Load Dynamic Characteristics and Energy Consumption Model of Manipulator Joints for Picking Robots Based on Bond Graphs: Taking Joints V and VI as Examples

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A bond graph model of the citrus-picking manipulator joint system is established. Based on bond graph theory, the state-space equations describing the joint dynamics and an energy consumption model are derived for joints V and VI, clarifying component interactions and energy conversion relationships.

- The dynamic responses and energy consumption characteristics of the joint system are investigated under different operating conditions. Using the derived models and simulation results, the joint dynamic behaviour and energy consumption patterns are quantified and interpreted.

- Experimental validation is conducted to verify the proposed model. Results obtained from a dedicated test platform demonstrate that the model can accurately capture joint dynamics as well as energy transfer and dissipation, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing joint parameters and load allocation of the harvesting manipulator.

2. Materials and Methods

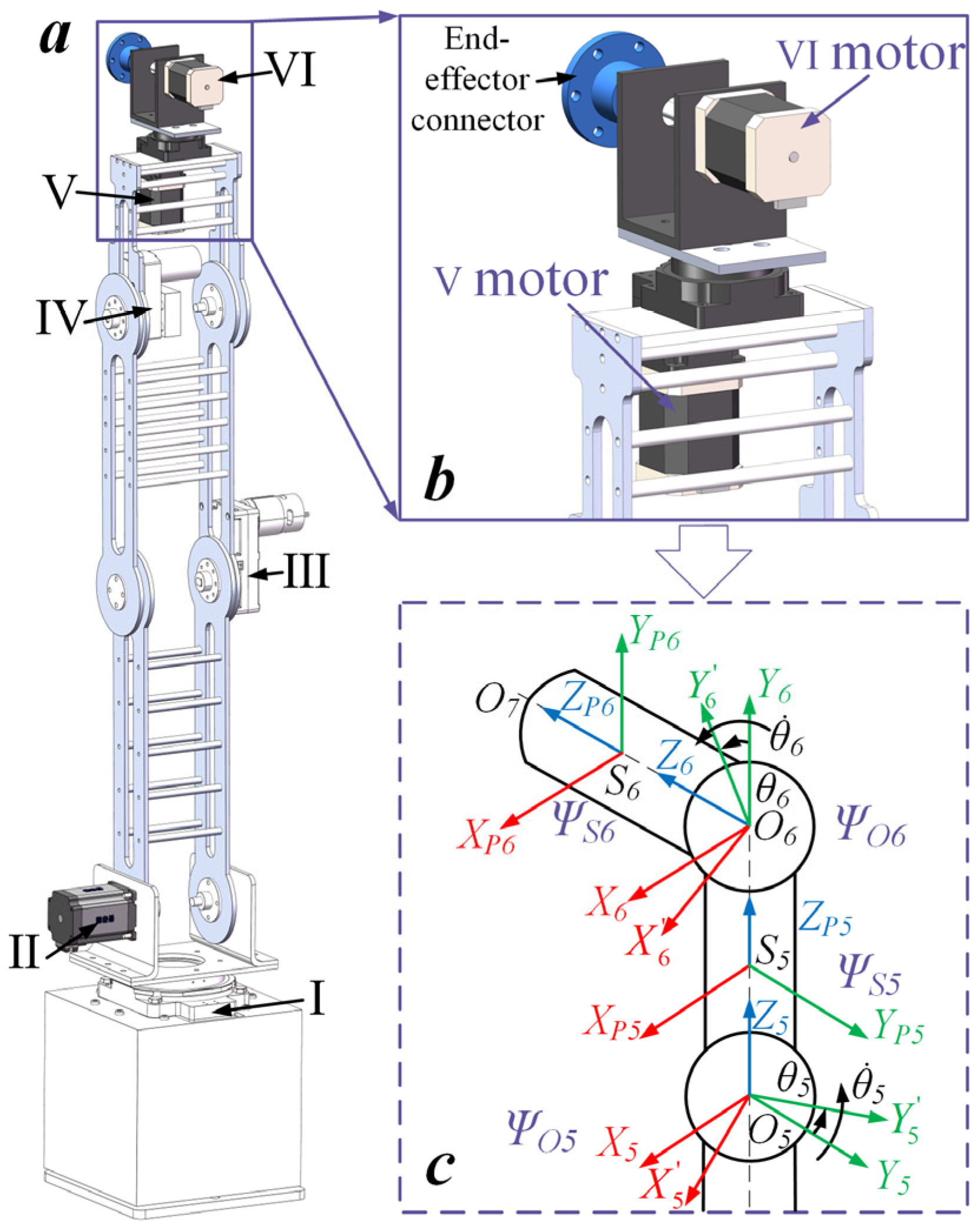

