The Effect of Cutting Technique on the Degree of Damage to Fruit Tree Shoots

Abstract

1. Introduction

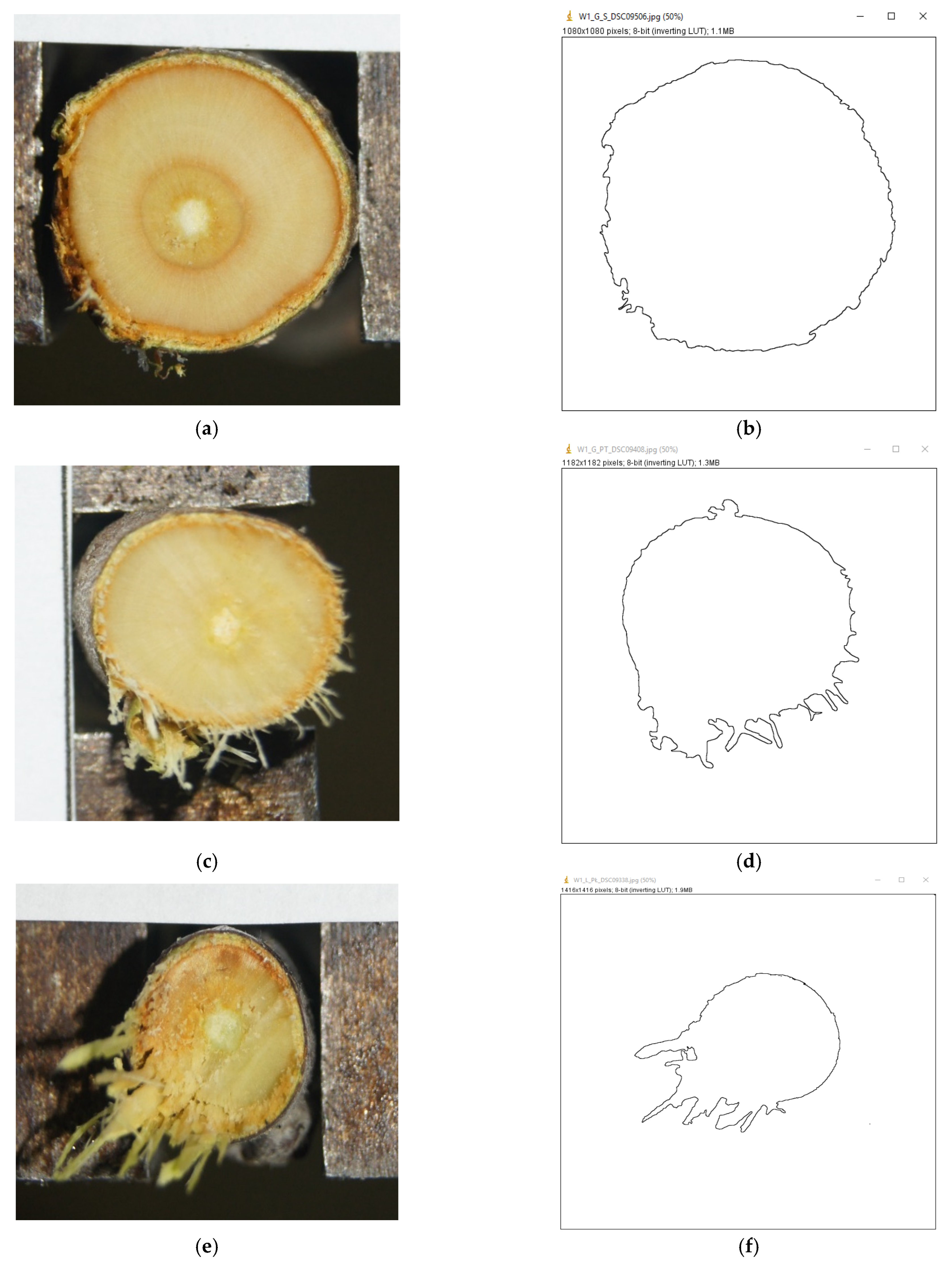

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Material

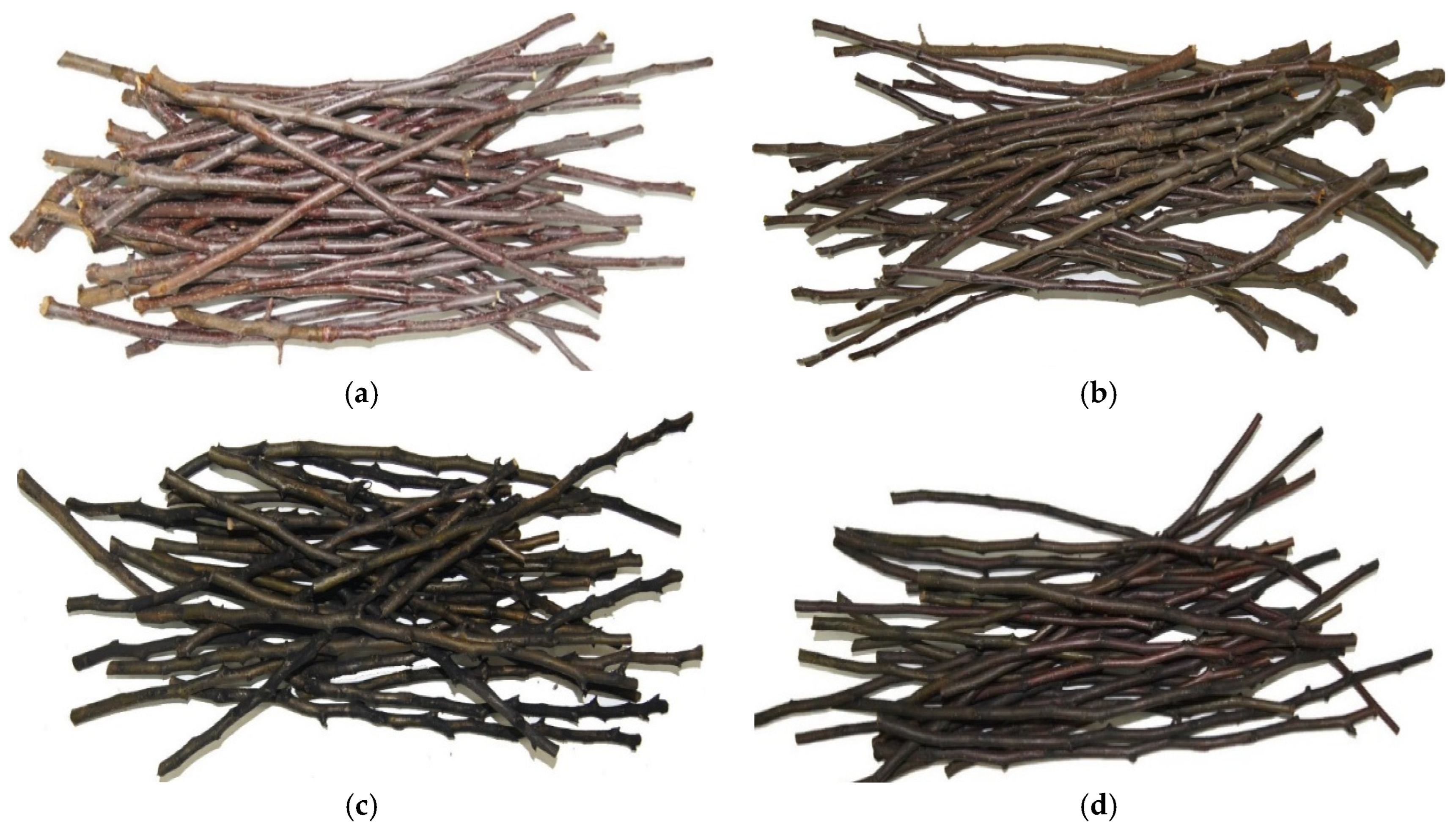

- a 12-year-old ‘Ligol’ apple tree grafted on the ‘P60’ rootstock, planted at 1.2 m within rows and 3.5 m between rows (Figure 1a);

- a 12-year-old ‘Gloster’ apple tree grafted on the ‘M9’ rootstock, planted at 1.2 m within rows and 3.5 m between rows (Figure 1b);

- a 12-year-old ‘Conference’ pear tree grafted on the ‘Caucasian pear’ rootstock, planted at 2.0 m within rows and 3.8 m between rows (Figure 1c);

- a 12-year-old ‘Hortensia’ pear tree grafted on the ‘Caucasian pear’ rootstock, planted at 2.0 m within rows and 3.8 m between rows (Figure 1d).

