1. Introduction

As a key link in the terrestrial carbon cycle, the dynamic changes of agricultural ecosystem respiration directly affect the regional and global carbon balance. In the context of increased climate change, accurate quantification of agro-ecosystem respiration and its response mechanism to climate change is of great significance for understanding the carbon cycle process, predicting climate change trends, and formulating agricultural emission reduction strategies [

1,

2]. Although the traditional ground observation method can provide accurate point data, it has obvious limitations in large-scale and continuous monitoring, and it is difficult to meet the needs of systematic cognition and model prediction [

3,

4].

In recent years, the rapid development of remote sensing technology has provided a new way to break through this bottleneck. Multi-platform, multi-spectral and high spatial-temporal resolution remote sensing data have brought unprecedented opportunities for the spatio-temporal dynamic inversion of ecosystem respiration and its driving mechanism analysis [

5]. However, although remote sensing technology has made significant progress in ecosystem monitoring, it is still an emerging field full of specific challenges to apply its system to the study of agricultural ecosystem respiration, especially to reveal its response to climate change [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The key challenges include the following: (1) The scale mismatch between in situ flux observations (such as vorticity covariance tower) and satellite sensor footprints, which complicates direct verification and model calibration; (2) it is difficult to distinguish autotrophic respiration (plants) and heterotrophic respiration (soil microorganisms) from the mechanism based on remote sensing data alone, which limits the in-depth understanding of the process [

9,

10]; (3) effective fusion of multi-source remote sensing data (e.g., optical, thermal infrared, microwave) and their integration with climate drivers and process-based models to reduce estimation uncertainty [

11,

12,

13].

Especially since 2021, the deep integration of artificial intelligence technology and the breakthrough of the multi-source data assimilation method have promoted the important transformation of the research paradigm in this field, showing an important transformation from single observation to multi-process coupling, from phenomenon description to mechanism analysis. This period marks the initial stage of the rise and rapid development of this interdisciplinary field, enabling us to capture the formation of its knowledge structure and the evolution of its research paradigm from its source [

9,

10]. However, there is still a lack of systematic review of the overall development context, research hotspots and frontier directions in this field. The traditional narrative literature review is limited by subjectivity and coverage, and it is difficult to fully reveal the evolution of knowledge structure, the characteristics of the cooperation network and the quantitative law of research focus transfer [

11,

14].

In order to make up for these gaps, based on the CiteSpace bibliometric method, this study conducted a quantitative analysis of 222 related literature included in the core collection of Web of Science from 2021 to 2025, aiming to answer the following scientific questions: (1) What are the temporal evolution characteristics and cooperative network structure of remote sensing research on the impact of climate change on agro-ecosystem respiration? (2) What are the key research topics and frontier directions in this field? (3) How do new technologies such as machine learning and multi-source data fusion promote method innovation and paradigm transformation in this field? By constructing a keyword co-occurrence network, a national cooperation map and burst word detection, this study systematically analyzes the knowledge structure, development path and research frontier in this field.

The significance of this study is as follows: in theory, the dynamic evolution law of remote sensing research on agricultural ecosystem respiration is revealed by the bibliometrics method, which fills the shortcomings of traditional review; in terms of methods, it shows the quantitative analysis potential of CiteSpace in the cross-research of climate change and remote sensing, and promotes the innovation of interdisciplinary methods. In practice, identify research gaps and development directions, provide scientific basis for agricultural carbon management and climate change adaptation strategy formulation, and provide technical support for achieving sustainable development goals (SDG13 climate action, SDG15 terrestrial ecology) [

15,

16].

2. Study on the Background

As global climate change continues to affect agricultural ecosystems, the dynamic changes of agricultural ecosystem respiration and its response mechanism to climate change have become the core issues of current research. As an important part of the terrestrial carbon cycle, the fluctuation of agricultural ecosystem respiration directly affects the regional and global carbon balance [

8,

17,

18,

19]. Although traditional ground observation methods can provide accurate point data, they have obvious limitations in large-scale spatial representation and continuous monitoring capabilities, such as low spatial representation, high cost and difficulty in capturing intraseasonal changes, which limit the in-depth understanding of the overall behavior of the system and the further improvement of model prediction capabilities [

3,

4].

In recent years, the rapid development of remote sensing technology has opened up a new path to solve the above problems. The wide application of multi-platform, multi-spectral and high spatio-temporal resolution remote sensing data provides unprecedented technical support for the spatio-temporal dynamic inversion of ecosystem respiration and its driving mechanism analysis. It is worth noting that although remote sensing technology has shown great potential in ecosystem monitoring, its application to the study of agricultural ecosystem respiration, especially to reveal its response to climate change, is still in the preliminary exploration stage [

5,

20,

21]. Since 2021, with the deep integration of artificial intelligence technology and the breakthrough of multi-source data assimilation methods, such as the wide application of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 9 data, and the emergence of deep learning models for carbon flux estimation, the research in this field has shown an important shift from single observation to multi-process coupling, from phenomenon description to mechanism analysis.

Although remote sensing technology has made significant progress in ecosystem monitoring, it is still in its infancy in focusing on agricultural ecosystem respiration and systematically exploring its response to climate change. Especially since 2021, with the deep integration of artificial intelligence technology and the breakthrough of the multi-source data assimilation method, the research in this field has shown an important transformation from single observation to multi-process coupling, from phenomenon description to mechanism analysis [

22,

23,

24]. Based on the latest international literature from 2021 to 2025, this study systematically reviews the remote sensing research methods, hotspots and frontiers of agricultural ecosystem respiration under the context of climate change, aiming to reveal the knowledge structure, cooperation network and development path of this emerging field, and provide a theoretical basis and methodological support for agricultural carbon management in response to climate change. The significance of this study lies in the theory that the dynamic evolution law of agricultural ecosystem respiration remote sensing research is revealed by the bibliometric method, which makes up for the deficiency of traditional review; in terms of methodology, it shows the quantitative analysis potential of CiteSpace in the cross-study of climate change and remote sensing, and promotes the innovation of interdisciplinary methods.

3. Data Sources and Research Methods

3.1. Data Source

The data source is the Web of Science core collection. The search source time is from 2021 to the present. The search format in the WoS database is “TS = (“remote sensing” OR “satellite*” OR “UAV” OR “drone*” OR “MODIS” OR “Landsat” OR “Sentinel” OR “hyper-spectral” OR “multi-spectral” OR “NDVI” OR “EVI” OR “LAI”) AND (“climate change” OR “climatic change” OR “global warming” OR “temperature increase” OR “precipitation change” OR “elevated CO2”) AND (“agricultural ecosystem respiration” OR “agroecosystem respiration” OR “soil respiration” OR “ecosystem respiration” OR “Reco” OR “Rh” OR “carbon dioxide flux” OR “CO2 flux”)”. The data deadline is 8 September 2025. After manual deduplication, 222 articles were obtained in the WOS database. It should be noted that the selected remote sensing indices (such as NDVI, EVI and LAI) are widely considered to be key proxies for vegetation activity and productivity and are closely related to ecosystem respiration. Although other indices (e.g., LST, SAVI) are also valuable, our research focuses on the most commonly used indices with carbon flux and respiration studies.

The core collection of Web of Science was selected as the only data source because it is famous for its high-quality, peer-reviewed literature, and its standardized data format is very suitable for bibliometric analysis using tools such as CiteSpace. We manually screened the search results to remove duplicate and irrelevant literature and finally obtained a collection of 222 articles focusing on this research topic.

3.2. Research Methods

This study used CiteSpace 6.4.R1, VOSviewer 1.6.20 visual analysis software, combined with Origin mapping software, to scientifically measure a total of 222 English literature on the theme of remote sensing research on the impact of climate change on agricultural ecosystem respiration [

25,

26,

27]. The core of this study uses CiteSpace 6.4.R1 software to draw and interpret the knowledge map. The specific parameters and processes are as follows:

Time slice: set the analysis time period (2021–2025) to one time slice per year.

Node type: according to the research purpose, ‘Country’ (country), ‘Institution’ (institution) and ‘Keyword’ (keyword) are selected as network nodes to construct a cooperative network and a co-occurrence network, respectively.

Literature screening criteria: in each time slice, set the top 25 literature data (g-index: k = 25) [

26].

Network pruning and clustering: In order to improve the clarity of the network map and the readability of the key structures, the ‘Pathfinder’ (Pathfinder network) and ‘Pruning sliced networks’ (Pruning sliced networks) algorithms are selected to prune the network. Keyword clustering analysis uses the LLR (Log-Likelihood Ratio) algorithm to automatically identify clustering labels.

Clustering quality evaluation: As described in the original article, the keyword clustering results are quantitatively evaluated by the modularity value (Q value) and the average Contour value (S value). When Q > 0.3, it shows that the network community structure is significant; when S > 0.5, it is considered that the clustering is reasonable, and S > 0.7 means that the clustering is convincing. The clustering results of this study meet these criteria and confirm the validity of the analysis [

28,

29].

In order to more intuitively show the intensity of cooperation between countries, this study assists in using VOSviewer to extract national cooperation network data (generating data files containing national nodes and cooperation links). Subsequently, the data were imported into Origin software to draw a national co-occurrence chord diagram. In the string diagram, the arc length represents the number of documents issued by each country, the connection line between countries represents the cooperative connection, and the thickness of the connection directly reflects the intensity of cooperation.

3.3. Literature Screening Criteria

In order to ensure the relevance and quality of the literature analysis, we carried out a two-step screening process including clear inclusion and exclusion rules for the initial search results.

Inclusion rules were as follows: Research must focus primarily on agro-ecosystems (including farmland, orchards and managed grasslands); remote sensing technology must be used as a core method for monitoring or analyzing ecosystem respiration (or its components, such as soil respiration); research must clearly investigate the impact or correlation of climate change factors (such as temperature, precipitation and elevated carbon dioxide concentration); articles must be peer-reviewed, original research articles or review articles.

Exclusion rules were as follows: only focus on natural ecosystems (such as primitive forests, natural tundra) and no agricultural management research; remote sensing only plays a secondary or auxiliary role, or is only based on traditional ground observation research; publications are not written in English, or documents of conference abstracts, editorials, books, etc.; it mainly focuses on the development of technical sensors but not directly applied to the study of ecological respiration.

