Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanisms of Cold Stress in Japonica Rice at the Booting Stage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Cultivation

2.2. Determination of Antioxidant-Related Enzyme Activities and Substances

2.3. Widely Targeted Metabolome Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Transcriptome Sequencing and Differential Expression Gene Analysis

2.5. Construction of Co-Expression Networks and Mining of Candidate Hub Genes

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Analysis

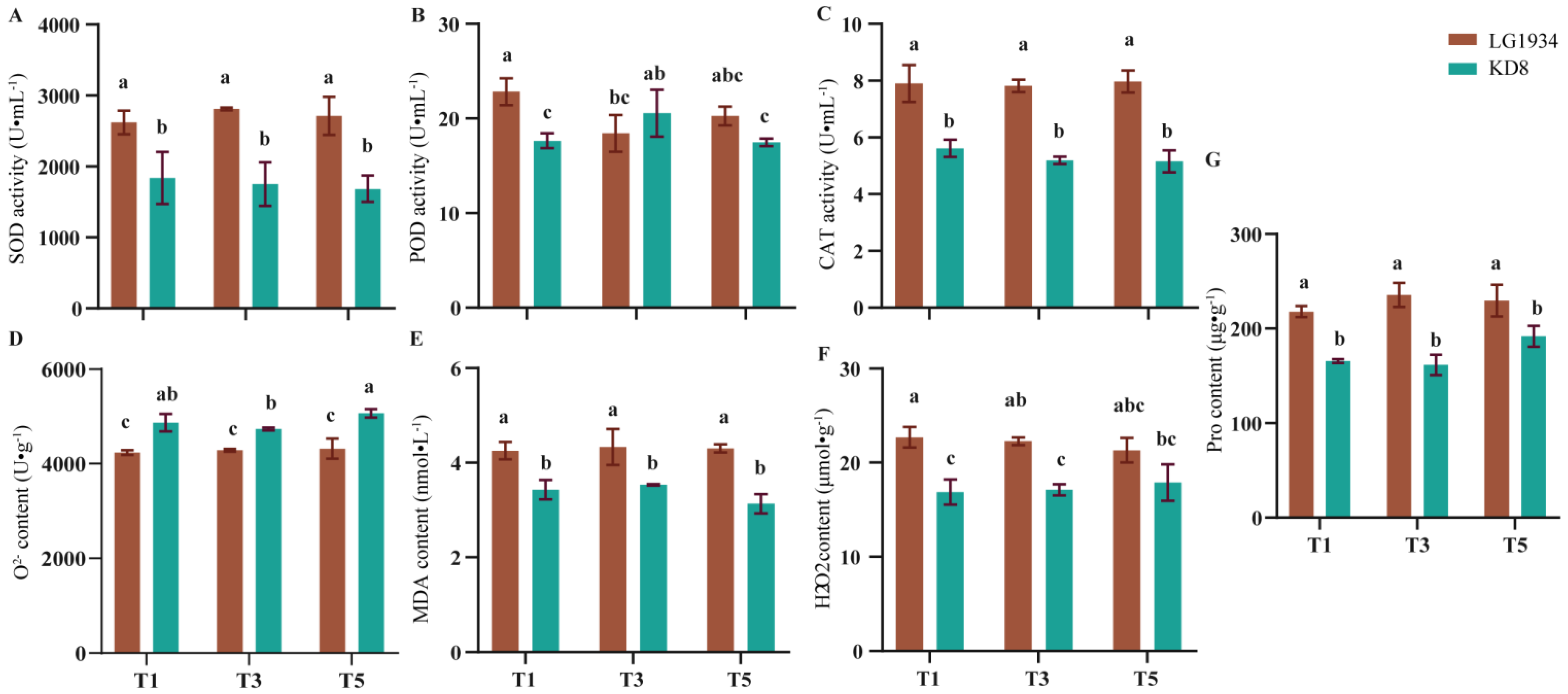

