The Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Soil and Water Conservation as Carbon Sinks in Karst Areas Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Puding County, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Rock Desertification and Soil Data

2.2.2. Meteorological and Remote Sensing Data

| Data Category | Dataset Name/Source | Resolution/Scale | Time Coverage | Purpose in Study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Geography | Rock Desertification Data (2nd Round) | Vector (1:10,000) | 2010, 2017 | Extraction of vegetation and engineering patches | [32] |

| DEM | 12.5 m | 2017 | Slope calculation; topographic analysis | [33] | |

| Meteorology | National Meteorological Information Centre | Station Data | 2010–2022 | Interpolation of rainfall and temperature | [34] |

| Atmospheric Humidity Index | 1 km | 2010–2022 | Environmental factor modelling | [30] | |

| Remote Sensing | MODIS NPP & Vegetation Indices | 500 m | 2010–2022 | Biological carbon fixation estimation | [35] |

| Soil Properties | Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) | 1 km | 2017 | Soil type identification | [36] |

| Soil Organic Carbon Mass Fraction | Plot Data | 2016 | SOC calculation parameters | [29] | |

| Carbon Parameters | China Terrestrial Ecosystem Carbon Density | Tabular Data | 2000–2014 | Reference for carbon density baselines | [31] |

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Methodology for Assessing the Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Soil and Water Conservation

2.3.2. A Method for Calculating the Carbon Sink Volume of Soil and Water Conservation Based on Machine Learning

2.3.3. Method for Predicting Carbon Sink Volume in Soil and Water Conservation

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Soil and Water Conservation Carbon Sink Capacity Results

