1. Introduction

Public policy decisions reshape economic outcomes by reallocating resources and altering incentives. Their effects propagate not only through direct transfers and regulations but also via indirect channels—sectoral linkages, behavioral responses, and general-equilibrium spillovers. Classic incidence and general-equilibrium analyses show how policy burdens and benefits shift across factors and sectors, while modern network and aggregation results highlight how input–output structures transmit shocks and policies across the economy in non-trivial ways [

1].

A large body of ex-ante and ex-post evaluations shows that CAP payments affect agricultural production and income through both direct transfer mechanisms and indirect market and structural channels. Ex-ante simulation tools (partial equilibrium and CGE) consistently find that changes in Pillar-I envelopes alter sectoral output, factor use, and income, with effects differing across commodities and regions [

2,

3]. Complementary econometric and accounting-based assessments confirm that direct payments represent a sizeable share of sectoral income and that their incidence is heterogeneous across EU Member States and farm types [

4,

5]. Importantly, livestock sectors often exhibit stronger relative exposure to horizontal income support and to voluntary coupled schemes, reflecting their higher dependency on policy transfers and the targeted nature of coupled measures [

6,

7]. These findings motivate the need for transparent, sector-by-sector incidence maps that can be used alongside CGE or econometric tools to diagnose where policy leverage is strongest and to guide the design of Strategic Plan allocations.

Within European agriculture, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) combines broadly targeted decoupled income support with more narrowly targeted coupled measures, yielding heterogeneous incidence across livestock sectors and potential spillovers [

7,

8]. Recent peer-reviewed work documents redistributive and incidence patterns of CAP payments and highlights how allocation criteria and instrument design shape who benefits and by how much across farm types and sectors [

9,

10]. The 2023–2027 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) deploys a diverse set of sectoral actions whose incidence across livestock differs because envelopes, eligibility rules, and potential spillovers vary by instrument, including non-horizontal measures such as investment aid that affect farm performance and structural adjustment [

11]. Comparisons are further complicated by scale effects and by the coexistence of broadly targeted income support and narrowly targeted coupled measures [

12]. For policy and evaluation to be informative, support must be expressed in a way that is comparable across sectors and time, and that cleanly distinguishes direct channels from indirect ones. We quantify how selected CAP sectoral interventions translate into relative support across livestock sectors when normalized by final output and assess the stability of these conclusions under plausible allocation uncertainty, reporting interpretable influence coefficients for milk, pigs, beef, and poultry in 2024 and 2028. Our contribution is a compact, deterministic matrix framework that maps actions to sectors, separates direct from indirect channels, and reports interpretable influence coefficients for four main sectors. The approach is inspired by IO/SAM accounting logic and by quasi-matrix policy-impact mapping traditions reviewed in

Section 2 [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

This study has three aims. First, we quantify the direct and indirect exposure of four major Polish livestock sectors to selected CAP interventions in 2024 and 2028. Second, we test the robustness of sectoral exposure rankings to plausible uncertainty in the allocation of horizontal income support. Third, we propose a compact, replicable matrix map linking intervention envelopes to sectoral final output, separating direct from spillover effects.

The approach proposed in this article can help identify these effects and impacts. However, anticipating the direct and indirect effects of such interventions on economic–production outcomes in individual markets and between markets, and ultimately on aggregate agricultural production, is difficult. This article does not set the ambitious research goal of comprehensively examining the impact of all sectoral interventions on the economic–production outcomes of agriculture as a whole. A preliminary step is taken, however, by examining selected interventions for several sectors, showing their direct and indirect effects.

The results presented may be useful not only for practical applications but also as a contribution to further research in this area. The message of the article is thus methodological–applicative. The problem addressed concerns the influence of the institutional–regulatory sphere on real processes, here narrowed to assessing the impact of certain market-intervention measures on final production in selected agricultural sectors.

2. Matrix-Based Approach to Analyzing Intervention Effects in Agriculture—Literature References

The specific approach presented here—using matrix calculus to assess how intervention instruments translate into production outcomes in selected agricultural sectors—has very few direct counterparts in the literature. Matrix methods in economics originate in Leontief’s inter-industry flow framework and remain among the most widely used analytical tools [

13]. In the IO tradition, technical coefficients describe how outputs of one sector require inputs from others, so a policy impulse generates a direct effect in the targeted sector and indirect effects in connected sectors through inter-industry linkages. These channels are commonly summarized by IO multipliers that quantify how an initial shock propagates through production networks [

14,

18]. Our framework is therefore IO-inspired accounting: instead of estimating full multipliers, we provide a compact incidence map that separates dedicated (diagonal) from spillover (off-diagonal) exposure. Input–output matrices (and their more comprehensive SAM variants [

19] encode technical production coefficients that link inputs to outputs across sectors, allowing researchers to trace direct and indirect effects as well as the propagation of output or cost shocks through the economy [

13,

14,

16]. They have also been employed for structural comparisons across countries and time, and are routinely tied to national accounts to ensure measurement consistency [

14,

15]. This IO logic supports policy simulations, identification of sectors with the strongest linkages, and provides the accounting backbone for CGE and integrated IO-econometric models used in macroeconomic applications, including in the Polish literature [

14,

15,

17].