3.2. Effects of Low-Temperature Treatment on the Antioxidant System

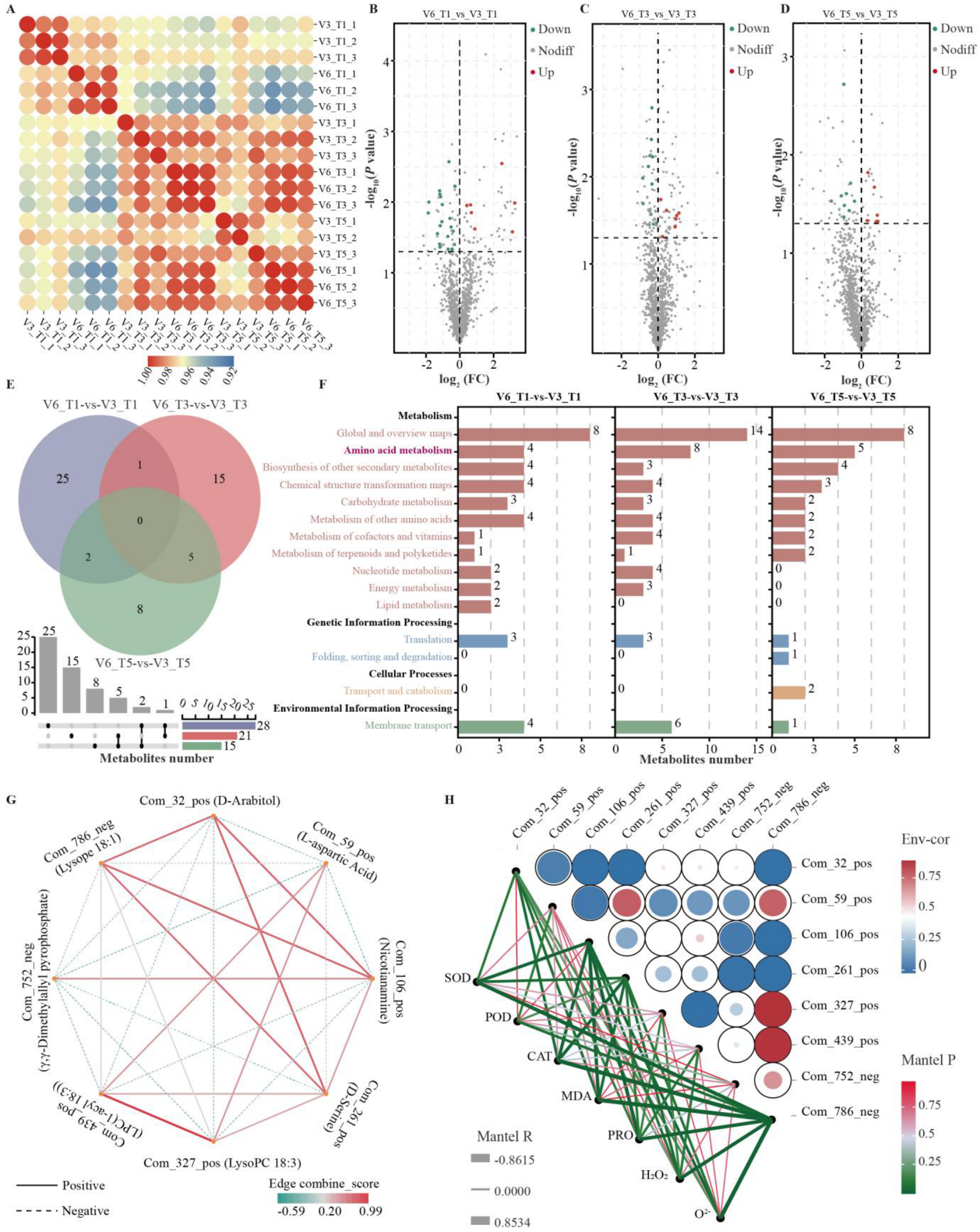

3.3. Identification of Metabolites in Cold-Tolerant and Cold-Sensitive Rice Under Low-Temperature Stress

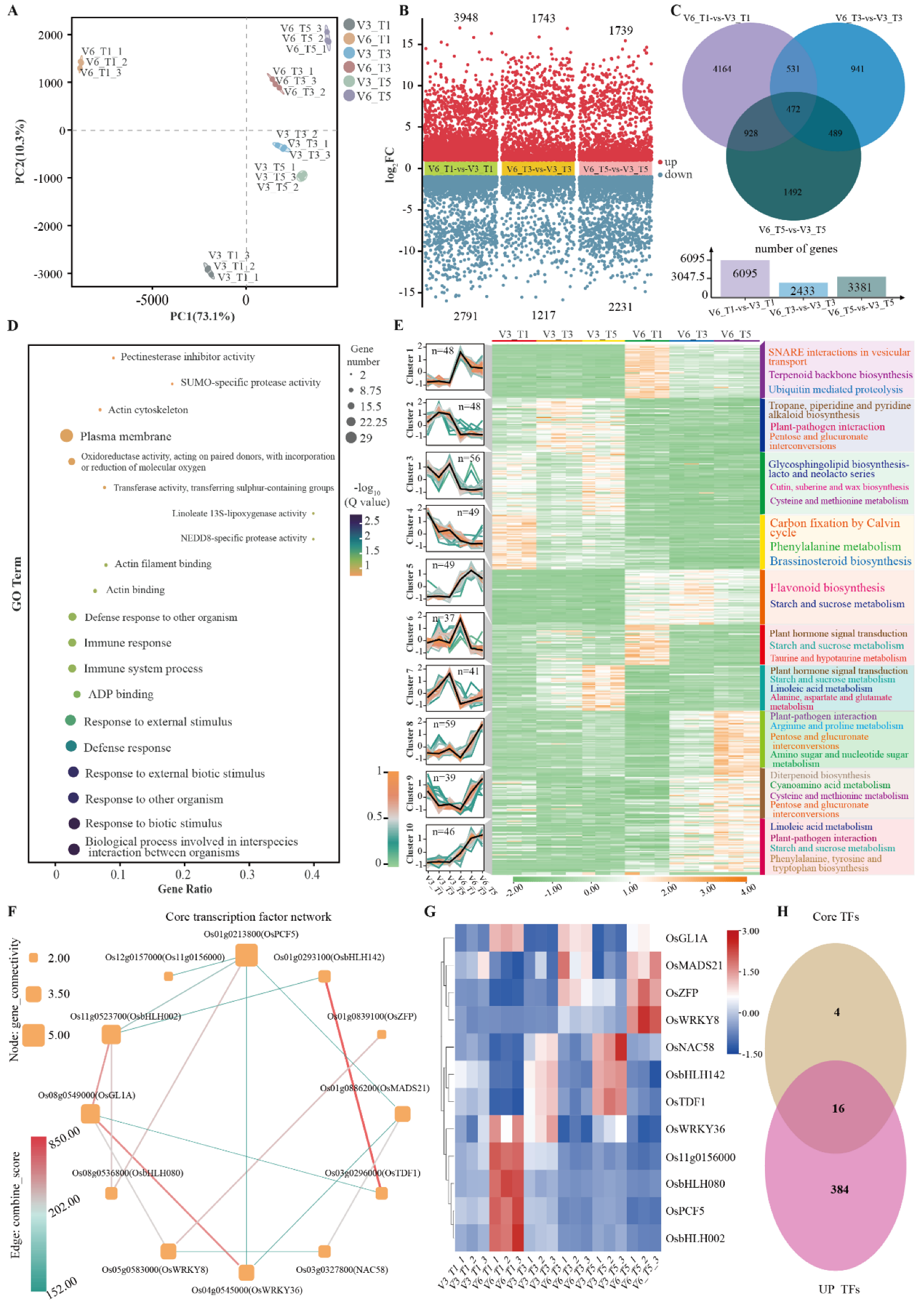

