Research on Grassland Classification Method in Water Conservation Areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Data processing: utilize machine learning methods to fuse multi-source heterogeneous grassland data and accurately characterize grassland information;

- (2)

- Indicator screening: apply machine learning algorithms such as XGBoost to rigorously select features from high-dimensional datasets and establish a comprehensive and objective set of classification indicators;

- (3)

- Evaluation model: train and systematically compare the performance of multiple machine learning algorithms in grassland classification, with quantitative validation using metrics including overall accuracy, weighted F1-score, and AUC;

- (4)

- Result validation: quantitatively compare the final classification results with official grassland classification outcomes to assess consistency and discrepancies, thereby clarifying the potential and applicability of the proposed method for operational use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. Evaluation Index Screening

2.4.2. Construction of the Evaluation Model

- Spatial block cross-validation and Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique

- Histogram Gradient Boosting

- Initialization:

- 2.

- Iterative Tree Construction:

- 3.

- Obtain the Final Model:

- Light Gradient Boosting Machine

- Random Forest

- Hyperparameter Optimization and Accuracy Validation

3. Results

3.1. Image Fusion Results

3.2. Results of Indicator Screening

3.3. Grassland Class Evaluation

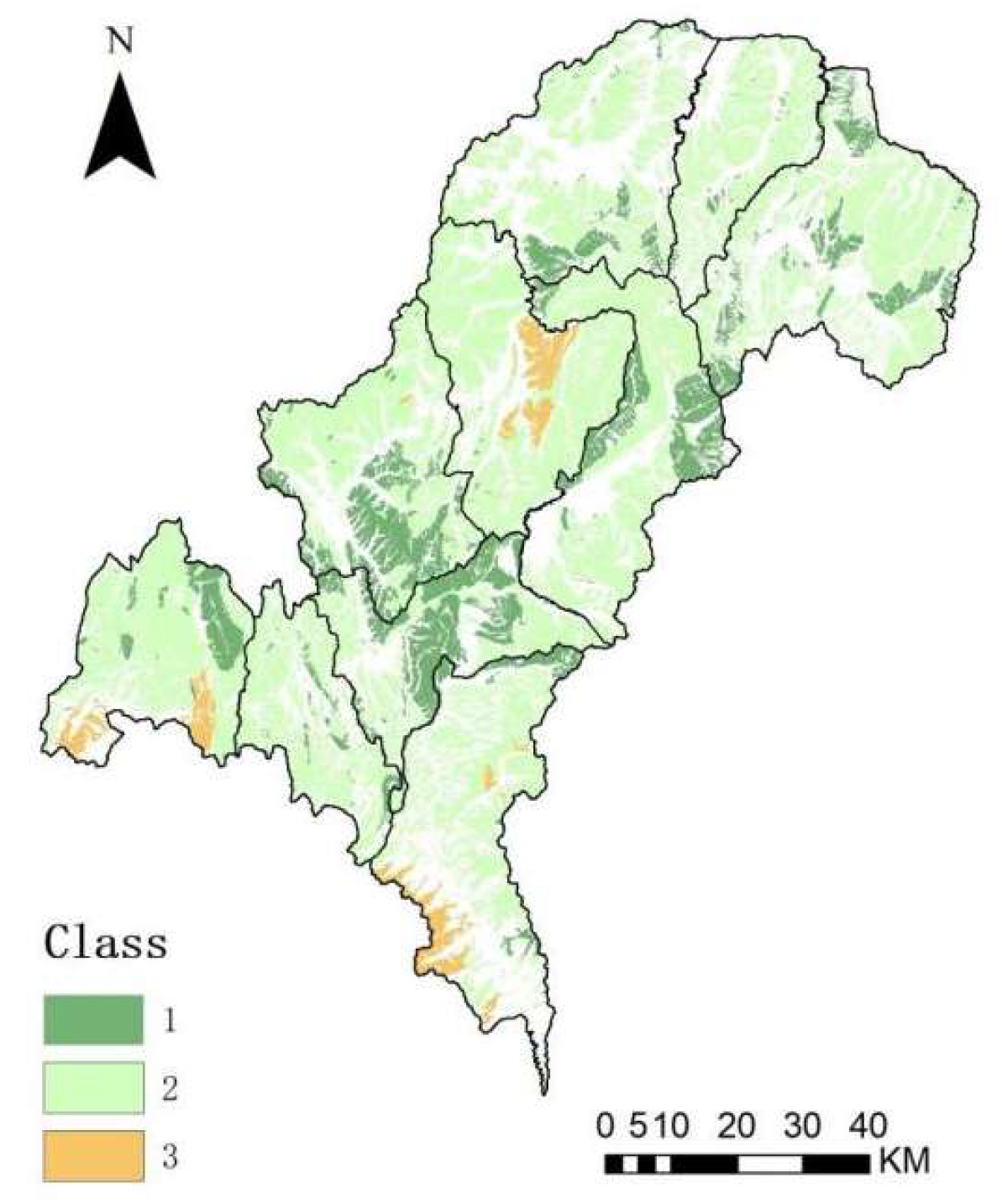

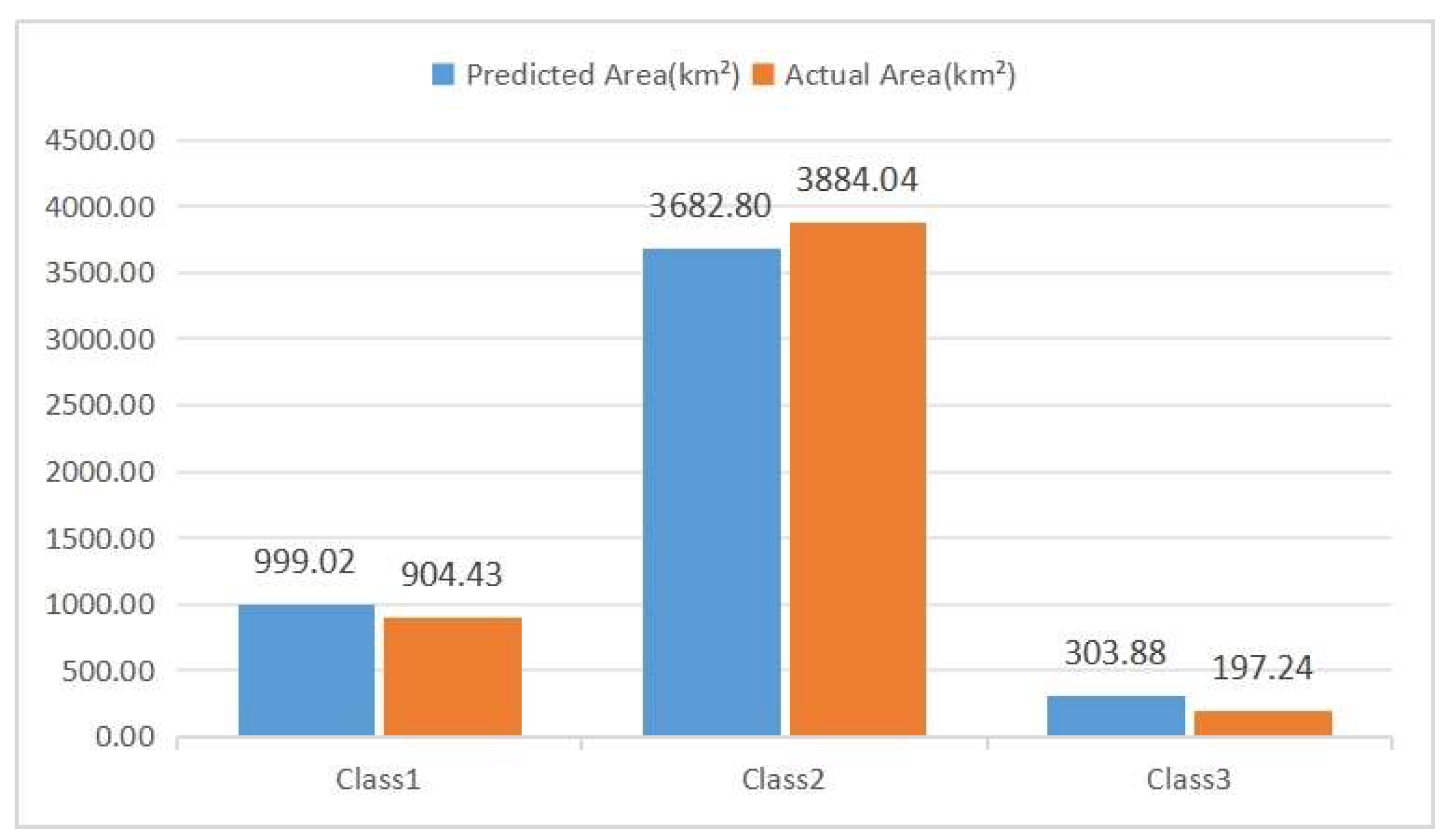

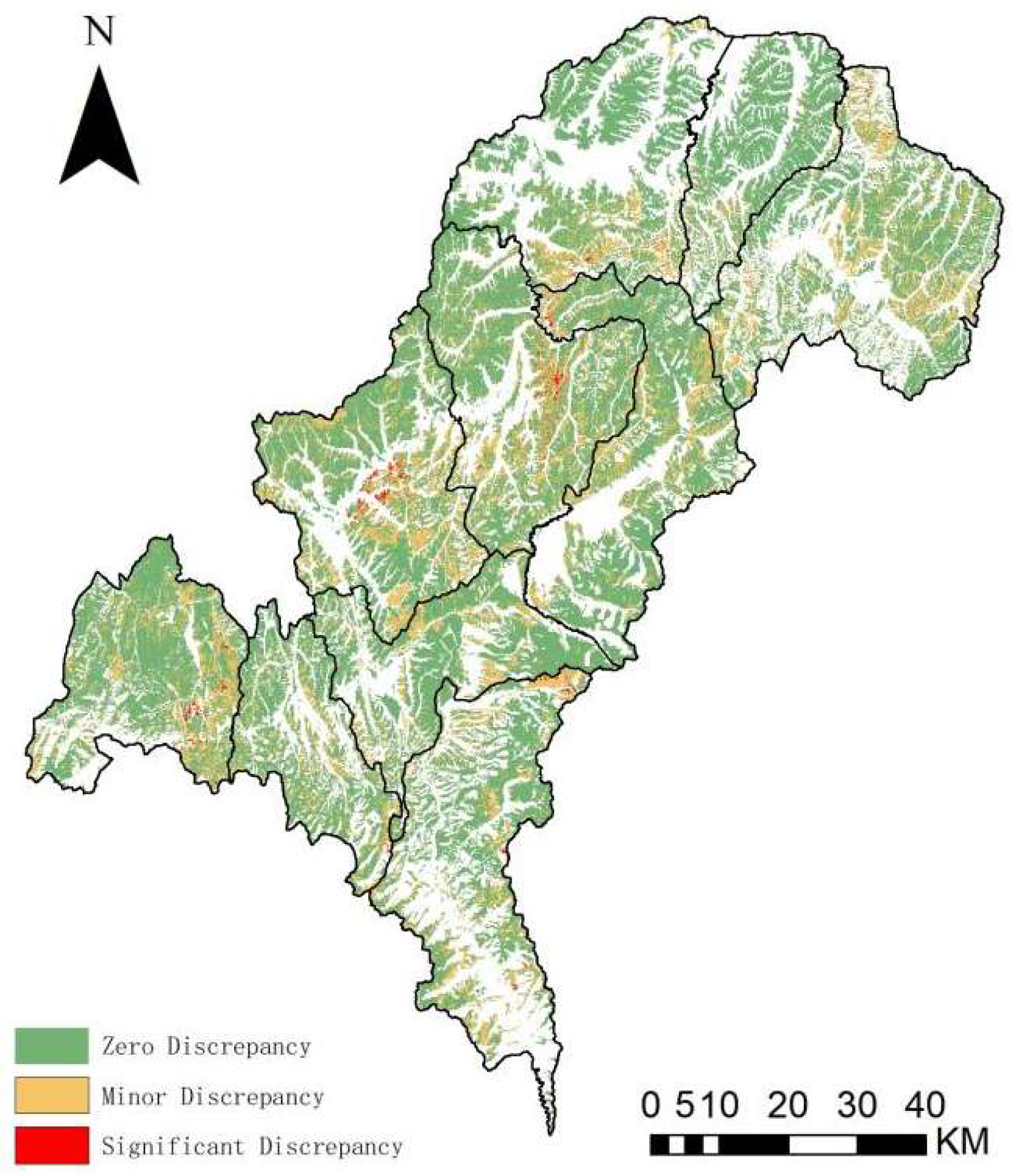

3.4. Validation of Evaluation Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Regarding data processing, a CNN-based deep learning model was employed to fuse Landsat panchromatic and multispectral images, producing a 15 m high-resolution temporal dataset. Quantitative evaluation demonstrated that the fusion quality achieved a 74.13% reduction in RMSE (to 0.0524) and a 29.57% increase in PSNR compared to the GS fusion method. This approach effectively mitigated the mixed-pixel issue in medium-resolution remote sensing over plateau regions, providing a reliable data foundation for accurate inversion of vegetation parameters such as FVC.

- (2)

- In terms of indicator screening, this study applied XGBoost combined with collinearity analysis (VIF < 5) to quantitatively identify hydrothermal conditions (MAP and AT) as the dominant drivers of alpine grassland class differentiation. Aspect, functioning as an energy regulator, demonstrated greater importance than most soil and vegetation indicators. This finding enhances our understanding insight into the formation mechanisms of alpine grassland ecosystems.

- (3)

- A systematic comparison demonstrated that XGBoost achieved optimal classification performance, with an overall accuracy of 0.829. A pixel-by-pixel absolute difference analysis between the predicted and actual grassland classes revealed perfect agreement in 75.82% of the area, minor discrepancies in 23.63%, and major discrepancies in only 0.54%. Grasslands of class 2 were dominant (71.67%), while Class 1 and Class 3 grasslands were mainly distributed in river valleys with favorable hydrothermal conditions and in alpine or urban areas subject to human disturbance or harsh natural conditions, respectively.

- (4)

- This framework provides an objective and efficient monitoring approach for administrative departments, including strict protection for high-quality grasslands (Class 1), carrying capacity-based grazing for widespread grasslands (Class 2), and precision restoration for degraded grasslands (Class 3), for instance, planting drought-resistant species on south-facing slopes. By closely linking grassland conditions with dominant climatic factors, this method offers a replicable scientific tool for establishing dynamic early-warning systems and adaptive management strategies in response to future climate change.

- (5)

