Climatic Variability and Adaptive Zoning of Maize Cultivation in High-Latitude Cold Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

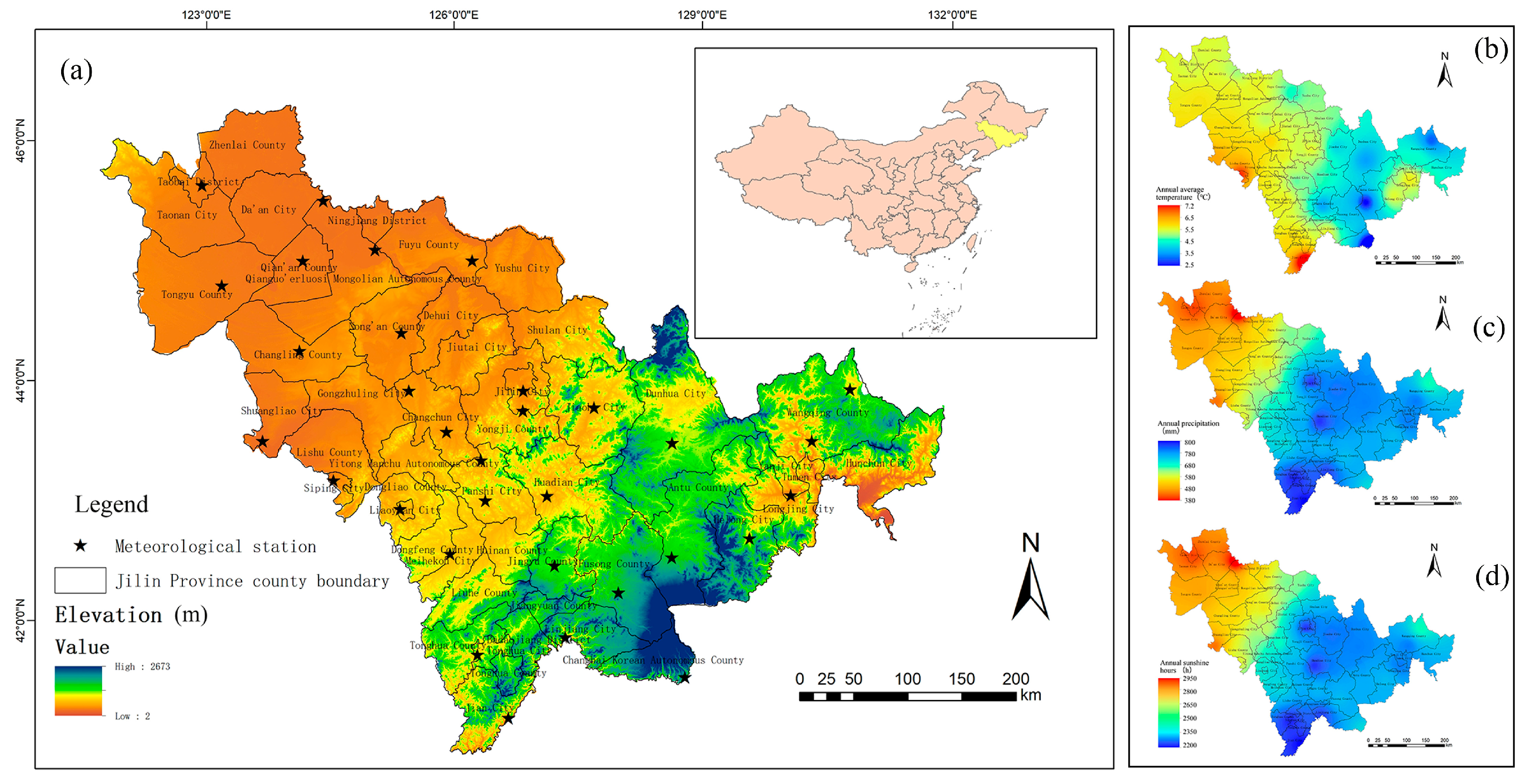

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Inverse Distance Weighted Interpolation Method