2.1. Physical Model

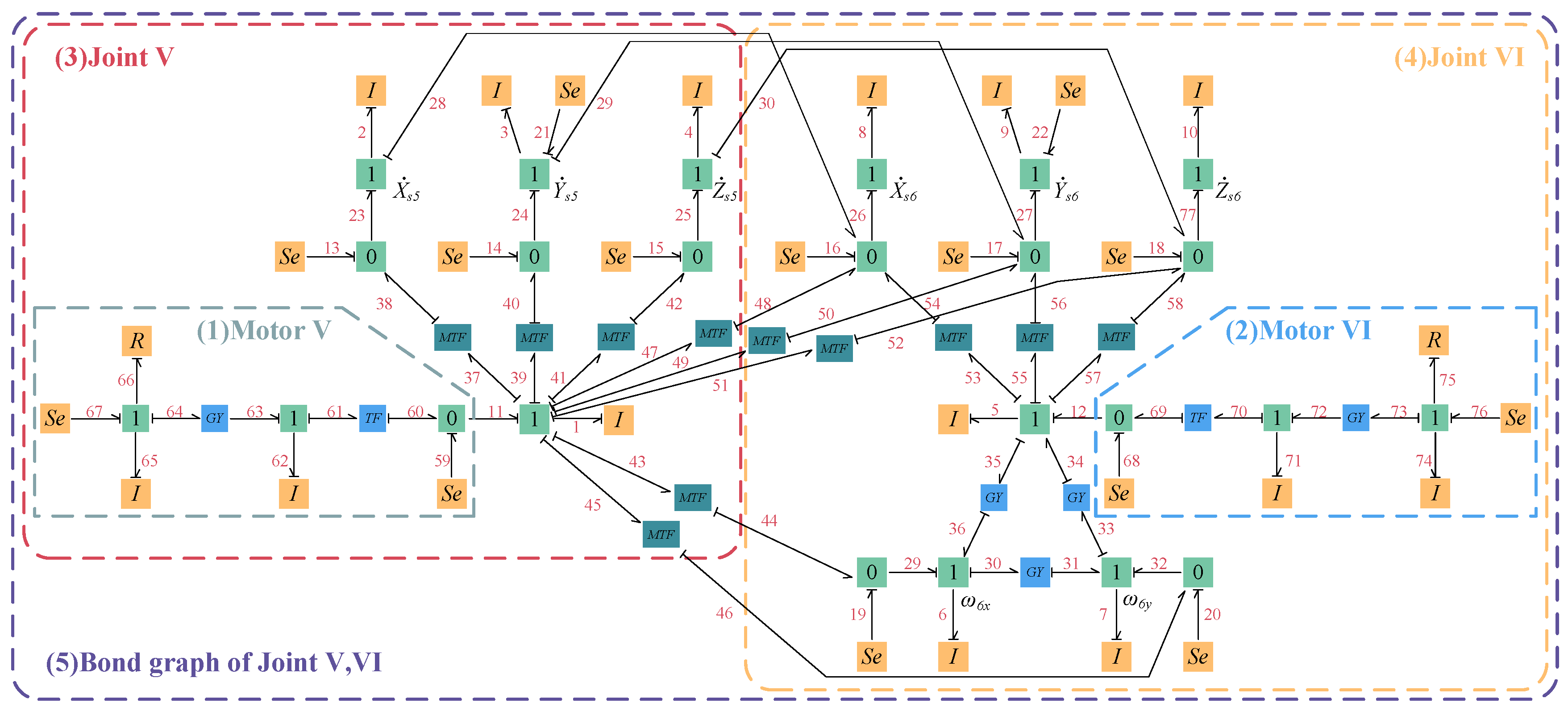

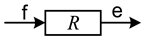

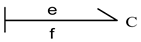

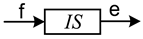

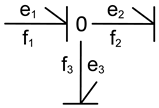

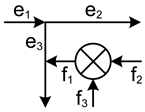

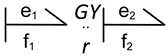

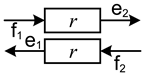

2.2. Bond Graph Model

