Sensitivity Analysis of N2O and CH4 Emissions in a Winter Wheat–Rice Double Cropping System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. The SPACSYS Model

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis Design

2.3.1. Weather Conditions

2.3.2. Soil Property Settings

2.3.3. Fertilization Practices

2.3.4. Model Required Parameters on Water, C and N Processes

2.4. The Sobol’s First-Order Method for Sensitivity Diagnostics

3. Results

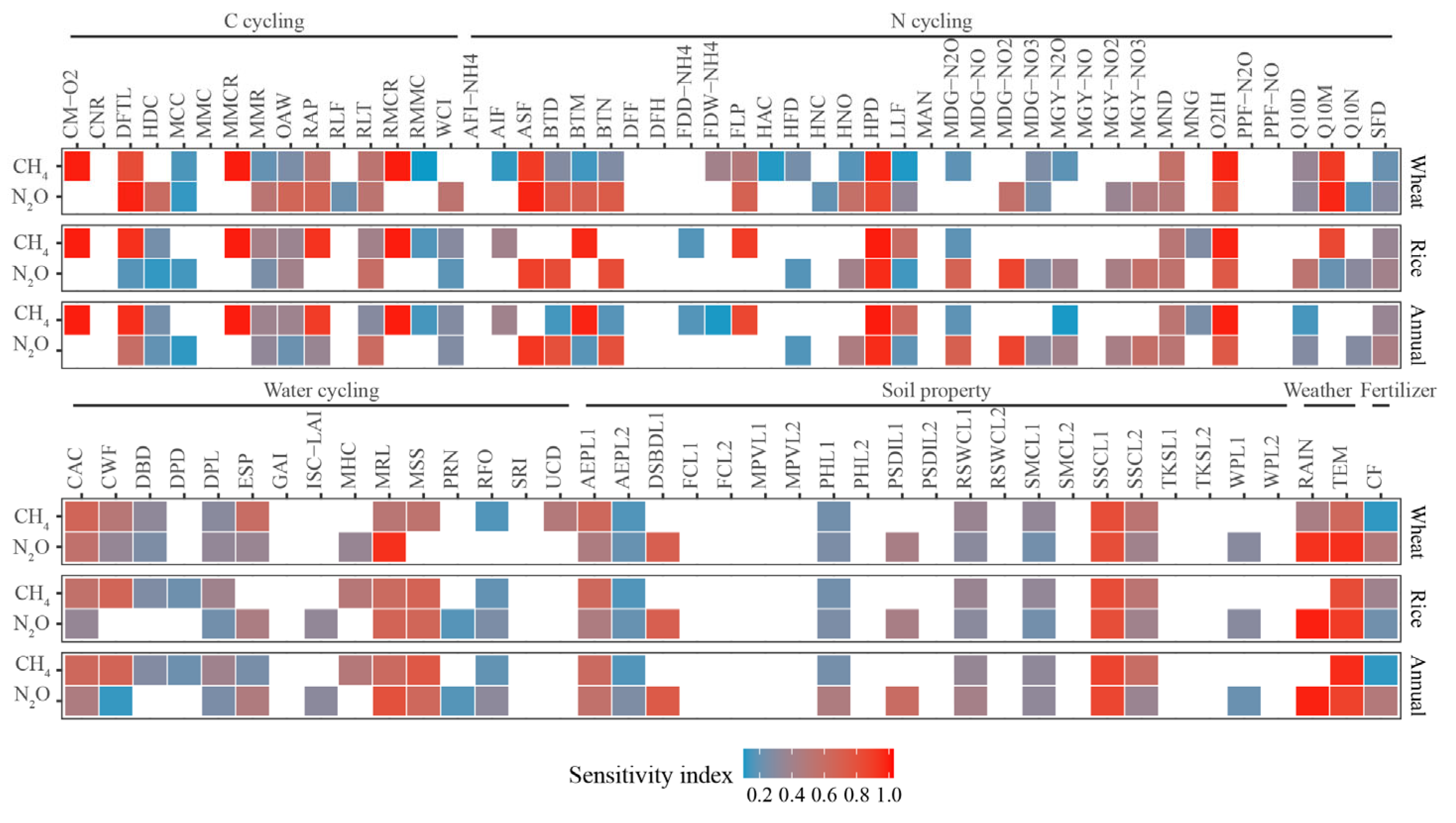

3.1. Fertilisation and Weather Impacts on N2O and CH4 Emissions

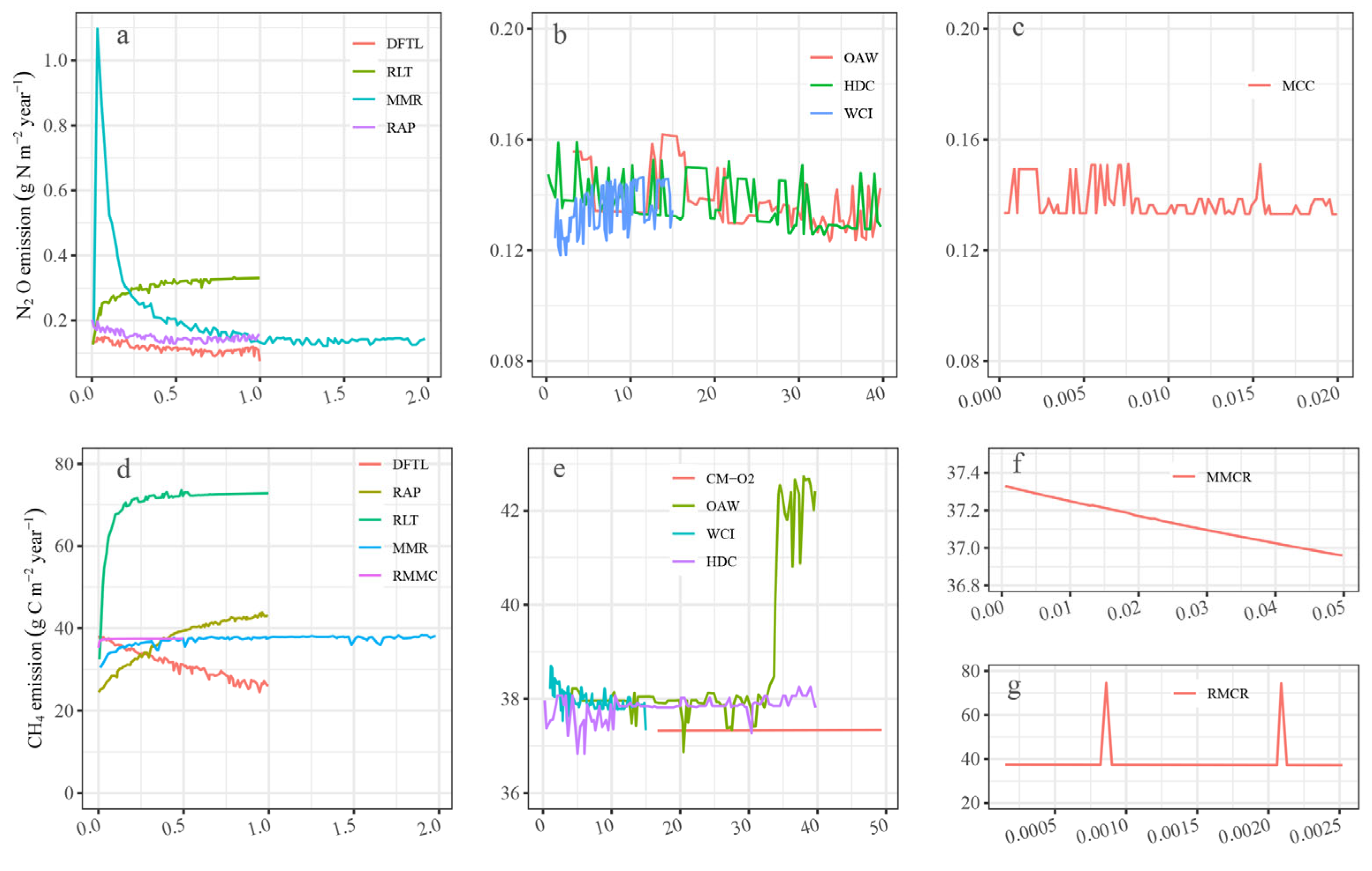

3.2. Relationships Between Simulated N2O and CH4 Emissions and Model Processes Parameters

3.2.1. Parameters in Soil Nitrogen Cycling

3.2.2. Parameters in Soil Carbon Cycling

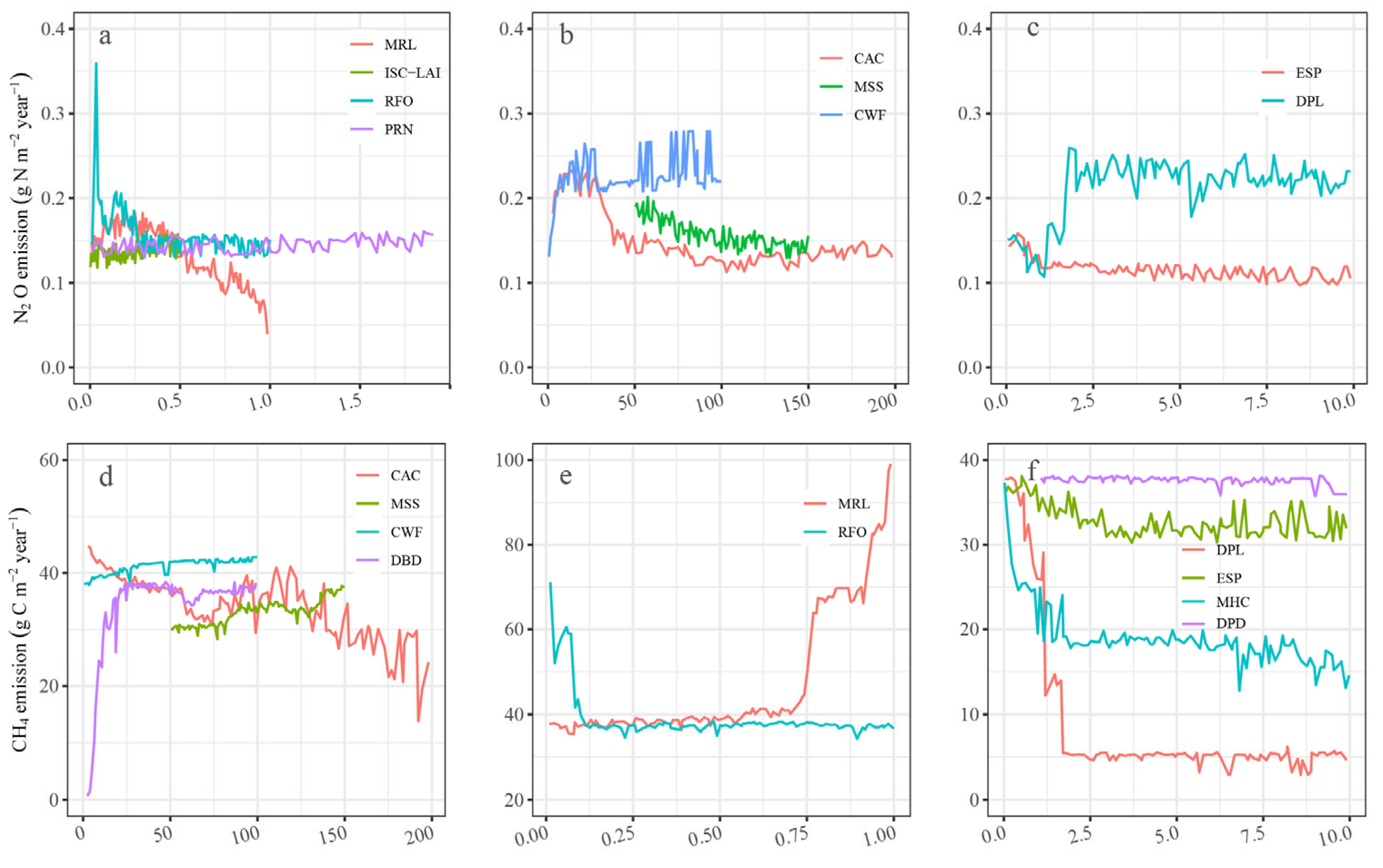

3.2.3. Water Cycling

3.3. Soil Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Previous Study

4.2. Effects of Fertilisation, Weather, Soil and Model Process Parameters on N2O and CH4 Emissions

4.3. Implications and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, G.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Song, K.; Dong, Y.; Lv, S.; Xu, H. Achieving low methane and nitrous oxide emissions with high economic incomes in a rice-based cropping system. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 259, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P.; Zhang, L.; Hurynovich, V.; He, Y. Greenhouse gases emissions and global climate change: Examining the influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waha, K.; Dietrich, J.P.; Portmann, F.T.; Siebert, S.; Thornton, P.K.; Bondeau, A.; Herrero, M. Multiple cropping systems of the world and the potential for increasing cropping intensity. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 64, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Liao, P.; Xu, Q. Effect of agricultural management practices on rice yield and greenhouse gas emissions in the rice–wheat rotation system in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, J. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from a Chinese wheat–rice cropping system under different tillage practices during the wheat-growing season. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 146, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Q.; Lin, W.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Yang, B.; Ding, R.; Shayakhmetoya, A.; et al. Driving soil N2O emissions under nitrogen application by soil environmental factor changes in garlic-maize rotation systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Thomson, P.; Clayton, H.; Mctaggart, I.; Conen, F. Effects of temperature, water content and nitrogen fertilisation on emissions of nitrous oxide by soils. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 3301–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz, A.; Linder, E.; Frolking, S.; Crill, P.; Keller, M. N2O emissions from humid tropical agricultural soils: Effects of soil moisture, texture and nitrogen availability. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Wu, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Gregorich, E. Effects of plant-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) on soil CO2 and N2O emissions and soil carbon and nitrogen sequestrations. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 96, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, T.; Xue, L.; Hou, P.; Xue, L.; Yang, L. Effects of warming and fertilization on paddy N2O emissions and ammonia volatilization. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 347, 108361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilova, O.V.; Suzina, N.E.; Van De Kamp, J.; Svenning, M.M.; Bodrossy, L.; Dedysh, S.N. A new cell morphotype among methane oxidizers: A spiral-shaped obligately microaerophilic methanotroph from northern low-oxygen environments. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2734–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokolo, N.L.; Enebe, M.C. Methane production and oxidation—A review on the pmoA and mcrA genes abundance for understanding the functional potentials of the agricultural soil. Pedosphere 2025, 35, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios, A.D.; Brar, S.K.; Ramírez, A.A.; Godbout, S.; Sandoval-Salas, F.; Palacios, J.H. Challenges in the measurement of emissions of nitrous oxide and methane from livestock sector. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, A.; Pérez-Batallón, P.; Macías, F. Responses of soil organic matter and greenhouse gas fluxes to soil management and land use changes in a humid temperate region of southern Europe. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Papen, H.; Rennenberg, H. Impact of gas transport through rice cultivars on methane emission from rice paddy fields. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, F.; Sun, X.; Geibel, M.C.; Prytherch, J.; Brüchert, V.; Bonaglia, S.; Broman, E.; Nascimento, F.; Norkko, A.; Humborg, C. High spatiotemporal variability of methane concentrations challenges estimates of emissions across vegetated coastal ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4308–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, B.; Martre, P. Plant and crop simulation models: Powerful tools to link physiology, genetics, and phenomics. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2339–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. SPACSYS (v6.00)—Installation and Operation Manual; Rothamsted Research: North Wyke, UK, 2019; Available online: http://www.rothamsted.ac.uk (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Wu, L.; Wu, L.; Bingham, I.J.; Misselbrook, T.H. Projected climate effects on soil workability and trafficability determine the feasibility of converting permanent grassland to arable