Time-Budget of Housed Goats Reared for Meat Production: Effects of Stocking Density on Natural Behaviour Expression and Welfare

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Animal Husbandry

2.2. Experimental Grouping

2.3. Behavioral Recording

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

- ●

- The 24 h period (%/24 h);

- ●

- 12 daylight hours (08:00 to 20:00) (%/daylight hours);

- ●

- 12 night hours (20:00 to 08:00) (%/night hours).

2.4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Associations Between Behavior and Stocking Density

2.4.2. Overall Time Budget and Time Interval Comparison

3. Results

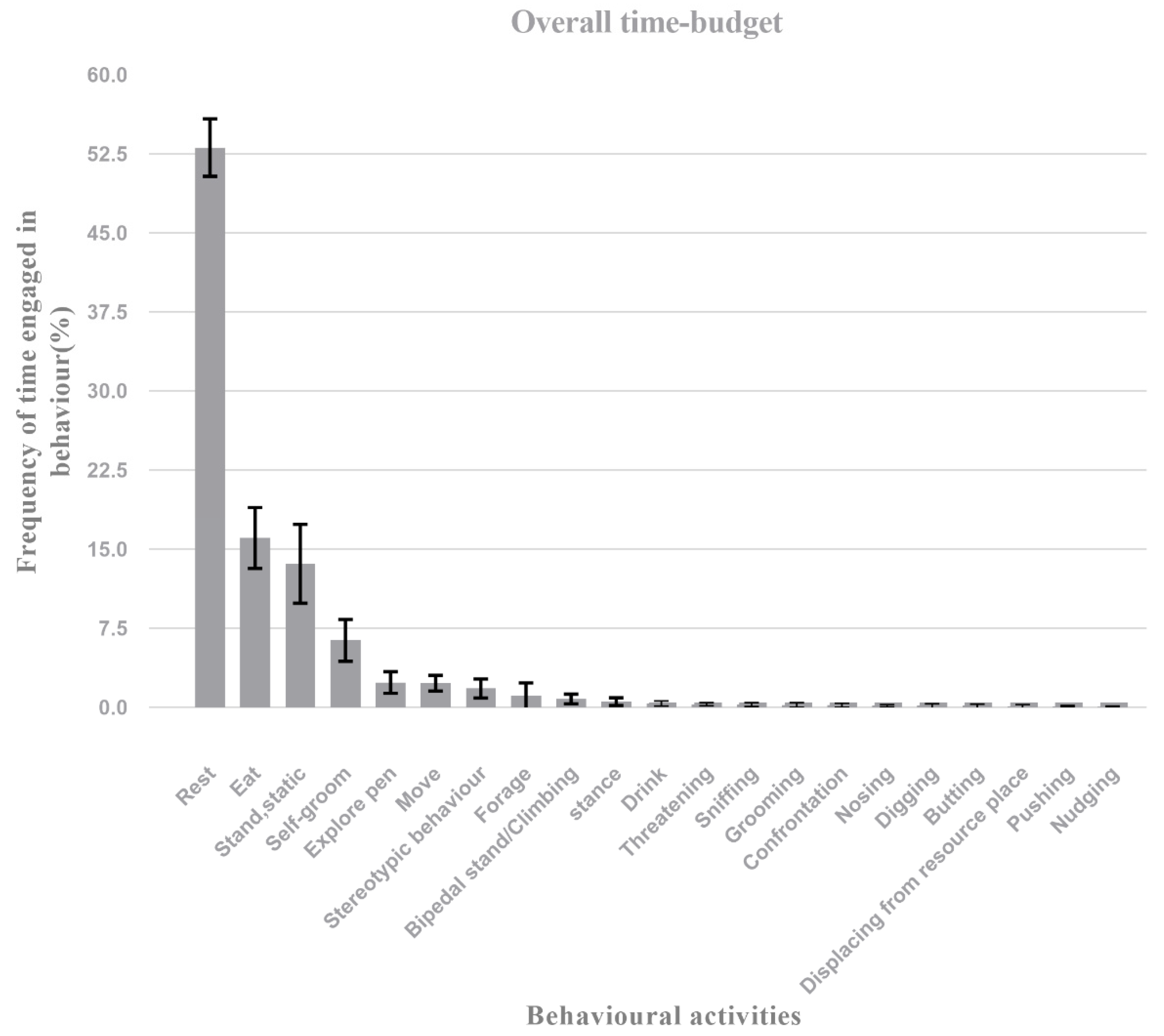

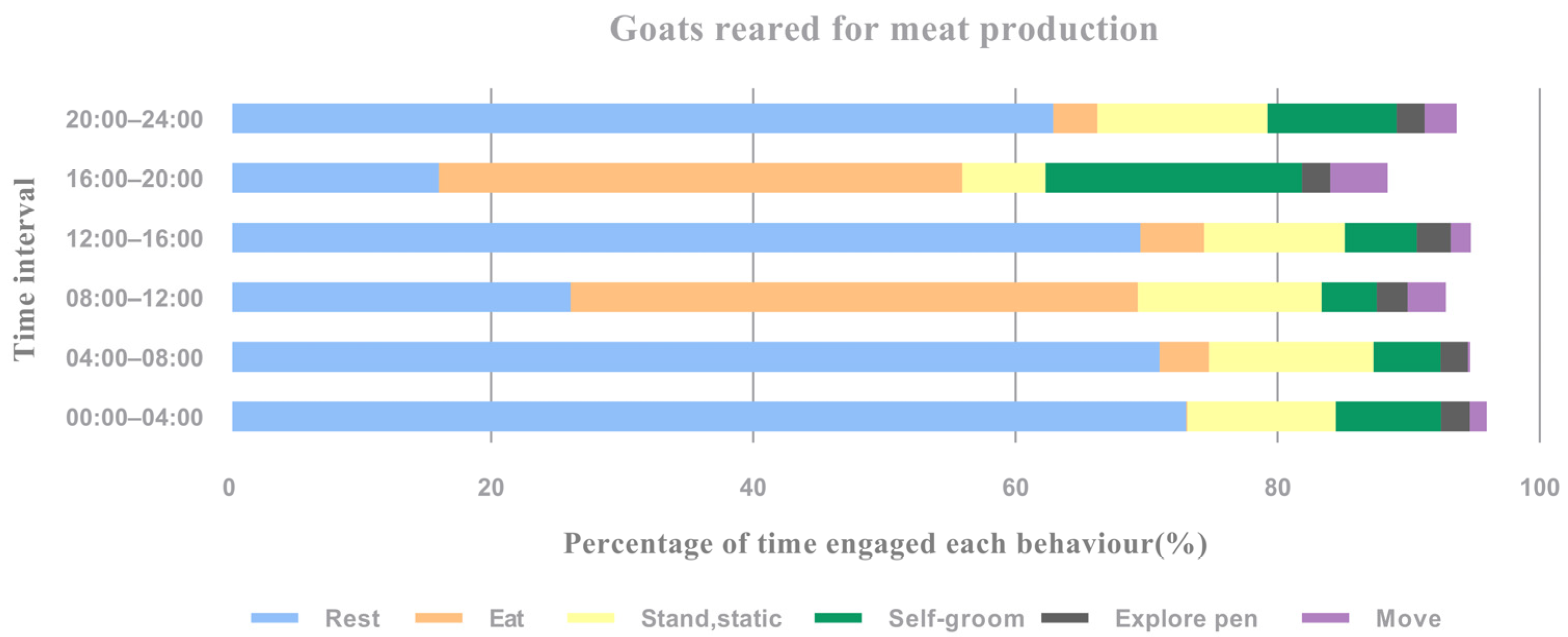

3.1. Overall Time Budget and Time Frame

3.2. Correlation Between Time Budget Within Group Pens and Stocking Density

4. Discussion

4.1. Contrasting Behavioral Patterns in Goats Under Intensive and Pasture-Based Systems

4.2. Eating Behavior Assessment

4.3. Standing and Resting Behavior Analysis

4.4. Increased Space Allowance Facilitates Natural Grooming Behaviors

4.5. Bipedal Stance and Behavioral Needs

4.6. Effects of Space Availability on Eating and Social Behavior

4.7. Stereotypic Behaviors as Early Warning Indicators

4.8. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeder, M.A.; Hesse, B. The initial domestication of goats (Capra hircus) in the Zagros Mountains 10,000 years ago. Sci. (Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci.) 2000, 287, 2254–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rharad, A.; El Aayadi, S.; Avril, C.; Souradjou, A.; Sow, F.; Camara, Y.; Hornick, J.; Boukrouh, S. Meta-analysis of dietary tannins in small ruminant diets: Effects on growth performance, serum metabolites, antioxidant status, ruminal fermentation, meat quality, and fatty acid profile. Animals 2025, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakram, N.; Mercha, I.; El Maadoudi, E.H.; Kabbour, R.; Douaik, A.; El Housni, A.; Naciri, M. Incorporating detoxified Argania spinosa press cake into the diet of Alpine goats affects the antioxidant activity and levels of polyphenol compounds in their milk. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 76, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.; Hornick, J.; Chentouf, M.; Cabaraux, J. Effects of Sulla flexuosa hay as alternative feed resource on goat’s milk production and quality. Animals 2023, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alders, R.G.; Campbell, A.; Costa, R.; Guèye, E.F.; Ahasanul Hoque, M.; Perezgrovas-Garza, R.; Rota, A.; Wingett, K. Livestock across the world: Diverse animal species with complex roles in human societies and ecosystem services. Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Crops and Livestock Products. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Du, L.; Li, J.; Ma, N.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, C.; Luo, J.; Liu, N.; Jia, Z.; Fu, C. Animal genetic resources in China: Sheep and goats. In China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resources; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 51, p. 151. ISBN 978-7-109-15881-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Dong, S.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Guo, Y.; Deng, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, G. Screening of SNP loci related to leg length trait in Leizhou goats based on whole-genome resequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, F.; Yun, Y.; Wang, X. Impact of anthocyanins derived from Dioscorea alata L. on growth performance, carcass characteristics, antioxidant capacity, and immune function of Hainan black goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1283947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.H.; Richardson, V.L.; Whittaker, A.L. How well does Australian animal welfare policy reflect scientific evidence: A case study approach based on lamb marking. Animals 2023, 13, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-De La Lama, G.C.; Mattiello, S. The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sabry, M.I.; Almasri, O. Stocking density, ambient temperature, and group size affect social behavior, productivity and reproductivity of goats—A review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, B.T.; Taylor, P.S.; Cowley, F.C.; Gaughan, J.B.; Morton, J.M.; Doyle, B.P.; Tait, L.A. The effects of stocking density on behavior and biological functioning of penned sheep under continuous heat load conditions. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, H.; Ruan, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, A. Effect of stocking density on behavior and pen cleanliness of grouped growing pigs. Agriculture 2022, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, K.; Drabik, K.; Wengerska, K.; Rozempolska-Rucińska, I. Effect of stocking density on behavioural and physiological traits of laying hens. Animals 2025, 15, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raspa, F.; Tarantola, M.; Bergero, D.; Nery, J.; Visconti, A.; Mastrazzo, C.M.; Cavallini, D.; Valvassori, E.; Valle, E. Time-budget of horses reared for meat production: Influence of stocking density on behavioural activities and subsequent welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.X.; Shao, D.F.; Li, S.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Azarfar, A.; Cao, Z.J. Effects of stocking density on behavior, productivity, and comfort indices of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3709–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weary, D.M.; Huzzey, J.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Board-invited review: Using behavior to predict and identify ill health in animals. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieli, B.; de Vitt, M.G.; Schogor, A.L.B.; Zotti, M.L.A.N.; Ferraz, P.F.P.; Zampar, A. Effect of grazing on the welfare of dairy cows raised under different housing conditions in compost barns. Animals 2024, 14, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.A.; Groarke, J.M. The importance of the social sciences in reducing tail biting prevalence in pigs. Animals 2019, 9, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Langbein, J.; Coulon, M.; Gabor, V.; Oesterwind, S.; Benz-Schwarzburg, J.; von Borell, E. Farm animal cognition—Linking behavior, welfare and ethics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, C.; Durand, M.; Largouët, C.; Dourmad, J.; Tallet, C. Effects of the environment and animal behavior on nutrient requirements for gestating sows: Future improvements in precision feeding. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 279, 115017–115034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, G.; Col, R.; Phillips, C.J.C. Effects of doubling the standard space allowance on behavioural and physiological responses of sheep experiencing regular and irregular floor motion during simulated sea transport. Animals 2020, 10, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozella, L.; Price, E.; Langford, J.; Lewis, K.E.; Cattuto, C.; Croft, D.P. Association networks and social temporal dynamics in ewes and lambs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 246, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houpt, K.A. Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-119-86113-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Ye, J.; Lin, X.; Xue, H.; Zou, X.; Liu, G.; Deng, M.; Sun, B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Identification of key functional genes and lncrnas influencing muscle growth and development in Leizhou black goats. Genes 2023, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhao, X.; Xue, H.; Zou, X.; Liu, G.; Deng, M.; Sun, B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. RNA-seq reveals miRNA and mRNA co-regulate muscle differentiation in fetal Leizhou goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 829769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Peng, W.; Mao, K.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Zeng, M.; Han, X.; Han, J.; Zhou, H. The changes in fecal bacterial communities in goats offered rumen-protected fat. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnig, A.; Zufferey, R.; Thomann, B.; Zwygart, S.; Keil, N.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Miserez, R.; Stucki, D.; Zanolari, P. Animal-based indicators for on-farm welfare assessment in goats. Animals 2021, 11, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.; Moggy, M.; Spooner, J. P-056 updating a 20-year-old code of practice for the care and handling of goats. Anim. Sci. Proc. 2023, 14, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Yadav, P.; Mahajan, A.; Anand, M.; Yadav, S.; Madan, A.K.; Yadav, B. Appropriate THI model and its threshold for goats in semi-arid regions of India. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 96, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbaş, A.A.; Elmaz, Ö.; Saatci, M. Comparative investigation of some behavior traits of Honamlı, Hair, and Saanen goats in a Mediterranean maquis Area. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2017, 41, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averós, X.; Lorea, A.; de Heredia, I.B.; Ruiz, R.; Marchewka, J.; Arranz, J.; Estevez, I. The behaviour of gestating dairy ewes under different space allowances. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fajardo, R.A.; Ortíz-Domínguez, G.; González-Pech, P.G.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.D.J. The complexity of goats’ feeding behaviour: An overview of the research in the tropical low deciduous forest. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 231, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, K.; Samaras, A.; Pavlidis, M.; Bizelis, I.; Laliotis, G.P. Social behaviour in lambs (Ovis aries) reared under an intensive system during the prepuberty period. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, N.J.; Sung, K.I. Behavioral and physiological changes during heat stress in Corriedale ewes exposed to water deprivation. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-De-Melo, A.; Ungerfeld, R.; Orihuela, A. Behavioral and physiological responses to early weaning in ewes and their single or twin lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puth, M.; Neuhäuser, M.; Ruxton, G.D. Effective use of Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient. Anim. Behav. 2014, 93, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, R.K.; Puth, M.; Neuhäuser, M.; Ruxton, G.D. Underestimation of Pearson’s product moment correlation statistic. Oecologia 2019, 189, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prion, S.; Haerling, K.A. Making sense of methods and measurement: Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2014, 10, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, W.; Yong, W.; Xi, O.Y. Observation studies of several behaviors of Tibetan goats. Ecol. Domest. Anim. 1992, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah, A. Chronophysiology of ruminant feeding behavior and metabolism: An evolutionary review. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2013, 44, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleena, J.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Beena, V.; Bhatta, R. Resilience of three indigenous goat breeds to heat stress based on phenotypic traits and pbmc hsp70 expression. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, F.E.; Basyony, M.A.; Abouelezz, S.S.; El-Bolkiny, Y.E.; Elshehry, S.T. Comparative study of heat stress effect on thermoregulatory and physiological responses of Baladi and Shami goats in Egypt. J. Anim. Poult. Prod. 2018, 9, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koluman Darcan, N.; Silanikove, N. The advantages of goats for future adaptation to climate change: A conceptual overview. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 163, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilja, S.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Mech, A.; David, C.G.; Kurien, E.K.; Varma, G.; Bhatta, R. Adaptive capability as indicated by behavioral and physiological responses, plasma HSP70 level, and PBMC HSP70 mRNA expression in Osmanabadi goats subjected to combined (heat and nutritional) stressors. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darcan, N.; Cedden, F.; Cankaya, S. Spraying effects on some physiological and behavioural traits of goats in a subtropical climate. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provolo, G.; Riva, E. One year study of lying and standing behaviour of dairy cows in a frestall barn in Italy. J. Agric. Eng. 2009, 40, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmanus, C.; Paludo, G.R.; Louvandini, H.; Gugel, R.; Sasaki, L.C.B.; Paiva, S.R. Heat tolerance in Brazilian sheep: Physiological and blood parameters. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mench, M.M.; Kuo, K.K.; Yeh, C.L.; Lu, Y.C. Comparison of thermal behavior of regular and ultra-fine aluminum powders (alex) made from plasma explosion process. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1998, 135, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.Q.; Liu, K.S.; Wu, W.; Li, J.S.; Zhao, T.C.; Shao, X.Q.; He, F.; Lv, H.; Li, X.L. Effect of stocking rate on grazing behaviour and diet selection of goats on cultivated pasture. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M.; Adebayo, R.A.; Nsahlai, I.V. Effects of diet and roughage quality, and period of the day on diurnal feeding behaviour patterns of sheep and goats under subtropical conditions. Anim. Biosci. 2019, 32, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervino, A.H.H.; Kaminishikawahara, C.M.; Soares, F.B.; Araújo, C.A.S.C.; Reis, L.F.; Rodrigues, F.A.M.L.; Vechiato, T.A.F.; Ferreira, R.N.F.; Barrêto-Júnior, R.A.; Mori, C.S.; et al. Behaviour of confined sheep fed with different concentrate sources. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zoo. 2014, 66, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animut, G.; Goetsch, A.L.; Aiken, G.E.; Puchala, R.; Detweiler, G.; Krehbiel, C.R.; Merkel, R.C.; Sahlu, T.; Dawson, L.J.; Johnson, Z.B.; et al. Grazing behavior and energy expenditure by sheep and goats co-grazing grass/forb pastures at three stocking rates. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 59, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghieri, A.; Pacelli, C.; Girolami, A.; Napolitano, F. Time budget, social and ingestive behaviours expressed by native beef cows in mediterranean conditions. Livest. Sci. 2011, 141, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.M. Farming sheep and goats. In Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; Chapter 8; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Heleski, C.R.; Shelle, A.C.; Nielsen, B.D.; Zanella, A.J. Influence of housing on weanling horse behavior and subsequent welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 78, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D. Horse behaviour: Evolution, domestication and feralization. In The Welfare of Horses; Waran, N., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, B.B.; Duthie, C.; Corbishley, A.; Mason, C.; Bowen, J.M.; Bell, D.J.; Haskell, M.J. Intrinsic calf factors associated with the behavior of healthy pre-weaned group-housed dairy-bred calves. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1204580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, F.; Knierim, U.; Grass, F.; De Rosa, G. Positive indicators of cattle welfare and their applicability to on-farm protocols. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornale, P.; Macchi, E.; Miretti, S.; Renna, M.; Lussiana, C.; Perona, G.; Mimosi, A. Effects of stocking density and environmental enrichment on behavior and fecal corticosteroid levels of pigs under commercial farm conditions. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 10, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Malik, D.S.; Kaswan, S.; Saini, A.L. Effect of different floor space allowances on the performance and behavior of Beetal kids under stall-fed conditions. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2017, 51, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.H. Effect of some managerial practices on behaviour and performance of Egyptian Balady goats. Glob. Vet. 2014, 13, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bojkovski, D.; Atuhec, I.; Kompan, D.; Zupan, M. The behavior of sheep and goats co-grazing on pasture with different types of vegetation in the karst region. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Kamboj, M.L.; Vanita, B.; Raza, M. Behavioral adaptations of gaddi goats: Validation of seasonal resource utilization in transhumant pastoralism of the north-western Himalayan region. J. Vet. Behav. 2025, 79, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlenbruch, R.; Jørgensen, G.H.M.; Andersen, I.L.; Bøe, K.E. Provision of additional walls in the resting area—The effects on resting behaviour and social interactions in goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 122, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Prentice, P.M.; Mcelligott, A.G. Individual personality differences in goats predict their performance in visual learning and non-associative cognitive tasks. Behav. Process. 2017, 134, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, H.M.; Johansen, F.P.; Meagher, R.K. Evaluating the consistency of dairy goat kids’ responses to two methods of assessing fearfulness. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 272, 106209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramati, M.; Dezfouli, A.; Piray, P. Speed/accuracy trade-off between the habitual and the goal-directed processes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkemeier, M.; Oesterwind, S.; Nürnberg, G.; Puppe, B.; Langbein, J. Assessment of personality types in Nigerian dwarf goats (Capra hircus) and cross-context correlations to behavioural and physiological responses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 217, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoult, C.M.C.; Osthaus, B.; Hildebrand, A.C.G.; Mcelligott, A.G.; Nawroth, C. Goats show higher behavioural flexibility than sheep in a spatial detour task. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölü, C. Effects of forage-to-concentrate ratio on abnormal stereotypic behavior in lambs and goat kids. Animals 2025, 15, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, K.A.R.; Valentim, J.K.; Lemke, S.S.R.; Dallago, G.M.; Vargas, R.C.; Paiva, A.L.D.C. Behavior of Saanen dairy goats in an enriched environment. Acta Sci.-Anim. Sci. 2018, 40, e42454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzuino, K.; Bell, N.J.; Bazeley, K.J.; Nicol, C.J. Assessment of welfare on 24 commercial UK dairy goat farms based on direct observations. Vet. Rec. 2010, 167, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G.J.; Latham, N.R. Can’t stop, won’t stop: Is stereotypy a reliable animal welfare indicator? Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, S57–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G.; Rushen, J. (Eds.) Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare and Beyond; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2006; pp. 325–356. ISBN 978-1-84593-465.

