Adsorption/Desorption Behaviour of the Fungicide Cymoxanil in Acidic Agricultural Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soils

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Adsorption and Desorption Experiments

2.4. Cymoxanil Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of Soils

3.2. Adsorption Behaviour of Cymoxanil in Soils

3.3. Desorption Behaviour of Cymoxanil in Soils

3.4. Influence of Soil Properties on Cymoxanil Adsorption Behaviour

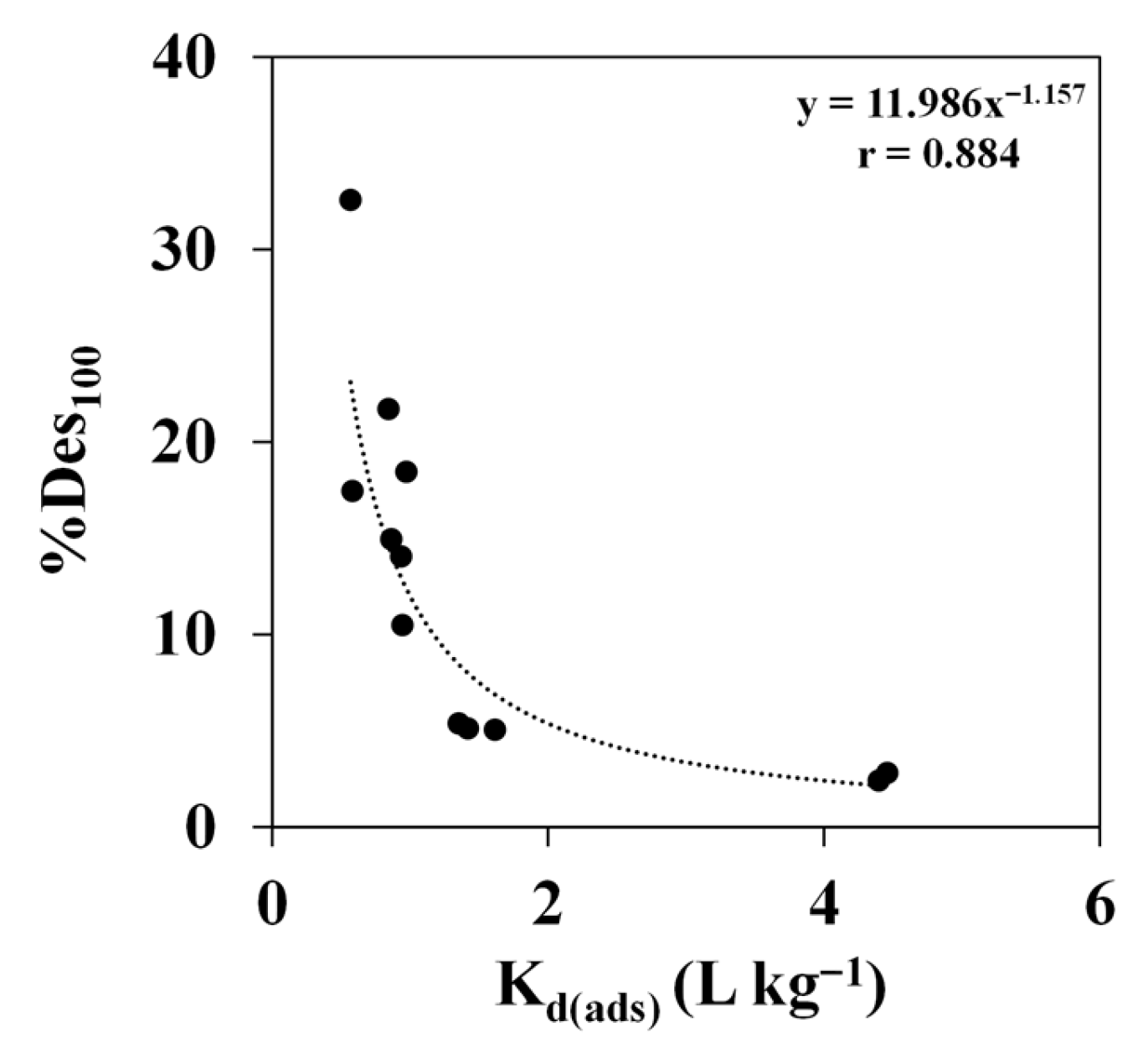

3.5. Influence of Soil Properties on Cymoxanil Desorption Behaviour

Adjusted R2 = 0.781; F = 40.132; p = 0.000

Adjusted R2 = 0.832; F = 55.391; p = 0.000

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, S.; Nigar, R.; Zhong, G.; Li, J.; Geng, X.; Yi, X.; Tian, L.; Bing, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G. Occurrence and fate of current-use pesticides in Chinese forest soils. Environ. Res. 2024, 255, 119087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD-FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2012; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Pesticide Use. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RP (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Silva, V.; Mol, H.G.J.; Zomer, P.; Tienstra, M.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils—A hidden reality unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Sanghvi, G.; Yadav, M.; Padhiyar, H.; Christian, J.; Singh, V. Fate of pesticides in agricultural runoff treatment systems: Occurrence, impacts and technological prodress. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 117100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.; Kim, D.; Jeong, W.-T. Environmental Fate and Sustainable Management of Pesticides in Soils: A Critical Review Focusing on Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Bahar, M.M.; Naidu, R. Diffuse soil pollution from agriculture: Impacts and remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Estévez, M.; López-Periago, E.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Mejuto, J.-C.; García-Río, L. The mobility and degradation of pesticides in soils and the pollution of groundwater resources. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 123, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Rasool, T.; Gani, K.M. A review of interactions of pesticides within various interfaces of intrinsic and organic residue amended soil environment. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 11, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zeng, G.; Tang, L.; Wang, J.; Wan, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Yi, H.; Ye, S.; Deng, R. Sorption, transport and biodegradation—An insight into bioavailability of persistent organic pollutants in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M. Fate of Pesticides in the Environment and its Bioremediation. Eng. Life Sci. 2005, 5, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwieląg-Piasecka, I. Soil Organic Matter Composition and pH as Factors Affecting Retention of Carbaryl, Carbofuran and Metolachlor in Soil. Molecules 2023, 28, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Massoud, A.H.; Derbalah, A.S.; Al-Brakati, A.; Al-Abdawani, M.A.; Eltahir, H.A.; Yanai, T.; Elmahallawy, E.K. Biochemical and Histopathological Alterations in Different Tissues of Rats Due to Repeated Oral Dose Toxicity of Cymoxanil. Animals 2020, 10, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varodi, C.; Pogăcean, F.; Coros, M.; Magerusan, L.; Stefan-van Staden, R.-I.; Pruneanu, S. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nitrogen, Boron Co-Doped Graphene with Enhanced Electro-Catalytic Activity for Cymoxanil Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Li, L. Residues, dissipation, and dietary risk assessment of oxadixyl and cymoxanil in cucumber. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 917334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPDB, Pesticide Properties DataBase, University of Hertfordshire. 2025. Available online: https://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/ppdb/en/Reports/196.htm (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Druart, C.; Millet, M.; Scheifler, R.; Delhomme, O.; Raeppel, C.; de Vaufleury, A. Snails as indicators of pesticide drift, deposit, transfer and effects in the vineyard. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4280–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martín, A.