3.1.1. Overall Carbon Sink Capacity of Soil and Water Conservation in Puding County

3.1.2. Analysis of Outcomes of Vegetative Measures

3.1.3. Analysis of Outcomes of Engineering Measures

3.2. Annual Carbon Sink Capacity Inversion Results Based on Machine Learning

3.2.1. Modelling Factor Screening

3.2.2. Model Validation and Comparison

3.2.3. Inversion Results of Soil and Water Conservation Carbon Sink from 2010 to 2022

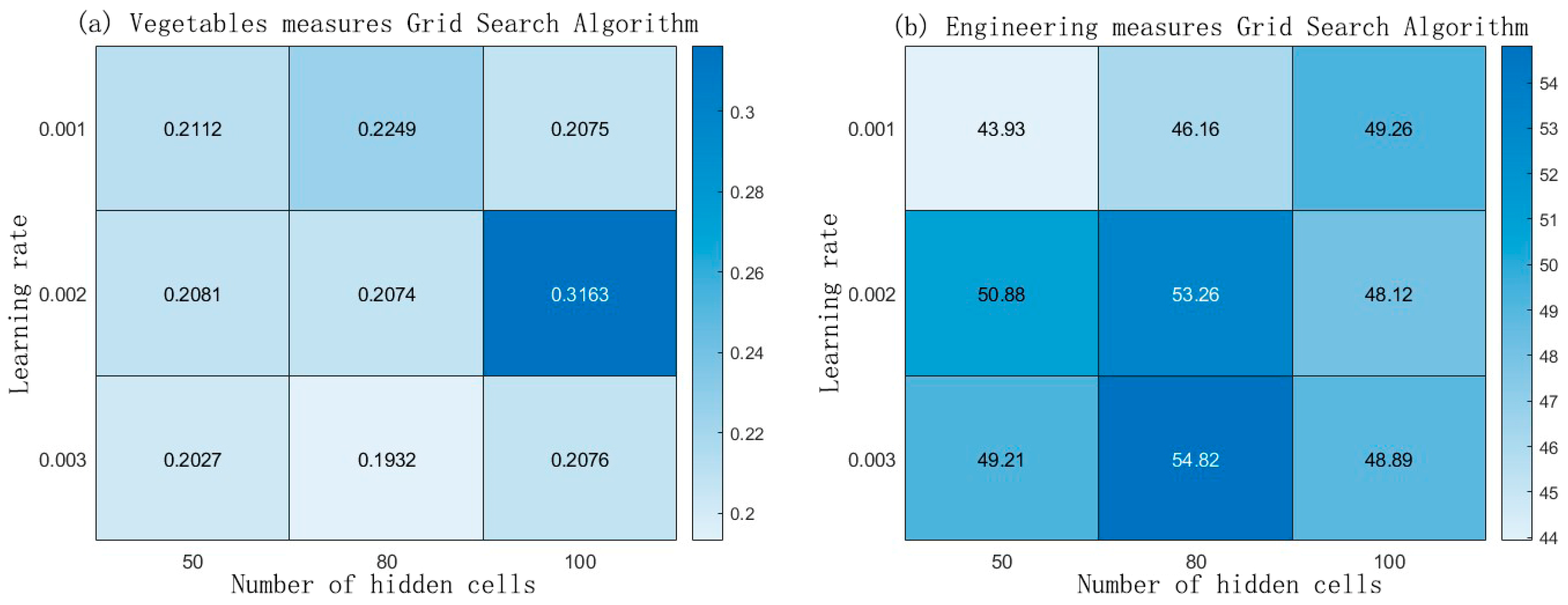

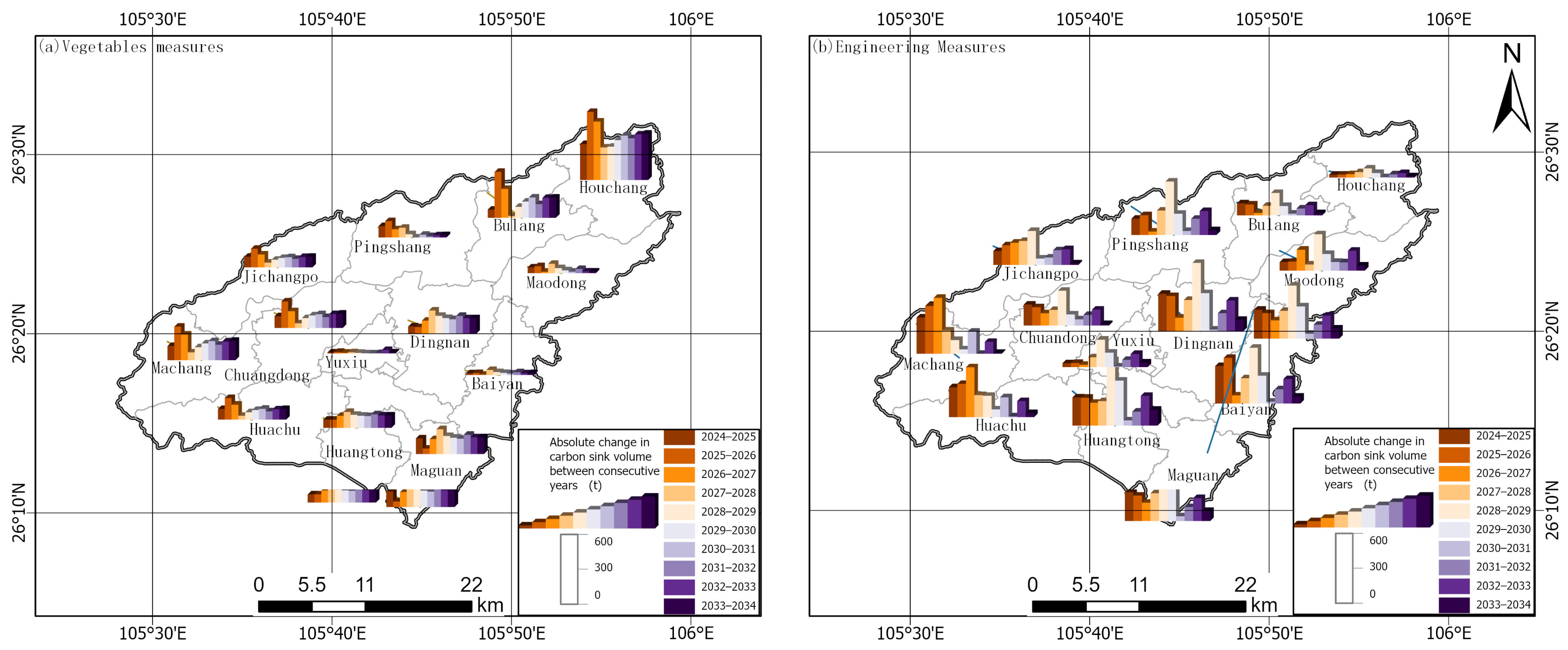

3.3. Projected Soil and Water Conservation Carbon Sink Capacity for 2025–2034

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Limitations

4.2. Uncertainties in the Soil Carbon Sequestration Methodology Framework

4.3. The Application Value of Soil and Water Conservation Carbon Sinks

4.4. Mechanistic Analysis of the Carbon Sink Dominance of Engineering Measures

4.5. Influence of Soil Heterogeneity on Carbon Sink Spatial Patterns

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, J.A.; Chen, S.L. Exploring the Pathways of Achieving Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality Targets in the Provinces of the Yellow River Basin of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.Y.; Zang, L.M.; Schwarz, P.; Yang, H.L. Achieving China’s carbon neutrality goal by economic growth rate adjustment and low-carbon energy structure. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, M.; Lewis, J.; McGlade, C.; Gütschow, J.; Nicholls, Z.; Burdon, R.; Cozzi, L.; Hackmann, B. Realization of Paris Agreement pledges may limit warming just below 2 °C. Nature 2022, 604, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; He, G.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Qi, Y.; Liang, X. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.F.; Mao, J.F.; Bachmann, C.M.; Hoffman, F.M.; Koren, G.; Chen, H.S.; Tian, H.Q.; Liu, J.G.; Tao, J.; Tang, J.Y.; et al. Soil moisture controls over carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions: A review. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiguang, L.; Haiyan, W.; Junxiong, W. Mechanisms, pathways and characteristics of carbon sinks related to soil and water conservation from perspective of carbon peak and carbon neutralization. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 42, 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.L.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.T.; Wang, D.L. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors analysis of fractional vegetation coverage in the arid region of northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Z.M.; Jiang, S.; He, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Li, M.F.; Xing, G.R.; et al. Soil Erosion Characteristics and Scenario Analysis in the Yellow River Basin Based on PLUS and RUSLE Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Mao, X.G. Assessing the effects of China’s Three-North Shelter Forest Program over 40 years. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.H.; Deng, H.; Gao, S.P.; Wang, J.L. Drought Evolution in the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins and Its Dual Impact on Ecosystem Carbon Sequestration. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Were, D.; Kansiime, F.; Fetahi, T.; Hein, T. Carbon Dioxide and Methane Fluxes from a Tropical Freshwater Wetland Under Natural and Rice Paddy Conditions: Implications for Climate Change Mitigation. Wetlands 2021, 41, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Naidu, R.; Dhal, B.; Swain, C.K.; Nayak, A.D.; Tripathi, R.; Shahid, M.; Islam, M.R.; Pathak, H. Current and emerging methodologies for estimating carbon sequestration in agricultural soils: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 890–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Ranalli, M.G.; Haddix, M.L.; Six, J.; Lugato, E. Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenhong, C.; Xiaoming, Z.; Yong, Z.; Bing, L.; Yousheng, W. Connotation of carbon sink in soil and water conservation and its calculation method. Sci. Soiland Water Conserv. 2024, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jincheng, H.; Zaike, G. The Current Situation, Problems and Countermeasures of Soil Erosion in Guizhou Province. China’s Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 8, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Maoqi, N.; Jie, R.; Yu, D.; Songping, L. Exploration and Suggestions on Carbon Sequestration and Emission Reduction Paths for Soil and Water Conservation in Guizhou. China’s Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 6, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jieming, Z.; Guangju, Z.; Qiu, J.; Yonge, Z. A Review of Carbon Sequestration by Soil and Water Conservation Plant Measures. China’s Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 2, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Al Hassan, S.; Jui, M.A.; Gu, L.J.E. Preliminary Comparative Effects of Close-to-Nature and Structure-Based Forest Management on Carbon Sequestration in Pinus tabuliformis Plantations of the Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.H.; Wang, J.X.; Liu, P.L.; Wang, Q.; Han, F.X.; Wang, C.; Sumpradit, T.; Gao, T.P. Key Influencing Factors in the Variation in Livestock Carbon Emissions in the Grassland Region of Gannan Prefecture, China (2009–2024). Agriculture 2025, 15, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamtimin, A.; Amar, G.