1. Introduction

Species of the genus

Rubus L. are among the most widely cultivated berry crops worldwide [

1] and exhibit a high level of genetic diversity [

2]. They are valued not only for their desirable flavor qualities but also as an important source of nutrients and health-promoting compounds [

3,

4]. Raspberries are harvested both manually, as fresh dessert fruits intended for the retail market, and either mechanically or manually for processing purposes. Given the increasing labor costs and the decreasing availability of seasonal workers, which vary by cultivation region, the development of robotic systems for raspberry harvesting is highly desirable.

As various sectors of society and the economy move toward automation and autonomous solutions, robotic systems are increasingly being employed to perform complex tasks. In recent years, such systems have been widely implemented in agriculture, where they replace human labor traditionally regarded as highly time-consuming [

5], and, in particular, research on the optimization of agronomic practices in raspberry production is of great importance [

6,

7,

8].

Moreover, mass harvesting methods carry the risk of crop damage; therefore, selective harvesting where a robotic system identifies and picks only ripe fruits is increasingly being adopted. However, fruit detection and automated harvesting remain challenging tasks due to occlusions, variable lighting conditions, and color similarities. Automated agriculture, particularly in the domain of autonomous harvesting, continues to represent an open field of research requiring further development and refinement [

9]. With the advancement of science and technology, automated fruit harvesting integrates solutions from computer science, perception, control, and robotics, contributing to labor cost reduction and the development of modern, intelligent agriculture. Machine vision technology plays a particularly important role, as it is fundamental to the advancement of intelligent perception in agricultural systems. It is anticipated that continued technological progress, along with support from public policy, will significantly accelerate the development of automatic fruit harvesting systems [

10]. Visual perception technology is of fundamental importance in fruit-harvesting robots, enabling precise recognition, localization, and grasping of the fruits [

11]. In addition, key components include autonomous navigation, motion planning, and control, which constitute integral elements of the software architecture in robotic harvesting systems [

12]. Fruit and vegetable harvesting robots play a key role in the modernization of agriculture through their efficiency and precision. The rapid advancement of deep learning technologies has significantly stimulated research on robotic systems for fruit and vegetable harvesting; however, their practical implementation still faces numerous technical challenges. The variability and complexity of agricultural environments demand high robustness and strong generalization capabilities from detection algorithms [

13]. Deep learning, a branch of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), began to gain prominence in the early twenty-first century with the growing popularity of artificial neural networks, multilayer perceptrons, and support vector machines [

14].

The application of deep learning to fruit recognition has become one of the main directions of technological advancement in agriculture. These methods have significantly improved the accuracy of fruit identification under complex conditions, including variable illumination and partial occlusions [

15]. Among the various types of deep neural networks, convolutional neural networks (CNN) have been the most extensively studied. Although they have achieved remarkable success in experimental evaluations, many research challenges remain unresolved. The increasing complexity of contemporary CNN models entails the need for large-scale datasets and substantial computational power during training [

16]. A convolutional neural network is a deep, hierarchical feed-forward architecture based on the principles of local neuron connectivity, weight sharing, and dimensionality reduction, inspired by the concept of receptive fields in biological vision. As a deep learning model, it enables end-to-end learning, wherein features of the input data are progressively transformed into increasingly complex representations used for classification or other tasks. As the complexity of computer vision problems continues to grow, there is a rising demand for CNN models with higher performance and computational efficiency [

17,

18]. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) algorithm, developed in 2015, rapidly gained popularity due to its high efficiency. Unlike two-stage detectors, it performs object detection within a single neural network, formulating the task as a regression problem [

19]. It directly transforms the input image into bounding box coordinates and their corresponding class probabilities. The network divides the image into an S × S grid, where each cell predicts bounding boxes along with the associated class probabilities. As a result, the entire detection process is performed within a single convolutional neural network, enabling end-to-end optimization and achieving high processing speed while maintaining high accuracy [

20]. The YOLO algorithm has rapidly gained popularity in agriculture due to its high accuracy, operational speed, and compact network architecture. It has been applied to a wide range of tasks, including monitoring, detection, automation, and the robotization of agricultural processes. Although research on its applications in this field is developing dynamically, it remains fragmented and spans multiple scientific disciplines [

21].

The implementation of convolutional neural networks in raspberry cultivation remains very limited, clearly indicating the need for further research aimed at optimizing this technology for use in these crops. For this reason, the aim of our study was to evaluate the effectiveness of recent YOLO architectures for detecting raspberry fruits of red, yellow, and purple color varieties under field conditions. In addition to assessing detection accuracy, the study also compares the performance of these models to clarify how architectural differences influence detection capability and computational efficiency.