- Battini, M.; Vieira, A.; Barbieri, S.; Ajuda, I.; Stilwell, G.; Mattiello, S. Invited review: Animal-based indicators for on-farm welfare assessment for dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, M.; Atuhec, I.; Jordan, D. The effect of an irregular feeding schedule on equine behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2020, 23, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumans, I.J.M.M.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Hofstede, G.J.; Bokkers, E.A.M. How social factors and behavioural strategies affect feeding and social interaction patterns in pigs. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 194, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırır, M.; Daş, G.; Lambertz, C.; Gauly, M. Feeding, resting and agonistic behavior of pregnant Boer goats in relation to feeding space allowance. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2019, 19, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, D.A.; Friend, T.H.; Dellmeier, G.R.; Nuti, L.C. Behavioral and physiological responses of dairy goats to food thwarting. Physiol. Behav. 1992, 51, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, D.T.T.; Mui, N.T.; Ledin, I. Effect of group size on feed intake, aggressive behaviour and growth rate in goat kids and lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 72, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, A.; Gipson, T.A.; Puchala, R.; Askar, A.R.; Tesfai, K.; Detweiler, G.D.; Asmare, A.; Goetsch, A.L. Effects of stocking rate, breed and stage of production on energy expenditure and activity of meat goat does on pasture. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2009, 36, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogarten, J.F.; Bonnell, T.R.; Brown, L.M.; Campenni, M.; Wasserman, M.D.; Chapman, C.A. Increasing group size alters behavior of a folivorous primate. Int. J. Primatol. 2014, 35, 590–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, A.; Casamassima, D.; Pulina, G.; Pazzona, A. Factors of welfare reduction in dairy sheep and goats. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, I.L.; Tønnesen, H.; Estevez, I.; Cronin, G.M.; Bøe, K.E. The relevance of group size on goats’ social dynamics in a production environment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 134, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J.; Johnson, P.; Olson, K. Classifying season long livestock grazing behavior with the use of a low-cost GPS and accelerometer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 181, 105957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, Y.; Otmani, S.E.; Chentouf, M.; Hornick, J.; Bindelle, J.; Cabaraux, J. Foraging behavior of goats browsing in southern mediterranean forest rangeland. Animals 2020, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, R.J.; Patel, N.R.; Wadhwani, K.N. Effect of floor types and seasons on behavioural activities of surti goats. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 91, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smid, A.M.C.; Burgers, E.E.A.; Weary, D.M.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Dairy cow preference for access to an outdoor pack in summer and winter. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, K.T.; Deniz, M.; Vale, M.M.D.; Dittrich, J.R.; Hötzel, M.J. Influence of microclimate on dairy cows’ behavior in three pasture systems during the winter in south Brazil. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Id Pen | N of Goats | Pen Area (m2) | Stocking Density (m2/Goat) | Space at Feed Bunk (m/Goat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 6 | 12.5 | 2.0 | 0.21 |