All authors independently screened according to the title and abstract, and any differences were resolved through discussion. This rigorous process eventually formed the final data set of 222 articles for bibliometric analysis.

4. Analysis of the Basic Characteristics of Literature

4.1. Publishing and Publishing Trends

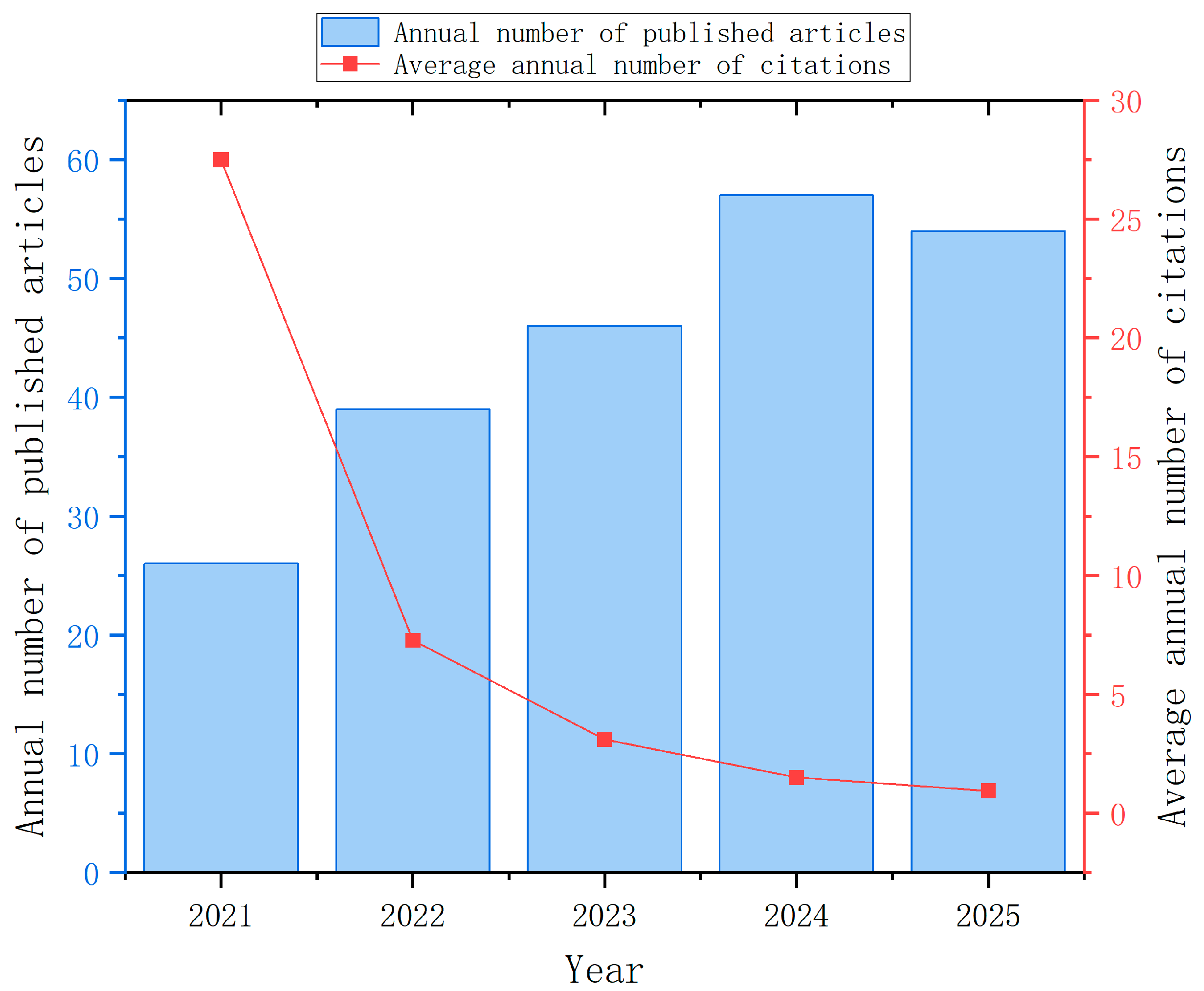

In order to reveal the research activity and development stage in this field, we first analyze the trend of annual publication volume and average citation frequency, and the results are shown in

Figure 1. We quantitatively analyzed the remote sensing literature (2021–2025) concerning climate change impacts on agricultural ecosystem respiration. The annual publication counts and citation patterns offer clear insights into the field’s research activity, academic impact and technological evolution. Through a systematic analysis of 222 articles (

Figure 1), the research evolution displays distinct stage characteristics, which are interpreted through both total and average citation metrics [

30,

31].

Preliminary Development Stage (2021–2022): This foundational phase was characterized by a low annual publication volume. However, the notably high average citations per paper during this period signify a strong initial academic impact, indicating that these early studies captured significant scholarly attention and laid the groundwork for subsequent research. Rapid Growth Stage (2023–2024): Coinciding with the widespread adoption of remote sensing technology and increasing concern over climate change, the annual publication count increased significantly. This surge in output led to a growth in the total number of citations, reflecting the field’s entry into a critical period of knowledge accumulation and expanding influence. However, the influx of new publications also resulted in a temporary decline in the average citations per paper, a typical phenomenon in rapidly expanding scientific fields where citation accumulation lags behind publication growth [

30,

31]. Development Deepening Stage (2025): In this most recent phase, the annual publication volume shows signs of stabilization. It is important to note that, contrary to our initial description, the per-article citation count for 2025 (based on available data) does not show a continued climb relative to the peak in 2022, as is visually evident in

Figure 1. This stabilization in both volume and average citation metrics may suggest a maturation of the research field. A note on 2025: As the year was not concluded at the time of analysis, this period may also represent a consolidation phase within the broader rapid growth trend.

The observed trajectory aligns with the early-to-mature stage development pattern described by Price’s literature growth theory [

30]. Simultaneously, it illustrates the progression of remote sensing technology in this field, from initial methodological exploration to deepened application. The temporary dilution of average citations, a common feature in expanding disciplines, occurs as scholarly recognition gradually catches up with the rapid increase in new publications [

23,

25,

28,

30,

31].