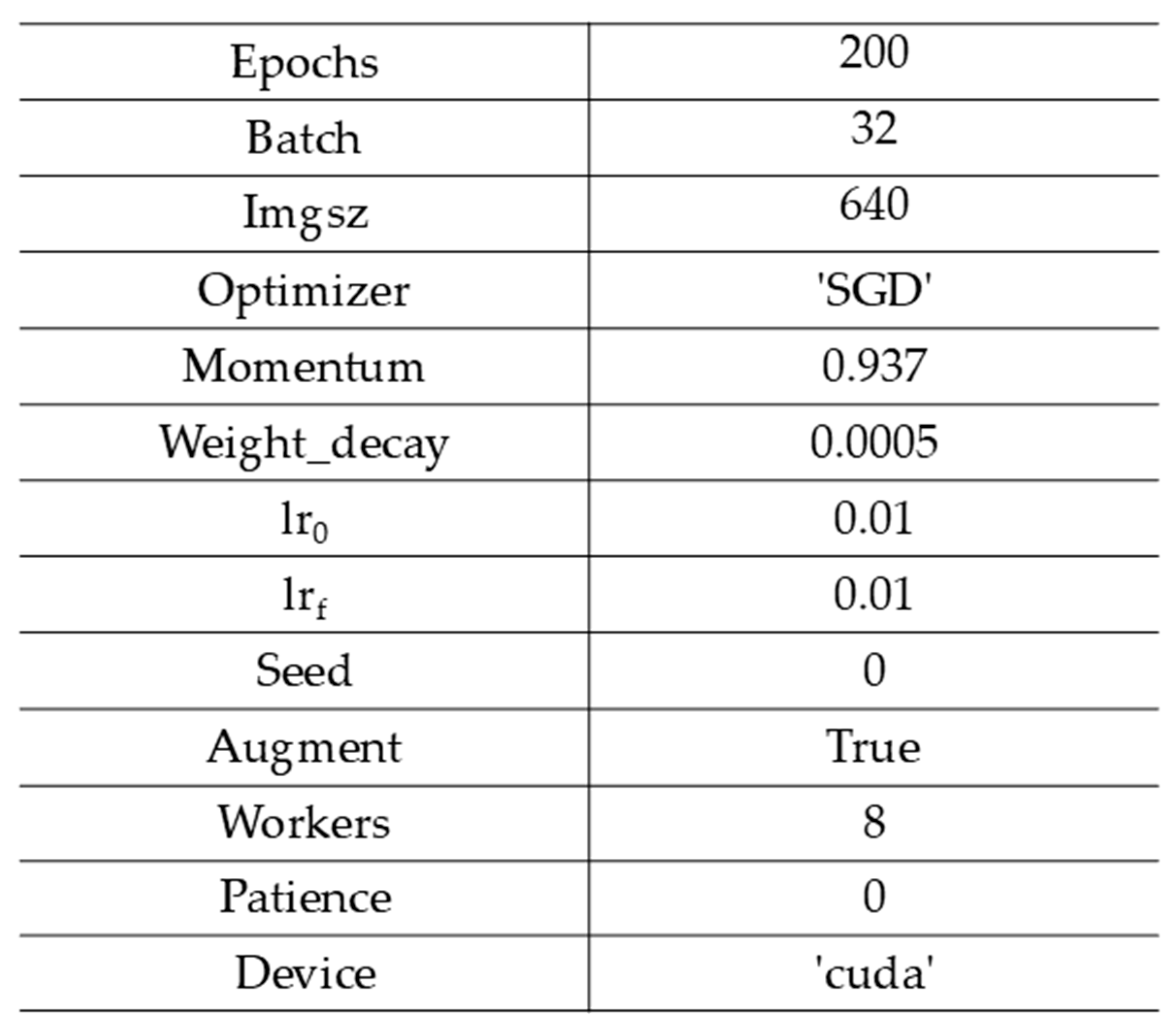

3. Results

All YOLO architectures achieved consistently high and closely aligned results in the raspberry fruit detection task.

Precision,

Recall, and overall detection accuracy remained highly stable across generations, reflecting the maturity of the underlying feature extraction designs. The smallest YOLOv8s variant already provided strong predictive balance, while subsequent versions offered only marginal fluctuations in performance. Among the models, the YOLOv9s and YOLO12s generations slightly improved

Recall, resulting in a marginal increase in the

F1-

score, whereas other architectures maintained nearly identical outcomes. The

mAP values at both lenient and strict thresholds confirmed that all models localized raspberry fruits with comparable reliability and robustness (

Table 3).

Figure 4 shows examples of red raspberry fruit detection using the trained YOLO12s model. Blue bounding boxes indicate detected fruits, and the numeric values represent confidence scores. All images were processed at 640 × 480 resolution (letterboxed to 640 × 640 during inference).