- Future research efforts should focus on the following directions: applying the framework to multi-year time-series data to dynamically monitor grassland responses to climate change and human activities; integrating SAR data to compensate for optical remote sensing gaps during cloudy and rainy seasons in the plateau; and conducting independent validation and transferability studies in adjacent counties to enhance model generalization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, G.D.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lu, C.X.; Xie, G.D.; Zhang, Y.L.; Lu, C.X.; Zheng, D.; Cheng, S.K. Service value of natural grassland ecosystems in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2001, 1, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Hou, L.; Kang, N.; Nan, Z.; Huang, J. A meta-regression analysis of the economic value of grassland ecosystem services in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.H.; Liu, G.H.; He, J.S. Research Status and Development Trends of Grassland Protection Technologies: A Literature Analysis. Pratacultural Sci. 2020, 37, 703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Bullock, J.M.; Lavorel, S.; Manning, P.; Schaffner, U.; Ostle, N.; Chomel, M.; Durigan, G.; Fry, E.L.; Johnson, D.; et al. Combatting global grassland degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.D.; Lu, C.X.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, D. Valuation of alpine grassland ecosystem services on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2003, 21, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.D. Investigation of Water-Ecology-Human Activities Reveals the Imbalance of the Asian Water Tower and Its Potential Risks. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 2761–2762. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B.J.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Shi, P.; Fan, J.; Wang, X.D.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, W.W.; Wu, F. Current Condition and Protection Strategies of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Security Barrier. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2021, 36, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Xue, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, R.; Zeng, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Grassland changes and adaptive management on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, S.; Sternberg, M.; Argaman, E.; Henkin, Z.; Dovrat, G.; Zaady, E.; Paz-Kagan, T. Testing a novel pasture quality index using remote sensing tools in semiarid and Mediterranean grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 357, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaix, C.; Alard, D.; Chabrerie, O.; Diquélou, S.; Dutoit, T.; Fontès, H.; Lemauviel-Lavenant, S.; Loucougaray, G.; Michelot-Antalik, A.; Bonis, A. Plant evenness improves forage mineral content in semi-natural grasslands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 387, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Gang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; An, R.; Wang, K.; Odeh, I.; et al. Quantitative assess the driving forces on the grassland degradation in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, in China. Ecol. Inform. 2016, 33, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jia, L.; Cai, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, T.; Huang, A.; Fan, D. Assessment of Grassland Degradation on the Tibetan Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachendorf, M.; Fricke, T.; Möckel, T. Remote sensing as a tool to assess botanical composition, structure, quantity and quality of temperate grasslands. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, T.; Batelaan, O.; Duan, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M. Spatiotemporal fusion of multi-source remote sensing data for estimating aboveground biomass of grassland. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Q.; Huang, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y. Remote Sensing Monitoring of Grasslands Based on Adaptive Feature Fusion with Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.L.; Zheng, J.H.; Mu, C. Quality Assessment of Grassland Net Primary Productivity Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 1690–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Vörös, M.; Somodi, I.; Csákvári, E.; Reis, B.P.; Sáradi, N.; Török, K.; Halassy, M. Towards harmonised monitoring of grassland restoration: A review of ecological indicators used in the temperate region. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 230, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Yu, X. Seasonal variation in carbon flux and the driving mechanisms in the grassland ecosystem in a mountain region of Northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Feilhauer, H.; Kühn, I.; Doktor, D. Mapping land-use intensity of grasslands in Germany with machine learning and Sentinel-2 time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 277, 112888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Estimation of grassland biomass using machine learning methods: A case study of grassland in Qilian Mountains. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 8953–8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.F.; Dong, K.H. Comprehensive Evaluation of Vegetation Utilization in Subalpine Meadows. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2002, 2, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, J.T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Li, K.; Li, C. Research on multi-classification method of grassland category based on semi-supervised clustering and clustering. In Proceedings of the SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering, San Diego, CA, USA, 21–25 August 2022; Volume 12348, pp. 945–953. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Wen, G.; Lu, J.; Yang, H.; Jin, Y.; Nie, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y. Machine learning in soil nutrient dynamics of alpine grasslands. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.K.; Wen, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.Y. Soil-Quality Effects of Grassland Degradation and Restoration on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Dong, S.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhi, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Resilience of revegetated grassland for restoring severely degraded alpine meadows is driven by plant and soil quality along recovery time: A case study from the Three-river Headwater Area of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 279, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yang, H.; Huang, L.; Chen, C.; Lin, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, J. Grassland degradation remote sensing monitoring and driving factors quantitative assessment in China from 1982 to 2010. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.S.; Holden, N.M. Indices for quantitative evaluation of soil quality under grassland management. Geoderma 2014, 230, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coops, N.C.; Bolton, D.K.; Hobi, M.L.; Radeloff, V.C. Untangling multiple species richness hypothesis globally using remote sensing habitat indices. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubry, I.; Doan, T.; Chu, T.; Guo, X. A Systematic Review on the Integration of Remote Sensing and GIS to Forest and Grassland Ecosystem Health Attributes, Indicators, and Measures. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3262. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Gan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Z. Impacts of building configurations on urban stormwater management at a block scale using XGBoost. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T. Integrating explainable AI and causal inference to unveil regional air quality drivers in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z. Water Erosion Risk Assessment and Predictive Modelling for Cultural Heritage under Climate Change: A Case Study of the Great Wall in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 510, 145645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Peng, H.; Xu, L.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Z.; Chen, W. Probabilistic evaluation of cultural soil heritage hazards in China from extremely imbalanced site investigation data using SMOTE-Gaussian process classification. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 67, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhat-Duc, H.; Van-Duc, T. Comparison of histogram-based gradient boosting classification machine, random Forest, and deep convolutional neural network for pavement raveling severity classification. Autom. Constr. 2023, 148, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Sheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Using Machine Learning Algorithms Based on GF-6 and Google Earth Engine to Predict and Map the Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Matter Content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Mo, X.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Lv, C. Attributing the changes of grass growth, water consumed and water use efficiency over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.L.; Liu, X.W.; Duo, Y. Effects of daily variation of hydro-thermal factors on alpine grassland productivity on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 3719–3728. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.W.; Liu, H.; Hu, P.; Peng, H.; Wang, S. Multi-factor Impact Analysis of Grassland Phenology Changes on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau Based on Interpretable Machine Learning. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 3375–3388. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Luo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wei, Y.; Xiao, L.; Deng, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, W. Simulating the spatiotemporal variations in aboveground biomass in Inner Mongolian grasslands under environmental changes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Category | Subcategory Data | Content | Sensor | Acquisition Time | Resolution | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground-based measured data | Vegetation cover | Plot coverage values | July 2022 | Quadrat scale (1 m × 1 m) | Self-collected by the research group | |