4.2. Collaborative Network Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of National Cooperation Network

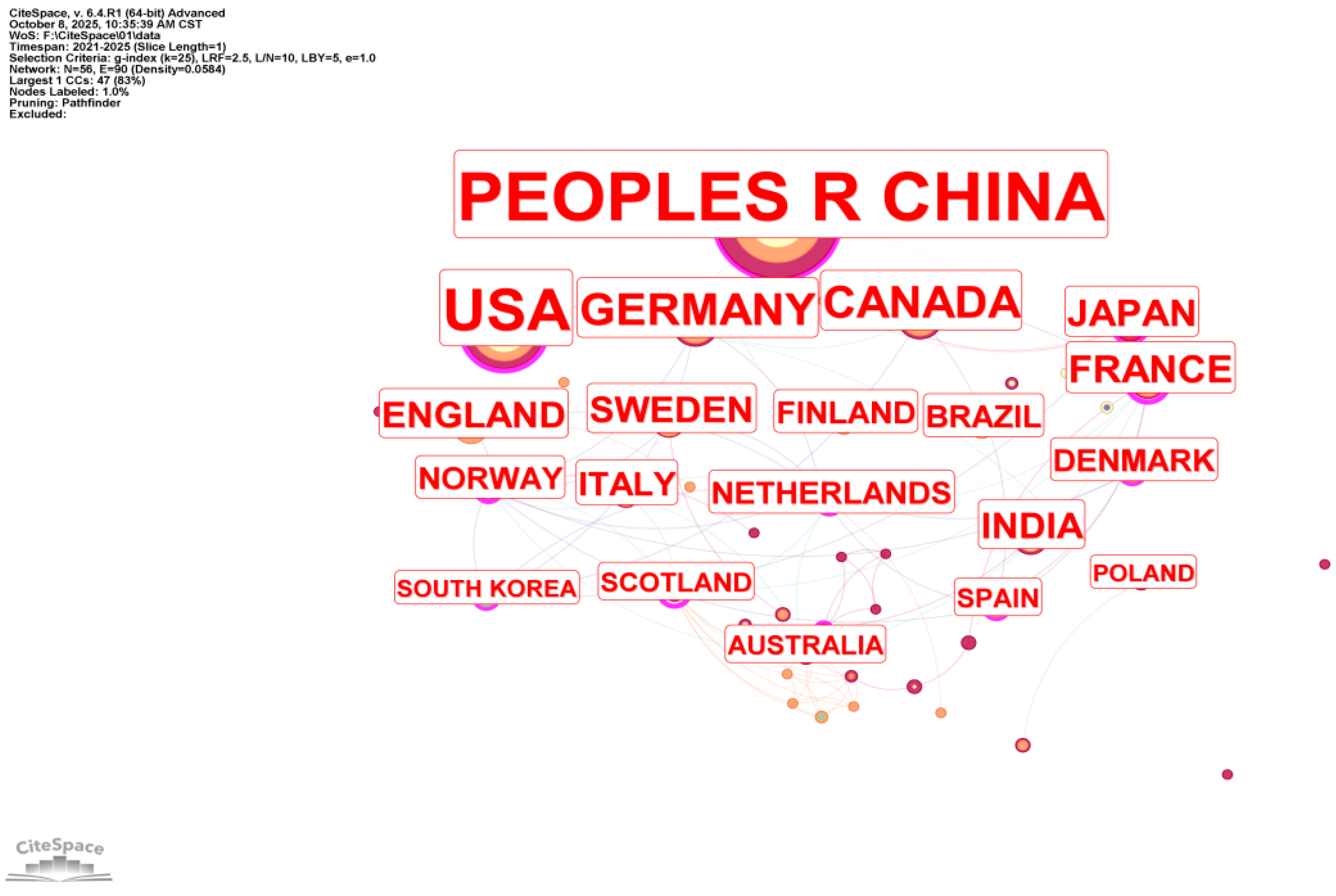

The analysis of the national cooperation network based on CiteSpace (

Figure 2 and

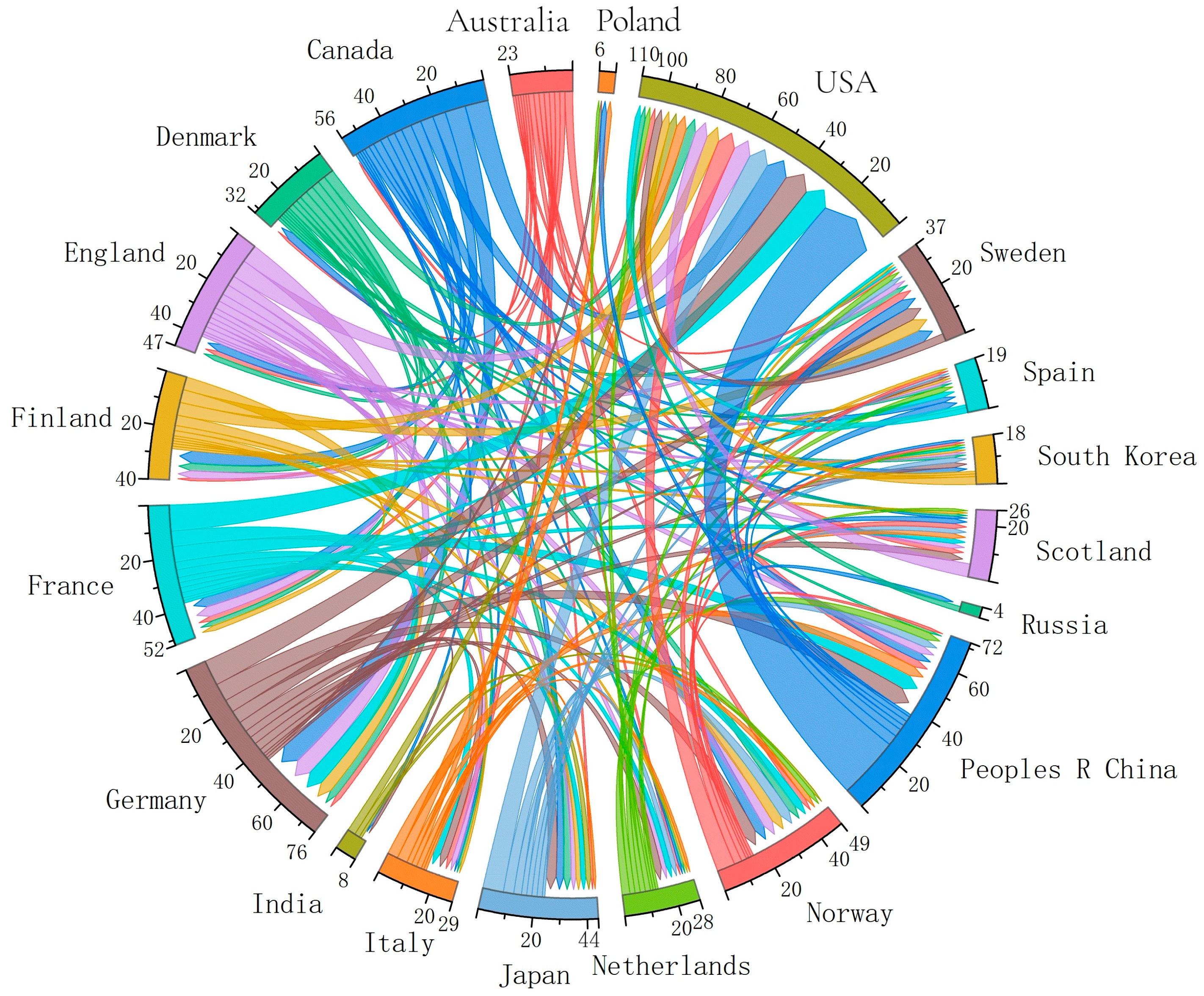

Figure 3) reveals the global cooperation pattern of this study.

Figure 3 shows the international cooperation network represented by the top 20 countries in the form of a string diagram. China occupies a dominant position in the field of remote sensing research on the impact of climate change on agricultural ecosystem respiration (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). From the perspective of national data statistics (

Table 1), China’s highlighting frequency is as high as 135 times, far more than other countries, showing its core position and academic influence in this field. Although the United States has the second-highest frequency of salience (60 times), it also maintains a very high betweenness centrality (0.34) among the most prolific countries. This indicates that the USA not only produces a large volume of research but also plays a critical role as a central hub in the global cooperation network. It is important to note that betweenness centrality is one key metric for assessing a country’s role as a connector; while countries like France (0.49), Norway (0.58) and Scotland (0.63) have higher centrality, their overall publication volume is lower, illustrating different strategic positions within the network.

Table 1 lists in detail the frequency, betweenness centrality and other indicators of the top 20 countries. Among them, betweenness centrality is a key indicator to measure the ability of a node to connect different communities in the network; the higher the betweenness centrality of a node, the more important it is as a ‘hub’ or ‘intermediary’ of cooperation.

From the perspective of international cooperation patterns, a multi-center cooperation network has been formed with China and the United States as the core and Germany, Canada, France, Japan and other countries actively participating. It is worth noting that countries such as France (betweenness centrality 0.49), Norway (0.58) and Scotland (0.63) have higher betweenness centrality, indicating that these countries play a key role in promoting cross-regional scientific research cooperation, although their publication volume is not prominent.

In terms of cooperation intensity, China has established a close cooperation relationship with the United States, Canada, Germany and other countries (the connection line in

Figure 3 is relatively thick). Although India, Brazil and other countries have a certain number of publications, the betweenness centrality is 0, indicating that their international cooperation participation is low, and the research activities are mainly domestic. In addition, although Scotland, Spain, South Korea and other countries have a high degree of betweenness centrality, they have issued fewer papers, reflecting their role as ‘liaisons’ in international cooperation rather than major producers.

The formation of this cooperation pattern may be due to the following reasons: (1) China has invested significantly in agricultural remote sensing technology and ecosystem carbon flux monitoring, which has promoted the high concentration of local research; (2) European and American countries have traditional advantages in climate change models and multi-platform remote sensing data fusion, which promotes cross-regional methodological cooperation; (3) some countries (such as India and Brazil) pay more attention to the specific problems of their own agro-ecosystems, and the impetus for international cooperation is relatively limited.

In general, the international cooperation network in this field presents the structural characteristics of “China–US dual-core leadership, European node connection, and local participation of emerging countries,” reflecting the division of labor and cooperation of global scientific research forces in dealing with climate change and agricultural ecological monitoring issues.

4.2.2. Analysis of the Main Research Institutions

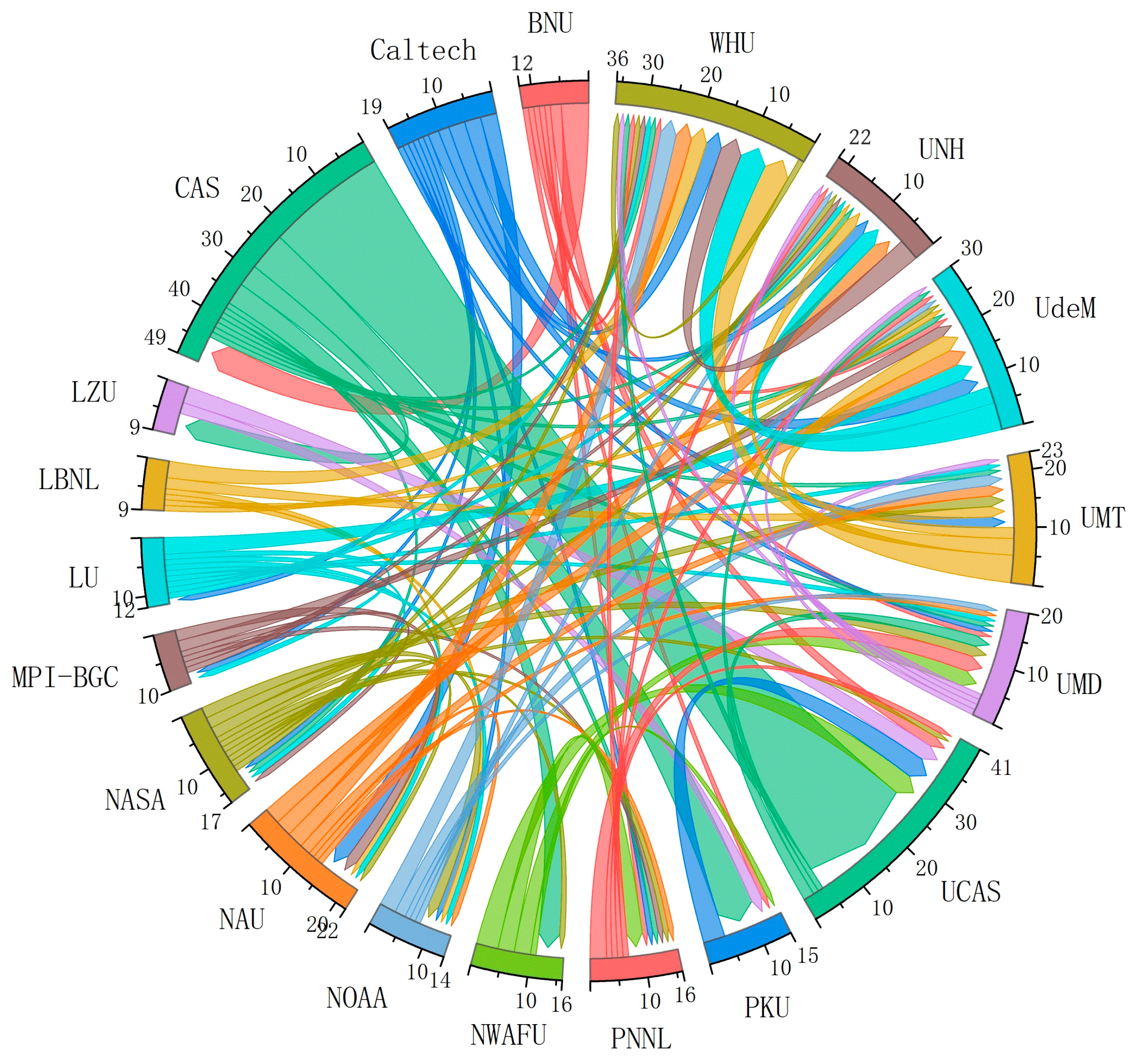

The cooperation network between research institutions is shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The network reveals the core research forces and their collaborative relationships. The specific institutional publications and centrality indicators are shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3. The field of remote sensing research on the impact of climate change on agricultural ecosystem respiration presents the characteristics of ‘multi-polar collaboration and Sino-US dominance’ (

Figure 4). From the perspective of institutional data statistics (

Table 3), the Chinese Academy of Sciences system occupies a leading position in the world. Among them, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (53 articles) and its subordinate universities (23 articles) and the Institute of Geographic Science and Resources (17 articles) constitute China’s core research force in this field, forming a research cluster with Beijing as the core and radiating the whole country.