2.2. Test Stand

2.3. Methodology

3. Results

4. Analysis and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barda, M.S.; Karamaouna, F.; Kati, V.; Stathakis, T.I.; Economou, L.P.; Perdikis, D.C. Flowering Plant Patches to Support the Conservation of Natural Enemies of Pests in Apple Orchards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, P.; Hocevar, M.; Stajnko, D.; Belsak, A. Development of Alternative Plant Protection Product Application Techniques in Orchards, Based on Measurement Sensing Systems: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 124, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, L.; Nari, L.; Nari, D.; Bossolasco, A.; Blanc, S.; Brun, F. Sustainability Analysis of Apple Orchards: Integrating Environmental and Economic Perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Hu, C.; He, Y.; Mhamed, M.; Li, X.; Dong, H.; Saha, C.K.; et al. Key Technologies in Apple Harvesting Robot for Standardized Orchards: A Comprehensive Review of Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, B.; Khabbaz Jolfaee, H.; Mohammadpour, K.; Seilsepour, M.; Dehghanisanij, H.; Hajnajari, H.; Farazmand, H.; Atri, A. Internet of Things-Based Smart System for Apple Orchards Monitoring and Management. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawikhum, K.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Heinemann, P. Development of a Machine Vision System for Apple Bud Thinning in Precision Crop Load Management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide Zaragoza, C.; González Perea, R.; Fernández García, I.; Camacho Poyato, E.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Open Source Application for Optimum Irrigation and Fertilization Using Reclaimed Water in Olive Orchards. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaga Priya, P.; Reethika, A.; Vijaykumar, G.; James Deva Koresh, H. Robotics-Assisted Precision and Sustainable Irrigation, Harvesting, and Fertilizing Processes. In Hyperautomation in Precision Agriculture; Singh, S., Sood, V., Srivastav, A.L., Ampatzidis, Y., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Leng, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q. Optimizing Irrigation and Fertilization at Various Growth Stages to Improve Mango Yield, Fruit Quality and Water-Fertilizer Use Efficiency in Xerothermic Regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Sharma, J.C.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, R.; Ananthakrishnan, S.; Hashem, A.; Almutairi, K.F.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Optimizing Leaf Nutrient Status, Growth, and Yield Parameters in High-Density Apple Orchards (cv. Super Chief) via Integrated Drip Irrigation and Fertigation Techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ju, C.; Bao, F. A Support Vector Model of Pruning Trees Evaluation Based on OTSU Algorithm. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.03638. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, A. Cięcie Drzew i Krzewów Owocowych (Cutting Fruit Trees and Shrubs); Wydawnictwo PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Pieniążek, S. Sadownictwo (Fruit-Growing); Wydawnictwo PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 2000; p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- Allegro, G.; Martelli, R.; Valentini, G.; Pastore, C.; Mazzoleni, R.; Pezzi, F.; Filippetti, I. Effects of Mechanical Winter Pruning on Vine Performances and Management Costs in a Trebbiano Romagnolo Vineyard: A Five-Year Study. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueca, P.; Mateu, G.; Garcerá, C.; Fonte, A.; Ortiz, C.; Torregrosa, A. Yield and Economic Results of Different Mechanical Pruning Strategies on “Navel Foyos” Oranges in the Mediterranean Area. Agriculture 2021, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinxing, L.; Buwen, L.; Hui, L. Pruning decision system for apple tree based on local point cloud and BP neural network. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszela, K. Computer Image Analysis and Artificial Neural Networks in the Qualitative Assessment of Agricultural Products. Agric. Eng. 2015, 3, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, G.; Caballero, P.; Torregrosa, A.; Segura, B.; Juste, F.; Chueca, P. Análisis de la influencia de las operaciones de cultivo sobre los costes de producción en la citricultura de la Comunidad Valenciana. Levante Agrícola Rev. Int. Cítricos 2018, 440, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez, J.A.G. The Effects of Mechanical Pruning on Yield, Fruit Quality and Vegetative Growth in Apple and Sweet Cherry. Ph.D. Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA, 2016; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Niederholzer, F.; Jarvis-Shean, K.; Lightle, D.; Milliron, L.; Stewart, D.; Summer, D.A. Sample Costs to Establish an Orchard and Produce Prunes; University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE), UC Agriculture and Natural Resources (UC ANR), UC Davis: Sacramento Valley, CA, USA, 2018; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, B.; González, E. The influence of mechanical pruning in cost reduction, production of fruit, and biomass waste in citrus orchards. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2010, 26, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Falcão, J.; Pinheiro, A.; Peça, J. Effect of Mechanical Pruning on Olive Yield in a High-Density Olive Orchard: An Account of 14 Years. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; López-Granados, F.; de Castro, A.I.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Serrano, N.; Peña, J.M. Quantifying pruning impacts on olive tree architecture and annual canopy growth by using UAV-based 3D modelling. Plant Methods 2017, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinelli, D.; Onorati, L.; Ruffolo, M.; Tombesi, A. Mechanical Pruning of Adult Olive Trees and Influence on Yield and on Efficiency of Mechanical Harvesting. Acta Hortic. 