The input–output matrix has of course been used to analyze linkages within agriculture or, more broadly, within the agri-food sector. There is a large literature in this area. However, it concerns analysis of input–output (technical–production) linkages in agriculture and the agri-food sector—for example, changes in input intensity or productivity [

20,

21]. Such an approach, in relation to the agri-food economy, appears in the Polish literature in Mrówczyńska-Kamińska [

22], Bear-Nawrocka & Mrówczyńska-Kamińska [

23,

24], Czyżewski & Grzelak [

25,

26], Ambroziak [

27], as well as Czyżewski [

28]. Related matrix-based studies include the use of IO tables to identify sectoral clusters and internal/external linkages [

29], EU Agricultural Input–Output Tables that disaggregate agri-food activities to measure food-chain connections and feed GTAP/CGE models [

20], and SAM-based multiplier analyses of food-support programs such as SNAP [

21].

Input–output analysis has also been widely applied to agricultural policy evaluation, including CAP direct payments and rural-development/structural-fund measures. These studies use IO/SAM multipliers to trace how support affects production and income via direct and indirect channels, and they document heterogeneous incidence across agricultural branches. Examples include CAP multiplier and incidence assessments at regional and national levels [

30,

31], evaluations of CAP and structural-fund impacts in Mediterranean agriculture with IO methods [

32], and later applications quantifying direct and spillover effects of CAP instruments across farming branches [

33,

34]. Our contribution relates to this tradition but differs in scope: we do not model full inter-industry propagation, focusing instead on a transparent action-by-sector incidence map under minimal data requirements.

Policy interventions in agriculture affect sectoral performance through several well-established incidence channels. Transfers can relax income and liquidity constraints, reduce risk exposure, and influence investment, input use, and structural adjustment, thereby translating into production and market outcomes at the sector level [

35,

36]. Because these channels operate in sectors of very different economic scale, comparing nominal envelopes across markets can be misleading: the same budgetary transfer may imply substantial leverage in a small sector and only marginal relevance in a large one. A standard way to express policy incidence in comparable terms is therefore to relate support to sector size, proxied by final output. Normalizing intervention allocations by final output yields dimensionless “support intensity” coefficients that are comparable across sectors and time, consistent with the gross transfer-to-output logic used in agricultural policy accounting such as the Producer and Consumer Support Estimates [

37,

38]. This conceptual framing motivates our matrix mapping of intervention envelopes into direct (dedicated) and indirect (spillover) sectoral exposure.

As mentioned, the literature on using matrices to quantify the incidence of policy instruments on economic outcomes is still scarce, particularly with respect to separating direct and indirect effects in specific agricultural markets. Existing contributions are mostly ideational or semi-quantitative: Wieliczko [

39] and EU evaluation documents [

40] rely on descriptive quasi-matrix layouts with plus/minus scoring to indicate expected impacts, while Monke and Pearson [

41] use table-based quasi-matrices combining signs and qualitative judgments. Our approach is closest to the quasi-matrix tradition of Esposti and Sotte [

42] and the European Commission guidelines [

43], which organize interventions (rows) against sectoral effects (columns) along the inputs → outputs → results → impacts logic, allowing either qualitative entries (−, 0, +, ++, +++) or numerical values depending on data availability. We extend this line by providing a fully numerical, deterministic matrix incidence map that enables transparent ranking of interventions and identification of dedicated versus spillover effects under minimal data requirements.

3. Materials and Methods

The article analyzes nine CSP intervention actions and their incidence in four livestock markets (milk, pigs, beef, poultry). We selected these actions because they represent the dominant share of livestock-relevant CAP envelopes in Poland, have explicit sectoral allocation keys or eligibility rules that allow consistent empirical mapping, and jointly illustrate horizontal income support alongside targeted coupled and investment measures (

Table 1). The set is illustrative rather than exhaustive, providing a tractable subset to demonstrate the matrix framework before extending it to the full CAP portfolio.

Empirical inputs come from two public sources. First, intervention envelopes and sectoral allocation keys for the nine actions are taken from the Polish CAP Strategic Plan (CSP) 2023–2027. These data provide action-level budgets and eligibility/allocation rules used to populate the action-by-sector transfer matrix . Second, sectoral final output for milk, pigs, beef, and poultry is obtained from Statistics Poland and Eurostat national accounts/agricultural statistics. The analysis covers Poland and uses two cross-sections—2024 and 2028—representing the initial and final years of the CSP programming horizon. All monetary values are expressed in thousand euros and aligned to the respective year’s CSP and output accounts. Based on these inputs, matrix records action-by-sector transfer values, matrix normalizes matrix by sectoral final output to obtain incidence coefficients, and we refer to the same incidence map as when interpreting diagonal entries as dedicated (direct) effects and off-diagonals as spillovers (indirect effects).

The starting point—the first stage—of the study is the concept of a matrix of direct and indirect linkages between intervention actions and agricultural markets, namely:

—denotes the value of transfers from intervention action allocated to sector , and each row sum equals the CSP envelope of action (budget constraint ). Thus, provides a balanced action-by-sector map of planned CAP transfers for a given year.

Such a layout allows a preliminary mapping of intervention actions to the sectors targeted by these interventions within budget constraints. It is mainly of balancing significance—it allows examination of the consistency of the financial constraint with the planned allocation of funds in the individual actions to the selected sectors. By construction, the total CSP envelope equals the sum of all action–sector transfers, . We also define matrix as the row-normalized version of , where , capturing sector shares within each action.