2.2.2. M-K Mutation Test Method

2.2.3. Trend Analysis of Meteorological Variables

2.2.4. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method

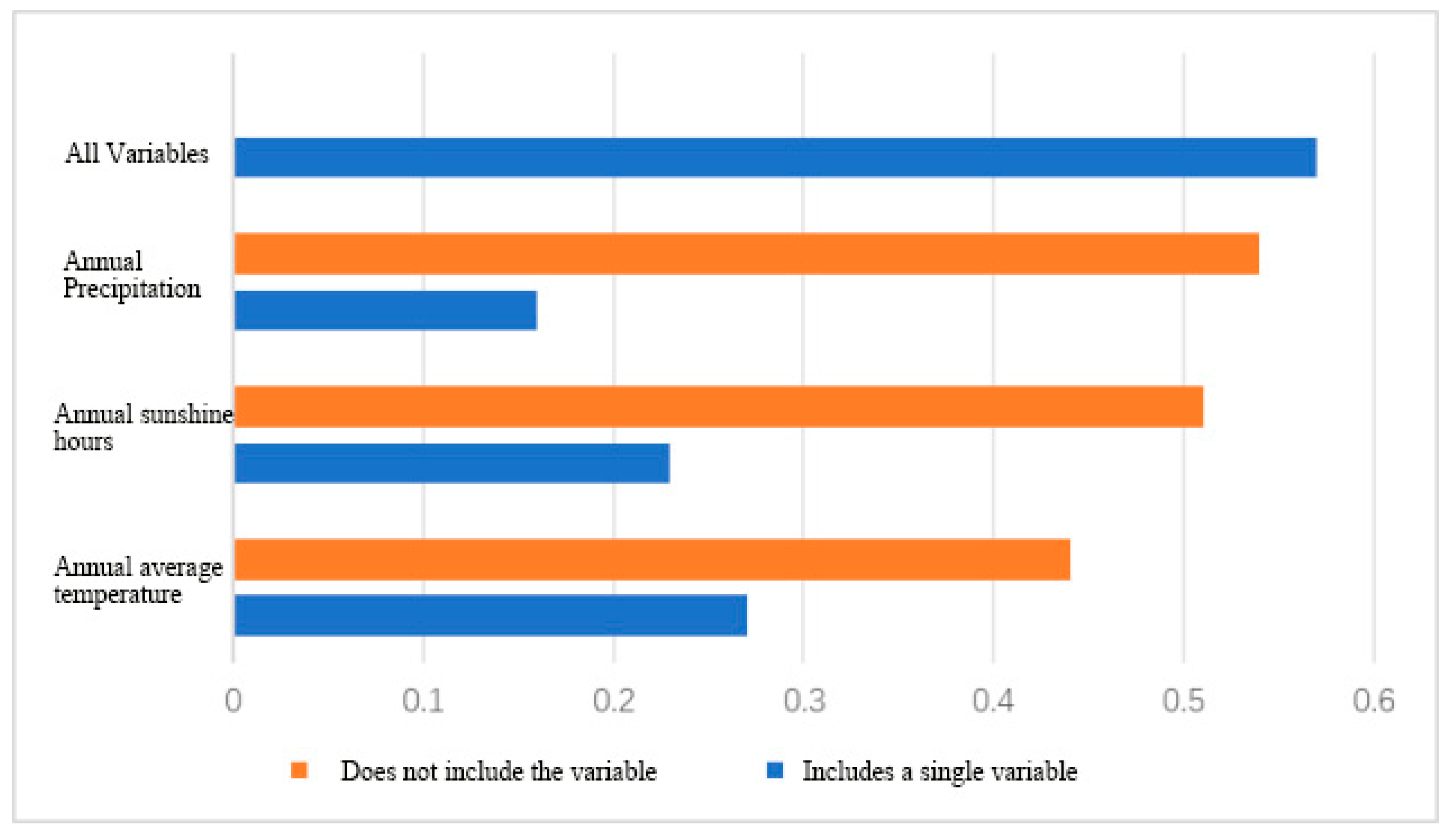