| MD | 12 | 12.5 | 1.0 | 0.21 |

| HD | 24 | 12.5 | 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Type | Behaviour | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| States | Rest | Lying on the ground in a sternal position with legs bent underneath the body, or in a lateral position with legs extended. |

| Eat | Standing at the feed trough with the head completely inside one of the feeders. | |

| Stand, static | Standing on four legs on the ground without any other movement. | |

| Self-groom | Grooming by self-licking, scratching with a hind leg, or rubbing against pen fixtures. | |

| Move | Changing location within the pen by walking or running. | |

| Explore pen | Interacting with the pen walls or other physical structures using the nose. | |

| Forage | Standing with the head down, interacting with forage. | |

| Bipedal stance /Climbing | Placing the front legs on the railings or the mineral block trough while the hind legs remain in contact with the ground, so that the body is no longer parallel to the ground/The act of climbing onto pen structures. | |

| Lick mineral resource | Standing by the mineral supplement point and licking it. | |

| Drink | Standing by the drinker and using it. | |

| Digging | Alternating forehoof scraping of the ground (a grooming/clearing behavior). | |

| Stereotypies | Pen licking, Gnawing | Stereotypic licking or gnawing directed at pen structures or other objects. |

| Events | Negative social interaction | |

| Threatening | Threatening posture by orienting the forehead towards a conspecific without physical contact. | |

