An Economic Analysis of Rice Cultivation Pattern Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

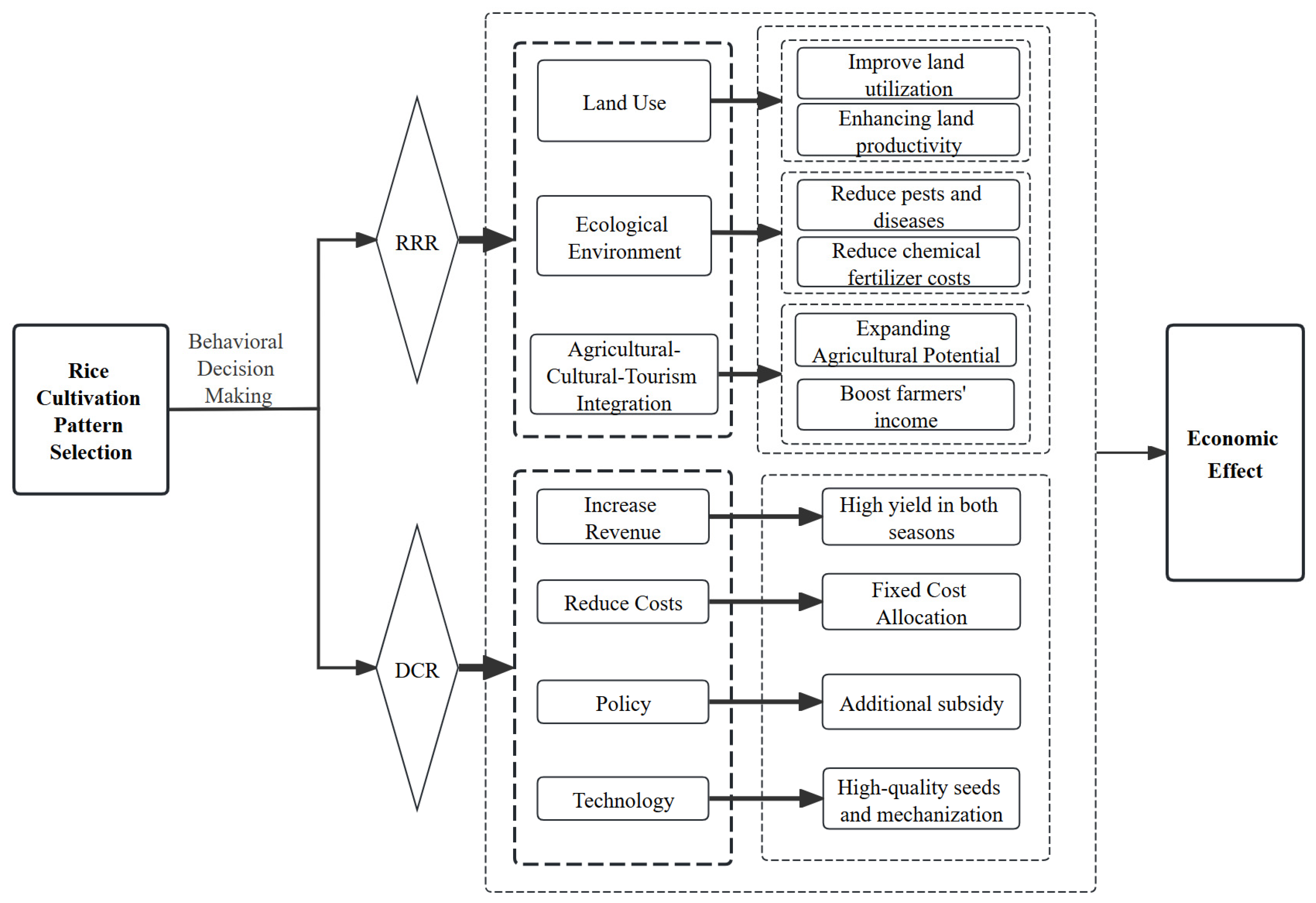

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Economic Effects of Farmers’ Cropping Pattern Choices