American research institutions also show strong research strength and cooperative influence. Although the United States Department of Energy (DOE) has published only 13 papers, its betweenness centrality is as high as 0.54, showing its key role in the global cooperation network. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA, betweenness centrality 0.08) and the University of California system (betweenness centrality 0.25) play an important role in the supply of remote sensing data and interdisciplinary research methods, respectively, forming a research system promoted by government scientific research institutions and top universities.

Among the European scientific research institutions, institutions such as the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS, betweenness centrality 0.22) and the German Mapuche Society play an important role as a bridge in international cooperation, especially in promoting Eurasian research collaboration.

From the perspective of the spatial structure of the research network (

Figure 4), three typical research clusters have been formed: China’s national-level scientific research cluster, with the Chinese Academy of Sciences as the core, combined with universities such as Beijing Normal University and Peking University, focusing on basic theories and method innovations such as remote sensing inversion algorithms and ecosystem carbon flux models; a comprehensive research network in the United States led by government agencies such as DOE and NASA, combined with universities such as the University of California system, focusing on multi-platform remote sensing data fusion and global climate change response research; China–EU Collaborative Research Node, represented by CNRS in France and Max Planck Institute in Germany, through cooperation with Chinese scientific research institutions, promote the application and verification of remote sensing technology in agro-ecosystem monitoring [

6,

7,

29].

The formation of this institutional cooperation pattern, on the one hand, reflects China’s high investment and system layout in the field of agricultural remote sensing and carbon cycle research, and on the other hand, it also reflects the traditional advantages of the United States in space-to-earth observation technology and climate change research. It is worth noting that the active participation of agricultural universities such as Northwest A&F University shows the application orientation and regional characteristics of China in the research direction [

24,

28].

To advance the field, the following strategic collaborations are critical: It is imperative to deepen Sino-American collaboration, focusing on data sharing and reciprocal model recognition. European research institutions should be engaged to play a pivotal bridging role in validating methodologies and facilitating regional implementation. Greater involvement from agricultural universities and local research bodies is essential to bolster the translational capacity of scientific findings.

4.3. Keywords and Hot Frontier Research Analysis

4.3.1. Keyword Clustering Analysis

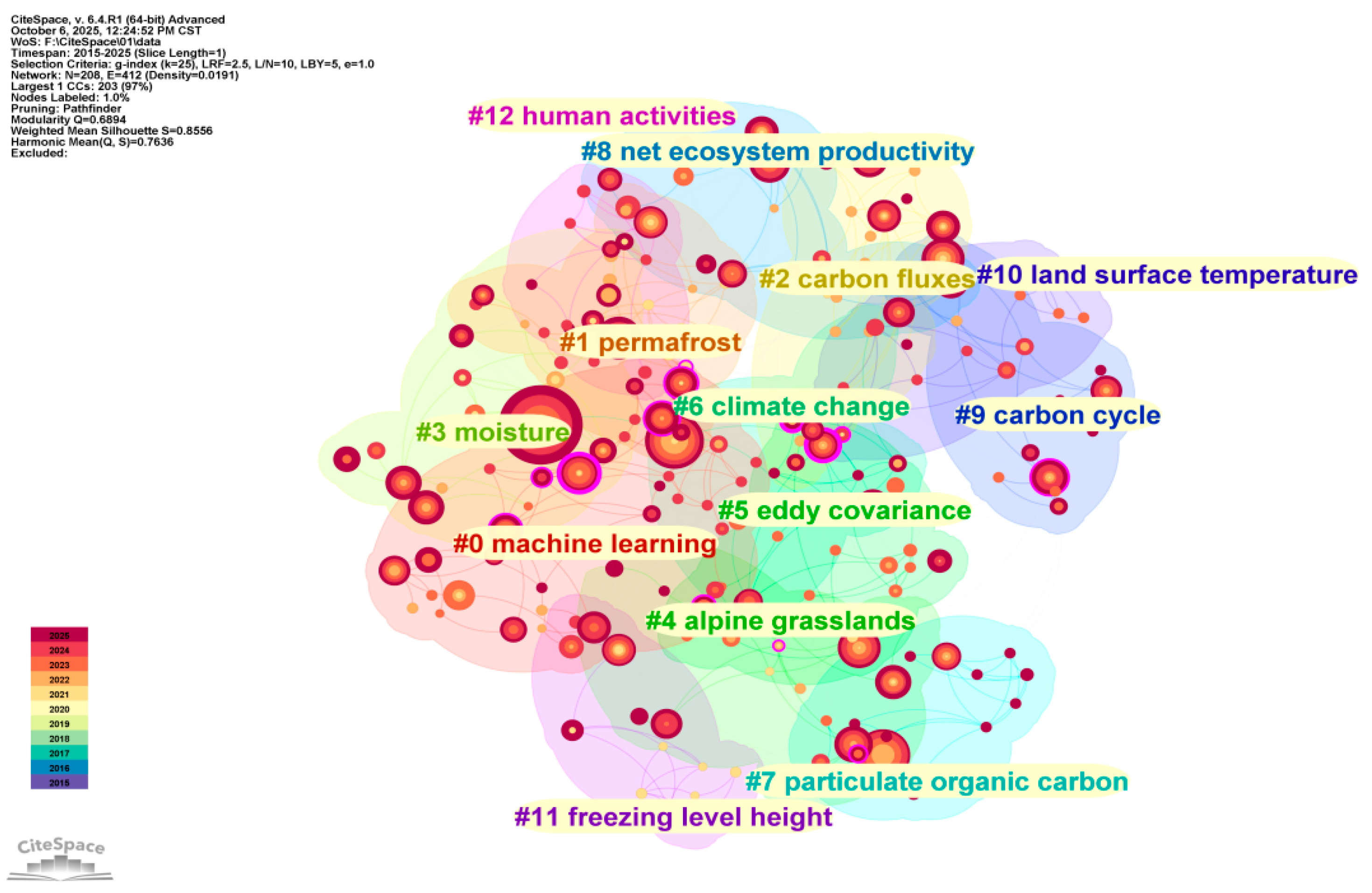

In order to identify the knowledge structure and research topics in this field, we conducted keyword clustering analysis. The clustering results are visualized in

Figure 6 (clustering network diagram) and

Figure 7 (timeline diagram). The detailed information of each clustering module (such as scale and homogeneity) is summarized in

Table 4, aiming to identify research hotspots and knowledge structure. The Q value obtained by analysis is 0.82 (>0.3), indicating that there is a significant clustering structure; the S value is 0.91 (>0.5), indicating that the clustering division is highly consistent (

Figure 6). Through analysis, a total of 13 major research clusters are identified (

Table 4), and the Contour values of all clusters are higher than 0.8, indicating a high degree of consistency within each category [

28,

29,

32,

33].

The results of cluster analysis show that the largest cluster set is # 0 ‘machine learning’ (Contour value 0.804), containing 30 keywords, mainly focusing on the application of artificial intelligence methods in remote sensing inversion of ecosystem carbon flux. Followed by # 1 ‘permafrost’ (Contour value 0.856) and # 2 ‘carbon fluxes’ (Contour value 0.818), which focused on the dynamic monitoring of the carbon cycle and carbon flux in permafrost regions, respectively.

It is worth noting that the # 6 ‘climate change’ cluster has a medium scale (14 keywords), but its betweenness centrality is high, indicating that the topic plays a key role in connecting different research directions. The co-occurrence analysis of high-frequency keywords ‘carbon cycle’ (frequency 13) and ‘eddy covariance’ (frequency 16) revealed that the combination of ecosystem carbon cycle processes and flux observation methods has become the core content of research in this field [

34,

35].

According to the distribution of research topics, these clusters can be summarized into three research directions: (1) method technology frontier, including # 0 ‘machine learning’, # 5 ‘eddy covariance’, etc., focusing on the fusion method of remote sensing data and ground observation; (2) ecosystem processes, including # 2 ‘carbon cycling’, # 4 ‘alpine grasslands’, # 9 ‘carbon cycle’, etc., focusing on the carbon cycle processes of different ecosystems; (3) environmental driving factors, including # 1 ‘permafrost ’, # 3 ‘moisture’, # 6 ‘climate change’, etc., to study the effects of climate and environmental factors on ecosystem respiration.