2.3. Data Sources

3. Results

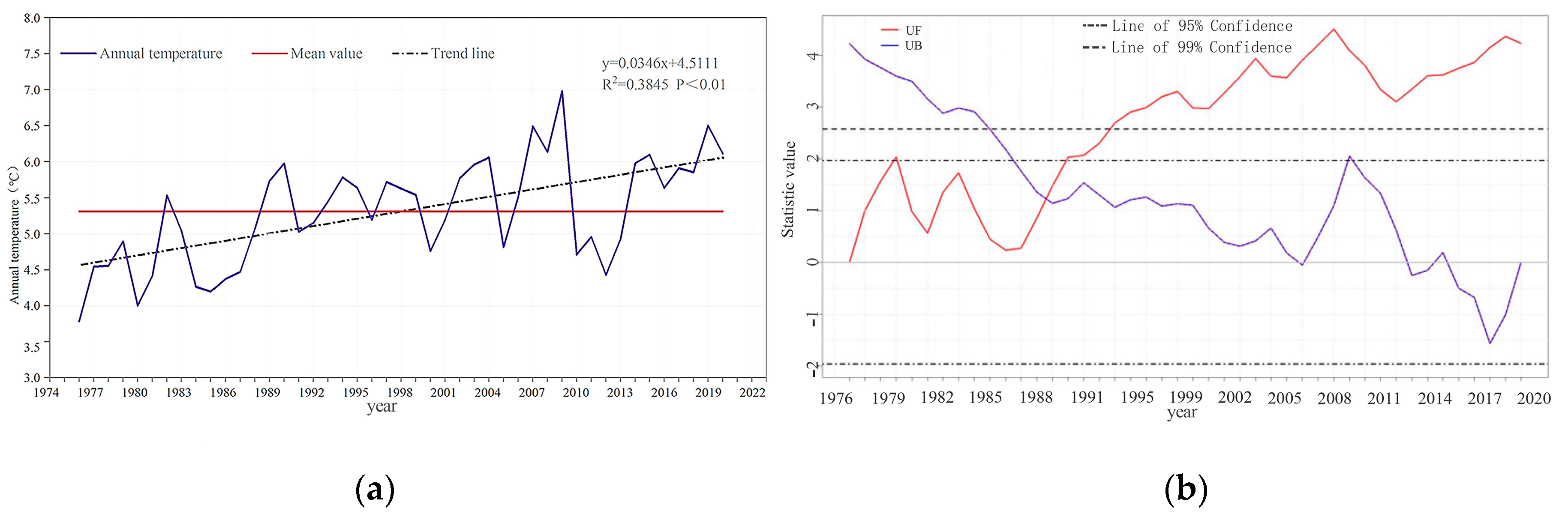

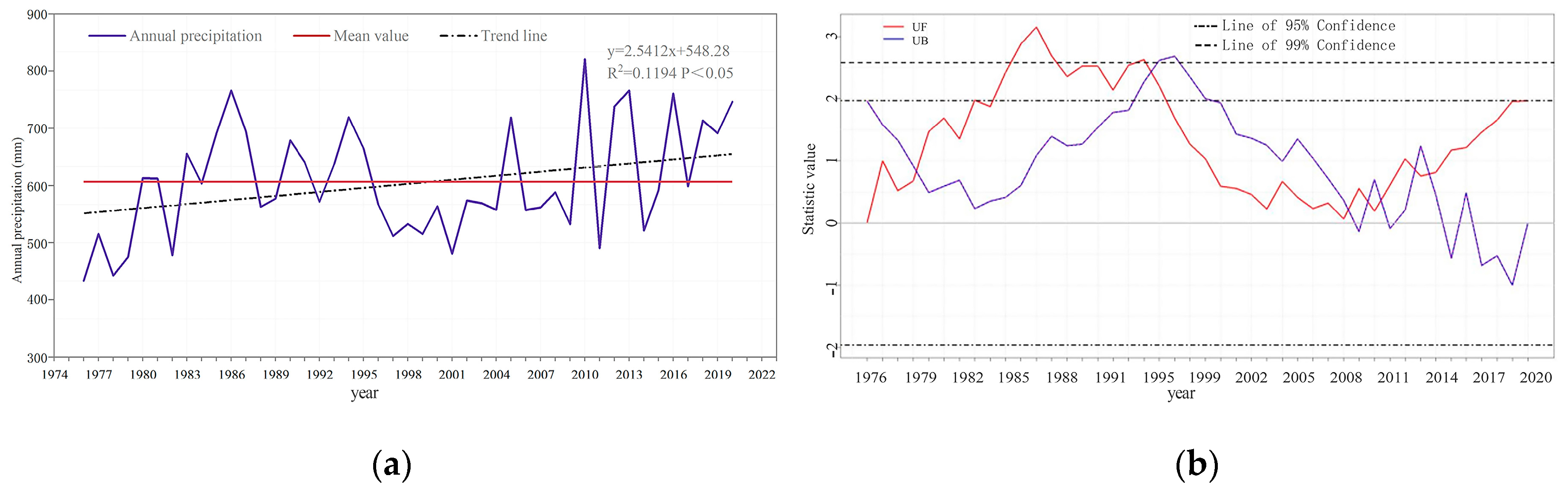

3.1. Temporal Variation Characteristics and Abrupt Change Analysis of Major Climatic Factors in Jilin Province