The second stage of the study is to determine the share of a given intervention action (its value as defined in the previous matrix) in the value of production (or sales) of a given sector. This makes it possible to examine the direct and indirect effects of intervention actions on selected sectors. To some extent, this is analogous to the Producer Support Estimate (PSE)—the annual gross monetary value of transfers from consumers and taxpayers to agricultural producers [

45]; or Consumer Support Estimate (CSE)—the annual gross monetary value of transfers to (from) consumers of agricultural commodities [

45]. The matrix layout can be as follows:

Effects of intervention actions on sectors:

where

—final output (revenue proxy) of the sector j included in the analysis from 1 to m, denotes final output of sub-market within sector ; is the value of transfers from intervention action allocated to sector (from Equation (1)); is the incidence coefficient of action in sector , i.e., transfers from action expressed as a share of sector ’s final output; is the total relative influence of action across the considered sectors (row sum of ).

This matrix formulation—where variables are the shares of a given action (monetary) in final production (monetary)—can serve as the basis for assessing the impact of the analyzed actions on the sectors under study, which is the aim of the analysis. These coefficients, by construction, refer to the traditional input–output matrix—technical/economic coefficients, i.e., the input (service) of the

j-th product to produce one unit of the

i-th output (service), i.e., the dependence of

i-sector output on j-sector output, interpreted as the impact of j-output on

i-output. Taken together, they form the input–output matrix [

3,

24,

25]. This formulation also allows examination of changes in the shares of intervention actions in sectors over time (Δ), as shown in Equation (3). The interpretation is identical to Equation (2), but concerns changes.

Changes in coefficients of intervention impacts on sectors:

Based on the above matrices, it is possible to determine the direct and indirect effects of intervention actions on specific agricultural markets (sectors). Direct and indirect effects are obtained directly from the incidence coefficients in Equation (2). Diagonal entries of represent dedicated (direct) effects of action on its primary sector , whereas off-diagonal entries capture spillovers (indirect effects) to other sectors. For clarity, we denote this direct-plus-spillover incidence map as in Equation (4) and use its row and column sums to compute total action- and sector-level exposure.

Direct and indirect effects of intervention actions on sectors:

where

—the incidence coefficient of intervention action in sector , i.e., the value of transfers from action allocated to sector expressed as a share of sector ’s final output; diagonal elements represent dedicated (direct) effects of actions targeted to their primary sectors; off-diagonal elements for capture spillovers (indirect effects) of action on other sectors; is the total exposure of sector to all analyzed actions (column sum: direct + spillover effects); is the total cross-sector influence of action across the considered sectors (row sum).

Changes over time (Δ) are computed as cross-sectional differences between year-specific matrices (2028 minus 2024). Thus, Δ compares two static incidence maps and does not represent within-year dynamics.

Direct and indirect effects of intervention actions changes:

Equations (2)–(5) yield descriptive incidence coefficients separating dedicated (direct) from spillover (indirect) exposure. Empirically, we populate from CSP envelopes and allocation keys (2024, 2028), normalize by sectoral final output to obtain , and interpret diagonal vs. off-diagonal entries as direct vs. spillover effects (). Robustness is assessed by a budget-neutral ±10% reweighting of sectoral shares in I 1 and I 2. The coefficients are deterministic support-to-output ratios, not statistical or causal estimates.

4. Results

All figures reported below are deterministic ratios derived from published envelopes and sectoral final output; no standard errors or

p-values are implied by the framework. Using the empirical inputs described in

Section 3 (Data), we populate the action-by-sector transfer matrices for 2024 and 2028 and report the resulting incidence coefficients below.

4.1. Empirical Estimates of the Matrices of Intervention Values Across Sectors and Constraints

The values in Equations (6) and (7) for the budget constraint and the value of intervention actions by sector are estimates based on actual CSP data (Equations (6) and (7) were derived from Equation (1) by narrowing the scope to the analyzed number of sectors and the intervention actions considered). This is a balancing perspective and shows the scale of intervention values allocated to the agricultural markets (sectors) included in the study. One can see the dominance of Instrument I 1 (Basic income support) and the largest inflow of funds to the milk market (sector). We do not assess this, as the article takes a positive, not normative, economics perspective. This caveat also applies to subsequent inferences.

The value of intervention activities in sectors in thousands of euros in year 2024:

The value of intervention activities in sectors in thousands of euros in year 2028:

Based on Equations (6) and (7), changes in the value of intervention support across the analyzed sectors were computed (Equation (8)). One can observe some stabilization and even a decline in support in the period considered.

Changes In The value of intervention activities in sectors in thousands of euros in years 2024–2028:

Because the values in Equations (6)–(8) are in absolute terms, they are not suitable for comparative assessments, including the core aim—assessing the direct and indirect effect of a given action on a given sector. To enable this, the values were normalized to comparable magnitudes (percentages). The subsequent matrices, starting with Equation (9), present these normalized figures.

4.2. Empirical Estimates of the Share of Actions Within Sectors and Assessment

Equations (9) and (10) show the share of a given intervention action in the total value of actions within a sector. These calculations, used to determine the role of a given intervention action in the sum (relative to others) within a sector, are based on the quantities from Equation (1). Equation (9) is obtained by dividing each cell of

by the column sum of

. For each sector

, we compute the share of action

in the total interventions received by that sector as

where

Thus, each column of

sums to 100%.

