Image Segmentation of Cottony Mass Produced by Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Olive Trees Using Deep Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A first well-annotated benchmark dataset was used for the segmentation of cottony masses produced by E. olivina in olive trees.

- Fine-tuning of ten state-of-the-art (SOTA) COD techniques was applied for the segmentation of cottony masses by E. olivina.

- A quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the results was obtained and discussed with these ten SOTA COD techniques for the segmentation of cottony mass produced by E. olivina.

2. Proposed Methodology

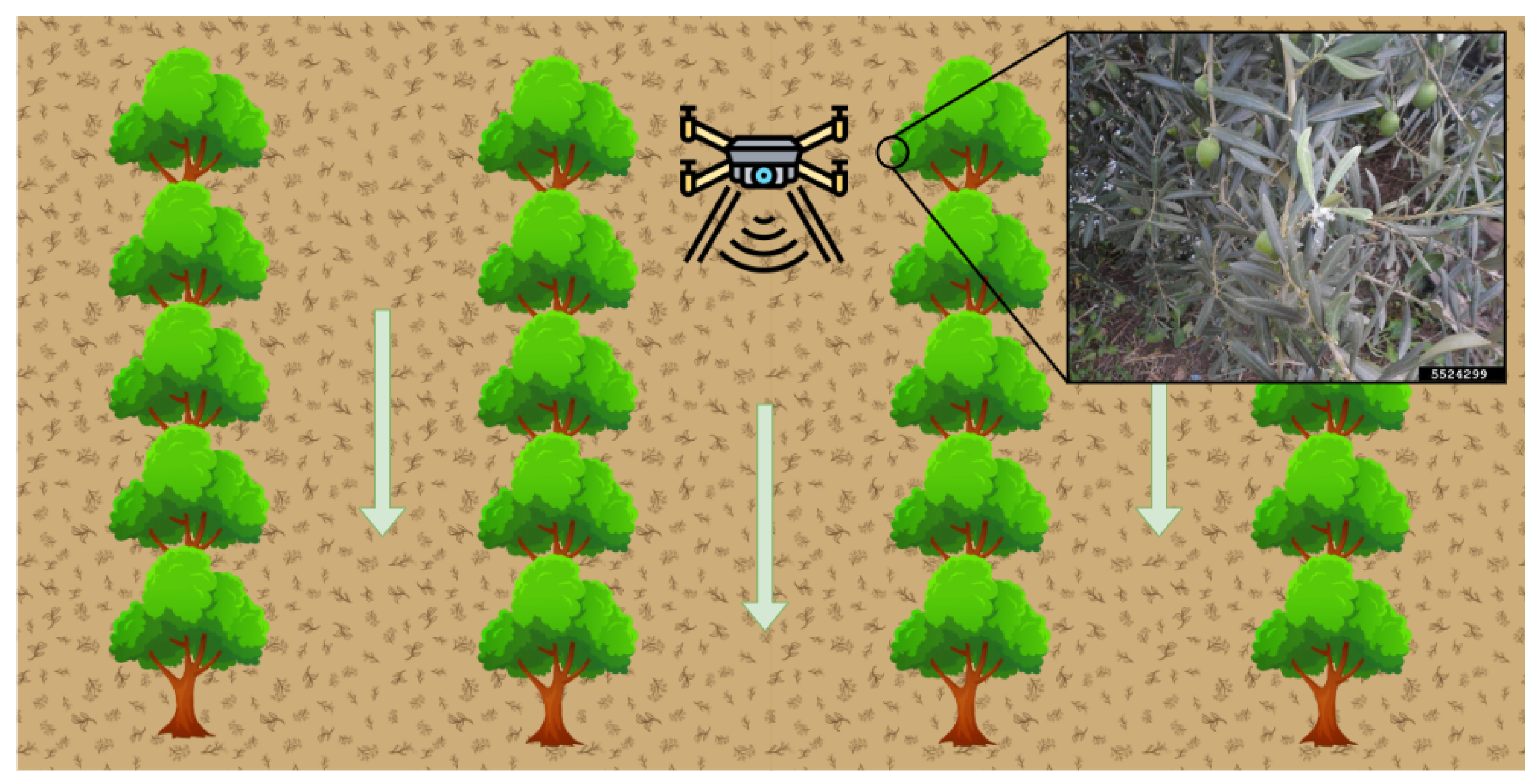

- Dataset Acquisition. A set of images containing cottony masses was collected from different sources.