| Edible forage yield | Dry weight per quadrat (g/m2) | July 2022 | Quadrat scale (1 m × 1 m) | Self-collected by the research group | ||

| Remote sensing image data | Landsat 8 | Multispectral imagery(B1–7) | OLI | July 2022 | 30 m | http://glovis.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 1 July 2024.) |

| Panchromatic band | July 2022 | 15 m | ||||

| MOD15A2 | FPAR data | MODIS | 2022 | 500 m | https://earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 1 July 2024.) | |

| ALOS DEM | Digital Elevation Model | PALSAR L | 2006–2011 | 12.5 m | https://search.asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 7 Jue 2024.) | |

| Meteorological Data | Air Temperature | Mean annual temperature, >0 °C accumulated temperature | 2002–2022 | Station scale | http://www.geodata.cn (accessed on 1 July 2024.) | |

| Precipitation | Mean annual precipitation | 2002–2022 | Station scale | |||

| Soil Data | Soil Chemical Properties | Soil organic matter, Soil texture, Total nitrogen, Total phosphorus, Total potassium, pH | 2009–2019 | 90 m/1 km | The High-Resolution National Soil Information Grid of China, a dataset published by the Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (ISSAS). | |

| Soil Physical Properties | surface soil gravel content | 2009–2019 | 1 km |

| Factors | Full Name of Indicator | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Climate | Mean Annual Temperature | MAT |

| Mean Annual Precipitation | MAP | |

| >0 °C Accumulated Temperature | AT | |

| Topography | Slope | SLOPE |

| Aspect | ASPECT | |

| Elevation | ELEV | |

| Soil | Soil Thickness | TKN |

| Soil Organic Matter | SOM | |

| Soil Texture | ST | |

| surface soil gravel content | GSC | |

| potential of Hydrogen | pH | |

| Total Potassium | TK | |

| Total Nitrogen | TN | |

| Total Phosphorus | TP | |

| Soil Bulk Density | BD | |

| Vegetation | Vegetation Coverage | FVC |

| Edible Forage Yield | EFY | |

| cumulative annual productivity | DHIcum | |

| annual minimum productivity | DHImin | |

| seasonal variation in productivity | DHIsea |

| Model | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | CNN | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.0524 |

| GS | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.2026 | |

| PSNR | CNN | 27.43 | 26.7 | 32.7 | 30.12 | 43.41 | 40.63 | 35.91 | 25.73 |

| GS | 22.16 | 21.52 | 27.66 | 24.7 | 37.09 | 35.22 | 30.4 | 19.86 |

| Variable | Standardized Coefficients | t-Statistic | Sig | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | −0.231 | −7.095 | 0.000 | 0.166 | 6.007 |