land. Agric. Syst. 2022, 203, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, I.J.; Wu, L. Simulation of wheat growth using the 3D root architecture model SPACSYS: Validation and sensitivity analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 34, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Sun, N.; Wang, B.; Wu, L. Greenhouse gas emissions and stocks of soil carbon and nitrogen from a 20-year fertilised wheat-maize intercropping system: A model approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 167, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Le Cocq, K.; Chang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L. Climate change and environmental impacts on and adaptation strategies for production in wheat-rice rotations in southern China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 292–293, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonge, K.C.; Ascough, J.C.; Ahmadi, M.; Andales, A.A.; Arabi, M. Global sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of a dynamic agroecosystem model under different irrigation treatments. Ecol. Model. 2012, 231, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Sun, C. Time series global sensitivity analysis of genetic parameters of CERES-maize model under water stresses at different growth stages. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 275, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianosi, F.; Beven, K.; Freer, J.; Hall, J.W.; Rougier, J.; Stephenson, D.B.; Wagener, T. Sensitivity analysis of environmental models: A systematic review with practical workflow. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 79, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Ratto, M.; Andres, T.; Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Gatelli, D.; Saisana, M.; Tarantola, S. Introduction to Sensitivity Analysis, Global Sensitivity Analysis. The Primer; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanuytrecht, E.; Raes, D.; Willems, P. Global sensitivity analysis of yield output from the water productivity model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 51, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Huang, M.; Harris, P.; Wu, L. A Sensitivity Analysis of the SPACSYS Model. Agriculture 2021, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Yuan, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L. Optimizing fertilization strategies for a climate-resilient rice–wheat double cropping system. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2024, 129, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRB IUSS Working Group. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015 International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Reports 2015, No. 106; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; McGechan, M.; McRoberts, N.; Baddeley, J.; Watson, C. SPACSYS: Integration of a 3D root architecture component to carbon, nitrogen and water cycling—Model description. Ecol. Model. 