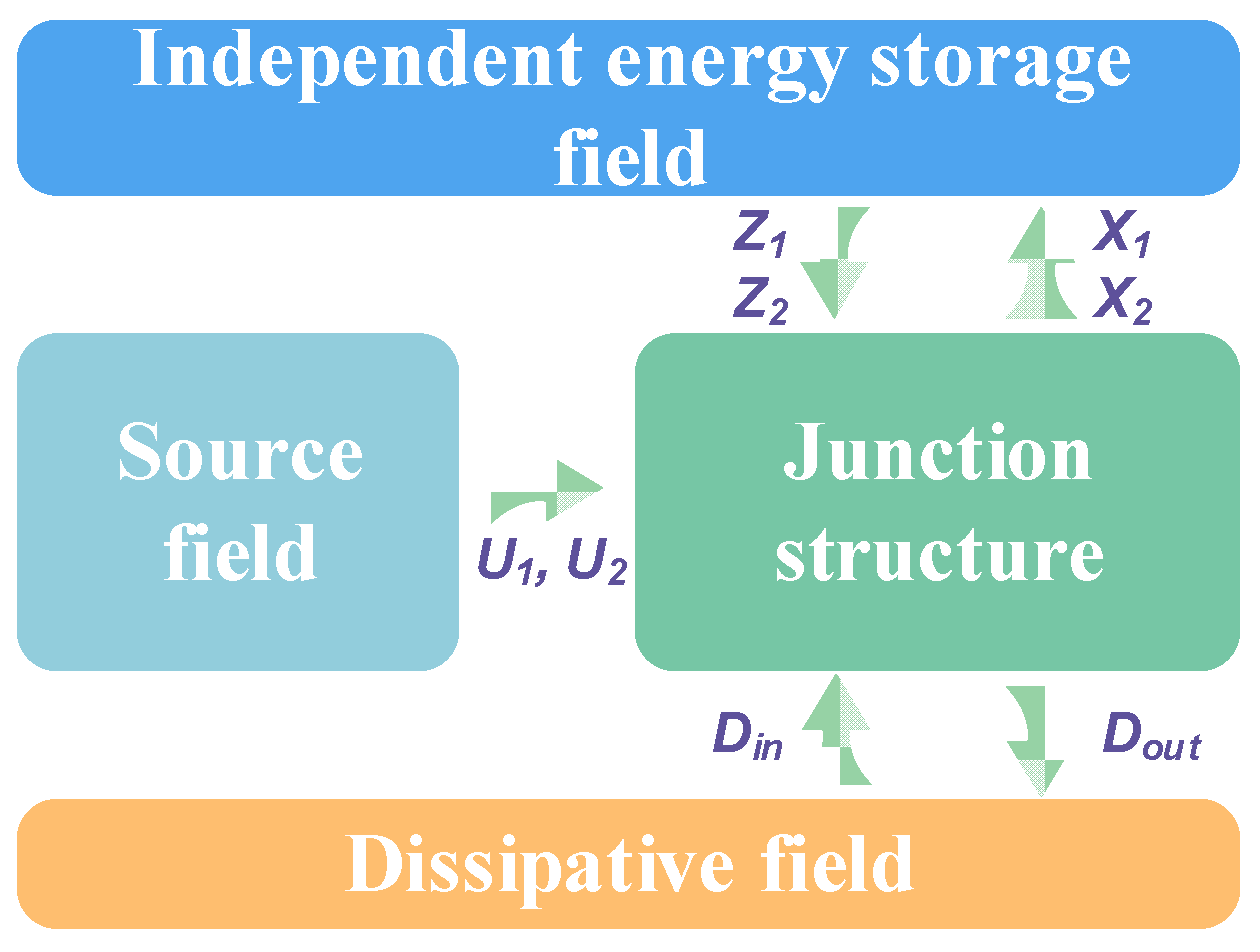

2.2.1. System Energy Field

2.2.2. Bond Graph Model of the Manipulator Joint System

2.3. Equation of State

2.3.1. Manipulator Joint Speed

2.3.2. Junction Structural Equation

2.3.3. Dynamic Characteristics State Equation of the Manipulator

2.4. Energy Consumption Model

3. Results and Discussion

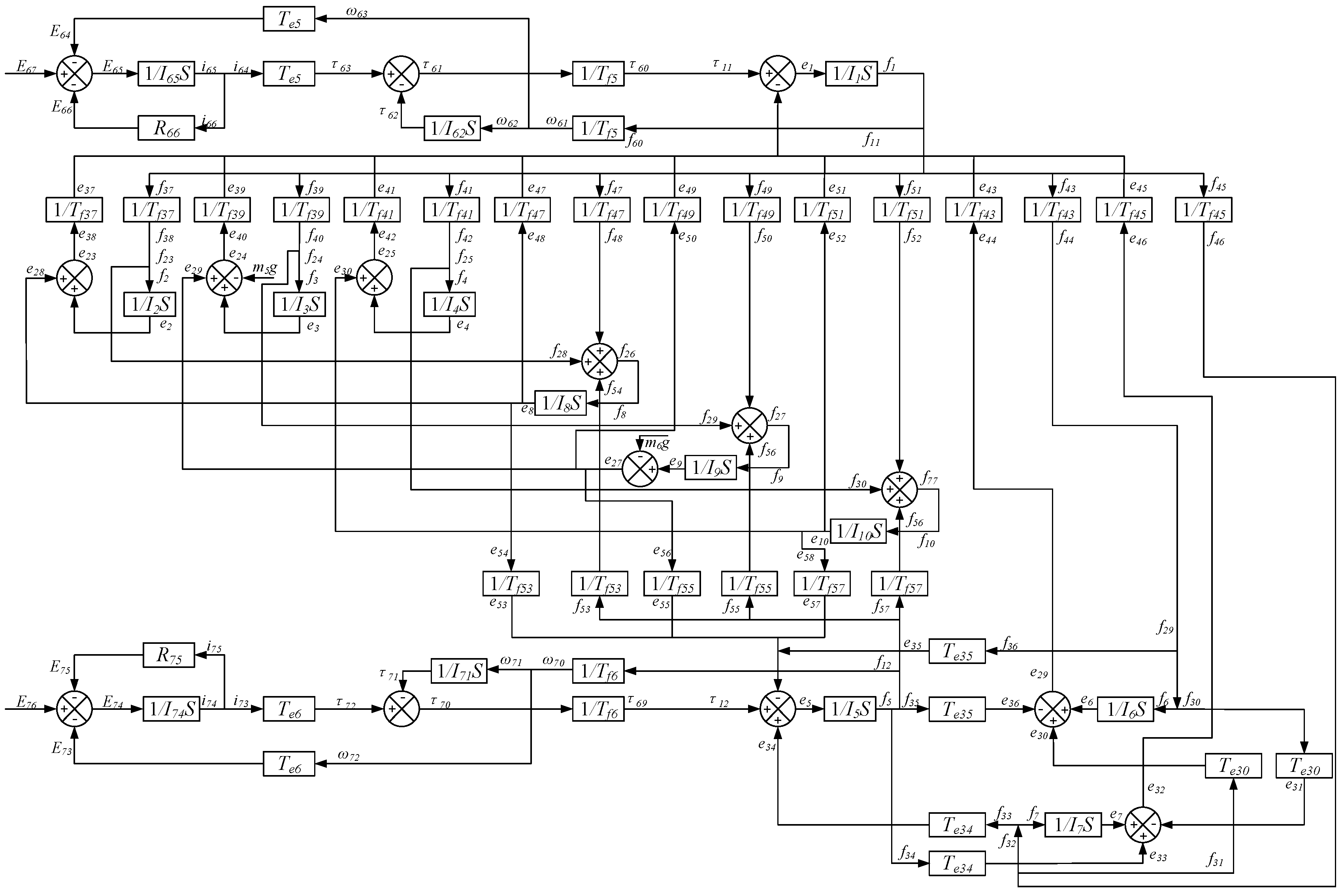