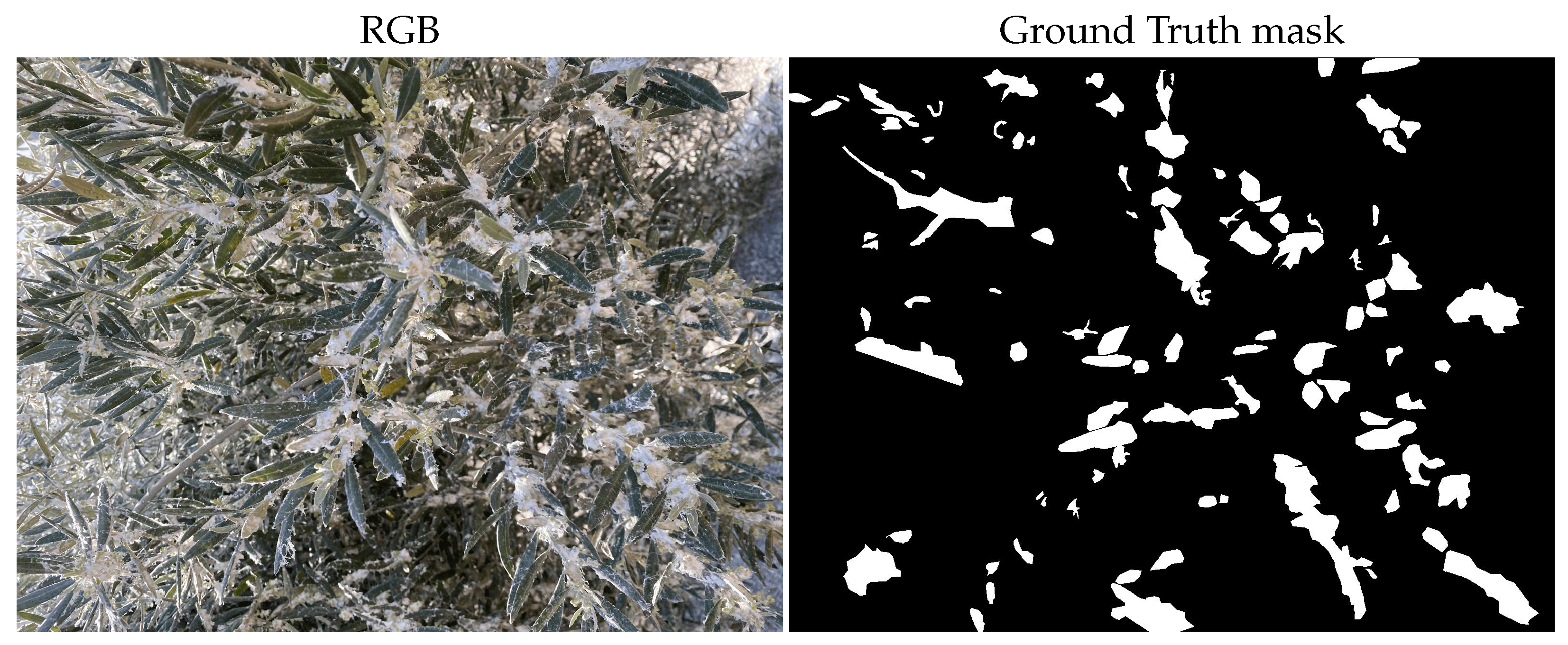

- Image Annotation. The collected images were annotated following strict guidelines to determine areas of cottony masses.