2007, 200, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrekov, A.F.; Glagolev, M.V.; Alekseychik, P.K.; Smolentsev, B.A.; Terentieva, I.E.; Krivenok, L.A.; Maksyutov, S.S. A process-based model of methane consumption by upland soils. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raivonen, M.; Smolander, S.; Backman, L.; Susiluoto, J.; Aalto, T.; Markkanen, T.; Mäkelä, J.; Rinne, J.; Peltola, O.; Aurela, M.; et al. HIMMELI v1.0: HelsinkI Model of MEthane buiLd-up and emIssion for peatlands. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 4665–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susiluoto, J.; Raivonen, M.; Backman, L.; Laine, M.; Makela, J.; Peltola, O.; Vesala, T.; Aalto, T. Calibrating the sqHIMMELI v1.0 wetland methane emission model with hierarchical modeling and adaptive MCMC. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 1199–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Comput. Simul. 2001, 55, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.D. Factorial Sampling Plans for Preliminary Computational Experiments. Technometrics 1991, 33, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griensven, A.; Meixner, T.; Grunwald, S.; Bishop, T.; Diluzio, M.; Srinivasan, R. A global sensitivity analysis tool for the parameters of multi-variable catchment models. J. Hydrol. 2006, 324, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, K.S.; Cantarella, H.; Soares, J.R.; Gonzaga, L.C.; Menegale, P.L.d.C. DMPP mitigates N2O emissions from nitrogen fertilizer applied with concentrated and standard vinasse. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; He, K.-H.; Lin, K.-T.; Fan, C.; Chang, C.-T. Addressing nitrogenous gases from croplands toward low-emission agriculture. npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 2022, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénault, C.; Grossel, A.; Mary, B.; Roussel, M.; Léonard, J. Nitrous Oxide Emission by Agricultural Soils: A Review of Spatial and Temporal Variability for Mitigation. Pedosphere 2012, 22, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; Miguez, F.E.; Kaspar, T.C.; Castellano, M.J. Do cover crops increase or decrease nitrous oxide emissions? A meta-analysis. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 69, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eash, L.; Ogle, S.; McClelland, S.C.; Fonte, S.J.; Schipanski, M.E. Climate mitigation potential of cover crops in the United States is regionally concentrated and lower than previous estimates. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautakoski, H.; Korkiakoski, M.; Mäkelä, J.; Koskinen, M.; Minkkinen, K.; Aurela, M.; Ojanen, P.; Lohila, A. Exploring temporal and spatial variation of nitrous oxide flux using several years of peatland forest automatic chamber data. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 1867–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrage, N.; Velthof, G.L.; van Beusichem, M.L.; Oenema, O. Role of nitrifier denitrification in the production of nitrous oxide. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorts, K.; Merckx, R.; Gréhan, E.; Labreuche, J.; Nicolardot, B. Determinants of annual fluxes of CO2 and N2O in long-term no-tillage and conventional tillage systems in northern France. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 95, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grados, D.; Kraus, D.; Haas, E.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Olesen, J.E.; Abalos, D. Common agronomic adaptation strategies to climate change may increase soil greenhouse gas emission in Northern Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 349, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimsch, L.; Vira, J.; Fer, I.; Vekuri, H.; Tuovinen, J.-P.; Lohila, A.; Liski, J.; Kulmala, L. Impact of weather and management practices on greenhouse gas flux dynamics on an agricultural grassland in Southern Finland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, R. Microbial Ecology of Methanogens and Methanotrophs. Adv. Agron. 2007, 96, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlings, D.W.; Grace, P.R.; Kiese, R.; Weier, K.L. Environmental factors controlling temporal and spatial variability in the soil-atmosphere exchange of CO2, CH4 and N2O from an Australian subtropical rainforest. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 18, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Redfern, S.A.T. Impact of interannual and multidecadal trends on methane-climate feedbacks and sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Jia, Z.; Tian, L.; Wang, S.; Chang, C.; Ji, L.; Chang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tian, C. Potential functional differentiation from microbial perspective under dryland-paddy conversion in black soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 353, 108562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tu, S.; Lindström, K. Soil microbial biomass, crop yields, and bacterial community structure as affected by long-term fertilizer treatments under wheat-rice cropping. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daron, J.D.; Sutherland, K.; Jack, C.; Hewitson, B.C. The role of regional climate projections in managing complex socio-ecological systems. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Morais, M.C.; Pereira, S.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Santos, M. Tree–Crop Ecological and Physiological Interactions Within Climate Change Contexts: A Mini-Review. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 661978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth | Clay | Silt | Sand | BD | pH | SOM | TN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (g cm−3) | (g kg−1) | (g kg−1) | |