| Confrontation | Confrontational butting followed by a static push | |

| Butting | Aggressive butting (sudden, vigorous head contact). | |

| Displacing from resources | Forcing another goat to leave a resource point (e.g., feed trough, drinker, mineral supplement block, or resting area). | |

| Pushing | Using a body part (other than the head) to push another goat. | |

| Positive social interaction | ||

| Sniffing | Smelling any part of another goat’s body with the nose | |

| Nosing | Gently touching another goat with the nose. | |

| Allogrooming | Cleaning another goat’s wool with the mouth. | |

| Nudging | Gently and mildly pushing another goat. |

| Behavioural Activities (%) | Overall Time Budget | 00:00–04:00 | 04:00–08:00 | 08:00–12:00 | 12:00–16:00 | 16:00–20:00 | 20:00–24:00 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 53.09 ± 2.72 | 73.00 ±6.22 | 70.98 ± 6.78 | 26.07 ± 10.05 | 69.53 ± 5.72 | 16.03 ± 5.20 | 62.88 ± 5.70 |

| Eat | 16.05 ± 2.88 | 0.09 ± 0.26 | 3.76 ± 3.04 | 43.26 ± 9.06 | 4.86 ± 3.15 | 39.90 ± 9.25 | 3.36 ± 4.16 |

| Stand, static | 13.60 ± 3.73 | 11.34 ± 4.76 | 12.56 ± 6.00 | 14.00 ± 5.50 | 10.71 ± 2.70 | 19.59 ± 8.25 | 12.96 ± 7.60 |

| Self-groom | 6.36 ± 1.98 | 8.02 ± 3.08 | 5.12 ± 1.88 | 4.22 ± 2.14 | 5.50 ± 2.71 | 6.34 ± 2.65 | 9.87 ± 3.67 |

| Move | 2.30 ± 0.75 | 2.20 ± 2.43 | 2.08 ± 1.19 | 2.37 ± 2.09 | 2.58 ± 1.76 | 2.14 ± 1.18 | 2.14 ± 1.69 |

| Explore pen | 2.36 ± 1.02 | 1.30 ± 0.91 | 1.56 ± 1.61 | 2.92 ± 0.88 | 1.56 ± 1.07 | 4.40 ± 1.62 | 2.43 ± 1.38 |

| Forage | 1.09 ± 1.22 | 0.46 ± 0.43 | 0.87 ± 1.30 | 1.59 ± 1.67 | 1.24 ± 2.68 | 2.17 ± 2.58 | 0.35 ± 0.45 |

| Stereotypies | 1.79 ± 0.91 | 1.30 ± 0.77 | 0.98 ± 0.83 | 0.81 ± 0.64 | 1.27 ± 1.20 | 3.56 ± 3.16 | 3.04 ± 2.02 |

| Bipedal stance/ Climbing | 0.80 ± 0.46 | 0.46 ± 0.70 | 0.87 ± 0.58 | 1.01 ± 1.25 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 1.68 ± 1.29 | 0.81 ± 0.24 |

| Lick mineral resource | 0.54 ± 0.378 | 0.17 ± 0.29 | 0.17 ± 0.23 | 1.04 ± 0.93 | 0.93 ± 0.84 | 0.64 ± 0.76 | 0.38 ± 0.47 |

| Drink | 0.36 ± 0.23 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.35 | 0.69 ± 0.68 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 1.22 ± 0.81 | 0.14 ± 0.26 |

| Sniffing | 0.26 ± 0.19 | 0.17 ± 0.29 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.23 ± 0.38 | 0.32 ± 0.48 | 0.52 ± 0.69 | 0.32 ± 0.45 |

| Threatening | 0.28 ± 0.15 | 0.49 ± 0.42 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.52 ± 0.77 | 0.26 ± 0.37 | 0.20 ± 0.31 | 0.12 ± 0.23 |

| Confrontation | 0.20 ± 0.18 | 0.41 ± 0.63 | 0.14 ± 0.23 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.43 ± 0.55 | 0.35 ± 0.58 | 0.03 ± 0.09 |

| Allogrooming | 0.20 ± 0.21 | 0.06 ± 0.11 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.26 ± 0.69 | 0.23 ± 0.38 | 0.23 ± 0.46 | 0.41 ± 0.43 |

| Butting | 0.14 ± 0.17 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.09 ± 0.18 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 0.26 ± 0.37 | 0.23 ± 0.53 |