3.4. Effects of Low-Temperature Stress on the Transcriptome of Cold-Tolerant and Cold-Sensitive Rice

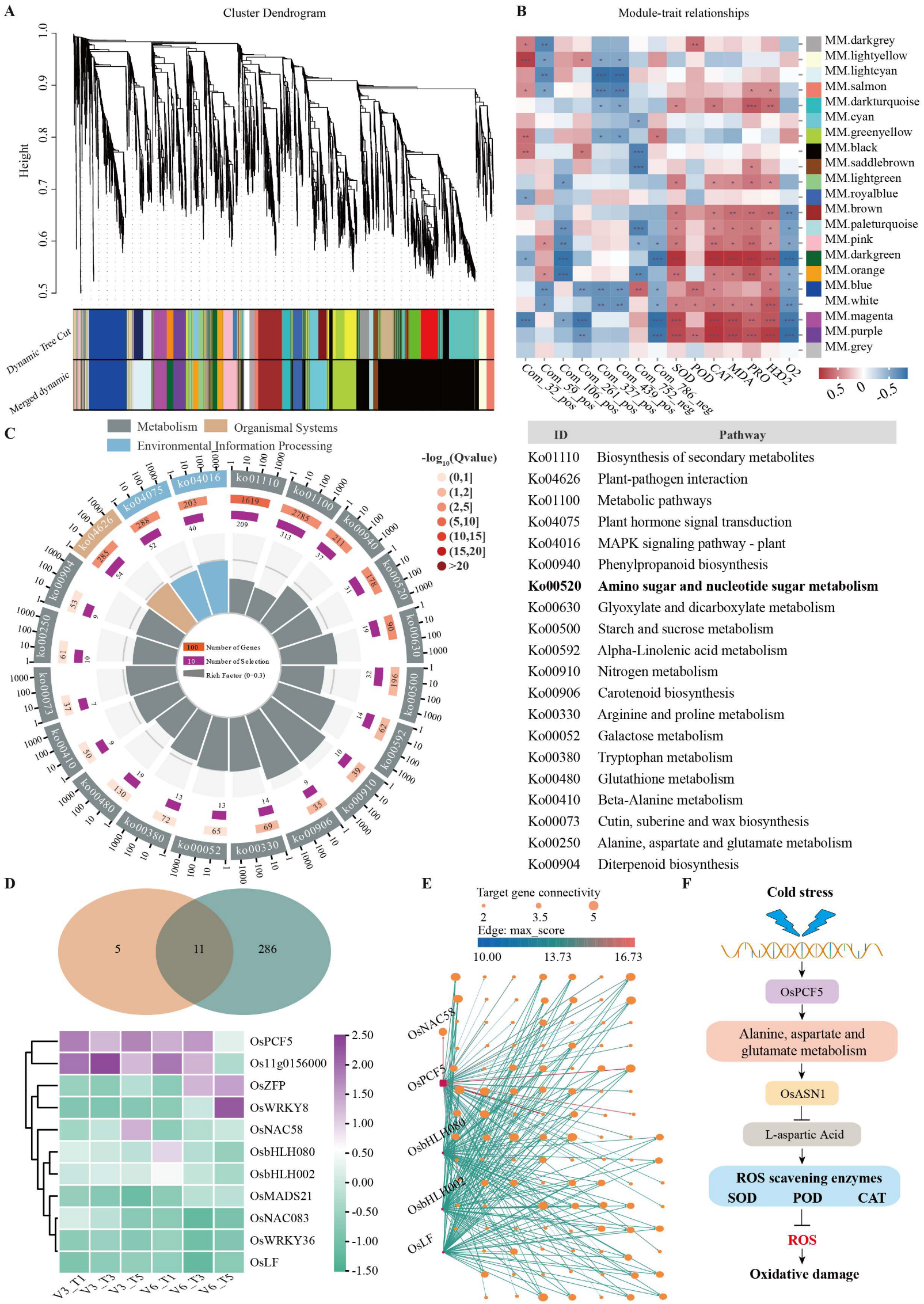

3.5. Integrated Analysis of Differential Metabolites and Genes in Response to Cold Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Low Temperature at Booting Stage on Rice Agronomic Traits