4.3.2. Analysis of Hot Research Topics

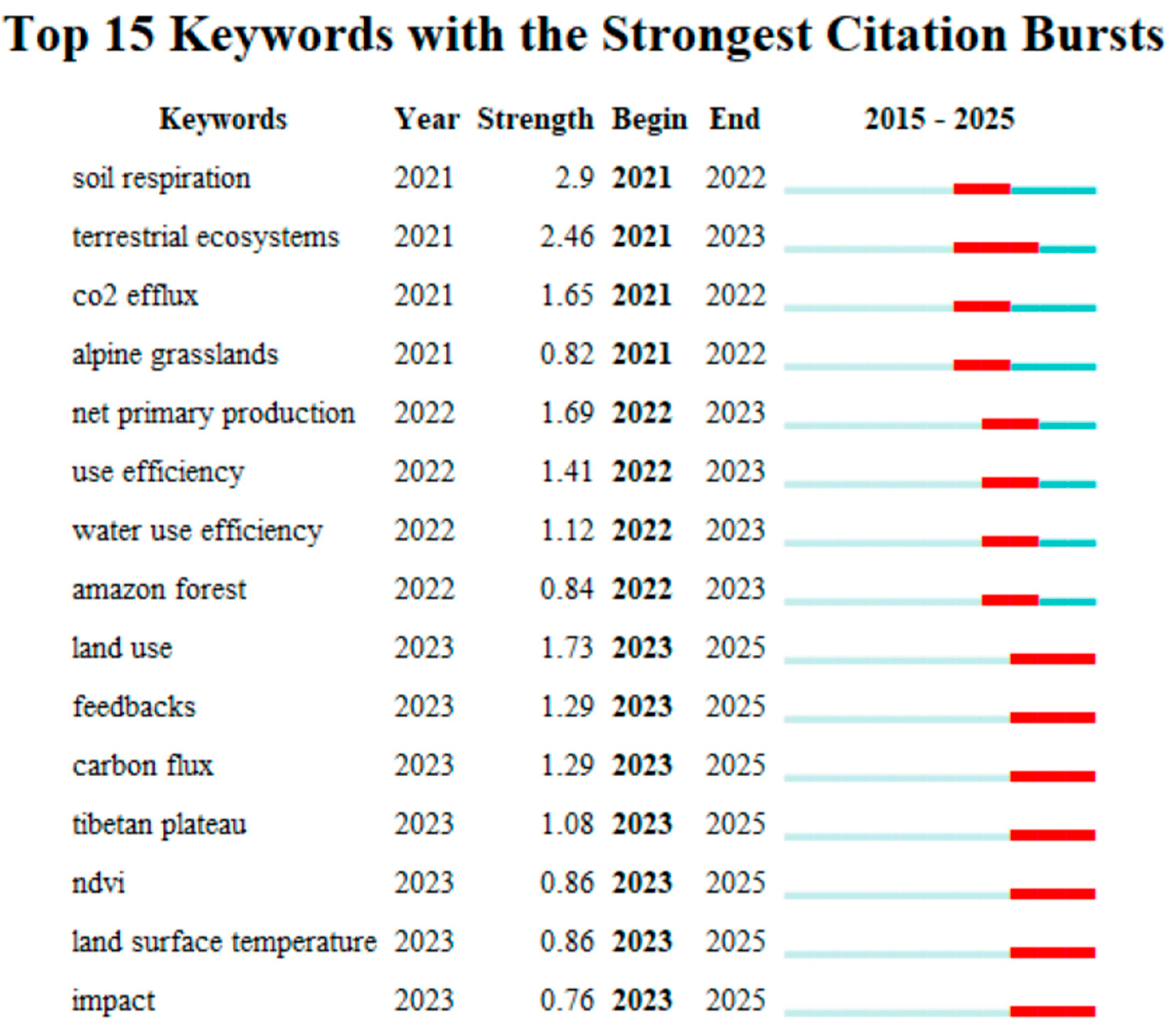

The dynamic evolution of research frontiers and hotspots is identified by burst word detection.

Figure 8 shows the 15 burst words with the highest intensity and their duration, which intuitively reflects the changes of research focus in different periods. The burst word analysis (

Figure 8) shows that ‘soil respiration’ (soil respiration) ranks first with a burst intensity of 2.9 (2021–2022), followed by ‘terrestrial ecosystems’ (terrestrial ecosystems, intensity 2.46) and ‘net primary production’ (net primary productivity, intensity 1.69). Cluster cross-analysis shows that these hot keywords are highly correlated with core clusters such as # 2 ‘carbon fluxes’, # 4 ‘alpine grasslands’ and # 8 ‘net ecosystem productivity’ [

36].

The evolution of research hotspots shows three typical stages and characteristics: (1) The initial stage of research (2021–2022), focusing on the basic carbon flux process and typical ecosystems. Keywords such as ‘soil respiration’, ‘CO

2 efflux’ and ‘alpine grasslands’ were concentrated, reflecting the concern about the mechanism of soil carbon emission and the response of alpine ecosystems in the early stage of the study. (2) The mechanism deepening stage (2022–2023), the research content expands to productivity and efficiency indicators. ‘Net primary production’, ‘use efficiency’ and ‘water use efficiency’ have become emerging hotspots, showing that the research extends from the respiration process to the comprehensive assessment of ecosystem carbon absorption and resource utilization efficiency. (3) The fusion expansion stage (2023–2025), the study further integrates multi-source remote sensing and surface processes. Keywords such as ‘land use’, ‘feedbacks’, ‘carbon flux’, ‘NDVI and ‘land surface temperature’ continue to emerge, indicating that research tends to multi-process coupling of human activity–climate–ecosystem feedback, and the integration of remote sensing indicators (such as NDVI and surface temperature) and carbon flux models has become a frontier direction [

23,

24,

28,

36].

It is particularly noteworthy that the co-occurrence and continuous emergence of keywords such as ‘land use’, ‘feedbacks’ and ‘carbon flux’ reveal the synergistic effect of land use change and climate feedback mechanism in the carbon cycle of agro-ecosystems, marking a new paradigm shift from single process observation to multi-driven and multi-scale comprehensive research.

4.4. Highly Cited Literature Analysis

Through the analysis of

Table 5, we can summarize the three core issues focused on by the highly cited literature.

Flux upscaling and uncertainty assessment: The top-ranked studies (Virkkala et al.) focused on the statistical upscaling of ecosystem CO2 fluxes, which directly responded to the core methodological challenges from site observations to regional/global scale estimates. Its high number of citations highlights the fundamental importance of this topic in this field.

Application of emerging remote sensing drivers: The second-ranked study (Qiu et al.) demonstrated the superiority of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) in monitoring the effects of agricultural drought. This shows that beyond the traditional vegetation index (such as NDVI), exploring new remote sensing data, such as SIF, that can directly reflect the physiological state of vegetation, is the frontier direction to improve the carbon cycle monitoring ability of agricultural ecosystems [

11,

12].

Deeper understanding of key ecosystem processes: The remaining highly cited literature has jointly deepened the understanding of specific processes. This includes the revelation of global carbon flux inconsistency (Jian et al.), the quantification of the contribution of roots to soil respiration (Jian et al.), the offsetting effect of soil respiration on carbon sinks (Watts et al.), the great influence of wildfires and other disturbances on carbon balance (Zhao et al.), and the regulation mechanism of biological and abiotic factors such as nitrogen fertilizer application (Yan et al.), climate warming (Yin et al.) and hydrothermal synergistic drive (Li et al.) on respiration process. These studies constitute the basis for understanding the mechanism of respiration dynamics and climate feedback in agriculture and adjacent ecosystems [

17,

21,

37].

In general, these highly cited papers clearly outline the main line of research in this field. By developing multi-source data fusion and model integration methods (such as upscaling and process models), and using new remote sensing information, including SIF, it aims to more accurately quantify and explain the dynamics of ecosystem respiration and its driving factors in the context of global change.

5. Discussion

Based on the bibliometric analysis of CiteSpace, this study systematically revealed the development trend and knowledge structure evolution of agricultural ecosystem respiration remote sensing research under the context of climate change from 2021 to 2025. It should be noted that the ‘agro-ecosystem’ referred to in this study covers two major types: one is the farmland agro-ecosystem dominated by crop planting (such as farmland, orchard and other artificial management systems), and the other is the grassland agro-ecosystem dominated by herbaceous plants and managed by humans (such as grazing grassland and mowing grassland) [

33]. Although the alpine grassland is close to the native ecosystem in terms of natural attributes, it has become an important part of the grassland agricultural system under the influence of agricultural activities such as grazing and mowing, and is included in the scope of this study [

34,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

As shown in

Figure 1, the research output in this field shows obvious “technology-driven” growth characteristics: the years 2021–2022 is the initial stage, where the average annual number of publications is low but the average citation rate is high, indicating that the research has strong scientific value in the initial stage; from 2023 to 2024, it entered a period of rapid growth, and the annual number of publications increased significantly. The popularization of remote sensing technology and the warming of climate change issues jointly promoted the accumulation of knowledge at this stage. By 2025, the number of publications tends to be stable, but the citation intensity continues to increase, reflecting that the research has entered a stage of deepening integration. It is worth noting that the average citation rate has declined after 2022, which may be related to the lag in citation of new achievements and the differentiation of research quality.

Keyword clustering and burst analysis further reveal the three major evolutionary trends of research topics, and show different characteristics in the two types of agricultural ecosystems:

- (1)

From single-point observation to multi-source fusion, early studies mainly focused on basic carbon flux processes such as ‘soil respiration’ and ‘CO

2 emission’. In the cultivated land ecosystem, the study focused more on the effects of agricultural management measures such as tillage and irrigation on soil respiration [

11,

38,

39,

40,

41]; in the grassland ecosystem, more attention is paid to the regulation of human activities such as grazing intensity and fence management on respiration rate [

41]. Subsequently, the research was extended to comprehensive indicators such as ‘net primary production’ and ‘water use efficiency’, reflecting the development from the respiratory process to a comprehensive assessment of carbon absorption and resource utilization.

- (2)

From method exploration to intelligent inversion, ‘machine learning’ (# 0 clustering) has become the largest research cluster. In the cultivated land ecosystem, machine learning is mostly used to model the relationship between crop residue management and soil respiration. In the grassland ecosystem [

14], it is more focused on the impact assessment of grazing activities on carbon flux. This method forms a ‘model-observation’ closed loop with ‘eddy covariance’ (# 5 clustering), marking an important transformation of the research method.

- (3)

From process analysis to system coupling, keywords such as ‘land use’, ‘feedbacks’, ‘carbon flux’, etc., continue to emerge, indicating that the research tends to multi-process coupling. In the cultivated land ecosystem, pay attention to the synergistic effect of planting system adjustment and climate feedback [

18]; in the grassland ecosystem, the regulation of grazing management on the carbon cycle is emphasized. The collaborative application of remote sensing indicators and carbon flux models is becoming an emerging research paradigm.