2.2. Analysis of Farmers’ Decision-Making Behavior in Cropping Pattern Selection

3. Data Sources, Variable Selection, and Model Specification

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Model Construction

3.3. Variable Selection

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

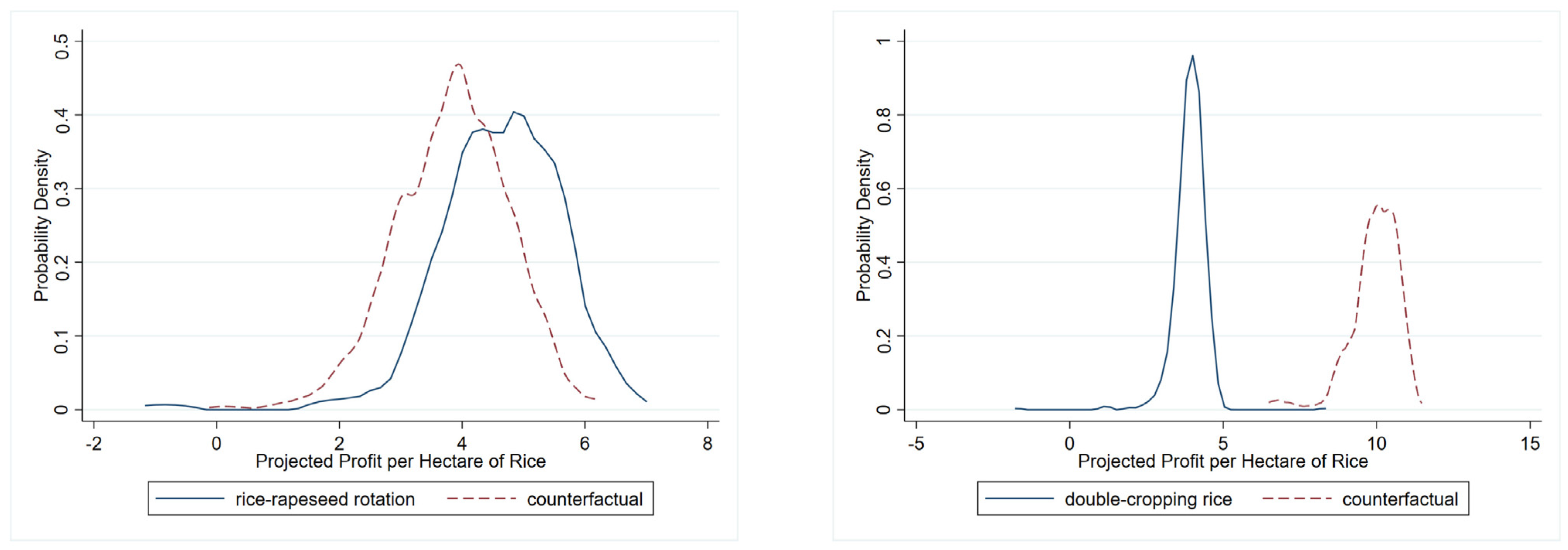

4.1. Analysis Based on the Estimation Results of the Endogenous Switching Regression Model

4.2. Robustness Check

4.2.1. Alternative Estimation Method

4.2.2. Winsorization of Variables

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Heterogeneity in Labor Force Size