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Pose-Juan, E.; Rodríguez-Cruz, S. Effect of different rates of spent mushroom substrate on the dissipation and bioavailability of cymoxanil and tebuconazole in an agricultural soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Dacal, A.; Hernández-Marrero, M.E.; Rial-Berriel, C.; Díaz-Díaz, R.; Bernal-Suárez, M.M.; Zumbado, M.; Henríque-Hernández, L.A.; Boada, L.D.; Luzardo, O.P. Comparative study of organic contaminants in agricultural soils at the archipelagos of the Macaronesia. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 301, 118979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaki, R.; Ziaee, M.; Mahdavi, V. Pesticide residues in corn and soil of corn fields of Khuzestan, Iran, and potential health risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, B.; Tiryaki, O. Determination of fungicide residues in soil using QuEChERS coupled with LC-MS/MS, and environmental risk assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, Y.; Bunas, A.; Starodub, V. The Effect of Chemicals of Plant Protection Products on Soil Microbiocenoses. Sci. Horiz. 2021, 24, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martín, A.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S.; Soledad-Andrades, M.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J. Application of a biosorbent to soil: A potential method for controlling water pollution by pesticides. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 9192–9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischetti, C.; Monaci, E.; Casucci, C.; De Bernardi, A.; Cardinali, A. Adsorption and Degradation of Three Pesticides in a Vineyard Soil and in an Organic Biomix. Environments 2020, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Hernández, E.; Andrades, M.S.; Álvarez-Martín, A.; Pose-Juan, E.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S. Occurrence of pesticides and some of their degradation products in waters in a Spanish wine region. J. Hydrol. 2013, 486, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, S.; Ji, L.; Yu, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, F.; Yao, W.; Xie, Y. Zero-Background Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection of Cymoxanil Based on the Change of the Cyano Group afterUltraviolet Irradiation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, L.; Mendes, F.; Côrte-Real, M.; Rego, A.; Outeiro, T.F.; Chaves, S.R. A versatile yeast model identifies the pesticides cymoxanil and metalaxyl as risk factors for synucleinopathies. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yin, Y.; Gong, H.; Wang, H.; Ying, H.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Z. National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, K.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Tao, J.; Fan, L.; Raza, S.; Guggenberger, G.; Kuzyakov, Y. Acidification of European croplands by nitrogen fertilization: Consequences for carbonate losses, and soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalín-Pousa, V.; Conde-Cid, M.; Díaz-Raviña, M.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Fernández-Calviño, D. Acetamiprid retention in agricultural acid soils: Experimental data and prediction. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Prieto, S.; Romero-Estonllo, M. Soil physico-chemical changes half a century after drainage and cultivation of the former Antela lake (Galicia, NW Spain). Catena 2022, 217, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regasa, A.; Haile, W.; Abera, G. Effects of lime and vermicompost application on soil physicochemical properties and phosphorus availability in acid soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10390:2021; Soil, Treated Biowaste and Sludge-Determination of pH. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Sumner, M.E.; Miller, W.P. Cation exchange capacity and exchange coefficients. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; SSSA Book Series No. 5; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1201–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Coleman, N.T. The Measurement of Exchangeable Aluminum in Soils and Clays. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1960, 24, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, L.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Cela-Dablanca, R.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Arias-Estévez, M. Sorption of Antibiotics in Agricultural Soils as a Function of pH. Span. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 14, 12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Fate, Transport and Transformation Test Guidelines. OPPTS 835.1230. Adsorption/Desorption (Batch Equilibrium); United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 106: Adsorption—Desorption Using a Batch Equilibrium Method, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 1; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Couso, A.