2011, 924, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, F.; Roccuzzo, G. Modern Trends of Citrus Pruning in Italy. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 25, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gorriz, B.; Porras Castillo, I.; Torregrosa, A. Effect of mechanical pruning on the yield and quality of ‘Fortune’ mandarins. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, A.; Torregrosa, A.; Garcerá, C.; Mateu, G.; Chueca, P. Mechanical Pruning of ‘Clemenules’ Mandarins in Spain: Yield Effects and Economic Analysis. Agronomy 2022, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gorriz, B.; Martínez-Barba, C.; Torregrosa, A. Lemon trees response to different long-term mechanical and manual pruning practices. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 275, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, A.; Buler, Z.; Treder, W. Mechanical pruning of apple trees as an alternative to manual pruning. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2016, 15, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, J.; Schwender, C. Mechanical pruning in organic apple production—Especially with regard to pathogens and pests. In Proceedings of the Ecofruit: 17th International Conference on Organic Fruit-Growing, Hohenheim, Germany, 15–17 February 2016; pp. 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Miljan, C.; Cvijanović, J.S. Mechanical plum pruning. J. Agric. Food Environ. Sci. 2022, 76, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekitkan, F.G. Mechanical properties of Okuzgozu (Vitis vinifera L. cv.) grapevine canes. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.R.; Nuñes, P.R.; Santos, S.L.; Teixeira, L.J.; Araújo, A.R.; Cavalcante, L.I.H. Impact of First Mechanical Fructification Pruning on Mango Orchards. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2021, 21, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekitkan, F.G.; Eliçin, A.K.; Sessiz, A. Bazı yerli tip üzüm (Vitis vinifera L.) çeşitlerinin budama sürgünlerinin kesme özelliklerinin belirlenmesi. ÇOMÜ Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2020, 8, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosecrance, R.; Milliron, L.; Niederholzer, F. Mechanical pruning of ‘Improved French’ prune trees. Acta Hortic. 2021, 1322, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcia, F.; Prieto, J.; Trentacoste, E.R. Effects of Mechanical Box Pruning Intensity on Bud Development, Vegetative Growth, and Yield Components on cv. Cabernet-Sauvignon in Mendoza, Argentina. OENO One 2023, 57, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, T.; Tucki, K. Impact of blade geometric parameters on the specific cutting energy of willow (Salix viminalis) stems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsik, R.; Michalec, K. Image analysis in wood testing—Selected examples. Agric. Eng. 2016, 20, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber, R.; Łasecki, M.; Kuczyński, K.; Cebryk, R.; Kwaśnicka, J.; Olchowy, C.; Łach, K.; Pogodajny, Z.; Koptiuk, O.; Olchowy, A.; et al. Hounsfield Units and Fractal Dimension (Test HUFRA) for Determining PET Positive/Negative Lymph Nodes in Pediatric Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, M.S.; Rabelo, G.D.; Spin-Neto, R.; Dechichi, P.; Borges, J.S.; Soares, P.B.F. Use of Micro-Computed Tomography for Bone Evaluation in Dentistry. Braz. Dent. J. 2018, 29, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losa, G.A. The Living Realm Depicted by the Fractal Geometry. Fractal Geom. Nonlinear Anal. Med. Biol. 2015, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2003; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- ASABE Standards 2011; Moisture Measurement—Forages ASABE S358.2 (R2008). American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2011; pp. 780–781.

- Kruczyńska, D. Nowe Odmiany Jabłoni; Hortpress: Warszawa, Poland, 2008; pp. 110–180. ISBN 978-83-8921-149-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ugolik, M. Odmiany Jabłoni; Plantpress: Kraków, Poland, 1996; pp. 44–86. ISBN 83-85982-11-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, E.; Ozimek, E.; Sobiczewski, P.; Słomka, A.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Effect of Pseudomonas luteola on mobilization of phosphorus and growth of young apple trees (Ligol)—Pot experiment. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 164, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuolienė, G.; Viškelienė, A.; Sirtautas, R.; Kviklys, D. Relationships between apple tree rootstock, crop-load, plant nutritional status and yield. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 211, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewski, B.; Kopytowski, J. Effects of some soil cultivation methods on the growth and yielding of apple trees grafted on semi-dwarf rootstocks and ‘Antonowka’ seedling with B 9 interstock. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Sadow. I Kwiaciarstwa 2008, 16, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Klimek, K.E.; Kapłan, M.; Najda, A.B. Effect of growth regulators on quality of apple tree maidens. Acta Agrophys. 2018, 25, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapłan, M.; Klimek, K.E.; Buczyński, K. Analysis of the Impact of Treatments Stimulating Branching on the Quality of Maiden Apple Trees. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodun, G. Evaluation of the Occurrence of Old Trees and Variety Identification in the Mountain Area and the Izer Mountains. 2018. Available online: http://2018.lgdpartnerstwoizerskie.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Studium-o-odmianach_CALOSC.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Łysiak, G. Uprawa i Odmiany Gruszy; Hortpress: Warszawa, Poland, 2006; p. 156. ISBN 83-89211-18-1. [Google Scholar]