Across all evaluated models, detection performance for yellow raspberry fruits remained high and consistent, although with slightly greater variability between architectures, reflected in a wider spread of Precision, Recall, F1-score and mAP values compared with the red raspberry dataset.

The YOLO11s and YOLO12s variants achieved a balanced trade-off between

Precision,

Recall,

mean average precision and

F1-

Score, yielding the most consistent overall performance. Earlier architectures preserved strong generalization with negligible degradation in detection quality (

Table 4).

Figure 5 shows examples of yellow raspberry fruit detection using the trained YOLO12s model. Blue bounding boxes indicate detected fruits, and the numeric values represent confidence scores. All images were processed at 640 × 480 resolution (letterboxed to 640 × 640 during inference).

The detection of purple raspberry fruits produced slightly lower and more variable results across models, reflected in a wider spread of Precision, Recall, F1-score and mAP values compared with the red and yellow datasets.

All architectures maintained strong overall accuracy, yet

Precision and

Recall values revealed subtle trade-offs between sensitivity and selectivity. The YOLOv8s and the newest YOLO12s model achieved the most balanced predictions, while intermediate architectures exhibited minor fluctuations in performance stability. The

mAP metrics confirmed consistent detection accuracy, with only slight differences observed among the models. The stricter

mAP threshold values suggested a marginal decline in fine localization precision (

Table 5).

Figure 6 shows examples of purple raspberry fruit detection using the trained YOLO12s model. Blue bounding boxes indicate detected fruits, and the numeric values represent confidence scores. All images were processed at 640 × 480 resolution (letterboxed to 640 × 640 during inference).

The multi-class evaluation encompassing red, yellow, and purple raspberry fruits revealed highly consistent detection performance across all YOLO architectures. Differences between fruit classes were minor, indicating that the models maintained stable generalization across varying color distributions. Yellow and red fruits achieved closely aligned

Precision and

Recall values, with neither class showing a clear advantage. Purple fruits exhibited slightly lower scores overall, suggesting a modest increase in detection difficulty likely related to lower color contrast and higher spectral similarity with background foliage. Across generations, performance fluctuations were minimal and did not follow a strict upward trend, indicating that all tested architectures have reached a maturity level where further architectural modifications yield only marginal changes in detection accuracy. The observed uniformity across classes confirms that the multi-class training strategy effectively balances feature representation among fruit types, enabling consistent detection without significant class bias or degradation in localization precision. Among the evaluated architectures, the YOLO12s model achieved the highest average precision and

F1-

score, indicating a slight overall advantage in balanced detection performance. YOLO11s followed closely, showing strong consistency across all metrics and maintaining particularly stable

Recall. Earlier architectures such as YOLOv9s achieved competitive

Recall and localization accuracy but exhibited marginally lower precision, while YOLOv8s and YOLOv10s maintained balanced yet slightly lower average scores. These trends suggest that the most recent YOLO generations deliver modest but measurable improvements in detection quality, primarily reflected in enhanced precision and class stability (

Table 6).