4.3.2. Heterogeneity in Farming Generations

4.3.3. Heterogeneity in Rice Cultivation Scale

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mishra, A.; Bruno, E.; Zilberman, D. Compound natural and human disasters: Managing drought and COVID-19 to sustain global agriculture and food sectors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yue, W.; Yang, J.; Xue, B.; Xiao, W.; Li, M.; He, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q. Cropland abandonment in China: Patterns, drivers, and implications for food security. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissteiner, C.J.; Boschetti, M.; Böttcher, K.; Carrara, P.; Bordogna, G.; Brivio, P.A. Spatial explicit assessment of rural land abandonment in the Mediterranean area. Glob. Planet. Change 2011, 79, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Zong, S.; Kleidon, A.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Y.; Shi, P. Impacts of climate warming, cultivar shifts, and phenological dates on rice growth period length in China after correction for seasonal shift effects. Clim. Change 2019, 155, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansanga, M.; Andersen, P.; Kpienbaareh, D.; Mason-Renton, S.; Atuoye, K.; Sano, Y.; Antabe, R.; Luginaah, I. Traditional agriculture in transition: Examining the impacts of agricultural modernization on smallholder farming in Ghana under the new Green Revolution. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, M.S.; Zilberman, D. Economic factors affecting diversified farming systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, M.; Rodrik, D.; Verduzco-Gallo, Í. Globalization, structural change, and productivity growth, with an update on Africa. World Dev. 2014, 63, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, W.; Schraven, B.; Awo, M. Smallholder adaptation to climate change: Dynamics and limits in Northern Ghana. Clim. Change 2012, 111, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Heros, E.; Graterol, E.; Chirinda, N.; Pittelkow, C.M. Balancing Economic and Environmental Performance for Small-Scale Rice Farmers in Peru. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 564418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Verburg, P.H.; Stehfest, E.; Müller, C. The yield gap of global grain production: A spatial analysis. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Veldkamp, A. The role of spatially explicit models in land-use change research: A case study for cropping patterns in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2001, 85, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Shen, Y.; Kong, X.; Ge, B.; Sun, X.; Cao, M. Effects of Diverse Crop Rotation Sequences on Rice Growth, Yield, and Soil Properties: A Field Study in Gewu Station. Plants 2024, 13, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.-C.; Ma, Y.-L.; Li, Z.-Z.; Zhong, C.-S.; Cheng, Z.-B.; Zhan, J. Crop Rotation Enhances Agricultural Sustainability: From an Empirical Evaluation of Eco-Economic Benefits in Rice Production. Agriculture 2021, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.; Brim-DeForest, W.; Linquist, B.; Leinfelder-Miles, M.M.; Espino, L.; Pittelkow, C.M.; Al-Khatib, K. Addressing economic barriers to crop diversification in rice-based cropping systems. NPJ Sustain. Agric. 2025, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.; Fahad, S.; Li, X. Effects of fertilization on crop production and nutrient-supplying capacity under rice-oilseed rape rotation system. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ren, T.; Lei, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J. Tillage and straw-returning practices effect on soil dissolved organic matter, aggregate fraction and bacteria community under rice-rice-rapeseed rotation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 287, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, J.; Pető, K.; Nagy, J. Pesticide productivity and food security. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dai, K.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Cai, D.; Hoogmoed, W.B.; Oenema, O. Dryland maize yields and water use efficiency in response to tillage/crop stubble and nutrient management practices in China. Field Crops Res. 2011, 120, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cramer, G.L.; Wailes, E.J. Production efficiency of Chinese agriculture: Evidence from rural household survey data. Agric. Econ. 1996, 15, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.T. Education and allocative efficiency: Household income growth during rural reforms in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2004, 74, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xin, L.; Wang, Y. How farmers’ non-agricultural employment affects rural land circulation in China? J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhong, F. Demographic change and its impact on farmers’ field production decisions. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 43, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What drives business model adaptation? The impact of opportunities, threats and strategic orientation. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githinji, M.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Muthuri, C.; Speelman, E.N.; Hofstede, G.J. Farmer land-use decision-making from an instrumental and relational perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 63, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Huang, J.; Huang, J.; Ahmad, S.; Nanda, S.; Anwar, S.; Shakoor, A.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, L.; Cao, X.; et al. Rice production under climate change: Adaptations and mitigating strategies. In Environment, Climate, Plant and Vegetation Growth; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 659–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackworth, J. The limits to market-based strategies for addressing land abandonment in shrinking American cities. Prog. Plan. 2014, 90, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, L.; Wang, B.; Xiang, J.; Gao, M.; Fu, Z.; Long, P.; Luo, H.; Huang, C. Conversion from double-season rice to ratoon rice paddy fields reduces carbon footprint and enhances net ecosystem economic benefit. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W. Economic and Environmental Effects of Farmers’ Green Production Behaviors: Evidence from Major Rice-Producing Areas in Jiangxi Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhuang, T.; Zeng, W. Impact of household endowments on response capacity of farming households to natural disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, W.C. Geographic limits to global labor market flexibility: The human resources paradox of the cruise industry. Geoforum 2011, 42, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, E.L.; Carter, S.E. Agrarian change and the changing relationships between toil and soil in Maragoli, Western Kenya (1900–1994). Hum. Ecol. 2000, 28, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, B.; Wang, R. The aging of farmers and its challenges for labor-intensive agriculture in China: A perspective on farmland transfer plans for farmers’ retirement. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 100, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, C.; Haque, M.E.; Bell, R.W.; Thierfelder, C.; Esdaile, R.J. Conservation agriculture for small holder rainfed farming: Opportunities and constraints of new mechanized seeding systems. Field Crops Res. 2012, 132, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmann, R.; Jagadish, S.V.K.; Heuer, S.; Ismail, A.; Redona, E.; Serraj, R.; Singh, R.K.; Howell, G.; Pathak, H.; Sumfleth, K. Climate change affecting rice production: The physiological and agronomic basis for possible adaptation strategies. Adv. Agron. 2009, 101, 59–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Are there too many farms in the world? Labor market transaction costs, machine capacities, and optimal farm size. J. Polit. Econ. 2022, 130, 636–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Definition and Coding | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Rice Profit | Rice profit per unit area (RMB/hectare) | 5170.74 | 58,762.18 |

| Key Explanatory Variable | Rice Cultivation Pattern | 0 = DCR; 1 = RRR | 0.155 | 0.362 |

| Instrumental Variable | Adoption of Rice–Rapeseed | Proportion of other farmers in the same township adopting RRR | 0.158 | 0.214 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | Age | Actual age of household head in 2022 (years) | 58.145 | 10.857 |

| Education Level | Years of formal education received by household head | 2.843 | 0.95 | |

| Health Status | 1 = Very poor; 2 = Poor; 3 = Average; 4 = Good; 5 = Excellent | 3.865 | 0.973 | |