It should be noted that the current research is still unbalanced in terms of regions and methods. The study of cultivated land ecosystems is mainly concentrated in typical agricultural areas (such as the Loess Plateau) [

43], while the study of grassland ecosystems is represented by alpine grassland (such as the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau), and the study of tropical agricultural areas and arid areas is relatively weak. In addition, the applicability of machine learning methods in highly heterogeneous agricultural landscapes still needs to be strengthened, especially in grassland ecosystems with diverse management measures and high landscape fragmentation [

34,

44,

45,

46].

5.1. Machine Learning

Cluster analysis showed that ‘machine learning’, as the largest research cluster (Contour value 0.804), contained 30 core keywords, which reflected the key position of artificial intelligence methods in remote sensing research of agricultural ecosystem respiration. Machine learning has become a ‘method engine’ for analyzing the dynamics of ecosystem carbon flux under the context of climate change by virtue of its advantages in dealing with nonlinear relationships, integrating multi-source data and improving inversion accuracy [

17,

47,

48]. The keyword co-occurrence network shows that the clustering mainly focuses on the three dimensions of ‘model algorithm’, ‘feature optimization’ and ‘flux downscaling’, marking the transformation of research methods from traditional statistical regression to a data intelligence-driven paradigm.

In recent years, machine learning has made significant breakthroughs in the methodology of this research field, which is mainly reflected in multi-source data fusion modeling, integrating remote sensing spectral features (such as MODIS-NDVI and Landsat-LST), meteorological driving factors and flux tower observation data to construct a spatio-temporal continuous ecosystem respiration simulation framework [

48,

49]. Algorithm innovation and performance optimization: The application of Random Forest, XGBoost and deep learning network significantly improves the estimation accuracy of respiratory flux, especially under complex underlying surface conditions; its prediction performance is about 20–40% higher than that of traditional models [

48,

49,

50]. Enhancement of cross-scale analysis ability: the method based on machine learning has successfully realized the downscaling calculation of ecosystem respiration from the site scale to the regional scale, which makes up for the deficiency of traditional observation in spatial representation [

38,

44].

Typical case studies show that the strong correlation between ‘machine learning’ clustering and # 2 ‘carbon fluxes’ and # 5 ‘eddy covariance’ reveals key scientific findings: In agricultural ecosystems, machine learning models can effectively capture the synergistic control mechanism of temperature, moisture and vegetation index on respiration process, and the explanatory power (R

2) is generally above 0.7; based on the analysis of feature importance, it was found that ‘land surface temperature’ and ‘moisture’ were the two dominant factors driving respiration variation, especially in arid and semi-arid agricultural areas [

5,

16,

38]. In addition, preliminary progress has been made in the separation of respiratory components (such as autotrophic respiration and heterotrophic respiration) assisted by machine learning, which provides a new way to understand the impact of climate change on soil carbon release [

34,

35,

44,

51].

These methodological advances have important implications for the research in this field: A three-in-one research paradigm of “multi-source data-intelligent algorithm-process mechanism” should be established; it is necessary to pay attention to the interpretability of the model and combine the data-driven results with the ecological mechanism to avoid the “black box” misunderstanding. It is suggested to strengthen the research on the response and prediction of the respiratory process based on machine learning for future climate scenarios [

6,

47,

52]. Preliminary practice shows that the remote sensing inversion framework combined with machine learning has reduced the uncertainty of respiration flux estimation by about 30% in typical agricultural areas.

Future research should focus on solving the following challenges: the extrapolation ability and robustness of machine learning models under extreme climate events (such as drought and heat waves); quantification and embedding of different agricultural management measures (such as irrigation, fertilization) as input characteristics; and how to achieve cross-regional migration and generalization of the model in highly heterogeneous landscapes [

53]. At the same time, the ‘grey box’ model based on the combination of physical mechanism and machine learning will be an important direction to promote the field from correlation analysis to causal inference [

12,

18,

40].

These breakthroughs in machine learning methods have important implications for the formulation of actual climate change mitigation strategies and agricultural policies. High-precision carbon flux inversion mapping based on machine learning can help decision makers accurately identify ‘carbon hotspots’ areas (i.e., areas with high emission intensity) and ‘carbon sink core’ areas in agricultural landscapes, so as to achieve optimal allocation and targeted management of emission reduction resources [

9,

13,

15,

19,

29]. More importantly, such models can quantitatively evaluate the carbon emission reduction benefits and carbon sequestration potential of different agricultural management measures (such as conservation tillage, optimized irrigation, and straw returning), which provides key data support and decision-making basis for establishing a scientific agricultural carbon sink accounting system, designing an ecological compensation mechanism, and formulating differentiated agricultural climate policies. Promoting the deep integration of these intelligent models with agricultural management decision support systems will directly contribute to intelligent and precise low-carbon agricultural practices and serve climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies at the national and global levels [

39,

40,

52,

53].

5.2. Permafrost

Cluster # 1 ‘Permafrost’ (Contour value = 0.856) is the key object to study the effects of climate change on the respiration of alpine grassland agro-ecosystems. It is necessary to clarify that permafrost is mainly distributed in high altitude and high latitude areas, and its influence range is mainly grassland agro-ecosystem (such as natural grazing land, artificial grassland), and basically does not involve typical farming activities in cultivated land agro-ecosystem [

54,

55,

56].

As a huge terrestrial carbon pool, the freeze-thaw process of permafrost directly regulates the stability of soil organic carbon and microbial activity in alpine grassland, which in turn significantly affects the ecosystem respiration dynamics. Studies have shown that the average annual soil respiration flux of grassland ecosystems in typical permafrost regions such as the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is 200–400 g C·m

−2·yr

−1, and the fluctuation range of respiration rate during seasonal freezing and thawing is more than 30% [

11,

57,

58]. The grassland ecosystem respiration in the permafrost degradation area increased by 15–25%, which significantly changed the regional carbon balance pattern [

38,

46,

59].

The respiration process in permafrost regions is driven by multiple factors: natural factors include permafrost thickness, ground temperature and vegetation type; man-made and climate forcing mainly include grazing activities, grassland reclamation and global warming. Different from the respiration-driven mechanism dominated by agricultural measures such as tillage and irrigation in the cultivated land ecosystem, the respiration process of the alpine grassland ecosystem is more susceptible to the synergistic regulation of freeze-thaw cycles and grazing management [

21,

23]. Freeze-thaw alternation significantly enhances the mineralization rate of organic matter by changing soil structure, water content and microbial community, especially in the spring thaw period [

49,

56]. This feature is particularly evident in the artificially managed grassland agricultural system [

44,

46,

59].

Current research still has limitations, such as sparse observation sites, insufficient temporal resolution of remote sensing, and insufficient analysis of carbon-climate feedback mechanisms. In particular, it still faces challenges in distinguishing grassland agricultural systems from natural tundra ecosystems. In the future, it is necessary to integrate multi-platform remote sensing, in-situ sensors and process models to construct a respiration monitoring system of ‘frozen soil–vegetation–climate’ co-evolution, and focus on analyzing the role of agricultural activities such as grazing management in the carbon cycle of frozen soil, so as to provide scientific basis for the adaptation strategy and carbon management of alpine grassland agro-ecosystem [

45,

46,

59].

5.3. Carbon Fluxes

Carbon flux (Cluster # 2) is one of the core indicators for assessing the impact of climate change on agro-ecosystem respiration (Contour = 0.818,

Table 4 and

Figure 5). As a key quantitative parameter of the ecosystem carbon cycle, carbon flux directly reflects the intensity of CO

2 exchange between the agricultural ecosystem and the atmosphere, especially in typical areas such as crop rotation areas and alpine agro-pastoral ecotones [

17,

56,

57,

60]. Its dynamic changes are closely related to the global carbon balance and the climate feedback mechanism. The results show that the annual net carbon exchange of typical agro-ecosystems can reach −600 to −800 g C·m

−2·yr

−1 (negative value represents carbon sink), while in the non-growing season dominated by respiration, the carbon emission flux can reach 5–8 μmol·m

−2·s

−1 [

47,

61,

62]. Through the joint observation of eddy covariance technology and remote sensing inversion, it was found that the implementation of conservation tillage measures reduced the respiration rate of the farmland ecosystem by 15–25%, and significantly enhanced the net carbon sink function of the system [

34,

61].

The spatial and temporal variation of carbon flux was driven by multiple factors: natural factors such as temperature increase (Q

10 = 1.5–2.5) and precipitation pattern change, and human intervention included irrigation management, straw returning and cropping system adjustment. Mechanism studies have shown that soil moisture can explain 40–60% of the carbon flux variation by regulating microbial activity and root growth [

8,

9,

17,

18,

19]. The covariation of vegetation index (such as NDVI) and total primary productivity dominated the seasonal dynamics of carbon uptake [

59,

63]. There are still three limitations in the current research: Most of the observations are focused on a single ecosystem, and there is a lack of a comprehensive assessment of the agricultural landscape scale; the observation space of traditional stations is not representative enough, and the applicability of the remote sensing inversion algorithm in heterogeneous farmland needs to be improved. The separation and mechanism analysis of carbon flux components (autotrophic/heterotrophic respiration) are not sufficient. In the future, it is necessary to integrate multi-source remote sensing data, flux observation network and process model to construct a carbon flux monitoring and simulation framework of ‘drive–process–flux’ integration, so as to provide a scientific basis for carbon management and climate adaptation of agro-ecosystems.

5.4. Moisture

Moisture (Cluster # 3) is one of the key environmental factors for assessing the impact of climate change on agro-ecosystem respiration (Contour value = 0.817,

Table 4 and

Figure 5). As a decisive control parameter of the soil respiration process, water conditions directly regulate microbial activity and root physiological processes, especially in typical systems such as dry farming areas and rain-fed farmlands [

64]. Its dynamic changes are closely related to soil carbon emission intensity and carbon cycle mode. Studies have shown that when the soil volumetric water content is 15–25%, the respiration rate of the agricultural ecosystem reaches a peak; under extreme drought (35%) conditions, the respiration rate decreased by 40–60% and 20–30%. Through long-term monitoring, it was found that optimized irrigation measures could reduce the seasonal variation of soil respiration by 25–35%, while maintaining the carbon absorption function of crops [

65,

66].