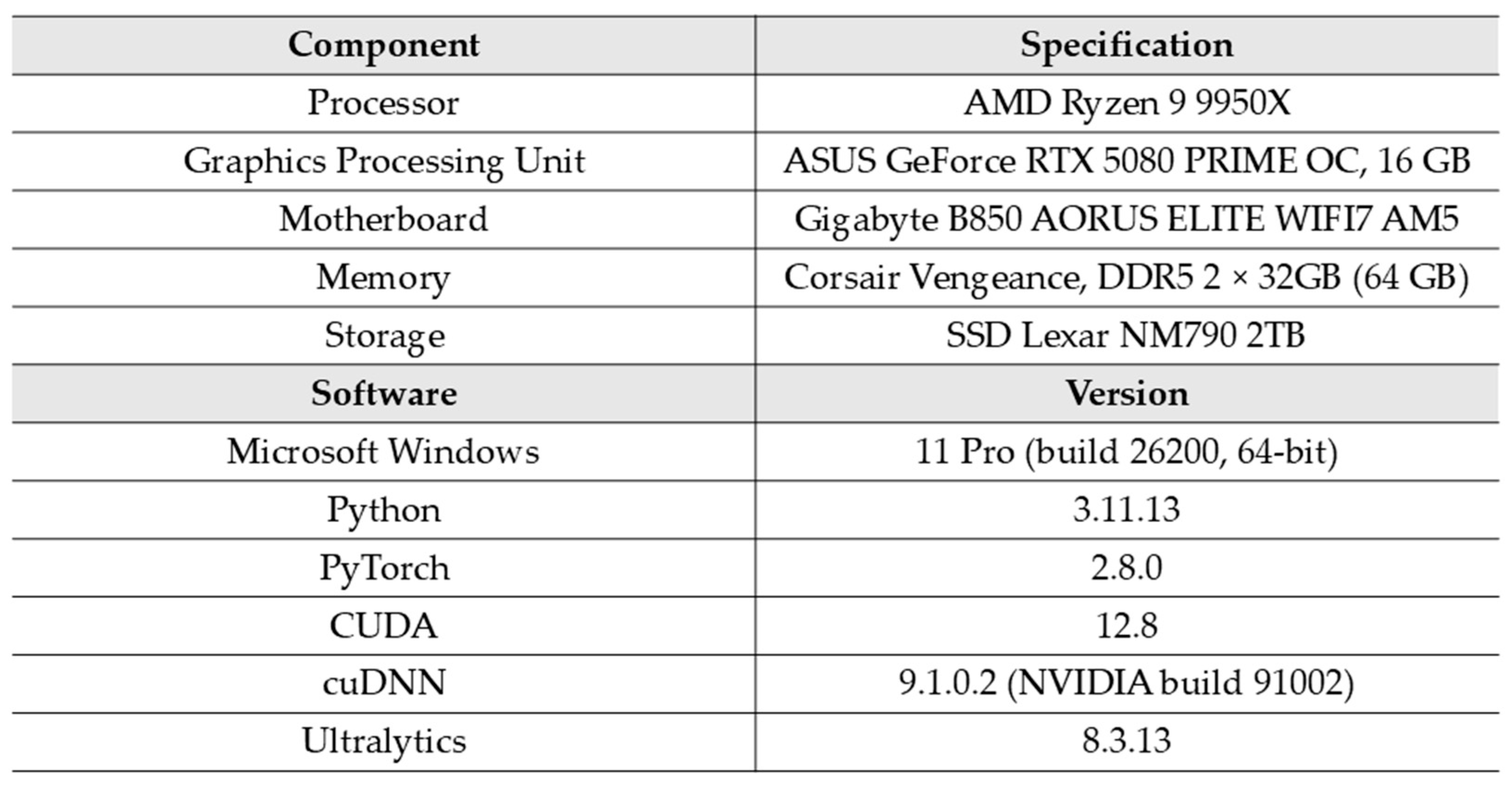

Table 7 presents the performance results of the models obtained using an RTX and the PyTorch framework. Across all fruit color datasets, inference speed and

Latency values followed consistent trends. The smallest YOLOv8s model achieved the highest frame rate and the lowest

Latency, confirming its strong computational efficiency on high-performance GPU hardware. In contrast, the YOLOv9s variant consistently exhibited the slowest processing speeds and the highest

Latency, which directly translated into the least favorable

Accuracy–

speed ratio among the evaluated models.

Architectures such as YOLOv10s and YOLO11s maintained stable throughput with only moderate increases in Latency compared to YOLOv8s, offering balanced efficiency between inference speed and predictive accuracy. The most recent YOLO12s model demonstrated a noticeable reduction in frame rate accompanied by a rise in Latency and accuracy–speed ratio, indicating a moderate computational overhead associated with its deeper architecture and refined feature extraction layers.

When considering dataset variations, all models demonstrated nearly identical performance across red, yellow, purple, and mixed-color subsets. The stability of FPS and Latency metrics across these subsets indicates that color variability within the fruit datasets had negligible influence on computational efficiency. Overall, YOLOv8s remained the fastest and most resource-efficient model, while YOLOv9s achieved the slowest execution, confirming a clear trade-off between architectural sophistication and inference speed.