| Household Endowments | Number of Laborers | Number of agricultural laborers in the household | 3.056 | 1.824 |

| Off-farm Employment | Number of household members engaged in both farm and non-farm work | 0.726 | 1.433 | |

| Operational Characteristics | Adoption of Green Technology | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.393 | 0.489 |

| Cooperative Membership | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.251 | 0.434 | |

| Number of Plots | Number of rice production plots managed by household in 2022 | 17.366 | 87.313 | |

| Landholding Size | Actual cultivated area for rice in 2022 (hectares) | 3.142 | 11.131 | |

| Soil Fertility | 1 = Very poor; 2 = Poor; 3 = Average; 4 = Good; 5 = Excellent | 3.386 | 0.823 | |

| Rice Insurance Purchase | 1 = Yes; 0 = No | 0.502 | 0.5 |

| Selection Equation | Outcome Equation (Log Rice Profit) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cultivation Pattern | DCR | RRR |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.004) | (0.012) | (0.028) | |

| Education Level | −0.010 | −0.128 | 0.067 |

| (0.049) | (0.138) | (0.314) | |

| Health Status | −0.029 | 0.049 | −0.037 |

| (0.045) | (0.125) | (0.259) | |

| Number of Off-farm Workers | −0.168 ** | −0.009 | 0.026 |

| (0.085) | (0.065) | (0.125) | |

| Number of Off-farm Workers | −0.126 | 0.142 * | −0.078 |

| (0.099) | (0.082) | (0.240) | |

| Green Technology Adoption | 0.003 | −0.049 | 0.509 |

| (0.022) | (0.239) | (0.541) | |

| Cooperative Membership | −0.002 | −0.304 | −0.498 |

| (0.033) | (0.277) | (0.700) | |

| Number of Plots | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Landholding Size | 0.001 * | −0.002 * | −0.001 |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Soil Fertility | 0.175 *** | 0.487 *** | 0.913 ** |

| (0.051) | (0.142) | (0.357) | |

| Rice Insurance Purchase | 0.107 | 0.376 | −0.562 |

| (0.085) | (0.240) | (0.510) | |

| Constant | −1.729 *** | 3.230 *** | 0.991 |

| (0.423) | (1.193) | (3.735) | |

| Adoption of Rotation | 0.662 *** | ||

| (0.119) | |||

| lns | 1.278 *** | 1.031 *** | |

| (0.026) | (0.075) | ||

| LR Test | chi2(2) =22.16 Prob > chi2 = 0.023 | ||

| N | 1014 | 857 | 157 |

| Farmer Group | RRR | DCR | ATT | ATU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 4.625 | 3.841 | 0.784 *** | |

| DCR | 9.933 | 3.923 | 6.010 *** |

| Variable | Economic Effect (OLS) |

|---|---|

| RRR | 0.763 *** |

| (0.266) | |

| Control Variables | Controlled |

| Constant Term | 3.114 |

| (0.980) | |

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.051 |

| Sample Size | 1014 |

| Dependent Variable: Log of Rice Profit | (1) Economic Effect | (2) Economic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | |

| Rice Cultivation Pattern | 0.779 *** (0.258) | 0.861 *** (0.251) |

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| Prob > F | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| R-squared | 0.053 | 0.075 |

| Sample Size | 1014 | 1014 |

| Variable | Economic Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| <=3 | >3 | |

| RRR | 0.593 * (0.349) | 0.980 ** (0.421) |

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| Prob > F | 0.018 | 0.001 |

| R-squared | 0.041 | 0.079 |

| Sample Size | 590 | 424 |

| Variable | Economic Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| Born <= 1980 | Born > 1980 | |

| RRR | 0.718 *** (0.276) | 1.454 (1.094) |

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| Prob > F | 0.000 | 0.717 |

| R-squared | 0.052 | 0.107 |

| Sample Size | 928 | 86 |

| Variable | Economic Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <=0.2 Hectare | 0.2–0.7 Hectare | >=0.7 Hectare | |

| RRR | 1.489 *** (0.469) | 0.812 * (0.487) | 0.288 (0.439) |

| Control Variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Prob > F | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.269 |

| R-squared | 0.086 | 0.087 | 0.048 |

| Sample Size | 361 | 347 | 306 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M. An Economic Analysis of Rice Cultivation Pattern Selection. Agriculture 2026, 16, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010129

Wu W, Zhou L, Zhang M. An Economic Analysis of Rice Cultivation Pattern Selection. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Weiguang, Li Zhou, and MengLing Zhang. 2026. "An Economic Analysis of Rice Cultivation Pattern Selection" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010129

APA StyleWu, W., Zhou, L., & Zhang, M. (2026). An Economic Analysis of Rice Cultivation Pattern Selection. Agriculture, 16(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010129