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Pateiro-Moure, M.; Garrido-Rodríguez, B.; Nóvoa-Muñoz, J.C.; Arias-Estévez, M. Adsorption and Desorption Behavior of Metalaxyl in Intensively Cultivated Acid Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7286–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Arias-Estévez, M. Adsorption/desorption and transport of sulfadiazine, sulfachloropyridazine, and sulfamethazine, in acid agricultural soils. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, C.H.; Smith, D.; Huitson, A. A general treatment and classification of the solute adsorption isotherm. I. Theoretical. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1974, 47, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet, R. Adsorption of Organic Chemicals in Soils. Environ. Health Perspect. 1989, 83, 145–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipov, U.; Kočárek, M.; Jursík, M.; Nikodem, A.; Borůvka, L. Adsorption and degradation behavior of six herbicides in different. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Campillo-Cora, C.; Pérez-Novo, C.; Fernández-Calviño, D. Retention of propiconazole and terbutryn on acid sandy-loam soils with different organic matter and Cu concentrations. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, A.A.; Holden, N.M. Adsorption and Desorption Isotherms of the Nonpolar Fungicide Chlorothalonil in a Range of Temperate Maritime Agricultural Soils. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2012, 223, 3975–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Vivas, C.S.; Martinez, M.J.; García-Santos, G.; Guerrero-Dallos, J.A. Adsorption-desorption and hysteresis phenomenon of tebuconazole in Colombian agricultural soils: Experimental assays and mathematical approaches. Chemosphere 2018, 190, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wu, T.; Lin, W.; Gu, X.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; Li, B. Adsorption–desorption and leaching behavior of benzovindiflupyr in different soil types. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 282, 116724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauchope, R.D.; Yeh, S.; Linders, J.B.H.J.; Kloskowski, R.; Tanaka, K.; Rubin, B.; Katayama, A.; Kördel, W.; Gerstl, Z.; Lane, M.; et al. Pesticide soil sorption parameters: Theory, measurement, uses, limitations and reliability. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doucette, W.J. Quantitative structure-activity relationships for predicting soil-sediment sorption coefficients for organic chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 1771–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, D.L. Environmental Soil Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, N.J. The description of sorption curves. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2008, 59, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayawei, N.; Ebelegi, A.N.; Wankasi, D. Modelling and Interpretation of Adsorption Isotherms. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 3039817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodešová, R.; Kočárek, M.; Kodeš, V.; Drábek, O.; Kozáka, J.; Hejtmánková, K. Pesticide adsorption in relation to soil properties and soil type distribution in regional scale. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ge, Q.; Mei, J.; Cui, Y.; Xue, Y.; Yu, Y.; Fang, H. Adsorption and Desorption of Carbendazim and Thiamethoxam in Five Different Agricultural Soils. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 102, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patakioutas, G.; Albanis, T.A. Adsorption–desorption studies of alachlor, metolachlor, EPTC, chlorothalonil andpirimiphos-methyl in contrasting soils. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.; Torrente, A.C.; López, E.; Soto, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Adsorption-Desorption Dynamics of Cyprodinil and Fludioxonil in Vineyard Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5675–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoratos, A.; Fois, C.; Danias, P.; Likudis, Z. Investigation of the Soil Sorption of Neutral and Basic Pesticides. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.; Paradelo, M.; López, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Influence of pH and Soil Copper on Adsorption of Metalaxyl and Penconazole by the Surface Layer of Vineyard Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8155–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rütters, H.; Höllrigl-Rosta, A.; Kreuzig, R.; Bahadir, M. Sorption Behavior of Prochloraz in Different Soils. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1999, 47, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorstensen, C.W.; Lode, O.; Eklo, O.M.; Christiansen, A. Sorption of Bentazone, Dichlorprop, MCPA, and Propiconazolein Reference Soils from Norway. J. Environ. Qual. 2001, 30, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cao, D.; Shi, L.; He, S.; Li, X.; Fang, H.; Yu, Y. Competitive Adsorption and Mobility of Propiconazole and Difenoconazole on Five Different Soils. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 105, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallé, R.; Dousset, S.; Billet, D.; Benoit, M. Sorption of selected pesticides on soils, sediment and straw from a constructed agricultural drainage ditch or pond. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 4895–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouad, M.R.; Abdel-Raheem, S.A.A. An overview on the fate and behavior of imidacloprid in agricultural environments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 61345–61355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullagurala, V.L.R.; Rawat, S.; Adisa, I.O.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Plant uptake and translocation of contaminants of emerging concern in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriuso, E.; Laird, D.A.; Koskinen, W.C.; Dowdy, R.H. Atrazine desorption from smectites. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Weber, W.J. A distributed Reactivity Model for Sorption by Soils and Sediments. 10. Relationships between Desorption, Hysteresis, and the Chemical Characteristics of Organic Domains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 2562–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Nóvoa-Muñoz, J.C.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E. Experimental data and modeling for sulfachloropyridazine and sulfamethazine adsorption/desorption on agricultural acid soils. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2019, 288, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglöf, T.; Van Dung, T.; Kylin, H.; Nilsson, I. Carbendazim sorption–desorption in Vietnamese soils. Chemosphere 2002, 48, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszko, T. Effect of pH on the adsorption of carbendazim in Polish mineral soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 435–436, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondar, D.; López, R.; Antelo, J.; Fiol, S.; Arce, F. Effect of organic matter and pH on the adsorption of metalaxyl and penconazole by soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkiedje, A.; Spiteller, M. Sorptive behavior of the phenylamide fungicides, mefenoxam and metalaxyl, and their acid metabolite in typical Cameroonian and German soils. Chemosphere 2002, 49, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campan, P.; Samouelian, A.; Richard, A.; Négro, S.; Lagacherie, M.; Voltz, M. Pedological factors affecting pesticide retention in a series of tropical volcanic ash soils in the French West Indies. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 38, e00830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J. Reaction of Anions and Cations with Variable-Charge Soils. Adv. Agron. 1986, 38, 183–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Novo, C.; Bermúdez-Couso, A.; López-PEriago, E.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Arias-Estévez, M. The effect of Phosphate on the Sorption of Copper by Acid Soils. Geoderma 2009, 150, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Ferreira-Coelho, G.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E. Single and simultaneous adsorption of three sulfonamides in agricultural soils: Effects of pH and organic matter content. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Esmorís, C.; Conde-Cid, M.; Ferreira-Coelho, G.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Arias-Estévez, M. Adsorption/desorption of sulfamethoxypyridazine and enrofloxacin in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Brown, C.D. Prediction of the Adsorption of Ionizable Pesticides in Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2312–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Fostier, A.H.; Pereira, L.A.; Dionisio, A.C.; Ferreira, F.O.; Doretto, K.M.; Peruchi, L.M.; Viera, A.; Neto, O.F.O.; Bosco, S.M.D.; et al. Sorption behaviors of antimicrobial and antiparasitic veterinary drugs on subtropical soils. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E. Estimation of adsorption/desorption Freundlich’s affinity coefficients for oxytetracycline and chlortetracycline from soil properties: Experimental data and pedotransfer functions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil | pHW | pHKCl | N | TOC | Sand | Silt | Clay | Texture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||||||