The share of specific intervention actions in the total value of interventions planned for a given sector (in %) in the year 2024:

The share of specific intervention actions in the total value of interventions planned for a given sector (in %) in year 2028

The figures in Equations (9) and (10), analyzed by columns, allow an approximate assessment of how a given intervention action affects a given sector (and enable some ranking) in terms of economic–production outcomes. One may also assume they reflect, to some extent, CAP makers’ intentions regarding the selection of interventions. In this sense they indicate the ranking of actions with respect to agricultural markets. In other words, they depict the potential impact of a given action—relative to other CAP interventions—on a given agricultural market (sector) as embedded in the CSP. The key observation is the dominance of the first two actions, I 1 and I 2. These two are thus assigned the greatest importance in the CSP. Apart from the milk sector and, to some extent, the beef sector, which also receive dedicated actions I 5.1 and I 5.2, these two (essentially income transfers) almost fully substitute for the impact of the other actions considered. The remaining actions contribute only marginally relative to I 1–I 2 in this normalization, which suggests a limited incidence of these instruments on the four sectors considered. The resulting intervention pattern is consistent with the CSP design that prioritizes horizontal income support supplemented by dedicated ruminant measures. Horizontal income actions provide broad income transfers that leave production decisions largely to farmers, while dedicated coupled actions target ruminant sectors explicitly. Equally important for policy makers are actions I 5.1 and I 5.2 (rows 3 and 4 in Equations (9) and (10))—coupled support for cows and young cattle dedicated to those sectors. Their impact is quite substantial (from 24%), arguably increasing the resilience and stability of this key income-generating sector. This also matters for crop production resilience via soil fertility maintenance—hence for sustainable development. For total livestock production (rightmost column), almost all intervention accrues to these four actions: two income supports and two dedicated to cows and cattle. Changes in this pattern are shown in Equation (11). Equation (11) reports .

Changes In The share of specific intervention actions in the total value of interventions planned for a given sector (in %) in years 2024–2028:

The results in Equation (11) may indicate a decline in the importance of income support and stabilization of dedicated interventions. Generally, this implies an expanding role for market mechanisms at the expense of sector-specific support. One may expect this to foster tendencies toward improving production efficiency (and its sources: structural change, innovation, technological progress).

Equations (9)–(14) are the empirical counterparts of the generic incidence matrix A introduced in

Section 3: Equations (9)–(11) correspond to column-normalized versions of A (shares of actions within sectors), while Equations (12)–(14) (

Section 4.3) correspond to row-normalized versions of matrix A (sector shares within actions).

4.3. Empirical Estimates of the Sector’s Share in Intervention Actions and Assessment

The next stage of inference draws on the empirical values in Equations (12) and (13) (obtained by row-wise division from Equations (6) and (7)) regarding a sector’s share in intervention actions, thus Equations (12)–(14) are row-normalized counterparts of Matrix A/X, reporting sector shares within each action. The Matrix C is defined as the row-normalized version of , where , capturing sector shares within each action. These figures can contribute to ranking or identifying sectoral priorities in agricultural policy embedded in the CSP. Equations (12) and (13) show sectoral shares in the value of support under each sectoral intervention action. Expressed as percentages, they allow an objective estimate of each sector’s share in the use of funds from a given action. This also reflects ranking—of sectors within actions. The analysis is row-wise (horizontal), as in CSP descriptions. The highest rank in absorbing the analyzed interventions (both general income and dedicated) goes to the milk sector (column 1), then beef (column 3). Together these two absorb over 60% of intervention funds. The other sectors, pigs (column 2) and poultry (column 4), obtain less and in almost equal proportions. A high share (about 40% to 90%) of the milk sector in absorbing funds across all actions—both dedicated (vertical) and horizontal income supports (the first two actions)—is notable. This can be positively assessed: the sector most crucial for the profitability, resilience, and stability of agricultural production is supported. Exiting and restoring production is most complex—and often impossible—in this sector. Milk is also most organically linked with production across all sectors (not only those analyzed). Its share in dedicated funds is, unsurprisingly, the largest—up to 90%. The second sector in the ranking is beef, absorbing from 10% to over 22% of horizontal and dedicated actions. Beyond the numbers, this allocation appears logical, given milk’s importance for agriculture and consumers, resilience to climate–environment conditions, sensitivity to market conditions, and overall robustness.

The sector’s share in support from a specific intervention action (in %) in the year 2024:

The sector’s share in support from a specific intervention action (in %) in year 2028:

Equation (14) compiles changes in sectoral shares within intervention support. The general conclusion is a stabilization of the sectoral structure, with slight shifts in favor of milk and clearer gains for poultry and beef, and a decline for pigs. This direction appears logical given the earlier reasoning.

Changes In The sector’s share in support from a specific intervention action (in %) in the years 2024–2028:

Summarizing this part of the analysis from Equations (9), (10), (12) and (13)—which map linkages, impacts, and rankings of actions and sectors in the CSP—we see that the two income-support actions are fundamental, and the largest beneficiaries are milk and pigs. The conclusions from Equations (9) and (10) pertain to sectoral priorities; those from Equations (12) and (13) pertain to action priorities. Together, they can underpin an assessment of the logic of the designed actions—assessed here as positive.

