1. Introduction

Despite the recent boom in agricultural exports, advances in productive modernisation, and renewed gains in diversification and efficiency, Peru’s agricultural sector continues to face a form of structural vulnerability shaped by external forces. Among these, movements in the terms of trade (hereafter TOT) stand out, as fluctuations in relative international prices can influence both the trajectory and the structural sustainability of agricultural growth. In theoretical terms, the TOT are key determinants of the macroeconomic cycle, and in a country such as Peru—where mining accounts for nearly 60% of total export value [

1]—swings in global prices not only affect the trade balance and fiscal revenues, but also reshape the macroeconomic environment in which agriculture operates. This sector provides around 30% of national employment—mostly rural [

2]—and plays a strategic role in food security, poverty reduction and territorial cohesion [

3].

In recent years, globalisation, technological expansion and rising environmental requirements have transformed agriculture profoundly, situating it at the centre of economic, social and ecological debates [

4,

5]. Yet academic attention in Peru has tended to prioritise the mining sector, largely because of its influence on the exchange rate and the current account [

6], leaving the agricultural dimension of structural sustainability comparatively understudied. This omission is not trivial: agriculture combines social, productive and commercial functions, acting both as a generator of livelihoods and as a stabilising sector [

7,

8]. Understanding the factors that shape its growth dynamics is therefore essential.

Peru’s agricultural sector has shown sustained dynamism, both domestically and internationally. In real terms (base 2007 = 100), agricultural output rose from 11.15 billion soles in 1994 to 33.35 billion in 2024, averaging annual growth of 4.1% [

9]. Although its share of national GDP has hovered between 5.7% and 7% in recent years, family agriculture represents 97% of all productive units [

9,

10], underscoring its social embeddedness and territorial importance. This heterogeneous structure—anchored in crop diversification (coffee, blueberries, grapes, asparagus [

11]) and the continued expansion of agro-exports—not only generates income and employment but also strengthens economic resilience [

12], particularly in a context marked by external vulnerability.

Even so, the sector’s performance is far from autonomous. The TOT—defined as the ratio between export and import price indices—affect agriculture through multiple channels [

8]. International prices determine export revenues, while imported inputs such as fertilisers, machinery and fuels shape production costs [

13]. When the TOT improve, export earnings may rise but the domestic currency may appreciate and imported inputs become more expensive. When the TOT deteriorate, foreign currency becomes scarce, restricting both public and private investment. In this sense, TOT dynamics constitute a multifaceted transmission mechanism that can either reinforce or constrain agricultural sustainability, depending on the phase of the external cycle.

In other regions—particularly in parts of Africa and Central America—where agriculture is the main source of foreign exchange, its connection with the TOT is direct and highly visible. In Peru, by contrast, agriculture does not lead the trade balance; however, its expansion in recent decades positions it as a strategic sector capable of attenuating the risks associated with mining concentration [

14]. This intermediate position raises concerns about the extent to which agriculture can consolidate itself as a pillar of structural sustainability within a resource-dependent economy such as Peru.

The concern is hardly new. More than half a century ago, Prebisch and Singer warned of the long-term decline in the relative prices of agricultural goods vis-à-vis manufactures—a pattern that forced countries to export more merely to import the same amount [

15]. Although Peru does not fit this pattern neatly, given that its foreign exchange earnings come predominantly from mining, the rise of agricultural exports opens a similar scenario: an emerging sector that is gaining economic importance while remaining exposed to the fluctuations of international prices. Understanding this relationship is essential to assess whether agriculture can stabilise economic growth or whether it remains conditioned by external cycles.

Over recent decades, the re-primarisation of Peru’s productive structure has reinforced its sensitivity to commodity price shocks. This context justifies examining whether a long-run equilibrium relationship exists between the TOT and agricultural GDP, as well as the speed with which the sector corrects deviations following external disturbances [

16,

17]. This dynamic naturally points towards a cointegration-based approach, since only a long-run framework can reveal whether agriculture adjusts to external shocks or maintains its own structural path. Analysing this dynamic makes it possible to evaluate the degree of structural autonomy that agriculture has developed, providing an empirical foundation for assessing its sustainability over time.

The existing literature reveals a clear gap. Most studies on the impact of the TOT on economic growth—both in Peru and internationally—focus on aggregate effects [

18,

19], while sector-specific analyses remain scarce. Agricultural research typically prioritises themes such as productivity, innovation or water resources rather than examining the direct influence of external TOT, and when agricultural TOT are considered, the focus tends to be on national GDP rather than the agricultural product itself. Yet agricultural TOT are driven by sectoral price dynamics, whereas external TOT reflect global export–import movements [

20]. The transmission mechanisms into agriculture therefore differ, operating through foreign exchange flows, the real exchange rate and the cost of imported inputs [

21,

22].

This study seeks to fill that analytical gap. It examines whether external TOT sustain a long-run equilibrium relationship with Peru’s agricultural GDP and whether the sector responds to international price shocks as a dependent or resilient sector. This approach links the literature on external vulnerability with a sectoral perspective that has been largely overlooked, offering a novel contribution to academic debate and to policy discussions on sustainable development.

From the standpoint of open-economy theory, TOT may influence agriculture through fiscal, monetary and demand channels [

23]. A favourable external cycle increases public revenues and rural infrastructure investment, supports macroeconomic stability and encourages private investment; by stimulating activity in other sectors, it also raises domestic food demand. Conversely, prolonged TOT deterioration weakens these mechanisms and undermines the sector’s capacity for autonomous growth [

23,

24,

25]. Although the present study does not model these channels explicitly, it assumes that, if cointegration exists, the transmission effects will be embedded implicitly within the joint dynamics of the series.

In summary, the aim of the research is to determine whether the TOT sustain a long-run relationship with Peru’s agricultural GDP and to assess the implications of this linkage for structural sustainability. To that end, the study applies Johansen cointegration techniques and a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM), which enable the identification of common trends and the estimation of adjustment speeds following external shocks. Confirming such a relationship would indicate that the sector’s trajectory is shaped not only by its internal dynamics but also by global forces that condition its sustainability. Beyond the Peruvian case, the results may serve as a reference for other emerging economies that face similar challenges of primary dependence and seek to strengthen agriculture as a pillar of structural sustainability within an increasingly volatile global environment.

