration assumption neglects air resistance. At higher conveyor speeds, the separation distance between sugarcane stalks becomes denser. These limitations provide direction for optimizing the next generation of the device.

Future research should focus on the following: (1) integrating LiDAR or a real-time stereo vision system to measure the contour of sugarcane bundles and dynamically adjust the spacing between rollers, as well as the roller-belt clearance via servo motors to enhance adaptability across multiple varieties; (2) incorporating an automatic anti-blocking mechanism to ensure smooth material flow and maintain detection efficiency. The methodological framework established in this study holds significant potential for technological transfer and can be extended to the intelligent sorting and detection of other near-cylindrical agricultural materials, such as cassava and bamboo poles.