4.4. Empirical Estimates of Intervention Impacts on Sectors and Assessment

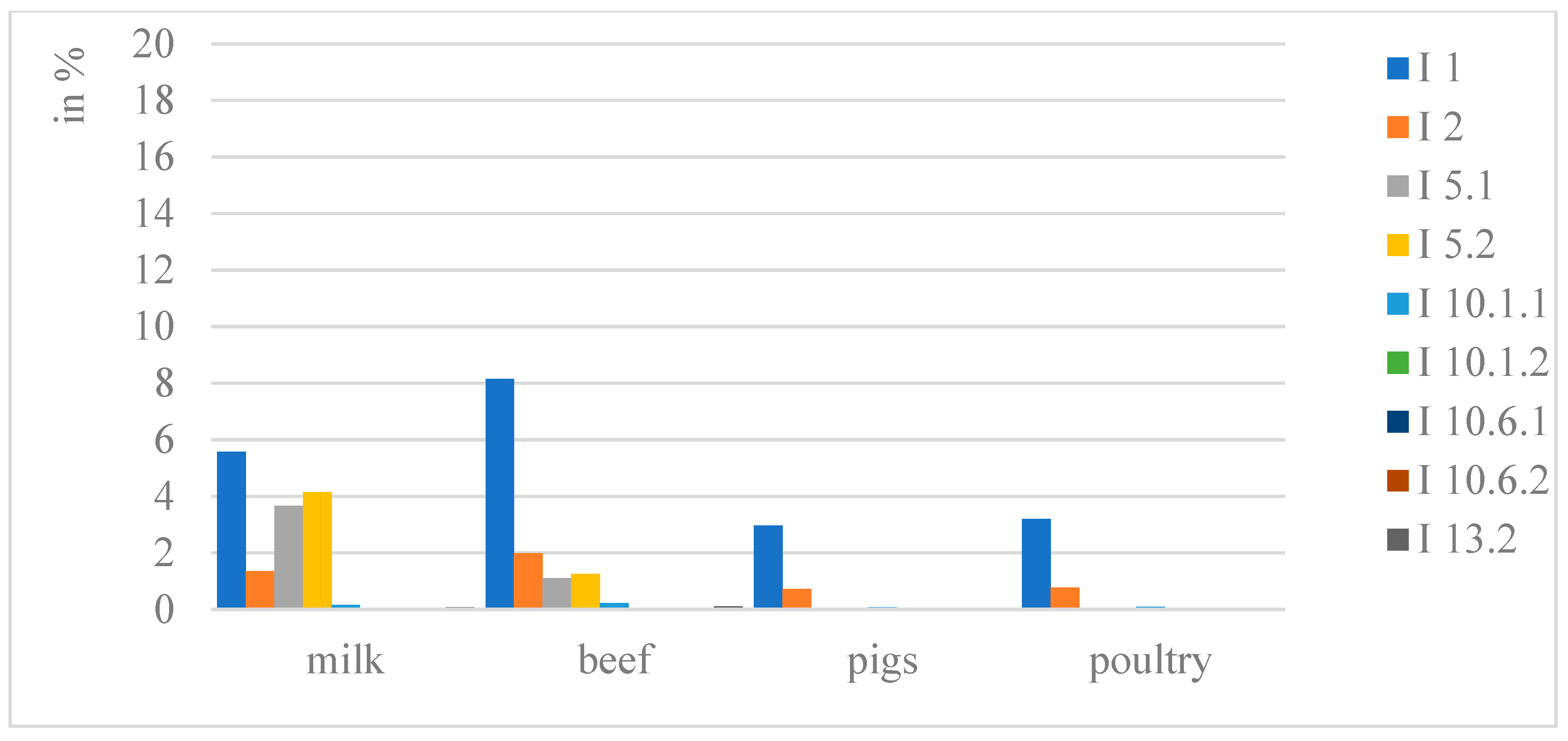

To assess the impact of the intervention actions on the agricultural markets (sectors) considered, one can relate the value of transfers from these actions to the value of final output in a given sector. A final output is a good proxy for assessing income effects. In essence, it determines sectoral revenues—the principal basis (reference point) for income—alongside already-incurred outlays, which tend to change more slowly over time than revenues; it is therefore an outcome category and necessarily a rough approximation. This narrows the impact assessment to the revenue base of producers in that sector. The value of final output is, to a very good approximation, the sector’s revenue; given costs, it is the immediate functional basis of income. This aligns with the study’s aim. The recalculated results are, as in previous matrices, expressed in relative terms (percentages) and presented in Equations (15) and (16), obtained by column-wise division. Analysis of Equations (15) and (16) can proceed by rows (horizontal) and by columns (vertical). Row-wise—this shows the effect of each action across sectors (i.e., the relative share of each sector within that action) and for livestock output as a whole. Column-wise—this shows the effect of each action and their sum on a given sector (the cumulative effect on that sector). The rightmost column captures support (from the actions included) as a share of total final livestock production. The general conclusion is that the relative impact of these interventions on sectoral final output and on the livestock aggregate is essentially negligible. Only for income-support actions (row 1) is this conclusion not fully warranted: the effect ranges from about 3.12% in poultry to 9.26% in beef. A more detailed analysis supports more nuanced inferences.