- Training COD Techniques. COD techniques were applied using the annotated dataset for training image-segmentation models.

- Testing COD Techniques. The trained models were evaluated on a test set to generate segmentation masks that identify the cottony masses.

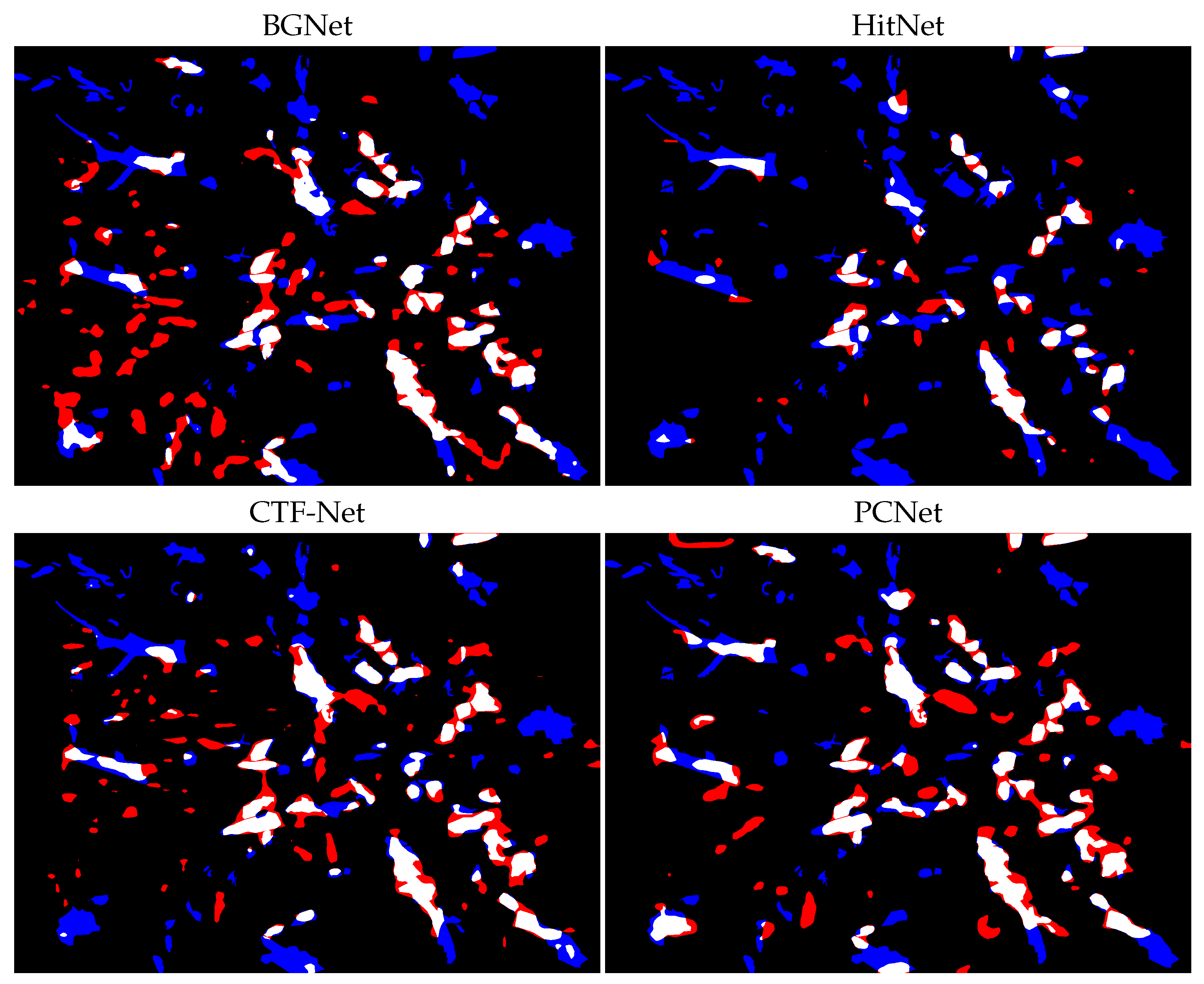

- Evaluation. Performance was assessed using both quantitative metrics and qualitative visual comparisons.