- Terzoudis, K.; Kusma, R.; Hertog, M.L.A.T.M.; Nicolaï, B.M. Metabolic adaptation of ‘Conference’ pear to postharvest hypoxia: The impact of harvest time and hypoxic pre-treatments. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 189, 111937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, P.; Diels, J.; Vanderborght, J.; Elsen, F.; Elsen, A.; Deckers, T.; Vandendriessche, H. Numerical calculation of soil water potential in an irrigated ‘Conference’ pear orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 148, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.; Marcelo, V.; Casquero, P.A. Postharvest quality enhancement in high-russet ‘Conference’ pears: The role of organic farming and edible coatings. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 229, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadulski, R.; Wróblewska-Barwińska, K.; Strzałkowska, K. Experimental characteristic of textural properties of the selected varieties of pears. Agric. Eng. 2012, 16, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kolniak-Ostek, J. Identification and quantification of polyphenolic compounds in ten pear cultivars by UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 49, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parts, Instructions, and Technical Support for 436Li. Available online: https://www.husqvarna.com/pl/wsparcie/436li/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Nevrkla, P.; Staněk, L.; Neruda, J. Analysis of Selected Functional Parameters of Saw Chains. J. For. Sci. 2025, 71, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poje, A.; Mihelič, M. Influence of Chain Sharpness, Tension Adjustment and Type of Electric Chainsaw on Energy Consumption and Cross-Cutting Time. Forests 2020, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandur, Z.; Bačić, M.; Šušnjar, M.; Landekić, M.; Šporčić, M.; Jambreković, B.; Lepoglavec, K. Energy Consumption and Cutting Performance of Battery-Powered Chainsaws. Forests 2023, 14, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dado, M.; Kučera, M.; Salva, J.; Hnilica, R.; Hýrošová, T. Influence of Saw Chain Type and Wood Species on the Mass Concentration of Airborne Wood Dust during Cross-Cutting. Forests 2022, 13, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliniewicz, Z.; Maleszewski, Ł.; Krzysiak, Z. Influence of Saw Chain Type and Wood Species on the Kickback Angle of a Chainsaw. Tech. Sci. 2018, 21, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauske, E.; Fuder, J.; Rains, G. Chainsaw Chains and Bars. CAES Field Report 2025. Available online: https://fieldreport.caes.uga.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/C-1208_4.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Maciak, A.; Kubuśka, M. The Influence of Initial Tension on Blunting of Chainsaw Blades and Cutting Efficiency. For. Res. Pap. 2018, 79, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, W.; Nevrkla, P. Assessment of Portable Chainsaw Chains. Arboric. J. 2020, 42, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciak, A.; Kubuśka, M.; Moskalik, T. Instantaneous Cutting Force Variability in Chainsaws. Forests 2018, 9, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KS 216 M. Available online: https://www.metabo.com/com/en/tools/sawing/mitre-saws/ks-216-m-mitre-saw/610216000 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Metabo GmbH. KS 216 M Lasercut Operating Instructions and Technical Data. Available online: https://manuals.plus/metabo/ks-216-m-lasercut-crosscut-saw-manual (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Metabo GmbH. Metabo Service Portal—KS 216 M Lasercut Manual Search. Available online: https://www.metabo-service.com/en/manual/19216190 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Frezwid. Types of Blades: HM, HW—Cemented Carbide, What Is It? Available online: https://frezwid.com.pl/poradnik/rodzaje-ostrzy/hm-hw-widia-weglik-spiekany-co-to-takiego (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- ISprzet. Cemented Carbide—Properties and Applications. Available online: https://www.isprzet.pl/pl/blog/weglik-spiekany.html (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Orłowski, K.; Ochrymiuk, T. Dynamics of cutting power during sawing with circular saw blades as an effect of wood properties changes in the cross section. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci.—SGGW For. Wood Technol. 2013, 83, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gołombek, K.; Dobrzański, L.A. Hard and Wear Resistance Coatings for Cutting Tools. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2007, 24, 24221. Available online: http://jamme.acmsse.h2.pl/papers_vol24_2/24221.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- ASM International. ASM Handbook: Properties and Selection of Carbides; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskars L28 Hook typ S. Available online: https://www.fiskars.com/en-gb/gardening/products/loppers (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Nowakowski, T.; Dąbrowska, M.; Sypuła, M.; Strużyk, A. A method for evaluating the size of damages to fruit trees during pruning using different devices. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 242, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafalski, M.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Application of fractal dimension and texture analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment of a venous lake in the oral mucosa using a 980 nm diode laser: A preliminary study. Materials 2021, 14, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, J.; Magdziarczyk, J.; Wojnar, L. Analiza Fraktalna Struktury Geometrycznej Powierzchni. In Innowacje w Zarządzaniu i Inżynierii Produkcji; Konferencja: Zakopane, Poland, 2011; pp. 382–396. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, C.H.; Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals in Geophysics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Singh, A.K.; Kolan, S.R.; Tsotsas, E. Fractal analysis of aggregates: Correlation between the 2D and 3D box-counting fractal dimension and power law fractal dimension. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 160, 112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losa, G.A.; Ristanović, D.U.; Ristanović, D.E.; Zaletel, I.; Beltraminelli, S. From Fractal Geometry to Fractal Analysis. Appl. Math. 2016, 7, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ieva, A.; Grizzi, F.; Jelinek, H.; Pellionisz, A.J.; Losa, G.A. Fractals in the Neurosciences, Part I: General Principles and Basic Neurosciences. Neuroscientist 2013, 19, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Koc, A.B.; Wang, X.N.; Jiang, Y.X. A review of pruning fruit trees. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 153, 062029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrulhisham, N.; Othman, N. Knowledge in Tree Pruning for Sustainable Practices in Urban Setting: Improving Our Quality of Life. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2017, 234, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, T.; Nowakowski, M. Assessment of tree sprouts pruning with various types of cutting units. Agric. Eng. 2018, 22, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, E.; Neri, F.; Fioravanti, M.; Picchio, R.; Goli, G.; Di Giulio, G. Effects of Cutting Patterns of Shears on Occlusion Processes in Pruning. Croat. J. For. Eng. 2013, 34, 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Safvati, M.; Minaei, S.; Mahdavian, A. Comparative analysis of fractal dimension and novel geometric indices for assessing branch cutting quality. Measurement 2025, 248, 116941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Unit | Mean | Min * | Max * | Median | Standard Deviation | CV * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hortensia | Length | cm | 39.2 | 18.0 | 64.0 | 37.5 | 13.2 | 33.6 |