The share of the value of intervention activities in the value of commodity production sectors in year 2024 (in %):

The share of the value of intervention activities in the value of commodity production sectors in year 2028 (in %):

Row-wise analysis of Equations (15) and (16) confirms that the effect of each intervention’s support value on sectors ranges from negligible to sufficient—between a fraction of a percent (0.01) and just over 9%. The largest (still modest) impact is from Instrument I 1 (Basic income support) on beef and milk—about 6% and 9%, respectively. A similar effect—unsurprisingly, validating the method—appears for Instrument I 5.1 (Coupled support for cows), between 1.2% and 4.0% for beef and milk, respectively. Instrument I 5.2 (Coupled support for young cattle) is slightly higher (1.4–4.5%). This can be considered sufficient and unlikely to distort market regulation. The effects of the other interventions are negligible or nil when considered separately, for both direct and indirect impacts; this includes Instrument I 2 (Redistributive income support). The picture differs slightly for aggregate final livestock production (rightmost column): the effect of I 1 exceeds 14% (at least sufficient), while I 2 contributes a modest 3.20–3.50%. The remaining actions are practically irrelevant for both the aggregate and individual sectors. This row-wise view also reveals sectoral absorption of action-specific support: funds flow relatively more to milk and beef, implying sufficient influence primarily in milk and, to a lesser extent, beef. Pigs and poultry participate only marginally, so their impacts are negligible. This distribution appears logical: it builds resilience and stability without dictating production choices while sufficiently supporting the most sensitive and hardest-to-rebuild sector—milk.

Column-wise analysis shows each action’s effect on a given sector’s final output and, more importantly, the cumulative effect across all actions (column sums). Of course, in this study, the reference is to the nine intervention actions included here; nevertheless, in any future research encompassing all actions and all sectors, this will reflect the aggregate impact of the actions set out in the CAP Strategic Plan (CSP) on a given sector. Income action I 1 has the strongest effect across all sectors—from just over 3% to over 9%—largest in milk (>9%) and beef (>6%), smallest in poultry (>3%). In essence, this is a horizontal policy measure; however, it exerts effects on individual sectors (a vertical perspective), which is the focus of the analysis here. For pigs, it is >4% and 3.5%. Instrument I 2’s effect is minimal—0.8% to 2.3%; about 1.6% for milk and 2.3% for pigs, around 1.0% for beef and poultry. Dedicated actions I 5.1 and I 5.2 register but remain low—around 4.5% for milk and 1.2–1.5% for beef. The remaining interventions’ effects are near zero (fractions of a percent). This does not mean they are irrelevant; rather, their effects are not visible in this quantitative lens—particularly for actions like I 10.6.1 (Value chain cooperation—grants) and I 13.2 (Producer organizations and groups).

Different conclusions emerge when assessing the cumulative impact by sector (column sums). The combined effect on a given sector’s final output reaches economically non-negligible magnitudes relative to sectoral final output. The total effect ranges from over 4% for individual sectors to over 20% for aggregate livestock. Thus, this influence should be recorded as modest to sufficient—depending on the metric. The total for milk is about 16.5% (sufficient), for beef about 14% (also sufficient), for pigs just over 5%, and for poultry about 4.2% (minor but not dismissible). This distribution is logical in view of sectoral resilience and stability across differing production morphologies. This vertical analysis also permits ranking of interventions within sectors: the only materially significant actions are I 1 and I 2.