More broadly, the study carries international relevance because it addresses a challenge common to many countries with productive structures similar to that of Peru—resource-dependent economies with expanding but externally vulnerable agricultural sectors. The empirical evidence offered here may be useful for multilateral organisations, development agencies and policymakers seeking strategies for resilient rural development and structural sustainability. Finally, the findings directly relate to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, notably SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), by providing an analytical basis that connects macroeconomic equilibria with agricultural stability and national welfare.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The

Section 1.1 presents the literature review and the theoretical framework that guide the analysis.

Section 2 outlines the data, materials and econometric methods.

Section 3 reports the main empirical results, while

Section 4 offers the discussion, including policy considerations and directions for future research. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusions of the study.

1.1. Literature Review

In line with the discussion set out in the introduction, empirical evidence directly linking the TOT to agricultural GDP remains limited; nevertheless, the available literature provides a useful foundation for approaching this relationship. Although much of the existing research focuses on aggregate dynamics or on broad baskets of commodities, these works offer conceptual and methodological insights into how external shocks are transmitted to specific sectors. In this sense, the literature does not replicate the precise approach adopted here, but it helps to frame the transmission channels, heterogeneity of responses and adjustment mechanisms that also shape agricultural performance.

Recent contributions have refined the link between the TOT and economic activity by emphasising not only levels but also volatility and composition. At the aggregate level, the TOT are associated with growth, although the sign and magnitude of the effect vary according to each economy’s productive structure and exposure to external prices—hence the need to avoid universal generalisations and to recognise cross-country heterogeneity [

16]. Complementing this view, evidence from commodity-specialised countries shows that volatility in commodity TOT (CTOT) tends to weaken sectoral growth, with financial constraints amplifying losses [

26], while certain trade policy announcements (e.g., export restrictions) heighten agricultural price volatility and add an additional layer of regulatory uncertainty [

27].

A parallel line of research disaggregates the TOT into baskets (food, energy, manufactures) to capture heterogeneous effects. Studies indicate that commodity prices possess predictive capacity for future growth, but the direction and strength of the signal depend on each country’s specific exposure [

28,

29]. Shahzad’s work for the United States, for example, finds positive associations for ‘goods TOT’ and ‘computers and communications TOT’, and negative ones for ‘fuel TOT’ and ‘food TOT’, illustrating how composition may alter the net effect [

30]. This implication is highly relevant for small open economies in which TOT are shaped by metals while agriculture is intensive in imported fertilisers and energy: the effect on agricultural GDP will ultimately reflect the balance between income and cost channels.

Within the agricultural sphere, the recent literature highlights the importance of imported inputs as a transmission mechanism. The fertiliser market disruption of 2021–2022 increased global production costs and placed pressure on land use and yields [

31]. Evidence of persistent tensions in fertiliser markets supports the centrality of the input channel when assessing agriculture’s exposure to external shocks [

32]. Geopolitical conflict—most notably the Russia–Ukraine war—has further intensified fertiliser price volatility and disrupted supply chains, with small open economies such as Peru absorbing part of this disturbance through the TOT, which embed global price shifts into a single relative-price indicator [

33,

34]. More broadly, the food, fuel and fertiliser crisis initiated in 2020 continues to affect international markets [

31]. These shocks have hit smallholders particularly hard, especially in low- and middle-income countries [

31,

35], underscoring the need for adaptive strategies and mitigation policies that address volatility in input and supply prices [

36,

37].

For the Peruvian case, the evidence is notably scarce. A single empirical study finds a positive and statistically significant long-run association, estimating that a 1% improvement in the TOT is linked to a 0.26% increase in agricultural GDP, interpreted through income, cost and fiscal-investment channels [

8]. Although informative, the analysis relies on only twenty-three annual observations and an OLS specification without unit-root or adjustment tests, limiting its ability to identify long-run equilibrium behaviour. Even so, it provides a useful point of departure and underscores the relevance of assessing the TOT–agriculture nexus within a framework capable of capturing long-run comovement and the speed of correction.

Beyond these sector-specific contributions, methodological advances based on cointegration and error-correction models have enhanced the ability to examine long-run sectoral relationships. Applications in agricultural markets show that prices and quantities often move towards a long-run equilibrium and that deviations tend to be corrected at a measurable speed. A study for Turkey (2002–2021), for example, identifies both short- and long-run relationships in agricultural prices and reports a negative and significant correction term, signalling gradual reversion to equilibrium after temporary disturbances [

38].

For emerging economies, additional evidence connects global commodity indices with growth. Studies on commodity-dependent countries and Eastern Europe detect long-run relationships between major price groups (food, energy, fertilisers, metals) and economic activity, emphasising that the export–import balance shapes the net sign of the impact [

39,

40]. Research for Latin America and the Caribbean also suggests that trade fragmentation and commodity-based specialisation condition the way external shocks are transmitted, depending on commercial architecture and regional integration [

41,

42].

Taken together, these strands of literature offer three insights that are directly relevant for a sectoral analysis of agriculture from a structural-sustainability perspective. First, the TOT–output relationship is heterogeneous: it varies with each country’s export–import composition and financial depth. Evidence from the United States, Pakistan, China, Australia and the United Arab Emirates shows that the sign and magnitude of TOT effects differ by sector, product group and trading partner [

30,

43,

44,

45]. At more disaggregated levels, complementarity between foreign investment and exports may appear at the country or industry level but weaken at the product level [

46], while firm-level findings show that financing conditions influence both export variety and value [

47]. For agriculture, this heterogeneity is essential, because the balance between imported-input dependence, export rents and credit conditions determines the net sign of TOT effects in each episode.

Second, uncertainty associated with prices and trade policies generates effects that are distinct from those driven by TOT levels. Evidence from the United States, Europe and multi-country studies shows that volatility and policy uncertainty can delay investment, reduce production and increase financing costs [

48,

49,

50,

51]. In the agricultural sector, uncertainty in the prices of imported inputs—fertilisers and energy—complicates planning and budgeting, even during favourable TOT cycles [

31,

35,

52].

Third, cointegration and error-correction approaches are particularly useful when long-run equilibrium and short-run dynamics coexist. Evidence from Algeria, Malawi, the Colombia–Venezuela trade relationship, Slovenia, and Turkey suggests that prices and quantities exhibit external anchoring with varying speeds of adjustment [

38,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. These findings support the use of a VECM to capture the interaction between external price cycles and sectoral output when homogeneous, continuous control-variable series are not available.