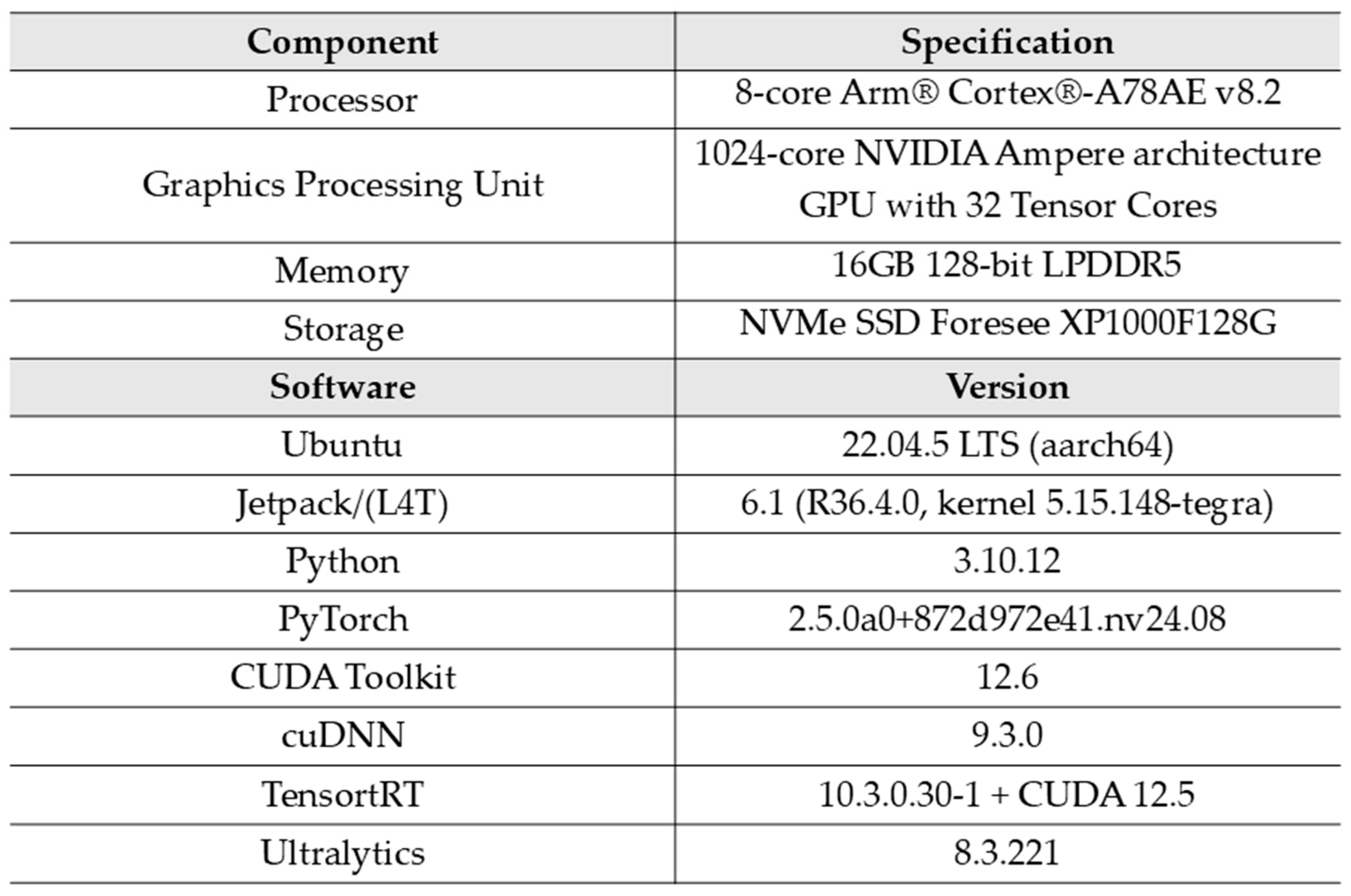

Table 8 presents the performance results of the models obtained using an Jetson Orin and the PyTorch framework.

Among the evaluated architectures, YOLOv8s consistently achieved the highest frame rate and the lowest Latency across all fruit color subsets, confirming its superior computational efficiency and suitability for real-time edge deployment.

YOLOv9s again represented the least efficient configuration, recording the lowest throughput and the highest Latency across every dataset. This translated directly into the highest Accuracy–speed ratio values, emphasizing the significant computational cost associated with this generation. In contrast, YOLOv10s and YOLO11s maintained stable performance, with only moderate increases in Latency relative to YOLOv8s, offering a balanced compromise between processing speed and architectural complexity. The YOLO12s model demonstrated a noticeable slowdown accompanied by a higher Latency and less favorable efficiency ratios, consistent with its deeper backbone and extended feature extraction stages.

Performance trends remained stable across all color datasets, with negligible variation in inference metrics between red, yellow, purple, and mixed-color subsets. This consistency suggests that spectral diversity in the input data did not significantly influence computational demands. Overall, the hierarchy of efficiency observed on RTX was preserved on Orin, but with reduced absolute performance, underscoring the trade-off between model depth and runtime efficiency under embedded hardware constraints.

Table 9 presents the performance results of the models obtained using an Orin and the TensorRT framework. Under TensorRT, YOLOv10s delivered the highest throughput and the lowest

Latency across all fruit subsets, yielding the most favorable accuracy–speed trade-off. YOLOv8s and YOLO11s formed a tight cluster with slightly lower frame rates and marginally higher

Latency, maintaining solid real-time behavior. YOLOv9s trailed these models with reduced speed and less efficient trade-offs, while YOLO12s was the slowest, reflecting the overhead of its deeper architecture on embedded hardware. Performance patterns were consistent across red, yellow, purple, and mixed-color data, indicating that input color variation did not materially affect computational efficiency.