| 1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 64 ± 5 | 19 ± 2 | 17 ± 1 | Sandy loam |

| 2 | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 41 ± 2 | 26 ± 1 | 34 ± 1 | Clay loam |

| 3 | 4.6 ± 0.0 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 58 ± 5 | 23 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 | Sandy loam |

| 4 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.0 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 57 ± 3 | 20 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | Sandy clay loam |

| 5 | 4.5 ± 0.0 | 3.1 ± 0.0 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 45 ± 1 | 33 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | Loam |

| 6 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 53 ± 4 | 26 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | Sandy clay loam |

| 7 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 52 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 | 19 ± 1 | Sandy loam |

| 8 | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 3.3 ± 0.0 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 46 ± 2 | 32 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | Loam |

| 9 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.0 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 51 ± 3 | 28 ± 2 | 22 ± 1 | Sandy clay loam |

| 10 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 48 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 22 ± 1 | Loam |

| 11 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 56 ± 6 | 23 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | Sandy clay loam |

| 12 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 47 ± 4 | 31 ± 3 | 22 ± 2 | Loam |

| Soil | Cae | Mge | Ke | Nae | Ale | eCEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmolc kg−1 | ||||||

| 1 | 1.79 ± 0.11 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 4.46 ± 0.19 |

| 2 | 5.91 ± 0.23 | 1.68 ± 0.13 | 2.96 ± 0.14 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 11.64 ± 0.31 |

| 3 | 1.77 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 4.61 ± 0.13 |

| 4 | 2.76 ± 0.14 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 1.43 ± 0.10 | 6.51 ± 0.19 |

| 5 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.08 |

| 6 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.09 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 2.05 ± 0.13 |

| 7 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 1.68 ± 0.11 |

| 8 | 0.70 ± 0.09 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 2.24 ± 0.12 |

| 9 | 0.45 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 1.7 ± 0.12 |

| 10 | 1.67 ± 0.13 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 3.53 ± 0.19 |

| 11 | 1.28 ± 0.09 | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 2.95 ± 0.14 |

| 12 | 2.16 ± 0.07 | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 1.42 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 4.51 ± 0.13 |

| Soil | Linear | Freundlich | %Ads100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd(ads) | R2 | KF(ads) | 1/n(ads) | R2 | ||

| 1 | 0.93 ± 0.13 | 0.912 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 1.68 ± 0.26 | 0.975 | 28.9 |

| 2 | 1.62 ± 0.03 | 0.998 | 3.38 ± 0.72 | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 0.993 | 40.9 |

| 3 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.997 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 0.999 | 25.9 |

| 4 | 1.35 ± 0.08 | 0.984 | 2.30 ± 0.61 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.990 | 35.4 |

| 5 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.981 | 1.53 ± 0.53 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.984 | 27.2 |

| 6 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.979 | 0.70 ± 0.30 | 1.05 ± 0.11 | 0.984 | 26.2 |

| 7 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 0.978 | 0.34 ± 0.11 | 1.26 ± 0.08 | 0.995 | 28.7 |

| 8 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.990 | 1.51 ± 0.20 | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.997 | 19.4 |

| 9 | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 0.947 | 1.96 ± 0.62 | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.977 | 18.7 |

| 10 | 1.42 ± 0.34 | 0.766 | 10.79 ± 3.96 | 0.53 ± 0.10 | 0.921 | 37.4 |

| 11 | 4.46 ± 0.29 | 0.983 | 12.60 ± 0.84 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.998 | 65.9 |

| 12 | 4.40 ± 0.24 | 0.986 | 12.96 ± 1.92 | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 0.993 | 65.3 |

| Fungicide | pHW | TOC | Kd(ads) | KF(ads) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoxystrobin | 4.8–8.6 | 0.0–5.0 | 2.4–18.5 | [54] | |