| Diameter | mm | 9.33 | 6.99 | 12.51 | 9.16 | 1.48 | 15.88 | |

| Conference | Length | cm | 31.5 | 19.0 | 47.0 | 32.0 | 7.2 | 23.0 |

| Diameter | mm | 8.16 | 6.76 | 10.22 | 7.99 | 0.84 | 10.25 | |

| Ligol | Length | cm | 42.3 | 26.0 | 56.0 | 43.0 | 8.3 | 19.6 |

| Diameter | mm | 9.94 | 7.91 | 13.46 | 9.78 | 1.36 | 13.67 | |

| Gloster | Length | cm | 39.3 | 20.0 | 63.0 | 39.5 | 13.4 | 34.0 |

| Diameter | mm | 9.28 | 7.58 | 12.63 | 8.99 | 1.22 | 13.14 | |

| Category | Parameter | Value/Description | Technical Significance and Literature Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain geometry | Pitch | 3/8″ | The pitch determines the spacing of the cutting teeth and the dynamic load characteristics during cutting. Chains with a 3/8″ mini pitch are commonly used in electric and battery-powered chainsaws due to their lower torque demand and reduced vibration levels [59,60]. |

| Guide bar groove width (gauge) | 1.1 mm | A smaller drive link thickness results in a narrower kerf, reducing cutting resistance and energy demand, which is particularly important for battery-powered devices [61]. | |

| Cutter profile type | Chamfer Chisel | The semi-chisel (chamfered) profile represents a compromise between cutting aggressiveness and edge durability. Literature indicates that chamfer chisel cutters exhibit higher resistance to dulling and lower kickback risk compared to full chisel profiles [62,63]. | |

| Vibration and kickback reduction | Yes (low-kickback design) | The use of ramped depth gauges and PIXEL-type geometry reduces kickback risk and vibration transmitted to the operator, improving ergonomics and occupational safety [64]. | |

| Geometrical variants | Guide bar length/number of drive links | 25 cm/40 drive links | Shorter guide bars provide higher cutting precision and lower moment of inertia, which is advantageous in tree maintenance operations and cutting small-diameter shoots [65]. |

| 30 cm/45 drive links | The most commonly used configuration in compact chainsaws, offering a balance between cutting reach and operational stability [60]. | ||

| 35 cm/52 drive links | Provides greater cutting depth, but at the cost of increased dynamic and energy loads [61]. | ||

| Material construction | Chain body | Structural alloy steel | The drive links, tie straps, and rivets are manufactured from alloy steel with enhanced fatigue strength and abrasion resistance. Studies indicate that the material properties of the chain body significantly affect fatigue life and overall durability [66]. |

| Cutting teeth—material | Alloy steel | The cutting teeth are made from the same base alloy steel as the chain body but are subjected to additional processing. Material homogeneity reduces the risk of cracking at the tooth–link interface [67]. | |

| Cutting teeth—treatment | Heat hardening/surface hardening | Thermal hardening increases the hardness of the cutting edge, improves wear resistance, and extends the service life between sharpening cycles. Literature confirms that this process significantly affects cutting efficiency and energy consumption [63,66]. |

| Category | Parameter | Value/Description | Technical Significance and Literature Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic dimensions | Diameter × cutting width × bore | 216 × 2.4 × 30 mm | Standard dimensions for 216 mm circular saw blades; determines cutting depth, compatibility with various saw models, and kerf width. Suitable for compact and stationary circular saws [69,70]. |

| Number of teeth | Teeth count | 40 | Number of teeth affects cutting speed, smoothness, and material removal rate. Higher tooth count generally produces smoother cuts, but may increase cutting resistance [70,71]. |

| Tooth shape | WZ (alternating bevel) | Alternating bevel geometry (left/right) with 5° negative rake angle | Provides balanced cutting action, reduced vibration, and safer operation. WZ teeth are common for cross-cutting wood [71,72]. |

| Blade body thickness | Thickness | 1.8 mm | Determines rigidity and stability during cutting. Thicker body reduces vibration but slightly increases kerf and energy demand [72]. |

| Rake angle | Cutting edge angle | −5° (negative) | Negative rake improves control, reduces tear-out in cross-cutting, and lowers feed force, enhancing safety and surface finish [72,73]. |

| Material | Teeth and body | HW/CT cemented carbide (WC + TiC bonded with Co) | HW/CT is a very hard and wear-resistant material. Tungsten carbide (WC) and titanium carbide (TiC) form the hard phase, while cobalt (Co) acts as a metallic binder, providing toughness. Material selection directly affects tool life and cutting efficiency [74,75]. |

| Compatible saw models | Applications | KS 216 M Lasercut, KGS 216 M, KGSV 216 M, KGSV 72 Xact, KGSV 72 Xact SYM | Blade dimensions and arbor design compatible with multiple 216 mm Metabo saw models, ensuring interchangeability and operational flexibility [69,70]. |

| MC | Cutting Units | Tree | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Standard Deviation | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC1 | PL | G | 1.160 | 1.146 | 1.132 | 1.215 | 0.029 | 2.527 |