- Result Interpretation. The segmentation outputs were analyzed to determine the effectiveness of each COD technique in detecting and quantifying the cottony masses under challenging visual conditions.

2.1. Dataset Acquisition

2.2. Image Annotation

- Flip: Horizontal, Vertical

- 90° Rotate: Clockwise, Counter-Clockwise, Upside Down

- Rotation: Between −15° and +15°

- Shear: ±10° Horizontal, ±10° Vertical

2.3. Training COD Techniques

2.4. Testing COD Techniques

2.5. Evaluation

2.6. Training Details

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Aalaoui, M.; Sbaghi, M.; Mokrini, F. Effect of temperature on the development and reproduction of olive psyllid Euphyllura olivina Costa (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Crop Prot. 2025, 190, 107131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksantini, M.; Jardak, T.; Bouain, A. Temperature effect on the biology of Euphyllura olivina Costa. In Proceedings of the IV International Symposium on Olive Growing 586, Valenzano, Italy, 30 October 2002; pp. 827–829. [Google Scholar]

- Guise, I.; Silva, B.; Mestre, F.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Duarte, M.F.; Herrera, J.M. Climate change is expected to severely impact Protected Designation of Origin olive growing regions over the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. Syst. 2024, 220, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, T. Factors affecting the distribution of Euphyllura olivina Costa (Hom., Psyllidae) on olive. Z. Angew. Entomol. 1984, 97, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougardy, E.; Wang, X.; Hogg, B.N.; Johnson, M.W.; Daane, K.M.; Pickett, C.H. Current distribution of the olive psyllid, Euphyllura olivina, in California and initial evaluation of the Mediterranean parasitoid Psyllaephagus euphyllurae as a biological control candidate. Insects 2020, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guessab, A.; Elouissi, M.; Lazreg, F.; Elouissi, A. Population dynamics, seasonal fluctuations and spatial distribution of the olive psyllid Euphyllura olivina Costa (Homoptera, Psyllidae) in Algeria. Arx. Misc. Zool. 2021, 19, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Marouf, A.; Shafiei, S.E.; Abdollahi, A. The effects of phenolic compounds on the abundance of olive psyllid, Euphyllura straminea Loginova in commercial and promising olive cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharbi, N. Effectiveness of inundative releases of Anthocoris nemoralis (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) in controlling the olive psyllid Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2021, 118, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco Navero, D.; Fernandez Escobar, R.; Rallo Romero, L. El Cultivo del Olivo, 7th ed.; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Onufrieva, K.S.; Onufriev, A.V. How to count bugs: A method to estimate the most probable absolute population density and its statistical bounds from a single trap catch. Insects 2021, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ferrer, M.T.; Ripollés, J.L.; Garcia-Marí, F. Enumerative and binomial sampling plans for citrus mealybug (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae) in citrus groves. J. Econ. Entomol. 2006, 99, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, A.; Ren, C.; Wu, J. A survey on deep learning-based camouflaged object detection. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Gao, C.; Dehghan, M.; Jagersand, M. BASNet: Boundary-Aware Salient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.P.; Ji, G.P.; Cheng, M.M.; Shao, L. Concealed object detection. Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 6024–6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Jiang, S.; Qi, L. Edge-aware mirror network for camouflaged object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Brisbane, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2465–2470. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Qin, X.; Dai, H.; Ren, W.; Luo, D.; Tai, Y.; Shao, L. High-resolution iterative feedback network for camouflaged object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 881–889. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, Q.; Li, Z. An effective CNN and Transformer fusion network for camouflaged object detection. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2025, 259, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xiao, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, S. Boundary-guided network for camouflaged object detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 248, 108901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Liu, S.J.; Sun, Y.J.; Ji, G.P.; Wu, Y.F.; Zhou, T. Camouflaged object detection via context-aware cross-level fusion. Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6981–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.P.; Fan, D.P.; Chou, Y.C.; Dai, D.; Liniger, A.; Van Gool, L. Deep gradient learning for efficient camouflaged object detection. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Chen, P.; Leonardis, A.; Fan, D.P. PlantCamo: Plant Camouflage Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Barnes, N. Modeling aleatoric uncertainty for camouflaged object detection. In Proceedings of the Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 1445–1454. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.H.; Cheng, M.M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Torr, P. Res2net: A new multi-scale backbone architecture. Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 43, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pvt v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.P.; Cheng, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Borji, A. Structure-measure: A new way to evaluate foreground maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4548–4557. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, R.; Zelnik-Manor, L.; Tal, A. How to evaluate foreground maps? In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Perazzi, F.; Krähenbühl, P.; Pritch, Y.; Hornung, A. Saliency filters: Contrast based filtering for salient region detection. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.P.; Gong, C.; Cao, Y.; Ren, B.; Cheng, M.M.; Borji, A. Enhanced-alignment measure for binary foreground map evaluation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.10421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achanta, R.; Hemami, S.; Estrada, F.; Susstrunk, S. Frequency-tuned salient region detection. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1597–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.J.R. Guía de manejo integrado del algodoncillo,“ Euphyllura olivina”. Phytoma España Rev. Prof. Sanid. Veg. 2022, 343, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