Overall, the reviewed literature highlights that the TOT can influence agricultural GDP through income, cost and financial-conditions channels, and that the strength of these links depends on exposure to imported inputs, export markets and macroeconomic volatility. This provides the conceptual basis for examining whether Peru’s agricultural GDP is anchored to external TOT in the long run and whether the sector’s adjustment dynamics are compatible with a trajectory of structural sustainability.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

In open economies, TOT—the price of exports relative to that of imports—operate as a relative or external “shadow price” shaping disposable income, input costs, and the allocation of factors across sectors [

58]. When TOT become more favourable, they expand the purchasing power of foreign currency and relax external constraints; when they deteriorate, they compress that space and make key imports more expensive [

59]. Beyond their level, the recent literature emphasises uncertainty: when TOT become more volatile, investment and economic activity tend to weaken due to rising macroeconomic and financial risk [

60]. To keep the interpretation clear, it is useful to view the TOT as a condensed signal that influences both external income and production costs, depending on the direction and intensity of each shock.

In this study, the economic significance of the TOT is interpreted in line with their dual role as both an income-generating and a cost-transmitting mechanism. Because the TOT summarise movements in external relative prices, they condense information about export revenue potential, exposure to imported inputs, and the pressure exerted on domestic factor allocation. A precise reading of the TOT therefore requires recognising that improvements may strengthen liquidity and external purchasing power, while deteriorations restrict foreign-currency availability and raise the operational costs of sectors that depend on imported fertilisers, fuels or machinery. This interpretation underpins the subsequent empirical analysis and clarifies why TOT dynamics constitute a meaningful source of long-run external anchoring for agriculture in a small open economy.

At the aggregate level, the TOT–GDP relationship can be organised into four channels: (i) an income effect, whereby improvements in TOT increase export revenues and public revenue, enabling higher public and private expenditure and investment; (ii) a cost effect, in which increases in import prices—energy, fertilisers, machinery—compress margins, reduce effective productivity and contract supply; (iii) the real exchange rate and reallocation channel, where TOT booms tend to appreciate the currency, raise the relative price of non-tradables and reallocate factors across sectors; when prolonged, this mechanism resembles Dutch disease dynamics; and (iv) financial conditions, as favourable TOT reduce risk premia, lower external financing costs and expand credit, reinforcing the cycle [

8,

16,

20,

24,

61]. Taken together, these channels allow a single TOT shock to generate different outcomes depending on each economy’s productive structure and financial depth.

From a sectoral perspective, TOT also affect agriculture, even when shocks do not originate within the sector. This occurs because TOT are transmitted through diverse channels [

24,

62,

63], simultaneously influencing (a) foreign currency earnings and thus the real exchange rate and domestic demand; (b) the cost of essential imported inputs—nitrogen fertilisers, diesel, agrochemicals, machinery; and (c) credit availability and public investment linked to the external cycle.

In this sense, the same mechanisms that explain the TOT–GDP link at the aggregate level can be extended to agriculture [

15,

16,

19,

43], given its dependence on imported inputs and international markets. The experience of 2021–2022 illustrates this point: the surge in international fertiliser prices sharply increased agricultural production costs and strained food security, even when export prices offered partial relief—showing that input shocks can dominate short-run dynamics [

31,

32].

Within this framework, the use of cointegration and error-correction models is justified because they separate long-run comovement from short-run adjustments without implying structural causality [

64,

65]. In this study, if the variables are cointegrated, the VECM provides the error-correction term, which reflects the speed of return to equilibrium: negative and significant coefficients indicate that deviations tend to be corrected gradually towards the long-run path [

66]. This methodological logic, applied in agricultural markets in Turkey, Algeria, Malawi and Slovenia, confirms that prices and quantities often show external anchoring, with heterogeneous adjustment rhythms [

38,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

Applied to agriculture, the above framework suggests three operational expectations. (i) If cointegration exists between TOT and agricultural GDP, it can be interpreted as a long-run equilibrium relationship with the international price cycle through aggregated income, cost and real exchange-rate channels [

24,

67], without the model attempting to disaggregate each transmission mechanism; (ii) the magnitude of the error-correction term in a VECM informs the sector’s absorption capacity in the face of external shocks [

67]: relatively rapid adjustments are compatible with resilience, whereas slower ones imply greater exposure, always in an aggregate sense; and (iii) short-run responses may be influenced by imported inputs (fertilisers, energy) or by export prices (rents and demand) [

35,

36], meaning that the balance between cost pressures and income gains will shape the net short-run effect in each episode.

In sum, this theoretical framework suggests that TOT affect agriculture through multiple channels, and that their interaction with agricultural GDP can be understood as a dynamic long-run equilibrium accompanied by transitory adjustments. However, this study does not explicitly model those channels—fiscal, cost-related, exchange rate or financial—due to the lack of homogeneous, continuous sectoral series that would allow the inclusion of control variables with sufficient representativeness. Instead, it assumes that, if cointegration exists, transmission effects are embedded implicitly in the joint dynamics of the variables. This preserves the internal coherence of the model while acknowledging that channel-specific identification remains a task for future research.

To provide conceptual clarity, this study operationalises structural sustainability as an empirical property emerging from the dynamic behaviour of the system. The notion is approximated through three complementary elements: (i) the existence of a long-run cointegrating relationship between agricultural GDP and the external terms of trade, interpreted as a stable external anchor; (ii) the sign and statistical significance of the error-correction coefficient in the agricultural equation, which reflects the sector’s capacity to absorb external shocks and return to its equilibrium path; and (iii) the magnitude of the adjustment parameter, understood as the speed with which deviations from equilibrium are corrected. Taken together, these components offer a quantitative approximation of structural sustainability within the context of a small open economy, providing an aggregate measure of the sector’s long-run stability under external price cycles.