4.2. Impact of Cold Stress on Rice Antioxidant System

4.3. Regulatory Role of Aspartate and Its Metabolic Pathway in Rice Cold Tolerance

4.4. Co-Expression Network Analysis Revealed Core Cold-Tolerance Candidate Genes and Regulatory Pathways

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wing, R.A.; Purugganan, M.D.; Zhang, Q. The rice genome revolution: From an ancient grain to Green Super Rice. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Kang, H.; Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Liu, M.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Genome-wide association mapping of cold tolerance genes at the seedling stage in rice. Rice 2016, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhu, X.; Cao, T.; Li, S.; Guo, E.; Shi, Y.; Guan, K.; Li, E.; Sun, R.; Wang, X.; et al. Responses of rice cultivars with different cold tolerance to chilling in booting and flowering stages: An experiment in Northeast China. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2023, 209, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, N.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Fu, G.; Liu, F.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Xia, T.; et al. Integrated transcriptome and co-expression network analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of cold tolerance in japonica rice at booting stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1629202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, H.; Lou, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xu, P.; Gu, Y.; Gao, S.; Xu, B.; Han, S.; et al. Natural variation of indels in the CTB3 promoter confers cold tolerance in japonica rice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaya, V.C.; Mackill, D.J. Mapping of QTLs associated with cold tolerance during the vegetative stage in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 2579–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, R.; Huang, K.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.; Li, Z.; Bian, M.; Jiang, W.; Wu, T.; et al. The OsWRKY63–OsWRKY76–OsDREB1B module regulates chilling tolerance in rice. Plant J. 2022, 112, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örvar, B.L.; Sangwan, V.; Omann, F.; Dhindsa, R.S. Early steps in cold sensing by plant cells: The role of actin cytoskeleton and membrane fluidity. Plant J. 2000, 23, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, S. Advances and challenges in uncovering cold tolerance regulatory mechanisms in plants. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1690–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Surviving and thriving: How plants perceive and respond to temperature stress. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, B.; et al. Rice transcriptional repressor OsTIE1 controls anther dehiscence and male sterility by regulating JA biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1697–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Barbosa, A.D.; Hutin, S.; Kumita, J.R.; Gao, M.; Derwort, D.; Silva, C.S.; Lai, X.; Pierre, E.; Geng, F.; et al. A prion-like domain in ELF3 functions as a thermosensor in Arabidopsis. Nature 2020, 585, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.M.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, Y.W.; Wang, F.M.; Zhang, H.L.; Shen, S.Q.; Li, Z.C. Identification and mapping of quantitative trait loci for cold tolerance at the booting stage in a japonica rice near-isogenic line. Plant Sci. 2008, 174, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Hayano-Saito, Y.; Maruyama-Funatsuki, W.; Sato, Y.; Kato, A. Physical mapping and putative candidate gene identification of a quantitative trait locus Ctb1 for cold tolerance at the booting stage of rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Miura, K.; Nagano, K.; Hayano-Saito, Y.; Araki, H.; Kato, A. Identification of two closely linked quantitative trait loci for cold tolerance on chromosome 4 of rice and their association with anther length. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, S.; Zheng, W.; et al. Natural variation in CTB4a enhances rice adaptation to cold habitats. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Masuta, Y.; Saito, K.; Murayama, S.; Ozawa, K. Enhanced chilling tolerance at the booting stage in rice by transgenic overexpression of the ascorbate peroxidase gene, OsAPXa. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.H.; Yu, D.J.; Im, D.; Kim, S.J.; Hur, Y.Y.; Chung, S.W.; Lee, H.J. Searching for cold hardiness related genes based on transcriptome profiling in grapevine canes during cold acclimation and deacclimation. J. Horticul. Sci. Biotech. 2025, 100, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, M.; Miao, X.; Shi, Z. OsmiR319-OsPCF5 modulate resistance to brown planthopper in rice through association with MYB proteins. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, D.; Mao, D.; Liu, X.; Ji, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhu, L. Overexpression of microRNA319 impacts leaf morphogenesis and leads to enhanced cold tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, P.; Browse, J. Male sterility in Arabidopsis induced by overexpression of a MYC5-SRDX chimeric repressor. Plant J. 2015, 81, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, T.; Huang, H.; Song, S.; Xie, D. Regulation of jasmonate-mediated stamen development and seed production by a bHLH-MYB complex in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1620–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Yang, J.; Jia, B.; Dong, W.; Chen, X.; Sun, X. Osa-miR1320 targets the ERF transcription factor OsERF096 to regulate cold tolerance via JA-mediated signaling. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 2500–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, C.; Halitschke, R.; Paetz, C.; Kessler, D.; Burkard, K.; Gaquerel, E.; Baldwin, I.T.; Li, D. Natural history–guided omics reveals plant defensive chemistry against leafhopper pests. Science 2022, 375, eabm2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, S.; Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Y.; An, L.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, W.; et al. Rice metabolic regulatory network spanning the entire life cycle. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Sun, R.; Lou, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, R. The MYC2-JAMYB transcriptional cascade regulates rice resistance to brown planthoppers. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 1834–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, L.; Zhao, N.; Liao, K.; Sun, X.; Wang, Q.; Jin, H. Metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the toxic mechanism of Cd and nano TiO2 coexposure on rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 453, 131411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, S.; Masangano, M.; Kang, M.; Cao, X.; Huang, P.; Gao, Y.; Pei, X.; et al. Gene expression modules during the emergence stage of upland cotton under low-temperature stress and identification of the GhSPX9 cold-tolerance gene. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 218, 109320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, X.; Song, Q.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lai, Y. Identification of key genes and modules in response to Cadmium stress in different rice varieties and stem nodes by weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Yang, G.; He, C. Progress in transcriptomics and metabolomics in plant responses to abiotic stresses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Meng, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, B.; Hou, X.L.; Yan, B.; Yang, C.; Guo, Z.; et al. Inheritance of acquired adaptive cold tolerance in rice through DNA methylation. Cell 2025, 188, 4213–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ashraf, U.; Tian, H.; Mo, Z.; Pan, S.; Anjum, S.A.; Duan, M.; Tang, X. Manganese-induced regulations in growth, yield formation, quality characters, rice aroma and enzyme involved in 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline biosynthesis in fragrant rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 103, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Fang, Z.; Wang, C.; Cheng, X.; Huang, F.; Yan, C.; Zhou, L.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y. Modulation of 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline (2-AP) accumulation, yield formation and antioxidant attributes in fragrant rice by exogenous methylglyoxal (MG) application. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 1444–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Kong, L.; Ma, L.; Ashraf, U.; Pan, S.; Duan, M.; Tian, H.; Wu, L.; Tang, X.; Mo, Z. Enhancement of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) concentration, total yield, and quality in fragrant rice through exogenous γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) application. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 91, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, X. Application of glutamic acid improved As tolerance in aromatic rice at early growth stage. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.; Ashraf, U.; Huang, S.; Cheng, S.; Abrar, M.; Mo, Z.; Pan, S.; Tang, X. Ultrasonic seed treatment improved physiological and yield traits of rice under lead toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 33637–33644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Rao, G.; Ashraf, U.; Deng, Q.; Dong, H.; Zhang, H.; Mo, Z.; Pan, S.; Tang, X. Ultrasonic seed treatment improved morpho-physiological and yield traits and reduced grain Cd concentrations in rice. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2021, 214, 112119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cai, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Pan, G.; Ma, W. Comparative metabolome profiling for revealing the effects of different cooking methods on glutinous rice Longjing57 (Oryza sativa L. var. Glutinosa). Foods 2024, 13, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Liu, Y.; Djoumbou, Y.; Mandal, R.; Aziat, F.; Dong, E.; et al. HMDB 3.0—The Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-J.; Schultz, A.W.; Wang, J.; Johnson, C.H.; Yannone, S.M.; Patti, G.J.; Siuzdak, G. Liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry characterization of metabolites guided by the METLIN database. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, L.; He, W.