| H | 1.166 | 1.164 | 1.133 | 1.196 | 0.017 | 1.418 | ||

| K | 1.161 | 1.157 | 1.136 | 1.183 | 0.018 | 1.538 | ||

| L | 1.160 | 1.156 | 1.133 | 1.190 | 0.021 | 1.805 | ||

| PT | G | 1.152 | 1.141 | 1.119 | 1.211 | 0.031 | 2.683 | |

| H | 1.136 | 1.136 | 1.119 | 1.155 | 0.010 | 0.917 | ||

| K | 1.150 | 1.143 | 1.133 | 1.203 | 0.020 | 1.748 | ||

| L | 1.149 | 1.152 | 1.122 | 1.188 | 0.021 | 1.821 | ||

| S | G | 1.144 | 1.143 | 1.131 | 1.155 | 0.008 | 0.728 | |

| H | 1.141 | 1.142 | 1.129 | 1.160 | 0.009 | 0.785 | ||

| K | 1.147 | 1.145 | 1.116 | 1.204 | 0.024 | 2.058 | ||

| L | 1.155 | 1.157 | 1.132 | 1.175 | 0.013 | 1.113 | ||

| MC2 | PL | G | 1.168 | 1.169 | 1.147 | 1.194 | 0.016 | 1.335 |

| H | 1.180 | 1.183 | 1.149 | 1.208 | 0.019 | 1.573 | ||

| K | 1.196 | 1.189 | 1.162 | 1.271 | 0.033 | 2.718 | ||

| L | 1.166 | 1.172 | 1.141 | 1.188 | 0.017 | 1.492 | ||

| PT | G | 1.155 | 1.151 | 1.132 | 1.191 | 0.020 | 1.763 | |

| H | 1.149 | 1.148 | 1.123 | 1.178 | 0.016 | 1.362 | ||

| K | 1.150 | 1.150 | 1.125 | 1.173 | 0.012 | 1.073 | ||

| L | 1.140 | 1.140 | 1.114 | 1.161 | 0.015 | 1.359 | ||

| S | G | 1.150 | 1.146 | 1.131 | 1.177 | 0.017 | 1.442 | |

| H | 1.156 | 1.160 | 1.125 | 1.180 | 0.017 | 1.488 | ||

| K | 1.160 | 1.159 | 1.125 | 1.197 | 0.019 | 1.662 | ||

| L | 1.141 | 1.137 | 1.127 | 1.159 | 0.012 | 1.075 | ||

| MC3 | PL | G | 1.188 | 1.185 | 1.166 | 1.227 | 0.019 | 1.596 |

| H | 1.184 | 1.182 | 1.150 | 1.225 | 0.021 | 1.734 | ||

| K | 1.181 | 1.186 | 1.158 | 1.204 | 0.016 | 1.338 | ||

| L | 1.173 | 1.173 | 1.136 | 1.212 | 0.019 | 1.636 | ||

| PT | G | 1.149 | 1.147 | 1.131 | 1.172 | 0.012 | 1.010 | |

| H | 1.158 | 1.157 | 1.127 | 1.201 | 0.024 | 2.073 | ||

| K | 1.150 | 1.154 | 1.113 | 1.170 | 0.016 | 1.405 | ||

| L | 1.152 | 1.150 | 1.140 | 1.182 | 0.012 | 1.080 | ||

| S | G | 1.139 | 1.143 | 1.111 | 1.172 | 0.018 | 1.608 | |

| H | 1.155 | 1.151 | 1.134 | 1.206 | 0.021 | 1.792 | ||

| K | 1.145 | 1.139 | 1.119 | 1.178 | 0.018 | 1.583 | ||

| L | 1.139 | 1.139 | 1.118 | 1.169 | 0.015 | 1.287 | ||

| MC4 | PL | G | 1.182 | 1.189 | 1.150 | 1.210 | 0.021 | 1.776 |

| H | 1.187 | 1.190 | 1.158 | 1.234 | 0.021 | 1.784 | ||

| K | 1.178 | 1.178 | 1.149 | 1.210 | 0.018 | 1.544 | ||

| L | 1.176 | 1.175 | 1.137 | 1.209 | 0.025 | 2.100 | ||

| PT | G | 1.143 | 1.146 | 1.104 | 1.179 | 0.020 | 1.737 | |

| H | 1.147 | 1.148 | 1.129 | 1.168 | 0.013 | 1.131 | ||

| K | 1.154 | 1.155 | 1.128 | 1.171 | 0.013 | 1.107 | ||

| L | 1.152 | 1.150 | 1.135 | 1.172 | 0.013 | 1.092 | ||

| S | G | 1.149 | 1.152 | 1.122 | 1.166 | 0.013 | 1.154 | |

| H | 1.154 | 1.154 | 1.137 | 1.165 | 0.010 | 0.860 | ||

| K | 1.157 | 1.158 | 1.144 | 1.184 | 0.011 | 0.985 | ||

| L | 1.153 | 1.153 | 1.126 | 1.179 | 0.015 | 1.321 |

| Factor | Sum of Square | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | Femp; F-Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main factors | |||||