Under this logic, it becomes necessary to empirically assess whether such anchoring exists in the Peruvian case and, in particular, whether the sector’s adjustment dynamics reveal a trajectory compatible with structural sustainability over time. The methodology section details the econometric approach adopted, the unit-root and cointegration tests applied, and the specification of the error-correction model that guides the analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

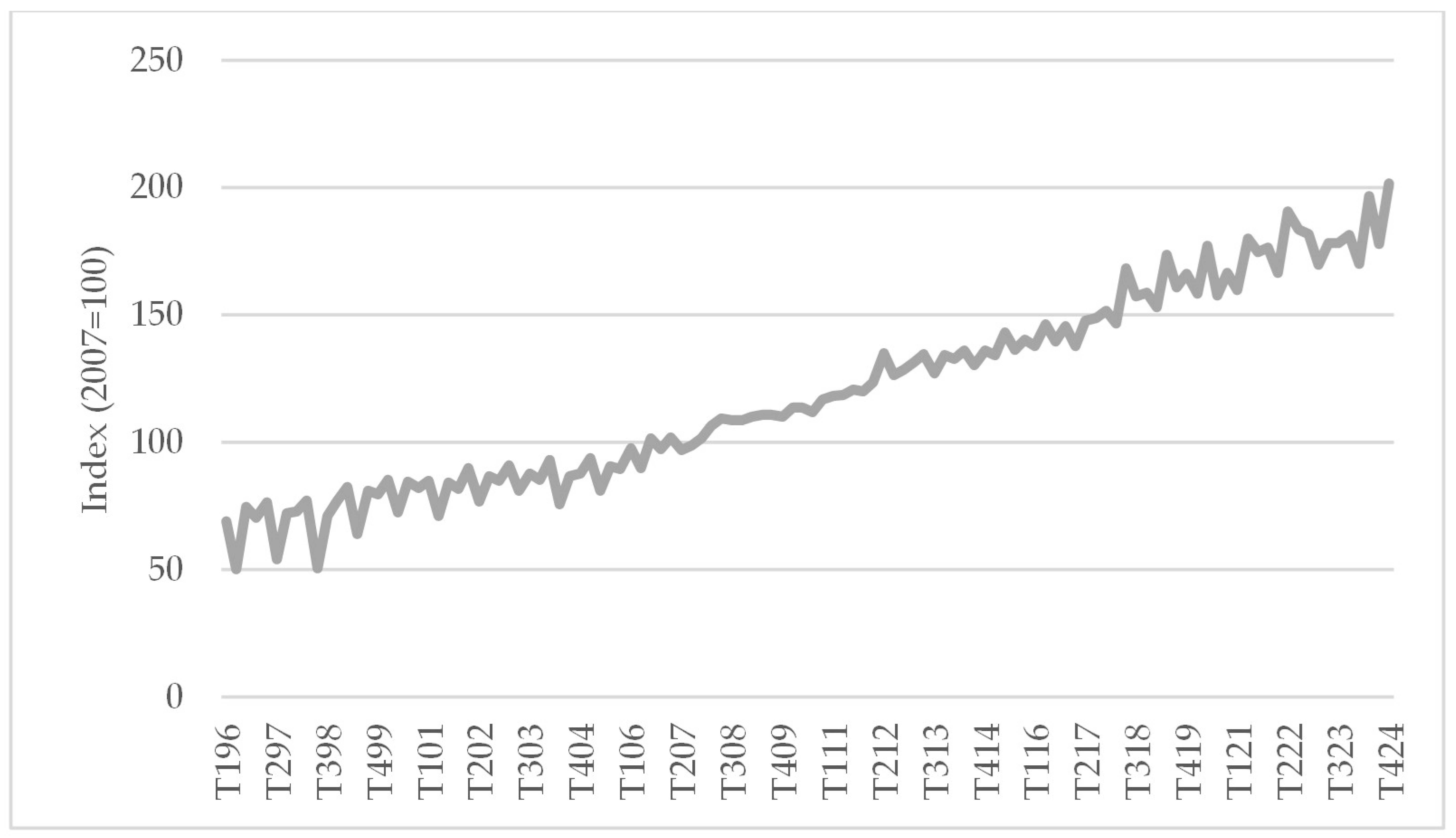

In line with the purpose of this study, the objective is to examine whether external TOT maintain a long-run equilibrium relationship with Peru’s agricultural GDP and to estimate the speed at which the sector corrects deviations following external shocks. This analysis is framed within the notion of structural sustainability, understood as the capacity of the agricultural sector to sustain a stable performance in the face of changing external conditions. To address this question, Johansen’s cointegration tests and a Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) are employed. The study adopts a quantitative, applied and ex post facto design, as it relies on previously observed information without any experimental manipulation. A total of 116 quarterly observations for each variable, covering the period 1996–2024, were used; all data were obtained from the database of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru (BCRP).

The original series are published as indices with base 2007 = 100, and the temporal coverage was selected to include the longest span of comparable data for both variables, ensuring that the estimation relies on the maximum availability of consistent observations and incorporates a sufficiently broad window to capture short- and long-run dynamics. The dependent variable corresponds to the real agricultural GDP, while the explanatory variable is the external TOT, defined as the ratio between the export price index and the import price index of the Peruvian economy, TOT = Px/Pm [

68]. In this context, agricultural GDP refers to the official quarterly index of real agricultural output compiled by the BCRP at constant prices (base year 2007 = 100). This series captures total value added in the agricultural sector and constitutes the dependent variable in the cointegration and VECM estimations. Agricultural GDP and TOT were transformed into logarithms to allow elasticities to be interpreted more naturally and to stabilise the variance.

Before estimating the model, agricultural GDP was seasonally adjusted using a multiplicative decomposition in Minitab 21 to address the marked seasonality inherent to agricultural activity. The transformation produces a series that reflects more clearly the underlying trend and structural behaviour of the sector.

The econometric strategy follows standard procedures for testing long-run relationships in macroeconomic time series. First, unit-root tests (ADF and KPSS) were applied to establish the order of integration of each variable. Lag selection for the system was then conducted using conventional information criteria, recognising that the VECM is a re-parametrisation of the VAR in levels. Johansen’s methodology was subsequently applied to test for the existence of at least one cointegrating vector, providing the basis for the long-run equilibrium analysis [

69,

70].

The dynamic behaviour of the system is represented through the error-correction formulation, which combines short-run adjustments with deviations from the long-run path. The general form of the VECM is expressed as follows:

where

∆ denotes the first difference;

is the natural logarithm of real agricultural GDP in period t;

represents the natural logarithm of TOT;

p is the optimal number of lags selected using information criteria;

βi and γj capture the short-run dynamics of agricultural GDP and TOT, respectively;

is the error-correction term obtained from the cointegrating vector;

λ measures the speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium;

α0 is the constant term;

εt is the random error term.

Under this methodological framework, three hypotheses were formulated concerning cointegration, the adjustment capacity of the agricultural sector and the exogenous behaviour of TOT, which guide the estimation and empirical testing of the model (see

Table 1).

The following section presents the empirical results, which assess the long-run relationship between the terms of trade (TOT) and agricultural GDP and the sector’s adjustment mechanism to external disturbances.