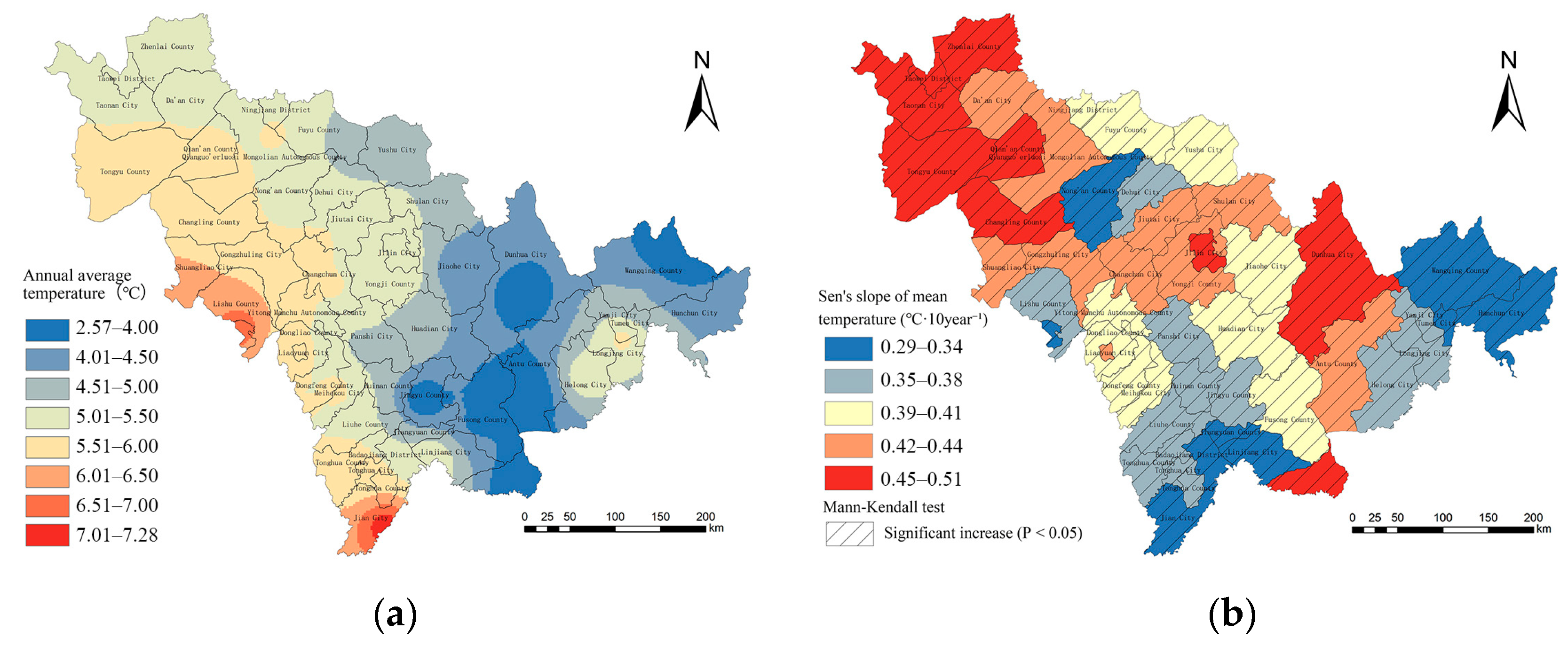

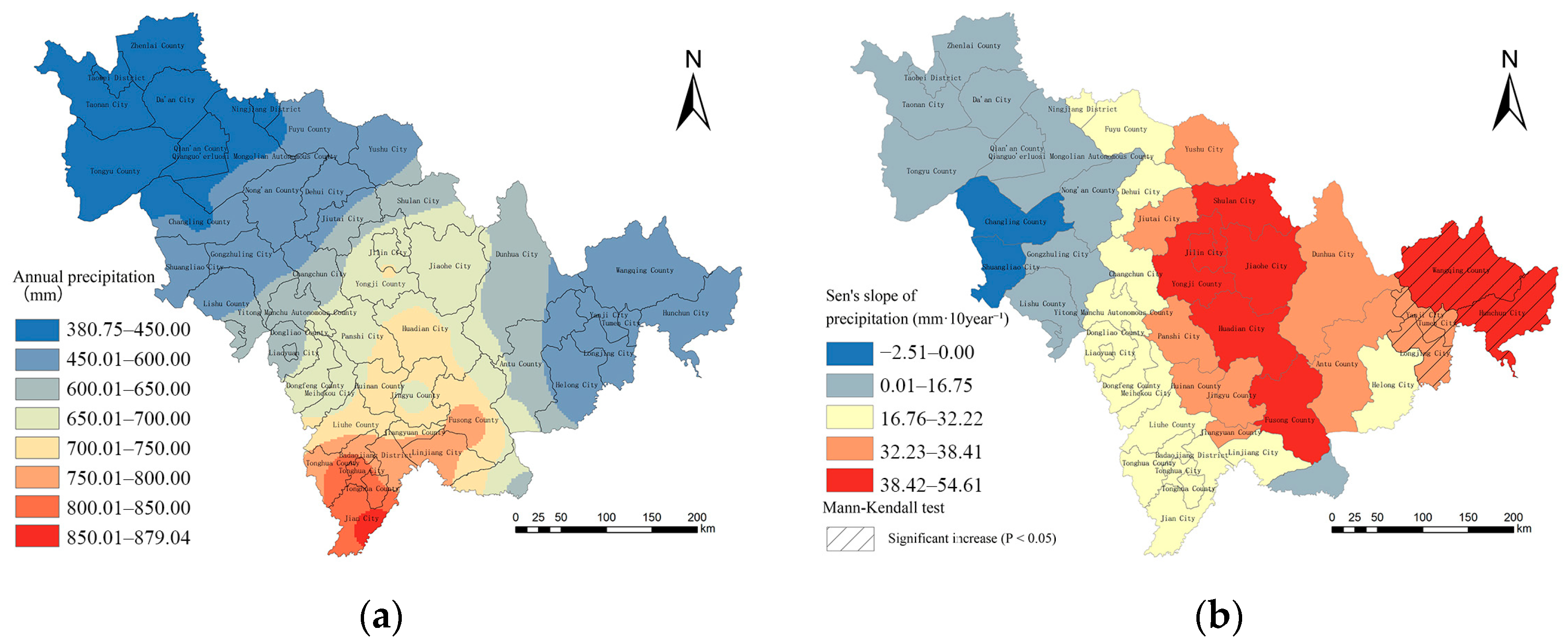

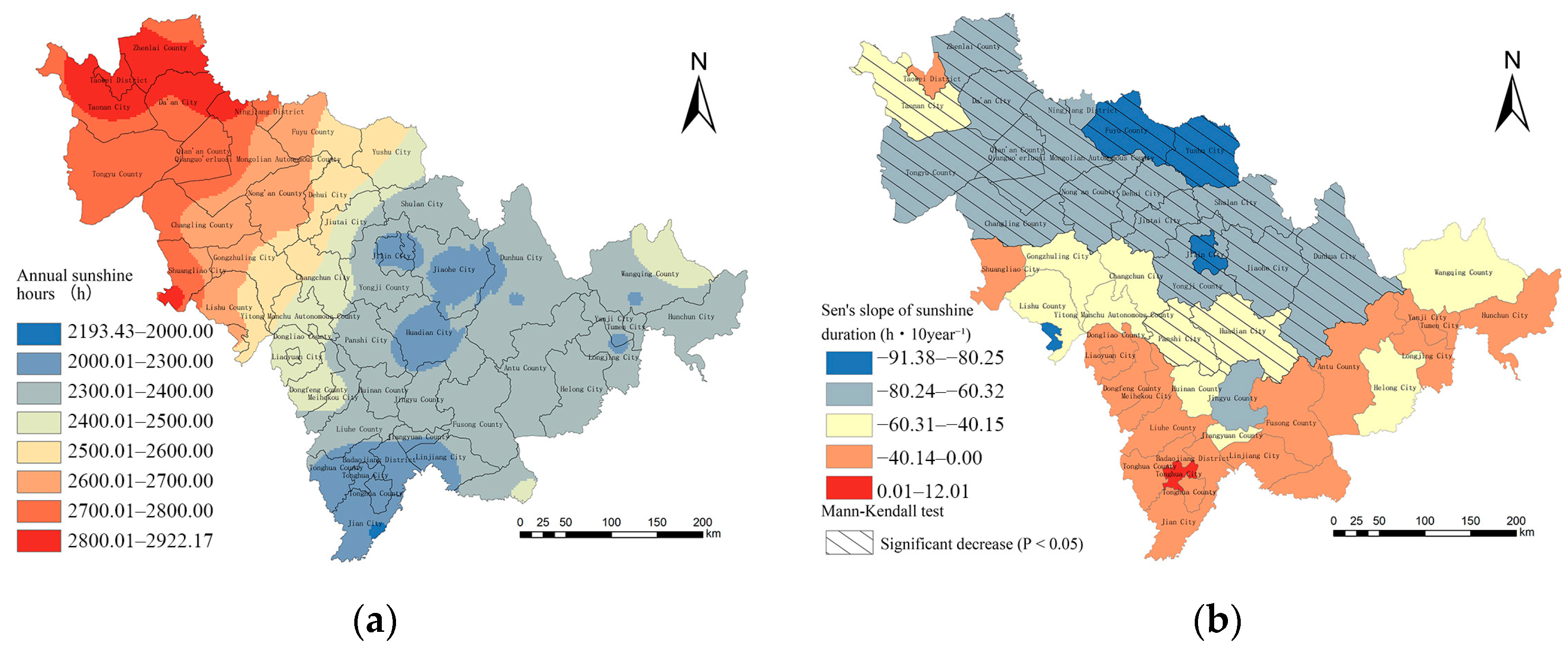

3.2. Spatial Variation Characteristics of Main Climatic Factors in Jilin Province

3.3. Maize Suitability Zoning Before and After Mutation in Jilin Province

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Climatic Factors Affecting Maize Suitability