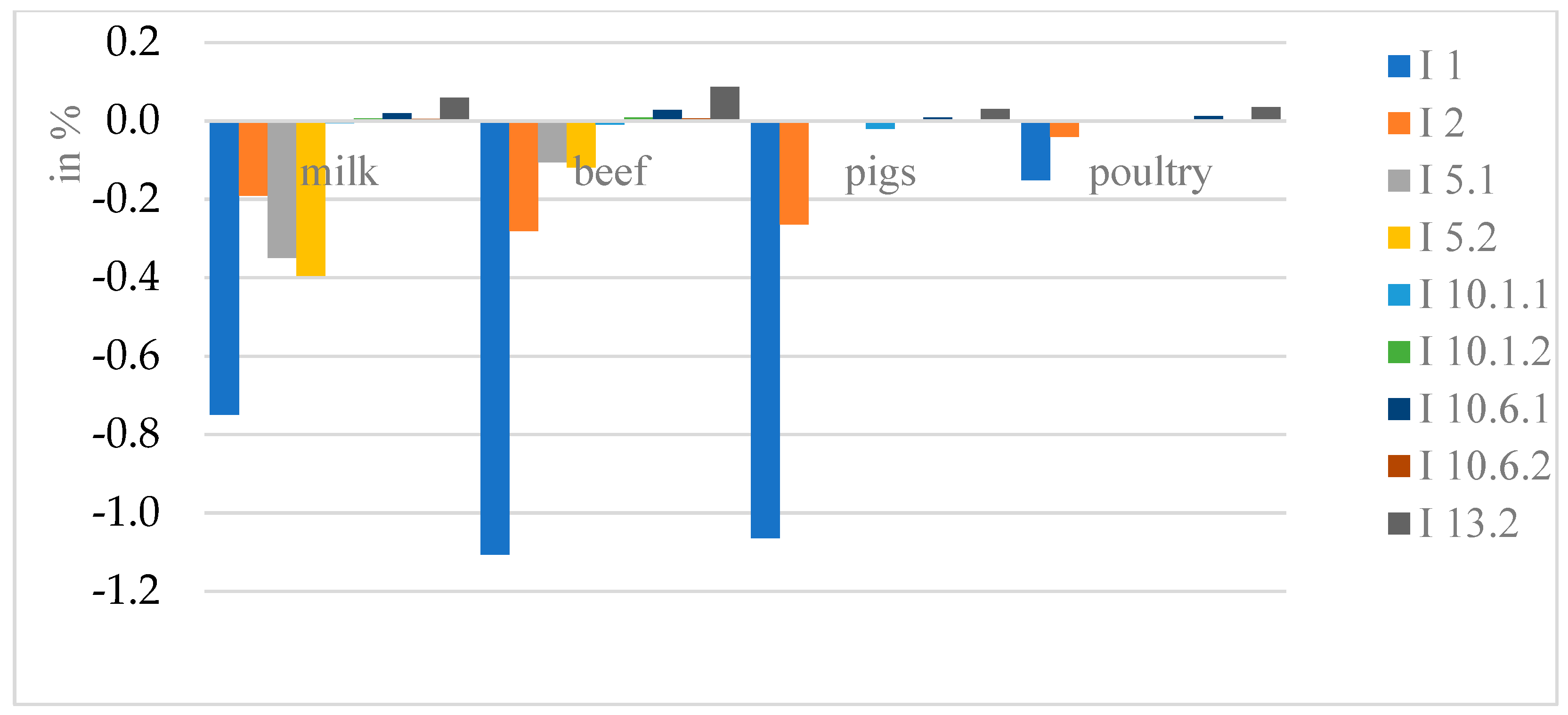

These impact coefficients changed only slightly over the period (Equation (17)), mainly decreasing for income support (rows 1 and 2) while remaining essentially unchanged for dedicated support. This can be read as leaving more room for market regulation mechanisms.

Changes In The share of the value of intervention activities in the value of commodity production sectors in the years 2024–2028 (in %):

We introduce a targeted robustness analysis that probes how sensitive the sector-level findings are to plausible uncertainty in the allocation keys of the two horizontal income supports—I 1 (Basic income support) and I 2 (Complementary redistributive support). These two actions dominate the mapping from policy to sectoral exposure; hence, verifying that our conclusions do not hinge on fine details of their sectoral split is essential. We consider ±10% perturbations to each sector’s share in both I 1 and I 2, one sector at a time, while keeping each action’s overall envelope fixed.

Table 2 reports the total relative influence by sector in 2024—defined as the column sum of the effect matrix expressed as a share of sectoral final output—together with the ranges generated when the respective sector’s shares in the two horizontal income supports (I 1 and I 2) are jointly tilted by ±10 percent around the baseline and the other sectors’ shares are renormalized within each action so that envelopes remain unchanged. The baseline magnitudes are 16.68 percent for milk, 14.43 percent for beef, 5.15 percent for pigs, and 4.29 percent for poultry. Under the reweighting exercise, the sectoral ordering is preserved and the level changes are moderate: milk varies between 15.88 and 17.48 percent, beef between 13.27 and 15.59 percent, pigs between 4.64 and 5.66 percent, and poultry between 3.87 and 4.71 percent. In absolute terms, the largest swing appears for beef at about 1.16 percentage points, followed by milk at 0.80 percentage points; pigs and poultry move by roughly one-half a percentage point. In proportional terms, the smaller sectors display larger percentage sensitivities to the same point change, but these do not overturn the baseline ranking or the substantive conclusions.

Table 3 extends the same robustness check to 2028. The baselines are lower than in 2024—15.07 percent for milk, 12.93 percent for beef, 3.84 percent for pigs, and 4.15 percent for poultry—consistent with a general softening of relative exposure. The ±10 percent tilts yield correspondingly smaller absolute swings for milk and pigs, with milk ranging from 14.35 to 15.79 percent and pigs from 3.46 to 4.22 percent. Beef remains the most responsive in level terms, spanning 11.89 to 13.97 percent (approximately 1.04 percentage points), while poultry ranges from 3.74 to 4.56 percent. Read together with the 2024 results, the exercise shows that reasonable reweighting of horizontal supports does not alter the sectoral hierarchy—milk and beef remain the most exposed sectors—nor does it materially change the interpretation that horizontal income measures dominate the mapping of policy support onto sectoral outcomes. Because the design of the robustness check is budget-neutral within each intervention row, it quantifies realistic within-envelope trade-offs: gains from tilting towards one sector are offset by small, proportionate reductions elsewhere, yet the overall pattern is stable.

4.5. Graphical Visualization of the Obtained Results

The above inferences from the empirical matrices can be transposed into a traditional graphical visualization (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This synthesizes the results and reasoning and thus needs no commentary.

5. Discussion

We do not claim that the proposed matrix framework is superior to established policy-analysis approaches (e.g., econometric evaluation, IO/SAM-based simulation, or CGE models). Each is suited to different evaluation tasks and data environments. The choice of an “optimal” method depends on the question at hand, identification requirements, and available data. Our contribution is a compact, transparent mapping from actions to sectors that complements those tools and can be used as a frontend diagnostic or as an input to richer models. In this application, the coverage is intentionally restricted to nine livestock-relevant actions and four sectors, chosen for their budgetary importance and data tractability; the framework itself is, however, directly scalable to the full CAP intervention portfolio.

In this application, the matrices serve as illustrations of possible use. Coverage is limited (actions, sectors, time) and uncertainty is treated parsimoniously (a budget-neutral ± 10%). Richer uncertainty treatments—for example, stochastic allocation keys, alternative envelope scenarios, and price–yield shocks explored via bootstrap or Monte Carlo simulations—could generate probabilistic ranges for sectoral exposure while preserving the framework’s interpretability.