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; et al. A complete assembly of the rice Nipponbare reference genome. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Huang, G.; Deng, M.; Hong, S.; Ai, P.; Gao, C.; Zhou, H. OmicShare tools: A zero-code interactive online platform for biological data analysis and visualization. iMeta 2024, 3, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Wang, J.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Fan, Y.; Cui, L.; Li, C.; Guo, C. Cold stress response mechanisms in anther development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.; Islam, S.; Mohammad, F.; Siddiqui, M.H. Gibberellic acid: A versatile regulator of plant growth, development and stress responses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 7352–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Fu, S.; Yang, Y. Signaling and scavenging: Unraveling the complex network of antioxidant enzyme regulation in plant cold adaptation. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhou, H.; Tan, L.; Li, Q.; Hou, Y.; Li, W.; Kafle, S.; Liang, J.; Aryal, R.; Liang, Z.; et al. VaWRKY65 contributes to cold tolerance through dual regulation of soluble sugar accumulation and reactive oxygen species scavenging in Vitis amurensis. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Hwarari, D.; Korboe, H.M.; Ahmad, B.; Cao, Y.; Movahedi, A.; Yang, L. Low temperature stress-induced perception and molecular signaling pathways in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 207, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Song, R.F.; Qiu, Y.M.; Zheng, S.Q.; Li, T.T.; Wu, Y.; Song, C.P.; Lu, Y.T.; Yuan, H.M. Sulfenylation of ENOLASE2 facilitates H2O2-conferred freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Kato, H.; Sasaki, K.; Imai, R. A cold-induced thioredoxin h of rice, OsTrx23, negatively regulates kinase activities of OsMPK3 and OsMPK6 in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 2734–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Sun, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Si, Y.; Hu, Y.; Su, T. Investigation of stimulated growth effect by application of L-aspartic acid on poplar. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 209, 118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, G.; Rohloff, J.; Wilson, R.C.; Kopka, J.; Erban, A.; Winge, P.; Bones, A.M.; Davik, J.; Alsheikh, M.K.; Randall, S.K. Integrative “omic” analysis reveals distinctive cold responses in leaves and roots of strawberry, Fragaria × ananassa ‘Korona’. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byeon, S.E.; Lee, J. Differential responses of fruit quality and major targeted metabolites in three different cultivars of cold-stored figs (Ficus carica L.). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Rossi, S.; Huang, B. Metabolic and physiological regulation of aspartic acid-mediated enhancement of heat stress tolerance in Perennial Ryegrass. Plants 2022, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhang, C.; Suglo, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, M.; Su, T. l-Aspartate: An essential metabolite for plant growth and stress acclimation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Qin, R.; Liu, T.; Yu, M.; Yang, T.; Xu, G. OsASN1 plays a critical role in asparagine-dependent rice development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Fu, D.; Wu, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Lai, J.; et al. Natural polymorphism of ZmICE1 contributes to amino acid metabolism that impacts cold tolerance in maize. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chong, K. OsMADS57 together with OsTB1 coordinates transcription of its target OsWRKY94 and D14 to switch its organogenesis to defense for cold adaptation in rice. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.R.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, K.S.; Hwang, D.J.; Bae, S.C.; Ahn, I.P.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.T. Overexpression of rice NAC transcription factor OsNAC58 on increased resistance to bacterial leaf blight. J. Plant Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Q.J. The WRKY gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, W.; Guo, Z.; Li, P.; Cao, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanisms of Cold Stress in Japonica Rice at the Booting Stage. Agriculture 2026, 16, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010019

Ma W, Guo Z, Li P, Cao H, Cai Y, Zhang X, Han X, Feng Y, Li J, Li Z. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanisms of Cold Stress in Japonica Rice at the Booting Stage. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Wendong, Zhenhua Guo, Peng Li, Hu Cao, Yongsheng Cai, Xirui Zhang, Xiao Han, Yanjiang Feng, Jinjie Li, and Zichao Li. 2026. "Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanisms of Cold Stress in Japonica Rice at the Booting Stage" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010019

APA StyleMa, W., Guo, Z., Li, P., Cao, H., Cai, Y., Zhang, X., Han, X., Feng, Y., Li, J., & Li, Z. (2026). Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanisms of Cold Stress in Japonica Rice at the Booting Stage. Agriculture, 16(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010019