4.2. Climate Suitability Zoning for Maize Cultivation

4.3. Uncertainty Analysis

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Main Research Conclusions

5.2. Suggestions for Maize Cultivation Optimization

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- You, N.; Till, J.; Lobell, D.B.; Zhu, P.; West, P.C.; Kong, H.; Li, W.; Sprenger, M.; Villoria, N.B.; Li, P.; et al. Climate-driven global cropland changes and consequent feedbacks. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Yin, D. Impacts of integrated meteorological and agricultural drought on global maize yields. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook-2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Gong, D.; Gong, W. Impacts of climate change on maize production and countermeasures in Northeast China. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2020, 10, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Cabral, N.Y.Z.; Kumar, L.; Shabani, F. Global alterations in areas of suitability for maize production from climate change and using a mechanistic species distribution model (CLIMEX). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frich, P.; Alexander, L.V.; Della-Marta, P.; Gleason, B.; Haylock, M.; Tank, A.M.G.K.; Peterson, T. Observed coherent changes in climatic extremes during the second half of the twentieth century. Clim. Res. 2002, 19, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, Z. Impacts of climate change as a function of global mean temperature: Maize productivity and water use in China. Clim. Change 2010, 105, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, T.; Chen, Q.; Qin, Y.; Ge, Q. Climate-associated major food crops production change under multi-scenario in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 151393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M. A Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Meteorological, Soil, and Field Management Factors on Maize Nitrogen Use Efficiency; Water Resources and Civil Engineering College, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University: Hohhot, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.-A. Global Synthesis of Drought Effects on Maize and Wheat Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Field, C.B. Global scale climate–crop yield relationships and the impacts of recent warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2007, 2, 014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, E.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying the effects of climate trends in the past 43 years (1961–2003) on crop growth and water demand in the North China Plain. Clim. Change 2009, 100, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, K.; Schnitkey, G.D.; DeLucia, E.; Peng, B. Excessive rainfall leads to maize yield loss of a comparable magnitude to extreme drought in the United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2325–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Król-Badziak, A.; Kozyra, J.; Rozakis, S. Assessment of Suitability Area for Maize Production in Poland Related to the Climate Change and Water Stress. Sustainability 2024, 16, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojara, M.A.; Yunsheng, L.; Ongoma, V.; Mumo, L.; Akodi, D.; Ayugi, B.; Ogwang, B.A. Projected changes in East African climate and its impacts on climatic suitability of maize production areas by the mid-twenty-first century. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, F. Growing sensitivity of maize to water scarcity under climate change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Menefee, D.; Cui, S.; Rajan, N.; Fletcher, A. Assessing the impacts of projected climate changes on maize (Zea mays) productivity using crop models and climate scenario simulation. Crop Pasture Sci. 2021, 72, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, K.; Bi, S.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Alatrach, B.; Srivastava, A.K.; Al-Mutiry, M.; Bal, S.K.; Chandran, M.A.S.; Mohammed, S. Modeling the impacts of projected climate change on wheat crop suitability in semi-arid regions using the AHP-based weighted climatic suitability index and CMIP6. Geosci. Lett. 2023, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; Boori, M.S.; Shi, W.; Valiev, A.; Kupriyanov, A. Agricultural land suitability assessment for sustainable development using remote sensing techniques with analytic hierarchy process. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 32, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, X. Spatial patterns of yield-based cropping suitability and its driving factors in the three main maize-growing regions in China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalew, S.G.; van Griensven, A.; Mul, M.L.; van der Zaag, P. Land suitability analysis for agriculture in the Abbay basin using remote sensing, GIS and AHP techniques. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, C.; Yu, C. Ecological suitability evaluation and regionalization of maize in Heilongjiang Province. J. Maize Sci. 2009, 17, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Zhu, D.; Yang, Y. Assessment of environment lodging stress for maize using fuzzy synthetic evaluation. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 54, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, P.Y.; Smith, C.A.S.; Brierley, J.A.; Schut, P.H.; Neilsen, D.; Kenney, E.A. The use of the land suitability rating system to assess climate change impacts on corn production in the lower Fraser Valley of British Columbia. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2016, 96, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-H.; Sheng, K.; Wang, Y.-H.; Dong, Y.-Q.; Jiang, Z.-K.; Sun, J.-S. Influence of furrow irrigation regime on the yield and water consumption indicators of winter wheat based on a multi-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation. Open Life Sci. 2022, 17, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hong, T.; Cai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z. Determination of amount of irrigation and nitrogen for comprehensive growth of greenhouse cucumber based on multi-level fuzzy evaluation. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Z.; Xing, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, M. Dynamic evaluation of cropland degradation risk by combining multi-temporal remote sensing and geographical data in the Black Soil Region of Jilin Province, China. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 154, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Yu, L.; Yu, E.; Li, R.; Cai, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, X. Improving the simulation of maize growth using WRF-Crop model based on data assimilation and local maize characteristics. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 365, 110478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Schlenker, W.; Costa-Roberts, J. Climate Trends and Global Crop Production Since 1980. Science 2011, 333, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Luo, N.; Meng, Q.; Wang, P. Dissecting the critical stage in the response of maize kernel set to individual and combined drought and heat stress around flowering. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 179, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.J.; Harrison, P.A.; Olesen, J.E.; Parry, M.L. The effects of climate change on land suitability of grain maize, winter wheat and cauliflower in Europe. Eur. J. Agron. 1993, 2, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilin Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Jilin Statistical Yearbook. 2024. Available online: http://tjj.jl.gov.cn/tjsj/tjnj/2024/enter.htm (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.Z.; Yu, D.S.; Xu, S.X.; Warner, E.D.; Wang, H.J.; Sun, W.X.; Zhao, Y.C.; Gong, Z.T. Cross-reference for relating Genetic Soil Classification of China with WRB at different scales. Geoderma 2010, 155, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Chang, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, J. Spatial-temporal variations of ecological vulnerability in Jilin Province (China), 2000 to 2018. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-W.; Liu, C.-W. Estimation of the spatial rainfall distribution using inverse distance weighting (IDW) in the middle of Taiwan. Paddy Water Environ. 2012, 10, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Yang, G.; Yao, J.; Liao, N. Impacts of climate change and human activities on water resources in the Ebinur Lake Basin, Northwest China. J. Arid Land 2021, 13, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Rasmussen, A.; Porter, J.R. Temperatures and the growth and development of maize and rice: A review. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 20, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyama, D.; Mighty, M.; Sim, S.; Koti, F. A spatial assessment of land suitability for maize farming in Kenya. Geocarto Int. 2019, 36, 1378–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Wang, L.; Luo, X.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, G. Evaluation of suitability areas for maize in China based on GIS and its variation trend on the future climate Condition. In Ecosystem Assessment and Fuzzy Systems Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pilevar, A.R.; Matinfar, H.R.; Sohrabi, A.; Sarmadian, F. Integrated fuzzy, AHP and GIS techniques for land suitability assessment in semi-arid regions for wheat and maize farming. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 110, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król-Badziak, A.; Kozyra, J.; Rozakis, S. Evaluation of Climate Suitability for Maize Production in Poland under Climate Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, X.; Jin, X. Analysis of climate change characteristics in Jilin Province from 1991 to 2022 and its impact on agriculture. J. Agric. Catastrophol. 2023, 13, 195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Guo, Y. Impacts of Meteorological Disasters on Maize Cultivation in Jilin Province and Response Strategies. South Agric. 2022, 16, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, M.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Kausar, A.; Saleem, S.; Anwar, S.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Growth and physio-biochemical responses of maize (Zea mays L.) to drought and heat stresses. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2020, 155, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Kar, I.; Yadav, A.; Sahu, A. Exploring Waterlogging Challenges, Causes and Mitigating Strategies in Maize (Zea mays L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Lv, S.; Wang, J.; Dai, S. Variations in the potential climatic suitability distribution patterns and grain yields for spring maize in Northeast China under climate change. Clim. Change 2016, 137, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ren, B.; Zhao, B.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J. The environment, especially the minimum temperature, affects summer maize grain yield by regulating ear differentiation and grain development. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 2227–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. GIS-based climatic suitability regionalization for spring maize in Tuoli County. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. Technol. 2018, 4, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhou, G. The climatic suitability for maize cultivation in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 57, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yao, X.; Hu, S. Climate suitability regionalization of double-cropping silage maize in Hebei Province based on effective accumulated temperature. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2025, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liang, H.; Li, Y. Impacts of climate warming on the development stages and planting distribution of spring maize in the three provinces of Northeast China. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, E. The effects of past climate change on the northern limits of maize planting in Northeast China. Clim. Change 2012, 117, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhou, G.; Sui, X. Decadal dynamics of potential spring maize planting distribution in China from 1961 to 2010. Chin. J. Ecol. 2012, 57, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelRahman, M.A.E.; Yossif, T.M.H.; Metwaly, M.M. Enhancing land suitability assessment through integration of AHP and GIS-based for efficient agricultural planning in arid regions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Lin, X.; Sassenrath, G.F.; Ciampitti, I.; Gowda, P.; Ye, Q.; Yang, X. Dryland maize yield potentials and constraints: A case study in western Kansas. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 11, e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, T.C.; Pulido, D.J.; Fenton, T.E.; Colvin, T.S.; Karlen, D.L.; Jaynes, D.B.; Meek, D.W. Relationship of Corn and Soybean Yield to Soil and Terrain Properties. Agron. J. 2004, 96, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tao, F.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H. The effect of terrain factors on rice production: A case study in Hunan Province. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Lei, G. Long-term effects of soil erosion on dryland crop yields in the Songnen Plain, Northeast China. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Norm | Annual Average Temperature (°C) | Annual Sunshine Hours (h) | Annual Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level I suitable | 6.5~7.5 | 2000~2300 | 450~600 |