| Benzovindiflupir | 4.5–8.7 | 0.2–2.6 | 1.5–16.7 | 2.3–17.9 | [48] |

| Carbendazin | 5.2–7.4 | 0.3–2.9 | 1.5–19.5 | [55] | |

| Chlorothalonil | 5.9–6.2 | 2.7–4.7 | 34.2–101.6 | 17.7–78.2 | [46] |

| Chlorothalonil | 6.2–7.9 | 0.3–6.1 | 96.3–1356.9 | [56] | |

| Cymoxanil | 4.1–5.9 | 1.2–5.3 | 0.6–4.4 | 0.1–13.0 | This work |

| Cymoxanil | 7.5–7.8 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.3–1.0 | [23] |

| Cymoxanil | 8.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | [24] | |

| Cyprodinil | 5.3–7.4 | 2.7–4.9 | 54.0–110.0 | [57] | |

| Difenoconazole | 4.1–8.4 | 0.8–3.8 | 14.8–98.9 | [58] | |

| Fludioxonil | 5.3–7.4 | 2.7–4.9 | 62.0–213.0 | [57] | |

| Metalaxyl | 4.3–5.7 | 1.1–16.6 | 0.0–3.1 | 0.2–6.3 | [40] |

| Metalaxyl | 5.3–7.4 | 2.7–4.9 | 1.0–2.3 | [59] | |

| Penconazole | 5.3–7.4 | 2.7–4.9 | 41.7–94.5 | [59] | |

| Prochloraz | 5.4–8.9 | 0.3–6.1 | 10.0–648.6 | [58] | |

| Prochloraz | 5.3–7.8 | 0.5–4.4 | 56.0–552.0 | [60] | |

| Propiconazole | 4.5–5.2 | 0.3–4.8 | 4.6–28.9 | 8.3–69.4 | [45] |

| Propiconazole | 2.9–6.3 | 1.4–37.7 | 27.0–1277.0 | [61] | |

| Propiconazole | 4.1–8.4 | 0.8–3.8 | 2.9–28.7 | [62] | |

| Quinoxyfen | 5.4–8.9 | 0.3–6.1 | 7.9–182.8 | [58] | |

| Tebuconazole | 5.1–6.0 | 0.7–13.0 | 7.9–289.2 | 8.1–283.4 | [47] |

| Tebuconazole | 7.5–7.9 | 1.2–1.5 | 5.8–10.9 | [63] | |

| Triadimefon | 5.4–8.9 | 0.3–6.1 | 5.9–79.6 | [58] |

| Soil | Linear | Freundlich | %Des100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd(des) | R2 | KF(des) | 1/n(des) | R2 | ||

| 1 | 15.27 ± 1.03 | 0.978 | 18.01 ± 1.47 | 0.88 ± 0.07 | 0.988 | 14.1 |

| 2 | 47.25 ± 3.68 | 0.970 | 43.25 ± 2.77 | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 0.981 | 5.0 |

| 3 | 14.51 ± 1.34 | 0.959 | 15.85 ± 1.98 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 0.971 | 15.0 |

| 4 | 41.01 ± 3.06 | 0.973 | 38.59 ± 2.55 | 1.16 ± 0.14 | 0.983 | 5.4 |

| 5 | 22.19 ± 1.65 | 0.973 | 23.93 ± 1.78 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 0.982 | 10.5 |

| 6 | 8.59 ± 0.79 | 0.959 | 11.53 ± 1.47 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.979 | 21.7 |

| 7 | 10.79 ± 0.51 | 0.989 | 8.57 ± 0.86 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 0.995 | 18.4 |

| 8 | 12.91 ± 1.66 | 0.922 | 10.07 ± 1.97 | 1.18 ± 0.21 | 0.937 | 17.5 |

| 9 | 4.67 ± 0.27 | 0.983 | 6.01 ± 1.00 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | 0.978 | 32.6 |

| 10 | 49.33 ± 4.92 | 0.952 | 50.58 ± 3.58 | 0.94 ± 0.14 | 0.963 | 5.1 |

| 11 | 78.68 ± 5.74 | 0.974 | 83.44 ± 4.80 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 0.978 | 2.8 |

| 12 | 87.80 ± 12.78 | 0.902 | 85.05 ± 9.41 | 1.11 ± 0.29 | 0.924 | 2.4 |

| Adsorption | Desorption | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd(ads) | KF(ads) | Kd(des) | KF(des) | |