3. Results

3.1. Unit Root Tests and Lag Selection

To ensure the validity of the cointegration approach, the ADF and KPSS tests were applied to lnGDP

agr and lnTOT in levels and in first differences (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). Recall that in ADF the null hypothesis H

0 is “unit root”, whereas in KPSS the null hypothesis H

0 is “stationarity”. In the table, NR indicates “no rejection” of the corresponding null hypothesis and R indicates “rejection”. For lnGDP

agr, the ADF test in levels yields

p = 0.113 (NR), meaning that the unit-root null cannot be rejected; the KPSS test in levels reports a statistic of 0.1248 with

p ≈ 0.092 (R at the 10% level), thus rejecting the null of stationarity. In first differences, the ADF test yields

p = 0.000 (R), rejecting the unit-root null; KPSS shows 0.0198 with

p > 0.10 (NR), meaning that stationarity cannot be rejected. Taken together, lnGDP

agr is I(1): non-stationary in levels and stationary in differences.

For lnTOT, the ADF test in levels reports

p = 0.209 (NR), so the unit-root null cannot be rejected; the KPSS test in levels records 0.2369 with

p < 0.01 (R), thus rejecting the null of stationarity. In first differences, ADF yields

p = 0.000 (R), rejecting the unit-root null; KPSS shows 0.0530 with

p > 0.10 (NR), meaning that stationarity cannot be rejected. In sum, lnTOT is also I(1). As shown in

Table A1 (

Appendix A), the combined evidence from ADF and KPSS is consistent: both series are I(1). This enables the Johansen test and the estimation of the VECM, in which the dynamics are modelled in first differences while incorporating the error-correction term to capture the return to the long-run equilibrium.

Lag length was determined on the basis of the Akaike (AIC), Schwarz (BIC) and Hannan–Quinn (HQC) information criteria. As reported in

Table A2 (

Appendix A), the AIC favours five lags (

p = 5), while the BIC and HQC point to four (

p = 4). Given the nature of quarterly macroeconomic series—where cyclical dynamics and input-cost shocks may require a richer temporal structure—the model was estimated under both specifications. For the main analysis, the five-lag formulation was retained, as it offers a more complete representation of short-run adjustments and preserves the stability of the error-correction mechanism, while remaining consistent with standard applications in cointegration studies using long-horizon quarterly data.

3.2. Johansen Cointegration Test

Consistent with the criterion defined in the previous section, Johansen’s cointegration test was carried out using a single lag order (

p = 5). The test was implemented under the assumption of a restricted constant in the cointegration space, a recommended practice for I(1) series without a marked deterministic trend, as it incorporates a mean equilibrium level without introducing drift into the system; this specification supports a rigorous and parsimonious assessment of the long-run relationship. The results show that r = 0 is rejected (trace = 31.703,

p ≈ 0.0006; max-eigen = 23.778,

p ≈ 0.0016) and r ≤ 1 is not rejected (trace = 7.925,

p ≈ 0.0866; max-eigen = 7.925,

p ≈ 0.0866), indicating the presence of a single cointegrating vector (see

Table 2).

Given that the cointegration analysis provides clear evidence of r = 1, the next step: estimating an error-correction model (ECM) derived from the bivariate VECM, incorporating the correction term as a bridge between the long-run equilibrium and the short-run adjustments. This enables the precise assessment of whether agricultural GDP corrects deviations (speed and sign of the adjustment coefficient) and whether TOT behave as exogenous within the system, thereby completing the econometric strategy proposed in the study.

3.3. ECM Estimation via VECM

Verified the existence of cointegration between the variables, the error-correction model (ECM) was then estimated from the bivariate VECM system. This estimation makes it possible to combine short-run dynamics with the adjustment process towards the long-run equilibrium, capturing the speed at which agricultural GDP corrects deviations caused by variations in the TOT, while simultaneously revealing the behaviour of both series within a coherent and parsimonious econometric framework.

The ΔlnGDP

agr equation displays a solid autoregressive pattern consistent with the dynamics of the Peruvian agricultural sector. The coefficients of the first three lags of agricultural GDP remain negative and highly statistically significant (−0.61, −0.55 and −0.58;

p < 0.001), reflecting strong short-run inertia: when agricultural growth accelerates in one quarter, it tends to correct partially in the subsequent periods, revealing a regular cyclical pattern and an internal adjustment mechanism inherent to the sector (see

Table 3).

The fourth lag is positive and significant (0.254; p = 0.005), indicating a small compensatory rebound over slightly longer horizons. This is coherent with agricultural dynamics in which climatic or production shocks may generate initial corrections followed by moderate recoveries as the agricultural cycle progresses.

Regarding TOT, none of the four lags is significant. All display p-values well above 10 per cent, indicating the absence of statistically relevant short-run effects on agricultural growth. Although some coefficients show alternating signs, none consolidates as a persistent pattern, reinforcing the view that external shocks associated with TOT do not generate immediate or sustained responses in agricultural activity when a broader temporal memory is considered.

The error-correction coefficient (

λ) is negative and highly significant (−0.040;

p < 0.001), indicating that the agricultural sector corrects approximately 4 per cent of any deviation from the long-run equilibrium every quarter. Economically, this implies a gradual but persistent adjustment: shocks are absorbed slowly, consistent with seasonal cycles, input rigidities and investment lags that characterise Peruvian agriculture. At this pace, the implied half-life—computed as ln(0.5)/ln(1 − |

λ|)—is approximately seventeen quarters (just over four years), meaning that deviations dissipate only over extended horizons rather than quickly. This long adjustment window provides an initial indication of the sector’s structural behaviour and sets the stage for

Section 4, where its implications for resilience and policy will be examined.

The model’s information block indicates a very good level of fit (R2 = 0.880; adjusted R2 = 0.869) and a Durbin–Watson statistic of 1.89, close to the ideal value of 2. Taken together, the results confirm the robust internal dynamics of agricultural GDP, with a smooth yet firm correction path towards equilibrium, while the short-run effects of TOT remain virtually null and without appreciable persistence.

The equation modelling the short-run dynamics of TOT displays a stable behaviour that is practically decoupled from the agricultural cycle. The four lags of ΔlnGDP

agr show very small coefficients and

p-values well above 10 per cent, indicating that recent variations in agricultural GDP do not generate significant responses in TOT. This pattern reinforces the notion of weak exogeneity: TOT evolve autonomously with respect to the internal dynamics of the agricultural sector (see

Table 4).