3.1. Block Diagram Model of the Manipulator Joint System

3.2. Manipulator Condition Parameters

3.3. Matlab-Simulink Solution Analysis

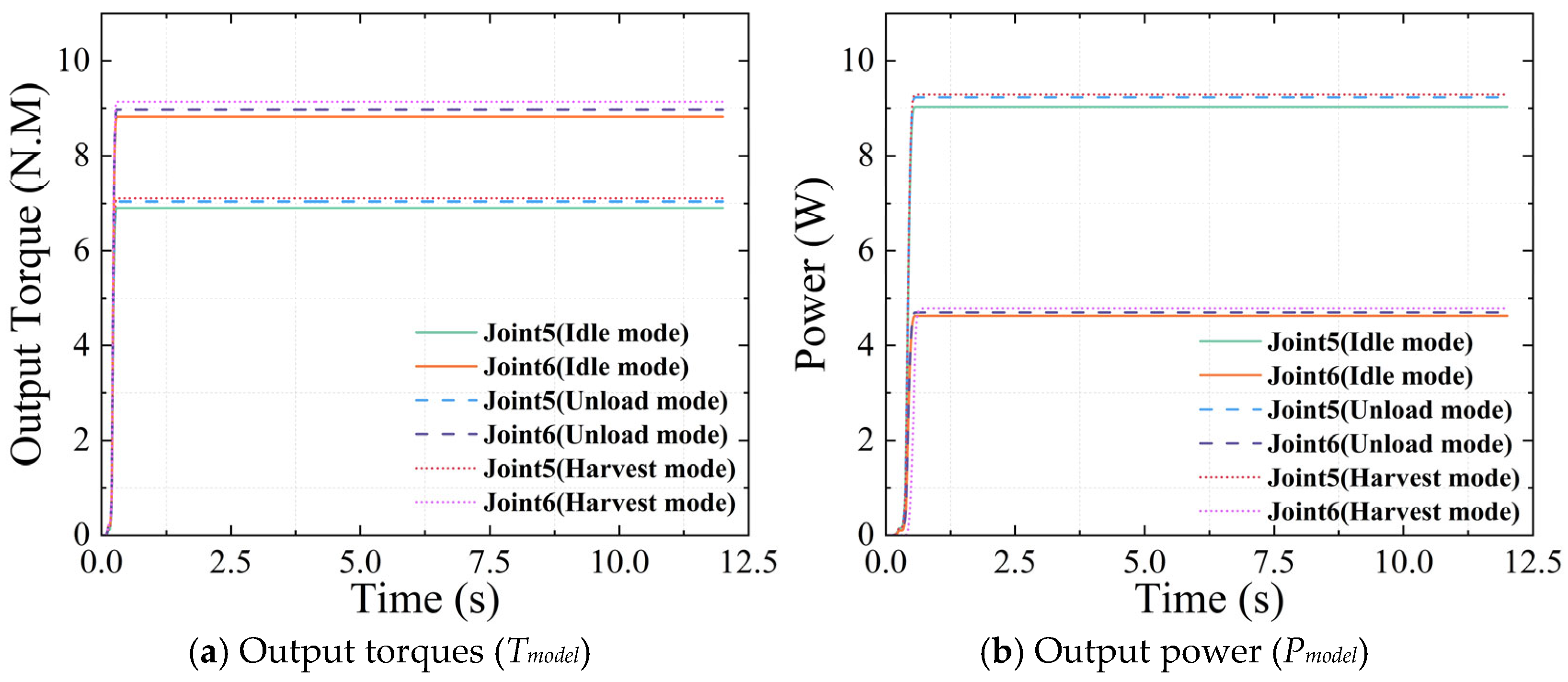

3.4. Results

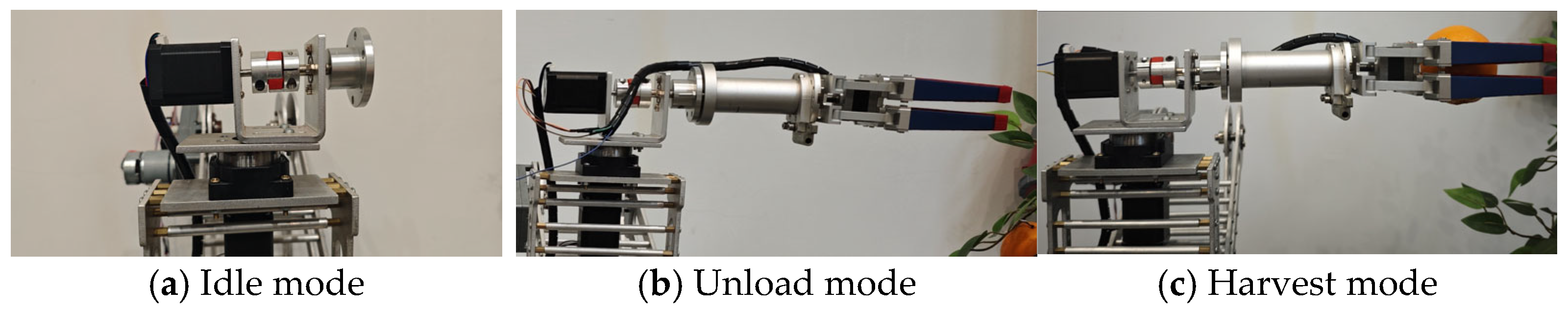

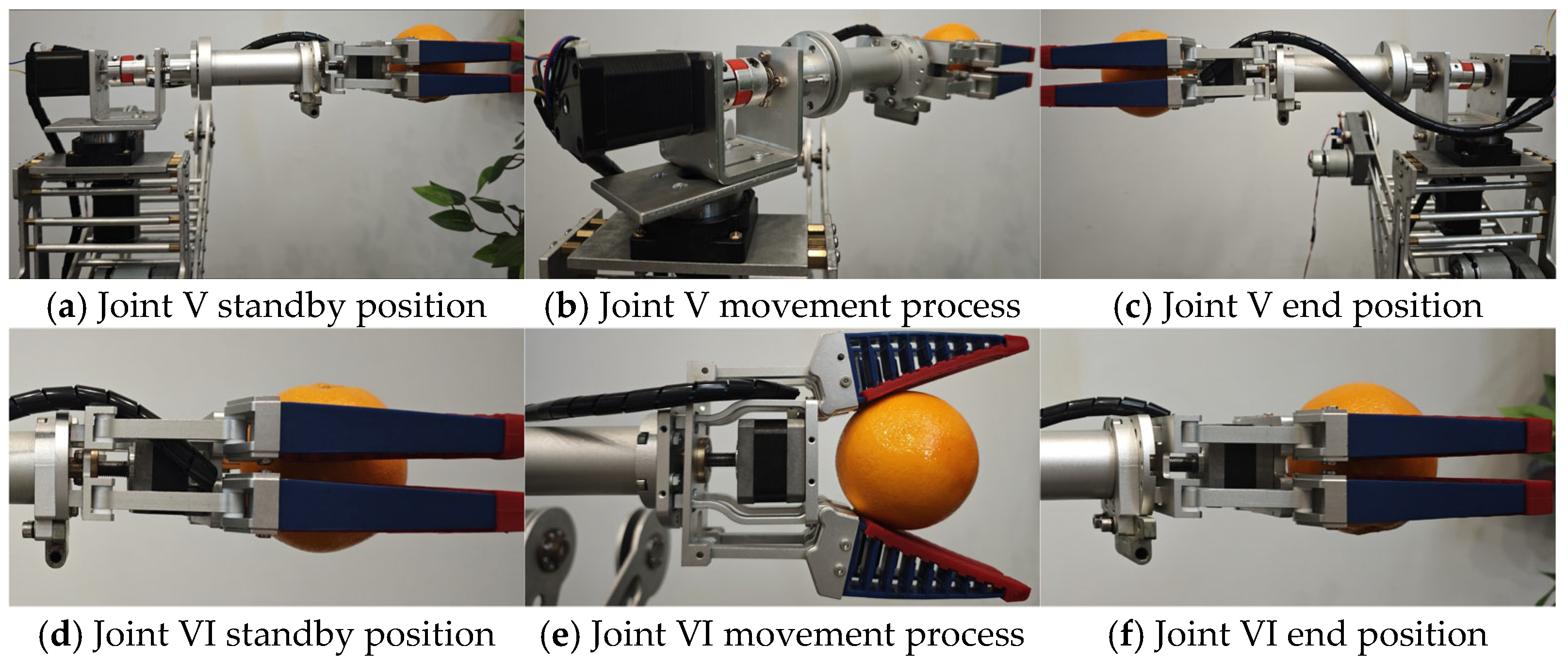

3.4.1. Experimental Setup

3.4.2. Experimental Procedures

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. State Equation Specific Matrix