| AT | −0.113 | −5.639 | 0.000 | 0.438 | 2.281 |

| TK | −0.058 | −2.915 | 0.004 | 0.443 | 2.260 |

| EFY | 0.099 | 6.458 | 0.000 | 0.754 | 1.327 |

| PH | −0.076 | −3.420 | 0.001 | 0.355 | 2.817 |

| ASPECT | 0.058 | 4.303 | 0.000 | 0.979 | 1.021 |

| SOM | 0.084 | 2.502 | 0.012 | 0.155 | 6.443 |

| BD | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.976 | 0.157 | 6.382 |

| ELEV | 0.262 | 7.452 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 7.021 |

| TN | −0.203 | −5.649 | 0.000 | 0.136 | 7.340 |

| DHIcum | 0.022 | 1.156 | 0.248 | 0.508 | 1.967 |

| DHIsea | −0.012 | −0.703 | 0.482 | 0.563 | 1.776 |

| GSC | −0.142 | −7.674 | 0.000 | 0.516 | 1.938 |

| SLOPE | −0.088 | −5.225 | 0.000 | 0.619 | 1.615 |

| TP | 0.054 | 3.308 | 0.001 | 0.666 | 1.501 |

| Variable | Standardized Coefficients | t-Statistic | Sig | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | −0.111 | −4.148 | 0 | 0.248 | 4.025 |

| GDD | −0.126 | −6.49 | 0 | 0.474 | 2.108 |

| TK | −0.011 | −0.616 | 0.538 | 0.581 | 1.722 |

| EFY | 0.081 | 5.31 | 0 | 0.773 | 1.293 |

| PH | −0.148 | −7.142 | 0 | 0.418 | 2.392 |

| ASPECT | 0.063 | 4.633 | 0 | 0.983 | 1.018 |

| SOM | −0.037 | −1.806 | 0.071 | 0.434 | 2.304 |

| DHIcum | 0.007 | 0.365 | 0.715 | 0.516 | 1.936 |

| DHIsea | 0 | 0.009 | 0.993 | 0.604 | 1.655 |

| GSC | −0.147 | −7.929 | 0 | 0.522 | 1.915 |

| TP | 0.021 | 1.302 | 0.193 | 0.721 | 1.387 |

| SLOPE | −0.056 | −3.599 | 0 | 0.737 | 1.357 |

| Model | learning_rate | max_depth | n_estimators | max_iter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.3 | 6 | 100 | |

| HistGradientBoosting | 0.3 | 6 | 100 | |

| LightGBM | 0.3 | 6 | 100 | |

| RandomForest | 6 | 100 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | Weighted F1-Score | F1-Score Class1 | F1-Score Class2 | F1-Score Class3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.829 | 0.818 | 0.829 | 0.820 | 0.567 | 0.896 | 0.512 |

| HistGradientBoosting | 0.812 | 0.799 | 0.812 | 0.803 | 0.524 | 0.885 | 0.504 |

| LightGBM | 0.826 | 0.814 | 0.826 | 0.818 | 0.568 | 0.894 | 0.496 |

| RandomForest | 0.644 | 0.763 | 0.645 | 0.679 | 0.465 | 0.746 | 0.359 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, K.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Zou, R.; Zhao, L.; Yang, F.; Wen, T. Research on Grassland Classification Method in Water Conservation Areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data Fusion. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232503

Yan K, Hu Y, Wang L, Huang X, Zou R, Zhao L, Yang F, Wen T. Research on Grassland Classification Method in Water Conservation Areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data Fusion. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232503

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Kexin, Yueming Hu, Lu Wang, Xiaoyan Huang, Runyan Zou, Liangjun Zhao, Fan Yang, and Taibin Wen. 2025. "Research on Grassland Classification Method in Water Conservation Areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data Fusion" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232503

APA StyleYan, K., Hu, Y., Wang, L., Huang, X., Zou, R., Zhao, L., Yang, F., & Wen, T. (2025). Research on Grassland Classification Method in Water Conservation Areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data Fusion. Agriculture, 15(23), 2503. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232503