A further limitation is that all coefficients are expressed in terms of gross transfers; participation and compliance (transaction) costs borne by farmers to access CAP support are not accounted for, so the matrix captures gross rather than net benefits of individual instruments. Incorporating such costs would allow closer welfare and net-benefit comparisons across measures and is a natural extension for future work.

Economically, the estimated exposure differences follow directly from CAP instrument logic and sector structure. Horizontal income supports (I 1–I 2) are proportional to eligible area and therefore scale with the land base and revenue profile of sectors; ruminant systems in Poland (milk and beef) are typically more land-intensive and more dependent on CAP transfers relative to market income, which raises their support-to-output ratios. Coupled payments to dairy cows and young cattle (I 5.1–I 5.2) further amplify this asymmetry by targeting ruminants explicitly, adding sizable dedicated effects in milk and beef and smaller spillovers across livestock markets. In contrast, pigs and poultry are more feed- and capital-intensive, less land-anchored, and rely more on market returns, so the same nominal envelopes translate into lower normalized incidence.

Our compact incidence map is intended as a transparent diagnostic complement to richer evaluation tools. Because CSP programming documents provide limited guidance on operational impact metrics, the framework offers a clear decomposition into dedicated (direct) and spillover (indirect) exposure and a comparable “support intensity” scale across sectors and years. Extending the mapping to all CAP actions and integrating price–quantity feedback or stochastic uncertainty would be the natural next steps.

Our sectoral exposure ranking is broadly consistent with earlier CAP incidence evidence obtained using IO-based and econometric approaches. IO-policy applications typically show that transfer intensity and multiplier-relevant exposure are highest in grazing-livestock and dairy systems, reflecting both their reliance on area-based income support and the targeting of voluntary coupled schemes [

30,

46]. EU-wide income studies likewise find that direct payments constitute a particularly large share of income in beef/grazing sectors and a substantial share in dairy, exceeding that observed in most other agricultural activities, which aligns with our finding of the strongest relative incidence in beef and milk [

47]. Recent empirical work on direct payments also reports heterogeneous sectoral and structural effects across Member States, with stronger dependence in ruminant systems and weaker relative exposure in monogastric sectors, mirroring our lower incidence in pigs and poultry [

4,

7,

8]. The absolute magnitudes are not directly comparable across studies because our framework normalizes envelopes by sectoral final output and is ex-ante for a selected intervention set, whereas IO multiplier studies propagate economy-wide linkages and econometric analyses estimate realized outcomes. Nonetheless, the alignment in sector ordering suggests that the compact incidence map captures a robust pattern of CAP leverage across livestock markets. Thus, beyond confirming a known ruminant-heavy incidence pattern, our approach shows how much of that pattern is attributable to horizontal versus coupled envelopes, and quantifies spillovers in a way that is directly readable for CSP allocation debates.

Poland has an official input–output (IO) table that could support a richer, economy-wide propagation analysis of CAP support. This is a limitation of the current application. Our ex-ante setting requires intervention-level allocation keys and sector-specific CSP envelopes, which are not available at the micro-detail needed for a full IO multiplier simulation at this stage. We therefore employ a parsimonious IO-inspired incidence map to retain transparency and minimize data demands during programming. A natural extension is to nest the action-by-sector mapping within the Polish IO/SAM framework or a CGE model, so that the same incidence structure can be combined with economy-wide multiplier effects and price–quantity feedbacks.

6. Summary and Conclusions

General methodological (instrumental) and substantive conclusions on the effects of intervention actions on selected sectors can be drawn. This study demonstrates the usefulness of a matrix-based approach for ex-ante (and ex-post) analyses and assessments of how agricultural policy affects farm management. The proposed matrix framework offers substantial analytical forecasting capacity for mapping linkages and effects of agricultural policy—especially interventions. It allows flexible delineation of policy actions and sectors or producer groups. One can test internal consistency with budget constraints, readily incorporate the organic nature of agricultural production, and anticipate the consequences of specific actions and linkages. A dynamic version, with row- and column-wise differences, further expands simulation and forecasting capabilities. The approach shown is illustrative of how this tool can be used in research and practice and appears accessible to policymakers. The present study is preliminary and paves the way for more extensive analysis.

Substantively, the analysis yields the following general conclusions. First, horizontal income interventions matter most in the sectors examined. In particular, Instrument I 1 (Basic income support) affects sectors in the range of about 5% to 14% individually, with an overall effect on final livestock output of about 14%. Second, while the effect of each action taken separately is at most sufficient or negligible, their cumulative effect by sector is meaningful. Third, there is a logical structure in the map of intervention impacts and agricultural markets (sectors): the most support goes to sectors both sensitive to changes in economic production conditions and important to the ecological system of agricultural production, where a return to production is more challenging and where support for resilience and stability is particularly needed. We do not contrast these findings with others, as the literature lacks studies in this specific formulation.

Future research could extend the analysis to all intervention actions, all sectors, and all CSP years to obtain a complete picture of linkages and support. A dynamic component could also be incorporated to illustrate how changes in support affect sectors in an ex-ante framework. The sectoral incidence coefficients developed here can also serve as transparent inputs or calibration targets for farm-level microsimulation or panel econometric models, enabling analysis of profitability, investment, and behavioral responses for different farm types and production systems. The same matrix structure is also readily extendable to environmental outcomes by appending columns for indicators such as fertilizer use, greenhouse gas emissions, or biodiversity proxies, thus allowing a parallel incidence map for environmental impacts alongside production effects.