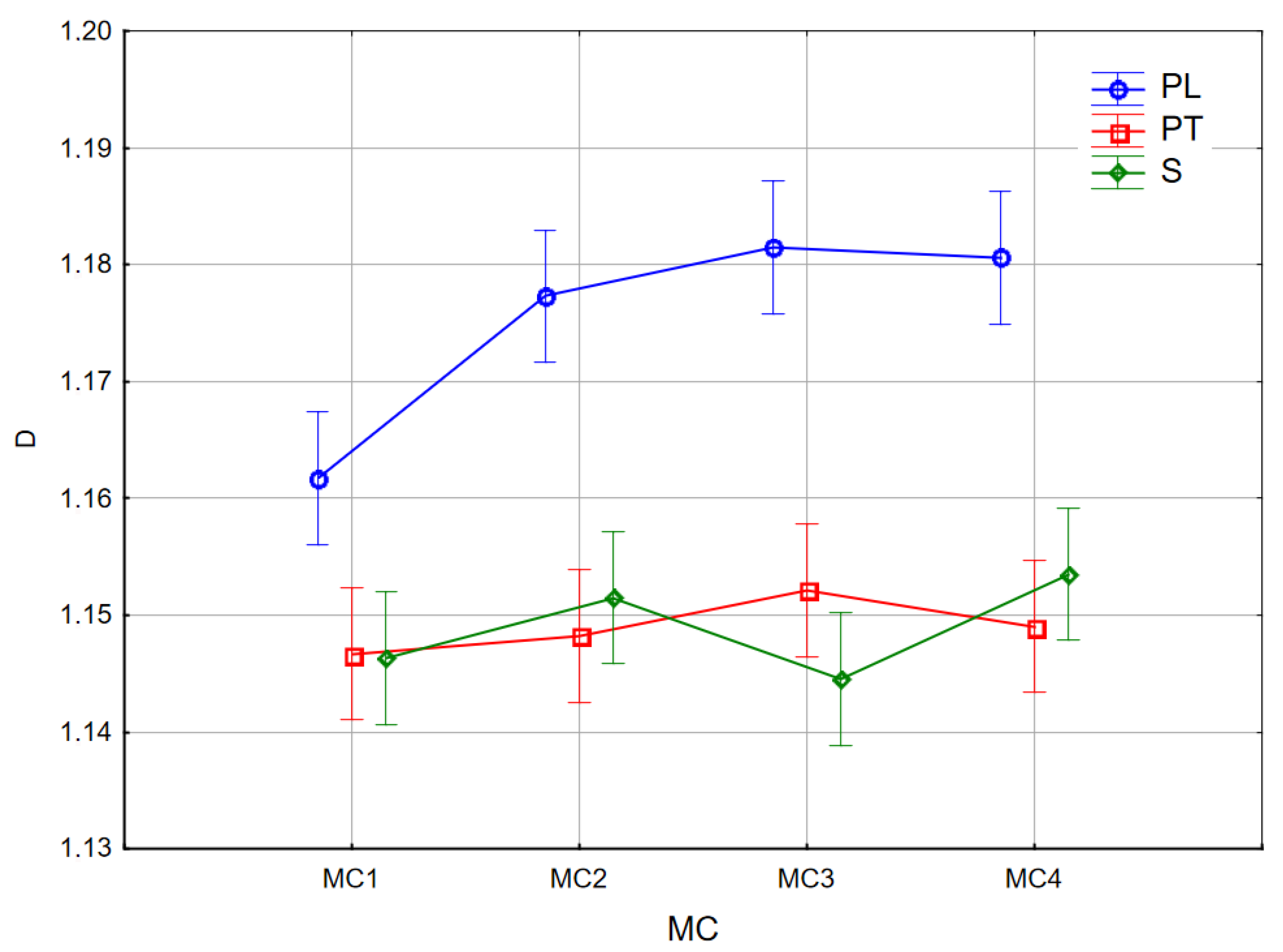

| MC: Moisture Content | 0.0064 | 3 | 0.0021 | 6 | 0.0003 |

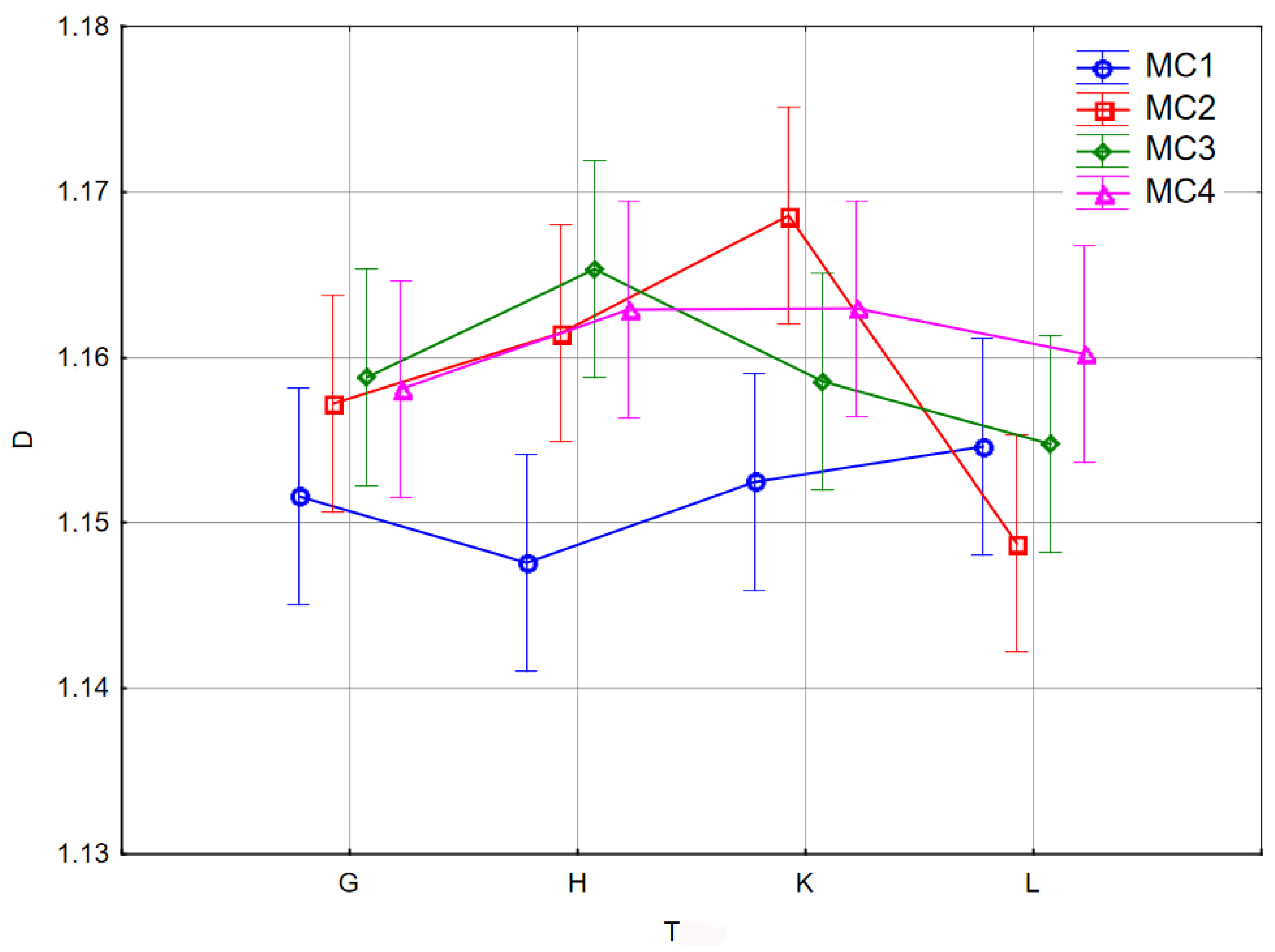

| T: Tree | 0.0027 | 3 | 0.0009 | 3 | 0.0440 |

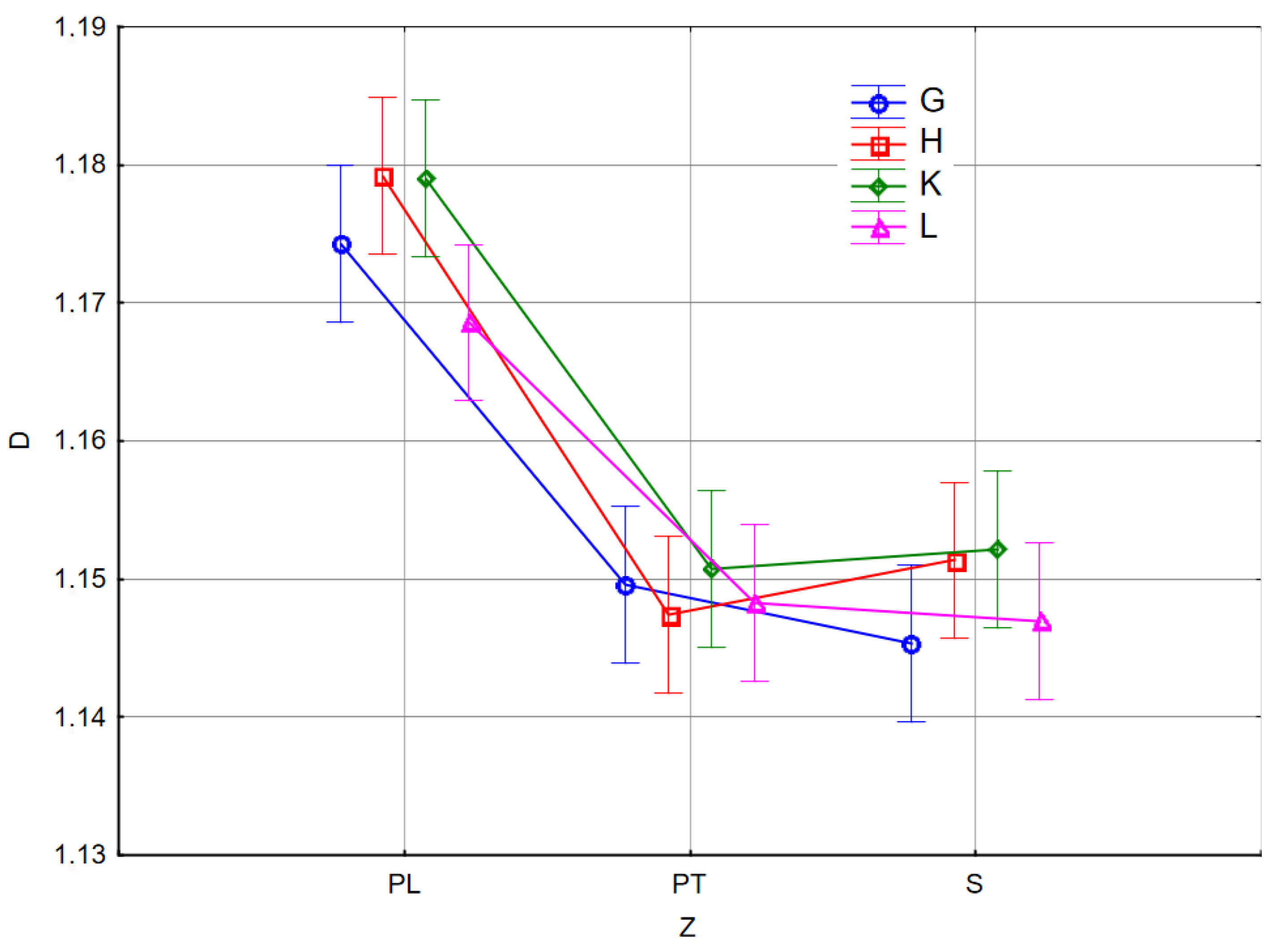

| Z: Cutting Unit | 0.0738 | 2 | 0.0369 | 111 | 0.0000 |

| Interactions | |||||

| MC × T | 0.0065 | 9 | 0.0007 | 2 | 0.0233 |

| MC × Z | 0.0066 | 6 | 0.0011 | 3 | 0.0035 |

| T × Z | 0.0019 | 6 | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.4651 |

| MC × T × Z | 0.0059 | 18 | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.4685 |

| Error | 0.1435 | 432 | 0.0003 | - | - |

| Moisture Content MC, % | Sample Size | Mean, % | Homogeneous Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Group II | |||

| 49.50 | 120 | 1.152 ± 0.021 | × | |

| 37.42 | 120 | 1.159 ± 0.023 | × | |

| 27.54 | 120 | 1.159 ± 0.024 | × | |

| 22.10 | 120 | 1.161 ± 0.022 | × | |

| Tree T | Sample Size | Mean, % | Homogeneous Groups | |

| Group I | Group II | |||

| L | 120 | 1.155 ± 0.019 | × | |

| G | 120 | 1.156 ± 0.024 | × | × |

| H | 120 | 1.159 ± 0.023 | × | × |

| K | 120 | 1.161 ± 0.024 | × | |

| Cutting Unit Z | Sample Size | Mean, % | Homogeneous Groups | |

| Group I | Group II | |||

| S | 160 | 1.149 ± 0.016 | × | |

| PT | 160 | 1.149 ± 0.017 | × | |

| PL | 160 | 1.175 ± 0.022 | × | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nowakowski, T.; Tucki, K.; Gruz, Ł. The Effect of Cutting Technique on the Degree of Damage to Fruit Tree Shoots. Agriculture 2026, 16, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010115

Nowakowski T, Tucki K, Gruz Ł. The Effect of Cutting Technique on the Degree of Damage to Fruit Tree Shoots. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowakowski, Tomasz, Karol Tucki, and Łukasz Gruz. 2026. "The Effect of Cutting Technique on the Degree of Damage to Fruit Tree Shoots" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010115

APA StyleNowakowski, T., Tucki, K., & Gruz, Ł. (2026). The Effect of Cutting Technique on the Degree of Damage to Fruit Tree Shoots. Agriculture, 16(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010115