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Sayit, H.; Gao, J.C.; Zhang, K.; Song, M.Q.; Aihaiti, A.; Wen, C.; et al. Assessment of CO2 fluxes in the hinterland of the Gurbantunggut Desert and its response to climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, W.X.; Dong, H.Y.; Qian, L.W.; Yan, J.F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L. Effects of anthropogenic disturbances on the carbon sink function of Yangtze River estuary wetlands: A review of performance, process, and mechanism. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.X.; Su, M.J.; Kong, L.Q.; Kong, M.L.; Ma, Y.X. Assessing the Economic Value of Carbon Sinks in Farmland Using a Multi-Scenario System Dynamics Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Yong, L.; Songping, L. Calculation of carbon sink capacity of soil and water conservation measures in Guizhou. Sci. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 23, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangqian, W. “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets”: Pathways and prospects for ecological GDP in the Yellow River Basin. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2025, 40, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Yulu, W. Building of an Evaluation IndexSystem for the Quality of Soil and Water Conservation Carbon Sink in the Yellow River Basin. Yellow River 2024, 46, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.L.; Li, Z.X.; Zhang, X.P.; Jian, X.; Wang, D.P. Optimal vegetation coverage from the perspective of ecosystem services in the Qilian Mountains. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 115023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Tang, Y.Q.; Zhou, N.Q.; Wang, J.X.; She, T.Y.; Zhang, X.H. Characteristics of red clay creep in karst caves and loss leakage of soil in the karst rocky desertification area of Puding County, Guizhou, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuelian, D.; Shijie, W.; Qianghui, X.; Tao, P.; Anyun, C.; Lin, Z.; Xianli, C. Evaluation on effect of small catchment comprehensive control in karst rocky desertification areas based on fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method: A case study of the Chenjiazhai catchment in Puding county, Guizhou Province. Carsologica Sin. 2016, 35, 586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Dandan, L.; Xinyu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Shuang, L.; Zhiming, G.; Shuo, L.; Tao, P. A dataset of soil microbial enzyme activities and nitrogen cyclingfunctional genes in Puding County of Guizhou Province. Chin. Sci. Data 2023, 8, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Luo, M.; Zhan, W.F.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.J.; Ge, E.R.; Ning, G.C.; Cong, J. HiMIC-Monthly: A 1 km high-resolution atmospheric moisture index collection over China, 2003–2020. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.X.; Chen, L.K.; Lu, R.; Lou, Z.H.; Zhou, F.R.; Jin, Y.C.; Xue, J.; Guo, H.C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; et al. A national soil organic carbon density dataset (2010–2024) in China. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Ecosystem Science Data Center. Available online: http://www.nesdc.org.cn (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS), Distributed Active Archive Centers (DAACs), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- China Meteorological Science Data Center. Available online: http://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Search NASA’s 1.8 billion+ Earth observations. Available online: https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- National Data Center for Tibetan Plateau Science. Available online: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Fatichi, S.; Pappas, C.; Zscheischler, J.; Leuzinger, S. Modelling carbon sources and sinks in terrestrial vegetation. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.M.; Yang, W.C.; Fu, J.X.; Li, Z. Effects of vegetation and climate on the changes of soil erosion in the Loess Plateau of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lufafa, A.; Tenywa, M.M.; Isabirye, M.; Majaliwa, M.J.G.; Woomer, P.L. Prediction of soil erosion in a Lake Victoria basin catchment using a GIS-based Universal Soil Loss model. Agric. Syst. 2003, 76, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.Q.; Li, G.S. Comprehensive evaluation system for vegetation ecological quality: A case study of Sichuan ecological protection redline areas. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Gong, D.H.; Zhang, L.; Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, D.Y.; Xiao, C.J.; Altan, O. Spatiotemporal dynamics and forecasting of ecological security pattern under the consideration of protecting habitat: A case study of the Poyang Lake ecoregion. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.; Foreman, N.; Knudby, A.; Wu, Y.L.; Lin, Y.W. Global deep learning model for delineation of optically shallow and optically deep water in Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.H.; Wang, Z.M.; Luo, L.; Ren, C.Y. Integrating AVHRR and MODIS data to monitor NDVI changes and their relationships with climatic parameters in Northeast China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 18, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.R.; Zhou, G.S. Estimating green biomass ratio with remote sensing in arid grasslands. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El Monsef, H.; Smith, S.E. A new approach for estimating mangrove canopy cover using Landsat 8 imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 135, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantumur, B.; Wu, F.L.; Vandansambuu, B.; Munaa, T.; Itiritiphan, F.; Zhao, Y. Land Degradation Assessment of Agricultural Zone and Its Causes: A Case Study in Mongolia. In Proceedings of the Conference on Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XX, Berlin, Germany, 10–13 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, J.Q.; Yue, H. Soil respiration estimation in desertified mining areas based on UAV remote sensing and machine learning. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 3433–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radocaj, D.; Jurisic, M. A Phenology-Based Evaluation of the Optimal Proxy for Cropland Suitability Based on Crop Yield Correlations from Sentinel-2 Image Time-Series. Agriculture 2025, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Feng, G. Are soil-adjusted vegetation indices better than soil-unadjusted vegetation indices for above-ground green biomass estimation in arid and semi-arid grasslands? Grass Forage Sci. 2015, 70, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Qin, L.J.; Hao, M.Y.; Zhao, W.L.; Luo, J.Y.; Qiu, X.; Xu, L.J.; Xiong, Y.J.; Ran, Y.L.; Yan, C.H.; et al. An improved approach to estimate above-ground volume and biomass of desert shrub communities based on UAV RGB images. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, J.; Oommen, T.; Thomas, J.; Kasaragod, A.; Dobson, R.; Brooks, C.; Jayakumar, P.; Cole, M.; Ersal, T. Terrain Characterization via Machine vs. Deep Learning Using Remote Sensing. Sensors 2023, 23, 5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, R.X.; Qi, D.F.; Xiong, Y.H. A Novel Methodology for Credit Spread Prediction: Depth-Gated Recurrent Neural Network with Self-Attention Mechanism. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 257865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Gao, F.; Bi, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.J. Ecological Security Pattern Construction in Loess Plateau Areas—A Case Study of Shanxi Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Q.; Ji, Z.Z.; Lu, L.H. A Method for Identifying Key Areas of Ecological Restoration, Zoning Ecological Conservation, and Restoration. Land 2025, 14, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Min, Z.; Yang, M.X.; Yan, J. Exploration of the Implementation of Carbon Neutralization in the Field of Natural Resources under the Background of Sustainable Development-An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi-Murillo, G.; Diels, J.; Gilles, J.; Willems, P. Soil organic carbon in Andean high-mountain ecosystems: Importance, challenges, and opportunities for carbon sequestration. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.J. Ecological and environmental effects of land-use changes in the Loess Plateau of China. Chin. Sci. Bull.-Chin. 2022, 67, 3768–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Chu, X.; Wei, S.; Lian, J.J.E. Predicting Aboveground Carbon Storage in Different Types of Forests in South Subtropical Regions Using Machine Learning Models. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Rakshit, S.; Tikle, S.; Das, S.; Chatterjee, U.; Pande, C.B.; Alataway, A.; Al-Othman, A.A.; Dewidar, A.Z.; Mattar, M.A. Integration of GIS and Remote Sensing with RUSLE Model for Estimation of Soil Erosion. Land 2023, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.I.; Park, W.H.; Shin, Y.; Park, J.W.; Engel, B.; Yun, Y.J.; Jang, W.S. Applications of Machine Learning and Remote Sensing in Soil and Water Conservation. Hydrology 2024, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, K.; Ahmed, A.; Abdellah, A.; Salma, E. Estimation and mapping of water erosion and soil loss: Application of Gavrilovic erosion potential model (EPM) using GIS and remote sensing in the Assif el mal Watershed, Western high Atlas. China Geol. 2024, 7, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Area | Number of Patches (Units) | Administrative Area (km2) | Total Area of Plot (km2) | TCS (∗104 t) | CSD (t/km2) | CSCV (∗104 t) | CSCV_D (t/km2) | CSCE (∗104 t) | CSCE_D (t/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puding County | 1980 | 1079.23 | 321.67 | 34.53 ± 1.32 | 1073.61 | 12.16 ± 0.61 | 1231.52 | 22.37 ± 1.09 | 1003.45 |