References

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chun, C.; Wen, Y.; Xu, G. Multi-scale feature adaptive fusion model for real-time detection in complex citrus orchard environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Citrus Organisation. The World Citrus Organisation Northern Hemisphere Citrus Forecast Shows Recovery in Citrus Production; World Citrus Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chun, C.; Wen, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, G. Data-driven Bayesian Gaussian mixture optimized anchor box model for accurate and efficient detection of green citrus. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Chun, C. Citrus pose estimation under complex orchard environment for robotic harvesting. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 162, 127418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Shi, X.; Ma, X.; Leng, J.; Ma, Z.; Ren, M.; Li, S. Design and experiment of citrus picking system based on dual robot collaboration. J. Eng. 2024, 2024, e12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.D. Harvesting citrus: Challenges and perspectives in an automated world. In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Tropical Fruits; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Au, C.; Barnett, J.; Lim, S.; Duke, M. Workspace analysis of Cartesian robot system for kiwifruit harvesting. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2020, 47, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytridis, C.; Bazinas, C.; Kalathas, I.; Siavalas, G.; Tsakmakis, C.; Spirantis, T.; Badeka, E.; Pachidis, T.; Kaburlasos, V. Cooperative Grape Harvesting Using Heterogeneous Autonomous Robots. Robotics 2023, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Q.; He, W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Addy, M. Design and Experiment of Nighttime Greenhouse Tomato Harvesting Robot. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2024, 56, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Sun, Q.; Ren, X.; Guo, J.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Huang, B.; Chai, X.; Zhong, M. Development, integration, and field evaluation of an autonomous citrus-harvesting robot. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1363–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Park, J.; Yoo, J.; Ko, K. AI-driven adaptive grasping and precise detaching robot for efficient citrus harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, P.; Li, J.; Ekaterina, S.; Wang, B. Stability analysis of human hand grasping for the design of pneumatic muscle-driven end effector targeting citrus picking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Gu, W.; Feng, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Dynamic analysis and driving force optimization of a 5-DOF parallel manipulator with redundant actuation. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2017, 48, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, F. Dynamic response investigation of high-speed structural redundant parallel manipulator considering multiple spatial revolute joints with radial and axial clearances. Mech. Based Des. Struc. Mach. 2024, 52, 6633–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayro-Corrochano, E.; Medrano-Hermosillo, J.; Osuna-González, G.; Uriostegui-Legorreta, U. Newton–Euler modeling and Hamiltonians for robot control in the geometric algebra. Robotica 2022, 40, 4031–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodargi, N.; Bisegna, P. A variational-based non-smooth contact dynamics approach for the seismic analysis of historical masonry structures. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 432, 117346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Chen, J.; Tian, Q. An implicit asynchronous variational integrator for flexible multibody dynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 401, 115660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidussi, F.; Boscariol, P.; Scalera, L.; Gasparetto, A. Local and Trajectory-Based Indexes for Task-Related Energetic Performance Optimization of Robotic Manipulators. J. Mech. Robot. 2021, 13, 021018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Cui, T.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H. Design and simulation experiment of ridge planting strawberry picking manipulator. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Q.; Fu, W.; Gu, Y.; Liu, J. Analysis and Experimentation on the Motion Characteristics of a Dragon Fruit Picking Robot Manipulator. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jeon, H.; Park, K. Power estimation models of a 7-axis manipulator with simulated manufacturing applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 4161–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yao, S.; Zhu, S. Energy-saving trajectory optimization of a fluidic soft manipulator. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 115011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzarovsky, R.; Horak, T.; Bocak, R. Evaluating Energy Efficiency and Optimal Positioning of Industrial Robots in Sustainable Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X.; Yuan, H. Energy consumption modeling based on operation mechanisms of industrial robots. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2025, 94, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ji, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Tan, J. An energy-saving optimization method for cyclic pick-and-place tasks based on flexible joint configurations. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhedi, F.; Khlif, R.; Nouri, A.; Derbel, N. Fuzzy fractional order sliding mode control for optimal energy consumption-transient response trade-off in robotic systems. Fractals 2024, 32, 2450094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabar, I.; Vasiljevic, G.; Kovacic, Z. Estimation of the Energy Consumption of an All-Terrain Mobile Manipulator for Operations in Steep Vineyards. Electronics 2022, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Taylor, N.; Stokes, A. Energy-Based Abstraction for Soft Robotic System Development. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 5, 2000264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusila, V.; Emami, M. Modelling of a robotic leg using bond graphs. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2014, 40, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Amirouche, F. Kane’s equations for nonholonomic systems in bond-graph-compatible velocity and momentum forms. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2023, 59, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Cai, W.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Sutherland, J. Dynamic characteristics and energy consumption modelling of machine tools based on bond graph theory. Energy 2020, 212, 118767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Cai, W.; Sutherland, J. Dynamics analysis and energy consumption modelling based on bond graph: Taking the spindle system as an example. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cui, Y. Dynamic characteristics of single-loop gear system based on bond graph method. J. Vibroeng. 2022, 24, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Guillén, J.; Salas-Cabrera, R.; García-Vite, P. Bond Graph as a formal methodology for obtaining a wind turbine drive train model in the per-unit system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 124, 106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grava, A.; Marian, M.; Grava, C.; Curila, S.; Trip, N. Bond-graph analysis and modelling of a metal detector as an example of electro-magnetic system. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yan, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, W. Bond Graph-Based Approach to Modeling Variable-Speed Gearboxes with Multi-Type Clutches. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Block Diagram Unit | Element | Block Diagram Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