| 0–20 | 20.8 | 63.4 | 15.8 | 1.19 | 6.0 | 14.8 | 1.07 |

| 20–40 | 18.1 | 63.5 | 18.4 | 1.53 | 6.4 | 10.6 | – |

| 40–60 | 17.9 | 54.6 | 27.5 | 1.53 | 6.4 | 6.2 | – |

| Description | 0–10 cm | 10–20 cm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviation | Value | Abbreviation | Value | |

| pH value (-) | PHL1 | 6.36 | PHL2 | 6.4 |

| Air entry pressure (cm water) | AEPL1 | 46.8 | AEPL2 | 46.2 |

| Pore size distribution index (-) | PSDIL1 | 0.31 | PSDIL2 | 0.35 |

| Macro pore volume (vol%) | MPVL1 | 4 | MPVL2 | 6.3 |

| Saturated total conductivity (mm day−1) | TKSL1 | 743 | TKSL2 | 1060 |

| Saturated matrix conductivity (mm day−1) | SMCL1 | 22.4 | SMCL2 | 22.4 |

| Water content at wilting point (vol%) | WPL1 | 13.3 | WPL2 | 7.9 |

| Field capacity (vol%) | FCL1 | 27.2 | FCL2 | 22.5 |

| Saturated water content (vol%) | SSCL1 | 45.4 | SSCL2 | 39.5 |

| Residue water content (vol%) | RSWCL1 | 6.8 | RSWCL2 | 4.1 |

| Dry soil bulk density (g cm−3) | DSBDL1 | 1.19 | DSBDL2 | 1.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L. Sensitivity Analysis of N2O and CH4 Emissions in a Winter Wheat–Rice Double Cropping System. Agriculture 2026, 16, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010011

Liu C, Wang J, Sun Z, Sun Y, Liu Y, Wu L. Sensitivity Analysis of N2O and CH4 Emissions in a Winter Wheat–Rice Double Cropping System. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chuang, Jiabao Wang, Zhili Sun, Yixiang Sun, Yi Liu, and Lianhai Wu. 2026. "Sensitivity Analysis of N2O and CH4 Emissions in a Winter Wheat–Rice Double Cropping System" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010011

APA StyleLiu, C., Wang, J., Sun, Z., Sun, Y., Liu, Y., & Wu, L. (2026). Sensitivity Analysis of N2O and CH4 Emissions in a Winter Wheat–Rice Double Cropping System. Agriculture, 16(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010011