The regulation of water on the respiration process is affected by multiple factors: natural factors include precipitation pattern, soil texture and groundwater depth, and human intervention involves irrigation systems and coverage measures. The mechanism study showed that water regulated the ratio of aerobic/anaerobic respiration by changing soil pore connectivity and oxygen diffusion rate [

60,

63]. At the same time, the mineralization pathway of organic carbon was changed by affecting substrate diffusion and microbial community structure [

64]. There are three limitations in the current research: Most observations are limited to a single soil layer, and there is a lack of systematic monitoring of the water transport-respiration coupling process in the profile; the traditional point measurement is difficult to capture the spatial heterogeneity of field water, and the accuracy of remote sensing inversion of soil moisture in vegetation coverage period still needs to be improved. The analysis of the threshold effect of water-temperature co-driven respiration is insufficient. In the future, it is necessary to integrate multi-source remote sensing, soil sensor network and ecological process model to construct a water–carbon flux coupling monitoring system of ‘atmosphere–soil–vegetation’ continuum, so as to provide theoretical support for accurate prediction and water management of agricultural carbon emissions under climate change [

66].

5.5. Alpine Grasslands

Alpine grassland (Cluster # 4) is a typical area for studying the effects of climate change on grassland agro-ecosystem respiration (Contour value = 0.852,

Table 4 and

Figure 5). It needs to be clarified that alpine grassland belongs to the category of grassland agricultural ecosystem, and its management mode is mainly grazing and mowing, which is essentially different from the cultivated land agricultural ecosystem with crop planting as the core in structure, function and human intervention.

As an important carbon pool in high altitude areas, the ecosystem respiration process of alpine grassland is highly sensitive to climate change. Studies have shown that the soil respiration rate of alpine grassland during the growing season is usually between 1.5–3.2 μmol CO

2·m

−2·s

−1, and there will be obvious respiration pulses during the freeze-thaw alternation period, and the single-day flux can reach 1.5–2 times the average level of the growing season [

67,

68]. Through long-term positioning observation, it was found that enclosure measures, as a typical grassland management method, reduced the total ecosystem respiration of degraded alpine grassland by 20–30%, and improved soil carbon sequestration capacity [

57,

60,

69]. This mode of regulating carbon flux through management measures is in stark contrast to the mechanism of affecting respiration through tillage, irrigation, etc., in cultivated agricultural ecosystems [

64,

70].

The spatial differentiation of the respiration process in alpine grassland is controlled by both natural and human factors. Natural factors include permafrost distribution, altitude gradient and vegetation type. Human disturbance is mainly reflected in grazing activities and grassland reclamation, which is significantly different from the respiratory driving mechanism dominated by agricultural management measures such as fertilization, irrigation and crop rotation in the cultivated agricultural ecosystem [

33,

64,

71]. The mechanism study showed that freeze-thaw cycles significantly stimulated microbial activity by destroying soil aggregate structure and releasing soluble organic carbon. Grazing pressure indirectly affects soil temperature and humidity by changing vegetation coverage and soil compactness, thereby regulating respiration intensity. These processes highlight the uniqueness and complexity of grassland agro-ecosystems in response to climate change [

67,

68,

71].

There are three shortcomings in the current research: Most of the observations are concentrated in the growing season, and the continuous monitoring of the non-growing season, especially the critical period of freezing and thawing, is insufficient; traditional quadrat survey is difficult to capture the spatial heterogeneity of alpine grassland, and remote sensing technology has limited accuracy in distinguishing alpine grassland types and degradation levels. The understanding of the climate feedback mechanism of the alpine grassland carbon cycle process is still not deep, especially the lack of comparative studies with cultivated agricultural ecosystems. In the future, it is necessary to establish a comprehensive observation network of space–ground integration, develop remote sensing inversion algorithms suitable for alpine grassland, couple ecological process models with climate change scenarios, and construct a carbon cycle prediction and early warning system for alpine grassland, so as to provide scientific and technological support for grassland agricultural ecosystems to adapt to climate change.

5.6. Eddy Covariance

The eddy covariance (Cluster # 5) is one of the key technologies to study the effects of climate change on the respiration of the farmland ecosystem (Contour = 0.871,

Table 4 and

Figure 5). As the gold standard for ecosystem carbon flux observation, this method provides key in situ data for understanding the response of the farmland ecosystem carbon cycle to climate change by directly measuring the CO

2 exchange flux between the atmosphere and the surface [

71]. Studies have shown that the net carbon exchange flux of the farmland ecosystem shows significant diurnal and seasonal dynamics. The carbon absorption flux during the growing season can reach −10 to −15 μmol CO

2·m

−2·s

−1, while the night respiration flux is 2–5 μmol CO

2·m

−2·s

−1 [

34,

64]. Long-term observations have further confirmed that conservation tillage, as a typical farmland management method, can reduce nighttime respiration flux by 15–25%, and significantly enhance the net carbon sink function of the system [

67].

The application effect of the eddy covariance technique is affected by multiple factors: Environmental factors include atmospheric stability, wind speed and underlying surface uniformity; technical factors involve instrument accuracy and data quality control process [

72]. Methodologically, by simultaneously measuring the covariance of vertical wind speed and CO

2 concentration, this technique can achieve non-interference continuous monitoring of ecosystem respiration [

73]; its combination with remote sensing data has further promoted the expansion of observation scale from stations to regions [

34,

61,

67,

72,

74].

However, there are still three limitations in the current research: Most flux stations are distributed on flat and uniform farmland underlying surface, and the applicability of observation in complex terrain areas is insufficient; the problem of flux underestimation under weak nighttime turbulence has not been completely solved. The separation of autotrophic and heterotrophic components in ecosystem respiration is still highly dependent on auxiliary observation and model estimation. Future research should focus on optimizing flux observation schemes in complex environments, developing data quality control methods based on artificial intelligence, and strengthening multi-scale data fusion and model assimilation to build a more complete carbon flux monitoring system for farmland ecosystems, and provide technical support for accurately assessing agricultural carbon budget and formulating emission reduction strategies.

5.7. Climate Change

Climate change (Cluster # 6) is one of the core factors driving the respiration process of agro-ecosystems (Contour value = 0.851,

Table 3 and

Figure 5). As a key environmental stress factor affecting the carbon cycle, climate change significantly regulates the respiration intensity and dynamic pattern of agricultural ecosystems through the direct and indirect effects of temperature, precipitation and CO

2 concentration [

75]. The results showed that for every 1 °C increase in temperature, the agricultural soil respiration rate increased by about 10–20% on average [

15,

20,

23,

76]; the change of precipitation pattern can make the interannual variation of respiration flux reach 25–40% [

77]. Through the analysis of long-term observation data, it is found that climate warming has led to an increase of 15–30% in the total ecosystem respiration in the growing season of major agricultural areas in China, which has significantly changed the regional carbon balance [

75,

77].

The effects of climate change on root respiration are complex and diverse: elevated temperature directly enhances microbial activity and enzyme reaction rate, precipitation changes regulate substrate diffusion by changing soil water availability, and elevated CO

2 concentration indirectly affects root respiration by promoting plant growth [

75,

78]. Studies have shown that water availability is the main limiting factor for respiration in arid and semi-arid agricultural areas. In irrigated agricultural areas, temperature is the dominant control factor [

75,

77,

78]. There are three limitations in current research: Most studies focus on the independent effects of a single climate factor, and the comprehensive evaluation of multi-factor interactions is insufficient; observations based on site scale are difficult to fully reflect regional heterogeneity, and the combination of remote sensing and models still needs to be strengthened. There is limited understanding of the impact of extreme climate events (such as drought and heat waves) on respiratory processes in the context of climate change. In the future, it is necessary to construct a multi-scale and multi-process comprehensive research framework, develop an integrated model system coupled with climate-ecology-remote sensing, deepen the understanding of the climate feedback mechanism of agricultural ecosystem respiration, and provide a scientific basis for agricultural carbon management to cope with climate change [

50,

57,

69,

79,

80].

5.8. Particulate Organic Carbon

Cluster analysis showed that particulate organic carbon (Cluster # 7) was one of the important indicators for assessing the carbon cycle process of agro-ecosystems (Contour value = 0.888,

Table 3 and

Figure 5). As the most active component of the soil carbon pool, particulate organic carbon directly reflects the turnover dynamics of organic matter, especially in agricultural soils with frequent tillage disturbances. Its content change is closely related to soil respiration intensity and carbon balance [

61,

73]. Studies have shown that the content of particulate organic carbon in typical farmland ecosystems is usually between 0.8–1.5 g/kg, accounting for about 30–50% of total soil organic carbon, and its mineralization rate can reach 0.5–1.2% per day, which is an important carbon source for soil respiration [

18,

37,

41,

42,

58]. Through long-term positioning experiments, it was found that the implementation of straw returning measures increased the storage of particulate organic carbon in topsoil by 25–40%, while reducing its turnover rate [

81].

The spatial differentiation of particulate organic carbon is driven by multiple factors: natural factors include soil texture, temperature conditions and water status, and human intervention is mainly reflected in tillage methods, organic material input and rotation system. The microscopic mechanism study showed that tillage accelerated the physical exposure of particulate organic carbon and microbial decomposition by destroying the structure of soil aggregates. Organic fertilizer application promotes the formation and stability of particulate organic carbon by providing fresh substrates [

81,

82]. There are three limitations in the current research: Most studies focus on topsoil (0–20 cm), and a lack of understanding of the dynamics of particulate organic carbon in deep soil; traditional chemical analysis methods are difficult to distinguish the sources and components of particulate organic carbon, and the application of emerging technologies, such as nuclear magnetic resonance, is not yet universal. The quantitative relationship between particulate organic carbon turnover and greenhouse gas emissions is not deep enough. In the future, it is necessary to combine stable isotope tracing, spectral remote sensing and process models to construct a complete monitoring system of particulate organic carbon ‘formation-transformation-emission’, so as to provide a theoretical basis for agricultural soil carbon sequestration and carbon emission regulation.

5.9. Limitations and Prospects

This study has several limitations, primarily related to the time span of the data. Since the literature search ended in September 2025, it did not cover the entire year of 2025. This may result in insufficient capture of the latest research trends for that year. Additionally, the relatively short research period of five years (2021–2025) may limit our ability to accurately assess the long-term impact of some emerging frontier topics, such as “grey box model” and “pulse emission”.