Table 10 presents the improvement in model performance on the Orin using the TensorRT framework compared to the PyTorch framework. TensorRT optimization led to consistent performance gains across all evaluated YOLO models. The most pronounced acceleration was observed for the YOLOv9s architecture, which achieved an exceptional increase in frame rate and the largest proportional reduction in

Latency. The subsequent group of models—YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and YOLO12s also exhibited substantial improvements, though to a slightly lesser extent. Similar hierarchical patterns were observed across all evaluated metrics. The reduction in

Latency and the decrease in the

Accuracy–

speed ratio followed the same progression as

FPS improvements. The results remained uniform across all fruit color datasets, indicating that performance gains were driven by framework-level optimization rather than dataset characteristics.

4. Discussion

Fruit detection represents one of the most challenging applications of computer vision in agriculture. The appearance of fruits varies substantially across species and cultivars, driven by differences in color, morphology, surface texture, and growth structure. Illumination changes, occlusions caused by leaves and shoots, and background heterogeneity further increase visual complexity. As a result, developing reliable detectors requires large and diverse datasets, as well as architectures capable of capturing fine-grained features under variable outdoor conditions. At the same time, robust fruit detection is a fundamental prerequisite for automated harvesting and yield monitoring, making the evaluation of modern detectors based on convolutional neural networks in this context both technically and practically relevant.

Raspberry fruits represent one of the more demanding cases within this domain. Their small size, soft structure, and color similarity to surrounding foliage combined with frequent occlusion by leaves, shoots, and overlapping fruits, create conditions that are particularly challenging for object detectors. These characteristics make raspberries a suitable benchmark for assessing the maturity and robustness of modern YOLO architectures.

The publicly available datasets for training models designed for raspberry fruit detection are also very limited. One of the available datasets contains images of red raspberries captured under field conditions [

28], while another is intended for the automatic quality assessment of red raspberries in industrial applications [

29]. These collections cover only a narrow subset of red raspberry varieties and reflect a limited range of cultivation and industrial processing systems. As a consequence, they represent only a fraction of the visual variability encountered in commercial and small-scale raspberry production. Such constraints substantially limit the ability to train models with strong generalization capability, particularly given the wide diversity of red raspberry cultivars grown worldwide. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no publicly accessible datasets exist for yellow, purple, or black raspberries. The absence of such resources restricts current model development to a narrow subset of phenotypes and highlights the need for broader, multi-variety datasets that capture the full spectrum of fruit colors and field conditions. Given the significant morphological variability within Rubus species, such limitations constitute a significant barrier to training models with sufficient detection ability across species of this genus.The comparative analysis of YOLO architectures demonstrated that all evaluated models achieved consistently high and stable performance in raspberry fruit detection. The close alignment of

Precision,

Recall, and

mAP metrics across generations indicates that the feature extraction mechanisms of recent YOLO designs have reached a high level of maturity. The smallest YOLOv8s variant already provided a strong balance between detection accuracy and localization precision, suggesting that compact architectures can achieve competitive performance without extensive structural complexity. Successive generations introduced only marginal variations in predictive behavior. The consistency of

mAP values under both lenient and strict overlap thresholds further highlights the robustness of all models in localizing raspberry fruits.

When evaluated across fruit color subsets, detection remained uniformly strong. Yellow and red raspberries yielded nearly identical Precision–Recall characteristics, indicating reliable generalization across varying color distributions. Detection of purple fruits was slightly more challenging, showing minor decreases in Precision and Recall, likely due to reduced visual separability from background elements. Nevertheless, all models maintained high localization accuracy, with only small fluctuations in fine-grained detection performance.

The multi-class experiments confirmed the stability of YOLO detectors under shared training across fruit types. Performance differences between classes and model generations were minimal, suggesting that the current YOLO architectures effectively balance feature representation without introducing class-specific bias. The newest models, particularly YOLO12s and YOLO11s, exhibited the most uniform and balanced performance profiles, while earlier generations sustained competitive accuracy with only negligible degradation. Overall, the results indicate that the YOLO family has reached a performance plateau in this detection domain, where future improvements are likely to be incremental and driven by efficiency-oriented refinements rather than major architectural redesigns.

Species of the genus Rubus, including raspberries, remain poorly studied in terms of the performance of CNN-based algorithms, such as YOLO, in the context of fruit detection.

A few publications have confirmed the applicability of YOLOv5 and its improved version, HSA-YOLOv5, for detecting unripe, nearly ripe, and fully ripe raspberry fruits, demonstrating their effectiveness in this task [

30]. Given the limited harvesting periods for individual fruit species during each growing season, the ability to test models under simulated conditions is also important. Under such conditions, high detection accuracy of artificial fruits using YOLO algorithms has likewise been achieved [

31].

More recently, an enhanced YOLOv11n architecture has also been shown to accurately detect both unripe and ripe raspberry fruits, achieving improved overall performance compared with its baseline variant [

32]. Although fruit-ripeness classification is important in automated harvesting systems, its operational relevance depends on the harvesting strategy. In many practical scenarios, only fully mature fruits are candidates for picking; therefore, detecting unripe fruits may introduce additional computational load without providing functional benefit. For this reason, the present study focuses on the detection of harvest-ready fruits, while ripeness-stage classification remains a complementary direction for future work.