In contrast, the first lag of TOT itself is positive and highly significant (0.371; p = 0.0004), revealing internal persistence: contemporaneous shocks to relative prices tend to extend for one quarter before dissipating. However, the second to fourth lags are not statistically relevant, so this persistence is brief and does not translate into a longer-memory process. The ECM is also not significant (p = 0.407), confirming that TOT do not adjust towards the long-run equilibrium. In other words, whereas agricultural GDP does correct structural deviations, TOT do not participate in that mechanism, consistent with their condition as an exogenous variable in a small and open economy such as Peru’s.

The model’s information block shows a modest fit (R2 = 0.156; adjusted R2 = 0.081), typical of structurally exogenous equations, and a Durbin–Watson statistic close to 2.00, suggesting the absence of relevant autocorrelation. Taken together, the evidence confirms that TOT behave as an external driving variable, with their own dynamics and without feedback from the agricultural sector.

Based on the results obtained, the three hypotheses set out in the methodology can be assessed clearly. First, the Johansen test rejects the null hypothesis of no cointegration and confirms the existence of a single long-run equilibrium vector between agricultural GDP and TOT, thereby confirming H1. Second, the error-correction term in the agricultural GDP equation is negative and highly significant, indicating that the sector corrects deviations from equilibrium with a stable and consistent speed; consequently, H2 is also confirmed. Finally, the coefficient of the error-correction term in the TOT equation is not significant, implying that TOT do not adjust in response to shocks originating in agricultural GDP; therefore, the null hypothesis is not rejected and H3 is validated, corroborating the weak exogeneity of the TOT within the system.

3.4. Robustness Checks

With the aim of verifying the robustness of the results, autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity and normality tests were carried out for both model specifications, together with a focused review of the potential incidence of the COVID-19 shock. In the autocorrelation contrast, there is only a marginal indication at the first order and no evidence at the remaining lags (see

Table A3 in

Appendix B). This pattern suggests that the model captures short-run serial dynamics effectively, and leads to coherent conclusions regarding cointegration, the adjustment of agricultural GDP, and the weak exogeneity of TOT.

Regarding heteroskedasticity, ARCH tests up to four orders reveal no signs of instability in the residual variance (see

Table A4 in

Appendix B). Although the Doornik–Hansen test rejects multivariate normality (see

Table A5 in

Appendix B), this does not compromise the validity of the estimates because the VECM is based on maximum-likelihood estimators that are consistent and asymptotically normal under standard regularity conditions [

71]. Hence, inference relies on the model’s asymptotic properties rather than on strict multivariate normality. Finally, the possibility of a break associated with COVID-19 was assessed. The deseasonalised agricultural GDP series shows no discontinuities in 2020, and institutional evidence indicates that the sector exhibited notable resilience [

72]. This resilience becomes clearer when examined against the broader context of 2020–2021. Peru’s inherent agricultural, livestock and fishing potential helped maintain food availability, while local producers and informal vendors adapted rapidly to mobility restrictions and compensated for bottlenecks in centralised supply chains [

73]. On the external front, agricultural exports grew by 6.7% in 2020, driven by non-traditional products such as mangoes, and avocado exports—where a 1% rise in shipments is associated with a 0.40% increase in GDP—provided an additional buffer during the crisis [

74,

75]. Informal food chains, supported by agrobiodiversity, sustained retailing, logistics and seed systems, reinforcing food security despite global disruptions [

76]. Nevertheless, global disruptions in logistics, labour availability and fertiliser markets during 2020–2021 did affect production conditions, influencing short-run dynamics [

77] even if they did not generate observable breaks in the series. For this reason, no intervention dummy was incorporated, a decision supported by

Figure A1,

Figure A2 and

Figure A3 in

Appendix C.

4. Discussion

The results confirm a long-run anchoring between the terms of trade (TOT) and agricultural GDP: Johansen identifies a single cointegrating vector, and the error-correction term in the agricultural equation is negative and highly significant, whereas in the TOT equation it is insignificant. In economic terms, Peru’s agricultural sector adjusts gradually towards an equilibrium conditioned by the external cycle, while the TOT do not respond to the sector’s internal dynamics—an outcome consistent with the nature of a small open economy and with the notion of weak exogeneity of external relative prices [

58,

61,

62]. The estimated speed of adjustment (≈4% per quarter) suggests resilience with frictions: the sector absorbs deviations, albeit over horizons shaped by seasonal patterns and the rigidity of key inputs. This interpretation is consistent with the empirical pattern observed in the model, where the ECM coefficient is the only statistically significant channel linking TOT to agricultural GDP in the short run, while all four ΔlnTOT lags remain insignificant, confirming that external shocks influence the sector primarily through long-run correction rather than through immediate quarterly transmission.

In practical terms, the evidence points to an agricultural sector that must navigate several quarters of adjustment each time international conditions turn unfavourable. Pressures stemming from fertiliser prices, energy costs or fluctuations in global freight do not disappear within a single campaign; instead, they stretch across seasons and weigh more heavily on producers operating with very narrow margins [

78,

79]. For family farmers and small-scale units, this pattern tends to materialise as more delicate planting windows, reduced ability to rebuild stocks of essential inputs and a gradual tightening of day-to-day liquidity [

80]. Export-oriented firms, whether medium-sized operators or large agribusinesses, also feel the implications: when movements in the TOT fail to fade within one cycle, planning unavoidably shifts towards longer horizons in order to smooth the accumulation of these disruptions across successive production rounds.

Viewed from this angle, the notion of structural sustainability hinges on two elements that the estimates reveal with clarity: the exogenous nature of the TOT and the slow pace at which deviations are corrected. Because agricultural GDP is the variable absorbing the adjustment—while the TOT remain largely indifferent to domestic dynamics—the sector remains tied to a global cycle it cannot influence. The adjustment unfolds only gradually, with a half-life that exceeds four years, leaving ample space for vulnerabilities to accumulate. When external shocks arrive before the effects of earlier disturbances have fully dissipated, the overlap can progressively erode the productive base that sustains agricultural growth.

Under this light, structural sustainability is challenged not by the absence of a long-run anchor—which the results do confirm—but by the temporal friction through which that anchor operates. The combination of external dependence and drawn-out corrections produces a landscape in which long-term stability is attainable, yet contingent on the presence of institutional and productive buffers capable of absorbing persistent shocks and preventing them from weakening rural productive capacity over time.