| Vegetation Index Factor | Texture Factor | Texture Factor | Meteorological Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ARVI | 1 | B3_Con | 13 | B4_Sec | 1 | Precipitation |

| 2 | DVI | 2 | B3_Cor | 14 | B4_Homo | 2 | Average temperature |

| 3 | EVI | 3 | B3_Diss | 15 | B4_Var | 3 | Highest temperature |

| 4 | MSVI | 4 | B3_Entro | 16 | B4_Mean | 4 | Lowest temperature |

| 5 | NDVI | 5 | B3_Sec | 17 | B5_Con | 5 | Sunshine |

| 6 | NLI | 6 | B3_Homo | 18 | B5_Cor | 6 | Humidity |

| 7 | RVI | 7 | B3_Var | 19 | B5_Diss | 7 | NPP |

| 8 | RVI54 | 8 | B3_Mean | 20 | B5_Entro | ||

| 9 | RVI64 | 9 | B4_Con | 21 | B5_Sec | ||

| 10 | SAVI | 10 | B4_Cor | 22 | B5_Homo | ||

| 11 | B4_Diss | 23 | B5_Var | ||||

| 12 | B4_Entro | 24 | B5_Mean |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Variable | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARVI | 0.063 ** | B3_Sec | 0.185 *** | B5_Cor | 0.108 *** |