In the case of blackberries, the feasibility of detecting and evaluating three maturity levels of the fruits was confirmed by testing nine YOLO models, which demonstrated their effectiveness as real-time detection tools [

33]. High detection accuracy for blackberries at different ripeness stages was also achieved using YOLOv7 [

34].

The collective findings from previous studies on raspberries and blackberries illustrate that computer-vision research within the genus Rubus is still in its early stages. Existing models demonstrate promising performance, yet their development is constrained by limited datasets and the substantial phenotypic diversity that characterizes this genus. These factors highlight the need for broader, systematically collected image resources and further methodological work to advance robust fruit-detection systems for Rubus species.

The literature reports high effectiveness of YOLO-based methods in the detection of numerous fruit species belonging to genera other than

Rubus, confirming the broad adaptability of these approaches. promising results were obtained for blueberries [

35,

36,

37], citrus fruits [

38], macauba [

39], tomatoes [

40,

41], dragon fruit [

42,

43], pomegranates [

44,

45], apples [

46,

47], strawberries [

48,

49,

50,

51], grapes [

52,

53,

54], mangoes [

55,

56,

57], kiwifruit [

58,

59], cherries [

60,

61], plums [

62], avocados [

63], bananas [

64] and pears [

65]. In the case of Japanese apricots, the application of R-CNN, EfficientDet, RetinaNet, and SSD MobileNet models—based on convolutional neural networks—demonstrated their effectiveness as reliable methods for detecting fruits of this species [

66].

The successful application of CNN-based algorithms to fruit species exhibiting substantial variability in morphology, color, and surface characteristics indicates their strong generalization capability and confirms their potential as a universal framework for agricultural vision systems.

The evaluation of computational performance across hardware platforms and frameworks revealed consistent trends in inference efficiency among YOLO architectures. The results demonstrated a clear hierarchy of runtime performance that correlated with architectural complexity. Compact models maintained superior frame rates and minimal Latency, while deeper networks introduced measurable computational overhead.

On high-performance GPU hardware, the smallest YOLOv8s variant achieved the highest throughput and lowest Latency, confirming its efficiency in environments without strict computational constraints. The YOLOv9s architecture consistently represented the least efficient configuration, characterized by reduced frame rates and increased Latency that resulted in the highest accuracy–speed ratios. Intermediate models such as YOLOv10s and YOLO11s sustained balanced efficiency, maintaining strong throughput with moderate Latency growth. The latest YOLO12s model produced a noticeable slowdown, reflecting the processing cost associated with its extended feature extraction design.

The comparative analysis of YOLO architectures confirmed convergent trends with those reported in the literature. Recent YOLO generations revealed consistent efficiency patterns. YOLOv9 achieved high accuracy but struggled with small objects and computational overhead. YOLOv10 traded minor accuracy for notably faster inference and better handling of overlapping targets. The YOLO11s family maintained the best accuracy–efficiency balance, while YOLO12 introduced additional complexity without meaningful performance gain, confirming predictable scaling of computational cost across architectures [

67].

On the Orin platform, all models exhibited substantially reduced inference speed and increased Latency compared to desktop GPU execution, which is expected given the hardware constraints of embedded systems, but still based on our results, this type of device can also be deployed for real-time tasks. The overall performance decreased, but the relative hierarchy between models remained unchanged. This stability indicates that computational efficiency scales predictably across hardware classes.

TensorRT deployment further improved inference efficiency across all evaluated models; however, the magnitude of acceleration differed markedly between architectures. The largest proportional improvement was achieved by YOLOv9s, which exhibited the highest increase in frame rate and the greatest reduction in latency. This behavior reflects the architectural properties of YOLOv9, whose GELAN-based feature aggregation and deeper convolutional pathways form longer operator chains that TensorRT can fuse into highly optimized computational kernels.

Subsequent model generations—YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and YOLO12s—also demonstrated substantial acceleration gains, though slightly smaller than those observed for YOLOv9s. Their computational graphs still offer considerable opportunities for kernel fusion and memory-reuse optimization, yet their more streamlined operator layouts leave marginally less headroom for further acceleration.

In contrast, the YOLOv8s architecture showed the smallest relative benefit from TensorRT optimization. As one of the lightest models in the series, YOLOv8s attains high baseline efficiency in PyTorch, with limited potential for additional fusion or arithmetic-utilization improvements. A larger share of its total inference time is associated with lightweight layers and post-processing operations, such as non-maximum suppression, which TensorRT accelerates only modestly.