Beyond the statistical significance of the ECM, the magnitude of the adjustment carries its own economic relevance. A quarterly correction of roughly 4% implies a long half-life—on the order of sixteen to seventeen quarters—so deviations from the long-run trajectory fade only gradually. This slow return is consistent with the strong autoregressive pattern found in the ΔlnGDPagr equation, where three large and highly significant negative coefficients (−0.61, −0.55 and −0.58) point to pronounced internal inertia and mild cyclical reversals before the correction mechanism takes hold.

From a policy perspective, this pace cannot be read as outright weakness or full resilience; rather, it suggests a moderated form of resilience shaped by seasonal conditions, input rigidities and the structure of smallholder production. In concrete terms, a correction process that unfolds at this rhythm means that shocks associated with imported fertilisers, energy or global price swings are absorbed only slowly, heightening the need for policy instruments—credit flexibility, targeted support for input management and investment in irrigation—that can prevent temporary disturbances from turning into prolonged slowdowns. Seen through the lens of structural sustainability, the sector ultimately demonstrates an ability to return to equilibrium, although at a tempo that offers limited room for manoeuvre when facing external volatility.

Although the VECM provides a clear reading of long-run co-movement and the sector’s gradual return to equilibrium, the results should be interpreted with due caution: as a bivariate specification, the model captures the long-run external anchoring of agricultural GDP but cannot fully incorporate broader mechanisms—such as domestic cost pressures, investment cycles, climatic variability, credit conditions and public investment—that also shape short-term fluctuations in practice. Accordingly, the estimates reflect long-run external anchoring rather than a fully specified structural model. Nonetheless, the contrast between the strong and highly significant autoregressive coefficients in the agricultural equation and the near-zero, statistically irrelevant feedback effects identified in the TOT equation reinforces the internal–external asymmetry highlighted by the model, a feature that the broader literature often treats only conceptually.

This finding aligns with three strands of the literature. First, with evidence emphasising the heterogeneity of the TOT–activity link: the net effect depends on export–import composition and the financial environment [

16,

28,

29,

30,

43,

44,

45]. In this vein, analyses of integration and agricultural prices in globalised markets, together with studies on competitiveness and export diversification applied to the Peruvian agricultural sector, confirm that trade structure shapes the transmission of external shocks and sectoral vulnerability [

81,

82]. In our estimation, this is reflected in the insignificance of all ΔlnTOT lags and in the small magnitude of their coefficients—none exceeding |0.14|—which indicates that external shocks do not manifest as immediate changes in quarterly agricultural GDP. Instead, adjustment occurs through the error-correction term, as expected when the imported-input channel (fertilisers, energy, machinery) interacts with the export-income channel [

30,

31,

32]. Within that balance, episodes such as the Russia–Ukraine war—marked by surging fertiliser prices and supply tensions triggered by geopolitical shocks—provide a clear reading: costs may dominate the short run even when export prices are favourable [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Second, the results align with literature stressing the role of volatility and uncertainty—not only the level of TOT—on investment and production. The insignificant ECM coefficient in the TOT equation (

p = 0.407) and the very low explanatory power (R

2 = 0.156) indicate that their immediate dynamics respond to their own persistence—a pattern reflected in the significant and relatively large first lag of ΔlnTOT (0.371;

p = 0.0004)—and to global factors rather than to domestic feedbacks. This behaviour matches studies linking price and trade-policy uncertainty to investment cuts, hiring delays and reduced cross-border trade [

27,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Applied to agriculture, uncertainty surrounding imported inputs complicates planting calendars and budgets, affecting the short run even when the long-run anchoring remains [

31,

35,

52].

Third, the empirical pattern reinforces the relevance of the cointegration–ECM approach for agricultural markets: long-run anchoring coexists with heterogeneous adjustment speeds, as shown in applications for Turkey, Algeria, Malawi and Central and Eastern Europe [

38,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. The sectoral reading is clear: Peru’s agriculture co-moves with the external cycle but adjusts at a moderate pace, consistent with sowing–harvesting processes, supply rigidities and gradual technological adoption. The strong autoregressive component of agricultural GDP—reflected in the three negative and highly significant lags (−0.61, −0.55, −0.58;

p < 0.001)—also underscores internal cyclical regularities that shape how the sector absorbs shocks from imported inputs or global prices.

The robustness tests also provide interpretative nuances. The five-lag specification, which preserves the significance of the ECM coefficient (−0.040;

p < 0.001), mitigates the traces of serial correlation present at lower lag orders, supporting the stability of the adjustment mechanism. The absence of relevant ARCH effects points to controlled residual variances, and although multivariate normality is rejected, inference relies on accepted asymptotic properties in large samples. Finally, the decision not to include a COVID-19 dummy was grounded in the documented resilience of the agricultural sector [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

83] and in the statistical continuity of the deseasonalised series; the estimated equilibrium and adjustment speed remain free of visible breaks, consistent with institutional evidence on the sector’s 2020 performance [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

In terms of structural sustainability, the message is twofold. On the one hand, the existence of cointegration and a negative ECM in the agricultural equation reveal absorption capacity: the sector does not drift permanently after external shocks; it returns, albeit slowly, to its long-run path. On the other hand, the insignificance of TOT lags in the GDP equation (all

p > 0.14) and the weak responsiveness of TOT to GDP shocks (four insignificant coefficients) indicate that policy efforts should prioritise the management of critical inputs, countercyclical financing and productivity margins (logistics, irrigation, technology), precisely where external volatility hits first [

31,

36,

37,

49,

50,

51,

52]. In sum, the empirical evidence provided by this study aligns with the theoretical framework: the TOT matter for Peruvian agriculture not through mechanical quarterly transmission, but through the long-run anchor and the correction mechanism which—under volatile imported inputs—require buffering policies and a prudent reading of sectoral resilience over time [

84].

It should be noted that the literature does not offer directly comparable studies analysing the long-run link between the TOT and Peru’s agricultural GDP under a cointegration framework. Existing work has employed VECM, ARDL or cointegration tests to examine other aspects—price formation, shock transmission, market integration or productivity—but not the TOT–agriculture relationship [

85,

86]. This study fits within that methodological tradition and fills a specific gap by assessing, for the first time, the structural anchoring of agriculture to external relative prices. In that vein, the adjustment patterns identified here resonate with international evidence on input volatility, slow supply response and structural correction mechanisms, even if the literature has not modelled this exact combination of variables. As a first empirical approximation, the results offer a basis for future comparative applications in Latin America, Asia or Africa, where similar production structures and agricultural dependence prevail.