| Rod (i) | Mass (kg) | Length (mm) | Iixx (kg·m2) | Iiyy (kg·m2) | Iizz (kg·m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.73 | 60 | - | - | 6.0 × 10−3 |

| 6 | 0.1 | 120 | 0.1252 | 0.1194 | 6.6 × 10−3 |

| Parameters | Numerical Value |

|---|---|

| Le/H | 5.4 × 10−3 |

| Re/Ω | 2.3 |

| Je/kg.m2 | 7.2 × 10−7 |

| Te/[(N·m)A−1] | 0.39 |

| Condition | Baud rate | Ambient temperature(°C) | Acquisition frequency(s) |

| 9600 | 35 | 0.1 |

| V Joint | VI Joint | |

|---|---|---|

| ne | 12.5 r/min | 5 r/min |

| Tea (Idle mode) | 6.977 N·m | 8.859 N·m |

| Pea (Idle mode) | 9.1332 W | 4.6386 W |

| Tea (Unload mode) | 7.112 N·m | 9.04 N·m |

| Pea (Unload mode) | 9.3096 W | 4.7331 W |

| Tea (Harvest mode) | 7.24 N·m | 9.337 N·m |

| Pea (Harvest mode) | 9.481 W | 4.8893 W |

| Joint | Mode | Tmodel (N·m) | Tmeasured (N·m) | Relative Error (%) | Pmodel (W) | Pmeasured (W) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Idle mode | 6.903 | 6.977 | 1.061 | 9.03 | 9.133 | 1.126 |

| Unload mode | 7.032 | 7.112 | 1.122 | 9.223 | 9.31 | 1.258 | |

| Harvest mode | 7.103 | 7.24 | 1.888 | 9.291 | 9.481 | 2.002 | |

| 6 | Idle mode | 8.83 | 8.859 | 0.33 | 4.623 | 4.639 | 0.331 |

| Unload mode | 8.957 | 9.04 | 0.883 | 4.675 | 4.733 | 0.861 | |

| Harvest mode | 9.14 | 9.337 | 2.109 | 4.781 | 4.889 | 2.218 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chun, C.; Li, C.; Xu, G.; Li, L. Load Dynamic Characteristics and Energy Consumption Model of Manipulator Joints for Picking Robots Based on Bond Graphs: Taking Joints V and VI as Examples. Agriculture 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010014

Xie J, Zhang Y, Chun C, Li C, Xu G, Li L. Load Dynamic Characteristics and Energy Consumption Model of Manipulator Joints for Picking Robots Based on Bond Graphs: Taking Joints V and VI as Examples. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Jinzhi, Yunfeng Zhang, Changpin Chun, Congbo Li, Gang Xu, and Li Li. 2026. "Load Dynamic Characteristics and Energy Consumption Model of Manipulator Joints for Picking Robots Based on Bond Graphs: Taking Joints V and VI as Examples" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010014

APA StyleXie, J., Zhang, Y., Chun, C., Li, C., Xu, G., & Li, L. (2026). Load Dynamic Characteristics and Energy Consumption Model of Manipulator Joints for Picking Robots Based on Bond Graphs: Taking Joints V and VI as Examples. Agriculture, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010014