These findings align with the publicly documented architectural distinctions among YOLOv8s–YOLO12s in the Ultralytics model specifications, which report variations in block depth, feature-aggregation strategies, operator-path length, and overall computational complexity. The consistent decrease in Latency and Accuracy–speed ratio followed the same hierarchical order as the improvements in FPS, confirming that TensorRT optimization enhanced inference speed without disrupting the relative performance structure among architectures.

A recent benchmarking study of five deep-learning inference frameworks on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin also provides a relevant reference point for interpreting the performance differences observed in this work. Evaluating pretrained models spanning both convolutional and transformer architectures including ResNet-152, MobileNetV2, SqueezeNet, EfficientNet-B0, VGG16, Swin Transformer, and YOLOv5s. The authors reported that TensorRT consistently achieved the lowest inference latency and highest throughput. These gains were enabled by its statically compiled execution engine, FP16 computation, and extensive operator fusion, albeit at the cost of increased power consumption. PyTorch, in contrast, offered a balanced trade-off between efficiency and usability, maintaining low latency and strong throughput through its cuDNN-accelerated dynamic computation graph [

68]. The behavior observed in our experiments aligns with these findings. TensorRT provided substantial acceleration on the Orin especially for architectures with deeper operator chains while PyTorch remained competitive as a general-purpose and portable deployment optionPrevious studies have shown that inference is consistently faster with TensorRT than with the native PyTorch runtime, and this difference becomes more pronounced for complex models or constrained hardware. Embedded NVIDIA Jetson devices enable real-time detection but must be matched to the computational demands of the specific YOLO variant [

69].

Overall, the findings demonstrate that YOLO architectures maintain predictable computational behavior across hardware environments. Framework-level optimization significantly enhances runtime efficiency, while architectural scaling continues to impose proportional computational costs. These results emphasize that efficiency improvements are increasingly governed by optimization techniques rather than fundamental model redesigns.

Beyond architectural comparisons, the practical value of deploying YOLO models in their out-of-the-box form also merits attention. Although recent research frequently pursues domain-specific modifications such as attention mechanisms, enhanced feature fusion, or redesigned neck and head structures standard YOLO implementations provide several advantages that are highly relevant for agricultural and robotic systems. These include rapid deployment without the need for architectural tuning, stable and predictable inference behavior across hardware platforms, broad compatibility with existing software ecosystems, and reduced engineering overhead during system integration. Our results show that even unmodified YOLO architectures deliver high detection accuracy and strong generalization across fruit colors, indicating that off-the-shelf models already meet the operational requirements of many field-level applications. For end users and technology implementers, this reliability and ease of deployment make baseline YOLO models an effective and practical foundation for real-world agricultural vision pipelines.

The results also highlight practical implications for deployment. The RTX offered the highest inference speed, but its size, power requirements, and need for work environmental protection limit its suitability for field use. The Orin, although slower, provides a compact and energy-efficient platform designed for edge applications and can be integrated into ruggedized housings. These characteristics make Jetson-class devices a more realistic choice for in-field agricultural systems, where mobility, environmental exposure, and limited power availability are key constraints.

This study also has several limitations. Our analysis focused solely on 2D object detection; emerging directions such as 3D localization and depth-aware fruit modeling were not examined. The S25 smartphone and handheld gimbal were used exclusively for data acquisition rather than as a deployment platform, serving only to provide consistent field imagery. Accordingly, the conclusions of this work refer to the performance of the evaluated neural-network models and hardware accelerators not to the suitability of the acquisition device for real-world operation. We also did not address ripeness classification, which remains an active research topic. Finally, all experiments were conducted using a single RGB camera. Other sensing configurations, such as stereo or multispectral cameras, may further improve robustness in occluded or visually complex field environments. The balance between high detection accuracy and processing speed is particularly important in robotic implementations, where computational resources are often limited. In parallel with the progress of machine vision algorithms for fruit detection, robotic harvesting systems leveraging these advances are rapidly evolving. Recent studies have also explored their application to raspberry harvesting tasks.

At present, robotic platforms for automated fruit harvesting are under active development. Their success will also depend on robust and efficient machine vision systems, capable of detecting and localizing fruits under complex field conditions, including raspberries.

Automated agriculture, particularly autonomous harvesting using robotic systems, remains an open and evolving research domain that presents numerous challenges and opportunities for the development of novel solutions [

9].

In the case of raspberries, considerable attention has been devoted to the design of end-effectors intended for their harvesting, as the delicate structure of the fruit poses a major challenge in the development of robots designed for this purpose [

70,

71]. This confirms the need to develop solutions that enable highly effective and accurate detection of raspberry fruits, which will help minimize damage during harvesting and reduce the number of missed fruits. Ultimately, this can also prevent delayed harvesting that might otherwise render the fruits unsuitable for consumption.