| pHW | 0.844 ** | 0.920 ** | 0.895 ** | 0.920 ** |

| pHKCl | 0.503 | 0.467 | 0.636 * | 0.632 * |

| Cae | 0.200 | 0.148 | 0.409 | 0.363 |

| Mge | 0.272 | 0.241 | 0.469 | 0.424 |

| Ke | 0.177 | 0.079 | 0.357 | 0.306 |

| Nae | −0.051 | −0.115 | 0.164 | 0.119 |

| Ale | −0.343 | −0.479 | −0.229 | −0.255 |

| eCEC | 0.139 | 0.062 | 0.348 | 0.299 |

| N | 0.077 | 0.02 | 0.280 | 0.220 |

| TOC | 0.057 | 0.014 | 0.263 | 0.203 |

| Sand | −0.036 | −0.198 | −0.183 | −0.13 |

| Silt | 0.017 | 0.217 | 0.050 | 0.022 |

| Clay | 0.038 | 0.067 | 0.241 | 0.188 |

| Similar OM and Clay Contents, Different pHW (SpH soils) (n = 7) | Similar pHW, Different OM and Clay Contents (SOM,Clay soils) (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Desorption | Adsorption | Desorption | |||||

| Kd(ads) | KF(ads) | Kd(des) | KF(des) | Kd(ads) | KF(ads) | Kd(des) | KF(des) | |

| pHW | 0.879** | 0.959 ** | 0.943 ** | 0.950 ** | 0.892 ** | 0.383 | 0.832 * | 0.833 * |

| pHKCl | 0.735 | 0.827 * | 0.784 * | 0.792 * | 0.732 | 0.195 | 0.607 | 0.603 |

| Cae | 0.735 | 0.888 ** | 0.842 * | 0.820 * | 0.892 ** | 0.642 | 0.832 * | 0.811 * |

| Mge | 0.758 * | 0.904 ** | 0.876 ** | 0.852 * | 0.854 * | 0.650 | 0.784 * | 0.762 * |

| Ke | 0.774 * | 0.847 * | 0.871 * | 0.832 * | 0.858 * | 0.583 | 0.795 * | 0.780 * |

| Nae | 0.245 | 0.574 | 0.449 | 0.424 | 0.893 ** | 0.577 | 0.837 * | 0.819 * |

| Ale | −0.736 | −0.894 ** | −0.826 * | −0.822 * | 0.440 | 0.190 | 0.528 | 0.522 |

| eCEC | 0.744 | 0.882 ** | 0.858 * | 0.828 * | 0.902 ** | 0.628 | 0.852 * | 0.832 * |

| N | 0.471 | 0.417 | 0.542 | 0.501 | 0.872 * | 0.888 ** | 0.867 * | 0.838 * |

| TOC | 0.221 | 0.163 | 0.292 | 0.265 | 0.858 * | 0.919 ** | 0.868 * | 0.837 * |

| Sand | 0.377 | 0.260 | 0.203 | 0.263 | −0.352 | −0.750 | −0.385 | −0.362 |

| Silt | −0.320 | −0.216 | −0.148 | −0.209 | −0.212 | 0.278 | −0.146 | −0.149 |

| Clay | −0.677 | −0.500 | −0.523 | −0.564 | 0.748 | 0.899 ** | 0.735 | 0.702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Conde-Cid, M.; Gómez-Armesto, A.; Lalín-Pousa, V.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Fernández-Calviño, D. Adsorption/Desorption Behaviour of the Fungicide Cymoxanil in Acidic Agricultural Soils. Agriculture 2026, 16, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010041

Conde-Cid M, Gómez-Armesto A, Lalín-Pousa V, Arias-Estévez M, Fernández-Calviño D. Adsorption/Desorption Behaviour of the Fungicide Cymoxanil in Acidic Agricultural Soils. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleConde-Cid, Manuel, Antía Gómez-Armesto, Vanesa Lalín-Pousa, Manuel Arias-Estévez, and David Fernández-Calviño. 2026. "Adsorption/Desorption Behaviour of the Fungicide Cymoxanil in Acidic Agricultural Soils" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010041

APA StyleConde-Cid, M., Gómez-Armesto, A., Lalín-Pousa, V., Arias-Estévez, M., & Fernández-Calviño, D. (2026). Adsorption/Desorption Behaviour of the Fungicide Cymoxanil in Acidic Agricultural Soils. Agriculture, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010041