4.1. Policy Implications

The results obtained show that the performance of Peru’s agricultural sector is closely anchored to international trade conditions, given that the TOT operate as an exogenous variable imposing a long-run trajectory on agricultural GDP. This structural interdependence implies that the sustainability of the sector cannot be assessed solely through its internal dynamics, but also through its ability to absorb and adapt to external shocks that shape global relative prices. In this context, the evidence of cointegration and the significant adjustment reflected in the ECM highlight the need for policies aimed at reducing systemic vulnerability and strengthening long-term resilience. In particular, the slow correction pace implied by a 4% quarterly adjustment rate underscores the need for policy tools that help bridge this multi-quarter half-life and prevent temporary shocks from becoming prolonged output losses.

From a structural-sustainability perspective, progress along three complementary fronts becomes essential. First, market and product diversification, together with income-stabilisation mechanisms—supported, where relevant, by a broader portfolio of non-traditional crops, access to new export destinations and the use of sustainability and quality certifications—can soften the sector’s dependence on unfavourable movements in international prices [

87,

88]. Second, investment in agricultural technology, water-use efficiency and sustainable soil management—including the adoption of drip irrigation, small-scale reservoirs and regenerative practices that reduce reliance on imported fertilisers—can help reduce costs, enhance productivity and limit exposure to volatile imported inputs [

89,

90]. In addition, stabilisation schemes for fertiliser imports—such as forward procurement windows or public–private contingency stockpiles—could mitigate the recurrent instability of input availability and prices, which becomes particularly binding when adjustment to shocks unfolds over several quarters. Targeted programmes for fertiliser-use optimisation, concessional credit tied to irrigation upgrades, and accelerated depreciation for climate-resilient equipment would support farmers during the extended period required for shocks to dissipate.

Finally, reinforcing producer associations and improving access to specialised finance—including agricultural insurance and flexible credit lines, as well as cooperative-based lending instruments tailored to smallholders—enables smallholders to cope more effectively with the adjustments imposed by the external environment [

91]. In settings where deviations persist over several quarters, flexible repayment schedules, shock-responsive insurance triggers and revolving liquidity funds become particularly relevant, as they help maintain production continuity while the sector gradually returns to its long-run path. At the same time, the practical reach of these policy implications should be read within the limits of a bivariate specification: while the model identifies the long-run external anchoring imposed by the TOT, it cannot distinguish between specific channels—such as cost pressures, exchange-rate exposure or investment cycles—that shape on-the-ground decision-making. Taken together, these measures support the structural sustainability of the sector and contribute to a more robust and balanced response to international terms-of-trade cycles.

4.2. Future Research

Building on the limitations identified in this study, future research may broaden the analytical scope and deepen the understanding of how the TOT influence the structural sustainability of Peruvian agriculture. One avenue involves moving beyond the bivariate framework as more detailed sectoral series become available. Introducing variables such as the costs of imported inputs, credit conditions or public investment in water infrastructure would allow a more precise identification of the channels through which external shocks are transmitted to the agricultural sector. A disaggregated analysis by crop type—traditional versus non-traditional—would likewise help reveal heterogeneities that cannot be captured through an aggregate approach. A further step would be to explore systemic perspectives that extend beyond dynamic stability. Approaches that map interdependencies, complementarities and structural vulnerabilities across multiple agricultural dimensions could enrich the assessment of long-term resilience and offer a broader reading of sustainability than the one operationalised here. It would also be useful to apply this framework to economies with similar production structures—particularly in Latin America, Asia and Africa—where agriculture continues to play a central role and exposure to external shocks is comparable. Examining such cases would make it possible to assess the external validity of the results and develop a comparative research agenda on agricultural structural sustainability in countries that depend on the terms of trade.

5. Conclusions

The econometric results clearly show that Peru’s agricultural GDP maintains a long-run relationship with the terms of trade (TOT), a finding that confirms the first hypothesis and places the sector within a structural dynamic shaped by external cycles. The identification of a single cointegrating vector indicates that Peruvian agriculture does not evolve in isolation, but rather moves in line with the trajectory of international relative prices—a characteristic feature of primary-exporting economies and one that reflects a deeper form of structural anchoring. Even so, this interpretation should be viewed as an empirical approximation rather than a comprehensive structural characterisation of the sector. This interpretation gains additional relevance in a context of heightened global volatility, as it suggests that external conditions can gradually influence the sector’s productive path over time.

In the short run, the results reveal a clear distinction between the sector’s internal dynamics and the immediate effect of the TOT. The lags of ΔlnGDPagr display negative, large and highly significant coefficients, signalling a marked autoregressive pattern that captures the seasonality and intrinsic cycles of agricultural production. In contrast, the contemporaneous influence of the TOT on quarterly agricultural growth is weak and short-lived: under the selected specification, no short-run coefficient for ΔlnTOT attains statistical significance, indicating that external shocks do not exert an immediate or persistent impact on the sector’s quarterly dynamics.

The error-correction term constitutes the core interpretative element of the model. Its negative sign and strong significance show that the agricultural sector corrects deviations from the long-run equilibrium at a speed of around 4% per quarter. This directly supports the second hypothesis and establishes a gradual yet sustained adjustment process.

The third hypothesis is also strongly supported: the TOT do not adjust in response to shocks originating in the agricultural sector. The ECM associated with the ΔlnTOT equation is small and statistically insignificant, confirming their status as weakly exogenous variables within the system. This result is consistent with the structure of a small open economy, where international relative prices are determined in global markets.

The robustness checks further strengthen the stability of the model and justify selecting the five-lag specification as the main reference. The reduction in autocorrelation signals, the absence of conditional heteroskedasticity and the consistency of findings across specifications provide solid empirical backing. Likewise, the continuity of the agricultural series during 2020 and the absence of abrupt breaks support the decision not to include a COVID-19 dummy. Taken together, these results establish the core empirical contribution of the study: the TOT shape a long-run equilibrium to which agricultural GDP consistently returns, while short-run effects remain limited. Nonetheless, these patterns should be interpreted within the boundaries of a bivariate framework.

By offering empirical evidence of a long-run link between the TOT and agricultural GDP—an aspect scarcely documented in the Peruvian context and in similar agricultural economies—this study contributes to an area where the literature has shown persistent gaps. The cointegration–ECM framework provides a structural reading of how Peruvian agriculture internalises external conditions over time and highlights the mechanisms through which adjustment unfolds. Finally, the estimated dynamics portray a sector that adjusts, absorbs and persists even in a volatile global environment, offering a relevant analytical framework for understanding agricultural structural sustainability in open economies such as Peru’s.