However, it should be emphasized that these limitations reflect the dynamic nature of the research field. Although the analysis period is relatively limited, this study systematically reviews the evolution of key developmental stages in this area. It provides an important benchmark for understanding the current status and trends in remote sensing research on agricultural ecosystem respiration under climate change. More importantly, this field is currently in a phase of rapid development. With growing attention to global climate change and continuous advances in remote sensing technology, related research is expected to attract more attention and achieve significant breakthroughs.

Future research should focus on the following directions: Deepening the understanding of multi-process coupling mechanisms: Future work should aim to develop an integrated “climate–soil–vegetation–management” model. This requires combining multi-platform remote sensing data with flux observation networks [

13,

68,

75]. A key goal is to analyze response thresholds and lag effects of respiration processes to extreme climate events, such as droughts and heatwaves. Intelligent method innovation: It is necessary to develop a “grey box” model that integrates physical mechanisms and machine learning. This will improve the model’s generalization ability and mechanistic interpretability across heterogeneous agricultural landscapes [

48,

50]. Evaluation of management effectiveness: Strengthening the assessment of management impacts is crucial [

40,

51,

53]. Long-term observation and remote sensing verification systems should be established to evaluate how agricultural management practices—such as conservation tillage and optimized irrigation—affect ecosystem respiration. The ultimate aim is to accurately quantify the carbon reduction potential and comprehensive ecological benefits of these practices [

53].

We recommend building a three-part technical framework of “remote sensing monitoring–model simulation–decision support.” Based on bibliometric analysis, priority areas—such as alpine agricultural zones and dry farmland—should be identified, and an integrated sky–ground observation network deployed. Using multi-source data assimilation and AI algorithms can enhance real-time inversion and prediction of respiratory fluxes. Combined with climate scenarios and policy objectives, an agricultural carbon assessment and regulation system should be established. This will provide a scientific basis and technical support for agricultural carbon management within the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and help advance the field from mechanistic analysis toward intelligent control.

6. Conclusions

Based on the bibliometric analysis of CiteSpace, this study systematically revealed the development law and frontier dynamics of agricultural ecosystem respiration remote sensing research under the background of climate change from 2021 to 2025. It should be noted that the ‘agro-ecosystem’ referred to in this study covers two major types: one is the farmland agro-ecosystem dominated by crop planting (such as farmland, orchard and other artificial management systems), and the other is the grassland agro-ecosystem dominated by herbaceous plants and managed by humans (such as grazing grassland and mowing grassland) [

33]. Although the alpine grassland is close to the native ecosystem in natural attributes, it has become an important part of the grassland agricultural ecosystem under the influence of agricultural activities such as grazing and mowing, so it is included in the scope of this study.

The study found that the field presents a significant ‘technology-driven-interdisciplinary-global collaboration’ triple helix development characteristic. Driven by the progress of remote sensing technology and the warming of climate change issues, the annual number of papers has increased rapidly from a low level in 2021 to a stable and high yield in 2025. The research hotspots have gradually expanded from the initial observation of the soil respiration process to the frontier directions such as machine learning inversion, alpine system response and multi-process coupling. It is worth noting that these research directions have different emphases in the two types of ecosystems: cultivated land ecosystem research pays more attention to the regulation of respiration by conservation tillage, irrigation and other measures, while grassland ecosystem research pays more attention to the carbon cycle effects of grazing management, enclosure and other activities. The scientific research institutions with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the United States Department of Energy and NASA as the core have formed a global cooperation network led by China and the United States and connected by European nodes, which constitutes a multi-polar collaborative research system.

The research reveals three key evolution trends: At the methodological level, the intelligent transformation from traditional remote sensing inversion to the deep fusion of machine learning and vorticity covariance is realized; in the content dimension, a systematic cognitive framework from single respiration flux monitoring to multi-process coupling of ‘climate-soil-vegetation-human activities’ was formed. This framework is reflected in the collaborative analysis of cropping system and climate feedback in the cultivated land ecosystem, and in the grassland ecosystem, where it is reflected in the interaction between grazing pressure and freeze-thaw process. In terms of technology integration, the regional scale expansion from site observation to multi-platform remote sensing collaboration was completed. Typical cases show that the machine learning model improves the accuracy of respiratory flux inversion by about 20–40%. At the same time, farmland management measures such as conservation tillage and optimized irrigation significantly reduced the farmland respiration rate by 15–30%. This reduction is mainly achieved by reducing soil disturbance, maintaining soil moisture and improving soil structure, thereby inhibiting the mineralization of soil organic matter and regulating microbial activity. Similarly, grassland management measures such as enclosure and grazing prohibition have reduced the total respiration of alpine grassland by 20–30%. These measures play a role by promoting vegetation restoration, increasing soil carbon input through litter and root exudates, and reducing soil compaction caused by livestock, thereby creating conditions that are not conducive to rapid decomposition. These findings highlight the important role of intelligent methods and differentiated agricultural management in carbon emission reduction.

In the future, this study proposes four priority development directions: First, an integrated respiration monitoring network of ‘sky and land’ should be constructed. While strengthening the observation of tropical agricultural areas and arid areas, a differentiated monitoring index system for the cultivated land ecosystem and the grassland ecosystem should be established, respectively. Secondly, the ‘grey box’ model of development mechanism and data fusion is developed to improve the generalization ability of the model in a heterogeneous landscape according to the differences in driving mechanisms and management modes between cultivated land and grassland. Thirdly, a real-time inversion of respiration flux and carbon sink assessment system based on multi-source data assimilation and AI algorithm is established, focusing on the development of carbon sink assessment methods that can serve both cultivated land and grassland management; finally, it is necessary to promote the standardization and sharing of remote sensing data, flux observation and ecological models, especially to strengthen the data comparability and method versatility among different types of agricultural ecosystems.

By constructing a closed-loop research framework of ‘monitoring–simulation–management’, the research results can provide data support and method basis for differentiated carbon management and climate change adaptation strategy formulation of cultivated land and grassland agro-ecosystem, promote the field from mechanism analysis to intelligent regulation, and provide a scientific path for achieving green low-carbon agriculture and sustainable development goals (SDG13 climate action, SDG15 terrestrial ecology).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M.; methodology, X.M. and T.C.; validation, T.C. and J.L.; formal analysis, K.S., F.Z. and T.C.; resources, J.L. and T.C.; data curation, X.M.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and T.C.; visualization, F.Z. and J.H.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Startup Funds for Introduced Talents, Shanxi Agricultural University, grant number 2024BQ16”, “The national natural science foundation of China, grant number 42507452” and “Socio-economic Influencing Factors of Soil Erosion in Huangshui River Basin and Its Control Measures, grant number 23Q061”. The APC was funded by 2024BQ16”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Hauck, J.; Pongratz, J.; Pickers, P.A.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 2141–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Corbeels, M.; Demenois, J.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A.; Fallot, A.; Feder, F.; Cardinael, R. A global meta-analysis of soil organic carbon in the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kumar, B.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Amarjyothi, K.; Sutar, A.K.; Roy, S.; Rao, S.A.; Nanjundiah, R.S. Machine learning in Earth system science: A survey of recent advances and future directions. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 245, 104557. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel, D.; Pavlick, R.; Fisher, J.B.; Asner, G.P.; Saatchi, S.; Townsend, P.; Miller, C.; Frankenberg, C.; Hibbard, K.; Cox, P. Observing terrestrial ecosystems and the carbon cycle from space. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1762–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, E.; Müller, C.; Parisse, B.; Napoli, R.; Zhang, J.-B.; Rezanezhad, F.; Van Cappellen, P.; Moser, G.; Jansen-Willems, A.B.; Yang, W.H.; et al. A global dataset of gross nitrogen transformation rates across terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R.; Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Reeves, M.; Hashimoto, H. A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production. Biosciences 2004, 54, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Luca, A.D.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, A., Pirani, S.L., Connors, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. Available online: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/101846/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Neelam, M.; Hain, C.R. Part 1: Disruption of the Water-Carbon Cycle under Wet Climate Extremes. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Moran, R.; Al-Yaari, A.; Mialon, A.; Mahmoodi, A.; Al Bitar, A.; De Lannoy, G.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, N.; Lopez-Baeza, E.; Kerr, Y.; Wigneron, J.-P. SMOS-IC: An Alternative SMOS Soil Moisture and Vegetation Optical Depth Product. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.S.; Randerson, J.T.; Field, C.B.; Matson, P.A.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Klooster, S.A. Terrestrial ecosystem production: A process model based on global satellite and surface data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1993, 7, 811–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Y. UAVs as remote sensing platforms in plant ecology: Review of applications and challenges. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 14, 1003–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lyu, G.; Wei, J.; Yang, H.; Piao, S. Progress and challenges in remotely sensed terrestrial carbon fluxes. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Reichstein, M.; Margolis, H.A.; Cescatti, A.; Richardson, A.D.; Arain, M.A.; Arneth, A.; Bernhofer, C.; Bonal, D.; Chen, J.; et al. Global patterns of land-atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat, and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2011, 116, G3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Liang, S.; Wang, D.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, J.; Yao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Y. Advances in Methodology and Generation of All-Weather Land Surface Temperature Products From Polar-Orbiting and Geostationary Satellites: A comprehensive review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag 2024, 12, 218–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Baste, I.; Larigauderie, A.; Leadley, P.; Pascual, U.; Baptiste, B.; Demissew, S.; Dziba, L.; Erpul, G.; Fazel, A.; et al. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; pp. 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Teske, S.; Nagrath, K. Global sector-specific Scope 1, 2, and 3 analyses for setting net-zero targets: Agriculture, forestry, and processing harvested products. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.F.; Prentice, I.C.; Canadell, J.G.; Williams, C.A.; Wang, H.; Raupach, M.; Collatz, G.J. Recent pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 due to enhanced terrestrial carbon uptake. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for kee the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciais, P.; Reichstein, M.; Viovy, N.; Granier, A.; Ogée, J.; Allard, V.; Aubinet, M.; Buchmann, N.; Bernhofer, C.; Carrara, A.; et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 2005, 437, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming our world: Implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37 (Suppl. S1), 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]