| Technique | Source | Year | Source Type | Image Size (px) | Backbone | #Par. (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASNet [15] | CVPR | 2019 | Conference | ResNet-34 [25] | 87.06 | |

| SINet-v2 [16] | TPAMI | 2021 | Journal | Res2Net-50 [26] | 24.93 | |

| BGNet [20] | IJCAI | 2022 | Conference | Res2Net-50 [26] | 77.80 | |

| C2F-Net [21] | TCSVT | 2022 | Conference | Res2Net-50 [26] | 26.36 | |

| OCENet [24] | WACV | 2022 | Conference | ResNet-50 [25] | 58.17 | |

| EAMNet [17] | ICME | 2023 | Conference | Res2Net-50 [26] | 30.51 | |

| DGNet [22] | MIR | 2023 | Journal | EfficientNet [27] | 8.30 | |

| HitNet [18] | AAAI | 2023 | Conference | PVTv2 [28] | 25.73 | |

| PCNet [23] | arXiv | 2024 | - | PVTv2 [28] | 27.66 | |

| CTF-Net [19] | CVIU | 2025 | Journal | PVTv2 [28] | 64.48 |

| Technique | Optimizer | LR | BS | Epochs | Scheduler | Loss Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASNet [15] | Adam | 1 × | 8 | 1000 | ReduceLROnPlateau | BCE + SSIM + IOU (multi-stage fusion) |

| SINet-v2 [16] | Adam | 1 × | 16 | 150 | Custom (Adjust LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) |

| BGNet [20] | Adam | 1 × | 12 | 100 | Custom (Poly LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) + Dice loss (edge) |

| C2F-Net [21] | AdaXW | 1 × | 32 | 50 | Custom (Poly LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) |

| OCENet [24] | Adam | 1 × | 4 | 50 | StepLR | Uncertainty aware structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) |

| EAMNet [17] | AdamW | 5 × | 16 | 150 | Custom (Adjust LR) | Hybrid loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) + Edge loss (edge) |

| DGNet [22] | AdamW | 5 × | 16 | 150 | CosineAnnealingLR | Hybrid loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) + MSE loss (grad) |

| HitNet [18] | AdamW | 1 × | 8 | 150 | Custom (Adjust LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) |

| PCNet [23] | AdamW | 1 × | 8 | 150 | Custom (Adjust LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) |

| CTF-Net [19] | Adam | 1 × | 12 | 100 | Custom (Poly LR) | Structure loss (weighted BCE + weighted IOU) + Dice loss (edge) |