| Level II suitable | 5.5~6.5 | 2300~2500 | 600~700 |

| Level III suitable | 4~5.5 | 2500~2800 | 0~450, 700~850 |

| Level IV suitable | <4 | >2800 | >850 |

| Norm | Area Before Mutation (km2) | Total Area Ratio (%) | Area After Mutation (km2) | Total Area Ratio (%) | p-Value | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I suitable | 44,449.21 | 23.27% | 44,638.51 | 23.37% | 0.001 *** | 3.696 |

| Level II suitable | 37,473.91 | 19.62% | 48,895.02 | 25.60% | 0.010 ** | 3.033 |

| Level III suitable | 81,773.95 | 42.81% | 78,020.88 | 40.85% | 0.003 ** | 3.398 |

| Level IV suitable | 27,316.54 | 14.30% | 19,459.21 | 10.19% | 0.221 | 1.399 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Fang, N.; Jin, S.; Zhai, C. Climatic Variability and Adaptive Zoning of Maize Cultivation in High-Latitude Cold Regions. Agriculture 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010040

Huang J, Fang N, Jin S, Zhai C. Climatic Variability and Adaptive Zoning of Maize Cultivation in High-Latitude Cold Regions. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jia, Ning Fang, Shiran Jin, and Chang Zhai. 2026. "Climatic Variability and Adaptive Zoning of Maize Cultivation in High-Latitude Cold Regions" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010040

APA StyleHuang, J., Fang, N., Jin, S., & Zhai, C. (2026). Climatic Variability and Adaptive Zoning of Maize Cultivation in High-Latitude Cold Regions. Agriculture, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010040