| NLI | 0.048 * | B3_Var | 0.148 *** | B5_Entro | 0.062 ** |

| RVI54 | 0.088 *** | B3_Mean | 0.106 *** | B5_Mean | 0.05 * |

| EVI | 0.094 *** | B4_Entro | 0.222 *** | B5_Sec | 0.065 ** |

| B3_Con | 0.117 *** | B4_Homo | 0.193 *** | Precipitation | 0.164 *** |

| B3_Cor | 0.097 *** | B4_Sec | 0.223 *** | Average temperature | 0.05 * |

| B3_Diss | 0.151 *** | B4_Con | 0.162 *** | NPP | 0.053 * |

| B3_Entro | 0.184 *** | B5_Var | 0.122 *** | Sunshine | 0.101 *** |

| B3_Homo | 0.156 *** | B5_Con | 0.127 *** |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Variable | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARVI | 0.317 *** | B3_Entro | 0.091 ** | B5_Diss | 0.28 *** |

| EVI | 0.201 *** | B3_Mean | 0.236 *** | B5_Entro | 0.29 *** |

| NDVI | 0.208 *** | B4_Diss | 0.15 *** | B5_Homo | 0.273 *** |

| RVI | 0.227 *** | B4_Entro | 0.151 *** | B5_Sec | 0.274 *** |

| RVI54 | 0.262 *** | B4_Homo | 0.131 *** | B5_Var | 0.308 *** |

| RVI64 | 0.287 *** | B4_Var | 0.157 *** | B5_Mea | 0.266 *** |

| SAVI | 0.208 *** | B4_Mean | 0.278 *** | B5_Cor | 0.176 *** |

| B3_Con | 0.144 *** | B4_Con | 0.15 *** | precipitation | 0.167 *** |

| B3_Cor | 0.064 * | B4_Cor | 0.112 *** | Average temperature | 0.09 ** |

| Factor Name | Factor Importance |

|---|---|

| B5_Corralation | 17.70% |

| B4_Second_Moment | 16.60% |

| B5_Mean | 13.20% |

| EVI | 12.30% |

| precipitation | 10.20% |

| B5_Contrast | 9.00% |

| RVI54 | 8.00% |

| Average temperature | 7.40% |

| B5_Variance | 5.60% |

| Factor Name | Factor Importance |

|---|---|

| b5_Variance | 20.90% |

| ARVI | 12.70% |

| RVI64 | 11.60% |

| b5_Corralation | 10.40% |

| b3_Entropy | 9.50% |

| precipitation | 8.90% |

| b5_Mean | 7.90% |

| b3_Correlation | 7.20% |

| Average temperature | 6.70% |

| EVI | 4.40% |

| Model | Training Set | Test Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | MAE | RMSE | R2 | MAE | RMSE | |

| Random Forest | 0.56 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.32 |

| ExtraTrees | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.38 |

| CatBoost | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| XGBoost | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| Model | Training Set | Test Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | MAE | RMSE | R2 | MAE | RMSE | |

| ExtraTrees | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.67 |

| Random Forest | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 0.99 |

| CatBoost | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.98 |

| XGBoost | 0.17 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Xie, L.; Dong, R.; Huang, S.; Yang, Q.; Yang, G.; Ma, R.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Z. The Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Soil and Water Conservation as Carbon Sinks in Karst Areas Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Puding County, China. Agriculture 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010015

Li M, Xie L, Dong R, Huang S, Yang Q, Yang G, Ma R, Liu L, Wang T, Zhou Z. The Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Soil and Water Conservation as Carbon Sinks in Karst Areas Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Puding County, China. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Man, Lijun Xie, Rui Dong, Shufen Huang, Qing Yang, Guangbin Yang, Ruidi Ma, Lin Liu, Tingyue Wang, and Zhongfa Zhou. 2026. "The Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Soil and Water Conservation as Carbon Sinks in Karst Areas Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Puding County, China" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010015

APA StyleLi, M., Xie, L., Dong, R., Huang, S., Yang, Q., Yang, G., Ma, R., Liu, L., Wang, T., & Zhou, Z. (2026). The Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Prediction of Soil and Water Conservation as Carbon Sinks in Karst Areas Based on Machine Learning: A Case Study of Puding County, China. Agriculture, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010015