| Technique | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASNet [15] | 0.7556 | 0.5634 | 0.0329 | 0.8144 | 0.8364 | 0.8555 | 0.5744 | 0.6095 | 0.6395 |

| SINet-v2 [16] | 0.7778 | 0.6038 | 0.0285 | 0.8343 | 0.8826 | 0.9160 | 0.5809 | 0.6456 | 0.6873 |

| BGNet [20] | 0.8022 | 0.5978 | 0.0278 | 0.8951 | 0.9054 | 0.9262 | 0.6816 | 0.7190 | 0.7528 |

| C2F-Net [21] | 0.7708 | 0.5248 | 0.0342 | 0.8282 | 0.8807 | 0.9220 | 0.5780 | 0.6386 | 0.6937 |

| OCENet [24] | 0.7854 | 0.6558 | 0.0251 | 0.9099 | 0.8982 | 0.9178 | 0.6726 | 0.7054 | 0.7277 |

| EAMNet [17] | 0.7435 | 0.4125 | 0.0477 | 0.8821 | 0.8839 | 0.9195 | 0.6498 | 0.6738 | 0.7340 |

| DGNet [22] | 0.7833 | 0.6060 | 0.0278 | 0.8362 | 0.8873 | 0.9144 | 0.5833 | 0.6510 | 0.6877 |

| HitNet [18] | 0.7929 | 0.6735 | 0.0220 | 0.9125 | 0.9155 | 0.9195 | 0.6911 | 0.7046 | 0.7206 |

| PCNet [23] | 0.8075 | 0.6787 | 0.0234 | 0.9016 | 0.9144 | 0.9232 | 0.6840 | 0.7101 | 0.7394 |

| CTF-Net [19] | 0.8101 | 0.6224 | 0.0314 | 0.8859 | 0.9013 | 0.9280 | 0.6656 | 0.7041 | 0.7493 |

| Technique | Dice | IoU | IoU@50 | IoU@75 | IoU@[0.50:0.95] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASNet [15] | 0.629 | 0.500 | 0.396 | 0.145 | 0.167 |

| SINet-V2 [16] | 0.670 | 0.547 | 0.459 | 0.208 | 0.217 |

| BGNet [20] | 0.732 | 0.616 | 0.522 | 0.278 | 0.297 |

| C2F-Net [21] | 0.677 | 0.547 | 0.421 | 0.151 | 0.205 |

| OCENet [24] | 0.695 | 0.568 | 0.505 | 0.180 | 0.221 |

| EAMNet [17] | 0.708 | 0.587 | 0.484 | 0.244 | 0.256 |

| DGNet [22] | 0.675 | 0.544 | 0.443 | 0.151 | 0.194 |

| Hitnet [18] | 0.704 | 0.583 | 0.514 | 0.267 | 0.245 |

| PCNet [23] | 0.718 | 0.599 | 0.508 | 0.272 | 0.268 |

| CTF-Net [19] | 0.735 | 0.621 | 0.562 | 0.279 | 0.302 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velesaca, H.O.; Ruano, F.; Gomez-Cantos, A.; Holgado-Terriza, J.A. Image Segmentation of Cottony Mass Produced by Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Olive Trees Using Deep Learning. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232485

Velesaca HO, Ruano F, Gomez-Cantos A, Holgado-Terriza JA. Image Segmentation of Cottony Mass Produced by Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Olive Trees Using Deep Learning. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232485

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelesaca, Henry O., Francisca Ruano, Alice Gomez-Cantos, and Juan A. Holgado-Terriza. 2025. "Image Segmentation of Cottony Mass Produced by Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Olive Trees Using Deep Learning" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232485

APA StyleVelesaca, H. O., Ruano, F., Gomez-Cantos, A., & Holgado-Terriza, J. A. (2025). Image Segmentation of Cottony Mass Produced by Euphyllura olivina (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in Olive Trees Using Deep Learning. Agriculture, 15(23), 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232485