| Digging | 0.14 ± 0.19 | 0.17 ± 0.37 | 0.12 ± 0.35 | 0.23 ± 0.69 | 0.12 ± 0.35 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.12 ± 0.35 |

| Displacing from resources | 0.11 ± 0.14 | 0.029 ± 0.09 | 0.12 ± 0.35 | 0.06 ± 0.11 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.38 ± 0.68 | 0.12 ± 0.35 |

| Nosing | 0.15 ± 0.11 | 0.09 ± 0.18 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.14 ± 0.35 | 0.14 ± 0.35 | 0.23 ± 0.30 |

| Pushing | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.17 | 0.23 ± 0.40 | 0.12 ± 0.35 | 0.20 ± 0.36 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| Nudging | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 0.14 ± 0.35 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.09 ± 0.18 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.18 |

| Behaviour | Stocking Density | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/24 h | %/12 h Daylight Hours | %/12 h Night Hours | ||||

| r a | p-Value | r a | p-Value | r a | p-Value | |

| Rest | 0.19 | 0.623 | −0.54 | 0.137 | 0.68 | 0.046 * |

| Eat | −0.04 | 0.927 | 0.16 | 0.683 | −0.27 | 0.485 |

| Stand, static | −0.91 | 0.001 ** | −0.73 | 0.025 * | −0.87 | 0.003 ** |

| Self-groom | 0.93 | 0.000 ** | 0.61 | 0.080 | 0.88 | 0.002 ** |

| Move | −0.05 | 0.903 | −0.30 | 0.440 | −0.02 | 0.959 |

| Explore pen | 0.34 | 0.372 | 0.43 | 0.251 | 0.27 | 0.483 |

| Forage | 0.58 | 0.100 | 0.55 | 0.125 | 0.32 | 0.403 |

| Stereotypies | 0.22 | 0.564 | −0.05 | 0.902 | 0.63 | 0.069 |

| Bipedal stance/Climbing | 0.71 | 0.033 * | 0.63 | 0.068 | 0.46 | 0.207 |

| Lick mineral resource | −0.70 | 0.035 * | −0.55 | 0.126 | −0.80 | 0.010 ** |

| Drink | −0.60 | 0.086 | −0.47 | 0.205 | −0.60 | 0.090 |

| Sniffing | −0.32 | 0.396 | −0.35 | 0.359 | −0.55 | 0.121 |

| Threatening | −0.40 | 0.281 | 0.02 | 0.953 | −0.55 | 0.123 |

| Confrontation | −0.76 | 0.018 * | −0.65 | 0.058 | −0.71 | 0.033 * |

| Allogrooming | 0.43 | 0.249 | 0.56 | 0.114 | −0.18 | 0.650 |

| Butting | −0.30 | 0.441 | −0.25 | 0.523 | −0.31 | 0.418 |

| Digging | 0.65 | 0.060 | 0.66 | 0.056 | 0.55 | 0.124 |

| Displacing from resources | 0.56 | 0.114 | 0.22 | 0.565 | 0.43 | 0.250 |

| Nosing | −0.58 | 0.103 | 0.11 | 0.780 | −0.40 | 0.282 |

| Pushing | 0.60 | 0.089 | 0.68 | 0.044 * | .c | .c |

| Nudging | −0.15 | 0.692 | −0.29 | 0.456 | 0.14 | 0.714 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, M.; Yan, B.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Peng, W.; Liu, H.; Ji, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Time-Budget of Housed Goats Reared for Meat Production: Effects of Stocking Density on Natural Behaviour Expression and Welfare. Agriculture 2026, 16, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010043

Zeng M, Yan B, Zhou H, Wu Q, Wang K, Yang Y, Peng W, Liu H, Ji C, Zhang X, et al. Time-Budget of Housed Goats Reared for Meat Production: Effects of Stocking Density on Natural Behaviour Expression and Welfare. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Meng, Bin Yan, Hanlin Zhou, Qun Wu, Ke Wang, Yuanting Yang, Weishi Peng, Hu Liu, Chihai Ji, Xiaosong Zhang, and et al. 2026. "Time-Budget of Housed Goats Reared for Meat Production: Effects of Stocking Density on Natural Behaviour Expression and Welfare" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010043

APA StyleZeng, M., Yan, B., Zhou, H., Wu, Q., Wang, K., Yang, Y., Peng, W., Liu, H., Ji, C., Zhang, X., & Han, J. (2026). Time-Budget of Housed Goats Reared for Meat Production: Effects of Stocking Density on Natural Behaviour Expression and Welfare. Agriculture, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010043